Abstract

Repetitive motor behaviors are common in neurodevelopmental, psychiatric, and neurological disorders. Despite their prevalence in certain clinical populations, our understanding of the neurobiological cause of repetitive behavior is lacking. Likewise, not knowing the pathophysiology has precluded efforts to find effective drug treatments. Our comparisons between mouse strains that differ in their expression of repetitive behavior revealed an important role of the subthalamic nucleus. In mice with high rates of repetitive behavior, we found significant differences in dendritic spine density, gene expression, and neuronal activation in the subthalamic nucleus. Taken together, these data demonstrate a hypoglutamatergic state. Furthermore, by using environmental enrichment to reduce repetitive behavior, we found evidence of increased glutamatergic tone in the subthalamic nucleus with our measures of spine density and gene expression. These results suggest the subthalamic nucleus is a major contributor to repetitive behavior expression and highlight the potential of drugs that increase subthalamic nucleus function to reduce repetitive behavior in clinical populations.

Keywords: repetitive behavior, C58 mice, environmental enrichment, basal ganglia, subthalamic nucleus

INTRODUCTION

Restricted, repetitive behavior refers to a broad class of actions that are typified by repetition of response elements, rigidity or inflexibility, and lack of apparent purpose (Lewis & Kim, 2009). This class of responses includes repetitive sensory-motor behaviors (e.g., stereotyped movements, compulsions) and behaviors that reflect an insistence on sameness or resistance to change (e.g., rituals, restricted interests) (Bodfish et al., 2000; Lewis & Bodfish, 1998). Restricted, repetitive behavior is diagnostic for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and a very common feature of a number of other neurodevelopmental disorders including syndromic (e.g., Rett, Fragile X, Prader-Willi syndromes) and non-syndromic intellectual and developmental disability (Cipriani et al., 2013; Leekam et al., 2011; Lewis & Bodfish, 1998; Moss et al., 2009; Prioni et al., 2012). Additionally, repetitive behavior is a feature of the clinical presentation of other disorders that manifest across the life-span including obsessive-compulsive disorder, Tourette syndrome, schizophrenia, and fronto-temporal and Alzheimer’s dementia (Cath et al., 2001; Nyatsanza et al., 2003; Singer, 2013). Other conditions including congenital blindness and early social impoverishment are also associated with aberrant repetitive behavior (Fazzi et al., 1999; Fisher et al., 1997; Rutter et al., 1999).

Limited information is available from clinical studies about the neurobiological mechanisms that mediate repetitive behavior in neurodevelopmental disorders (Whitehouse & Lewis, 2015). Reliable biomarkers have not been found and only a small number of causative genes have been advanced for ASD. Neuroimaging studies have implicated cortical-basal ganglia circuitry (see Traynor & Hall, 2015 for a review) but specific pathways and mechanisms within such circuitry remain elusive. Animal models provide the opportunity to identify neurobiological mechanisms that mediate the expression of abnormal repetitive behavior.

A number of animal models have been employed to investigate the inducing conditions, neurobiology and potential treatments of repetitive behavior characteristic of neurodevelopmental disorders (see Bechard & Lewis, 2012 for a review). We (Muehlmann et al., 2012) and others (Moy et al., 2008; Ryan et al., 2010) have demonstrated that the C58 inbred mouse strain (Mus musculus) exhibits a robust repetitive behavior phenotype expressed as high levels of spontaneous stereotypic hind limb jumping and backward somersaulting (Supporting Information video S1). These behaviors are expressed at or before weaning, persist throughout development, and are readily observed throughout the dark cycle in both the home cage and individual test cages (Ryan et al., 2010; Muehlmann et al., 2012). Moreover, we have shown that C58 mice exhibit a pronounced resistance to change or behavioral inflexibility in a reversal learning task (Whitehouse et al., 2017). We have also shown that rearing C58 mice in environmental enrichment for six weeks starting at weaning (postnatal day 21) dramatically reduced repetitive motor behaviors compared to littermates reared in standard cages (Muehlmann et al., 2012) and improved reversal learning (Whitehouse et al., 2017).

Excessive self-grooming behavior is a common repetitive behavior in mouse models of psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders (Kalueff et al., 2016). Self-grooming in rodents is sequentially fixed and highly stereotyped. C58 mice show increased duration and a higher number of grooming bouts at some developmental time points and during some social and non-social testing conditions (Ryan et al., 2010). A complete sequential syntactic self-grooming analysis has not been completed in C58 mice and there is little evidence that their grooming behavior could be described as excessive (i.e. they do not show tissue trauma because of increased grooming). We view the C58 mouse model as a complement to the excessive grooming models, which together hold high translational value for the study of human disorders that involve highly fixed action patterns.

The repetitive behavior phenotype of C58 mice is strikingly similar to that of deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus) which also exhibit high levels of spontaneous vertical jumping and backward somersaulting (Hadley et al., 2006; Powell et al., 2000; Presti & Lewis, 2005; Turner et al., 2002; 2003; Turner & Lewis, 2003). Our previous studies with deer mice implicated reduced indirect basal ganglia pathway activity as a mediator of the expression of high levels of repetitive behavior. For example, we demonstrated that neuronal metabolic activity in the subthalamic nucleus (STN), a key indirect basal ganglia pathway brain region, was significantly lower in high repetitive behavior deer mice compared to low repetitive behavior deer mice and significantly negatively correlated with the total amount of repetitive behavior exhibited (Tanimura et al., 2011). In addition, pharmacological activation of the indirect pathway resulted in a significant, selective, and dose-dependent reduction of repetitive behavior (Tanimura et al., 2010). We have also demonstrated that environmental enrichment attenuation of repetitive motor behavior in deer mice (Bechard et al., 2017) was associated with significant increases in neuronal activation and dendritic spine densities only in the STN and globus pallidus, both of which are key indirect basal ganglia pathway nuclei in mice (Bechard et al., 2016).

In the present study, we sought to determine if decreased indirect basal ganglia pathway activation also mediated repetitive behavior in the C58 inbred mouse model. In order to test this overall hypothesis, we compared C58 mice to C57BL/6 mice using a measure of neuronal metabolic capacity in multiple brain regions. We hypothesized that C58 mice would exhibit significantly less functional activation selectively in brain regions that make up the indirect basal ganglia pathway. In order to determine if such differences were attributable to repetitive behavior and not a reflection of generalized strain differences, we also examined neuronal metabolic activity in an F2 generation of mice that were the offspring of a C58 by C57BL/6 intercross. We hypothesized that F2 high repetitive behavior mice would exhibit significantly reduced neuronal activation in indirect basal ganglia pathway brain nuclei compared to F2 low repetitive behavior mice. Based on our neuronal metabolic activity findings, we further examined a key indirect basal ganglia pathway brain region, the STN, for strain differences in dendritic spine density and gene expression. We hypothesized that C58 mice would have significantly fewer dendritic spines in the STN compared to C57BL/6 mice and that their gene expression profile would indicate hyper GABAergic tone and less evidence of synaptic plasticity. Finally, we sought to determine if environmental enrichment-induced attenuation of repetitive behavior in C58 mice was associated with increased neuronal metabolic activity and dendritic spine density as well as altered gene expression in the STN.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study 1: Strain comparisons

Animals

C58 mice (n=21; four females, 17 males) and C57BL/6 mice (n=20; five females, 15 males) were bred and housed in our colony room at the University of Florida. Mice sharing the same weaning date were group-caged (4–6 mice/cage) at weaning (PND 21) in standard rodent cages (48 x 27 x 15 cm) and they remained in the same cage group throughout the experiment. Both the humidity (50%–70%) and temperature (70–75°F) were controlled, and the room was maintained on a 12,12 light, dark cycle (lights off at 8:00 pm). Animal care and use was performed in accordance with NIH Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Adequate measures were taken to minimize any pain or discomfort.

Assessment of Repetitive Behavior

Vertical hindlimb jumping and backward somersaulting, the primary repetitive motor behaviors in C58 mice, were quantified using photobeam arrays (Columbus Instruments). Vertical displacement resulted in photobeam interruptions that were recorded as repetitive behavior counts with accompanying time stamps (Muehlmann et al., 2012). The apparatus was set so rearing or other non-stereotyped vertical activity did not result in photobeam interruptions. All test sessions were video-recorded to identify the topography of repetitive behavior and verify the accuracy of the automated counters. All C58 and C57BL/6 mice were assessed for their repetitive motor behaviors at postnatal day 63 using the apparatus just described. Mice were placed in individual chambers (28 x 22 x 25 cm) 1 h before testing began. Following habituation, each animal was assessed for the entire 12 h dark cycle with food and water available.

Cytochrome Oxidase (CO) histochemistry

CO activity reflects the oxidative metabolic capacity of neurons due to its functional role in the process of generating ATP (Wong-Riley et al., 1998). CO activity is a relative measure of long-term (days to weeks) neuronal metabolic activity (Sakata et al. 2005), and has previously been used to detect differences in activation of basal ganglia nuclei as a function of repetitive motor behaviors (Bechard et al., 2016; Tanimura et al., 2010, Tanimura et al., 2011; Turner et al., 2002). The optical density dependent variable is a metric for the amount of light that passes through the tissue stained for CO. Thus, darker staining will have a higher optical density value indicating more CO activity (Wong-Riley, 1989). The CO staining protocol (Gonzalez-Lima & Cada, 1998) was performed on brains that were snap-frozen in 2-methylbutane and stored in a −80°C freezer. Sagittal sections (20 μm) sliced on a cryostat (−20°C) were collected from both hemispheres at 1–2 mm lateral to the midline and mounted onto microscope slides (Superfrost Plus, FisherBrand) with 6 sections on one slide. These adjacent sections were collected 100 μm apart. Standards were made from homogenized brain tissue of non-subject mice and were included in each assay to ensure linearity of optical density measurements. Slides were stained and then cover slipped with Permount.

Optical density measurements were taken (ImagePro software, Media Cybernetics) from the basal ganglia regions of interest, dorsal striatum, globus pallidus, STN, and substantia nigra (pars reticulata and pars compacta), as well as the hippocampus and motor cortex. The hippocampus was selected as an additional reference region. For each brain region, traces were drawn around each individual region (Supporting Information figure S1) and optical density values were calculated by averaging the optical density measurements across multiple adjacent sections.

Golgi-Cox staining

Golgi-Cox staining was used to assess dendritic morphology in the STN. Thirteen hours after (9 pm) behavioral testing, mice were anesthetized with isoflourane and sacrificed by decapitation. Golgi-Cox staining was completed according to FD Rapid GolgiStain Kit guidelines (FD NeuroTechnologies, Inc., Colombia, MD). In brief, brains were removed and placed into the first solution for Golgi-Cox staining (equal parts solution A and B). Time from sacrifice to immersion was less than one minute. Brains were impregnated in solution for 2 weeks at room temperature in a dark environment. Brains were then transferred to solution C for 72 hours at room temperature. After this time, the brains were sliced in a 30% sucrose solution into 200 μm coronal sections using a Vibratome, and allowed to dry at room temperature without exposure to light. The slides were then stained with solutions D and E, rinsed, dehydrated, cleared with CitriSolv (Fisher Scientific), and coverslipped with Permount.

Dendritic spine density was quantified using ImagePro (Media Cybernetics) and a Zeiss microscope with Leica DFC camera with a 40x air objective, a 2.5x camera tube objective, 1.5x on the magnification changer, and a built-in 1.25x magnifier in the scope (40x4.6875 total) by an observer blind to group. Within the STN (Supporting Information figure S2), spines along unobstructed dendritic segments >15 μm were marked on graphic overlays on live digital video images during continuous manual focus adjustment. Any protrusion from the main cylindrical column of the dendrite was counted as a spine. After labeling all the spines along a sample, the approximate dendritic cylinder centerline was traced for return of calibrated length by the software. Dendrites were measured starting beyond the first bifurcation point and at least 50 μm from the soma. Within each region of interest, 10–12 dendrites were measured ensuring samples represented both hemispheres and multiple tissue sections. Spine densities were calculated as the total number of spines divided by the total length of dendrite segments, such that each animal had one density measurement.

Gene expression assay

Thirteen hours (9 pm) after behavioral testing, mice used for gene expression analyses were subjected to cervical dislocation followed by rapid decapitation. Brains were quickly removed from the skull and frozen in cold 2-methylbutane. Whole brains were stored at −80C until they were transferred to a cryostat held at −10C and sliced at 300um. A 0.5mm tissue puncher was used to dissect STN from the coronal slices. RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Micro Kit and cDNA was synthesized using RT2 First Strand Kit. The cDNA from each STN sample was added to RT2 Sybr Green mastermix and loaded onto both the RT2 Profiler PCR GABA and glutamate array (cat. no. PAMM-126Z) and the synaptic plasticity array (cat. no. PAMM-152Z). These PCR arrays were run on an ABI 7500HT thermocycler. Each of these arrays contain primer sets for 84 genes and 5 housekeeping genes.

Study 2: F2 high and low repetitive motor behavior mice

To assess whether neurobiological differences between C58 and C57BL/6 mice were specific to repetitive behavior rather than non-selective strain differences, we generated F2 mice using the offspring of a F1 C58 X C57BL/6 intercross. A standard mating strategy using three female C57BL/6 and three male C58 mice was employed to generate the F1 mice (n=71). The F1 offspring were brother-sister mated to produce F2 pups (n=302). The F2 mice were housed 3–5 per cage in standard caging under a 12,12 hour light/dark cycle as in Study 1. We selected the 12 mice (6 male, 6 female) with the highest repetitive motor behavior scores and the 12 mice (6 male, 6 female) with the lowest repetitive motor behavior scores. From the population of 302 F2 mice, the repetitive behavior counts (averaged over two 12 hour dark cycles) ranged from 37 to 24,130. Tissue from these 24 mice were used in CO staining assays as described for Study 1.

Study 3: Effects of environmental enrichment

For the experiments comparing differences between standard housing and environmental enrichment, 21 C58 mice (7 females, 14 males) were randomly assigned to environmental enrichment (EE). Littermates of the EE C58 mice (n=20; two females, 18 males) were used for the standard housing control group and weaned and housed as described for Study 1. EE mice were weaned at postnatal day 21 and then housed in dog kennels (121.9 × 81.3 × 88.9 cm; housed with 4–6 other same-sex mice) customized with two extra levels and connected ramps constructed from galvanized wire (Muehlmann et al., 2012). A running wheel, a large opaque shelter, and Habitrail tubes were kept in each kennel throughout the six-week enrichment period. Various objects (e.g., plastic toys, domes) were also present in each kennel, but they were rotated weekly to maintain novelty. During the weekly rotation of objects, approximately 2 oz. of bird seed was scattered into the kennel to promote foraging. Water was available ad lib, and four Nestlet squares were provided for nest construction. Kennels were kept in the same room that housed standard cage animals.

Differences in repetitive motor behavior between enriched and standard housed C58 mice were assessed as described for Study 1. Neurobiological differences between these housing conditions were evaluated using CO histochemistry, Golgi-Cox staining, and gene expression assays as described for Study 1.

Statistical analysis

In study 1, repetitive behavior counts were analyzed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with main effect variables sex and strain. Bonferroni post-tests were performed for further comparisons within male and female groups. For cytochrome oxidase histochemistry, optical density measurements were analyzed by two-tailed t-tests for each brain region. For Golgi-Cox staining of dendritic spines, two-tailed t-tests were also performed. For the gene expression assays, data were analyzed using the GeneGlobe Data Analysis Center software (available from qiagen.com) which used the ΔΔCT method. Two housekeeping genes were used for normalization of the data. A significance level of 0.05 was used, employing the Benjamini-Hochburg procedure to control for multiple comparisons. This involved rank ordering the gene hits by p-value then dividing by the total number of comparisons (148 individual genes across the two arrays) and adjusting for a false discovery rate (FDR) of 20%. The FDR was selected based on the exploratory nature of the study.

In study 2, repetitive behavior counts were averaged over two test sessions. This was done in order to confirm appropriate assignments to the “low” and “high” repetitive behavior groups. The repetitive behavior count data and cytochrome oxidase histochemistry optical density data were each analyzed with two-way ANOVAs with main effects of sex and repetitive behavior group. In study 3, repetitive behavior counts, cytochrome oxidase histochemistry optical density measures for each brain region, and dendritic spine density data were each analyzed by two-tailed t-tests. The gene expression data were analyzed as described for study 1.

RESULTS

Study 1: Strain comparison

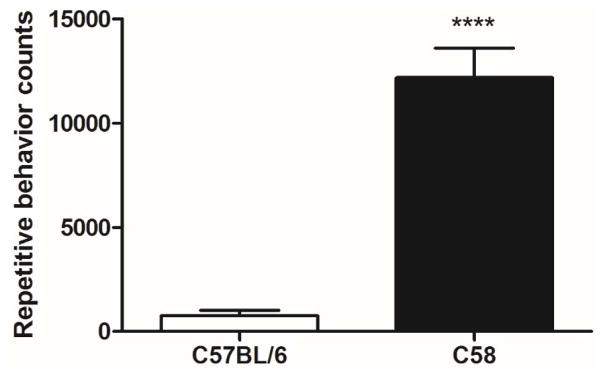

Strain differences in repetitive motor behavior replicated our previous finding that C58 mice show substantially more repetitive behavior than C57BL/6 mice (Muehlmann et al., 2012; Fig. 1). A two-way ANOVA showed a significant main effect of strain (F(1,37)=31.53, p<0.0001) and no significant main effect of sex (F(1,37)=0.13, p=0.72) or a strain x sex interaction (F(1,37)=1.74, p=0.2). Bonferroni post-tests confirmed significant group differences within both female and male comparisons (females, t=2.43, p<0.05, males, t=7.43, p<0.0001).

Figure 1.

Mouse strain comparison of repetitive behavior counts. C58 mice show significantly more repetitive behavior than C57BL/6 mice. Figure shows mean + SEM (**** p<0.0001 for strain main effect).

CO histochemistry

Comparisons of CO staining across discrete regions of the brain included 13 C58 mice (nine male, four female) and 11 C57BL/6 mice (five female, six male). For this smaller cohort, C58 mice showed significantly more repetitive behavior than C57BL/6 mice, as revealed by a two-tailed t-test (t(22)=4.47, p=0.0002). Table 1 shows the mean optical density values for each brain region for the two strains of mice. The only significant difference in CO staining was found in the STN where C58 mice had significantly lower values than C57BL/6 mice (t(22)=2.76, p=0.01).

Table 1.

Results of the strain comparison in CO histochemistry across discrete regions of the brain of C58 and C57BL/6 mice. The STN was the only analyzed brain region to show a significant difference in CO staining optical density. STN samples from C58 mice had lower optical density values compared to STN samples from C57BL/6 mice, which suggests they have lower neuronal activation of the STN. Values are reported as mean (SEM).

| Optical density | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Brain region | C57BL/6 | C58 | p-value |

| Subthalamic nucleus (STN) | 0.139 (0.007) | 0.118 (0.004) | 0.012 |

| Globus pallidus (GP) | 0.068 (0.003) | 0.065 (0.003) | 0.511 |

| Striatum | 0.115 (0.006) | 0.109 (0.004) | 0.368 |

| Nucleus accumbens (NAcc) | 0.131 (0.009) | 0.125 (0.007) | 0.619 |

| Primary motor cortex (M1) | 0.121 (0.006) | 0.115 (0.005) | 0.449 |

| Substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) | 0.072 (0.003) | 0.070 (0.002) | 0.612 |

| Substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr) | 0.098 (0.005) | 0.097 (0.003) | 0.748 |

| Hippocampus | 0.101 (0.006) | 0.096 (0.003) | 0.459 |

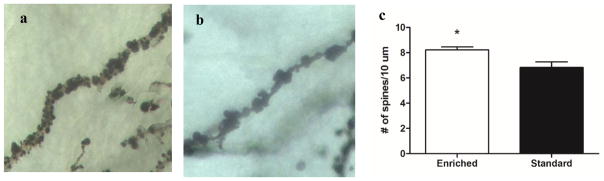

Golgi-Cox staining

For the analysis of dendritic spine density, we compared six male C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 2A) and five male C58 mice (Fig. 2B). Within this smaller cohort of mice we again found that the C58 mice showed significantly more repetitive behavior as revealed by a two-tailed t-test (t(9)=7.32, p<0.0001). Within the STN, dendritic spine density was significantly lower in the C58 mice than in the C57BL/6 mice (t(9)=2.96, p=0.016; Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Mouse strain comparison of STN dendritic spine density. (a) Example of C57BL/6 STN dendrite sample used for analysis. (b) Example of C58 STN dendrite sample used for analysis. (c) C58 mice have significantly lower dendritic spine density in the STN compared to C57BL/6 mice. Figure shows mean + SEM (* p<0.05).

Gene expression assays

For the analysis of gene expression differences in the STN between C58 and C57BL/6 mice, we used three male mice of each strain. Once again, this smaller cohort of mice showed significant differences in repetitive behavior, wherein C58 mice showed very high counts (t(4)=4.21, p=0.01). From the two PCR arrays, we found four genes that were differentially expressed between C58 and C57BL/6 STN samples with fold regulation greater than 1.3 (Table 2). Of these hits, none of the genes remained statistically significant after running the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure with a 20% FDR. For the analysis, C57BL/6 mice were treated as the control so negative fold regulation changes indicate lower gene expression in C58 mice.

Table 2.

Gene expression differences in the STN between C58 and C57BL/6 mice. Of the 148 genes analyzed, four were differentially expressed between C58 and C57BL/6 mice.

Study 2: F2 high and low repetitive motor behavior mice

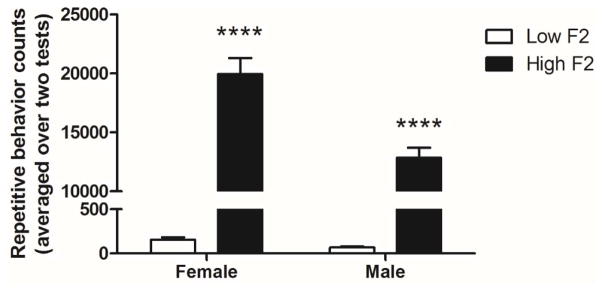

To substantiate further the role of STN neuronal activation in repetitive behavior we selected 12 F2 generation mice (six male, six female) with the highest repetitive behavior counts and 12 F2 mice (six male, six female) with the lowest repetitive behavior counts. This F2 generation was a product of C58 male x C57BL/6 female mating strategy and brother-sister mating of the F1 generation. A two-way ANOVA comparison of repetitive behavior counts for this cohort reveled a significant main effect of group (F(1,20)=403.9, p<0.0001), a main effect of sex (F(1,20)=19.66, p=0.0003), and a significant group x sex interaction (1,20)=18.72, p=0.0003; Figure 3). These results are reflected in the relatively lower repetitive behavior counts observed in male mice, particularly the F2 high males as compared to high females (see Fig. 3). Bonferroni post-tests confirmed significant group differences within both female and male comparisons (females, t=17.27, p<0.0001, males, t=11.15, p<0.0001)

Figure 3.

Average repetitive behavior counts across two behavioral tests of F2 mice. Female and male mice selected for high repetitive behavior counts were found to differ significantly from female and male mice selected for low repetitive behavior counts. Figure shows mean + SEM (****p<0.0001 for Bonferroni posttests).

Table 3 shows the CO staining optical density measures for the discrete brain regions for the high and low repetitive behavior F2 mice. It should be noted that the tissue from one female in the high repetitive behavior group was not included in the analysis due to a tissue processing error. The only statistically significant effect was found in the STN where high repetitive behavior F2 mice showed lower values than low repetitive behavior mice (F(1,19)=4.7, p=0.04). No significant effects of sex or group by sex interaction were found.

Table 3.

Optical density measurements of CO staining across discrete regions of the brain of high and low repetitive behavior F2 mice. The STN was the only analyzed brain region to show a significant difference in CO staining optical density. STN samples from high repetitive behavior F2 mice had lower optical density values compared to STN samples from low repetitive behavior F2 mice, which suggests they have lower neuronal activation of the STN. Values are reported as mean (SEM).

| Optical density | p-value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain region | Low female | High female | Low male | High male | Group | Sex | Interaction |

| STN | 0.096 (0.003) | 0.090 (0.003) | 0.102 (0.004) | 0.086 (0.007) | 0.043 | 0.936 | 0.312 |

| GP | 0.051 (0.003) | 0.053 (0.003) | 0.057 (0.005) | 0.049 (0.003) | 0.430 | 0.830 | 0.237 |

| Striatum | 0.072 (0.003) | 0.075 (0.003) | 0.084 (0.004) | 0.074 (0.003) | 0.325 | 0.170 | 0.082 |

| NAcc | 0.077 (0.005) | 0.088 (0.004) | 0.079 (0.009) | 0.079 (0.005) | 0.523 | 0.673 | 0.533 |

| M1 | 0.074 (0.004) | 0.074 (0.002) | 0.083 (0.005) | 0.072 (0.005) | 0.226 | 0.450 | 0.232 |

| SNc | 0.055 (0.002) | 0.054 (0.003) | 0.060 (0.005) | 0.049 (0.005) | 0.182 | 0.909 | 0.321 |

| SNr | 0.065 (0.004) | 0.068 (0.002) | 0.081 (0.006) | 0.063 (0.005) | 0.169 | 0.285 | 0.051 |

| Hippocampus | 0.070 (0.003) | 0.073 (0.004) | 0.082 (0.005) | 0.071 (0.003) | 0.318 | 0.232 | 0.093 |

Study 3: Effects of environmental enrichment

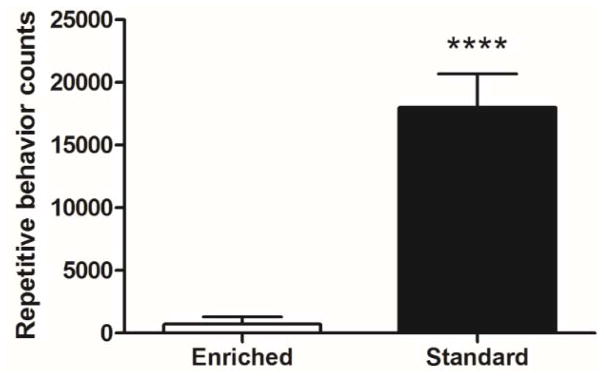

We tested a total of 21 C58 mice (seven females, 14 males), which were housed in environmental enrichment, and 20 C58 mice (two females, 18 males), which were housed in standard laboratory cages, for our analyses of neuronal activation, dendritic spine density, and gene expression. The repetitive behavior data for the mice used in the CO histochemistry experiment were included in our original report on the effectiveness of environmental enrichment to reduce repetitive behavior in C58 mice (t(22) = 5.62, p<0.0001; Muehlmann et al., 2012). Their brains were held over for this analysis of neuronal activation. The repetitive behavior expressed by the remaining mice (8 enriched males, 9 standard housed males), represent a similar substantial effect of environmental enrichment. A two-tailed t-test showed a significant reduction of repetitive behavior in C58 mice that were housed in enriched cages as compared to C58 mice housed in standard laboratory cages (t(15)=5.98, p<0.0001; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Housing comparison of repetitive behavior counts. Environmental enrichment significantly reduces the expression of repetitive behavior in C58 mice. Figure shows mean + SEM (**** p<0.0001).

CO histochemistry

Neuronal activation within discrete brain regions was analyzed by CO histochemistry in 13 C58 mice housed in environmental enrichment (seven females, six males) and in 11 C58 mice housed in standard laboratory cages (two females, nine males). Using two-tailed t-tests, we found no differences in the optical density of CO staining in any brain region analyzed (Table 4).

Table 4.

Optical density measurements in CO staining in the STN between enriched and standard housed C58 mice. There were no significant differences in CO staining in any of the analyzed brain regions. Values are reported as mean (SEM).

| Optical density | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Brain region | Enriched | Standard | p-value |

| STN | 0.093 (0.003) | 0.089 (0.005) | 0.424 |

| GP | 0.052 (0.002) | 0.051 (0.002) | 0.852 |

| Striatum | 0.077 (0.002) | 0.078 (0.002) | 0.629 |

| NAcc | 0.082 (0.002) | 0.078 (0.003) | 0.358 |

| M1 | 0.088 (0.002) | 0.089 (0.003) | 0.858 |

| SNc | 0.056 (0.002) | 0.057 (0.003) | 0.858 |

| SNr | 0.077 (0.002) | 0.078 (0.005) | 0.786 |

| Hippocampus | 0.075 (0.002) | 0.074 (0.002) | 0.518 |

Golgi-Cox staining

For the analysis of dendritic spine density in the STN, we compared five male C58 mice housed in environmental enrichment (Fig. 5A) and six male C58 mice housed in standard laboratory cages (Fig. 5B). Dendritic spine density was significantly higher in the STN samples of C58 mice housed in an enriched environment compared to C58 mice housed in standard laboratory cages (t(9)=2.64, p=0.027; Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Housing comparison of STN dendritic spine density. (a) Example of environmentally enriched C58 STN dendrite sample used for analysis. (b) Example of standard housed C58 STN dendrite sample used for analysis. (c) C58 mice housed in environmental enrichment have significantly higher dendritic spine density in the STN compared to C58 mice housed in standard laboratory cages. Figure shows mean + SEM (*p<0.05).

Gene expression

For the analysis of differential gene expression, we compared STN samples from three male C58 mice that were housed in an enriched environment and three male C58 mice that were housed in standard laboratory cages. From the two PCR arrays, we found 15 genes with differential expression that met statistical significance (Table 5). Of these hits, seven of the genes remained statistically significant after running the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure with a 20% FDR. For the analysis, standard housed mice were treated as the control so positive fold regulation changes indicate higher gene expression in environmentally enriched mice and negative fold regulation changes indicate lower gene expression in environmentally enriched mice.

Table 5.

Gene expression differences in the STN between C58 mice housed in an enriched environment and C58 mice housed in standard cages. Genes highlighted in bold font remained significant after the Benjamini-Hochburg procedure using a 20% FDR.

| Gene | RefSeq Number | Fold Regulation | Unadjusted p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eph receptor B2 (Ephb2) | NM_010142 | 1.48 | 0.002 |

| Grin1 (NR1) | NM_008169 | 1.41 | 0.004 |

| mGluR7 | NM_177328 | 1.42 | 0.004 |

| mGluR3 | NM_181850 | −1.26 | 0.005 |

| CaMKIIa | NM_177407 | 1.34 | 0.006 |

| Ppp3ca | NM_008913 | 1.31 | 0.007 |

| Early growth response 1 (Egr1) | NM_007913 | 2.27 | 0.01 |

| Homer1 | NM_152134 | −1.34 | 0.012 |

| Nitric oxide synthase 1 (Nos1) | NM_008712 | 1.94 | 0016 |

| NMDA-2D (NR2D) | NM_008172 | 1.58 | 0.017 |

| Slc1a3 – glial glutamate transporter | NM_148938 | −1.53 | 0.02 |

| GABAA α2 | NM_008066 | −1.34 | 0.026 |

| GluR2 | NM_013540 | 1.47 | 0.041 |

| mGluR2 | NM_001160353 | 1.37 | 0.045 |

| GluR4 | NM_019691 | 1.3 | 0.045 |

DISCUSSION

Our previous work in the deer mouse model indicated that dysregulation of indirect basal ganglia pathway function contributes to the expression of repetitive behavior in that model (Bechard et al., 2016; Bechard et al., 2017; Presti & Lewis, 2005; Tanimura et al., 2010; Tanimura et al., 2011). The present study was designed to elucidate the cellular and molecular differences within the STN, a key relay nucleus in basal ganglia circuitry, between mice with high rates of repetitive behavior and mice with low rates of repetitive behavior. We replicated our previous findings (Muehlmann et al., 2012) by demonstrating a robust difference in repetitive behavior counts between C58 mice and C57BL/6 mice and the substantial effect that environmental enrichment has on reducing the repetitive behavior of C58 mice.

In our cellular and molecular analyses in C58 and C57BL/6 mice, we found several differences that suggest the STN has lower afferent glutamatergic tone in C58 mice. Glutamatergic inputs to the STN are monosynaptic cortical projections and make up the hyperdirect basal ganglia pathway. First, our measure of neuronal activation, assayed by CO histochemistry, showed significantly lower levels in the STN of C58 mice. Dendrites that receive depolarizing inputs, such as glutamatergic afferents from the hyperdirect basal ganglia pathway, are the site of dense mitochondria clustering and have high levels of cytochrome oxidase activity (Wong-Riley, 1989). This metabolic machinery is required to return the cell membrane to resting potential after depolarization (Attwell & Laughlin, 2001). Hyperpolarizing inputs, such as GABAergic afferents from the GPe (i.e. the indirect basal ganglia pathway), are not as energetically demanding (Chatton et al., 2003; Waldvogel et al., 2000). The lower CO activity measures in the STN of C58 mice suggests less glutamatergic input as compared to the STN of C57BL/6 mice. Lower CO activity in the STN of C58 mice corresponds to our other finding that CO activity was lower in the high repetitive behavior subgroup of F2 mice, when compared to STN samples from the low repetitive behavior subgroup. In addition, we found that lower CO activity is not characteristic of all C58 brain regions and is not due to strain-specific differences. No other brain regions that we analyzed in either the strain experiment or the F2 experiment showed differences in CO activity.

The second piece of evidence that suggests hypoglutamatergic afferent tone in the STN is our finding that STN neurons of C58 mice have fewer dendritic spines. Glutamatergic neurotransmission causes plastic changes in dendritic morphology, including spine formation, maturation, and remodeling. GABAergic inputs, like those from the GPe, do not synapse on dendritic spines. Our finding of fewer dendritic spines in the STN samples of C58 mice, when compared to C57BL/6 mice, is consistent with our finding that synaptopodin gene expression is lower in STN samples of C58 mice (though this did not meet the FDR adjusted p-value). Synaptopodin is an actin binding protein localized in the neck of dendritic spines that associates with calcium stores and regulates plasticity at glutamatergic synapses (Segal et al, 2010).

Other gene expression differences between C58 and C57BL/6 mice that were below the standard alpha level, but were not below the adjusted Benjamini-Hochberg p-value, also suggest hypoglutamatergic tone within the STN in C58 mice. These include downregulation of both cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) and JunB. Glutamatergic signaling through NMDA receptors activates nitric oxide synthase, causing the release of nitric oxide, which activates PKG and causes an increase in JunB expression (Haby et al., 1994).

Our analyses of GABAergic genes returned only one gene with differential expression between C58 and C57BL/6 mice, the GABAA α2 subunit gene. As with the other gene expression differences in our C58 and C57BL/6 comparison, the unadjusted p-value was below alpha but above the adjusted Benjamini-Hochberg p-value. To our knowledge, GABAA α2 expression has not been assayed by qPCR in the STN, but expression of this subunit in the STN has been confirmed with immunocytochemistry in the adult rat (Schwarzer et al, 2001). We found that expression of the α2 subunit is increased in the STN of C58 mice compared to C57BL/6 mice. GABAA α2 containing receptors are particularly important for fast phasic inhibitory postsynaptic currents at somatic synapses (Presonil et al., 2006). This overexpression of α2 may be a homeostatic response to the hypoglutamatergic afferent tone, as fast GABAergic signaling has been shown to increase electrically-stimulated excitatory postsynaptic potential amplitude and lower action potential threshold in the STN (Baufreton et al, 2005).

The robust effect of environmental enrichment-induced reduction on repetitive behavior in C58 mice provides a mechanism by which we can investigate cellular and molecular changes that correspond with changes in behavior and potentially find new drug targets for treatment. The preponderance of STN gene expression differences induced by environmental enrichment are consistent with an increase in glutamatergic afferent tone. A particular mechanism that may directly affect synaptic glutamate levels is the reduction of the glial glutamate transporter, GLAST (though the unadjusted p-value was above the Benjamini-Hochberg p-value). Reduced glutamate transport changes AMPA receptor activation signatures, including excitatory postsynaptic current amplitude and decay latencies (Marcaggi et al., 2003; Stoffel et al., 2004), such that the postsynaptic neuron stays in a depolarized state longer following stimulation. Our measures of STN gene expression also showed increased transcription of AMPA receptor subunit mRNA, namely GluR2 and GluR4, and NMDA receptor subunit mRNA, NR1 (which did meet the Benjamini-Hochberg criterion p-value) and NR2D, in the environmental enrichment group. NR2D containing NMDA receptors control spike-firing rate in the STN (Swanger et al., 2015) and increased expression suggests STN output is enhanced in mice raised in an enriched environment. Consistent with enhanced signaling of these ionotropic glutamate receptors, we found increased CamKIIa, nitric oxide synthase, and Egr1 gene expression in the STN samples of the C58 mice housed in environmental enrichment (though nitric oxide synthase did not meet the Benjamini-Hochberg criterion p-value). Interestingly, nitric oxide signaling can both enhance glutamatergic stimulation and reduce GABAergic inhibition of STN neurons (Sardo et al., 2009). In addition, long-term housing in an enriched environment has been shown to increase the expression of Egr1 previously, though these investigations have been limited to regions of the cortex and hippocampus (Olsson et al., 1994; Pinaud et al., 2002). In fact, a wide array of environmental manipulations has been shown to affect neuronal activity and intracellular signaling pathways that increase Egr1 expression in the short term, which is followed by Egr1 transcription factor functions that mediate longer lasting neuronal adaptations (Duclot and Kabbaj, 2017). These neuronal adaptations include increases in dendritic spine density (Xie et al., 2013), an effect we also saw in the STN samples of mice raised in an enriched environment. Another interesting gene expression difference in the enriched environment mice that links glutamatergic function and dendritic spine density is the increased expression of the EphB2 receptor (which met the adjusted Benjamini-Hochberg criterion for significance). Stimulation of EphB2 receptors enhances NMDA and AMPA receptor clustering in dendritic spines and is a key regulator of synaptic plasticity (Hussain et al., 2015; Nolt et al., 2011).

Some of the gene expression differences we found in the environmental enrichment group suggest that the increased afferent glutamatergic tone sufficiently stimulated the STN neurons and increased their release of glutamate (this includes NR2D expression mentioned above). We found increased expression of mGluR2 (though this did not reach the Benjamini-Hochberg significance criterion) and mGluR7 mRNA in the environmental enrichment group compared to the standard housed group. The mGluR2 and mGluR7 are presynaptic receptors that function as autoreceptors on STN axon terminals to reduce glutamate release in the SNr, typically in response to excess synaptic glutamate levels (Bradley et al., 2000; Wittmann et al., 2001). In addition, we found a decrease in the expression of mGluR3 in the STN samples from mice raised in an enriched environment (which was significant at the adjusted Benjamini-Hochberg criterion). The mGluR3 receptor is found primarily in glial cells in the STN (Testa et al., 1994) and extended exposure to an agonist decreases mGluR3 protein levels (Durand et al., 2010). Taken together, the increase in mGluR2 and mGluR7 mRNA and decrease in mGluR3 mRNA may indicate a homeostatic response to enhanced glutamate release from and on to STN neurons of environmentally enriched mice.

Furthermore, environmental enrichment corrected the differential gene expression of GABAA α2. Our comparison of C58 and C57BL/6 mice revealed upregulation of this GABAA receptor subunit in the STN samples of C58 mice. Environmental enrichment decreased its expression (though this did not reach the Benjamini-Hochberg significance criterion). This is the only individual gene tested that was differentially regulated in both of our comparisons.

The functional consequence of these differentially expressed genes will need to be followed up with protein and phospho-protein assays. Two other genes that were different between the standard and enrichment groups were Homer1 and PPP3ca. Homer1 expression was lower in the STN samples of enriched mice (though not at the adjusted Benjamini-Hochberg criterion). It is unclear what functional significance this difference may offer as Homer1 is just one of three in the Homer adaptor protein family and compensatory activity of the other Homer proteins may have occurred. Unfortunately, our PCR arrays did not include the Homer2 or Homer3 genes. PPP3ca is one isoform of the catalytic subunit of calcineurin. We found a significant increase in PPP3ca expression in STN samples of enriched mice. Again, whether or not this difference in expression has a functional consequence in STN samples is unclear. Gene primers for the other two catalytic isoforms, PPP3cb and PPP3cc, were also not included in the PCR array. Calcineurin plays a large role in experience-dependent plasticity and future work should focus on which effect of calcineurin (e.g. reducing mGluR5 desensitization (Alagarsamy et al., 2005) or suppressing GABAA function (Chen & Wong, 1995)) may contribute to the environmental enrichment-induced reduction of repetitive behavior.

Given the number of glutamate-related genes that were differentially expressed, which suggest increased glutamatergic tone following environmental enrichment, it is surprising that our analysis of CO activity was not changed. Findings of dissociated CO activity and other measures of neuronal activity such as 2-deoxyglucose uptake or immediate early gene expression have been reported (Braun et al., 1985; Takahata, 2016). It is also possible that our staining method was not sensitive enough to find a change in optical density at the distal dendrites of STN neurons where glutamatergic afferents synapse.

There are several limitations associated with these studies. The differences in spine density and gene expression reported here occur in the STN. Although alterations in this nucleus support a role for the mediation of repetitive behavior by the hyperdirect and indirect basal ganglia pathways, such a conclusion would require examination of additional brain regions involved in these pathways (e.g. motor cortex, GP) as well as negative control regions. Other methodologies such as optogenetic and chemogenetic techniques would be needed to determine more definitively the roles of these pathways. We were also not able to systematically test for sex differences in all the experiments. Future experiments will need to involve both male and female mice and utilize sample sizes that provide sufficient power to determine interactions of sex with other key independent variables.

Finally, our findings implicating an important role for the STN in repetitive behavior are consistent with reports from studies of relevant clinical populations and other animal models. For example, in addition to suppressing repetitive movements in Parkinson’s disease (e.g. levodopa-induced dyskinesia), deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the STN reduced the severity of symptoms in previously treatment refractory OCD patients (Burdick et al., 2009). In animal models, pharmacological induction of stereotyped motor behavior in non-human primates was attenuated by DBS of the STN (Baup et al., 2008; Grabli et al., 2004). In rats, bilateral high frequency stimulation of STN as well as pharmacological inactivation of STN reduced quinpirole-induced compulsive checking (Klavir et al., 2009; Winter et al., 2008a,b). High frequency stimulation of STN also reduced excessive self-grooming in two mouse models relevant to ASD (Chang et al., 2016). This works also follows from the rich literature on the role of the STN in behavioral inhibition. Normal function of the STN is thought to be important for inhibiting behaviors that are inconsistent with goal-directed behavior (Jahanshahi et al., 2015; Mink, 1996) and increasing STN firing rate with optogenetic stimulation can inhibit even goal directed behaviors (Fife et al., 2017). Furthermore, lesioning the STN impairs stopping behavior in a go-trial reaction time task and increases spontaneous locomotion (Eagle et al., 2008). Taken together, these findings and the ones reported here suggest an important role for the STN in the mediation of repetitive behavior, which may be a product of a generalized deficit of behavioral inhibition.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Information figure S1. Example sagittal slice after cytochrome oxidase histochemistry demonstrating boundary tracings used for striatum, globus pallidus (GP), subthalamic nucleus (STN), and substantia nigra pars reticulate (SNr).

Supporting Information figure S2. Example coronal slice after Golgi-Cox impregnation demonstrating boundary tracing used for the STN dendritic spine density analysis.

Supporting Information video S1. Sample video of a C58 mouse exhibiting repetitive hindlimb jumping.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under University of Florida Clinical and Translational Science Awards KL2 TR000065 and UL1 TR000064. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Alagarsamy S, Saugstad J, Warren L, Mansuy IM, Gereau RW, IV, Conn PJ. NMDA-induced potentiation of mGluR5 is mediated by activation of protein phosphatase 2B/calcineurin. Neuropharmacol. 2005;49:135–145. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwell D, Laughlin SB. An energy budget for signaling in the grey matter of the brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:1133–1145. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200110000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baufreton J, Atherton JF, Surmeier DJ, Bevan MD. Enhancement of excitatory synaptic integration by GABAergic inhibition in the subthalamic nucleus. J Neurosci. 2005;37:8505–8517. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1163-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baup N, Grabli D, Karachi C, Mounayar S, Francois C, Yelnik J, Feger J, Tremblay L. High-frequency stimulation of the anterior subthalamic nucleus reduces stereotyped behaviors in primates. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8785–8788. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2384-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechard AR, Bliznyuk N, Lewis MH. The development of repetitive motor behaviors in deer mice, Effects of environmental enrichment, repeated testing, and differential mediation by indirect basal ganglia pathway activation. Dev Psychobiol. 2017;59:390–399. doi: 10.1002/dev.21503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechard AR, Cacodcar N, King MA, Lewis MH. How does environmental enrichment reduce repetitive behaviors? Neuronal activation and dendritic morphology in the indirect basal ganglia pathway of a mouse model. Behav Brain Res. 2016;299:122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechard A, Lewis M. Modeling Restricted Repetitive Behavior in Animals. Autism. 2012:S1-006. doi: 10.4172/2165-7890. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bodfish JW, Symons FJ, Parker DE, Lewis MH. Varieties of repetitive behavior in autism, comparisons to mental retardation. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30:237–243. doi: 10.1023/a:1005596502855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley SR, Marino MJ, Wittmann M, Rouse ST, Awad H, Levey AI, Conn PJ. Activation of group II metabotropic glutamate receptors inhibits synaptic excitation of the substantia nigra pars reticulata. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3085–3094. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-09-03085.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun K, Scheich H, Schachner M, Heizmann CW. Distribution of parvalbumin, cytochrome oxidase activity and 14C-2-deoxyglucose uptake in the brain of the zebra finch. Cell Tissue Res. 1985;240:101–115. [Google Scholar]

- Burdick A, Goodman WK, Foote KD. Deep brain stimulation for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Front Biosci. 2009;14:1880–1890. doi: 10.2741/3348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cath DC, Spinhoven P, Hoogduin CA, van Woerkom TC, van de Wetering BJ, Roos RA, Rooijmans HG. Repetitive behaviors in Tourette’s syndrome and OCD with and without tics, what are the differences? Psych Res. 2001;101:171–85. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang AD, Berges VA, Chung SJ, Fridman GY, Baraban JM, Reti IM. High-frequency stimulation at the subthalamic nucleus suppresses excessive self-grooming in autism-like mouse models. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;41:1813–1821. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatton JY, Pellerin L, Magistretti PJ. GABA uptake into astrocytes is not associated with significant metabolic cost, Implications for brain imaging of inhibitory transmission. PNAS. 2003;100:12456–12461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2132096100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen QX, Wong RKS. Suppression of GABAA receptor responses by NMDA application in hippocampal neurons acutely isolated from the adult guinea-pig. J Physiol. 1995;482:353–362. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipriani G, Vedovello M, Ulivi M, Nuti A, Lucetti C. Repetitive and stereotypic phenomena and dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2013;28:223–227. doi: 10.1177/1533317513481094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duclot F, Kabbaj M. The role of early growth response 1 (EGR1) in brain plasticity and neuropsychiatric disoders. Front Behav Neurosci. 2017;11:35. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2017.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand D, Caruso C, Carniglia L, Lasaga M. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 3 activation prevents nitric oxide-induced death in cultured rat astrocytes. J Neurochem. 2010;112:420–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazzi E, Lanners J, Danova S, Ferrarri-Ginevra O, Gheza C, Luparia A, Balottin U, Lanzi G. Stereotyped behaviours in blind children. Brain & Dev. 1999;21:522–528. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(99)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fife KH, Gutierrez-Reed NA, Zell V, Bailly J, Lewis CM, Aron AR, Hnasko TS. Causal role for the subthalamic nucleus in interrupting behavior. eLife. 2017;6:e27689. doi: 10.7554/eLife.27689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher L, Ames EW, Chisholm K, Savoie L. Problems reported by parents of Romanian orphans adopted to British Colombia. Int J Behav Dev. 1997;20:67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Lima F, Cada A. Quantitative histochemistry of cytochrome oxidase activity, Theory, methods, and regional brain vulnerability. In: Gonzalez-Lima F, editor. Cytochrome oxidase in neuronal metabolism and Alzheimer’s Disease. Plenum Press; New York: 1998. pp. 55–90. [Google Scholar]

- Grabli D, McCairn K, Hirsch EC, Agid Y, Feger J, Francois C, Tremblay L. Behavioural disorders induced by external globus pallidus dysfunction in primates, I. Behavioural study. Brain. 2004;127:2039–2054. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haby C, Lisovoski F, Aunis D, Zwiller J. Stimulation of the cyclic GMP pathway by NO induces expression of the immediate early genes c-fos and junB in PC12 cells. J Neurochem. 1994;62:496–501. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62020496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley C, Hadley B, Ephraim S, Yang M, Lewis MH. Spontaneous stereotypy and environmental enrichment in deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus): Reversibility of experience. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2006;97:312–322. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain NK, Thomas GM, Luo J, Huganir RL. Regulation of AMPA receptor subunit GluA1 surface expression by PAK3 phosphorylation. PNAS. 2015;112:E5883–5890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518382112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahanshahi M, Obeso I, Rothwell JC, Obeso JA. A fronto-striato-subthalamic-pallidal network for goal-directed and habitual inhibition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16:719–732. doi: 10.1038/nrn4038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalueff AV, Stewart AM, Song C, Berridge KC, Graybiel AM, Fentress JC. Neurobiology of rodent self-grooming and its value for translational neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17:45–59. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2015.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klavir O, Flash S, Winter C, Joel D. High frequency stimulation and pharmacological inactivation of the subthalamic nucleus reduces ‘compulsive’ lever-pressing in rats. Exp Neurol. 2009;215:101–9. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leekam SR, Prior MR, Uljarevic M. Restricted and repetitive behaviors in autism spectrum disorders, a review of research in the last decade. Psychol Bull. 2011;137:562–593. doi: 10.1037/a0023341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MH, Kim SJ. The pathophysiology of restricted repetitive behavior. J Neurodev Disord. 1:114–132. doi: 10.1007/s11689-009-9019-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MH, Bodfish JW. Repetitive behavior disorders in autism. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 1998;4:80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Marcaggi P, Billups D, Attwell D. The role of glial glutamate transporters in maintaining the independent operation of juvenile mouse cerebellar parallel fibre synapses. J Physiol. 2003;552:89–107. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.044263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mink JW. The basal ganglia: Focused selection and inhibition of competing motor programs. Prog Neurobiol. 1996;50:381–425. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(96)00042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss J, Oliver C, Arron K, Burbidge C, Berg K. The prevalence and phenomenology of repetitive behavior in genetic syndromes. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39:572–588. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0655-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moy SS, Nadler JJ, Young NB, Nonneman RJ, Segall SK, Andrade GM, Magnuson TR. Social approach and repetitive behavior in eleven inbred mouse strains. Behav Brain Res. 2008;191:118–129. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muehlmann AM, Edington G, Mihalik AC, Buchwald Z, Koppuzha D, Korah M, Lewis MH. Further characterization of repetitive behavior in C58 mice, developmental trajectory and effects of environmental enrichment. Behav Brain Res. 2012;235:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolt MJ, Lin Y, Hruska M, Murphy J, Sheffler-Colins SI, Kayser MS, Passer J, Bennett MVL, Zukin RS, Dalva MB. EphB controls NMDA receptor function and synaptic targeting in a subunit-specific manner. J Neurosci. 2011;31:5353–5364. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0282-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyatsanza S, Shetty T, Gregory C, Lough S, Dawson K, Hodges JR. A study of stereotypic behaviours in Alzheimer’s disease and frontal and temporal variant frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:1398–1402. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.10.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson T, Mohammed AH, Donaldson LF, Henriksson BG, Seckl JR. Glucocorticoid receptor and NGFI-A gene expression are induced in the hippocampus after environmental enrichment in adult rats. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1994;23:349–353. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinaud R, Tremere LA, Penner MR, Hess FF, Robertson HA, Currie RW. Complexity of sensory environment drives the expression of candidate-plasticity gene, nerve growth factor induced-A. Neurosci. 2002;112:573–582. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell SB, Newman HA, McDonald TA, Bugenhagen P, Lewis MH. Development of spontaneous stereotyped behavior in deer mice: Effects of early and late exposure to a more complex environment. Dev Psychobiol. 2000;37:100–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prenosil GA, Schneider Gasser EM, Rudolph U, Keist R, Fritschy JM, Vogt KE. Specific subtypes of GABAA receptors mediate phasic and tonic forms of inhibition in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:846–857. doi: 10.1152/jn.01199.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presti MF, Lewis MH. Striatal opioid peptide content in an animal model of spontaneous stereotypic behavior. Behav Brain Res. 2005;157:363–368. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prioni S, Fetoni V, Barocco F, Redaelli V, Falcone C, Soliveri P, Girotti F. Stereotypic behaviors in degenerative dementias. J Neurol. 2012;259:2452–2459. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6528-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Andersen-Wood L, Beckett C, Bredenkamp D, Castle J, Groothues C, Kreppner J, Keaveney L, Lord C, O’Connor TG the English Romanian Adoptees (ERA) Study Team. Quasi-autistic patterns following severe early global privation. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40:537–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan BC, Young NB, Crawley JN, Bodfish JW, Moy SS. Social deficits, stereotypy and early emergence of repetitive behavior in the C58/J inbred mouse strain. Behav Brain Res. 2010;208:178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata JT, Crews D, Gonzalez-Lima F. Behavioral correlates of differences in neural metabolic activity. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;48:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardo P, Carletti F, D’Agostino S, Rizzo V, La Grutta V, Ferraro G. Intensity of GABA-evoked responses is modified by nitric oxide-active compounds in the subthalamic nucleus of the rat, A microiontophoretic study. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:2340–2350. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer C, Berresheim U, Pirker S, Wieselthaler A, Fuchs K, Sieghart W, Sperk G. Distribution of the major gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor subunits in the basal ganglia and associated limbic brain areas of the adult rat. J Comp Neurol. 2001;433:526–549. doi: 10.1002/cne.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal M, Vlachos A, Korkotian E. The spine apparatus, synaptopodin, and dendritic spine plasticity. Neuroscientist. 2010;16:125–131. doi: 10.1177/1073858409355829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer HS. Motor control, habits, complex motor stereotypies, and Tourette syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1304:22–31. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoffel W, Korner R, Wachtmann D, Keller BU. Functional analysis of glutamate transporters in excitatory synaptic transmission of GLAST1 and GLAST1/EAAC1 deficient mice. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2004;128:170–181. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanger SA, Vance KM, Pare JF, Sotty F, Fog K, Smith Y, Traynelis SF. NMDA receptors containing the GluN2D subunit control neuronal function in the subthalamic nucleus. J Neurosci. 2015;35:15971–15983. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1702-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahata T. What does cytochrome oxidase histochemistry represent in the visual cortex? Front Neuroanat. 2016;10:79. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2016.00079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanimura Y, King MA, Williams DK, Lewis MH. Development of repetitive behavior in a mouse model, Roles of indirect and striosomal basal ganglia pathways. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2011;29:461–467. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanimura Y, Vaziri S, Lewis MH. Indirect basal ganglia pathway mediation of repetitive behaviour, Attenuation by adenosine receptor agonists. Behav Brain Res. 2010;210:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa CM, Standaert DG, Young AB, Penney JB., Jr Metabotropic glutamate receptor mRNA expression in the basal ganglia of the rat. J Neurosci. 1994;14:3005–3018. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-03005.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynor JM, Hall GB. Structural and functional neuroimaging of restricted and repetitive behavior in autism spectrum disorder. Intellect Disabl Diagn J. 2015;3:21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Turner CA, Lewis MH. Environmental enrichment, effects on stereotyped behavior and neurotrophin levels. Physiol Behav. 2003;80:259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2003.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CA, Lewis MH, King MA. Environmental enrichment, Effects on stereotyped behavior and dendritic morphology. Dev Psychobio. 2003;43:20–27. doi: 10.1002/dev.10116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CA, Yang MC, Lewis MH. Environmental enrichment, effects on stereotyped behavior and regional neuronal metabolic activity. Brain Res. 2002;938:15–21. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02472-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldvogel D, van Gelderen P, Muelbacher W, Ziemann U, Immisch I, Hallett M. The relative metabolic demand of inhibition and excitation. Nature. 2000;406:995–998. doi: 10.1038/35023171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse CM, Curry-Pochy LS, Shafer R, Rudy J, Lewis MH. Reversal learning in C58 mice, Modeling higher order repetitive behavior. Behav Brain Res. 2017;332:372–378. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2017.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse CM, Lewis MH. Repetitive behavior in neurodevelopmental disorders, Clincial and translational finding. Behav Anal. 2015;38:163–178. doi: 10.1007/s40614-015-0029-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter C, Flash S, Klavir O, Klein J, Sohr R, Joel D. The role of the subthalamic nucleus in “compulsive” behavior in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2008a;27:1902–1911. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter C, Mundt A, Jalali R, Joel D, Harnack D, Morgenstern R, Juckel G, Kupsch A. High frequency stimulation and temporary inactivation of the subthalamic nucleus reduce quinpirole-induced compulsive checking behavior in rats. Exp Neurol. 2008b;210:217–228. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann M, Marino MJ, Bradley SR, Conn PJ. Activation of group III mGluRs inhibits GABA-ergic and glutamatergic transmission in the substantia nigra pars reticulata. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:1960–1968. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.5.1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong-Riley MT. Cytochrome oxidase, an endogenous metabolic marker for neuronal activity. Trends Neurosci. 1989;12:94–101. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong-Riley MTT, Nie F, Hevner RF, Liu S. Brain cytochrome oxidase, Functional significance and biogenomic regulation in the CNS. In: Gonzalez-Lima F, editor. Cytochrome oxidase in neuronal metabolism and Alzheimer’s Disease. Plenum Press; New York: 1998. pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Xie L, Korkmaz KS, Braun K, Bock J. Early life stress-induced histone acetylations correlate with activation of the synaptic plasticity genes Arc and Egr1 in the mouse hippocampus. J Neurochem. 2003;125:457–464. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information figure S1. Example sagittal slice after cytochrome oxidase histochemistry demonstrating boundary tracings used for striatum, globus pallidus (GP), subthalamic nucleus (STN), and substantia nigra pars reticulate (SNr).

Supporting Information figure S2. Example coronal slice after Golgi-Cox impregnation demonstrating boundary tracing used for the STN dendritic spine density analysis.

Supporting Information video S1. Sample video of a C58 mouse exhibiting repetitive hindlimb jumping.