Abstract

Aim: Sitosterolemia is an extremely rare, autosomal recessive disease characterized by high plasma cholesterols and plant sterols because of increased absorption of dietary cholesterols and sterols from the intestine, and decreased excretion from biliary tract. Previous study indicated that sitosterolemic patients might be vulnerable to post-prandial hyperlipidemia, including high remnant-like lipoprotein particles (RLP) level. Here we evaluate whether a loading dietary fat increases a post-prandial RLP cholesterol level in sitosterolemic patients compared to heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemic patients (FH).

Methods: We recruit total of 20 patients: 5 patients with homozygous sitosterolemia, 5 patients with heterozygous sitosterolemia, and 10 patients with heterozygous FH as controls from May 2015 to March 2018 at Kanazawa University Hospital, Japan. All patients receive Oral Fat Tolerance Test (OFTT) cream (50 g/body surface area square meter, orally only once, and the cream includes 34% of fat, 74 mg of cholesterol, and rich in palmitic and oleic acids. The primary endpoint is the change of a RLP cholesterol level after OFTT cream loading between sitosterolemia and FH. We measure them at baseline, and 2, 4, and 6 hours after the oral fat loading.

Results: This is the first study to evaluate whether sitosterolemia patients have a higher post-prandial RLP cholesterol level compared to heterozygous FH patients.

Conclusion: The result may become an additional evidence to restrict dietary cholesterols for sitosterolemia. This study is registered at University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN ID: UMIN000020330).

Keywords: Sitosterolemia, Familial hypercholesterolemia, Post-prandial hyperlipidemia

Introduction

Sitosterolemia (OMIM #210250) is an extremely rare, autosomal recessive disease characterized by high plasma plant sterols because of increased absorption of dietary sterols from the intestine, and decreased excretion of sterols from biliary tract1). Sitosterolemic patients also have a higher plasma low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level, tendon xanthomas, premature atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease (CAD)2–5), resembling familial hypercholesterolemia (FH)6–8). FH is mainly caused by loss-of-function variants in LDLR gene9, 10).On the other hand, inactivating variants in ATP-binding cassette transporter G5 (ABCG5) and G8 (ABCG8) genes cause sitosterolemia1, 11).

Recently, we reported several sitosterolemic patients12), including infants with extremely high LDL-C levels after breastfeeding13). This report indicates that patients with sitosterolemia might be vulnerable to post-prandial hyperlipidemia, especially high remnant-like particle (RLP) levels. RLP levels are known as a rapid marker to evaluate lipid metabolism after diet14, 15). Also, increased RLP levels are associated with high LDL-C, endothelium dysfunction, and CAD16–18). Thus, this post-prandial condition may play an important role of plasma high LDL-C levels and promoteatherosclerosis for sitosterolemic patients. However, it has not been clear whether the post-prandial high RLP levels truly exist in sitosterolemia patients.

Here, we evaluate for the first time whether a loading dietary fat increases post-prandial high RLP levels in patients having sitosterolemia compared with those having FH.

Methods

Study Design

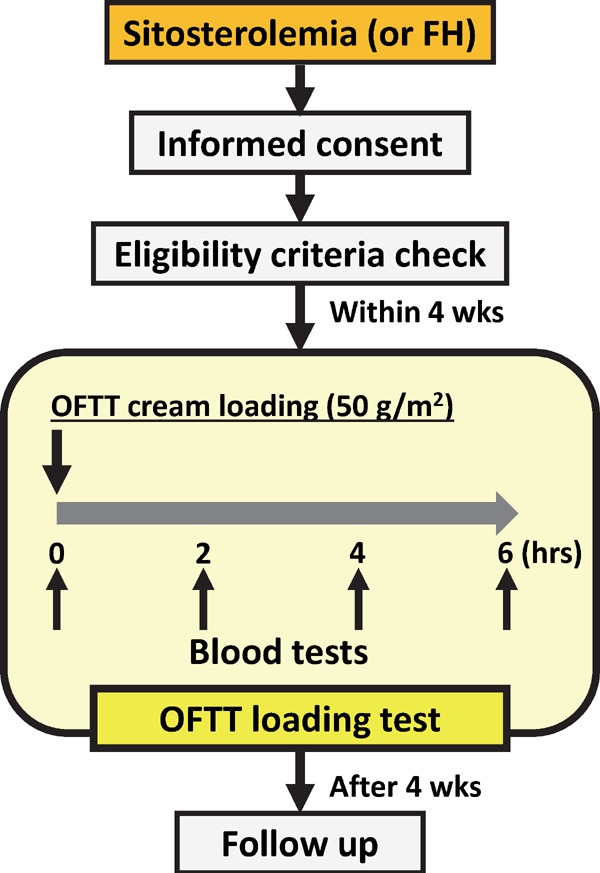

This study is a single arm, non-randomized, open label, uncontrolled trial. Patients with homozygous sitosterolemia, heterozygous sitosterolemia, and heterozygous FH are enrolled. Heterozygous FH patients are used as controls to arrange baseline cholesterol levels in this study. They receive an Oral Fat Tolerance Test (OFTT) cream when inclusion criteria are met. We then compare post-prandial plasma RLP cholesterol levels between homozygous sitosterolemia, heterozygous sitosterolemia, and heterozygous FH. We also assess the adverse effects of the test after 4 weeks (Fig. 1). Overall assessment protocol of this study is shown in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Scheme of this study protocol

Abbreviations: FH, familial hypercholesterolemia; hrs, hours; OFTT, Oral Fat Tolerance Test; wks, weeks.

Table 1. Assessment and evaluation schedule of this study.

| Assessments | Pre-loading period 4 wks prior to test | OFTT loading test |

Post-loading period 4 wks after test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 hr (loading) | 2 hrs | 4 hrs | 6 hrs | |||

| Informed consent | x | |||||

| Eligibility criteria check | x | |||||

| Adverse event check | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Blood pressure | x | x | x | x | ||

| Heart rate | x | x | x | x | ||

| Body weight | x | x | x | |||

| Blood test (lipid metabolism) | ||||||

| Total cholesterol | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Triglycerides | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| HDL cholesterol | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| LDL cholesterol | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| RLP cholesterol | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| RLP triglyceride | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Sitosterol | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Lathosterol | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Campesterol | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| ApoA-I | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| ApoA-II | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Apo-B | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| ApoC-II | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| ApoC-III | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| ApoE | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Blood test (CBC, Chemistry) | ||||||

| White blood cell | x | x | x | |||

| Red blood cell | x | x | x | |||

| Hemoglobin | x | x | x | |||

| Hematocrit | x | x | x | |||

| Platelet counts | x | x | x | |||

| AST | x | x | x | |||

| ALT | x | x | x | |||

| y-GTP | x | x | x | |||

| BUN | x | x | x | |||

| Creatinine | x | x | x | |||

| Albumin | x | x | x | |||

| Uric acid | x | x | x | |||

| Na, K, Cl, Ca, P | x | x | x | |||

| High sensitivity CRP | x | x | x | |||

| Symptoms | x | x | x | x | x | x |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CBC, complete blood count; Cr, creatinine; CRP, C-reactive protein; γ-GTP, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; OFTT, Oral Fat Tolerance Test; RLP, remnant-like lipoprotein particle.

We recruit sitosterolemia and FH patients from May 2015 to March 2018, or until the enrollments completed. This study is registered at University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN ID: UMIN000020330).

We conduct this study in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects, and all other applicable laws and guidelines in Japan. This protocol was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) at the Kanazawa University Hospital.

Study Participants

We include the patients who meet all the inclusion criteria (Table 2). Patients with either of the exclusion criteria are excluded from this study (Table 3). We obtain written informed consents from all the study participants. For children's participation, we prepare a parental consent form to obtain their parental or guardian's permissions. These consent forms were approved by IRB. The study participants must sufficiently understand the contents of the consent form before his/her acceptance. It must be dated and signed by both the participants and investigators. We also inform participants that their medical care will not be affected if they refuse to enroll in this study. We store these consent forms at Kanazawa University Graduate School of Medicine. Participants can drop from this study whenever they want to discontinue the study.

Table 2. Inclusion criteria.

| We include the patients with all the following criteria: |

| 1) Age 6 years or greater |

| 2) Patient who can provide written informed consent |

| 3) Outpatients at the Kanazawa University Hospital |

Table 3. Exclusion criteria.

| We exclude the patients with either of the following criteria: |

| 1) Anemia |

| 2) Lactose intolerance |

| 3) Allergy for the contents of OFTT cream |

| 4) Receiving immunosuppressive therapy |

| 5) Myocardial infarction or unstable angina |

| 6) Liver dysfunction (AST or ALT 100 IU/L or greater) |

| 7) Renal dysfunction (BUN 25 mg/dL or greater, or Cr 2.0 mg/dL or greater) |

| 8) Female with pregnancy or expected |

| 9) Patients whose doctors in charge consider him/her inappropriate to participate |

Abbreviations as Table 1.

Definitions of Diseases

Sitosterolemia diagnostic criteria19, 20):

-

Clinical diagnosis criteria:

Patients with all the following criteria:-

1)Plasma sitosterol level of ≥ 10 µg/mL

-

2)Tendon xanthoma or xanthoma tuberosum

-

1)

-

Genetic diagnosis criteria:

Loss-of-function variants in ABCG5/ABCG8 genes-

B-1)Heterozygous sitosterolemia: heterozygous loss-of-function variant in the genes

-

B-2)Homozygous sitosterolemia (true sitosterolemia): True homozygous, compound heterozygous, or double heterozygous loss-of-function variants in the genes

Patients who meet both A and B-1 are defined as heterozygous sitosterolemia.

Patients who meet both A and B-2 are defined as homozygous sitosterolemia.

-

B-1)

Heterozygous FH diagnostic criteria21, 22):

-

Clinical diagnosis criteria:

Patients (≥ 15 years old) with more than or equal to 2 following criteria:-

1)Untreated LDL cholesterol level of ≥ 180 mg/dL

-

2)Tendon xanthoma or xanthoma tuberosum

-

3)Family history of FH or premature CAD within second-degree relatives

Patients (< 15 years old) with all the following criteria:-

1)Untreated LDL cholesterol level of ≥ 140 mg/dL

-

2)Family history of FH or premature CAD within second-degree relatives

-

1)

-

Genetic diagnosis criteria:

Patients with heterozygous causative variant at the LDLR gene

Patients who meet both A and B criteria are defined as heterozygous FH.

Loss-of-function variants are determined as variants with either of the following criteria: 1) ClinVar pathogenic or likely pathogenic; 2) Multiple damaging score indicate damaging; or 3) Co-segregated with phenotype within the family of more than 4 members.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint is the changes of plasma RLP cholesterol levels after OFTT cream loading between sitosterolemia and heterozygous FH14, 15). We evaluate these changes by calculating area-under-thecurves between the groups. We measure them at baseline (before loading), and 2 hours, 4 hours, and 6 hours after loading. The secondary endpoints are the changes of following indices at baseline, 2 hours, 4 hours, and 6 hours after OFTT cream loading: plasma total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, LDL-C, non-HDL cholesterol, RLP triglyceride, sitosterol, lathosterol, campesterol, apolipoprotein A-I, apolipoprotein A-II, apolipoprotein-B (including B-48)23), apolipoprotein C-II, apolipoprotein C-III, and apolipoprotein E levels.

OFTT Cream Loading

All patients receive OFTT cream (50 g/body surface area square meter, orally only once)14, 15, 24) after a 12-hour overnight fast, either before the lipid-lowering treatment or after discontinuation of medication for at least 4 weeks. The cream includes 34% of fat, 74 mg of cholesterol (341 kcal/100 g), and is rich in palmitic [C16:0] and oleic [C18:1] acids.

Safety Monitoring

We check all unfavorable or unintended events/symptoms for patients as well as study investigators through this study period. It does not matter if the events are associated with this study or not.

In terms of OFTT cream, it may cause gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

Data Management

Patients' clinical data and blood samples are coded with study-specific identification number. RLP cholesterol and apolipoproteins are measured at a central clinical laboratory (SRL, Inc, Tokyo, Japan). Plasma concentrations of TC, TG, and HDL cholesterol are determined enzymatically. LDL-C level is calculated using the Friedewald equation25, 26) for those with triglycerides < 400 mg/dL. If triglycerides ≥ 400 mg/dL, plasma LDL-C level is directly measured (Sekisui Medical, Tokyo, Japan). We determine plasma sterol levels using gas–liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry27).

Sample Size

We recruit a total of 20 patients: 5 patients of homozygous sitosterolemia; 5 patients of heterozygous sitosterolemia; and 10 patients of heterozygous FH as controls. Since homozygous sitosterolemia is an extremely rare disease (1 in 1 million), it is impossible to recruit more subjects.

Statistical Analysis

We compare outcomes between the sitosterolemic group and FH group. For continuous variables, we use Mann–Whitney U test to compare continuous variables between two groups. We also use a linear regression if adjustments are needed.

Discussion and Conclusion

This is the first study to evaluate whether sitosterolemia patients have a higher post-prandial RLP cholesterol level compared to heterozygous FH patients.

In terms of mechanisms for higher cholesterol levels, FH patients have high LDL-C levels mainly because of losing function of LDL receptor at liver9). On the other hand, sitosterolemic patients have high LDL-C levels because of dysfunction of ABCG5/ABCG8 in intestine and biliary tract, that leads to inappropriate absorption and excretion of cholesterols1). These conditions indicate that unlike FH, cholesterol levels in sitosterolemic patients are sensitive to dietary cholesterols. Indeed, our previous study supported this idea—breast feeding, which contained high cholesterols and sterols, could cause very high LDL-C levels in patients with infantile sitosterolemia13). If they are truly vulnerable to dietary cholesterols, post-prandial RLP cholesterol levels of sitosterolemic patients should be increased after oral fat loading, compared to FH patients.

This hypothesis also points out that it might be possible for sitosterolemic patients to lower their cholesterol levels by fat-restricted diet. In addition, it may become an additional clinical evidence to cut off dietary cholesterols for patients with sitosterolemia to potentially prevent high plasma LDL-C and future atherosclerosis.

Disclosures

Akihiro Nomura has nothing to disclose. Hayato Tada has received research scholarship from Takeda Science Foundation, Mochida Memorial Foundation, Japan Research Promotion Society for Cardiovascular Diseases, Sanofi K.K, and Astellas Foundation for Research on Metabolic Disorders. Atsushi Nohara has received research scholarship from MSD K.K., Sanofi K.K., Shionogi&Co., Ltd., Kowa Co., Ltd., Astellas Pharma Inc., AstraZeneca K.K., Keiai-Kai Medical Corp., and Biopharm of Japan Co. Masa-aki Kawashiri has received honoraria from Amgen Astellas Biopharma K.K., Astellas Pharma Inc., and Sanofi K.K. Masakazu Yamagishi has received honoraria from Astellas Pharma Inc., Daiichi-Sankyo Co., Ltd., Shionogi&Co., Ltd., and Kowa Co., Ltd.

References

- 1). Berge KE, Tian H, Graf GA, Yu L, Grishin NV, Schultz J, Kwiterovich P, Shan B, Barnes R, Hobbs HH: Accumulation of dietary cholesterol in sitosterolemia caused by mutations in adjacent ABC transporters. Science, 2000; 290: 1771-1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Teupser D, Baber R, Ceglarek U, Scholz M, Illig T, Gieger C, Holdt LM, Leichtle A, Greiser KH, Huster D, Linsel-Nitschke P, Schafer A, Braund PS, Tiret L, Stark K, Raaz-Schrauder D, Fiedler GM, Wilfert W, Beutner F, Gielen S, Grosshennig A, Konig IR, Lichtner P, Heid IM, Kluttig A, El Mokhtari NE, Rubin D, Ekici AB, Reis A, Garlichs CD, Hall AS, Matthes G, Wittekind C, Hengstenberg C, Cambien F, Schreiber S, Werdan K, Meitinger T, Loeffler M, Samani NJ, Erdmann J, Wichmann HE, Schunkert H, Thiery J: Genetic regulation of serum phytosterol levels and risk of coronary artery disease. Circ Cardiovasc Genet, 2010; 3: 331-339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). Silbernagel G, Chapman MJ, Genser B, Kleber ME, Fauler G, Scharnagl H, Grammer TB, Boehm BO, Makela KM, Kahonen M, Carmena R, Rietzschel ER, Bruckert E, Deanfield JE, Miettinen TA, Raitakari OT, Lehtimaki T, Marz W: High intestinal cholesterol absorption is associated with cardiovascular disease and risk alleles in ABCG8 and ABO: evidence from the LURIC and YFS cohorts and from a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2013; 62: 291-299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Stender S, Frikke-Schmidt R, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjaerg-Hansen A: The ABCG5/8 cholesterol transporter and myocardial infarction versus gallstone disease. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2014; 63: 2121-2128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Tsubakio-Yamamoto K, Nishida M, Nakagawa-Toyama Y, Masuda D, Ohama T, Yamashita S: Current therapy for patients with sitosterolemia--effect of ezetimibe on plant sterol metabolism. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2010; 17: 891-900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Yoshida A, Naito M, Miyazaki K: Japanese sisters associated with pseudohomozygous familial hypercholesterolemia and sitosterolemia. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2000; 7: 33-38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Mabuchi H: Half a Century Tales of Familial Hypercholesterolemia (FH) in Japan. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2017; 24: 189-207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8). Watts GF, Ding PY, George P, Hagger MS, Hu M, Lin J, Khoo KL, Marais AD, Miida T, Nawawi HM, Pang J, Park JE, Gonzalez-Santos LB, Su TC, Truong TH, Santos RD, Soran H, Yamashita S, Tomlinson B, for the members of the “Ten countries S : Translational Research for Improving the Care of Familial Hypercholesterolemia: The “Ten Countries Study” and Beyond. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2016; 23: 891-900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Mabuchi H, Nohara A, Noguchi T, Kobayashi J, Kawashiri MA, Tada H, Nakanishi C, Mori M, Yamagishi M, Inazu A, Koizumi J, Hokuriku FHSG: Molecular genetic epidemiology of homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia in the Hokuriku district of Japan. Atherosclerosis, 2011; 214: 404-407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Tada H, Kawashiri MA, Yamagishi M: Clinical Perspectives of Genetic Analyses on Dyslipidemia and Coronary Artery Disease. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2017; 24: 452-461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Lee MH, Lu K, Hazard S, Yu H, Shulenin S, Hidaka H, Kojima H, Allikmets R, Sakuma N, Pegoraro R, Srivastava AK, Salen G, Dean M, Patel SB: Identification of a gene, ABCG5, important in the regulation of dietary cholesterol absorption. Nat Genet, 2001; 27: 79-83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). Tada H, Kawashiri MA, Okada H, Endo S, Toyoshima Y, Konno T, Nohara A, Inazu A, Takao A, Mabuchi H, Yamagishi M, Hayashi K: A Rare Coincidence of Sitosterolemia and Familial Mediterranean Fever Identified by Whole Exome Sequencing. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2016; 23: 884-890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Tada H, Kawashiri MA, Takata M, Matsunami K, Imamura A, Matsuyama M, Sawada H, Nunoi H, Konno T, Hayashi K, Nohara A, Inazu A, Kobayashi J, Mabuchi H, Yamagishi M: Infantile Cases of Sitosterolaemia with Novel Mutations in the ABCG5 Gene: Extreme Hypercholesterolaemia is Exacerbated by Breastfeeding. JIMD Rep, 2015; 21: 115-122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14). Inazu A, Nakajima K, Nakano T, Niimi M, Kawashiri MA, Nohara A, Kobayashi J, Mabuchi H: Decreased post-prandial triglyceride response and diminished remnant lipoprotein formation in cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) deficiency. Atherosclerosis, 2008; 196: 953-957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15). Tada H, Kawashiri MA, Tanaka A, Nakano T, Nakajima K, Inoue T, Noguchi T, Nakanishi C, Konno T, Hayashi K, Nohara A, Inazu A, Kobayashi J, Mabuchi H, Yamagishi M: Post-prandial remnant lipoprotein metabolism in autosomal recessive hypercholesterolaemia. Eur J Clin Invest, 2012; 42: 1094-1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16). Karpe F, Boquist S, Tang R, Bond GM, de Faire U, Hamsten A: Remnant lipoproteins are related to intima-media thickness of the carotid artery independently of LDL cholesterol and plasma triglycerides. J Lipid Res, 2001; 42: 17-21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17). Kugiyama K, Doi H, Motoyama T, Soejima H, Misumi K, Kawano H, Nakagawa O, Yoshimura M, Ogawa H, Matsumura T, Sugiyama S, Nakano T, Nakajima K, Yasue H: Association of remnant lipoprotein levels with impairment of endothelium-dependent vasomotor function in human coronary arteries. Circulation, 1998; 97: 2519-2526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). McNamara JR, Shah PK, Nakajima K, Cupples LA, Wilson PW, Ordovas JM, Schaefer EJ: Remnant-like particle (RLP) cholesterol is an independent cardiovascular disease risk factor in women: results from the Framingham Heart Study. Atherosclerosis, 2001; 154: 229-236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19). Escola-Gil JC, Quesada H, Julve J, Martin-Campos JM, Cedo L, Blanco-Vaca F: Sitosterolemia: diagnosis, investigation, and management. Curr Atheroscler Rep, 2014; 16: 424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20). Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. Sitosterolemia. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-10900000-Kenkoukyoku/0000101127.pdf (Last accessed, Jan 31, 2017).

- 21). Teramoto T, Sasaki J, Ishibashi S, Birou S, Daida H, Dohi S, Egusa G, Hiro T, Hirobe K, Iida M, Kihara S, Kinoshita M, Maruyama C, Ohta T, Okamura T, Yamashita S, Yokode M, Yokote K, Harada-Shiba M, Arai H, Bujo H, Nohara A, Ohta T, Oikawa S, Okada T, Wakatsuki A: Familial hypercholesterolemia. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2014; 21: 6-10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22). Japan Atherosclerosis Society (JAS) Guidelines for Prevention of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Diseases. 2017; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23). Masuda D, Sakai N, Sugimoto T, Kitazume-Taneike R, Yamashita T, Kawase R, Nakaoka H, Inagaki M, Nakatani K, Yuasa-Kawase M, Tsubakio-Yamamoto K, Ohama T, Nakagawa-Toyama Y, Nishida M, Ishigami M, Masuda Y, Matsuyama A, Komuro I, Yamashita S: Fasting serum apolipoprotein B-48 can be a marker of postprandial hyperlipidemia. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2011; 18: 1062-1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24). Nabeno-Kaeriyama Y, Fukuchi Y, Hayashi S, Kimura T, Tanaka A, Naito M: Delayed postprandial metabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in obese young men compared to lean young men. Clin Chim Acta, 2010; 411: 1694-1699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25). Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS: Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clinical chemistry, 1972; 18: 499-502 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26). Warnick GR, Knopp RH, Fitzpatrick V, Branson L: Estimating low-density lipoprotein cholesterol by the Friedewald equation is adequate for classifying patients on the basis of nationally recommended cutpoints. Clinical chemistry, 1990; 36: 15-19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27). Ahmida HS, Bertucci P, Franzo L, Massoud R, Cortese C, Lala A, Federici G: Simultaneous determination of plasmatic phytosterols and cholesterol precursors using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) with selective ion monitoring (SIM). J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci, 2006; 842: 43-47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]