Abstract

Density functional theory calculations have been performed to study the detailed mechanism of Ni-mediated [3+2] cycloaddition of 2-trifluoromethyl-1-alkenes with alkynes via cleavage of two C-F bonds. It was found that the reaction pathway involves oxidative cyclization, the first β-fluorine elimination, and then intramolecular 5-endo insertion of difluoroalkene, followed by the second cleavage of C-F bond, and finally the dissociation of difluorides yields the fluorine-containing product cyclopentadienes in sequence. The overall rate-determining step is the combined processes of the β-fluorine elimination and the 5-endo insertion. Furthermore, we investigated the effect of different ligands and the regioselectivity of asymmetric alkynes. The detailed energy profiles and structures are presented in this study.

Keywords: DFT studies, Ni-mediated, C-F cleavage, cyclopentadiene derivative, regioselectivity

Introduction

The knowledge of formation and breakage of C–C bonds is important issue in the organic synthesis reactions. However, the high strength of the C–C bond makes it difficult to achieve. Weaker metal–carbon (M–C) bonding provides the necessary fundamental basis for catalytic transformations (Macgregor et al., 2003; Ananikov et al., 2005; Ananikov, 2015). Nickel holds a special place among the transition metals on account of reactivity trends, functional group tolerance, and catalytic activity (Montgomery, 2004). Theoretical studies showed that the M–C bond strength of group 10 metals changes in the order Ni–C < Pd–C < Pt–C < C–C (Macgregor et al., 2003; Ananikov et al., 2005; Ananikov, 2015), which supports the higher reactivity of nickel species and provides a reference for the design of active catalysts. In particular, Ni-catalyzed cross-coupling of electrophiles (organic halides and pseudohalides) with carbon nucleophiles (organometallic compounds) have important consequences (Negishi, 1982; Tamao et al., 1982; Kumada, 2009). The chemical inertness of the C–F bond makes the chemistry of C–F bond activation a specialized field. Fluorine forms the strongest σ bond to carbon and its high electronegativity leads to a significant ionic bond character. Likewise, fluorine substituents are weak Lewis bases and fluoride is a poor leaving group, which all give rise to a high thermodynamic stability and a kinetic inertness of C–F bonds (Kuehnel et al., 2013).

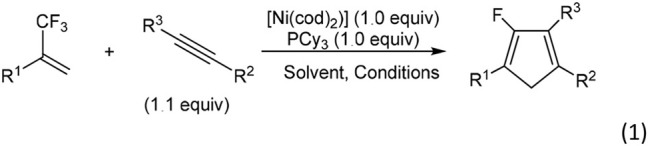

Outstanding progress has been made recently in transition-metal-mediated C–F activation reactions and in the development of new catalytic processes for the functionalization of fluoroorganics (Murphy et al., 1997; Jones, 2003; Mazurek and Schwarz, 2003; Ahrens et al., 2015). Research on transition metal-catalyzed C (sp2)–F bond activation has been intensively studied (Amii and Uneyama, 2009; Braun et al., 2009; Laot et al., 2010; Ohashi et al., 2011; Lv et al., 2012; Fujita et al., 2016) while C(sp3)–F bond activation needs much more exploration (Choi et al., 2011; Benedetto et al., 2012; Blessley et al., 2012; Kuehnel et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2015; Huang and Hayashi, 2016). Recently, Prof. Ichikawa's group (Ichitsuka et al., 2014) developed an efficient synthesis of 2-fluoro-1,3-cyclopentadienes through 2-trifluoromethyl-1-alkenes with alkynes by sequential β-fluorine elimination of a trifluoromethyl group (Equation 1).

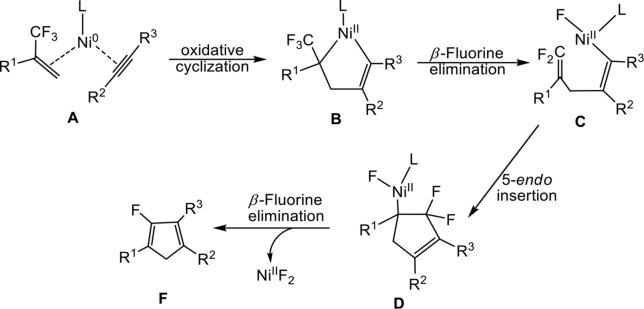

To account for the reactions, the authors proposed a plausible reaction pathway on the basis of the experimental observations (Scheme 1). In the proposed mechanism, nickelacyclopentene B bearing a trifluoromethyl group was formed by oxidative cyclization of 2- trifluoromethyl-1-alkene and alkyne with Ni0L reactant. Subsequently, β-fluorine elimination involving one of C–F bond of trifluoromethyl in organonickel B then generates the intermediate C, followed by intramolecular 5-endo insertion of difluoroalkene leading to the formation of difluorocyclopentenylnickel D. Finally, in D, the second β-fluorine elimination of NiIIF2 yields the product 2-fluoro-1, 3-cyclopentadienes.

Scheme 1.

A plausible mechanism proposed on the basis of the experimental observations.

In this article, we plan to elucidate the detailed mechanism of the nickel-mediated [3+2] cycloaddition reaction shown in Equation (1) and explore the sequential β-fluorine elimination and the normally disfavored insertion in C via density functional theory (DFT) calculations. Moreover, we are interested in another different addition method from A to B, involving the alkyne insertion process. Depending on the calculations we obtained, we discuss the regio-selectivity of asymmetric alkynes.

Computational details

The geometries of all reported reactants, intermediates, transition states, and products were optimized at the DFT level using the B3LYP hybrid functional (Lee et al., 1988; Miehlich et al., 1989; Becke, 1993; Stephens et al., 1994). All of the Ni and P atoms in this analysis were described using the LanL2DZ basis set, including a double-ζ valence basis set with the effective core potentials (ECPs) of Hay and Wadt (1985a,b; Wadt and Hay, 1985). Polarization functions were added for Ni (ζf = 3.130) and P (ζd = 0.340) (Huzinaga, 1985; Ehlers et al., 1993; Höllwarth et al., 1993). The 6-31G(d) basis set was used for other atoms (Hariharan and Pople, 1973; Koseki et al., 1992). Vibrational frequency calculations were carried out at the same level to confirm the nature of all of the optimized structures as the minima (zero imaginary frequency) or transition states (one imaginary frequency). Each of the calculated transition states connects two relevant minima were further confirmed by intrinsic reaction coordinates (IRC) calculations (Fukui, 1970, 1981). In consideration of the dispersion and solvation effects, single-point energy calculations (based on the gas-phase optimized geometries) were performed at the M06 (Truhlar, 2008; Zhao and Truhlar, 2008a,b, 2009) level of theory in conjunction with the solvation model density (SMD) continuum method (Marenich et al., 2009). According to the reaction conditions, 1,4-dioxane was employed as the solvent in the SMD calculations. All the single-point calculations employ a larger basis set SDD for Ni and 6-311++G(d,p) for other atoms, respectively, except P atom remains unchanged. In this paper, the dispersion- and solvation-corrected free energies are used for discussion throughout the text. All calculations were performed using the Gaussian 09 software package (Frisch et al., 2009). And the selected calculated structures were visualized using the XYZviewer software (de Marothy, 2010). Cartesian coordinates and total energies for all of the calculated structures are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Results and discussion

Mechanisms of the NI-mediated reaction shown in scheme 1

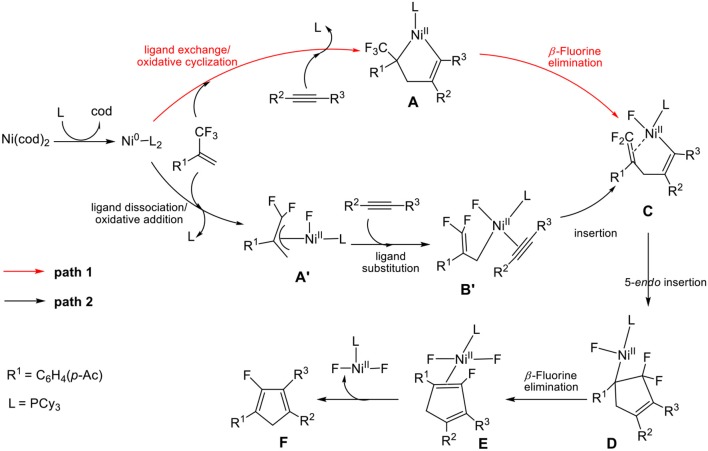

In the nickel-mediated cycloaddition reaction, we expanded two possible oxidative addition methods in Scheme 2 to better clarify the detailed reaction mechanism in Equation (1). Path 1 starts from ligand exchange and oxidative cyclization of fluorine-containing alkenes and alkynes with Ni0 in complex A, which affords a five-membered nickelacycle B, followed by β-fluorine elimination gives C. However, path 2 proceeds with ligand dissociation and oxidative addition of the C-F bond in 2-trifluoromethyl-1-alkenes, which results in the formation of the conjugated species A′, followed by the ligand substitution gives B′. Then, the insertion of alkynes leads to the formation of species C. C is the common species for both path 1 and path 2. In the following step, the intramolecular 5-endo insertion generates a new five-membered difluoro-cyclopentadiene D. β-fluorine elimination of D affords the Ni(II) species, from which leaving of the NiF2Ln, provides the monofluorinated cyclopentadiene product.

Scheme 2.

Two different oxidative addition pathways for the Ni-mediated reaction.

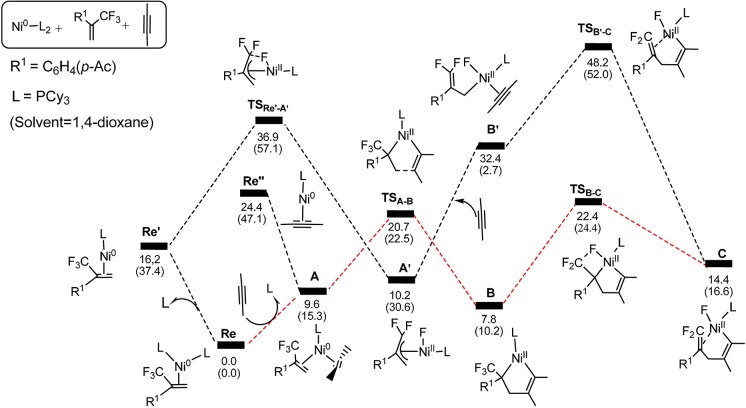

On the basis of the mechanism shown in Scheme 2, we select butyne as simple substitute for symmetrical experimental model substrates 4-octyne and employ PCy3 as ligand in our calculations. The calculated energy profiles are presented in the Figures 1, 3, and the selected optimized structures of intermediates and transition states are depicted in Figures 2, 4.

Figure 1.

Energy profiles calculated for the oxidative cyclization (TSA−B) and β-Fluorine elimination (TSB−C) (path 1 in red line), oxidative addition (TS), ligand substitution (A′ → B′) and alkyne insertion (TS) (path 2 in black line). The solvation-corrected relative free energies and electronic energies (in parentheses) are given in kcal/mol.

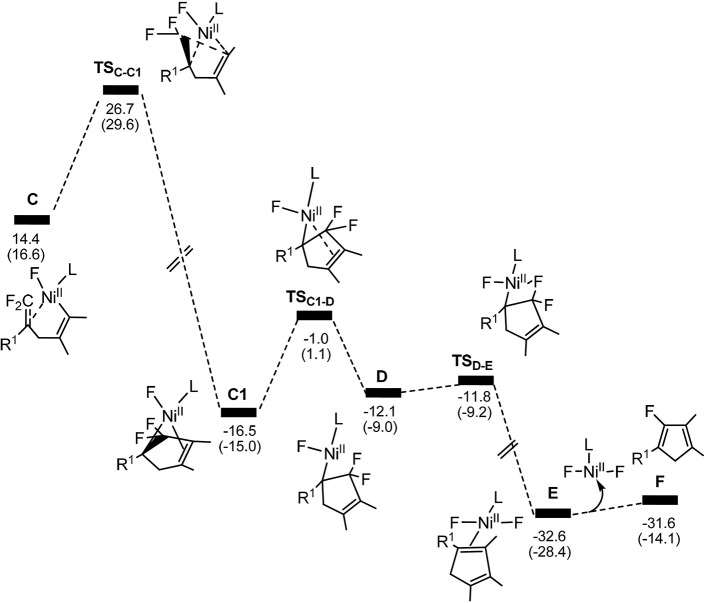

Figure 3.

Calculated energy profiles for the pathway starting from complex C to the product. The solvation-corrected relative free energies and electronic energies (in parentheses) are given in kcal/mol.

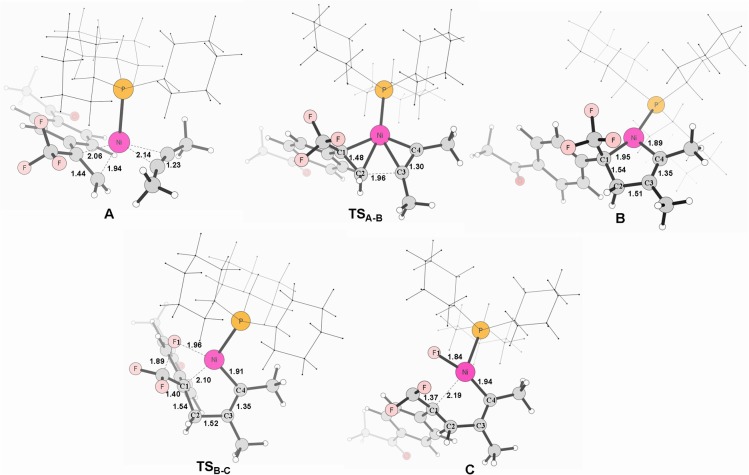

Figure 2.

Structures calculated for selected intermediates and TSs in the oxidative cyclization (TSA−B) and β-fluorine elimination (TSB−C) (path 1 in red line). The distances are given in angstroms (Å).

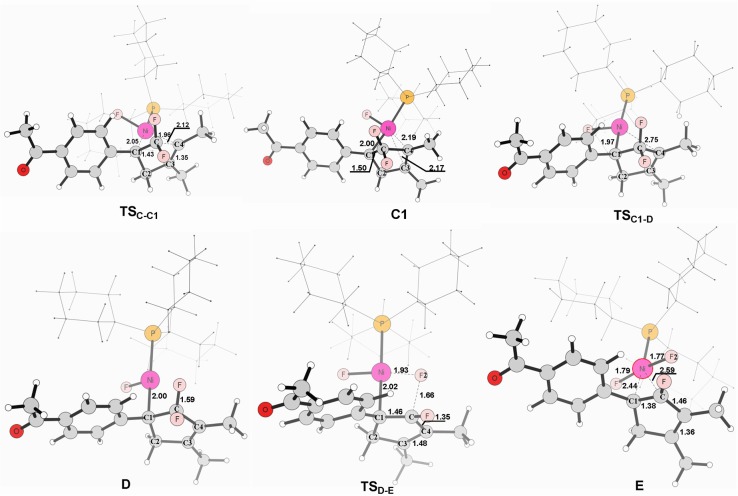

Figure 4.

Structures calculated for selected intermediates and TSs for complex C to product. The distances are given in angstroms (Å).

Firstly, we focus on the two different oxidative addition mechanisms shown in Figure 1. Ni(0) establishes initial contact with alkene through the way of π-coordination and two PCy3 ligands, resulting in a stable three-component complex Re, which is lower in energy than the two-component complexes, Re′ and Re′′, by 16.2 and 24.4 kcal/mol, respectively. For path 1(in red line), ligand exchange of complex Re with one PCy3 ligand to form another three-component complex A, which is found to be 9.6 kcal/mol higher than Re in free energy. A undergoes oxidative addition to form the metallacycle intermediate B via the transition state TSA−B with a barrier of 11.1 kcal/mol. TSA−B has C1-C2, C2-C3, and C3-C4 distances of 1.48, 1.96, and 1.30 Å, respectively (Figure 2). In B, both C = C of alkene and C ≡ C of alkyne were elongated to 1.54 and 1.35 Å, respectively. Subsequently, the first β-fluorine elimination reaction occurs from complex B in path 1 to C through the transition state TSB−C, in which the migration of F1 atom from CF3 to Ni(II) center via the cleavage of the C–F bond and C–Ni bond and the formation of Ni–F bond simultaneously with a barrier of 14.6 kcal/mol. The cleavage of C–F1, Ni–C1 and formation of Ni–F1 bond occur synchronously, and the C–F1, Ni-F1 and Ni–C1 distances being 1.89, 1.96, and 2.10 Å, respectively, as shown in Figure 2. From Figure 1, we can see that β-fluorine elimination is the most energy-demanding for the conversion from Re to C. The overall barrier calculated for Re to C is 22.4 kcal/mol (Re → TSB−C).

For path 2 (in black line), the reaction starts with Re′, followed by the oxidative addition of the C-F bond to Ni(0) via the transition state TSRe'-A', generating the corresponding π-allylnickel complex A′ with a barrier of 20.7 kcal/mol. The coordination of the alkyne CH3C=CCH3 gives the precursor intermediate B′ ready for alkyne insertion. Alkyne insertion leads to formation of C, having an approximate ring structure with the Ni metal center being coordinated with the alkenyl moiety, via a very high barrier transition state (38.0 kcal/mol, Figure 1). The C1–C(F2) distance is shorten to 1.37 Å (Figure 2). The alkyne insertion is the most energy-demanding for the conversion from Re′ to C. The overall barrier calculated for Re′ to C is 38.0 kcal/mol (A′ → TSB'-C). It is worth of note that the pathway involving the alkyne insertion path 2, have considerably higher barrier than the path1 (Figure 1).

From complex C, both path 1 and path 2 would undergo the same reaction process 5-endo insertion through transition state TSC−C1, shown in Figure 3, a disfavored process for the construction of five-membered rings in general because of the severe distortions required in the reaction geometry (Sakoda et al., 2005; Ichikawa et al., 2006). However, complex C possesses an unique moiety of 1,1-difluoro-1-alkenes, making even a nucleophilic 5-endo-trig approach feasible. The polarization of the C = C bond caused by the two fluorines (Chambers, 1973; Banks et al., 1994; Sakoda et al., 2005; Fujita et al., 2014) results in electrostatic attraction for an intramolecular nucleophile to overcome the difficulty of the formation of ring complex precursor C1 with a barrier of 12.4 kcal/mol (Figure 3). The distance of C(F2)–C4 is close to 2.12 Å (Figure 4). Then, C1 isomerizes to the difluorocyclopentenylnickelD by breaking the Ni center and C = C bond with a barrier of 15.5 kcal/mol. In D, the Ni metal center has no interaction with C3 atom, as indicated by the long Ni–C(F2) and Ni–C3 distances of 2.49 and 3.27 Å, respectively. Whereafter, β-fluorine elimination in D forming the 5-endo-trig species E via the transition state TSD−E only need to overcome an energy barrier of 0.3 kcal/mol. In this transition state, cleavage of C–F2 and re-bonding of Ni–F2 occur synchronously with the distances being 1.66 and 1.93 Å, respectively. The distance of Ni–F2 decreases to 1.77 Å in complex E. Finally, the dissociation of difluorides would yield the desired 2-fluoro-1,3-cyclopentadienes product.

On the basis of the calculations shown in Figures 1, 3, it is notable that the pathway involving alkyne insertion (path 2 in Figure 1) has considerably higher barriers than that involving oxidative cyclization (path 1 in Figure 1). And the 5-endo insertion transition state is rate-determining for the whole Ni-mediated reaction and the overall energy barrier is calculated to be 26.7 kcal/mol, corresponding to the energy difference between TSC−C1 and complex Re (Figures 1, 3). The first β-fluorine elimination process is endergonic. Therefore, the combined processes of the β-fluorine elimination and the 5-endo insertion can be viewed as the rate-determining step because the endergonicity of the β-fluorine elimination process contributes to the overall rate-determining barrier. This finding is consistent with the recent DFT study by Bi's group (Zhang et al., 2017), in which the 5-endo insertion transition state is also the rate-determining for the whole Ni-mediated reaction.

Effect of ligand

Based on the detailed mechanistic discussion above, we have achieved an understanding of the competition between two alternative pathways. Next, we turn our attention to investigate why the less electron-donating group is ineffective for the reactions. Experimentally, reactions carried out in the presence of PPh3 or 1,10-phenanthroline resulting in no expected cyclization products. It was also found that when the reaction was carried out in strong electron-donating ligands, IMes or PCy3, the yield was unexpectedly improved. In order to understand the effect of the ligands on the reaction outcomes, we calculated the energy profiles for the path 1 (from the reactants to 5-endo insertion process) by selecting 1,10-phenanthroline as the ligand (Figure 5).

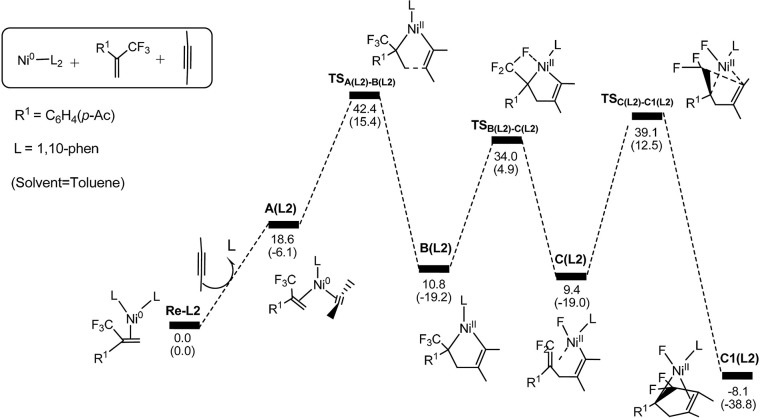

Figure 5.

Energy profiles calculated for the path 1 by using 1,10-phenanthroline as the ligand. The solvation-corrected relative free energies and electronic energies (in parentheses) are given in kcal/mol.

In Figure 5, we can clearly see that the oxidative cyclization transition state is the rate-determining from Re-L2 to C1(L2) reaction and the overall barrier is calculated to be 42.4 kcal/mol, implying the oxidative cyclization process is infeasible under ambient conditions. This result is consistent with the experimental observation that electron-withdrawing ligand do not promote the reactions. The reason is that the oxidation reaction occurs easily on the highly electron-rich Ni(0) species derived from strong electron-donating ligands.

Regioselectivity

In this section, we examine the origin for the regioselectivity observed for the reactions of unsymmetrical alkynes. When asymmetric alkynes (in Equation 1) are used, formation of regioisomeric products is highly possible. Experimentally, for the [3+2] cycloaddition of 2-trifluoromethyl-1-alkenes with asymmetric alkynes, the resulting products give complete regioselectivity with the R3-substituent carbon coupling with the fluorine-bonded carbon (Ichitsuka et al., 2014). For example, 4-methyl-2-pentyne (MeC ≡ Ci-Pr) and 1-phenyl-1-propyne (MeC ≡ CPh) were employed to illustrate the regio-selectivity for the cycloaddition reaction. When 4-methyl-2-pentyne was used as the alkyne substrate, the difluoro carbon atom preferred to couple with the methyl-substituted carbon. While the alkyne 1-phenyl-1-propyne preferred to couple with the phenyl-substituted carbon rather than methyl-substituted carbon.

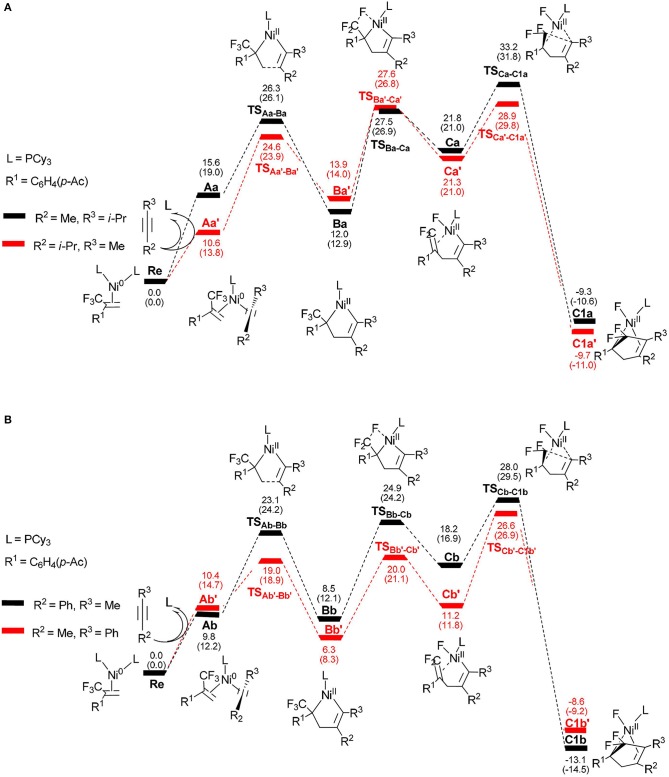

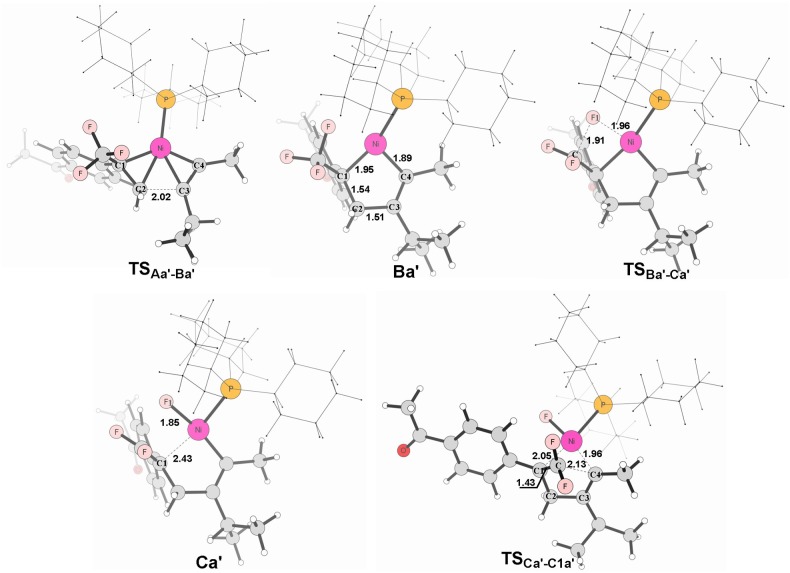

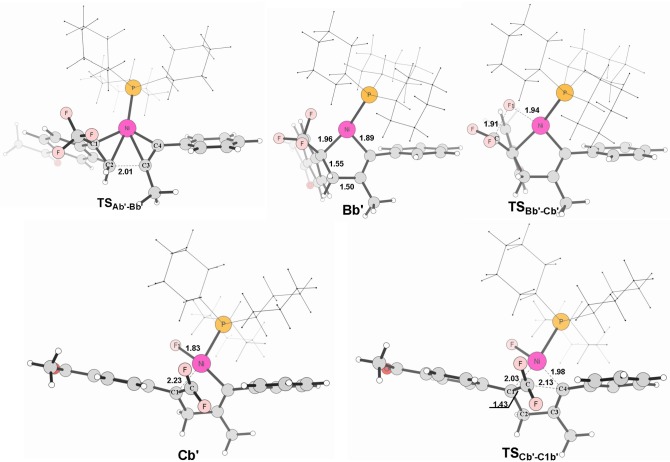

To better understand the regioselectivity observed, we calculated the energy profiles for the reaction shown in Figure 6. The calculated molecular structures for selected intermediates and transition states are also presented in Figures 7, 8. On the basis of the proposed mechanism shown in Scheme 2, the regioselectivity was initially controlled by the oxidative coupling step and it is obvious that the most favorable pathway is following the red line for 4-methyl-2-pentyne (Figure 6A) and 1-phenyl-1-propyne (Figure 6B). The overall barriers for the more favorable cycloaddition pathway were calculated to be 28.9 kcal/mol (Re → TS, Figure 6A) and 26.6 kcal/mol (Re → TS, Figure 6B), respectively. The calculation results are consistent with the experimentally observed regioselectivity (Ichitsuka et al., 2014).

Figure 6.

Energy profiles calculated for the reactions of unsymmetrical alkynes, 4-methyl-2-pentyne (A) and 1-phenyl-1-propyne (B), to complexes C1a/C1a′ and C1b/C1b′, respectively. The solvation-corrected relative free energies and electronic energies (in parentheses) are given in kcal/mol.

Figure 7.

Structures calculated for selected intermediates and TSs for path in Figure 6A. The distances are given in angstroms (Å).

Figure 8.

Structures calculated for selected intermediates and TSs for path in Figure 6B. The distances are given in angstroms (Å).

It is well-known that the oxidation state of metal nickel changes from 0 to +2 through TSAa−Ba/TS and TSAb−Bb/TS, in which the coordinated alkyne acts as a nucleophile and favorably attacks metal center. The alkyne 4-methyl-2-pentyne bears two electron-donating groups methyl and isopropyl, by contrast, i-Pr plays a larger role. It makes the methyl-substituted carbon of MeC ≡ Ci-Pr π electron richer in comparison with the i-Pr-substituted carbon, facilitating both the oxidative addition and electrostatic attraction between the –CF2 carbon and the internal nucleophile. As a result, the desired pathway (red line in Figure 6A) is both electronically and sterically favorable for alkyne 4-methyl-2-pentyne by oxidative cycloaddition. The energy barrier of the cycloaddition is 14.0 kcal/mol through the transition state TS, in which the C1–C2 distance is 2.02 Å and the i-Pr substituent is far away from the metal-bonded ligands (Figure 7). 5-endo insertion of Ca′ to form C1a′ via the transition state TSis required to overcome an energy barrier of only 7.6 kcal/mol because of the electrostatic attraction. The distance of C(F2)–C4 in TSis 2.13 Å (Figure 7).

When used the alkyne 1-phenyl-1-propyne, the electron-accepting phenyl makes the Me-substituted carbon of MeC ≡ CPh π electron poorer in comparison with the Ph-substituted carbon. Therefore, the nickel center is inclined to coupling with the Ph-substituted carbon no matter for oxidative cyclization or for electrostatic attraction, with the energy barriers of 8.6 kcal/mol and 15.4 kcal/mol, respectively (red line Figure 6B). The distances of C1–C2 in TSAb'-Bb' and C(F2)–C4 in TSCb'-C1b' are 2.01 and 2.13 Å, respectively, shown in Figure 8.

Conclusions

The detailed reaction mechanism for Ni-mediated [3+2] cycloaddition of 2-trifluoromethyl-1-alkenes with alkynes leading to formation of cyclopentadiene derivatives have been studied with the aid of DFT calculations. For the energetics associated with the reaction, two possible oxidative additions were investigated in detail. Path 1 starts from ligand exchange of complex Re to form A. Then, the oxidative cyclization of fluorine-containing alkenes and alkynes with Ni0 in complex A, which affords a five-membered nickelacycle B, followed by β-Fluorine elimination gives C. However, path 2 proceeds with oxidative addition of the C-F bond in 2-trifluoromethyl-1-alkenes, which results in the formation of the conjugated species A′, followed by the ligand substitution gives B′. Then, the insertion of alkynes leads to the formation of species C. C is the common species for both path 1 and path 2. In the following step, the intramolecular 5-endo insertion generates a new five-membered difluoro-cyclopentadiene D. β-Fluorine elimination of D affords the Ni(II) species, from which leaving of the NiF2Ln, provides the monofluorinated cyclopentadiene product. The pathway involving the alkyne insertion path 2 have considerably higher barrier than the path1. The combined processes of the β-fluorine elimination and the 5-endo insertion can be viewed as the rate-determining step according to the calculation results. The overall free energy barrier for the whole reaction was computed to be 26.7 kcal/mol (Re → TSC−C1).

The regioselectivity was also investigated using the unsymmetric alkynes 4-methyl-2-pentyne (MeC ≡ Ci-Pr) and 1-phenyl-1-propyne (MeC ≡ CPh) as the substrate molecules. The alkyne MeC ≡ Ci-Pr bears two electron-donating groups methyl and isopropyl, by contrast, i-Pr plays a larger role. It makes the methyl-substituted carbon of MeC ≡ Ci-Pr π electron richer in comparison with the i-Pr-substituted carbon, facilitating both the oxidative cyclization and electrostatic attraction between the –CF2 carbon and the internal nucleophile. When used the alkyne MeC ≡ CPh, the electron-accepting phenyl makes the Me-substituted carbon of MeC ≡ CPh π electron poorer in comparison with the Ph-substituted carbon. Therefore, the nickel center is inclined to coupling with the Ph-substituted carbon no matter for oxidative cyclization or for electrostatic attraction, eventually leading to formation of the experimentally observed regioisomer.

Author contributions

The work cannot be completed without kind cooperation of all authors. W-JC, BW, and XH were responsible for the study of concept and design of the project. R-NX and WL were responsible for the searching intermediates and transition states, analysis of data and drawing energy profiles. W-JC, XS, and Q-HW drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to its final form and gave final approval for its publication.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge supports from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 21603117), the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province of China (Grant No. 2017J01591), the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in Fujian Province University, and the College Students Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Plan Project of Quanzhou Normal University (201710399108).

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material, including Cartesian coordinates and total energies for all of the calculated structures, can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2018.00319/full#supplementary-material

References

- Ahrens T., Kohlmann J., Ahrens M., Braun T. (2015). Functionalization of fluorinated molecules by transition-metal-mediated C–F bond activation to access fluorinated building blocks. Chem. Rev. 115, 931–972. 10.1021/cr500257c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amii H., Uneyama K. (2009). C-F bond activation in organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 109, 2119–2183. 10.1021/cr800388c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananikov V. P. (2015). Nickel: the “spirited horse” of transition metal catalysis. ACS Catal. 5, 1964–1971. 10.1021/acscatal.5b00072 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ananikov V. P., Musaev D. G., Morokuma K. (2005). Theoretical insight into the C–C coupling reactions of the vinyl, phenyl, ethynyl, and methyl complexes of palladium and platinum. Organometallics 24, 715–723. 10.1021/om0490841 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banks R. E., Smart B. E., Tatlow J. C. (1994). Organofluorine Chemistry: Principles and Commercial Applications. New York, NY: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D. (1993). Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 5648 10.1063/1.464913 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetto E., Keita M., Tredwell M., Hollingworth C., Brown J., Gouverneur V. (2012). Platinum-catalyzed substitution of allylic fluorides. Organometallics 31, 1408–1416. 10.1021/om201029m [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blessley G., Holden P., Walker M., Brown J. M., Gouverneur V. (2012). Palladium-catalyzed substitution and cross-coupling of benzylic fluorides. Org. Lett. 14, 2754–2757. 10.1021/ol300977f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun T., Salomon M. A., Altenhöner K., Teltewskoi M., Hinze S. (2009). C-F activation at Rhodium boryl complexes: formation of 2-fluoroalkyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolanes by catalytic functionalization of hexafluoropropene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 1818–1822. 10.1002/anie.200805041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R. D. (1973). Fluorine in Organic Chemistry. New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Choi J., Wang D. Y., Kundu S., Choliy Y., Emge T. J., Krogh-Jespersen K., et al. (2011). Net oxidative addition of C(sp3)–F bonds to iridium via initial C–H bond activation. Science 332, 1545–1548. 10.1126/science.1200514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Marothy S. A. (2010). XYZViewer version 0.97. Stockholm. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A. W., Böhme M., Dapprich S., Gobbi A., Höllwarth A., Jonas V., et al. (1993). A set of f-polarization functions for pseudo-potential basis sets of the transition metals Sc-Cu, Y-Ag and La-Au. Chem. Phys. Lett. 208, 111–114. 10.1016/0009-2614(93)80086-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J., Trucks G. W., Schlegel H. B., Scuseria G. E., Robb M. A., Cheeseman J. R., et al. (2009). Gaussian 09, revision D.01. Pittsburgh, PA: Gaussian, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita T., Ikeda M., Hattori M., Sakoda K., Ichikawa J. (2014). Napuercleophilic 5-endo-trig cyclization of 3,3-difluoroallylic metal enolates and enamides: facile synthesis of ring-fluorinated dihydroheteroles. Synthesis 46, 1493–1505. 10.1055/s-0033-1340857 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita T, Watabe Y., Yamashita S., Tanabe H., Nojima T., Ichikawa J. (2016). Silver-catalyzed vinylic C–F bond activation: synthesis of 2-fluoroindoles from β,β-difluoro-o-sulfonamidostyrenes. Chem. Lett. 45, 964–966. 10.1246/cl.160427 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui F. (1981). The path of chemical reactions—the IRC approach. Acc. Chem. Res. 14, 363–368. 10.1021/ar00072a001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui K. (1970). A formulation of the reaction coordinate. J. Phys. Chem. 74, 4161–4163. 10.1021/j100717a029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan P. C., Pople J. A. (1973). The influence of polarization functions on molecular orbital hydrogenation energies. Theor. Chim. Acta 28, 213–222. 10.1007/BF00533485 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hay P. J., Wadt W. R. (1985a). Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for the transition metal atoms scandium to mercury. J. Chem. Phys. 82, 270–283. 10.1063/1.448799 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- xbib20Hay P. J., Wadt W. R. (1985b). Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for K to Au including the outermost core orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 82, 299–310. 10.1063/1.448975 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Höllwarth A., Böhme M., Dapprich S., Ehlers A. W., Gobbi A., Jonas V., et al. (1993). A set of d-polarization functions for pseudo-potential basis sets of the main group elements Al-Bi and f-type polarization functions for Zn, Cd, Hg. Chem. Phys. Lett. 208, 237–240. 10.1016/0009-2614(93)89068-S [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Hayashi T. (2016). Rhodium-catalyzed asymmetric arylation/defluorination of 1-(trifluoromethyl)alkenes forming enantioenriched 1,1-difluoroalkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 12340–12343. 10.1021/jacs.6b07844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huzinaga S. (1985). Basis sets for molecular calculations. Comp. Phys. Rep. 2, 281–339. 10.1016/0167-7977(85)90003-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa J., Sakoda K., Mihara K., Ito N. (2006). Heck-Type 5-endo-trig cyclizations promoted by vinylic fluorines: ring-fluorinated indene and 3H-pyrrole syntheses from 1,1-difluoro-1-alkenes. J. Fluorine Chem. 127, 489–504. 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2005.12.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ichitsuka T., Fujita T., Arita T., Ichikawa J. (2014). Double C-F bond activation through β-fluorine elimination: nickel-mediated [3+2] cycloaddition of 2-trifluoromethyl-1-alkenes with alkynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 7564–7568. 10.1002/anie.201405100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones W. D. (2003). Activation of C–F bonds using Cp*2ZrH2: a diversity of mechanisms. Dalton Trans. 35, 3991–3995. 10.1039/B307232K [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koseki S., Schmidt M. W., Gordon M. S. (1992). MCSCF/6-31G(d,p) calculations of one-electron spin-orbit coupling constants in diatomic molecules. J. Phys. Chem. 92, 10768–10772. 10.1021/j100205a033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehnel M. F., Holstein P., Kliche M., Krüger J., Matthies S., Nitsch D., et al. (2012). Titanium-catalyzed vinylic and allylic C-F bond activation-scope, limitations and mechanistic insight. Chem. Eur. J. 18, 10701–10714. 10.1002/chem.201201125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehnel M. F., Lentz D., Braun T. (2013). Synthesis of fluorinated building blocks by transition-metal-mediated hydrodefluorination reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 3328–3348. 10.1002/anie.201205260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumada M. (2009). Nickel and palladium complex catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of organometallic reagents with organic halides. Pure Appl. Chem. 52, 669–679. 10.1351/pac198052030669 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laot Y., Petit L., Zard S. Z. (2010). Synthesis of fluoroazaindolines by an uncommon radical ipso substitution of a carbon-fluorine bond. Org. Lett. 12, 3426–3429. 10.1021/ol101240f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C., Yang W., Parr R. G. (1988). Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 37, 785–789. 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv H., Zhan J. H., Cai Y. B., Yu Y., Wang B., Zhang J. L. (2012). π-π interaction assisted hydrodefluorination of perfluoroarenes by gold hydride: a case of synergistic effect on C-F bond activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 16216–16227. 10.1021/ja305204y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macgregor S. A., Neave G. W., Smith C. (2003). Theoretical studies on C-heteroatom bond formation via reductive elimination from group 10 M(PH3)2(CH3)(X) species (X = CH3, NH2, OH, SH) and the determination of metal-X bond strengths using density functional theory. Faraday Discuss. 124, 111–127. 10.1039/B212309F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marenich A. V., Cramer C. J., Truhlar D. G. (2009). Universal solvation model based on solute electron density and on a continuum model of the solvent defined by the bulk dielectric constant and atomic surface tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 6378–6396. 10.1021/jp810292n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek U., Schwarz H. (2003). Carbon-fluorine bond activation–looking at and learning from unsolvated systems. Chem. Commun. 34, 1321–1326. 10.1039/B211850E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miehlich B., Savin A., Stoll H., Preuss H. (1989). Results obtained with the correlation energy density functionals of becke and Lee, Yang and Parr. Chem. Phys. Lett. 157, 200–206. 10.1016/0009-2614(89)87234-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery J. (2004). Nickel-catalyzed reductive cyclizations and couplings. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 3890–3908. 10.1002/anie.200300634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E. F., Murugavel R., Roesky H. W. (1997). Organometallic Fluorides: compounds containing carbon-metal-fluorine fragments of d-block metals. Chem. Rev. 97, 3425–3468. 10.1021/cr960365v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negishi E. (1982). Palladium- or nickel-catalyzed cross coupling. A new selective method for carbon-carbon bond formation. Acc. Chem. Res. 15, 340–348. 10.1021/ar00083a001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi M., Kambara T., Hatanaka T., Saijo H., Doi R., Ogoshi S. (2011). Palladium-catalyzed coupling reactions of tetrafluoroethylene with arylzinc compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 3256–3259. 10.1021/ja109911p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakoda K., Mihara J., Ichikawa J. (2005). Heck-type 5-endo-trig cyclization promoted by vinylic fluorines: synthesis of 5-fluoro-3H-pyrroles. Chem. Commun. 37, 4684–4686. 10.1039/b510039a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens P. J., Devlin F. J., Chaobalowski C. F., Frisch M. J. (1994). Ab Initio calculation of vibrational absorption and circular dichroism spectra using density functional force fields. J. Phys. Chem. 98, 11623–11627. 10.1021/j100096a001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tamao K., Kodama S., Nakajima I., Kumada M., Minato A., Suzuki K. (1982). Nickel-phosphine complex-catalyzed Grignard coupling. II. Grignard coupling of heterocyclic compounds. Tetrahedron 38, 3347–3354. 10.1016/0040-4020(82)80117-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Truhlar D. G. (2008). Molecular modeling of complex chemical systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 16824–16827. 10.1021/ja808927h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadt W. R., Hay P. J. (1985). Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for main group elements Na to Bi. J. Chem. Phys. 82, 284–298. 10.1063/1.448800 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Liu Y., Chen G., Pei G., Bi S. (2017). Theoretical insight into C(sp3)-F bond activations and origins of chemo- and regioselectivities of “Tunable” nickel-mediated /-catalyzed couplings of 2 trifluoromethyl-1-alkenes with alkynes. Organometallics 36, 3739–3749. 10.1021/acs.organomet.7b00514 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Zhou Q., Yu W., Li T., Wu G., Zhang Y., et al. (2015). Cu(I)-catalyzed cross-coupling of terminal alkynes with trifluoromethyl ketone N-tosylhydrazones: access to 1,1-difluoro-1,3-enynes. Org. Lett. 17, 2474–2477. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Truhlar D. G. (2008a). Density functionals with broad applicability in chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 41, 157–167. 10.1021/ar700111a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Truhlar D. G. (2008b). The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 120, 215–241. 10.1007/s00214-007-0310-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Truhlar D. G. (2009). Benchmark energetic data in a model system for Grubbs II metathesis catalysis and their use for the development, assessment, and validation of electronic structure methods. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 5, 324–333. 10.1021/ct800386d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.