Abstract

Collecting useful data on a sufficiently large cohort of pregnancies in women with rheumatic disease is a challenge. The original manuscripts that demonstrated the dangers of pregnancy in women with lupus were relatively small case series. As larger prospective cohorts were collected by university-based experts, however, greater safety was demonstrated and the current norms of treatment were determined. In recent years, larger administrative databases have been tapped to study pregnancies not managed within university clinics and to study the long-term impact of maternal rheumatic disease on the offspring. Each of these methods of study has both strengths and weaknesses, adding a unique piece of data to our overall knowledge. We will discuss a range of approaches to the study of rheumatic disease in pregnancy, covering the potential benefits that each brings as well as the biases that can impact study results. When the results of studies are viewed through these lenses, each can contribute to our larger understanding of the rheumatic diseases in pregnancy.

Keywords: systematic lupus erythematosus and autoimmunity, rheumatoid arthritis, pregnancy and rheumatic disease, study design, autoinflammatory conditions

Rheumatology key messages

The infrequency of pregnancies in rheumatic diseases creates challenges in collecting sufficient reliable data.

Data sources in rheumatic disease pregnancies include single-clinic data, registries and administrative databases.

Data sources present methodological considerations that must be carefully addressed when assessing reproductive outcomes in rheumatic diseases.

Introduction

Because of the relative infrequency of pregnancy in women with rheumatic diseases, collecting datasets of sufficient size with reliable data can be challenging. Managing pregnancy to optimize the outcome, meaning limiting the risks of pregnancy loss, birth defect and preterm birth while preventing long-term damage to the mother, requires balancing disease activity and medication. Ideally, we want to identify data sources that can provide the granular data required to understand the nuances of treatment effects but that also provide sufficient numbers of pregnancies with appropriate control groups. Data options range from the lone investigator collecting data from clinic, to electronic medical record (EMR)-based registries, to administrative claims data, to nationwide registries. The advantages and drawbacks that these options bring will be discussed to spark debate and consideration for how best to move our knowledge of managing rheumatic diseases in pregnancy forward.

Administrative databases

Administrative databases are defined as large datasets collected as part of clinical care that are primarily for administrative or billing purposes, but can be used to study health care delivery and outcomes [1]. The increased availability of administrative data for research purposes has allowed for more rapid collection of data on subjects with rare diseases and the large sample size has many advantages. Because most administrative data are based on electronic health records or claims data, included subjects generally represent a population-based cohort, rather than subjects who may voluntarily participate in a registry, or subject who are seen exclusively at tertiary care medical centres. Similarly, large numbers of control subjects can be easily identified within the dataset who may represent non-diseased individuals as comparators, whose data are collected in the same fashion as cases of interest. Additionally, as the data are generated at the time of the encounter, it is by nature prospective and systematic, without the inherent biases of recall of past exposures, or self-selection by volunteer status.

There are many different types of administrative datasets worldwide, and it is important to understand the type of data present and unavailable in each dataset, validity and potential misclassification of data, as well as the ability to link maternal data with infant data.

As the USA does not have a nationwide health system or systematic capture of medical data, the ability to collect comprehensive medical data on a truly population-based cohort is necessarily limited. However, several datasets are available that may be relevant to research into pregnancy outcomes in rheumatic disease populations. Perhaps the most commonly used are administrative data based on medical claims, either by publicly funded insurers (Medicaid) or private insurers. These data are quite valuable in that they contain inpatient and outpatient diagnoses and procedures as well as prescription medication data linked to individuals. Unfortunately, because of the fragmentation of health care in the USA, individuals may not retain extended enrolment with any specific insurer, making long-term evaluation across multiple pregnancies more difficult. Numerous algorithms are currently utilized to maximize sensitivity and specificity of diagnoses made on claims data [2, 3]. Additionally, important variables may not be captured in claims data including lifestyle variables (smoking, alcohol, exercise), prior reproductive history, results of laboratory studies and variables on disease activity or severity.

More granularity of data in the USA may be obtained by using EMR data that often include laboratory and imaging data in addition to variables available in administrative datasets. The government-sponsored Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute has funded multiple large collaborative projects working to synchronize EMR data from a range of health systems, which may provide access to useful data in the future. These collaboratives work from a Common Data Model, which is a limited dataset including billing, prescribing and laboratory data. Additionally, data fields and key word searches may include information regarding vital signs, BMI, lifestyle variables, reproductive history and even data regarding gestational age and other antepartum pregnancy variables. In general, patient reported outcomes and standardized assessments of disease activity and severity remain unavailable as they are specific composite measures of disease that are not routinely captured for administrative or billing purposes. Using such datasets is extremely complex and requires sophisticated analyses, thus increasing the cost, time and required expertise of performing such studies.

Population-based surveillance registers

Population-based surveillance registers offer a systematic data collection on specific outcomes, usually based on mandatory reporting within a country or region. They usually contain data on all outpatient visits, hospitalizations and drug prescriptions filled for a given population over a prolonged period of time. Some registers will also collect self-reported information, particularly on certain exposures of interest.

One example of population-based surveillance registers is the Nordic Birth Registers, which cover Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden, encompassing ∼25 million subjects [4, 5]. Each of the Nordic countries has kept medical birth registers for decades, all with compulsory notification. Linkage to other registers and national healthcare databases is possible, such as outpatient, hospitalization and prescription databases. They capture exposure and outcome data from a representative sample of births. All registers contain basic information on the mother, neonate and father. In some of these registers, data on lifestyle factors such as alcohol, smoking and BMI are available; a drawback is that they do not include information about first trimester pregnancy losses.

The Canadian administrative healthcare databases are also considered a type of population-based surveillance register. Each Canadian province has its own province-based surveillance register. As an example, Quebec’s administrative databases cover all residents in the province (>8 million people) and collect information on all hospitalizations, physician visits and procedures. In addition, they include data on drug prescriptions filled for residents on the public drug plan, which covers recipients of social assistance and workers and their family without access to a private drug plan, representing about a third of the population.

Furthermore, Quebec’s Institute of Statistics monitors important vital statistics, including live birth and stillbirth rates, with a mandatory reporting of gestational age at birth (based on date of last menstrual period) as well as cause of stillbirth. All these databases can be linked to provide a rich source of information to assemble a population-based cohort of pregnancies and/or deliveries, with available mother and child linkage, creating a cohort of offspring with antenatal exposure of interest. One such cohort, the Offspring of SLE mother Registry (OSLER), has been assembled to assess the risk of long-term health outcomes and stillbirths in children born to women with SLE (see Table 1) [6, 7].

Table 1.

Data in the OSLER cohort of offspring of women with SLE, extracted from the administrative databases

| Category | Available variables in OSLER |

|---|---|

| Outcomes and maternal comorbidities | Diagnostic codes from hospitalizations and/or physician visits |

| Procedure codes | |

| Maternal SES covariates | Marital status |

| Education | |

| Race | |

| Birthplace and language | |

| Region of residence | Postal code |

| Obstetrical variables | Gestational age |

| Birth weight | |

| Vital status at birth | |

| Birth order | |

| Multiple birth | |

| Medication (subsample) | Any drug dispensed (outside the hospital) |

| Drug identification number |

OSLER: Offspring of SLE mother Registry; SES: socio-economic status.

OSLER includes 719 children born to mothers with SLE and 8493 matched unexposed children. To create this large cohort, the investigators identified all women with SLE who had at least one hospitalization for a delivery (including both stillbirths and live births) between January 1989 and December 2009, using data from the Quebec hospitalization and physician billing databases.

Women were identified as SLE cases (based on a previously validated definition [8], using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) code 710.0 or ICD-10 code M32) if they had any of the following: (i) at least one hospitalization with a diagnosis of SLE (either primary or non-primary) prior to the delivery; (ii) a diagnosis of SLE (either primary or non-primary) recorded at the time of their hospitalization for delivery; or (iii) at least two physician visits with a diagnosis of SLE, occurring 2 months to 2 years apart, prior to the delivery. From these databases, a general population control group was composed of women matched at least 4:1 for age and year of delivery, who did not have a diagnosis of SLE prior to or at the time of delivery.

Mother–child linkage was done using the encrypted mother’s number, which is present in every child’s file in the physician billing and hospitalization databases, and where it remains through childhood, leading to very few linkage failures (<2%). Those children born live or stillborn formed the basis of the OSLER cohort for outcome ascertainment, the exposed group consisting of children born to women with SLE, and the unexposed group consisting of children born to women without SLE.

The cohort of children described above was linked to the hospitalization and physician billing databases to determine hospitalizations and all diagnoses occurring throughout the study interval of these offspring. This study interval spanned from birth to the first of the following: end of eligibility for provincial healthcare coverage (i.e. migration from Quebec), event of interest (e.g. congenital heart defect, autism spectrum disorders), a pre-defined age (12 months for congenital heart defect and 18 years for autism spectrum disorders), death or end of study (i.e. 31 December 2009) [6, 7].

Advantages of administrative databases for reproductive studies

Administrative databases offer several advantages for the study of reproductive issues in women with rheumatic diseases. Large sample size makes it possible to study outcomes associated with rare exposures, such as SLE, which only affects 0.1% of females of childbearing age. Alternatively, it provides sufficient power to assess rare outcomes (such as neurodevelopmental disorders), which is not feasible in clinic-based prospective cohort studies. In addition, administrative databases allow access to data that have already been collected in a systematic manner, facilitating the conducting of observational studies, which can be undertaken rapidly and at relatively low cost. Furthermore, several databases provide population-based data that cover the entire population of a geographic region, which makes it more likely that the study sample will be representative of the target population. As informed consent is generally not required for selection of a subject in the study, study designs using this data source are less prone to selection bias from non-response. Moreover, the use of administrative databases also eases the selection of a control group from the same source population.

Challenging issues specific to pregnancy in administrative databases

Timing of pregnancy

Understanding the timing of pregnancy using administrative data presents its own set of challenges, particularly as they relate to the time of conception and exposures related to specific gestational ages. This can be extremely important when considering issues of potential teratogenicity, where there is often a specific window of days to weeks during organogenesis where embryos are most vulnerable in early pregnancy. Given that maternal rheumatic diseases often rely on chronic use of medications to manage symptoms, the timing of pregnancy onset with the discontinuation of chronic medications can be critical. Additionally, short term exposures to medications during early pregnancy (steroid bursts, infusion therapeutics, antibiotics and vaccines) may potentially affect pregnancy outcomes and need to be captured accurately.

Parity

Because pregnancy outcomes, and even the decision to proceed with additional pregnancies, depend heavily upon the outcome of previous pregnancies, classifying pregnancies into first birth vs subsequent births is of the utmost importance [9, 10]. It is not as critical to determine the order of pregnancies after the first birth. Pregnancy outcome studies will have dramatically different results when only first births are included in the analysis compared with subsequent births, even in cases where only one birth per woman is included. Further complications in analysis and interpretation arise when multiple births per woman are included in the dataset as each birth is not independent of the others. The generalized estimating equation can be used to account for this lack of independence, as long as the pregnancies can be appropriately clustered according to mother [11]. In the USA, outside of electronic medical records, most administrative datasets do not include variables about parity, and it cannot be assumed that the first pregnancy during the period of data capture in a dataset is necessarily the first pregnancy for that woman as enrolment periods in health insurance do not cover the entire reproductive history. Datasets from countries with more complete birth data capture are less likely to misclassify first versus subsequent birth.

Congenital malformations

With increasing use of polypharmacy (inadvertently prior to pregnancy discovery or intentionally to treat maternal illness) during the peri-conceptional period and into pregnancy comes increasing concerns for identifying any associations with congenital malformations and medication exposure. The large numbers of subjects available through administrative datasets can be ideal for studying rare outcomes of uncommon antenatal exposures. However, several issues regarding the use of administrative datasets for teratogenicity studies must be addressed. The first issue is the ability to link mothers’ records to those of their infants. In the USA, state birth certificate data are often the only infant data available to determine infant outcomes, and the ability and ease of linking these data to maternal data depend on the specific datasets and user access to such data [12]. Neonatal outcomes are limited to that which could be diagnosed at birth. In other cases, infant medical records can be linked to maternal records. Comprehensive medical records for infants will contain more detailed data on neonatal outcomes and complications identified beyond the delivery period than will data obtained solely from birth certificates. As described above, there are inherent difficulties in accurately determining the onset of pregnancy to a precision of days to weeks for early antenatal exposure to medications.

Once maternal medical records are linked to infant data, the diagnostic accuracy and completeness of ascertainment of congenital anomalies from these records becomes critical. A major concern of using administrative databases is related to the validity of the diagnostic information, because diseases are primarily coded for billing and not for research purposes. One can try to use previously validated case definitions. However, they are not always available and when available, none are 100% sensitive and specific. One recent study comparing birth certificate data to administrative health plan data found a high positive predictive value (PPV) for demographic and some pregnancy outcome data on birth certificates, including gestational age, birth weight, race/ethnicity and prior maternal obstetric history [13]. Unfortunately, PPVs for selected congenital anomalies were much lower for both birth certificate data and administrative claims data. For example, using medical record review as the gold standard, the PPV for cardiac defects in the Tennessee Medicaid population was only 35.7% for birth certificate data, rising to 74.5% for claims data [14]. Arguably, this is unacceptably low to make meaningful interpretations regarding teratogenicity.

The last, and perhaps most challenging, aspect to studying teratogenicity is the issue of the appropriate sample size to determine associations with reasonable power. Power calculations are influenced both by the prevalence of the specific congenital anomaly (estimates of the overall birth defect rate in the general population are 3–5% of pregnancies) and the magnitude of the effect, or the increased risk of the anomaly in the exposed compared with the unexposed group that is considered clinically significant. Given the very low prevalence of specific congenital anomalies in the general obstetric population, tens to hundreds of thousands of pregnancies must be analysed to detect even a large increase in risk [15]. And this is before adjusting for relevant covariates, confounders and multiple comparisons. To address the issue of imperfect case ascertainment, one can use Bayesian latent class models, which uses various case definitions with each contributing some information about the latent case status of each individual instead of trying to identify a ‘disease case’ (or outcome) with certainty [16]. Subjects are thus assigned a probability of being a disease case. This method can be used to correct for all sources of uncertainty related to case ascertainment.

The need for such large sample sizes to do this type of research is among the greatest strengths of administrative data. However, the tremendous increase in sample size often comes with a loss of granularity regarding the reliability and precision of data capture in settings where large scale validation and potential for more careful data scrutiny are largely unavailable.

Because the ramifications of publishing associations between specific manifestations and congenital anomalies can be profound and affect the management of serious maternal conditions prior to and during conception, researchers must be very careful to address all of the relevant issues regarding exposure and outcome data. These include accurate timing of antenatal exposure, the potential for concomitant medication exposures and other potential causes of congenital malformations, rigorous definitions and accurate ascertainment of congenital anomalies, and adequate sample sizes of both exposed and unexposed pregnancies.

As an example, if we wanted to study the effect of maternal SLE on the risk of birth defect in the offspring, maternal alcohol intake could be an important unmeasured confounder in some administrative databases. Using previously described formulas, one can determine how large the maternal SLE–alcohol association in the cohort would have to be so that adjusting for the presence of the maternal confounder (i.e. alcohol intake) during pregnancy would remove an apparent maternal SLE–birth defect association.

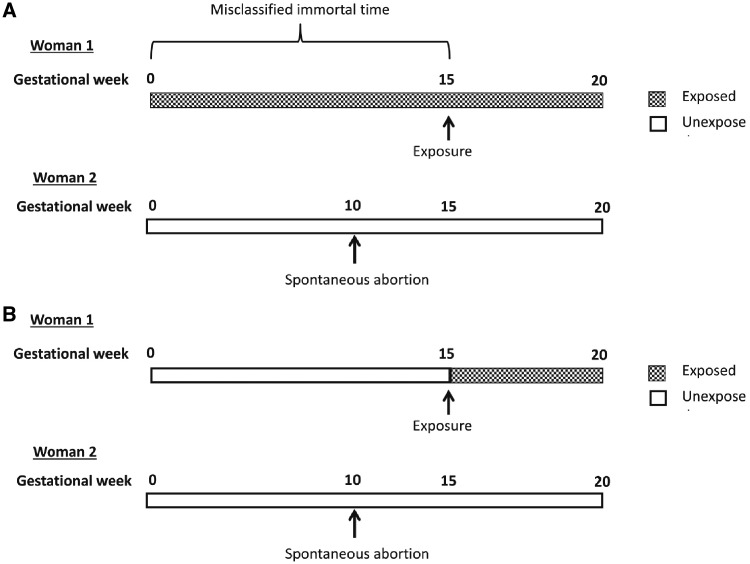

Observational studies using administrative databases might also be plagued by immortal time bias. Immortal time refers to a time period over cohort follow-up during which, by design, subjects could not have died (or have the outcome/event) [17]. As an example, Daniel et al. [18] described the potential for immortal bias in assessing the effect of maternal NSAID exposure in pregnancy on fetal death before 20 weeks of gestation (see Fig. 1). If NSAID exposure is based on at least one prescription filled before 20 weeks of gestation, exposed fetuses are necessarily immortal during the time span between conception and exposure. By contrast, fetuses in the unexposed group have no such advantage because they could have had the outcome of fetal death at any time during follow-up. To avoid introducing immortal time into our analysis, the solution is simply to categorize follow-up time for each subject according to exposure category.

Fig. 1.

Example of immortal-time bias in study of association of NSAIDs with fetal loss

Reprinted from American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 212/3, Daniel S et al. Immortal time bias in drug safety cohort studies: spontaneous abortion following nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug exposure, pp. 307.e1–6, Copyright (2015), with permission from Elsevier.

In summary, administrative databases are a very useful and powerful data source for the conduct of rheumatic disease research, such as investigating reproductive issues. However, we must take great caution in dealing with potential limitations, and use different strategies to address these.

Prospective, clinic-based pregnancy registries

Prospective pregnancy registries, carefully collected in specialty clinics, can provide a wealth of information beyond what can be collected from administrative databases. Single-site lupus registries, such as the Hopkins Lupus Cohort and the Toronto Lupus Cohort, were the first sources for the data that suggested women with lupus could have safe pregnancies, changing the lives of many women with lupus. In 1980, The Toronto Lupus Cohort published data from 24 pregnancies in women with lupus, reporting that lupus is inactive in pregnancy if inactive at conception, despite a history of severe disease [19]. On the other hand, in 1991, the first 40 pregnancies in the Hopkins Lupus Cohort were published, showing an increased rate of flare in pregnancy [20]. Single-site registries are limited by the rate of enrolment, preventing them from answering the more nuanced questions that now confront us. In addition, they often lack a healthy control comparison group, as non-diseased patients are not typically seen by the research team. The Duke Autoimmunity in Pregnancy Registry, for example, has enrolled over 400 pregnancies in 8 years, with complete data on 122 pregnancies in women with lupus, 56 pregnancies in women with RA and 19 pregnancies in women with PsA. Over the protracted time that it takes to collect sufficient pregnancies, the obstetric and rheumatic practices may have changed, challenging our ability to ascribe cause and effect. Additionally, these cohorts are limited to the subset of patients who have access to specialty clinics and may not be generalizable to the general rheumatic disease population.

Multi-site registries may be able to overcome some of these drawbacks. By having pregnancies collected at a number of sites, the accrual would be expected to be faster and the patients may be somewhat more generalizable, though they will still be managed, most likely, by specialists in the field. The Predictors of Pregnancy Outcome: Biomarkers in Antiphospholipid Antibody Syndrome and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus study had the basic format of a multi-site registry with pregnancies enrolled from nine sites [21]. Accrual remained slow, however, taking a decade to accrue almost 350 pregnancies, and was perhaps hampered by the specific entry criteria that limited enrolment to the first trimester and a protocol that required frequent office visits and blood samples. The trade-off, however, is very rich data from a specific and relatively uniform patient population, as well as an extensive repository to fuel translational work.

Another model for data collection is the Pregnancy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Neonatal Outcomes (PIANO) Registry, which prospectively enrols pregnant women with IBD from 30 IBD centres around the USA. This registry has enrolled 1564 pregnancies over the past 10 years. Patients may either be enrolled from the Crohn’s Colitis Foundation Clinical Alliance site, or may be enrolled directly by the lead site after referral from their local gastroenterologist. The registry is funded by the Crohn’s Colitis Foundation, with no pharmaceutical funding. Philanthropic funds are used to supplement the foundation budget. The PIANO Registry has provided important contributions to the management of IBD in pregnancy. The safety of monoclonal antibody medications in pregnancy, including the effect on congenital malformations, IBD flare and infant infection risk, has been studied. Placental and breast milk transfer of mAb studies has been demonstrated and developmental milestones up to 4 years of age in exposed infants have been described.

We suggest that rheumatologists interested in furthering our understanding of how best to manage rheumatic pregnancies collaborate to collect prospective data in multi-site registries. There are several feasible options for accomplishing this aim. One is to create a stand-alone registry, similar to the PIANO registry, into which collaborating rheumatologists enter patient data. In this format, rheumatologists with a focus on pregnancy could enrol pregnant women with a range of rheumatic diseases into a central database. The local data could be held at the investigator’s institution and contributed periodically, or could be entered directly into an internet-based central registry. Another model to pull data from pregnancies out of multiple locally held disease-specific registries. For example, rheumatologists with an ongoing prospective lupus registry could agree to collect similar pregnancy parameters and outcomes, then periodically pull the data out of their lupus registry and add it to a central dataset of pregnancies in women with lupus. These registries frequently collect extensive data at each visit, creating a rich database, but they may not be able to combine easily.

Data collection

All studies struggle to balance collecting all the data one could ever possibly want and the feasibility of collecting data in a busy clinic. Striking the proper balance is essential to establishing a successful registry. It is important that it contain sufficient data to allow a wide range of questions, both anticipated and unanticipated at the start of the registry. However, burdening busy clinicians and under-funded coordinators with long and complicated forms that request data not easily obtained in clinic will increase the likelihood that incorrect or incomplete data will be recorded.

One reasonable option to assist in data collection is for the patients to directly enter some of the required data into a computer-based survey. Patients can enter basic demographics, the basics of prior pregnancy outcomes and basic information about their disease history. Details on past pregnancy outcomes and disease history may require validation from medical record review as they are subject to recall bias. They can also complete validated surveys about their physical functioning and visual analogue scales for their pain and perceived level of disease activity. Some diseases, such as RA and AS, have patient-reported outcomes that correlate well with physician-reported disease activity measures, making these reliable and useful assessments of disease activity [22, 23]. Women with lupus or UCTD may not be able to provide as reliable assessments of inflammatory disease activity as many measures are laboratory based and not necessarily symptomatic [24].

We have compiled basic lists in Tables 2 and 3 of the essential and optimal pregnancy outcomes that can be collected in a registry. Certainly, more data can be collected to answer more specific questions, but we focused on the most important information needed to answer questions about disease activity, medication use and pregnancy outcome.

Table 2.

Essential and optimal information to collect for a pregnancy registry—disease history

| Maternal information | Rheumatic information | Changes in pregnancy |

|---|---|---|

| Essential Information | ||

|

|

|

| Optimal Information | ||

|

|

|

The minimal information is what is needed to complete basic analyses about pregnancy outcomes and predictors. The optimal information will allow expansion to a wider range of hypotheses and questions, but will increase the effort required for data collection.

Table 3.

Essential and optimal information to collect for a pregnancy registry—pregnancy history

| Pregnancy outcomes | Infant outcomes | Maternal outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Essential Information | ||

|

|

|

| Optimal Information | ||

|

|

|

The minimal information will allow the classification of each pregnancy for the mother and infant, but the optimal information will allow further understanding of the nuanced outcomes. While much of the minimal information can be collected from the patient, many of the optimal measures require access to the patient’s medical record.

Potential limitations

While multisite registries provide an excellent opportunity to obtain larger datasets, the data collected can be challenging to interpret. One important component of an effective registry is that the data be collected prospectively, so that physicians and patients record medication exposure and levels of disease activity before being biased by knowing the outcome of the pregnancy. Another challenge is documenting accurate medications and compliance. We know that an estimated 20% of lupus patients recorded as taking HCQ have undetectable blood levels in a university clinic [25]. Even in pregnancy, an estimated 30% of patients are non-compliant with HCQ at some point in pregnancy [26]. When compliance is not recorded, we may incorrectly attribute improvement or damage to a medication that a patient is not actually taking. A brief patient-reported medication list during or after pregnancy might overcome this challenge.

A final drawback to multisite registries is the wide range of treatment patterns used by rheumatologists. The Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance registry, a multisite paediatric rheumatology registry, has sought to overcome this obstacle by developing consensus treatment algorithms that the treating physician and patient can select between as they see fit [27]. This somewhat restricts variety in treatment plans and can facilitate comparative effectiveness studies of the treatment algorithms.

In conclusion, multiple data sources are available to study reproductive outcomes in women with rheumatic diseases. However, they all present some potential methodological considerations that need to be carefully addressed in order to obtain valid findings.

Supplement: This project was approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board.

Funding: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health [R13AR070007].

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Cadarette SM. An introduction to health care administrative data. Can J Hosp Pharm 2015;68:232–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moores KG, Sathe NA.. A systematic review of validated methods for identifying systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) using administrative claims data. Vaccine 2013;31 (Suppl 10):K62–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chung CP, Rohan P, Krishnaswami S, McPheeters ML.. A systematic review of validated methods for identifying patients with rheumatoid arthritis using administrative or claims data. Vaccine 2013;31 (Suppl 10):K41–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Langhoff-Roos J, Krebs L, Klungsøyr K. et al. The Nordic medical birth registers – a potential goldmine for clinical research. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2014;93:132–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Furu K, Wettermark B, Andersen M. et al. The Nordic countries as a cohort for pharmacoepidemiological research. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2010;106:86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vinet É, Pineau CA, Scott S. et al. Increased congenital heart defects in children born to women with systemic lupus erythematosus: results from the offspring of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Mothers Registry Study. Circulation 2015;131:149–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vinet É, Pineau CA, Clarke AE. et al. Increased risk of autism spectrum disorders in children born to women with systemic lupus erythematosus: results from a large population-based cohort. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:3201–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bernatsky S, Joseph L, Pineau CA. et al. A population-based assessment of systemic lupus erythematosus incidence and prevalence. Rheumatology 2007;46:1814–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wallenius M, Dalvesen KA, Daltveit AK, Skomsvoll JF.. Rheumatoid arthritis and outcome in first and subsequent births based on data from a national birth registry. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2014;93:302–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wallenius M, Salvesen KA, Daltveit AK, Skomsvoll JF.. Systemic lupus erythematosus and outcomes in first and subsequent births based on data from a national birth registry. Arthritis Care Res 2014;66:1718–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Islam MA, Chowdhury RI.. Generalized estimating equation In: Analysis of Repeated Measures Data. Singapore: Springer, 2017: Chapter 12, 161–68. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Johnson KE, Beaton SJ, Andrade SE. et al. Methods of linking mothers and infants using health plan data for studies of pregnancy outcomes. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2013;22:776–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Andrade SE, Scott PE, Davis RL. et al. Validity of health plan and birth certificate data for pregnancy research. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2013;22:7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cooper WO, Hernandez-Diaz S, Gideon P. et al. Positive predictive value of computerized records for major congenital malformations. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2008;17:455–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tinker SC, Gilboa S, Reefhuis J. et al. Challenges in studying modifiable risk factors for birth defects. Curr Epidemiol Rep 2015;2:23–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Joseph L, Gyorkos TW, Coupal L.. Bayesian estimation of disease prevalence and the parameters of diagnostic tests in the absence of a gold standard. Am J Epidemiol 1995;141:263–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Suissa S. Immortal time bias in pharmacoepidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167:492–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Daniel S, Koren G, Lunenfeld E, Levy A.. Immortal time bias in drug safety cohort studies: spontaneous abortion following nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug exposure. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212:307.e1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tozman EC, Urowitz MB, Gladman DD.. Systemic lupus erythematosus and pregnancy. J Rheumatol 1980;7:624–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Petri M, Howard D, Repke J.. Frequency of lupus flare in pregnancy. The Hopkins Lupus Pregnancy Center experience. Arthritis Rheum 1991;34:1538–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Buyon JP, Kim MY, Guerra MM. et al. Predictors of pregnancy outcome in a prospective, multiethnic cohort of lupus patients. Ann Int Med 2015;163:153–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bruce B, Fries JF.. The Stanford health assessment questionnaire: dimensions and practical applications. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003;1:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG. et al. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J Rheumatol 1994;21:2286–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Castrejón I, Tani C, Jolly M, Huang A, Mosca M.. Indices to assess patients with systemic lupus erythematosus in clinical trials, long-term observational studies, and clinical care. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2014;32 (5 Suppl 85):S-85–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Durcan L, Clarke WA, Magder LS, Petri M.. Hydroxychloroquine blood levels in systemic lupus erythematosus: clarifying dosing controversies and improving adherence. J Rheumatol 2015;42:2092–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Balevic S, Cohen-Wolkowiez M, Eudy AM, Schanberg LE, Clowse MEB.. Hydroxychloroquine level decreases throughout pregnancy: implications for maternal and neonatal outcomes [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69 (Suppl 10):Abstract 1296. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ringold S, Weiss PF, Colbert RA. et al. Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance consensus treatment plans for new-onset polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Research Committee of the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance. Arthritis Care Res 2014;66:1063–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]