Summary

T helper 17 (Th17) cells play critical roles in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. The lineage‐specific transcription factor ROR γt is the key regulator for Th17 cell fate commitment. A substantial number of studies have established the importance of transforming growth factor β (TGF‐β) ‐dependent pathways in inducing ROR γt expression and Th17 differentiation. TGF‐β superfamily members TGF‐β 1, TGF‐β 3 or activin A, in concert with interleukin‐6 or interleukin‐21, differentiate naive T cells into Th17 cells. Alternatively, Th17 differentiation can occur through TGF‐β‐independent pathways. However, the mechanism of how TGF‐β‐dependent and TGF‐β‐independent pathways control Th17 differentiation remains controversial. This review focuses on the perplexing role of TGF‐β in Th17 differentiation, depicts the requirement of TGF‐β for Th17 development, and underscores the multiple mechanisms underlying TGF‐β‐promoted Th17 generation, pathogenicity and plasticity. With new insights and comprehension from recent findings, this review specifically tackles the involvement of the canonical TGF‐β signalling components, SMAD2, SMAD3 and SMAD4, summarizes diverse SMAD‐independent mechanisms, and highlights the importance of TGF‐β signalling in balancing the reciprocal conversion of Th17 and regulatory T cells. Finally, this review includes discussions and perspectives and raises important mechanistic questions about the role of TGF‐β in Th17 generation and function.

Keywords: SMAD, T helper 17 differentiation, transforming growth factor β

Cytokine milieu for T helper 17 differentiation

T helper 17 (Th17) cells were identified in 2005 as a new subset of CD4+ T helper cells producing interleukin‐17 (IL‐17).1, 2 In response to environmental cues, naive T cells differentiate into Th17 effector cells (Fig. 1). The Th17 differentiation requires both inflammatory cytokine [e.g. IL‐6, or IL‐21] and transforming growth factor β (TGF‐β) to efficiently induce the lineage‐specific transcription factor retinoic‐acid‐receptor‐related orphan nuclear receptor γt (RORγt) as well as IL‐17 production.3 T helper 17 cells are critically involved in host defence, inflammation and autoimmunity.4 The Th17 responses contribute to the pathogenesis of diverse human diseases, including psoriasis, asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease and multiple sclerosis.5, 6 A better understanding of Th17 differentiation would therefore lay the basis for therapeutic interventions.7

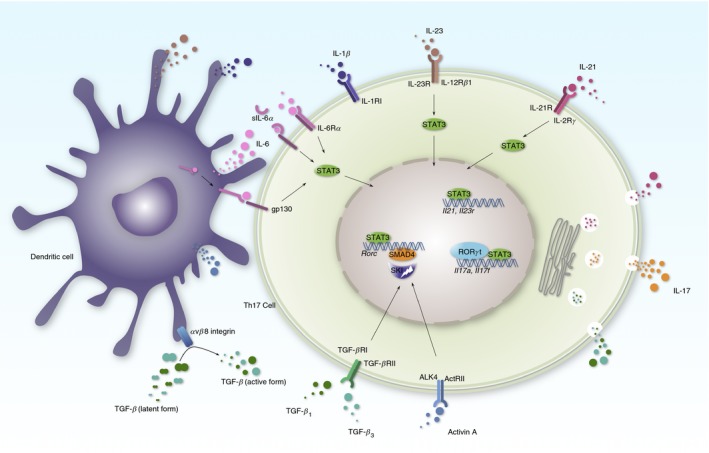

Figure 1.

T helper 17 (Th17) differentiation. Interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) or IL‐21 activates signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) to potentiate Rorc expression, which encodes the retinoic‐acid‐receptor‐related orphan nuclear receptor γt (ROR γt) transcription factor. IL‐6 activates STAT3 through classic, trans or cluster signalling pathways. Additional transforming growth factor‐β (TGF‐β) or activin A degrades SKI to reverse the SKI/SMAD4 complex imposed repression on Rorc transcription. Unleashed ROR γt binds to the Il17a, Il17f loci and drives T cells to produces Th17 cytokines, e.g. IL‐17A, IL‐17F, IL‐21 and TGF‐β. Dendritic cells produce multiple cytokines to promote Th17 differentiation, such as IL‐6, IL1‐β, IL‐23 and activin A. Dendritic cells also express integrin α v/β 8 to process the latent form of TGF‐β to the active form.

Inflammatory cytokines

Interleukin‐6 is characterized as an inflammatory cytokine, together with TGF‐β featuring Th17 induction activity.8, 9 Engagement of IL‐6 with its receptor leads to activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), which further potentiates RORγt transcription.4 Although various haematopoietic and non‐haematopoietic cells can produce IL‐6, a recent study showed that Sirpα + dendritic cells are essential for pathogenic Th17 cells by trans‐presenting IL‐6 to T cells during the process of cognate interaction.10

As an alternative cytokine, IL‐21 also can stimulate STAT3 activation. Interleukin‐21 in combination with TGF‐β leads to RORγt expression and Th17 differentiation independent of IL‐6.11, 12, 13, 14 In addition, IL‐6 induces IL‐21 during Th17 differentiation to further enhance the Th17 programme.

Other cytokines also play important roles in the development of Th17 cells. Interleukin‐1 signalling is indispensable for Th17‐mediated autoimmunity in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE),15 and is necessary for early Th17 differentiation in vivo.16 It is also critical for the expansion, but not the generation, of autoreactive granulocyte–macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (GM‐CSF) ‐positive Th17 cells.17 Additionally, IL‐1 enhances Th17 differentiation by inhibiting TGF‐β‐induced Foxp3 expression.18

Interleukin‐23 is capable of activating the STAT3 pathway and promoting Th17 lineage maintenance but not commitment.19 Importantly, T cells exposed to IL‐23 have promoted expression of GM‐CSF and IL‐23 receptor (IL‐23R) to become more pathogenic.20, 21

It is still unclear if there are other unrecognized cytokines that can act functionally like IL‐6 or IL‐21 to initiate Th17 differentiation with TGF‐β. It has also been elusive whether STAT3 activation is the only major function for IL‐6 and IL‐21 to induce Th17, or whether these cytokines have other important targets to synergize with TGF‐β signalling and induce Th17 differentiation.

Requirement of TGF‐β for Th17 differentiation

Transforming growth factor‐β is a regulatory cytokine, exerting pleiotropic functions in T‐cell development, homeostasis, tolerance and differentiation.22, 23 The TGF‐β is produced as an inactive form in complex with latency‐associated peptide and latent TGF‐β‐binding protein, and is further activated by disengaging from this large latent complex. Multiple mechanisms are involved during this process, including plasmin, matrix metalloproteases, thrombospondin‐1 and integrins.22, 24, 25 Integrin binds to latency‐associated peptide and induces the release of mature TGF‐β, which provides an additional layer of mechanistic regulation. For example, although dendritic cells do not produce TGF‐β, these cells are important for α v/β 8 integrin‐mediated TGF‐β activation to exert biological functions such as inducing Th17 differentiation.26 The α v/β 8 integrin transcription in antigen‐presenting cells depends on interferon regulatory factor 8 (IRF8). Mice with IRF8 deficiency in antigen‐presenting cells, but not T cells, fail to generate Th17 cells and were resistant to EAE.27

Transforming growth factor‐β established its requirement in murine models shortly after Th17 cells were identified.8, 9, 28 Mice that were TGF‐β 1 deficient exhibited profoundly diminished Th17 cells in all tissue sites.27 Mice with TGF‐β 1 deficiency in T cells were also defective in Th17 differentiation as well as the onset of EAE.29 Mice with TGF‐β signalling blockade by a dominant negative form of TGF‐β receptor II (CD4dnTGFβRII) or by a TGF‐β‐specific antibody failed to differentiate naive T cells to Th17 cells and were protected from EAE,30 whereas TGF‐β transgenic mice resulted in enhanced Th17 differentiation and more severe EAE.8 These data strongly suggest that TGF‐β is indispensable for Th17 differentiation.

Initially, human cells were considered not to require TGF‐β but only IL‐6 and IL‐1β, or IL‐1β and IL‐23 for Th17 differentiation.31, 32 Naive CD4+ T cells (defined by CD4+ CD45RA+ CD45RO− 32 or CD4+ CD45RA+ CCR7+ CD25− 31) used in these studies were sorted from peripheral blood, and so raised the concern of naiveté.33 In addition, there was possible TGF‐β contamination from the serum of culture medium. Therefore in later studies, naive cord blood CD4+ T cells (defined by CD3+ CD4+ CD25− HLA‐DR− CD45RA+,34 CD3+ CD4+ CD45RA+ CD45RO−,35 or CD4+ CD25− CD62L+ CD45RAhi 36) and serum‐free medium were used. With minimized TGF‐β source contamination from serum or platelets, and cord‐blood‐originated naive CD4+ T cells, these studies clarified that TGF‐β is indeed required for human cell Th17 differentiation.34, 35, 36 CD161+ CD4+ T‐cell precursors in umbilical cord blood and thymus were reported to constitutively express RORγt, IL‐23R and CCR6.37, 38 These cells produced IL‐17 in response to IL‐1β and IL‐23 without the need for TGF‐β.37, 39 Because most of the CD161+ cells express CD45RO,37, 40 these precursor cells might have a memory T‐cell phenotype. Both IL‐1β and IL‐23 could contribute to cell activation or expansion rather than to de novo Th17 differentiation. Moreover, TGF‐β is potent for skewing these CD161+ cells from Th1 towards Th17 after IL‐1β and IL‐23 stimulation.39 Collectively, these data suggest that TGF‐β plays an essential role in human Th17 differentiation.

TGF‐β source, TGF‐β superfamily and Th17 cell pathogenicity

There are three isoforms of TGF‐β: TGF‐β 1, TGF‐β 2 and TGF‐β 3.41 Many types of cell produce TGF‐β 1, and T cells are the important source of TGF‐β 1 to promote Th17 differentiation and to develop EAE,29 although the role of TGF‐β 1 in EAE induction is controversial.42, 43, 44 Despite the fact that Th1, Th2 and Th17 cells can express TGF‐β 1 after polarization, Th17 effector cells have the most increased production of TGF‐β 1. In vivo Th17 differentiation requires the autocrine TGF‐β 1.45 However, this finding is not consistent with the observation that autocrine TGF‐β produced by in vitro differentiated Th17 cells under IL‐6 + IL‐1β + IL‐23 conditions is not essential, as TGF‐β antibody blockade does not significantly reduce Th17 differentiation.46 Therefore, further debate on the role of autocrine TGF‐β produced by Th17 cells continues.

Foxp3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells could serve as another source of TGF‐β 1 production, which may induce naive T cells to differentiate into Th17 cells under in vitro co‐culture conditions.9 However, mice with TGF‐β 1 deletion specifically in Foxp3+ Treg cells show in a similar level of Th17 differentiation in an in vivo model of EAE, arguing that Foxp3+ Treg‐cell‐derived TGF‐β 1 is not essential for Th17 differentiation.45

The TGF‐β 1 produced by Treg cells or activated CD4+ T cells does not substantially affect the T‐cell activation in spleen and lymph nodes, but it is required for inhibiting Th1 differentiation in the gut.45 A subset of Treg cells, CD103+ Treg cells, possess very high suppressive activity and exist at sites of inflammation and mucosal tissues including gut,47, 48, 49 suggesting that the different microenvironment and local cytokine milieu may determine how TGF‐β influences Th17 differentiation and propagates disease progression.50

The sources of TGF‐β include stromal cells, immune cells and cancer cells, which provide a basis for versatile regulation in local immune responses.23 For example, gliadin‐specific Th17 cells from individuals with coeliac disease simultaneously express TGF‐β. This autocrine TGF‐β plays a positive regulatory role in IL‐17 production in intestinal mucosa.51 TGF‐β prevails in the intestine, and intestinal epithelial cells and dendritic cells are important sources of bioactive TGF‐β. In addition, CD103+ dendritic cells express a high level of integrin α v/β 8, and are specialized to activate latent TGF‐β.52, 53, 54 In healthy humans, about 4 ng/ml TGF‐β 1 circulates in plasma, therefore it may act in the manner of long‐range endocrine interactions between distant tissues. However, TGF‐β 2 and TGF‐β 3 are probably derived from local synthesis, as they are generally undetectable in plasma, and appear to act as local autocrine or paracrine regulators.55

Transforming growth factor‐β not only promotes Th17 differentiation but also determines the pathogenicity of Th17 cells. Researchers observed that TGF‐β 1‐induced Th17 cells are less pathogenic in EAE,20 whereas TGF‐β 3 leads to Th17 cells that are more pathogenic.21 TRIM28‐deficient T cells cause aberrant overexpression of TGF‐β 3 and contribute to the development and accumulation of pathogenic Th17 cells.56

Other than TGF‐β family cytokines, a TGF‐β superfamily member, activin A, was also reported to be capable of inducing Th17 differentiation in combination with IL‐6.57, 58

Because there are more than 33 human TGF‐β superfamily members, including TGF‐β, bone morphogenetic proteins and activins, and they share similar structures,23 it would be important to identify if there are more cytokines that could be functionally similar to TGF‐β 1, TGF‐β 3 and activin A during Th17 differentiation.

The diverse functions of the TGF‐β superfamily rely on their specific receptor signalling, which goes through different heteromeric type I and type II receptor complexes. Receptors TGFβRI (ALK5) and TGFβRII are mostly designated to TGF‐β, whereas receptors ACTRIB (ALK4) and ACTRIIs receive signalling from activins.23, 59 The differences in receptors could explain why activin A alone fails to induce Foxp3 whereas TGF‐β can induce Foxp3.60 However, TGF‐β 1 and TGF‐β 3 share identical receptors, but lead to distinct pathogenic profiles in Th17 cells.21 This suggests that there might be other undefined receptors or mechanisms in existence that require further investigation.

T helper 17 cells are recognized as important pathogenic effector cells in most EAE models.61 EAE is attenuated when mice are injected with anti‐IL‐17A antibody2, 62, 63 and IL‐17RA‐deficient mice are resistant to EAE.64 Interleukin‐17A deficiency results in reduced clinical EAE, although it does not fundamentally impede the incidence of disease induction.65, 66 Cytokines critical for Th17 differentiation, such as IL‐6,67, 68 IL‐21,11, 12 IL‐115 and IL‐23,69 are also required for EAE. Increasing evidence shows that several Th17‐expressed genes are especially vital for the pathogenicity of Th17 cells. For example, IL‐23R expression is shown to be critical for the generation of encephalitogenic Th17 cells,70, 71 and GM‐CSF‐deficient mice are resistant to EAE.72, 73, 74, 75 It appears that there are certain molecular networks associated with the pathogenicity of Th17 cells. Different TGF‐β signalling pathways produce different pathogenic programmes.21, 46, 76 As the Th17 cells are highly heterogeneous, the diversity of TGF‐β superfamily ligands and receptors provides a tool for investigating the essential mechanisms of Th17 pathogenicity.

TGF‐β‐independent Th17 cell differentiation

There are also studies showing that TGF‐β is dispensable for murine Th17 differentiation. In the presence of anti‐TGF‐β antibodies, STAT6 and T‐bet double‐deficient T cells can still differentiate into Th17 cells with IL‐6 alone.77, 78 These observations raise the debate on the requirement of TGF‐β in Th17 differentiation. However, TGF‐β antibody blockade, but not TGF‐β receptor signalling deficiency, could not rule out the possibility that there is still TGF‐β or that TGF‐β superfamily receptor signalling exists in these settings. Later, Ghoreschi et al.46 reported that although TGF‐βRI‐deficient mice or CD4dnTGFβRII mice were not able to induce EAE, there were similar amounts of Th17 cells in intestinal lamina propria compared with wild‐type mice. They also found that Th17 cells could be generated in vitro without TGF‐β using a combination of cytokines (IL‐6, IL‐1β and IL‐23) and that these Th17 cells were more pathogenic. These data suggest an alternative TGF‐β‐independent Th17 differentiation pattern. It also provides insight and opportunity to investigate the mechanism of TGF‐β‐dependent and TGF‐β‐independent Th17 differentiation and Th17 cell pathogenicity. Compared with TGF‐β, this cytokine combination had a relatively low ability to induce in vitro Th17 differentiation,16, 46 but enough to raise the argument that TGF‐β may not be necessary under certain environmental contexts.

To date, the mechanisms of how these Th17 cells are induced by cytokine combinations without requiring TGF‐β signalling, and how the downstream receptor signalling of IL‐6, IL‐1β and IL‐23 synergized, are still perplexing. Notably, TGFβRI ablation, but not TGF‐β antibody blockade, dramatically reduced the proportion of Th17 cells from 30% to 13%.46 This suggests that TGFβRI signalling at least partially contributes to Th17 differentiation under this cytokine regimen. It is very likely that there is TGFβRI ligand produced, which enhances the Th17 programme in an autocrine pattern under these in vitro culture conditions. Further studies should especially focus on TGF‐β superfamily cytokines that can be secreted by these Th17 cells and also can signal through TGFβRI. For those Th17 cells deficient in TGFβRI, it is also possible that they are primed by the combination of cytokines, and then secondarily induced by autocrine cytokines through other TGF‐β superfamily receptors except TGFβRI. Further studies are warranted to uncover the requirements and central mechanisms of TGF‐β signalling in Th17 differentiation.

Mechanisms underlying TGF‐β promoted Th17 differentiation

Transforming growth factor‐β induces naive T cells to express the regulatory transcription factor Foxp3 upon T‐cell receptor activation.79 Foxp3 can directly interact with RORγt and antagonize the Th17 master regulator RORγt.80, 81, 82 Although IL‐6 can activate STAT3 and inhibit Foxp3 expression,8 it cannot sufficiently induce the RORγt transcriptional programme. TGF‐β is required for the full differentiation capacity of Th17 cells. Confounded by these observations, extensive studies have been performed to explain the paradoxical role of TGF‐β in Th17 differentiation in the last decade (Fig. 2).

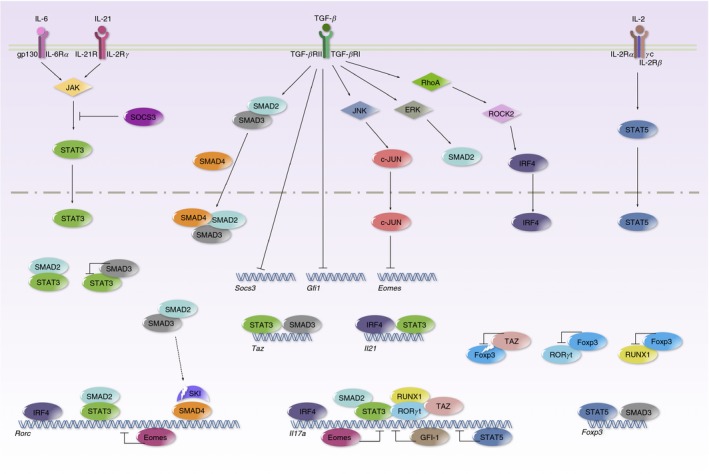

Figure 2.

Transforming growth factor‐β (TGF‐β) promotes T helper 17 (Th17) differentiation through multiple mechanisms. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), induced by interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) or IL‐21, potentiates the Th17‐related transcriptional programme by binding to Rorc, Il17a, and Il21 loci. TGF‐β receptor signalling phosphorylates SMAD2 and SMAD3. The SMAD2/3 complex interacts with SMAD4 and translocates into the nucleus. Meanwhile, SMAD2 and SMAD3 act as a co‐activator and co‐repressor of STAT3, and oppositely modify STAT3‐induced transcription. TGF‐β signalling triggers SKI degradation to unleash SMAD4 and SKI complex repressed ROR γt expression. TGF‐β suppresses SOCS3 to prolong STAT3 activation. TGF‐β suppresses GFI‐1 to promote Il17a transcription. TGF‐β suppresses Eomes through the JNK‐c–JUN pathway to enhance Rorc and Il17a transcription. TGF‐β drives RhoA‐ROCK2 to phosphorylate IRF4 and to up‐regulate the expression of ROR γt, IL‐17 and IL‐21. TGF‐β induces TAZ to co‐activate ROR γt and to reduce Foxp3 through proteasomal degradation.

Essential transcription factors in Th17 differentiation

T helper 17 differentiation is controlled by several key transcription factors.83 The Th17 lineage‐specific regulator RORγt (encoded by Rorc gene) directs IL‐17 production by binding to the IL‐17 gene locus.3, 81 RORγt‐deficient T cells fail to become Th17 cells; reducing the transcriptional activity of RORγt by antagonists such as digoxin effectively inhibits Th17 differentiation.84 Post‐translational regulation of RORγt by small‐molecule RORγt antagonists,85 or by ubiquitin ligase UBR5 in response to TGF‐β signalling can limit the abundance of RORγt and so prevent rampant IL‐17 production.86

STAT3 regulates the transcription of its multiple target genes, including Rorc, Il17a and Il17f. STAT3 is required for Th17 differentiation and its deficiency results in abrogated Th17 generation, whereas overexpression of STAT3 significantly boosts Th17 differentiation.14, 87, 88, 89

The cooperative binding of basic leucine zipper transcription factor, ATF‐like (BATF) and IRF4 is critical for initial chromatin accessibility and combinatorial regulation with STAT3 during Th17 differentiation.83, 90 Either IRF4 or BATF ablation results in failure of RORγt induction and defective Th17 differentiation.91, 92, 93

SMAD‐dependent pathways

The canonical TGF‐β pathway signals through the TGF‐β receptor and phosphorylates receptor‐regulated SMADs (R‐SMAD), SMAD2 and SMAD3. The heterodimeric complex then interacts with the common mediator SMAD (co‐SMAD), SMAD4, to generate a heterotrimeric complex. This new complex translocates into the nucleus for downstream gene modulation. Complementarily, TGF‐β can activate non‐canonical pathways such as phosphoinositide 3 kinase/AKT/ mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways (extracellular signal‐regulated kinase, Jun N‐terminal kinase and p38 MAPK), and nuclear factor‐κB pathways for T‐cell function.94, 95, 96

SMAD2‐deficient T cells have reduced ability for Th17 differentiation.57, 97 SMAD2 may modulate IL‐6R expression and STAT3 activation in the presence of TGF‐β.39 Another study found that SMAD2 binds to and synergizes with RORγt and positively regulates Th17 differentiation.57

SMAD3 appears to act in opposition to SMAD2. Deficiency of SMAD3 leads to enhanced Th17 differentiation both in vitro and in vivo.98 SMAD3 is also found to bind directly to RORγt, and inhibits RORγt transcriptional activity.

There is also an argument that neither SMAD2 nor SMAD3 is essential for Th17 differentiation. In one report, no defect in Th17 differentiation in either SMAD2‐ or SMAD3‐deficient mice was observed, whereas the non‐canonical MAPK pathway was implicated.99 In another report, Th17 differentiation in SMAD2‐deficient mice was reduced, but remained intact in SMAD3‐deficient mice, and was abolished in SMAD2 and SMAD3 double knockout mice.100 The deficiency of SMAD2 and SMAD3 did not alter Rorc gene expression but increased the level of the inhibitory cytokine, IL‐2.101 In the presence of IL‐2 blocking antibody, CD4+ T cells carrying SMAD2/3 double knockout restored half of the efficiency to differentiate into Th17 cells. These results suggest that SMAD2 and SMAD3 are partially and redundantly required for Th17 differentiation. A recent report supports the idea that SMAD2 plays a positive role, whereas SMAD3 plays a negative role in regulating Th17 differentiation.102 SMAD2 serves as a co‐activator, and SMAD3 serves as a co‐repressor in interactions with STAT3 to modulate Rorc and Il17a gene expression under the context of TGF‐β determined phosphorylation status.

These conflicting results regarding SMAD2‐ or SMAD3‐deficient mice among different studies appear confusing. This could be due to differences between wild‐type control cells and knockout cells that were compromised under certain in vitro culture conditions or treatments, including TGF‐β dose. Different doses of TGF‐β result in different R‐SMAD phosphorylation dynamics,103 and different efficiencies in Th17 induction.4 Nonetheless, all these studies acknowledge the involvement of the canonical TGF‐β pathway in Th17 differentiation.

SMAD4 is recognized as a canonical TGF‐β signalling central component. So it is reasonable to predict a TGF‐β signalling defect after deletion of SMAD4. Indeed, TGF‐β‐induced Foxp3+ Treg cell differentiation is impaired in SMAD4‐deficient mice. Astonishingly, however, Th17 differentiation is unaffected by the loss of SMAD4 under Th17 polarizing conditions.104 This observation was confirmed later by another study.105 Therefore, it appears that SMAD4 is not required for Th17 differentiation, and that TGF‐β induces Th17 differentiation through an SMAD4‐independent mechanism. However, in later studies, SMAD4 deletion counterbalances the severe autoimmunity caused by the loss of TGF‐β receptor II signalling, suggesting that SMAD4 could regulate T‐cell function on its own in the absence of TGF‐β receptor signalling.106 Inspired by the notion, Zhang et al.58 fortuitously found that SMAD4‐deficient naive T cells efficiently differentiated into Th17 cells when provided with IL‐6 alone in the absence of TGF‐β signalling. Although TGF‐β receptor II mice were unable to generate Th17 cells in the spinal cord and were protected from EAE, the additional deletion of SMAD4 fully restored Th17 differentiation as well as encephalomyelitis. These data suggest that SMAD4 is playing a decisive role in licensing Th17 differentiation. A series of experiments demonstrate that SMAD4 and repressor SKI interact and cooperatively suppress Th17 differentiation primarily through direct binding to multiple loci of Rorc. SMAD4 itself does not possess the suppressive activity but it is required for recruiting SKI to specific chromatin loci. The suppression effect can be offset in the presence of TGF‐β through TGF‐β‐directed degradation of SKI. These observations provide novel mechanistic insight into TGF‐β‐dependent Th17 differentiation. CD4+ T cells with CRISPR/Cas9‐disrupted SKI can differentiate into Th17 cells without the need for TGF‐β signalling. This suggests one important function for TGF‐β in Th17 differentiation is to degrade SKI. Further studies on SKI conditional knockout mice would be helpful to elaborate on the mechanistic details. Importantly, a single amino acid substitution, which released SKI from SMAD4 interactions and caused unchecked Th17 differentiation, mutually affirms the importance of losing SKI interactions in generating Th17 cells. Also, Ong et al.107 found that the absence of SKI in CD4+ T cells led to increased Th17 differentiation at low levels of TGF‐β. Indeed, low doses of TGF‐β can effectively degrade SKI and the degradation efficiency correlated with the induction efficiency of Th17 differentiation.58 The SKI/SMAD4 complex is highlighted as a switch for Th17 differentiation, and it might be also helpful to explain the generation of pathogenic Th17 cells by TGF‐β‐independent cytokines.46

Many questions remain for further mechanistic details, such as: why SMAD4 and SKI primarily suppress the Rorc gene but not other genes? Is it possible that SMAD4 affects the genome accessibility on the Rorc locus? Is the binding on the Rorc locus constitutive or dependent upon specific T‐cell receptor or cytokine stimulation? As SKI could serve as a potential therapeutic target for many diseases,108 it would be important to investigate how SKI is degraded by TGF‐β signalling in T cells. SMAD2 and SMAD3 were reported to mediate the ubiquitination and degradation of SKI,109 which may explain their partial requirement in T cells.58 However, TGF‐β signalling does not always trigger SKI degradation in all cell types.110 These questions must be addressed in future investigations.

SMAD‐independent pathways

In addition to SMADs, there are several studies that offer insights from non‐SMAD pathways to explain the role of TGF‐β in promoting Th17 differentiation.

It has been well known that both Th1 and Th2 cytokines potently inhibit Th17 differentiation.1, 2 TGF‐β is capable of inhibiting Th1 and Th2 differentiation through their lineage transcription factors T‐bet and GATA3.29, 111, 112 TGF‐β may exert its function by preventing Th1 and Th2 programmes to enhance Th17 differentiation. In T‐bet and STAT6 double‐deficient T cells, IL‐6 alone is sufficient to induce Th17 differentiation.77, 78 These results clearly showed that one of the mechanisms for TGF‐β in promoting Th17 differentiation is to negatively regulate Th1 and Th2 programmes. Currently, it is not clear whether the double deficiency of T‐bet and STAT6 can produce similar results in C57BL/6 mice as in these BALB/c mice. Notably, in these double knockout T cells, the addition of either TGF‐β or anti‐TGF‐β antibody had no effect on IL‐17 production in one report,78 but had around four times the promotion or reduction effect on IL‐17 production in another report.77 This discrepancy and genetic background difference obscure the interpretation of how exactly TGF‐β plays the role in Th17 differentiation. As SKI/SMAD4 also functions as a suppressor of RORγt expression, and SMAD4‐deficient T cells also can differentiate into Th17 cells with IL‐6 alone, it is not clear whether these two mechanisms are required for each other. For example, whether T‐bet and STAT6 double‐deficient T cells have disrupted SMAD4 or SKI function. STAT6 downstream target GATA3 was also reported to control TGF‐β‐induced Foxp3, suggesting possible cross talk between Th1/Th2 and the downstream of TGF‐β pathways.113, 114

Interleukin‐6‐induced suppressor of cytokine signalling 3 (SOCS3) is a negative feedback regulator of STAT3, and TGF‐β can suppress the transcription of SOCS3.115 Small interfering RNA knockdown of SOCS3 promotes Rorc expression and in vitro Th17 differentiation in the presence or absence of TGF‐β. These data indicate that TGF‐β suppresses SOCS3 to prolong STAT3 activation and to promote Th17 generation.

Under Th17 skewing conditions, protein kinase ROCK2 phosphorylated IRF4 to up‐regulate the expression of RORγt, IL‐17 and IL‐21. The TGF‐β is required to drive the activation of RhoA/ROCK2 to promote Th17 differentiation.116

To identify the SMAD‐independent mechanisms underlying TGF‐β in Th17 cells, Ichiyama et al.117 used SMAD2 and SMAD3 double‐deficient mice and identified the transcription factor Eomesodermin (Eomes), which directly binds to the Rorc and Il17a promoter region controlling Th17 differentiation. Ablation of Eomes expression by short hairpin RNA led to the induction of Th17 cells in the absence of TGF‐β, while overexpression of Eomes substantially constrained Th17 differentiation.117, 118 Eomes is subjected to the suppression of TGF‐β signalling through Jun N‐terminal kinase‐c‐Jun pathway, which provides an important mechanism for SMAD‐independent Th17 cell differentiation.

In summary, these SMAD‐dependent and SMAD‐independent pathways prove that TGF‐β induces Th17 differentiation not through a single pathway but rather that multiple mechanisms are involved to achieve efficient Th17 differentiation.

In recent years, there has been an increased understanding of environmental cues shaping the Th17 differentiation.119, 120, 121 For example, serum glucocorticoid kinase 1 (SGK1) can be up‐regulated by sensing the NaCl in a high‐salt diet through phosphorylation of p38 MAPK, which promotes IL‐23R expression, induces pathogenic Th17 cells, and exacerbates murine EAE.122, 123 As TGF‐β 1 is able to stimulate the SGK1 expression, and SGK1 is highly specifically expressed under Th17 conditions,122 it could be another explanation for TGF‐β‐induced Th17 differentiation. Although there have been arguments regarding the physiological underpinnings of this model,124, 125, 126 these data provide a novel target for drug development and methods for the treatment of autoimmune diseases.

Although there are possibly more unrevealed TGF‐β signalling pathways for promoting Th17 differentiation, further studies will help to elucidate the precise mechanism of Th17 differentiation, as well as the pathogenicity of Th17 cells. Also, investigating the prominent pathways under different pathological conditions and environmental cues would be helpful for the intervention in Th17 differentiation to protect health.

TGF‐β signalling in Th17 cells plasticity

In addition to Th17 cells, naive T cells can differentiate into several types of helper T cells (Fig. 3). Increasing evidence has implicated the plasticity of T‐cell subsets.127 As TGF‐β is essential for the development of both Th17 and Foxp3+ Treg cells, the TGF‐β signalling pathway provides a dichotomous role and intimate link between Th17 and Foxp3+ Treg cells.128, 129 TGF‐β can induce Foxp3 expression, whereas the presence of IL‐6 or IL‐21 can prevent the conversion of Th17 to Foxp3+ Treg cells and promotes Th17 lineage commitment.8, 11, 12

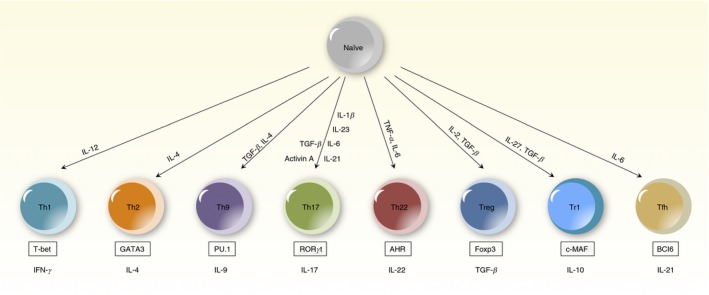

Figure 3.

T helper differentiation. Diagram of T helper differentiation pathways for T helper 1 (Th1), Th2, Th9, Th17, Th22, regulatory T (Treg), regulatory T type 1 (Tr1) and T follicular helper (Tfh) cells. Cytokines that play an important role in inducing CD4+ T‐cell differentiation are listed above the cell types, and cell‐specific transcription factors are listed in a box below the cell types.

The reciprocal differentiation of Th17 cells and Foxp3+ Treg cells is involved in multiple immune mechanisms. TGF‐β signalling plays a critical role in the fate decision between Th17 and Foxp3+ Treg cells. For example, TGF‐β‐induced Foxp3+ Treg cells promote Th17 development through IL‐2 regulation.101, 130, 131 Mice deficient in tumour necrosis factor receptor‐associated factor 6 have less IL‐2 and therefore have promoted Th17 cell differentiation.132 In another study, TGF‐β down‐regulates the expression of a transcriptional repressor, Growth Factor Independent 1 (GFI‐1), which associates with histone lysine‐specific demethylase 1 to directly bind the intergenic region of Il17a/Il17f loci, and so represses IL‐17 expression.49 Another example in which TGF‐β regulates the Th17 and Foxp3+ Treg cell response is the TGF‐β‐induced Tafazzin (TAZ). TAZ is a co‐activator of RORγt, and decreases acetylation of Foxp3 to regulate the reciprocal balance between Th17 and Foxp3+ Treg cells.133 In addition, TGF‐β‐induced death‐associated protein kinase promotes the proteasomal degradation of hypoxia‐inducible factor 1 (HIF‐1), a key metabolic sensor,134 to regulate the balance of Th17 and Foxp3+ Treg cells, which ultimately prevents Th17‐mediated pathology in autoimmunity.135 In another model, TGF‐β promoted the colon‐specific trafficking molecule G Protein‐Coupled Receptor 15 (GPR15), which inhibits G Protein‐Coupled Receptor 174 (GPR174) on Foxp3+ Treg cells, and supports the accumulation and retention of Foxp3+ Treg cells in the colon to dampen Th17 responses.136 Finally, TGF‐β triggers the degradation of the newly identified T‐cell player SKI, and promotes Th17 differentiation.58 However, the deletion of SKI in Foxp3+ T cells also leads to increased Foxp3+ Treg cell conversion.107 These observations suggest that residual amounts of SKI may exist and play an important role in Foxp3+ Treg cells, possibly balancing the differentiation of Th17 and Foxp3+ Treg cells. Further study on the detailed role of SKI could be beneficial for the understanding of Th17 and Foxp3+ Treg cell reciprocal differentiation.

T helper 17 cells can also transdifferentiate into another Treg cell subset, type 1 regulatory T cells (Tr1) to halt inflammation.137, 138 Besides, TGF‐β converts Th1 cells into Th17 cells through the induction of RUNX1 expression.139 Conversely, Th1 lineage‐specific transcription factor T‐bet can repress RUNX1‐mediated RORγt transactivation to prevent Th17 differentiation.140 TGF‐β is required for human memory Th17 cells to produce Th9 cell cytokine, IL‐9.141 Moreover, murine Th17 cells in Peyer's patches can convert to the T follicular helper cells (Tfh) phenotype,142 possibly because TGF‐β is critical for providing additional signals for STAT3 and STAT4 to promote human Tfh differentiation.143

Currently, it is unclear if all T helper subsets have the potential to convert to each other under specific circumstances. Although Th17, Foxp3+ Treg, Tr1, Th9 and Tfh cells are distinct subsets, all of them can be promoted by TGF‐β.138 It is possible that these subsets share similar key factors associated with the TGF‐β signalling pathway, and the factors may be targeted as a switch in balancing autoimmunity and self‐tolerance. Hence it is important to investigate the underlying mechanisms and identify the key factors in the TGF‐β‐directed T helper programming network.

The importance of metabolic control in T‐cell function and plasticity has gained more and more attention in recent years.144, 145, 146, 147 The mTOR forms two structurally and functionally distinct complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2; mTOR senses diverse environmental cues such as growth factors, oxygen, nutrients, energy and stress, and integrates into protein synthesis, lipid, nucleotide and glucose metabolism.148 Loss of mTORC1 results in failure of Th17 differentiation, whereas mTORC2 deficiency does not affect Th1 or Th17 differentiation.149, 150 Interestingly, if both mTORC1 and mTORC2 are inhibited, T cells skew toward Foxp3+ Treg cell differentiation. Although it remains unclear whether TGF‐β plays a pivotal role in regulating the mTOR pathway under pathological conditions, the cross talk between TGF‐β and mTOR signalling is certainly worthy of investigation. For example, mTORC2 could modulate SMAD2/3 linker phosphorylation to regulate TGF‐β or activin signalling.151

The mTOR is required for the induction of HIF1α, a key regulator mediating T‐cell glycolytic activity.152 HIF1α controls the T‐cell fate decision between Th17 and Foxp3+ Treg cells. HIF1α deficiency alters the dichotomy between these two T‐cell lineages by diminishing Th17 and promoting Foxp3+ Treg cell differentiation.134, 152 In vitro experiments shows that TGF‐β has the ability to induce the expression of HIF1α.134, 153 However, the proportion and importance of TGF‐β‐contributed induction of HIF1α in vivo is currently unknown.

Myc is another important target of mTOR. Myc controls glycolysis and glutaminolysis. It is required for metabolic reprogramming upon T‐cell activation.154 The fact that Myc could be repressed by TGF‐β,155, 156, 157 suggests a possible link between TGF‐β and T‐cell metabolism.

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) responds to environmental toxins and metabolites. It boosts either Th17 or Foxp3+ Treg cell differentiation in a ligand‐specific fashion.158, 159 Although AHR‐deficient T cells could differentiate into Th17 cells, they fail to produce the Th17 cytokine, IL‐22.159 AHR is highly expressed in Th17 cells and Tr1 cells,160 but not Treg cells.158, 159 AHR expression is positively correlated with TGF‐β concentration in the presence of IL‐6, but is not required for IL‐22 production in the absence of TGF‐β.161 TGF‐β suppresses IL‐22 production in Th17 cells through c‐Maf but not AHR.161 There are also studies suggesting that the regulation of AHR by TGF‐β appears to be cell‐type specific.162, 163, 164 These paradoxes warrant further investigation on the role of TGF‐β in AHR modulation.

These metabolic checkpoints and pathways orchestrate the balance between Th17 cells and other subsets.165, 166, 167 The understanding of Th17 plasticity may provide tools for immunotherapies of autoimmune disease.168, 169 However, there are significant gaps between the TGF‐β signalling and T‐cell metabolic control. Therefore, it is important to investigate how TGF‐β shapes and affects metabolic reprogramming in T cells.

Concluding remarks and featured questions

The unravelling of the key factors and pathways responsible for both TGF‐β‐dependent and TGF‐β‐independent Th17 differentiation is essential for understanding the development, pathogenicity and plasticity of Th17 cells. With more understanding of the mechanisms underlying TGF‐β‐promoted Th17 differentiation in the future, the following questions should be addressed:

What are the dominant cytokine sources for tissue‐resident Th17 and pathogenic Th17 cells in different tissues or organs during health and disease conditions?

Is the dysregulation of TGF‐β or TGF‐β signalling responsible for the Th17 cells that have gone rogue?

How is Th17 differentiation regulated by various cytokine regimens? Does the SKI/SMAD4 complex play a role in other cytokine signalling pathways besides IL‐6 plus TGF‐β 1?

Are there any other unknown key transcriptional suppressors or activators of RORγt that also respond to TGF‐β?

How exactly is the pathogenicity of Th17 cells regulated? What are the functions of TGF‐β signalling in pathogenic Th17 cells? Does the TGF‐β–SKI–SMAD4 axis play a role in the generation of pathogenic Th17 cells?

Are there specific markers and functional differences to distinguish initially committed and subsequently converted Th17 cells?

Within the context of autoimmune disease, is it appropriate to always assume Treg cells as friends while considering Th17 cells as foes? Do these cells work together during the initiation or progression phase of the disease?

Do all T helper cell subsets have the plastic potential to become any other subset? Is it possible to develop a drug to convert some, if not all, of the different subsets into one subset simultaneously?

Is TGF‐β or TGF‐β signalling involved in the metabolic control of T‐cell function?

Further comprehensive studies on the role of TGF‐β in controlling Th17 differentiation and function will allow us to gain insights on how Th17 differentiation impacts immune homeostasis under physiological context and facilitates the development of therapeutic intervention methods for inflammatory and autoimmune diseases.

Disclosures

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Seddon Y. Thomas for critical reading and editing of the manuscript, and thanks the support of State Key Laboratory of Medicinal Chemical Biology.

References

- 1. Harrington LE, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, Turner H, Murphy TL, Murphy KM et al Interleukin 17‐producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nat Immunol 2005; 6:1123–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Park H, Li Z, Yang XO, Chang SH, Nurieva R, Wang YH et al A distinct lineage of CD4 T cells regulates tissue inflammation by producing interleukin 17. Nat Immunol 2005; 6:1133–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, Tadokoro CE, Lepelley A, Lafaille JJ et al The orphan nuclear receptor RORγt directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL‐17+ T helper cells. Cell 2006; 126:1121–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL‐17 and Th17 cells. Annu Rev Immunol 2009; 27:485–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tesmer LA, Lundy SK, Sarkar S, Fox DA. Th17 cells in human disease. Immunol Rev 2008; 223:87–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stockinger B, Omenetti S. The dichotomous nature of T helper 17 cells. Nat Rev Immunol 2017; 17:535–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Patel DD, Kuchroo VK. Th17 cell pathway in human immunity: lessons from genetics and therapeutic interventions. Immunity 2015; 43:1040–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M et al Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature 2006; 441:235–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, Locksley RM, Stockinger B. TGFβ in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL‐17‐producing T cells. Immunity 2006; 24:179–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heink S, Yogev N, Garbers C, Herwerth M, Aly L, Gasperi C et al Trans‐presentation of IL‐6 by dendritic cells is required for the priming of pathogenic TH17 cells. Nat Immunol 2017; 18:74–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Korn T, Bettelli E, Gao W, Awasthi A, Jager A, Strom TB et al IL‐21 initiates an alternative pathway to induce proinflammatory TH17 cells. Nature 2007; 448:484–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nurieva R, Yang XO, Martinez G, Zhang Y, Panopoulos AD, Ma L et al Essential autocrine regulation by IL‐21 in the generation of inflammatory T cells. Nature 2007; 448:480–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhou L, Ivanov II, Spolski R, Min R, Shenderov K, Egawa T et al IL‐6 programs TH‐17 cell differentiation by promoting sequential engagement of the IL‐21 and IL‐23 pathways. Nat Immunol 2007; 8:967–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wei L, Laurence A, Elias KM, O'Shea JJ. IL‐21 is produced by Th17 cells and drives IL‐17 production in a STAT3‐dependent manner. J Biol Chem 2007; 282:34605–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sutton C, Brereton C, Keogh B, Mills KH, Lavelle EC. A crucial role for interleukin (IL)‐1 in the induction of IL‐17‐producing T cells that mediate autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med 2006; 203:1685–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chung Y, Chang SH, Martinez GJ, Yang XO, Nurieva R, Kang HS et al Critical regulation of early Th17 cell differentiation by interleukin‐1 signaling. Immunity 2009; 30:576–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mufazalov IA, Schelmbauer C, Regen T, Kuschmann J, Wanke F, Gabriel LA et al IL‐1 signaling is critical for expansion but not generation of autoreactive GM‐CSF+ Th17 cells. EMBO J 2017; 36:102–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ikeda S, Saijo S, Murayama MA, Shimizu K, Akitsu A, Iwakura Y. Excess IL‐1 signaling enhances the development of Th17 cells by downregulating TGF‐β‐induced Foxp3 expression. J Immunol 2014; 192:1449–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stritesky GL, Yeh N, Kaplan MH. IL‐23 promotes maintenance but not commitment to the Th17 lineage. J Immunol 2008; 181:5948–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McGeachy MJ, Bak‐Jensen KS, Chen Y, Tato CM, Blumenschein W, McClanahan T et al TGF‐β and IL‐6 drive the production of IL‐17 and IL‐10 by T cells and restrain TH‐17 cell‐mediated pathology. Nat Immunol 2007; 8:1390–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee Y, Awasthi A, Yosef N, Quintana FJ, Xiao S, Peters A et al Induction and molecular signature of pathogenic TH17 cells. Nat Immunol 2012; 13:991–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Travis MA, Sheppard D. TGF‐β activation and function in immunity. Annu Rev Immunol 2014; 32:51–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen W, Ten Dijke P. Immunoregulation by members of the TGFβ superfamily. Nat Rev Immunol 2016; 16:723–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Boor P, Ostendorf T, Floege J. Renal fibrosis: novel insights into mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Nephrol 2010; 6:643–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shi M, Zhu J, Wang R, Chen X, Mi L, Walz T et al Latent TGF‐β structure and activation. Nature 2011; 474:343–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Travis MA, Reizis B, Melton AC, Masteller E, Tang Q, Proctor JM et al Loss of integrin α v β 8 on dendritic cells causes autoimmunity and colitis in mice. Nature 2007; 449:361–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yoshida Y, Yoshimi R, Yoshii H, Kim D, Dey A, Xiong H et al The transcription factor IRF8 activates integrin‐mediated TGF‐β signaling and promotes neuroinflammation. Immunity 2014; 40:187–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mangan PR, Harrington LE, O'Quinn DB, Helms WS, Bullard DC, Elson CO et al Transforming growth factor‐β induces development of the TH17 lineage. Nature 2006; 441:231–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li MO, Wan YY, Flavell RA. T cell‐produced transforming growth factor‐β1 controls T cell tolerance and regulates Th1‐ and Th17‐cell differentiation. Immunity 2007; 26:579–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Flavell RA, Stockinger B. Signals mediated by transforming growth factor‐β initiate autoimmune encephalomyelitis, but chronic inflammation is needed to sustain disease. Nat Immunol 2006; 7:1151–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Acosta‐Rodriguez EV, Napolitani G, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Interleukins 1β and 6 but not transforming growth factor‐β are essential for the differentiation of interleukin 17‐producing human T helper cells. Nat Immunol 2007; 8:942–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wilson NJ, Boniface K, Chan JR, McKenzie BS, Blumenschein WM, Mattson JD et al Development, cytokine profile and function of human interleukin 17‐producing helper T cells. Nat Immunol 2007; 8:950–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. van den Broek T, Borghans JAM, van Wijk F. The full spectrum of human naive T cells. Nat Rev Immunol 2018; doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0001-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Manel N, Unutmaz D, Littman DR. The differentiation of human TH‐17 cells requires transforming growth factor‐β and induction of the nuclear receptor RORγt. Nat Immunol 2008; 9:641–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Volpe E, Servant N, Zollinger R, Bogiatzi SI, Hupe P, Barillot E et al A critical function for transforming growth factor‐β, interleukin 23 and proinflammatory cytokines in driving and modulating human TH‐17 responses. Nat Immunol 2008; 9:650–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yang L, Anderson DE, Baecher‐Allan C, Hastings WD, Bettelli E, Oukka M et al IL‐21 and TGF‐β are required for differentiation of human TH17 cells. Nature 2008; 454:350–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cosmi L, De Palma R, Santarlasci V, Maggi L, Capone M, Frosali F et al Human interleukin 17‐producing cells originate from a CD161+CD4+ T cell precursor. J Exp Med 2008; 205:1903–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Maggi L, Santarlasci V, Capone M, Peired A, Frosali F, Crome SQ et al CD161 is a marker of all human IL‐17‐producing T‐cell subsets and is induced by RORC. Eur J Immunol 2010; 40:2174–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Santarlasci V, Maggi L, Capone M, Frosali F, Querci V, De Palma R et al TGF‐β indirectly favors the development of human Th17 cells by inhibiting Th1 cells. Eur J Immunol 2009; 39:207–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Takahashi T, Dejbakhsh‐Jones S, Strober S. Expression of CD161 (NKR‐P1A) defines subsets of human CD4 and CD8 T cells with different functional activities. J Immunol 2006; 176:211–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fujio K, Komai T, Inoue M, Morita K, Okamura T, Yamamoto K. Revisiting the regulatory roles of the TGF‐β family of cytokines. Autoimmun Rev 2016; 15:917–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yang Y, Weiner J, Liu Y, Smith AJ, Huss DJ, Winger R et al T‐bet is essential for encephalitogenicity of both Th1 and Th17 cells. J Exp Med 2009; 206:1549–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Huss DJ, Winger RC, Peng H, Yang Y, Racke MK, Lovett‐Racke AE. TGF‐β enhances effector Th1 cell activation but promotes self‐regulation via IL‐10. J Immunol 2010; 184:5628–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lee PW, Yang Y, Racke MK, Lovett‐Racke AE. Analysis of TGF‐β1 and TGF‐β3 as regulators of encephalitogenic Th17 cells: implications for multiple sclerosis. Brain Behav Immun 2015; 46:44–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gutcher I, Donkor MK, Ma Q, Rudensky AY, Flavell RA, Li MO. Autocrine transforming growth factor‐β1 promotes in vivo Th17 cell differentiation. Immunity 2011; 34:396–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, Yang XP, Tato CM, McGeachy MJ, Konkel JE et al Generation of pathogenic TH17 cells in the absence of TGF‐β signalling. Nature 2010; 467:967–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Suffia IJ, Reckling SK, Piccirillo CA, Goldszmid RS, Belkaid Y. Infected site‐restricted Foxp3+ natural regulatory T cells are specific for microbial antigens. J Exp Med 2006; 203:777–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Stephens GL, Andersson J, Shevach EM. Distinct subsets of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells participate in the control of immune responses. J Immunol 2007; 178:6901–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhu J, Davidson TS, Wei G, Jankovic D, Cui K, Schones DE et al Down‐regulation of Gfi‐1 expression by TGF‐β is important for differentiation of Th17 and CD103+ inducible regulatory T cells. J Exp Med 2009; 206:329–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hu W, Troutman TD, Edukulla R, Pasare C. Priming microenvironments dictate cytokine requirements for T helper 17 cell lineage commitment. Immunity 2011; 35:1010–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fernandez S, Molina IJ, Romero P, Gonzalez R, Pena J, Sanchez F et al Characterization of gliadin‐specific Th17 cells from the mucosa of celiac disease patients. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106:528–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Coombes JL, Siddiqui KR, Arancibia‐Carcamo CV, Hall J, Sun CM, Belkaid Y et al A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF‐β and retinoic acid‐dependent mechanism. J Exp Med 2007; 204:1757–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Paidassi H, Acharya M, Zhang A, Mukhopadhyay S, Kwon M, Chow C et al Preferential expression of integrin α v β 8 promotes generation of regulatory T cells by mouse CD103+ dendritic cells. Gastroenterology 2011; 141:1813–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Worthington JJ, Czajkowska BI, Melton AC, Travis MA. Intestinal dendritic cells specialize to activate transforming growth factor‐β and induce Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via integrin α v β 8 . Gastroenterology 2011; 141:1802–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wakefield LM, Letterio JJ, Chen T, Danielpour D, Allison RS, Pai LH et al Transforming growth factor‐β1 circulates in normal human plasma and is unchanged in advanced metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 1995; 1:129–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chikuma S, Suita N, Okazaki IM, Shibayama S, Honjo T. TRIM28 prevents autoinflammatory T cell development in vivo . Nat Immunol 2012; 13:596–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Malhotra N, Robertson E, Kang J. SMAD2 is essential for TGF‐β‐mediated Th17 cell generation. J Biol Chem 2010; 285:29044–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zhang S, Takaku M, Zou L, Gu AD, Chou WC, Zhang G et al Reversing SKI‐SMAD4‐mediated suppression is essential for TH17 cell differentiation. Nature 2017; 551:105–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rodgarkia‐Dara C, Vejda S, Erlach N, Losert A, Bursch W, Berger W et al The activin axis in liver biology and disease. Mutat Res 2006; 613:123–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Huber S, Stahl FR, Schrader J, Luth S, Presser K, Carambia A et al Activin a promotes the TGF‐β‐induced conversion of CD4+CD25− T cells into Foxp3+ induced regulatory T cells. J Immunol 2009; 182:4633–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hohlfeld R, Dornmair K, Meinl E, Wekerle H. The search for the target antigens of multiple sclerosis, part 1: autoreactive CD4+ T lymphocytes as pathogenic effectors and therapeutic targets. Lancet Neurol 2016; 15:198–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Langrish CL, Chen Y, Blumenschein WM, Mattson J, Basham B, Sedgwick JD et al IL‐23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med 2005; 201:233–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Uyttenhove C, Van Snick J. Development of an anti‐IL‐17A auto‐vaccine that prevents experimental auto‐immune encephalomyelitis. Eur J Immunol 2006; 36:2868–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Gonzalez‐Garcia I, Zhao Y, Ju S, Gu Q, Liu L, Kolls JK et al IL‐17 signaling‐independent central nervous system autoimmunity is negatively regulated by TGF‐β . J Immunol 2009; 182:2665–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Komiyama Y, Nakae S, Matsuki T, Nambu A, Ishigame H, Kakuta S et al IL‐17 plays an important role in the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol 2006; 177:566–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Haak S, Croxford AL, Kreymborg K, Heppner FL, Pouly S, Becher B et al IL‐17A and IL‐17F do not contribute vitally to autoimmune neuro‐inflammation in mice. J Clin Invest 2009; 119:61–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Eugster HP, Frei K, Kopf M, Lassmann H, Fontana A. IL‐6‐deficient mice resist myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein‐induced autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Eur J Immunol 1998; 28:2178–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Samoilova EB, Horton JL, Hilliard B, Liu TS, Chen Y. IL‐6‐deficient mice are resistant to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: roles of IL‐6 in the activation and differentiation of autoreactive T cells. J Immunol 1998; 161:6480–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Cua DJ, Sherlock J, Chen Y, Murphy CA, Joyce B, Seymour B et al Interleukin‐23 rather than interleukin‐12 is the critical cytokine for autoimmune inflammation of the brain. Nature 2003; 421:744–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Awasthi A, Riol‐Blanco L, Jager A, Korn T, Pot C, Galileos G et al Cutting edge: IL‐23 receptor gfp reporter mice reveal distinct populations of IL‐17‐producing cells. J Immunol 2009; 182:5904–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. McGeachy MJ, Chen Y, Tato CM, Laurence A, Joyce‐Shaikh B, Blumenschein WM et al The interleukin 23 receptor is essential for the terminal differentiation of interleukin 17‐producing effector T helper cells in vivo . Nat Immunol 2009; 10:314–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. McQualter JL, Darwiche R, Ewing C, Onuki M, Kay TW, Hamilton JA et al Granulocyte macrophage colony‐stimulating factor: a new putative therapeutic target in multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med 2001; 194:873–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Codarri L, Gyulveszi G, Tosevski V, Hesske L, Fontana A, Magnenat L et al RORγt drives production of the cytokine GM‐CSF in helper T cells, which is essential for the effector phase of autoimmune neuroinflammation. Nat Immunol 2011; 12:560–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. El‐Behi M, Ciric B, Dai H, Yan Y, Cullimore M, Safavi F et al The encephalitogenicity of TH17 cells is dependent on IL‐1‐ and IL‐23‐induced production of the cytokine GM‐CSF. Nat Immunol 2011; 12:568–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Croxford AL, Lanzinger M, Hartmann FJ, Schreiner B, Mair F, Pelczar P et al The cytokine GM‐CSF drives the inflammatory signature of CCR2+ monocytes and licenses autoimmunity. Immunity 2015; 43:502–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kanellopoulou C, Muljo SA. Fine‐tuning Th17 cells: to be or not to be pathogenic? Immunity 2016; 44:1241–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Yang Y, Xu J, Niu Y, Bromberg JS, Ding Y. T‐bet and eomesodermin play critical roles in directing T cell differentiation to Th1 versus Th17. J Immunol 2008; 181:8700–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Das J, Ren G, Zhang L, Roberts AI, Zhao X, Bothwell AL et al Transforming growth factor β is dispensable for the molecular orchestration of Th17 cell differentiation. J Exp Med 2009; 206:2407–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Chen W, Jin W, Hardegen N, Lei KJ, Li L, Marinos N et al Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25− naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF‐β induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J Exp Med 2003; 198:1875–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Zhou L, Lopes JE, Chong MM, Ivanov II, Min R, Victora GD et al TGF‐β‐induced Foxp3 inhibits TH17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORγt function. Nature 2008; 453:236–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ichiyama K, Yoshida H, Wakabayashi Y, Chinen T, Saeki K, Nakaya M et al Foxp3 inhibits RORγt‐mediated IL‐17A mRNA transcription through direct interaction with RORγt. J Biol Chem 2008; 283:17003–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Zhang F, Meng G, Strober W. Interactions among the transcription factors Runx1, RORγt and Foxp3 regulate the differentiation of interleukin 17‐producing T cells. Nat Immunol 2008; 9:1297–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Ciofani M, Madar A, Galan C, Sellars M, Mace K, Pauli F et al A validated regulatory network for Th17 cell specification. Cell 2012; 151:289–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Huh JR, Leung MW, Huang P, Ryan DA, Krout MR, Malapaka RR et al Digoxin and its derivatives suppress TH17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORγt activity. Nature 2011; 472:486–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Xiao S, Yosef N, Yang J, Wang Y, Zhou L, Zhu C et al Small‐molecule RORγt antagonists inhibit T helper 17 cell transcriptional network by divergent mechanisms. Immunity 2014; 40:477–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Rutz S, Kayagaki N, Phung QT, Eidenschenk C, Noubade R, Wang X et al Deubiquitinase DUBA is a post‐translational brake on interleukin‐17 production in T cells. Nature 2015; 518:417–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Mathur AN, Chang HC, Zisoulis DG, Stritesky GL, Yu Q, O'Malley JT et al Stat3 and Stat4 direct development of IL‐17‐secreting Th cells. J Immunol 2007; 178:4901–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Yang XO, Panopoulos AD, Nurieva R, Chang SH, Wang D, Watowich SS et al STAT3 regulates cytokine‐mediated generation of inflammatory helper T cells. J Biol Chem 2007; 282:9358–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Harris TJ, Grosso JF, Yen HR, Xin H, Kortylewski M, Albesiano E et al Cutting edge: an in vivo requirement for STAT3 signaling in TH17 development and TH17‐dependent autoimmunity. J Immunol 2007; 179:4313–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Li P, Spolski R, Liao W, Wang L, Murphy TL, Murphy KM et al BATF‐JUN is critical for IRF4‐mediated transcription in T cells. Nature 2012; 490:543–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Brustle A, Heink S, Huber M, Rosenplanter C, Stadelmann C, Yu P et al The development of inflammatory TH‐17 cells requires interferon‐regulatory factor 4. Nat Immunol 2007; 8:958–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Huber M, Brustle A, Reinhard K, Guralnik A, Walter G, Mahiny A et al IRF4 is essential for IL‐21‐mediated induction, amplification, and stabilization of the Th17 phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105:20846–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Schraml BU, Hildner K, Ise W, Lee WL, Smith WA, Solomon B et al The AP‐1 transcription factor Batf controls TH17 differentiation. Nature 2009; 460:405–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Massague J. TGFβ signalling in context. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012; 13:616–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Zhang YE. Non‐Smad pathways in TGF‐β signaling. Cell Res 2009; 19:128–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Gu AD, Wang Y, Lin L, Zhang SS, Wan YY. Requirements of transcription factor Smad‐dependent and ‐independent TGF‐β signaling to control discrete T‐cell functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109:905–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Martinez GJ, Zhang Z, Reynolds JM, Tanaka S, Chung Y, Liu T et al Smad2 positively regulates the generation of Th17 cells. J Biol Chem 2010; 285:29039–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Martinez GJ, Zhang Z, Chung Y, Reynolds JM, Lin X, Jetten AM et al Smad3 differentially regulates the induction of regulatory and inflammatory T cell differentiation. J Biol Chem 2009; 284:35283–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Lu L, Wang J, Zhang F, Chai Y, Brand D, Wang X et al Role of SMAD and non‐SMAD signals in the development of Th17 and regulatory T cells. J Immunol 2010; 184:4295–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Takimoto T, Wakabayashi Y, Sekiya T, Inoue N, Morita R, Ichiyama K et al Smad2 and Smad3 are redundantly essential for the TGF‐β‐mediated regulation of regulatory T plasticity and Th1 development. J Immunol 2010; 185:842–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Laurence A, Tato CM, Davidson TS, Kanno Y, Chen Z, Yao Z et al Interleukin‐2 signaling via STAT5 constrains T helper 17 cell generation. Immunity 2007; 26:371–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Yoon JH, Sudo K, Kuroda M, Kato M, Lee IK, Han JS et al Phosphorylation status determines the opposing functions of Smad2/Smad3 as STAT3 cofactors in TH17 differentiation. Nat Commun 2015; 6:7600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Frick CL, Yarka C, Nunns H, Goentoro L. Sensing relative signal in the TGF‐β/SMAD pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2017; 114:E2975–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Yang XO, Nurieva R, Martinez GJ, Kang HS, Chung Y, Pappu BP et al Molecular antagonism and plasticity of regulatory and inflammatory T cell programs. Immunity 2008; 29:44–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Hahn JN, Falck VG, Jirik FR. Smad4 deficiency in T cells leads to the Th17‐associated development of premalignant gastroduodenal lesions in mice. J Clin Invest 2011; 121:4030–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Gu AD, Zhang S, Wang Y, Xiong H, Curtis TA, Wan YY. A critical role for transcription factor Smad4 in T cell function that is independent of transforming growth factor β receptor signaling. Immunity 2015; 42:68–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Ong S, Hauri‐Hohl M, Ziegler SF. The role of c‐Ski and TGFβ signaling in autoimmunity. J Immunol 2016; 196:186.7. [Google Scholar]

- 108. Bonnon C, Atanasoski S. c‐Ski in health and disease. Cell Tissue Res 2012; 347:51–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Deheuninck J, Luo K. Ski and SnoN, potent negative regulators of TGF‐β signaling. Cell Res 2009; 19:47–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Baldwin RL, Tran H, Karlan BY. Loss of c‐myc repression coincides with ovarian cancer resistance to transforming growth factor β growth arrest independent of transforming growth factor β/Smad signaling. Cancer Res 2003; 63:1413–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Bright JJ, Sriram S. TGF‐β inhibits IL‐12‐induced activation of Jak‐STAT pathway in T lymphocytes. J Immunol 1998; 161:1772–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Gorelik L, Constant S, Flavell RA. Mechanism of transforming growth factor β‐induced inhibition of T helper type 1 differentiation. J Exp Med 2002; 195:1499–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Wang Y, Su MA, Wan YY. An essential role of the transcription factor GATA‐3 for the function of regulatory T cells. Immunity 2011; 35:337–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Wohlfert EA, Grainger JR, Bouladoux N, Konkel JE, Oldenhove G, Ribeiro CH et al GATA3 controls Foxp3+ regulatory T cell fate during inflammation in mice. J Clin Invest 2011; 121:4503–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Qin H, Wang L, Feng T, Elson CO, Niyongere SA, Lee SJ et al TGF‐β promotes Th17 cell development through inhibition of SOCS3. J Immunol 2009; 183:97–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Biswas PS, Gupta S, Chang E, Song L, Stirzaker RA, Liao JK et al Phosphorylation of IRF4 by ROCK2 regulates IL‐17 and IL‐21 production and the development of autoimmunity in mice. J Clin Invest 2010; 120:3280–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Ichiyama K, Sekiya T, Inoue N, Tamiya T, Kashiwagi I, Kimura A et al Transcription factor Smad‐independent T helper 17 cell induction by transforming‐growth factor‐β is mediated by suppression of eomesodermin. Immunity 2011; 34:741–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Wang Y, Godec J, Ben‐Aissa K, Cui K, Zhao K, Pucsek AB et al The transcription factors T‐bet and Runx are required for the ontogeny of pathogenic interferon‐γ‐producing T helper 17 cells. Immunity 2014; 40:355–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Ivanov II, Frutos Rde L, Manel N, Yoshinaga K, Rifkin DB, Sartor RB et al Specific microbiota direct the differentiation of IL‐17‐producing T‐helper cells in the mucosa of the small intestine. Cell Host Microbe 2008; 4:337–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Burkett PR, Meyer zu Horste G, Kuchroo VK. Pouring fuel on the fire: Th17 cells, the environment, and autoimmunity. J Clin Invest 2015; 125:2211–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Schnupf P, Gaboriau‐Routhiau V, Sansonetti PJ, Cerf‐Bensussan N. Segmented filamentous bacteria, Th17 inducers and helpers in a hostile world. Curr Opin Microbiol 2017; 35:100–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Wu C, Yosef N, Thalhamer T, Zhu C, Xiao S, Kishi Y et al Induction of pathogenic TH17 cells by inducible salt‐sensing kinase SGK1. Nature 2013; 496:513–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Kleinewietfeld M, Manzel A, Titze J, Kvakan H, Yosef N, Linker RA et al Sodium chloride drives autoimmune disease by the induction of pathogenic TH17 cells. Nature 2013; 496:518–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Croxford AL, Waisman A, Becher B. Does dietary salt induce autoimmunity? Cell Res 2013; 23:872–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Wilck N, Matus MG, Kearney SM, Olesen SW, Forslund K, Bartolomaeus H et al Salt‐responsive gut commensal modulates TH17 axis and disease. Nature 2017; 551:585–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Faraco G, Brea D, Garcia‐Bonilla L, Wang G, Racchumi G, Chang H et al Dietary salt promotes neurovascular and cognitive dysfunction through a gut‐initiated TH17 response. Nat Neurosci 2018; 21:240–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Zhou L, Chong MM, Littman DR. Plasticity of CD4+ T cell lineage differentiation. Immunity 2009; 30:646–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Mucida D, Park Y, Kim G, Turovskaya O, Scott I, Kronenberg M et al Reciprocal TH17 and regulatory T cell differentiation mediated by retinoic acid. Science 2007; 317:256–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Knochelmann HM, Dwyer CJ, Bailey SR, Amaya SM, Elston DM, Mazza‐McCrann JM et al When worlds collide: Th17 and Treg cells in cancer and autoimmunity. Cell Mol Immunol 2018; doi: 10.1038/s41423-018-0004-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Chen Y, Haines CJ, Gutcher I, Hochweller K, Blumenschein WM, McClanahan T et al Foxp3+ regulatory T cells promote T helper 17 cell development in vivo through regulation of interleukin‐2. Immunity 2011; 34:409–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Pandiyan P, Conti HR, Zheng L, Peterson AC, Mathern DR, Hernandez‐Santos N et al CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells promote Th17 cells in vitro and enhance host resistance in mouse Candida albicans Th17 cell infection model. Immunity 2011; 34:422–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Cejas PJ, Walsh MC, Pearce EL, Han D, Harms GM, Artis D et al TRAF6 inhibits Th17 differentiation and TGF‐β‐mediated suppression of IL‐2. Blood 2010; 115:4750–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Geng J, Yu S, Zhao H, Sun X, Li X, Wang P et al The transcriptional coactivator TAZ regulates reciprocal differentiation of TH17 cells and Treg cells. Nat Immunol 2017; 18:800–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Dang EV, Barbi J, Yang HY, Jinasena D, Yu H, Zheng Y et al Control of TH17/Treg balance by hypoxia‐inducible factor 1. Cell 2011; 146:772–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Chou TF, Chuang YT, Hsieh WC, Chang PY, Liu HY, Mo ST et al Tumour suppressor death‐associated protein kinase targets cytoplasmic HIF‐1α for Th17 suppression. Nat Commun 2016; 7:11904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Konkel JE, Zhang D, Zanvit P, Chia C, Zangarle‐Murray T, Jin W et al Transforming growth factor‐β signaling in regulatory T cells controls T helper‐17 cells and tissue‐specific immune responses. Immunity 2017; 46:660–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Gagliani N, Amezcua Vesely MC, Iseppon A, Brockmann L, Xu H, Palm NW et al Th17 cells transdifferentiate into regulatory T cells during resolution of inflammation. Nature 2015; 523:221–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Littman DR, Rudensky AY. Th17 and regulatory T cells in mediating and restraining inflammation. Cell 2010; 140:845–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Liu HP, Cao AT, Feng T, Li Q, Zhang W, Yao S et al TGF‐β converts Th1 cells into Th17 cells through stimulation of Runx1 expression. Eur J Immunol 2015; 45:1010–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Lazarevic V, Chen X, Shim JH, Hwang ES, Jang E, Bolm AN et al T‐bet represses TH17 differentiation by preventing Runx1‐mediated activation of the gene encoding RORγt. Nat Immunol 2011; 12:96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Beriou G, Bradshaw EM, Lozano E, Costantino CM, Hastings WD, Orban T et al TGF‐β induces IL‐9 production from human Th17 cells. J Immunol 2010; 185:46–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Hirota K, Turner JE, Villa M, Duarte JH, Demengeot J, Steinmetz OM et al Plasticity of Th17 cells in Peyer's patches is responsible for the induction of T cell‐dependent IgA responses. Nat Immunol 2013; 14:372–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Schmitt N, Liu Y, Bentebibel SE, Munagala I, Bourdery L, Venuprasad K et al The cytokine TGF‐β co‐opts signaling via STAT3‐STAT4 to promote the differentiation of human TFH cells. Nat Immunol 2014; 15:856–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Barbi J, Pardoll D, Pan F. Metabolic control of the Treg/Th17 axis. Immunol Rev 2013; 252:52–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Wang C, Yosef N, Gaublomme J, Wu C, Lee Y, Clish CB et al CD5L/AIM regulates lipid biosynthesis and restrains Th17 cell pathogenicity. Cell 2015; 163:1413–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Bantug GR, Hess C. The burgeoning world of immunometabolites: Th17 cells take center stage. Cell Metab 2017; 26:588–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Kidani Y, Bensinger SJ. Reviewing the impact of lipid synthetic flux on Th17 function. Curr Opin Immunol 2017; 46:121–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Saxton RA, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell 2017; 168:960–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Delgoffe GM, Pollizzi KN, Waickman AT, Heikamp E, Meyers DJ, Horton MR et al The kinase mTOR regulates the differentiation of helper T cells through the selective activation of signaling by mTORC1 and mTORC2. Nat Immunol 2011; 12:295–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Kurebayashi Y, Nagai S, Ikejiri A, Ohtani M, Ichiyama K, Baba Y et al PI3K‐Akt‐mTORC1‐S6K1/2 axis controls Th17 differentiation by regulating Gfi1 expression and nuclear translocation of RORγ . Cell Rep 2012; 1:360–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Yu JS, Ramasamy TS, Murphy N, Holt MK, Czapiewski R, Wei SK et al PI3K/mTORC2 regulates TGF‐β/Activin signalling by modulating Smad2/3 activity via linker phosphorylation. Nat Commun 2015; 6:7212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Shi LZ, Wang R, Huang G, Vogel P, Neale G, Green DR et al HIF1α‐dependent glycolytic pathway orchestrates a metabolic checkpoint for the differentiation of TH17 and Treg cells. J Exp Med 2011; 208:1367–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. McMahon S, Charbonneau M, Grandmont S, Richard DE, Dubois CM. Transforming growth factor β1 induces hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1 stabilization through selective inhibition of PHD2 expression. J Biol Chem 2006; 281:24171–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Wang R, Dillon CP, Shi LZ, Milasta S, Carter R, Finkelstein D et al The transcription factor Myc controls metabolic reprogramming upon T lymphocyte activation. Immunity 2011; 35:871–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Seoane J, Pouponnot C, Staller P, Schader M, Eilers M, Massague J. TGFβ influences Myc, Miz‐1 and Smad to control the CDK inhibitor p15INK4b. Nat Cell Biol 2001; 3:400–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Staller P, Peukert K, Kiermaier A, Seoane J, Lukas J, Karsunky H et al Repression of p15INK4b expression by Myc through association with Miz‐1. Nat Cell Biol 2001; 3:392–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Frederick JP, Liberati NT, Waddell DS, Shi Y, Wang XF. Transforming growth factor β‐mediated transcriptional repression of c‐myc is dependent on direct binding of Smad3 to a novel repressive Smad binding element. Mol Cell Biol 2004; 24:2546–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. Quintana FJ, Basso AS, Iglesias AH, Korn T, Farez MF, Bettelli E et al Control of Treg and TH17 cell differentiation by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature 2008; 453:65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159. Veldhoen M, Hirota K, Westendorf AM, Buer J, Dumoutier L, Renauld JC et al The aryl hydrocarbon receptor links TH17‐cell‐mediated autoimmunity to environmental toxins. Nature 2008; 453:106–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160. Apetoh L, Quintana FJ, Pot C, Joller N, Xiao S, Kumar D et al The aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacts with c‐Maf to promote the differentiation of type 1 regulatory T cells induced by IL‐27. Nat Immunol 2010; 11:854–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161. Rutz S, Noubade R, Eidenschenk C, Ota N, Zeng W, Zheng Y et al Transcription factor c‐Maf mediates the TGF‐β‐dependent suppression of IL‐22 production in TH17 cells. Nat Immunol 2011; 12:1238–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162. Wolff S, Harper PA, Wong JM, Mostert V, Wang Y, Abel J. Cell‐specific regulation of human aryl hydrocarbon receptor expression by transforming growth factor‐β 1 . Mol Pharmacol 2001; 59:716–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163. Harper PA, Riddick DS, Okey AB. Regulating the regulator: factors that control levels and activity of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Biochem Pharmacol 2006; 72:267–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164. Bussmann UA, Baranao JL. Interaction between the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and transforming growth factor‐β signaling pathways: evidence of an asymmetrical relationship in rat granulosa cells. Biochem Pharmacol 2008; 76:1165–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165. Berod L, Friedrich C, Nandan A, Freitag J, Hagemann S, Harmrolfs K et al De novo fatty acid synthesis controls the fate between regulatory T and T helper 17 cells. Nat Med 2014; 20:1327–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166. Blagih J, Coulombe F, Vincent EE, Dupuy F, Galicia‐Vazquez G, Yurchenko E et al The energy sensor AMPK regulates T cell metabolic adaptation and effector responses in vivo . Immunity 2015; 42:41–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]