Abstract

Dehydroalanine (Dha) and dehydrobutyrine (Dhb) are remarkably versatile non‐canonical amino acids often found in antimicrobial peptides. This work presents the selective modification of Dha and Dhb in antimicrobial peptides through photocatalytic activation of organoborates under the influence of visible light. Ir(dF(CF3)ppy)2(dtbbpy)PF6 was used as a photoredox catalyst in aqueous solutions for the modification of thiostrepton and nisin. The mild conditions and high selectivity for the dehydrated residues show that photoredox catalysis is a promising tool for the modification of peptide‐derived natural products.

Keywords: bio-orthogonal catalysis, dehydroalanine, nisin, photoredox catalysis, thiostrepton

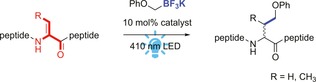

Site‐selective modification of peptide‐derived natural products is a promising strategy to obtain new therapeutics. However, potentially interesting targets are often products of sophisticated biological post‐translational machineries, and therefore difficult to modify by means of common bio‐orthogonal chemistry1 or bio‐engineering approaches.2 Many of these structures contain unique non‐canonical amino acids, which are attractive targets for late‐stage chemical modification. Particularly interesting residues are dehydroalanine (Dha) and dehydrobutyrine (Dhb). These are commonly found in ribosomally synthesized and post‐translationally modified peptides (RiPPs), such as the lanthi‐ and thiopeptides, which are of interest due to their antimicrobial activity.3 The unique orthogonal reactivity of the double bond in these dehydrated amino acids is used by nature to introduce, for example, lanthionine rings and piperidine moieties. It has been shown that residual dehydrated residues can undergo a variety of chemical modifications;4 however, catalytic strategies are scarce. Catalytic activation of an unreactive precursor could provide new strategies for modification of the complex peptides under mild conditions. Here, we present the selective late‐stage modification of Dha and Dhb in antimicrobial peptides by photocatalysis, using trifluoroborate salts as radical precursors.

In recent years, photoredox catalysis has emerged as a mild method for visible‐light‐induced activation of small molecules.5 Furthermore, photocatalysis is compatible with peptides and proteins, as was shown in the photocatalytic induced formation of peptide macrocycles,6 site‐selective modification of cysteine in peptides,7 trifluoromethylation of peptides,8 and decarboxylative alkylation of proteins.9 Typically, cyclometalated polypyridyl iridium complexes or bipyridyl ruthenium complexes generate organic radicals by oxidative or reductive quenching of their excited states. Precursors like organoborates, which are harmless and air‐ and moisture‐stable compounds, are known to generate carbon‐centered radicals upon oxidation by an excited photocatalyst. These radicals react readily with electron‐deficient alkenes.10 Considering the electron‐deficient character of Dha, together with the orthogonal reactivity of organoborates, and the mild conditions of visible‐light irradiation, we envisioned this method could be employed for photocatalytic modification of Dha and Dhb in natural antimicrobial peptides (see Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Chemical modification of Dha and Dhb in peptides by photoredox catalysis.

Initial studies focused on the photocatalytic modification of the Dha monomer (1 a) with potassium (p‐methoxyphenoxy)methyl‐trifluoroborate (2 a) (see Table 1). Different commonly used photocatalysts like Ir(ppy)2(dtbbpy)PF6 (5), Ir(dF(CF3)ppy)2(dtbbpy)PF6 (6), and Ru(bpy)3Cl2 (7) were evaluated for this reaction in aqueous solution mixed with various amounts of organic co‐solvent under the influence of blue light (LED 410 nm) for 16 h at room temperature. Catalysts 5 and 6 were found to be insoluble in most of the aqueous mixtures (Table S1, Supporting Information), resulting in precipitation of the catalyst and therewith no formation of product 3 a was obtained (Table 1, entries 1 and 2). Photocatalyst 7 is water soluble, but no product formation was observed either (entry 3). Only in the case of 50 % acetone (aq), 50 % 1,4‐dioxane (aq) and 100 % DMF with catalyst 6 conversion to 3 a was obtained (entries 4–6). In the case of the Dhb monomer (1 b), the corresponding product 4 a was obtained (entry 6). Control reactions in which the reaction was performed in the dark, without catalyst, or with addition of radical scavenger TEMPO, resulted in no conversion, indicating the organoborate is indeed converted into a radical species by means of photoredox catalysis (entries 8–10).

Table 1.

Results of photocatalytic reaction of Dha monomer with 2 a.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Substrate | Co‐solvent | % H2O | Catalyst[c] | Yield[a] |

| 1 | 1 a | – | 100 | 5 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 a | – | 100 | 6 | 0 |

| 3 | 1 a | – | 100 | 7 | 0 |

| 4 | 1 a | Acetone | 50 | 6 | 57 % (41 %) |

| 5 | 1 a | 1,4‐Dioxane | 50 | 6 | full (64 %) |

| 6 | 1 a | DMF | 0 | 6 | 56 % (40 %) |

| 7 | 1 b | Acetone | 50 | 6 | full (82 %) |

| 8 | 1 a | Methanol | 50 | 6 | 0 |

| 9[b] | 1 a | Acetone | 50 | 6 | 0 |

| 10[c] | 1 a | Acetone | 50 | 6 | 0 |

Reaction conditions: a mixture of 1 (10 mm), 2 a (20 mm), and photocatalyst (2 mol %) dissolved or suspended in the degassed solvent mixture, and irradiated with blue LEDs for 16 h at room temperature. [a] Conversion and yield determined by 1H‐NMR with 20 mm internal standard 1,3,5‐trimethoxybenzene. yield in parentheses; [b] reaction performed in the dark; [c] reaction performed in the presence of TEMPO (10 mm).

The photocatalytic reaction was then tested on Dha and Dhb in a peptide. The antimicrobial peptide thiostrepton is a hydrophobic thiopeptide, soluble in apolar solvents like chloroform, 1,4‐dioxane, and DMF, which is comparable with the conditions found in the screening. Thiostrepton was therefore mixed with 2 a (6 equiv, 1.5 equiv per dehydrated amino acid), and 10 mol % 6 in aqueous 1,4‐dioxane (9:1 (v/v)). The presence of water was required to fully dissolve the trifluoroborate salt. The reaction mixture was irradiated with blue LEDs for one hour, after which an aliquot of the reaction was analyzed by LC/MS. Single‐ and double‐modified thiostrepton were observed as main products. Extension of the irradiation time by another two hours gave rise to triple‐ and quadruple modification of the peptide, which corresponds to the total number of dehydrated amino acids present.

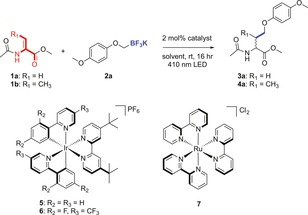

The scope of the reaction was investigated by varying the trifluoroborate salts. It was found that the reaction is significantly affected by the substituents present on the aryl ring of the substrate (see Figure 1). Electron‐donating groups result in (almost) full conversion of the starting material (8 a–c), whereas fewer electron‐donating groups on the aryl ring slows down the reaction, resulting in mostly single modification and remaining starting material (8 d–f). This might be due to the nucleophilicity of the generated radicals, or the difference in electrochemical potential to generate radicals from the trifluoroborate salts. Moreover, the oxygen next to the carbon‐centered radical turned out to have a beneficial effect on the reaction. By using substrates that lack the heteroatom, the reaction was much slower (8 g), resulting in no conversion (8 h) or in degradation of the peptide. In the absence of the aryl moiety, only degradation products were obtained (Table S2, Supporting Information).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the photocatalytic reaction on thiostrepton. Dha residues are depicted in red and Dhb residue in orange. Scope of trifluoroborate salts for photocatalytic modification of thiostrepton, optimized conditions: thiostrepton (500 μm), trifluoroborate salt (3 mm), and 6 (50 μm) in 400 μL 1,4‐dioxane/ water (9:1) irradiated with blue LED (410 nm) at room temperature for 3 h. Single modification (*), double modification (**), and triple modification (***) is observed. Conversion (in parentheses) is calculated based on integration of the EIC of the corresponding product divided by the sum of the areas of all compounds, assuming that ionization is similar for all products, which are structurally very similar.11

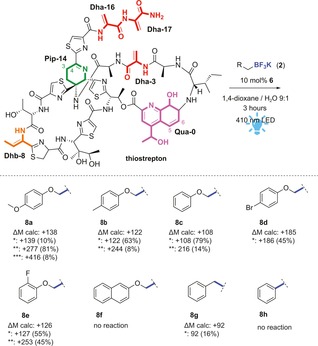

To determine the site of modification, single‐modified thiostrepton product 8 c was purified by rp‐HPLC, and studied by 1H‐NMR. The two peaks indicated with the blue star in the LC chromatogram (Figure 2 a) were established to be two diasteriomers of modification at the same position of the peptide, which could be separated by rp‐HPLC (Figure 2 b). Comparison of the 1H‐NMR spectrum of purified 8 c with the 1H‐NMR spectrum of unmodified thiostrepton shows the disappearance of two singlets at 6.73 and 5.50 ppm and a shift of the singlets at 6.63 and 5.38 ppm (Figure 2 c). These four signals correspond to the four β‐protons of Dha‐16 and Dha‐17, the dehydrated residues in the tail of the peptide. The signals of the other double bonds in the peptide (i.e., Dha‐3, Dhb‐8, piperidine‐14, and quinaldic acid‐0) remained unchanged, which indicates that the peptide is modified at a Dha in the tail. 2D NMR TOCSY measurements confirmed the modification to be at Dha‐16 (Figure S1 c, Supporting Information). These results show the photocatalytic modification to be selective for the dehydrated amino acids. Moreover, the reaction is chemoselective for Dha‐16, which is known to be the most electron deficient dehydrated residue due to it being situated next to a thiazole ring. Single modification at other positions is observed in the UPLC chromatogram of the crude reaction mixture (Figure 2 a), but these products are formed only in low yields, as can be calculated from the low intensity of the peaks of these products.

Figure 2.

Determination of modification site in thiostrepton; a) UPLC chromatogram (280 nm) of crude reaction mixture 8 c: degr.=degraded thiostrepton due to base‐mediated tail cleavage,12 s.m.=starting material, *=single‐modified thiostrepton, mixture of two diastereomers, **=double modified thiostrepton; b) UPLC chromatogram (280 nm) of purified 8 c; c) NMR studies on photocatalytically modified thiostrepton (8 c, orange) compared with unmodified thiostrepton (blue). Zoom in of 5–7 ppm to show signal shifts of Dha‐17 and signal disappearance of Dha‐16.

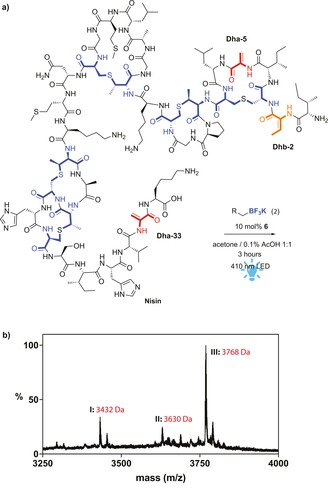

To show the versatility of our approach, the lantipeptide nisin was subjected to the photoredox catalysis. Nisin is less hydrophobic than thiostrepton. Hence, the photocatalytic reaction on nisin was performed in 1,4‐dioxane or acetone with 50 % water containing 0.1 % AcOH (aq). Nisin was reacted with 2 a (4.5 equiv, 1.5 equiv per dehydrated residue), catalyzed by 10 mol % 6. After irradiation with blue LEDs for 1 h almost full conversion to triple‐modified nisin was obtained, as can be seen from the MALDI‐TOF spectrum (Figure 3 b). Exploration of the scope of the reaction on nisin showed a similar trend as in the case of thiostrepton (see Table S3). The best results were obtained when both the aryl ring as well as the heteroatom adjacent to the carbon‐centered radical are present (9 a–c). Less donating substituents on the phenyl ring result in lower conversion and mainly single‐modified product (9 b,c). Organoborates with less electron‐donating substituents like halogens resulted in no conversion at all (9 d,e). Addition of TEMPO as radical scavenger gave unmodified starting material, confirming the involvement of radical species and showing that the peptide is stable under the conditions of the photocatalytic reaction.11c

Figure 3.

a) Schematic representation of the photocatalytic modification of nisin; b) MALDI‐TOF measurement of the crude product of the photocatalytic modification of nisin with 2 a I) degraded Nisin(CH2OPhOMe)2 due to water addition followed by hydrolytic cleavage of the C‐terminal region,13 II) Nisin(CH2OPhOMe)2, III) Nisin(CH2OPhOMe)3.

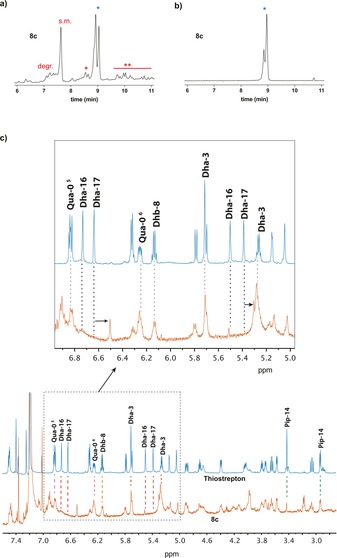

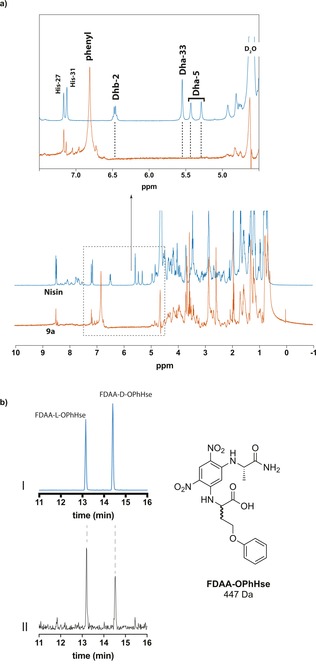

To determine the selectivity of the photocatalytic modification of nisin, triple‐modified product 9 a was studied by NMR spectroscopy. The 1H‐NMR spectrum of this product revealed that the peaks of Dha‐5 (5.35 and 5.48 ppm), Dha‐33 (5.60 ppm), and Dhb‐2 (6.51 ppm) had disappeared (see Figure 4 a). Hence, the photocatalytically generated radicals react selectively with the dehydrated amino acids in the peptide, yielding an O‐phenylhomoserine (OPhHse) residue. To confirm the presence of this newly formed residue, modified nisin (9 c) was hydrolyzed in a microwave oven in 6 m HCl (aq) to study the amino acids present. The hydrolysate was reacted with Marfey's reagent (1‐fluoro‐2,4‐dinitrophenyl‐5‐l‐alanine amide (FDAA)).14 Analysis with LC/MS and comparison with FDAA‐derivatized OPhHse confirmed the presence of OPhHse in 9 c. (see Figure 4 b).

Figure 4.

Analysis of the site selectivity of photocatalytic modified nisin. a) NMR studies on photocatalytically modified nisin (9 a, orange) compared with unmodified nisin (blue). Inset: Zoomed in view of 4.5–7.5 ppm to show signal disappearance of Dhb‐2, Dha‐5, and Dha‐33; b) Analysis of introduced O‐phenylhomoserine using Marfey's method: (I) Extracted ion chromatogram (EIC) of [M+H]=448 Da corresponding to d/l‐OPhHse derivatized with FDAA; (II) EIC of the hydrolysate of 9 c derivatized with FDAA.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that visible‐light‐driven photoredox catalysis is an efficient and mild catalytic method for the selective late‐stage modification of dehydrated amino acids in antimicrobial peptides. Dha and Dhb react selectively with the carbon‐centered radicals generated from organoborates with only 10 mol % catalyst loading in aqueous conditions. This study illustrates the potential of photoredox catalysis for the late‐stage modification of complex active natural products and is therefore a promising tool in the quest for new antibiotics.

Experimental Section

General procedure of photocatalytic modification of thiostrepton

Catalysis was performed in dioxane/H2O (9:1) with a final concentration of 500 μm peptide, 2 mm organoborate, and 50 μm catalyst. A typical catalysis reaction was set up as follows: Thiostrepton (0.2 mmol in 316 μL dioxane) and 80 μL of a 10 mm organoborate stock solution (dioxane/H2O 1:1) were combined. 4 μL of 5 mm catalyst stock solution in DMF was added in a Schlenk vial. The mixture was degassed by three repeated freeze–pump–thaw cycles. The Schlenk was placed under nitrogen atmosphere and exposed to blue LEDs for 3 h at room temperature. The reaction mixture was analyzed by UPLC/MS TQD directly.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Reinder de Vries for useful discussion on the NMR analysis, Prof. Dr. Wesley Browne for advice and initial photocatalysis set‐ups, and Ing. Pieter van der Meulen for design and manufacturing of a permanent photocatalysis set‐up. Financial support from the Netherlands Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (Gravitation program no. 024.001.035) and the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO, vici grant 724.013.003) is gratefully acknowledged.

A. D. de Bruijn, G. Roelfes, Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 11314.

References

- 1.

- 1a. Prescher J. A., Bertozzi C. R., Nat. Chem. Biol. 2005, 1, 13; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Ramil C. P., Lin Q., Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 11007–11022; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1c. Koopmans T., Wood T. M., ′t Hart P., Kleijn L. H., Hendrickx A. P., Willems R. J., Breukink E., Martin N. I., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 9382–9389; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1d. Slootweg J. C., van der Wal S., van Ufford H. C. Q., Breukink E., Liskamp R. M., Rijkers D. T., Bioconjugate Chem. 2013, 24, 2058–2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. Shi Y., Yang X., Garg N., van der Donk W. A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 2338–2341; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Zhou L., Shao J., Li Q., van Heel A. J., de Vries M. P., Broos J., Kuipers O. P., Amino Acids 2016, 48, 1309–1318; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2c. Just-Baringo X., Albericio F., Alvarez M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 6602; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 6720; [Google Scholar]

- 2d. Repka L. M., Chekan J. R., Nair S. K., van der Donk W. A., Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 5457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.

- 3a. Palmer D. E., Pattaroni C., Nuami K., Chadba R. K., Goodman M., Wakamiya T., Fukase K., Horimot S., Kitazawa M., Fujita H., Kubo A., Shiba T., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 5634; [Google Scholar]

- 3b. Knerr P. J., van der Donk W. A., Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2012, 81, 479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.

- 4a. Chalker J. M., Gunnoo S. B., Boutureira O., Gerstberger S. C., Fernández-González M., Bernardes G. J. L., Griffin L., Hailu H., Schofield C. J., Davis B. G., Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 1666; [Google Scholar]

- 4b. Freedy A. M., Matos M. J., Boutureira O., Corzana F., Guerreiro A., Akkapeddi P., Somovilla V. J., Rodrigues T., Nicholls K., Xie B., Jimenez-Oses G., Brindle K. M., Neves A. A., Bernardes G. J. L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 18365; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4c. Aronoff M. R., Gold B., Raines R. T., Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 1538; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4d. Wright T. H., Bower B. J., Chalker J. M., Bernardes G. J. L., Wiewiora R., Ng W.-L., Raj R., Faulkner S., Vallee M. R. J., Phanumartwiwath A., Coleman O. D., Thezenas M.-L., Khan M., Galan S. R. G., Lercher L., Schombs M. W., Gerstberger S., Palm-Espling M. E., Baldwin A. J., Kessler B. M., Claridge T. D. W., Mohammed S., Davis B. G., Science 2016, 354, aag1465; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4e. Yang A., Ha S., Ahn J., Kim R., Kim S., Lee Y., Kim J., Söll D., Lee H. Y., Park H. S., Science 2016, 354, 623; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4f. Gober J. G., Ghodge S. V., Bogart J. W., Wever W. J., Watkins R. R., Brustad E. M., Bowers A. A., ACS Chem. Biol. 2017, 12, 1726; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4g. Key H. M., Miller S. J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 15460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shaw M. H., Twilton J., MacMillan D. W., J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 6898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McCarver S. J., Qiao J. X., Carpenter J., Borzilleri R. M., Poss M. A., Eastgate M. D., Miller M. M., MacMillan D. W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 728; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 746. [Google Scholar]

- 7.

- 7a. Bottecchia C., Rubens M., Gunnoo S. B., Hessel V., Madder A., Noël T., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 12702; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 12876; [Google Scholar]

- 7b. Vara B. A., Li X., Berritt S., Walters C. R., Petersson E. J., Molander G. A., Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 336–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ichiishi N., Caldwell J. P., Lin M., Zhong W., Zhu X., Streckfuss E., Kim H. Y., Parish C. A., Krska S. W., Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 4168–4175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bloom S., Liu C., Kolmel D. K., Qiao J. X., Zhang Y., Poss M. A., Ewing W. R., MacMillan D. W. C., Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.

- 10a. Molander G. A., Sandrock D. L., Curr. Opin. Drug Discovery Devel. 2009, 12, 811; [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10b. Yasu Y., Koike T., Akita M., Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012, 354, 3414; [Google Scholar]

- 10c. Miyazawa K., Yasu Y., Koike T., Akita M., Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 7249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.

- 11a. Hicks L. M., O'Connor S. E., Mazur M. T., Walsh C. T., Kelleher N. L., Chem. Biol. 2004, 11, 327–335; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11b. Wang H. Z. W., Lin H., Roy S., Shaler T. A., Hill L. R., Norton S., Kumar p., Anderle M., Becker C. H., Anal. Chem. 2003, 75, 4818; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11c. Thibodeaux C. J., Ha T., van der Donk W. A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 17513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jonker H. R., Baumann S., Wolf A., Schoof S., Hiller F., Schulte K. W., Kirschner K. N., Schwalbe H., Arndt H. D., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 3308–3312; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2011, 123, 3366–3370. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rollema J. W. M. H. S., Both P., Kuipers O. P., Siezen R. J., Eur. J. Biochem. 1996, 241, 716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Marfey P., Carlsberg Res. Commun. 1984, 49, 591. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary