Abstract

Aims

To assess the effect of baseline body mass index (BMI) and the occurrence of nausea and/or vomiting on weight loss induced by semalgutide, a once‐weekly glucagon‐like peptide 1 analogue for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Semaglutide demonstrated superior reductions in HbA1c and superior weight loss (by 2.3‐6.3 kg) versus different comparators across the SUSTAIN 1 to 5 trials; the contributing factors to weight loss are not established.

Materials and Methods

Subjects with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes (drug‐naïve or on background treatment) were randomized to subcutaneous semaglutide 0.5 mg (excluding SUSTAIN 3), 1.0 mg (all trials), or comparator (placebo, sitagliptin, exenatide extended release or insulin glargine). Subjects were subdivided by baseline BMI and reporting (yes/no) of any nausea and/or vomiting. Change from baseline in body weight was assessed within each trial and subgroup. A mediation analysis separated weight loss into direct or indirect (mediated by nausea or vomiting) effects.

Results

Clinically relevant weight‐loss differences were observed across all BMI subgroups, with a trend towards higher absolute weight loss with higher baseline BMI. Overall, 15.2% to 24.0% and 21.5% to 27.2% of subjects experienced nausea or vomiting with semaglutide 0.5 and 1.0 mg, respectively, versus 6.0% to 14.1% with comparators. Only 0.07 to 0.5 kg of the treatment difference between semaglutide and comparators was mediated by nausea or vomiting (indirect effects).

Conclusions

In SUSTAIN 1 to 5, semaglutide‐induced weight loss was consistently greater versus comparators, regardless of baseline BMI. The contribution of nausea or vomiting to this weight loss was minor.

Keywords: BMI, gastrointestinal adverse events, GLP‐1 analogue, GLP‐1 based therapy, nausea, type 2, vomiting, weight control, weight loss

1. INTRODUCTION

Overweight and obesity in patients with type 2 diabetes is associated with increased cardiovascular (CV) morbidity, including heart failure, stroke and hypertension,1, 2 as well as other complications, including some types of cancer3 and a reduced quality of life.4

Reducing body weight mitigates both diabetes‐ and CV‐related risks; a weight loss of at least 5% improves glucose, lipid and blood pressure control in overweight or obese patients with type 2 diabetes.5

The Look AHEAD study of behavioural interventions to promote weight loss in type 2 diabetes also showed that a greater magnitude of weight loss is associated with improved long‐term (>4 years) glycaemic control,6 although no significant effect on CV outcomes was observed after a median follow‐up of 10 years.7

Body weight control is, therefore, an important component of an individualized, multifactorial approach to diabetes management, and this is highlighted in recent treatment guidelines.8, 9, 10

Weight loss is a recognized outcome of glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonist (GLP‐1RA) therapy and all currently available GLP‐1RAs (albiglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide, liraglutide and lixisenatide) promote weight loss in subjects with type 2 diabetes to varying extents.11, 12

Semaglutide (Novo Nordisk, Denmark) is a new glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) analogue for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, with 94% amino acid sequence homology to native GLP‐1 and with a half‐life of approximately 1 week.13, 14 In the SUSTAIN clinical trial programme, consisting of seven global clinical trials including more than 8000 adults with type 2 diabetes, semaglutide demonstrated superior reductions from baseline in both HbA1c and body weight versus placebo and active comparators (sitagliptin, exenatide extended release [ER], insulin glargine and dulaglutide).15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 The SUSTAIN 6 trial also demonstrated a reduction in the risk of CV outcomes with semaglutide versus placebo over 2 years in subjects at high risk for CV events.20

Factors associated with semaglutide‐induced weight loss are not fully known. Since the most common adverse events (AEs) reported in the studies with semaglutide were gastrointestinal (GI), these AEs may have contributed to the weight loss. Furthermore, it is not known whether baseline body mass index (BMI) affects the degree of semaglutide‐induced weight loss.

This post hoc analysis of the SUSTAIN 1 to 5 trials aims to evaluate the consistency of semaglutide‐induced weight loss across baseline BMI (kg/m2) subgroups, and to further elucidate the relationship between nausea/vomiting AEs and weight loss. The data for SUSTAIN 7 were not available at the time of this analysis, and have therefore not been included.21

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design

We conducted a post hoc efficacy analysis by trial using all subjects in the global phase 3a SUSTAIN 1 to 5 randomized clinical trial programme. The study designs of these trials are summarized in Table S1 (see the Supporting Information for this article) and have been reported previously.15, 16, 17, 18, 19 The programme included subjects spanning the diabetes continuum of care: drug‐naïve (SUSTAIN 1); on metformin and/or thiazolidinediones (SUSTAIN 2); on 1 to 2 therapies comprising metformin, thiazolidinediones or sulfonylureas (SUSTAIN 3); on metformin ± sulfonylureas (SUSTAIN 4); or on basal insulin ± metformin (SUSTAIN 5).

In these 5 trials across a total of 33 countries, 3918 adult subjects with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes (HbA1c 7.0% to 10.0% [53 to 86 mmol/mol] for SUSTAIN 1, 4 and 5; 7.0% to 10.5% [53 to 91 mmol/mol] for SUSTAIN 2 and 3) were randomized to semaglutide 0.5 mg, semaglutide 1.0 mg or a comparator: placebo (SUSTAIN 1, 5), sitagliptin 100 mg (SUSTAIN 2), exenatide ER (SUSTAIN 3), and titrated insulin glargine (SUSTAIN 4) for 30 or 56 weeks.15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Subjects were followed throughout the planned trial period.

Two semaglutide maintenance dose levels (0.5 and 1.0 mg once‐weekly) were used in each trial except for SUSTAIN 3, in which only the 1.0 mg dose was used. Semaglutide was administered using a pre‐filled pen injection device. Semaglutide‐treated subjects followed a fixed‐dose escalation regimen to improve GI tolerability. The semaglutide 0.5 mg maintenance dose was reached after 4 weeks of semaglutide 0.25 mg once‐weekly, and the semaglutide 1.0 mg maintenance dose was reached after 4 weeks of semaglutide 0.25 mg once‐weekly, followed by 4 weeks of semaglutide 0.5 mg once‐weekly.

2.2. Patient population

The key inclusion/exclusion criteria were similar across the SUSTAIN 1 to 5 trials. Subjects were eligible for inclusion if they were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, were ≥18 years of age, had an HbA1c ≥7.0% to 10.0% (53 to 86 mmol/mol [SUSTAIN 1, 4 and 5]) or ≥7.0% to 10.5% (53 to 91 mmol/mol [SUSTAIN 2 and 3]) with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) >30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (SUSTAIN 2 and 3: eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2). Key exclusion criteria were: history of chronic or idiopathic acute pancreatitis; known proliferative retinopathy or maculopathy requiring acute treatment; screening calcitonin value ≥50 ng/L; a personal/family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2; an acute coronary or cerebrovascular event within 90 days before randomization; or heart failure New York Heart Association class IV.15, 16, 17, 18, 19

All trials were conducted in compliance with the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines22 and the Declaration of Helsinki.23 The protocol was approved by local ethics committees and institutional review boards. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before trial commencement.

2.3. Study endpoints and assessments

In the pre‐planned analyses, the key endpoints were similar across all of the SUSTAIN 1 to 5 trials. The primary endpoint was the change in HbA1c from baseline to end of treatment (30 or 56 weeks). The confirmatory secondary endpoint was the change in body weight from baseline to end of treatment (30 or 56 weeks). Other secondary endpoints presented in these analyses were the proportions of subjects achieving ≥5% or ≥10% weight loss, and safety parameters including AEs.15, 16, 17, 18, 19

2.4. Post hoc analyses

Analyses were based on data from subjects while they were on treatment without using rescue medication.

Subjects in the SUSTAIN 1 to 5 trials were subdivided by baseline BMI (<25, 25 to <30, 30 to <35, ≥35 kg/m2), from a baseline BMI range of 16.35 to 72.84 kg/m2. Change from baseline in body weight and the proportions of subjects achieving ≥5% and ≥10% weight loss were assessed versus the corresponding comparator within each trial and subgroup. Change in body weight from baseline was estimated from a mixed model for repeated measurements with treatment and baseline BMI subgroup as fixed factors, interaction between treatment and BMI subgroup at baseline and baseline body weight as covariate, all nested within visit. The proportions of subjects with an imputed value for end‐of‐treatment body weight were 16.4% to 29.4%.

Subjects achieving ≥5% and ≥10% weight loss were analyzed using a logistic regression model with treatment versus subgroup interaction and baseline body weight as covariate with missing data imputed from the corresponding mixed model for repeated measurements for change from baseline.

In a separate analysis, subjects in the SUSTAIN 1 to 5 trials were subdivided according to whether or not they had spontaneously reported any nausea and/or vomiting GI AEs. A mediation analysis was performed to separate the overall effect on weight into direct or indirect (mediated by nausea or vomiting) effects, which were estimated using natural effect models with imputation‐based estimation.24 The natural effect model included the interaction between treatment and any nausea or vomiting together with the baseline variables of body weight, country and stratification factors (for SUSTAIN 4 and 5 only) as main effects, assuming no interaction between natural effects and baseline variables (confidence intervals were percentile bootstrap estimates). For SUSTAIN 4, data were stratified according to oral antidiabetic agent use (metformin versus metformin + sulfonylurea) and, for SUSTAIN 5, stratification factors were baseline HbA1c (>8.0%, ≤8.0%) and metformin use (yes/no). The model used to impute counterfactual values of body weight also included the interaction between treatment and each baseline variable and the interaction between any nausea or vomiting and each baseline variable.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Subject disposition and baseline characteristics

Overall, 3918 subjects with type 2 diabetes who were treatment‐naïve (SUSTAIN 1) or on a background of glucose‐lowering drugs (metformin, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones in SUSTAIN 2 to 4 and basal insulin ± metformin in SUSTAIN 5) were randomized to once‐weekly subcutaneous (s.c.) semaglutide 0.5 or 1.0 mg or comparator treatment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and subject disposition across the SUSTAIN 1 to 5 trials

| SUSTAIN 1: Semaglutide vs. placebo | SUSTAIN 2: Semaglutide vs. sitagliptin 100 mg | SUSTAIN 3: Semaglutide vs. exenatide ER 2.0 mg | SUSTAIN 4: Semaglutide vs. IGlar | SUSTAIN 5: Semaglutide add‐on to insulin vs. placebo | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 wk | 56 wk | 56 wk | 30 wk | 30 wk | |

| Baseline characteristics, mean (SD) a | |||||

| Age (years) | 53.7 (11.3) | 55.1 (10.0) | 56.6 (10.7) | 56.5 (10.4) | 58.8 (10.1) |

| Men (%) | 54.3 | 50.6 | 55.3 | 53.0 | 56.1 |

| Diabetes duration (y) | 4.2 (5.5) | 6.6 (5.1) | 9.2 (6.3) | 8.6 (6.3) | 13.3 (7.8) |

| Body weight (kg) | 91.9 (23.8) | 89.5 (20.3) | 95.8 (21.5) | 93.5 (21.8) | 91.7 (21.0) |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.1 (0.9) | 8.1 (0.9) | 8.3 (1.0) | 8.2 (0.9) | 8.4 (0.8) |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 64.5 (9.3) | 64.8 (10.1) | 67.7 (10.4) | 65.8 (9.7) | 67.9 (9.2) |

| FPG (mg/dL) | 175.7 (48.2) | 169.4 (40.7) | 189.0 (48.7) | 175.3 (51.2) | 155.9 (53.7) |

| BMI (kg/m 2 ) | 32.9 (7.7) | 32.5 (6.2) | 33.8 (6.7) | 33.0 (6.5) | 32.2 (6.2) |

| Subject disposition, N (%) | |||||

| Randomized | 388 | 1231 | 813 | 1089 | 397 |

| Exposed | 387 (99.7) | 1225 (99.5) | 809 (99.5) | 1082 (99.4) | 396 (99.7) |

| Trial completers | 359 (92.5) | 1163 (94.5) | 743 (91.4) | 1020 (93.7) | 380 (95.7) |

| Premature treatment discontinuation | 47 (12.1) | 146 (11.9) | 167 (20.6) | 130 (12.0) | 43 (10.9) |

| Semaglutide 0.5 mg | 17 (13.3) | 53 (13.0) | N/A | 49 (13.5) | 14 (10.6) |

| Semaglutide 1.0 mg | 16 (12.3) | 61 (14.9) | 82 (20.3) | 55 (15.3) | 16 (12.2) |

| Comparator | 14 (10.9) | 32 (7.9) | 85 (21.0) | 26 (7.2) | 13 (9.8) |

| Subjects with imputed value for end‐of‐treatment body weight | 93 (24.0) | 271 (22.1) | 238 (29.4) | 177 (16.4) | 82 (20.7) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; exenatide ER, exenatide extended release; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; IGlar, insulin glargine; N, number of subjects; SD, standard deviation.

Values are mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated.

A total of 3899 (99.5%) subjects were exposed to their investigational product and 92.5% to 95.7% completed the trials (whether they were on or off the trial medication). Overall, the proportions of subjects who discontinued treatment prematurely were 10.6% to 13.5% in the semaglutide 0.5 mg group, 12.2% to 20.3% in the semaglutide 1.0 mg group, and 7.2% to 21.0% across the comparator groups (Table 1). Premature treatment discontinuations across SUSTAIN 1, 2, 4 and 5 were comparable (12.2% to 15.3% for semaglutide 1.0 mg and 7.2% to 10.9% for comparators), while the rates in SUSTAIN 3 were numerically higher (20.3% and 21.0%, respectively).

Baseline characteristics were broadly similar between subjects across treatment groups (Table 1), with differences between trials reflecting the eligibility criteria. Baseline age and BMI were similar across the five trials. Differences in diabetes duration were observed, which reflected the stage the subjects were at in the continuum of type 2 diabetes care.

3.2. Change from baseline in body weight and related endpoints

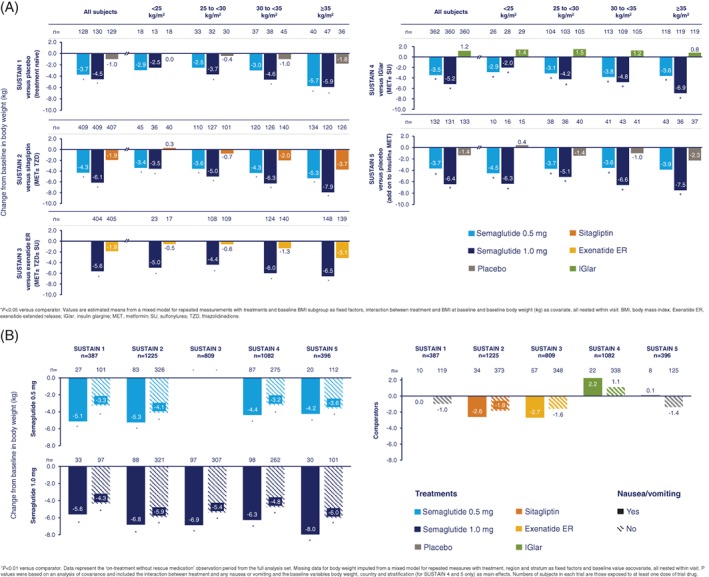

Across the SUSTAIN trials, semaglutide consistently and significantly reduced body weight from baseline versus comparators in subjects receiving different background medications (Figure 1A).15, 16, 17, 18, 19 The effect was consistent across all BMI subgroups; body weight decreased by 2.5 to 5.7 kg and 2.0 to 7.9 kg with semaglutide 0.5 and 1.0 mg, respectively, versus a 1.5 kg gain to a 3.7 kg loss with comparators (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Absolute change from baseline in body weight by BMI (A) and change in body weight from baseline by nausea or vomiting (B) across the SUSTAIN 1 to 5 trials

In general, greater absolute weight loss in kg was observed in subjects with higher baseline BMI for both semaglutide doses as well as for comparators, with the exception of insulin glargine in SUSTAIN 4. In this trial, the weight increase for insulin glargine was independent of baseline BMI, whereas the weight loss for semaglutide 1.0 mg was BMI‐dependent, leading to a significant interaction (P = .0046). There was no significant interaction between BMI and treatment difference with other comparators. Weight loss with semaglutide 1.0 mg was consistently greater than with comparators across all BMI subgroups, with the differences statistically significant in all but one case (P < .05; Figure 1A). Weight loss with semaglutide 0.5 mg was also consistently and significantly greater than with comparators across all subgroups, apart from a few cases where statistical significance was not reached (P < .05; Figure 1A).

3.3. Proportion of subjects achieving ≥5% or ≥10% weight loss

As previously reported in the individual SUSTAIN 1 to 5 trials,15, 16, 17, 18, 19 a significantly greater proportion of semaglutide‐treated subjects achieved ≥5% and ≥10% weight loss versus comparators (Figure S1, Supporting Information). Significantly greater proportions of subjects achieved weight loss ≥5% and ≥10% with both semaglutide doses versus comparators across all BMI subgroups (P < .05; Figure S1, Supporting Information). This effect was more marked with semaglutide 1.0 mg than with 0.5 mg.

The differences in subjects achieving ≥10% weight loss reached statistical significance in most BMI subgroups for semaglutide 1.0 mg, but less consistently for semaglutide 0.5 mg (Figure S1B, Supporting Information). In SUSTAIN 1, the difference in subjects achieving this weight loss response was not significant.

Among heavier subjects (baseline BMI ≥35 kg/m2), the proportions achieving ≥5% weight loss were 30% to 49% and 47% to 68% of those receiving semaglutide 0.5 and 1.0 mg, respectively, versus 6% to 27% receiving comparator treatments. These results were broadly similar to the overall population and to those with a baseline BMI <25 kg/m2, with the exception of SUSTAIN 3 (10% threshold) and SUSTAIN 5 (5% and 10% thresholds), in which proportionately fewer subjects achieved these targets than in those with low baseline BMI (Figure S1, Supporting Information). There were, however, no overall BMI‐dependent effects on relative weight loss across the trials.

3.4. Weight loss by GI AEs—post hoc analysis

Across the SUSTAIN 1 to 5 trials, 15.2% to 24.0% and 21.5% to 27.2% of subjects experienced nausea or vomiting with semaglutide 0.5 and 1.0 mg, respectively, versus 6.0% to 14.1% with comparators. Regardless of any reported events of nausea or vomiting, weight loss was consistently greater with semaglutide versus comparators (all P < .01; Figure 1B). Overall, nausea and vomiting events were mostly transient, with a median duration of between 1 and 8 days with the semaglutide 0.5 and 1.0 mg and comparator groups. The median duration of nausea events was higher with semaglutide 0.5 and 1.0 mg (15 to 33 days) versus placebo (8 days) in SUSTAIN 5.

Weight loss was generally more pronounced in subjects who experienced nausea or vomiting compared with those who did not experience such events. With semaglutide 0.5 mg, a weight change of −4.2 to −5.3 kg was reported in subjects experiencing nausea or vomiting versus −3.2 to −4.1 kg in those not experiencing these events. With semaglutide 1.0 mg, the reported weight change was −5.6 to −8.0 kg in subjects experiencing nausea and/or vomiting versus −4.3 to −6.0 kg in those not experiencing these events. The corresponding weight change values for comparator treatments were −2.7 to +2.2 kg and −1.8 to +1.1 kg for subjects with or without nausea and/or vomiting, respectively (Figure 1B).

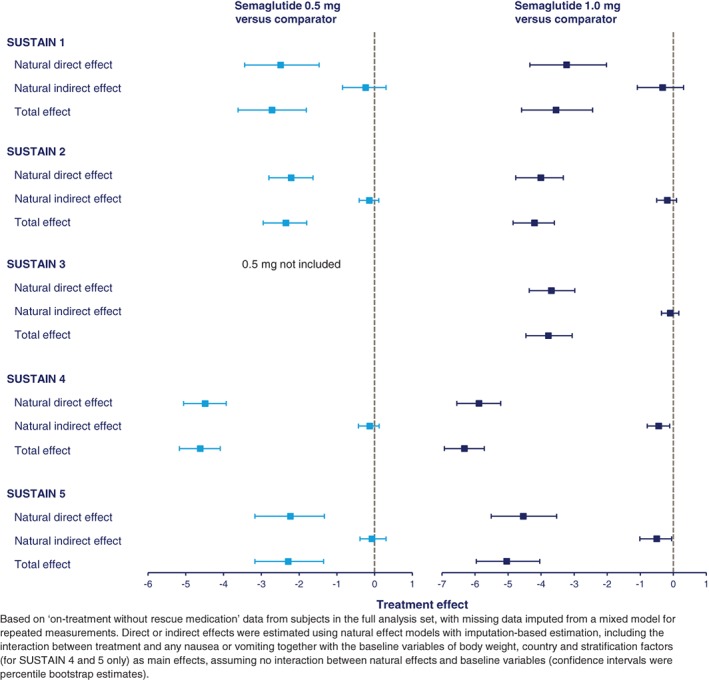

3.5. Direct and indirect effects on weight loss—mediation analysis

The mediation analyses of direct and indirect effects revealed that only a very small proportion (0.07 to 0.5 kg) of weight loss was explained by nausea or vomiting (indirect effects) (Figure 2). Therefore, of the overall greater weight loss observed with semaglutide versus comparators (2.3 to 6.3 kg), most of this reduction (2.2 to 5.9 kg) was not explained by nausea or vomiting (direct effects) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mediation analysis of direct and indirect (gastrointestinal adverse events) effects on weight loss for subjects treated with semaglutide 0.5 and 1.0 mg

3.6. Safety

Overall, semaglutide was well tolerated across the SUSTAIN 1 to 5 trials, and no unexpected safety issues were identified.15, 16, 17, 18, 19

GI AEs were generally reported at higher rates with semaglutide than with comparators, and higher rates were observed in the subgroups with comparatively lower, rather than higher, baseline BMI (Table 2). Rates of premature treatment discontinuation with semaglutide were also higher in subjects with lower baseline BMI compared with those with a higher baseline BMI (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adverse events by baseline BMI (pooled data from SUSTAIN 1 to 5 trials)

| Semaglutide 0.5 mg | Semaglutide 1.0 mg | Comparator | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | N | (%) | E | R | Number of subjects | N | (%) | E | R | Number of subjects | N | (%) | E | R | |

| Adverse events (any grade) | |||||||||||||||

| <25 kg/m2 | 99 | 71 | (71.0) | 341 | 438.2 | 116 | 84 | (71.7) | 383 | 414.8 | 119 | 74 | (63.4) | 215 | 241.3 |

| 25 to <30 kg/m2 | 285 | 202 | (71.0) | 847 | 384.8 | 406 | 284 | (69.8) | 1348 | 391.2 | 385 | 258 | (67.2) | 914 | 273.4 |

| 30 to <35 kg/m2 | 311 | 224 | (72.0) | 932 | 367.6 | 440 | 309 | (70.4) | 1236 | 327.1 | 471 | 329 | (69.6) | 1291 | 306.8 |

| ≥35 kg/m2 | 335 | 234 | (69.8) | 1009 | 370.5 | 470 | 337 | (71.8) | 1598 | 388.0 | 457 | 319 | (69.7) | 1333 | 328.5 |

| Serious adverse events | |||||||||||||||

| <25 kg/m2 | 99 | 4 | (3.9) | 10 | 11.9 | 116 | 2 | (1.8) | 3 | 3.6 | 119 | 3 | (2.7) | 3 | 3.6 |

| 25 to <30 kg/m2 | 285 | 16 | (5.6) | 20 | 9.1 | 406 | 26 | (6.5) | 34 | 9.9 | 385 | 21 | (5.6) | 28 | 8.5 |

| 30 to <35 kg/m2 | 311 | 25 | (8.0) | 36 | 14.1 | 440 | 31 | (7.1) | 48 | 12.7 | 471 | 28 | (5.9) | 33 | 7.9 |

| ≥35 kg/m2 | 335 | 22 | (6.5) | 40 | 14.6 | 470 | 45 | (9.6) | 52 | 12.6 | 457 | 33 | (7.2) | 40 | 9.9 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | |||||||||||||||

| <25 kg/m2 | 99 | 45 | (45.2) | 135 | 173.3 | 116 | 55 | (48.0) | 169 | 181.9 | 119 | 17 | (15.5) | 47 | 56.3 |

| 25 to <30 kg/m2 | 285 | 121 | (42.5) | 298 | 135.9 | 406 | 176 | (43.3) | 624 | 181.5 | 385 | 84 | (22.0) | 167 | 50.1 |

| 30 to <35 kg/m2 | 311 | 116 | (37.1) | 293 | 115.4 | 440 | 168 | (38.3) | 444 | 117.6 | 471 | 123 | (26.0) | 256 | 60.9 |

| ≥35 kg/m2 | 335 | 129 | (38.7) | 276 | 102.2 | 470 | 183 | (38.9) | 578 | 140.8 | 457 | 101 | (22.1) | 216 | 53.8 |

| Adverse events leading to premature treatment discontinuation | |||||||||||||||

| <25 kg/m2 | 99 | 11 | (11.7) | 16 | 22.1 | 116 | 19 | (16.5) | 22 | 25.8 | 119 | 7 | (6.5) | 16 | 20.1 |

| 25 to <30 kg/m2 | 285 | 31 | (10.9) | 53 | 24.2 | 406 | 36 | (8.9) | 67 | 19.3 | 385 | 13 | (3.4) | 22 | 6.7 |

| 30 to <35 kg/m2 | 311 | 14 | (4.5) | 22 | 8.7 | 440 | 34 | (7.8) | 50 | 13.2 | 471 | 17 | (3.5) | 23 | 5.4 |

| ≥35 kg/m2 | 335 | 11 | (3.3) | 19 | 7.1 | 470 | 30 | (6.4) | 47 | 11.3 | 457 | 12 | (2.6) | 18 | 4.5 |

| Nausea and/or vomiting adverse events | 1031 | 217 | (21.0) | ‐ | ‐ | 1434 | 346 | (24.1) | ‐ | ‐ | 1434 | 131 | (9.1) | ‐ | ‐ |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; E, number of events; N, number of subjects in the safety analysis set experiencing at least one event; R, event rate per 100 patient years. %, percentage of subjects experiencing at least one event. The % and R are the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel adjusted percentage and event rate.

4. DISCUSSION

The SUSTAIN 1 to 5 clinical trials previously demonstrated the superiority of semaglutide 0.5 and 1.0 mg once‐weekly over placebo and active comparators in inducing weight loss in subjects with type 2 diabetes.15, 16, 17, 18, 19 The post hoc analysis presented here further establishes the consistency of semaglutide‐induced weight loss, which was significantly greater than placebo (both as monotherapy and as an add‐on to basal insulin), sitagliptin, exenatide ER and insulin glargine, across all BMI subgroups. This is mirrored by similar analyses carried out on trials with other GLP‐1RAs. In trials with liraglutide (global population), exenatide and dulaglutide (Asian populations), weight loss over comparator remained significant across BMI subgroups.25, 26, 27 In the DURATION 6 trial, subjects treated with exenatide ER and liraglutide consistently experienced weight loss regardless of whether their baseline BMI was <30 or ≥30 kg/m2.27 An analysis of 6 trials in the AWARD clinical programme comparing dulaglutide with a range of comparators found that weight loss did not vary with baseline BMI.28

The magnitude of weight loss achieved with both semaglutide doses (0.5 mg, 3.5 to 4.3 kg; 1.0 mg, 4.5 to 6.4 kg) is numerically higher than that reported previously in the clinical trials of other long‐acting GLP‐1RAs (−0.4 to +2.5 kg).29, 30, 31, 32 Although comparisons of results between trials should be made with caution, a number of head‐to‐head trials between GLP‐1RAs have been completed that can place the results from the SUSTAIN programme in further perspective. In direct comparisons of GLP1‐RAs, weight loss was significantly greater with liraglutide 1.8 mg than exenatide ER, albiglutide, dulaglutide and lixisenatide, and similar to that of exenatide twice‐daily.11, 12 While a phase 3 trial comparing semaglutide and liraglutide is not currently available, phase 2 results suggest that semaglutide treatment may be expected to show equivalent or greater weight loss.33

SUSTAIN 3 was the only trial analyzed here that compared semaglutide with another GLP‐1RA.17 In addition, the recently published SUSTAIN 7 trial compared semaglutide 0.5 mg versus dulaglutide 0.75 mg and semaglutide 1.0 mg versus dulaglutide 1.5 mg, all once‐weekly.21 In both of these trials, semaglutide demonstrated significantly greater weight loss than the other two GLP‐1RAs, both in terms of absolute weight loss and the proportions of subjects achieving ≥5% weight loss. In SUSTAIN 3, the difference compared with exenatide ER was present across all BMI groups. This is despite the three agents ostensibly sharing the same mechanism of action. The reason behind these differences is unclear. In the case of exenatide ER, it may be related to its exendin‐4‐derived structure, which has a much lower amino acid sequence homology to native human GLP‐1 than semaglutide. This may confer different binding characteristics to the GLP‐1 receptor.11, 17

The safety findings were similar to those reported with semaglutide in the individual SUSTAIN 1 to 5 trials.15, 16, 17, 18, 19 In general, the GI disorder AE rate was higher with semaglutide than with comparators, with more GI AEs occurring in the lower versus higher baseline BMI subgroups. This is also in line with studies of other GLP‐1RAs, in which the most commonly reported AEs were typically GI in nature and included nausea, vomiting and diarrhea.11, 12

The relationship between nausea‐ or vomiting‐related events and semaglutide‐induced weight loss was assessed in a mediation analysis. We anticipated that the results of the analysis would help to determine the mechanisms of weight loss observed with semaglutide and other GLP‐1RA therapies and, in particular, whether nausea and vomiting are directly involved. Mediation analysis (i.e. how a third variable affects the relationship between the two other variables) is commonly used to elucidate the causal mechanism behind a treatment effect on a given outcome, separating an indirect effect mediated by a particular variable from the remaining direct effect.24, 34 We used this method to identify the specific proportion of the weight loss attributable to nausea or vomiting (termed an indirect effect). Weight loss not explained by nausea or vomiting was a consequence of a direct effect of semaglutide. The present analysis suggests that the contribution of nausea or vomiting to the overall semaglutide‐induced weight loss is very minor, negating these events as drivers of this weight loss and indicating that other primary contributors are responsible. This finding narrows the range of possible mechanisms behind the weight loss observed with semaglutide and with other long‐acting GLP‐1RAs.

The effect of GLP‐1RAs on weight loss has previously been shown to be centrally mediated, and may include a direct effect on the hypothalamus.35 Increased activation in the brain stem and proopiomelanocortin (POMC)/cocaine‐ and amphetamine‐regulated transcript (CART)‐producing neurons in the hypothalamus, and in other brain regions, is associated with controlling meal termination and decreased food intake in animal models,36, 37 although this has not been shown directly in humans. Nevertheless, these data are consistent with infusion studies with native GLP‐1 in healthy/normal weight and obese individuals, which suggest that the observed reduction in energy intake and appetite38 is not a consequence of nausea.39

A recent 12‐week placebo‐controlled trial of 30 obese adults has indicated a key role for reduced energy intake in semaglutide‐induced weight loss.40 The likely identified mechanisms were: reduced appetite and food cravings, better control of eating, and a lower preference for fatty, energy‐dense foods.40 These findings further weaken any causal association between GI‐related AEs such as nausea and vomiting and the weight loss observed with semaglutide. Furthermore, delay in gastric emptying does not appear to contribute to the weight loss associated with GLP‐1RAs. A similar role for energy intake has been suggested by non‐clinical and clinical studies with semaglutide, other GLP‐1RAs and human GLP‐1.38, 41, 42, 43

Key limitations include that as the current analyses were conducted post hoc, the individual trials were not powered for the subgroups analyzed here, nor were the type 1 error rates controlled across these many analyses. The use of post‐baseline values (GI AEs in this case) in the analyses complicates the otherwise simple causal inference from a randomized controlled clinical trial. Caution should be used in interpreting the mediator analysis, which assumes that all confounding variables have been included (baseline body weight, country and stratification factor) with no additional unmeasured confounding factors.

In summary, across the SUSTAIN 1 to 5 trials, once‐weekly s.c. semaglutide 0.5 and 1.0 mg consistently demonstrated greater weight loss, regardless of baseline BMI, versus all comparators. Only a small component (0.07 to 0.5 kg) of the total treatment difference in weight loss was explained by nausea or vomiting. In general, the AE rate was higher with semaglutide than comparators across the baseline BMI subgroups.

Supporting information

Table S1. SUSTAIN clinical trial design overview.

Figure S1. Proportion of subjects achieving ≥5% (A) and ≥10% (B) weight loss by baseline BMI.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all the participants, investigators and trial‐site staff who were involved in conducting the SUSTAIN 1 to 5 trials. We also thank Emre Yildirim MD PhD (Novo Nordisk) for his review and input to the manuscript, and Jamil Bacha PhD (AXON Communications) for medical writing and editorial assistance, who received compensation from Novo Nordisk.

Conflict of interest

B. A. has received speaking or consultancy fees from GSK, MSD, Novartis, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi. S. L. A. has received consultancy fees from Novo Nordisk. G. C. has received consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Beckton Dickinson, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lilly, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi. M. L. W. has received speaking or consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Lilly, Merck, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi; research funding for clinical trials (all paid to the institution) from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lilly, Mannkind Corporation, Medtronics, Mylan Pharmaceuticals, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi; and travel funding from AstraZeneca, Lilly, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi. J. P. H. W. has received consultancy fees (all paid into University funds) from GW Pharma, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Orexigen and Takeda; research grants for clinical trials from Janssen, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi and Takeda; and travel grants for conference attendance from Janssen and Novo Nordisk. S. B and A. G. H. are both full‐time employees of Novo Nordisk. L. A. L. has received consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lilly, GSK, Janssen, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi and Servier; and grant funding for CME activity from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lilly, Janssen, Merck, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi.

Author contributions

B. A. collected data as an investigator in some of the underlying trials, interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. S. L. A. interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. G. C. collected data as an investigator in some of the underlying trials, interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. M. L. W. interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. J. P. H. W. interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. S. B. carried out the post hoc statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. A. G. H. contributed to the study design of some of the underlying trials, interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. L. A. L. interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript.

All authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. B. A. is the guarantor of this work.

Data accessibility statement

http://clinicaltrials.gov: NCT02054897 (SUSTAIN 1), NCT01930188 (SUSTAIN 2), NCT01885208 (SUSTAIN 3), NCT02128932 (SUSTAIN 4), and NCT02305381 (SUSTAIN 5).

Clinical trial results have been posted on the European Clinical Trials Database (EudraCT: https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/search) with the following accession numbers: 2013‐000632‐94 (SUSTAIN 1), 2012‐004827‐19 (SUSTAIN 2), 2012‐004826‐92 (SUSTAIN 3), 2013‐004392‐12 (SUSTAIN 4) and 2013‐004502‐26 (SUSTAIN 5).

Ahrén B, Atkin SL, Charpentier G, et al. Semaglutide induces weight loss in subjects with type 2 diabetes regardless of baseline BMI or gastrointestinal adverse events in the SUSTAIN 1 to 5 trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:2210–2219. 10.1111/dom.13353

Funding information This study and the associated trials were supported by Novo Nordisk A/S, Denmark. The funding sources contributed to the design and conduct of the trials, the analysis and interpretation of the data, and the preparation, review and approval of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL, Anis AH. The incidence of co‐morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Poirier P, Giles TD, Bray GA, et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss: an update of the 1997 American Heart Association Scientific Statement on Obesity and Heart Disease from the Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation. 2006;113:898‐918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jung RT. Obesity as a disease. Br Med Bull. 1997;53:307‐321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Han TS, Tijhuis MA, Lean ME, Seidell JC. Quality of life in relation to overweight and body fat distribution. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1814‐1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Franz MJ, Boucher JL, Rutten‐Ramos S, VanWormer JJ. Lifestyle weight‐loss intervention outcomes in overweight and obese adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115:1447‐1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wing RR, Espeland MA, Clark JM, et al. Association of Weight Loss Maintenance and Weight Regain on 4‐Year Changes in CVD Risk Factors: the Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD) Clinical Trial. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:1345‐1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Look AHEAD Research Group . Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:145‐154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ryden L, Grant PJ, Anker SD, et al. ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre‐diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD: the Task Force on diabetes, pre‐diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and developed in collaboration with the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Eur Heart J. 2013;34:3035‐3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. American Diabetes Association . Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes‐2017. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:S1‐S135.27979885 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fox CS, Golden SH, Anderson C, et al. Update on prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus in light of recent evidence: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1777‐1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Madsbad S. Review of head‐to‐head comparisons of glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18:317‐332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Trujillo JM, Nuffer W, Ellis SL. GLP‐1 receptor agonists: a review of head‐to‐head clinical studies. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2015;6:19‐28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kapitza C, Nosek L, Jensen L, Hartvig H, Jensen CB, Flint A. Semaglutide, a once‐weekly human GLP‐1 analog, does not reduce the bioavailability of the combined oral contraceptive, ethinylestradiol/levonorgestrel. J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;55:497‐504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Marbury T, Flint A, Segel S, Lindegaard M, Lasseter K. Pharmacokinetics and tolerability of a single dose of semaglutide, a once‐weekly human GLP‐1 analog, in subjects with and without renal impairment. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2017;56:1381‐1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sorli C, Harashima SI, Tsoukas GM, et al. Efficacy and safety of once‐weekly semaglutide monotherapy versus placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 1): a double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled, parallel‐group, multinational, multicentre phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:251‐260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ahrén B, Masmiquel L, Kumar H, et al. Efficacy and safety of once‐weekly semaglutide versus once‐daily sitagliptin as an add‐on to metformin, thiazolidinediones, or both, in patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 2): a 56‐week, double‐blind, phase 3a, randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:341‐354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ahmann AJ, Capehorn M, Charpentier G, et al. Efficacy and safety of once‐weekly semaglutide versus exenatide ER in subjects with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 3): a 56‐week, open‐label, randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:258‐266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aroda VR, Bain SC, Cariou B, et al. Efficacy and safety of once‐weekly semaglutide versus once‐daily insulin glargine as add‐on to metformin (with or without sulfonylureas) in insulin‐naive patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 4): a randomised, open‐label, parallel‐group, multicentre, multinational, phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:355‐366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rodbard HW, Lingvay I, Reed J, et al. Semaglutide added to basal insulin in type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 5): a randomised, controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018. 10.1210/jc.2018-00070 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1834‐1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pratley RE, Aroda VR, Lingvay I, et al. Semaglutide versus dulaglutide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 7): a randomised, open‐label, phase 3b trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:275‐286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. European Medicines Agency . International Conference on Harmonisation Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6(R2). 2009. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500002874.pdf. Accessed May 29, 2018.

- 23. World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191‐2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vansteelandt S, Bekaert M, Lange T. Imputation strategies for the estimation of natural direct and indirect effects. Epidemiol Methods. 2012;1:131‐158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Buse JB, Nauck M, Forst T, et al. Exenatide once weekly versus liraglutide once daily in patients with type 2 diabetes (DURATION‐6): a randomised, open‐label study. Lancet. 2013;381:117‐124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ji L, Onishi Y, Ahn CW, et al. Efficacy and safety of exenatide once‐weekly vs exenatide twice‐daily in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig. 2013;4:53‐61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hamano K, Nishiyama H, Matsui A, Sato M, Takeuchi M. Efficacy and safety analyses across 4 subgroups combining low and high age and body mass index groups in Japanese phase 3 studies of dulaglutide 0.75 mg after 26 weeks of treatment. Endocr J. 2017;64:449‐456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Umpierrez GE, Pantalone KM, Kwan AY, Zimmermann AG, Zhang N, Fernández Landó L. Relationship between weight change and glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes receiving once‐weekly dulaglutide treatment. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18:615‐622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Umpierrez G, Tofe Povedano S, Perez Manghi F, Shurzinske L, Pechtner V. Efficacy and safety of dulaglutide monotherapy versus metformin in type 2 diabetes in a randomized controlled trial (AWARD‐3). Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2168‐2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Russell‐Jones D, Cuddihy RM, Hanefeld M, et al. Efficacy and safety of exenatide once weekly versus metformin, pioglitazone, and sitagliptin used as monotherapy in drug‐naive patients with type 2 diabetes (DURATION‐4): a 26‐week double‐blind study. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:252‐258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Garber A, Henry R, Ratner R, et al. Liraglutide versus glimepiride monotherapy for type 2 diabetes (LEAD‐3 Mono): a randomised, 52‐week, phase III, double‐blind, parallel‐treatment trial. Lancet. 2009;373:473‐481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nauck MA, Stewart MW, Perkins C, et al. Efficacy and safety of once‐weekly GLP‐1 receptor agonist albiglutide (HARMONY 2): 52 week primary endpoint results from a randomised, placebo‐controlled trial in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequately controlled with diet and exercise. Diabetologia. 2016;59:266‐274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nauck MA, Petrie JR, Sesti G, et al. A phase 2, randomized, dose‐finding study of the novel once‐weekly human GLP‐1 analog, semaglutide, compared with placebo and open‐label liraglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:231‐241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. MacKinnon D. An Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Secher A, Jelsing J, Baquero AF, et al. The arcuate nucleus mediates GLP‐1 receptor agonist liraglutide‐dependent weight loss. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:4473‐4488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Campos CA, Bowen AJ, Schwartz MW, Palmiter RD. Parabrachial CGRP neurons control meal termination. Cell Metab. 2016;23:811‐820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Betley JN, Cao ZF, Ritola KD, Sternson SM. Parallel, redundant circuit organization for homeostatic control of feeding behavior. Cell. 2013;155:1337‐1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Edwards CM, Stanley SA, Davis R, et al. Exendin‐4 reduces fasting and postprandial glucose and decreases energy intake in healthy volunteers. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;281:E155‐E161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Naslund E, Barkeling B, King N, et al. Energy intake and appetite are suppressed by glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) in obese men. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23:304‐311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Blundell J, Finlayson G, Axelsen MB, et al. Effects of once‐weekly semaglutide on appetite, energy intake, control of eating, food preference and body weight in subjects with obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19:1242‐1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rolin B, Larsen MO, Christoffersen BO, Lau J, Knudsen LB. In vivo effect of semaglutide in pigs supports its potential as a long‐acting GLP‐1 analogue for once‐weekly dosing. Diabetes. 2015;64:1119. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Horowitz M, Flint A, Jones KL, et al. Effect of the once‐daily human GLP‐1 analogue liraglutide on appetite, energy intake, energy expenditure and gastric emptying in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;97:258‐266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Flint A, Raben A, Astrup A, Holst JJ. Glucagon‐like peptide 1 promotes satiety and suppresses energy intake in humans. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:515‐520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. SUSTAIN clinical trial design overview.

Figure S1. Proportion of subjects achieving ≥5% (A) and ≥10% (B) weight loss by baseline BMI.

Data Availability Statement

http://clinicaltrials.gov: NCT02054897 (SUSTAIN 1), NCT01930188 (SUSTAIN 2), NCT01885208 (SUSTAIN 3), NCT02128932 (SUSTAIN 4), and NCT02305381 (SUSTAIN 5).

Clinical trial results have been posted on the European Clinical Trials Database (EudraCT: https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/search) with the following accession numbers: 2013‐000632‐94 (SUSTAIN 1), 2012‐004827‐19 (SUSTAIN 2), 2012‐004826‐92 (SUSTAIN 3), 2013‐004392‐12 (SUSTAIN 4) and 2013‐004502‐26 (SUSTAIN 5).