Abstract

Considerable data has been generated to elucidate the transcriptional response of cells to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) exposure providing a mechanistic understanding of UVR‐induced cellular responses. However, using these data to support standards development has been challenging. In this study, we apply benchmark dose (BMD) modeling of transcriptional data to derive thresholds of gene responsiveness following exposure to solar‐simulated UVR. Human epidermal keratinocytes were exposed to three doses (10, 20, 150 kJ/m2) of solar simulated UVR and assessed for gene expression changes 6 and 24 hr postexposure. The dose‐response curves for genes with p‐fit values (≥ 0.1) were used to derive BMD values for genes and pathways. Gene BMDs were bi‐modally distributed, with a peak at ∼16 kJ/m2 and ∼108 kJ/m2 UVR exposure. Genes/pathways within Mode 1 were involved in cell signaling and DNA damage response, while genes/pathways in the higher Mode 2 were associated with immune response and cancer development. The median value of each Mode coincides with the current human exposure limits for UVR and for the minimal erythemal dose, respectively. Such concordance implies that the use of transcriptional BMD data may represent a promising new approach for deriving thresholds of actinic effects. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 59:502–515, 2018. © 2018 The Authors Environmental and Molecular Mutagenesis published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc. on behalf of Environmental Mutagen Society

Keywords: benchmark dose, ultraviolet radiation, keratinocytes, solar simulated, genomics

INTRODUCTION

Global interest in the use of transcriptional profiling for risk assessment has led to the development of new high‐throughput analytical approaches to assess dose‐response [Yang et al., 2007; Kuo et al., 2016]. However, although substantial amounts of transcriptional data have been generated in the UVR field, the data have been predominantly used to support an understanding of mechanistic effects. These studies have shown that UVR exposure (particularly in the UVB spectrum) can induce changes in gene expression and pathways associated with adverse health effects [Becker et al., 2001; Li et al., 2001; Murakami et al., 2001; Sesto et al., 2002; Takao et al., 2002; Enk et al., 2004]. Most in vitro studies have also shown that UV exposure can induce apoptosis in cells and cause a strong and persistent induction in the expression of oncogenes such as c‐myc and c‐jun [He et al., 2004]. Similarly, studies using solar‐simulated UVR exposure have demonstrated differential gene expression associated with apoptosis, cell growth arrest, and cytokines [Marrot et al., 2005, 2010; Kaneko et al., 2008]. However, translating lists of time‐ and dose‐dependent differentially expressed genes into meaningful information to support risk assessment has remained a challenge.

Over the past decade, software has been developed to analyze genomic data to derive benchmark doses (BMDs) of effects [Yang et al., 2007]. BMD modeling was first developed by Crump [1984] and is now being applied by the US Environmental Protection Agency [US EPA, 2012] for conventional risk assessment. A BMD represents the dose at which a predefined increase above background (in most applications selected as 10% or one standard deviation [Slob, 2017]) occurs in a dose‐response experiment for the endpoint under investigation. A variety of mathematical models are applied, and the model that best fits the data is selected to identify the BMD [Yang et al., 2007; US EPA, 2012]. This approach is preferred over the selection of a no (or lowest) observed effects level because it is not tied to the selection of a dose used in the experiment (rather it extrapolates the predefined response from the curve). BMD modeling of global transcriptomic data can be done in a high‐throughput manner through the use of the BMDExpress software [Yang et al., 2007]. This package allows the user to model and apply filters to derive both individual gene and pathway (or other gene groups) BMDs. Pathway BMDs are generally represented as the mean or median BMD of responding genes within a pathway, with some criteria applied (e.g., significant enrichment of this pathway or a minimum number of genes that yield BMDs within the pathway). The approach has been widely applied in chemical toxicology and case studies have shown a high degree of correlation between gene/pathway BMDs and BMDs for conventional endpoints [e.g., Bhat et al., 2013; Jackson et al., 2014; Dean et al., 2017; Farmahin et al., 2017]. Thus, transcriptional BMDs have been proposed as points of departure for use in human health risk assessment [Thomas et al., 2013; Moffat et al., 2015].

Recently, by using case examples in the ionizing radiation field, we have shown the possibility of using BMDs as thresholds of effects for genes and pathways that are well established radiation responders (e.g., p53, cell cycle regulation, and so forth) [Chauhan et al., 2016]. Indeed, we posit that BMD modeling of transcriptional datasets provides an opportunity to provide relevant mechanistic and quantitative information on the dose‐response relationship to support decision‐making in the field of ionizing radiation following further targeted validation studies.

To explore this application in more detail, in this study we performed BMD modeling on transcription response data from human‐derived skin cells exposed to solar‐simulated UVR. Human keratinocytes were exposed to solar‐simulated UVR at three environmentally‐relevant doses, and cells were harvested following a 6‐ or 24 hr incubation period. Global gene expression profiling was performed using Illumina microarray technology. Statistically significant expressed gene probes, as assessed by one‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA), were subjected to BMD modeling. BMD based values for genes and pathways were derived and a quantitative threshold, based on the median distribution of these genes, was obtained for solar‐simulated UVR‐exposed cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All solutions were prepared with 18 MΩ water (Milli‐Q plus PF unit, Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA). Cells were detached from the culture dishes by trypsinization (Trypsin/EDTA, Cascade Biologics), followed by neutralization (Trypsin Neutralizer, Cascade Biologics).

Cell Maintenance

Neonatal epidermal keratinocytes (HEKn, cat # C‐001‐5C) were purchased from Cascade Biologics (Portland, OR), and cultured at 37°C (5% CO2) in complete medium [EpiLife® basal medium supplemented with calcium chloride, PSA solution, and HKGD growth kit (Cascade Biologics)]. About 7.5 × 104 cells were transferred into each 60 mm2 dishes containing 5 mL of complete media and cultured until 60–70% confluence. Prior to irradiation in the solar simulator the cells were washed once with sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.4, and covered with a layer of PBS (5 mL) to prevent drying.

Ultraviolet‐Radiation Exposure

Solar simulated UVR exposure was performed using an in‐house Oriel solar simulator (Stratford, CT) equipped with a 1,600 W Xenon short arc lamp with an Oriel Air Mass 1 Direct Filter, (AM1:D:B; model 81074), calibrated to mimic a typical summer solar irradiance in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada (latitude 45°25′N). A KG2 Short Pass Filter was also placed between the cell culture and the source to limit excessive infrared transmission. The average spectral irradiance over an area of 17 × 17 cm was found to be 9.84 mW/cm2 for UVA (98.3%), 0.174 mW/cm2 for UVB (1.7%), and 10 mW/cm2 (0.017 mW/cm2 erythemally‐weighted) for the total UVR irradiance at an emission rate of 0.1 kJ/m2·sec, which was determined using a spectroradiometer (Optronics Laboratories, Model 754‐C) and integrating the area under the curve between 280 and 400 nm. For comparison, the solar irradiance measured in Ottawa on July 14, 2011 at 11:15 am was 5.30 mW/cm2 for UVA (95.5%), 0.252 mW/cm2 for UVB (4.5%), and 5.55 mW/cm2 (0.019 mW/cm2, erythemally‐weighted) for the total UVR irradiance. Keratinocyte cultures grown in 60 mm petri dishes were placed 186 mm from the solar simulator lamp where they received a dose of either 0, 10, 20, or 150 kJ/m2 of unweighted UVR and were maintained at 37°C using a temperature‐controlled water bath and a customized water circulation system. The UVR doses used in this study were based upon UVR doses applied in a separate study and were therefore not ideal for a proper BMD analysis; however these results still demonstrate the promise of BMD modeling to assessing point‐of‐departure of genes/pathways in response to UVR. The erythemally‐weighted equivalence of the unweighted dose is displayed in the following table (Table 1).

Table 1.

Treatment Dose and its Erythemally‐Weighted Equivalence

| Unweighted UVR dose | CIEa‐erythema weighted UV dose (kJ/m2) | Minimal erythemal dose |

|---|---|---|

| (kJ/m2) | (kJ/m2) | (MED) |

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 0.017 | 0.068 |

| 20 | 0.034 | 0.14 |

| 150 | 0.2545 | 1.01 |

| 1 MED = 0.25 kJ/m2 weighted |

ISO 17166:1999/CIE S007‐1998.

The CIE‐erythema weighted UV dose, also known as the effective dose or erythemal dose, is calculated with the erythemal effective irradiance (E eff) as a function of exposure time of t seconds.

The erythemal effective irradiance (E eff) from a source of ultraviolet radiation is obtained by weighting the spectral irradiance of the radiation at wavelength λ in nm by the effectiveness of radiation of this wavelength to cause a minimal erythema and summing over all wavelengths (250–400 nm) present in the source spectrum and is defined by the equation:

where Eλ is the spectral irradiance in W⋅m−2 ⋅ nm−1 and S(λ) is the weighting factor determined in accordance with the CIE‐erythema reference action spectrum.

Following exposure to sham or solar‐simulated UVR, cultures were placed back into a 37°C incubator and were harvested 6‐ or 24 hr postexposure for RNA isolation. The sham samples were handled identically and concurrently with UVR‐treated samples, but they received no UVR exposure. A total of six independent experiments were conducted, with each experiment containing samples exposed to a sham‐control and three doses of UVR for each time point (6‐ or 24 hr).

RNA Extraction/Hybridization

Following treatment, keratinocytes within 60 mm culture dishes were washed with PBS and replaced with Qiagen's RLT lysis buffer containing 2‐Mercaptoethanol (Qiagen) and immediately frozen in a −80°C freezer. Frozen lysates were later thawed and pipetted onto a QIAshredder spin column, and total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini kits according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen). During the procedure, Qiagen's On‐Column RNase‐free DNase was used to eliminate possible DNA contamination. RNA concentration was evaluated using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (ThermoScientific) and RNA integrity was confirmed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer with RNA 6000 PicoChip kits (Agilent Technologies), following the manufacturer's instructions (Agilent Technologies, Mississauga, ON). Only high quality RNA (OD 260/280 ≥ 1.8, RIN ≥ 7.0) was used for analysis of differential gene expression.

Total RNA (150 ng) from each sample was used to generate biotin‐labeled cRNA following the Illumina TotalPrep 96 RNA Amplification Kit (Ambion). Agilent's Low RNA Input Fluorescent Linear Amplification Kit was used to generate fluorescently‐labeled cRNA, from the total RNA, following the manufacturer's protocol (Agilent Technologies, Mississauga, ON). The mRNA from the total RNA was primed with the (d)T‐T7 primer and amplified using MMLV‐reverse transcriptase into (5′to 3′) cDNA. Cyanine‐3 labeled (3′ to 5′) cRNA was generated from the cDNA, using T7 RNA polymerase and isolated using the Qiagen's RNeasy Mini kit following the manufacturer's protocol (Qiagen).

For each sample, 1.5 μg of biotin‐labeled cRNA was hybridized onto Illumina Human HT‐12 V3.0 expression BeadChips (human3) (Illumina), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The Illumina BeadChips were imaged and quantified with the Illumina iScan scanner (Illumina) and data were processed with Illumina GenomeStudio v2010.2 software. Data processing included averaging signal intensities for each beadtype, quantile normalization, and log2‐transformation. All expression values were first log2 transformed to minimize skews in the data and provides more realistic variation measures. Quantile normalization was applied to impose the same empirical distribution across all the samples [Bolstad et al., 2003]. Briefly, a reference array of empirical quantiles is first computed by taking the average across all ordered samples. The original expression values are then replaced by the entries of the reference array with the same rank.

BMD Modeling

Datasets were normalized and genes were modeled and imported into BMDExpress (version 1.41) software [Yang et al., 2007]. A built‐in one‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test with P‐value ≤ 0.05 was used to determine differentially expressed genes as recommended by Webster et al. [2015]. Thereafter, gene probes exhibiting a significant change in expression in at least one dose point were modeled using all available best‐fit models (which included the Hill, Power, Linear, and 2° Polynomial models) to identify potential dose‐response relationships. For each dataset of statistically significant gene probe expressions, the maximum degree of polynomial models applied was dependent upon the number of radiation doses (excluding control) minus one. A best‐fit model was selected based on the following criteria: First, a nested chi‐square test was performed with a cutoff of 0.05 to choose between Linear and Polynomial models. Next, between the Hill, Power, Linear and Polynomial models, the least complex model was selected with the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Finally, a best‐fit model needed to have a goodness‐of‐fit P‐value ≥ 0.1. A Hill model was flagged if the k parameter of the model was less than one‐third of the lowest positive dose. In the case where a flagged Hill model was selected as the best‐fit model based on the above criteria, the next best model with goodness‐of‐fit P‐value ≥ 0.05 was selected. In the case where the next best model with P‐value ≥ 0.05 was not available, the flagged Hill model was retained and modified to 0.5 of the lowest nonflagged Hill BMD value. Other parameters for modeling included power restricted to 1, maximum iterations of 250, confidence interval of 0.95, and benchmark response value of 1.349, which approximates a 10% change and is the default value in BMDExpress software [Yang et al., 2007] as defined in Thomas et al., 2007.

Using the built‐in Defined Category Analysis feature of BMDExpress, the remaining probes that demonstrated dose‐response characteristics, that passed the selection criteria described above, were mapped to Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (downloaded on December 15, 2015). Probes annotated to more than one gene (promiscuous probes) were removed from further analysis, as were probes yielding BMD values higher than the highest dose and a goodness‐of‐fit P‐value ≤ 0.1. Only probes that met the data acceptance criteria were retained.

BMDExpress Data Viewer Parameters

Export files from BMDExpress were uploaded to BMDExpress Data Viewer [Kuo et al., 2016] for visualization of gene BMD, pathway BMD mean/median, and model distributions. Dataset Exploratory Tools, including Functional Enrichment Analysis and Multiple Dataset Comparison were used for data analyzes. For each dataset the default settings provided by the software were applied. This included the removal of genes with BMD/BMDL (lower 95% confidence limit) ratio ≥ 2. Lastly, BMDExpress Data Viewer determined the appropriate bin sizes using Google Chart's histogram implementation.

RESULTS

Probe Modeling

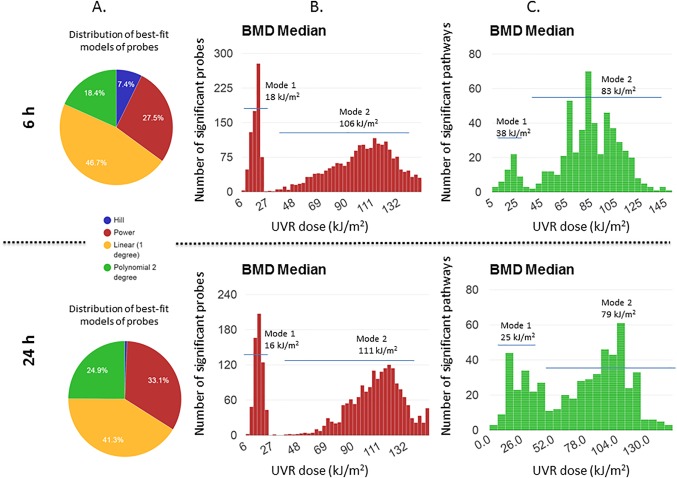

A graphical representation to illustrate the distribution of best‐fit models generated by BMDExpress software for statistically significant ANOVA filtered dose‐responsive probes, for the 6 hr and 24 hr time‐points are depicted in Figure 1. A large portion of the probes fit a linear model (46.7% for 6 hr and 41.3% for 24 hr) (Fig. 1A, Table 2). As illustrated in Figure 1B, the BMD histogram of filtered probe data demonstrated two distinct modes of response, with Mode 1 ranging from 0 to 27 kJ/m2 and Mode 2 ranging from 38 to 150 kJ/m2. Pathway analysis of the probes comprising each mode was conducted for the 6 hr time‐point (Table 3). In general, Mode 1 comprised pathways involved in cell signaling and DNA damage response, while pathways in Mode 2 shared similar responses but were also broadly associated with immune response and developmental processes such as cancer. The 24 hr time‐point yielded similar pathways, but with a lower percentage of mapped genes (Supporting Information Table S1). The median BMD values of each mode was found to be ∼16 kJ/m2 for Mode 1 and ∼108 kJ/m2 for Mode 2 at both time‐points (Table 2). The median distribution across all probes was 94.4 kJ/m2 for the 6 hr time‐point and 101.9 kJ/m2 for the 24 hr time‐point (Table 2).

Figure 1.

BMD summary outputs (A) 6 and 24 hr pie charts plotted to illustrate the distribution of best‐fit models selected by BMDExpress for the statistically significant UV‐responsive gene probes (B) BMD probe distribution (C) BMD median pathway distribution.

Table 2.

BMD Summary Statistics

| Time‐point | BMD probe median | Mode 1 BMD Median | Mode 2 BMD Median | BMD pathway median | Best‐fit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (h) | (kJ/m2) | (0–27 kJ/m2) | (28–150 kJ/m2) | (kJ/m2) | (Model) |

| 6 | 94.41 | 17.97 | 105.63 | 83.37 | linear |

| 24 | 101.94 | 15.86 | 111.17 | 80.25 | linear |

Table 3.

BMD Pathway Modal Analysis for 6 hr Post Irradiation

| Mode 1 (dose: 0–27 kJ/m2) | P value | Genes |

|---|---|---|

| Role of macrophages, fibroblasts and endothelial cells in rheumatoid arthritis | 2.57 E –02 | MAPK1,PIK3R1,CREBBP,WNT2B,CSNK1A1,VEGFC,IKBKE,JAK2,IRAK3,PDGFB,PRKCZ,NLK,CREB1,CHUK,TRAF5,RYK,IRAK2 |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia signaling | 5.37 E –03 | CDKN2A,E2F4,HDAC4,MAPK1,PIK3R1,CTBP2,IKBKE,CHUK,CBLC |

| Xenobiotic metabolism signaling | 1.02 E –02 | HDAC4,MAPK1,PPP2R2A,PIK3R1,CREBBP,HS2ST1,GSTT1,PRKCZ,GSTT2/GSTT2B,ALDH3A2,SULT1A1,NCOA1,CHST11,PPP2R5C,HS3ST1,UGT2B11,SCAND1 |

| Protein ubiquitination pathway | 3.72 E –02 | PSMA6,UBE2Q1,HLA‐A,PSMC4,ANAPC10,UBE4A,SKP2,UBE2D4,UBE2D2,PSMB2,PSMD12,HSPB11,ANAPC11,PSMC3,UBE2C |

| iNOS signaling | 7.24 E –04 | MAPK1,CREBBP,IKBKE,CHUK,JAK2,IRAK3,IRAK2 |

| RAR activation | 6.92 E –03 | CSNK2A1,ARID1A,MAPK1,PIK3R1,CDK7,CREBBP,GTF2H2,JAK2,PRKCZ,TRIM24,BRD7,PRKAR1B,NCOA1,SCAND1 |

| PI3K/AKT signaling | 1.05 E –02 | MAPK1,INPP5F,GAB1,PPP2R2A,PIK3R1,IKBKE,PPP2R5C,CHUK,JAK2,PRKCZ |

| Cyclins and cell cycle regulation | 1.95 E –02 | CDKN2A,E2F4,HDAC4,PPP2R2A,CDK7,PPP2R5C,SKP2 |

| Mitotic roles of polo‐like kinase | 6.76 E –03 | PLK4,PPP2R2A,ANAPC10,PKMYT1,PLK1,PPP2R5C,ANAPC11 |

| IGF‐1 signaling | 7.08 E –03 | IGFBP6,CSNK2A1,CASP9,MAPK1,PIK3R1,PRKAR1B,JAK2,SOCS5,PRKCZ |

| HIPPO signaling | 1.05 E –02 | CSNK1E,DLG5,PPP2R2A,FRMD6,PPP2R5C,STK3,PRKCZ,SKP2 |

| Role of CHK proteins in cell cycle checkpoint control | 1.29 E –02 | E2F4,PPP2R2A,PLK1,PPP2R5C,RAD50,NBN |

| Heparan sulfate biosynthesis | 1.29 E –02 | XYLT1,SULT1A1,HS2ST1,CHST11,EXTL3,HS3ST1 |

| Heparan sulfate biosynthesis (late stages) | 2.69 E –02 | SULT1A1,HS2ST1,CHST11,EXTL3,HS3ST1 |

| Nucleotide excision repair pathway | 3.16 E –02 | ERCC1,CDK7,GTF2H2,RAD23B |

| Pancreatic adenocarcinoma signaling | 3.47 E –02 | CDKN2A,E2F4,CASP9,MAPK1,PIK3R1,VEGFC,JAK2,NOTCH1 |

| mTOR signaling | 5.62 E –02 | MAPK1,PPP2R2A,RPS27,PIK3R1,PRR5,VEGFC,PPP2R5C,RICTOR,RPS29,PRKCZ,RPS24 |

| Role of RIG1‐like receptors in antiviral innate immunity | 5.62 E –02 | CREBBP,IKBKE,CHUK,TRIM25 |

| Mode 2 (Dose: 30–150 kJ/m2) | P value | Genes |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular mechanisms of cancer | 8.15 E –03 | FYN,RAPGEF1,RELA,RALA,ARHGEF7,PIK3R1,BMP2,PSEN2,CDKN2B,PTK2,CDC25B,NFKBIA,WNT7A,RHOT1,WNT7B,PIK3C3,E2F5,GSK3B,BRCA1,HIPK2,BIRC3,RALGDS,BMP1,PMAIP1,ARHGEF4,PRKCQ,GNA12,RALB,SMAD7,FZD9,MDM2,AURKA,GNAI3,FZD8,FOS,CDKN2D,PRKCI,MAX,CBL,CDKN1A,PRKCH,FNBP1,LRP1 |

| Factors promoting cardiogenesis in vertebrates | 3.63 E –02 | NODAL,PRKCQ,MYL2,TGFBR3,BMP2,FZD9,TCF7L1,FZD8,PRKCI,PRKCH,NPPA,GSK3B,TCF7L2,LRP1,BMP1 |

| Role of NFAT in regulation of the immune response | 2.14 E –02 | RELA,FYN,PRKCQ,CD79B,NFATC3,PIK3R1,CD4,GNA12,CSNK1A1,CD79A,GNAI3,CALM1 (includes others),RCAN1,IKBKB,FOS,CD3G,LCK,NFKBIA,PLCG2,PIK3C3,LAT,ZAP70,LYN,IKBKAP,GSK3B |

| NRF2‐mediated oxidative stress response | 1.32 E –02 | USP14,PIK3R1,MAF,GCLC,DNAJB2,MAFG,HMOX1,AKR1A1,PIK3C3,DNAJC8,GSK3B,GCLM,GSTM1,PRKCQ,DNAJC19,HERPUD1,JUNB,MAFF,DNAJC21,FOS,PRKCI,ACTA2,PRKCH,MAPK7,DNAJB6,SQSTM1,CDC34,ABCC4 |

| Fc? receptor‐mediated phagocytosis in macrophages and monocytes | 4.68 E –02 | FYN,PRKCQ,PIK3R1,INPP5D,MYO5A,PLD4,PLA2G6,HMOX1,CBL,ARPC1A,PRKCI,ACTA2,LYN,PRKCH,ARPC4 |

| Protein ubiquitination pathway | 1.70 E –02 | USP14,CDC20,HSPB2,HSPA6,DNAJB2,USP2,TCEB1,UBE2F,USP48,USO1,USP8,DNAJC8,USP16,USP47,BRCA1,ANAPC11,BIRC3,NEDD4,USP36,DNAJC19,PSMD6,MDM2,USP1,SKP2,UCHL3,DNAJC21,DNAJC24,CBL,UBE2H,HLA‐C,CUL2,UBE2G1,UBE2E2,CRYAA/LOC102724652,SMURF2,CDC34,DNAJB6 |

| PKC? signaling in T lymphocytes | 2.57 E –02 | RELA,FYN,PRKCQ,NFATC3,PIK3R1,CD4,MALT1,FOS,IKBKB,CD3G,LCK,NFKBIA,PLCG2,PIK3C3,LAT,ZAP70,MAP3K3,MAP3K2 |

| CD28 signaling in T helper cells | 2.57 E –02 | RELA,FYN,PRKCQ,NFATC3,CD4,PIK3R1,MALT1,FOS,IKBKB,CALM1 (includes others),CD3G,LCK,ARPC1A,NFKBIA,PIK3C3,LAT,ZAP70,ARPC4 |

| T cell receptor signaling | 1.41 E –02 | RELA,FYN,PRKCQ,NFATC3,CD4,PIK3R1,MALT1,FOS,IKBKB,CALM1 (includes others),CD3G,LCK,CBL,NFKBIA,PIK3C3,LAT,ZAP70 |

| Autophagy | 1.55 E –04 | ATG4C,ATG5,ULK1,VPS18,ATG9A,VPS16,ATG4B,PIK3C3,ATG4A,MAP1LC3B,SQSTM1,VPS11 |

| Regulation of IL‐2 expression in activated and anergic T lymphocytes | 4.47 E –02 | IKBKB,FYN,CALM1 (includes others),CD3G,RELA,FOS,NFKBIA,NFATC3,PLCG2,LAT,ZAP70,TOB1,MALT1 |

| Hereditary breast cancer signaling | 1.58 E –02 | PBRM1,PIK3R1,TUBG1,BARD1,RFC1,DDB2,FANCL,CCNB1,RAD51,BRD7,MSH2,GADD45A,RFC4,SMARCA2,PIK3C3,CDKN1A,XPC,RFC2,BRCA2,BRCA1,RFC3 |

| p53 signaling | 4.07 E –02 | PMAIP1,TP53INP1,TOPBP1,PIK3R1,TNFRSF10B,MDM2,TP53I3,SCO2,GADD45A,PIK3C3,ADCK3,CDKN1A,GSK3B,HIPK2,PIDD1,BRCA1 |

| Cell cycle: G2/M DNA damage checkpoint regulation | 2.69 E –03 | CDC25B,GADD45A,YWHAE,CDKN1A,TOP2A,MDM2,AURKA,HIPK2,BRCA1,SKP2,PPM1D,CCNB1 |

| Role of BRCA1 in DNA damage response | 2.57 E –04 | PBRM1,TOPBP1,BARD1,RBBP8,ATRIP,RFC1,FANCL,RAD51,BRD7,MSH2,RFC4,GADD45A,SMARCA2,CDKN1A,E2F5,RFC2,BRCA2,BRCA1,RFC3 |

| Purine nucleotides de novo biosynthesis II | 1.38 E –02 | ADSS,ADSL,PPAT,ATIC |

| Axonal guidance signaling | 3.52 E –02 | FYN,GLI2,MYL2,ITSN1,BDNF,NFATC3,PIK3R1,ARHGEF7,BMP2,PGF,ROCK2,PTK2,SEMA6D,WNT7A,WNT7B,PIK3C3,BAIAP2,NTRK1,ADAM19,PLXNB1,PLXNB2,GSK3B,ERBB2,BMP1,PRKCQ,GNA12,EPHA1,TUBG1,TUBA4A,FZD9,L1CAM,SLIT2,GIT1,GNAI3,FZD8,PRKCI,ARPC1A,TUBB6,PLCG2,EPHB3,PRKCH,ADAM9,OPN1SW,ARPC4,NRP1 |

Functional Enrichment Analysis

Functional enrichment analysis in BMDExpress Data Viewer applies the Fisher's exact test to determine the probability that genes from a particular pathway are over‐represented in a list of DEGs by comparison the complete set of genes in an organism [Kuo et al., 2016]. Functional classification of BMDs was conducted for both time‐points as described by Kuo et al. [2016]. The BMD distributions for pathways are provided in Figure 1C. The histogram shows a bimodal response to pathway activation following solar‐simulated UVR exposure. A list of pathways exhibiting a Fisher's Exact P‐value of ≤ 0.05 with a minimum of five genes is provided in Tables 4 and 5 for the 6 and 24 hr time‐points, respectively. The pathways were sorted based on BMD values, highlighting those that were perturbed at each mode.

Table 4.

Statistically Significant Pathways Identified in the 6 hr Time‐Point and Associated BMD Values

| Pathway | BMD Median unweighted dose (kJ/m2) | Fishers exact P‐value (%) | Number of significant genes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrimidine ribonucleotides interconversion | 21.7182 | 2.13 | 6 | Mode 1 |

| Pyrimidine ribonucleotides de novo biosynthesis | 21.7182 | 3.01 | 6 | |

| Nucleotide excision repair pathway | 25.98675 | 0.5 | 8 | |

| IGF‐1 signaling | 28.3745 | 0.3 | 17 | |

| DNA double‐strand break repair by homologous recombination | 32.1586 | 0.5 | 5 | |

| Telomere extension by telomerase | 37.9528 | 0.7 | 5 | |

| Assembly of RNA polymerase II complex | 40.5364 | 1.81 | 9 | |

| IL‐15 production | 40.788 | 3.52 | 6 | |

| Estrogen receptor signaling | 41.1082 | 0.88 | 18 | |

| Amyloid processing | 48.4955 | 3.51 | 9 | |

| Cell cycle: G2/M DNA damage checkpoint regulation | 49.1606 | 0 | 17 | |

| Adipogenesis pathway | 52.3224 | 0.2 | 20 | |

| Cell cycle control of chromosomal replication | 54.57425 | 0.16 | 8 | |

| Mitotic roles of polo‐like kinase | 57.38095 | 0 | 15 | Mode 2 |

| Cyclins and cell cycle regulation | 60.2006 | 0.04 | 17 | |

| PTEN signaling | 60.2006 | 0.05 | 21 | |

| Cell cycle: G1/S checkpoint regulation | 60.2006 | 0.3 | 13 | |

| Sonic Hedgehog signaling | 61.4501 | 3.01 | 6 | |

| Small cell lung cancer signaling | 61.80105 | 0.24 | 17 | |

| Semaphorin signaling in neurons | 62.47665 | 0.97 | 10 | |

| mTOR signaling | 63.20475 | 0.16 | 26 | |

| Oxidized GTP and dGTP detoxification | 63.97375 | 0.3 | 28 | |

| PDGF signaling | 64.06025 | 1.67 | 12 | |

| IL‐17A signaling in fibroblasts | 64.1084 | 0.36 | 9 | |

| Prostate cancer signaling | 64.4782 | 0.98 | 16 | |

| ERK5 signaling | 65.3988 | 0.16 | 13 | |

| Androgen signaling | 65.3988 | 0.84 | 25 | |

| Xenobiotic metabolism signaling | 65.4632 | 0.08 | 37 | |

| 14‐3‐3‐mediated signaling | 66.0496 | 0.5 | 18 | |

| Prolactin signaling | 67.1095 | 0.03 | 16 | |

| HIPPO signaling | 67.7237085 | 0.09 | 16 | |

| NGF signaling | 68.1574 | 0.06 | 20 | |

| Antiproliferative role of TOB in T cell signaling | 68.709575 | 2.13 | 6 | |

| Role of CHK proteins in cell cycle checkpoint control | 68.729567 | 0 | 15 | |

| Cell cycle regulation by BTG family proteins | 68.729567 | 2.82 | 7 | |

| PI3K/AKT signaling | 68.7426835 | 0.06 | 24 | |

| ERK/MAPK signaling | 68.7426835 | 1.11 | 28 | |

| Pancreatic adenocarcinoma signaling | 68.7558 | 0.02 | 23 | |

| Lymphotoxin? receptor signaling | 68.7558 | 0.05 | 13 | |

| VEGF family ligand‐receptor interactions | 68.7558 | 0.07 | 15 | |

| p70S6K signaling | 68.7558 | 0.11 | 21 | |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia signaling | 68.7558 | 0.3 | 17 | |

| Angiopoietin signaling | 68.7558 | 0.34 | 13 | |

| Anti‐inflammation and pro‐apoptotic mechanisms utilized by Yersinia pestis | 68.7558 | 2.09 | 7 | |

| G?12/13 signaling | 68.7558 | 2.63 | 17 | |

| UVB‐induced MAPK signaling | 68.7558 | 3.94 | 9 | |

| IL‐2 signaling | 68.7558 | 3.94 | 9 | |

| Pyridoxal 5‐phosphate salvage pathway | 68.7558 | 4.13 | 23 | |

| p53 signaling | 69.5671 | 0.02 | 20 | |

| Fc Epsilon RI signaling | 69.95905 | 0.13 | 18 | |

| RAR activation | 70.887025 | 0.01 | 30 | |

| Fc? receptor‐mediated phagocytosis in macrophages and monocytes | 71.1623 | 0.18 | 17 | |

| D‐myo‐inositol (1,4,5)‐trisphosphate degradation | 71.1623 | 1.24 | 5 | |

| D‐myo‐inositol (1,3,4)‐trisphosphate biosynthesis | 71.1623 | 1.6 | 5 | |

| 1D‐myo‐inositol hexakisphosphate biosynthesis II (Mammalian) | 71.1623 | 1.6 | 5 | |

| Superpathway of D‐myo‐inositol (1,4,5)‐trisphosphate metabolism | 71.1623 | 4.37 | 5 | |

| Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) signaling | 71.7331 | 1.05 | 8 | |

| Mechanisms of viral exit from host cells | 72.60895 | 1.7 | 8 | |

| Ovarian cancer signaling | 72.6889 | 0.08 | 25 | |

| Wnt/?‐catenin signaling | 73.4417335 | 0.29 | 26 | |

| Transcriptional regulatory network in embryonic stem cells | 73.49585 | 1.96 | 8 | |

| Glioma signaling | 74.8883 | 0.16 | 20 | |

| Role of macrophages, fibroblasts and endothelial cells in rheumatoid arthritis | 75.479 | 0.01 | 44 | |

| Role of Wnt/GSK‐3? signaling in the pathogenesis of influenza | 75.479 | 3.17 | 12 | |

| LPS‐stimulated MAPK signaling | 76.061 | 0.47 | 14 | |

| IL‐12 signaling and production in macrophages | 76.061 | 0.54 | 18 | |

| IL‐17A signaling in airway cells | 76.061 | 1.12 | 12 | |

| Type II Diabetes mellitus signaling | 76.061 | 2.34 | 20 | |

| Effect of Bacillus anthracis toxins on macrophage function | 76.061 | 3.43 | 20 | |

| HGF signaling | 76.761775 | 2.3 | 18 | |

| PI3K signaling in B lymphocytes | 77.26425 | 0.02 | 24 | |

| SAPK/JNK signaling | 77.640775 | 1.77 | 16 | |

| Virus entry via endocytic pathways | 78.16795 | 1.72 | 14 | |

| Filoviral‐mediated alteration of cytokine production in innate immune responses | 78.27815 | 0.47 | 14 | |

| Role of pattern recognition receptors in recognition of bacteria and viruses | 78.94095 | 1.06 | 16 | |

| VDR/RXR activation | 79.41495 | 0.63 | 14 | |

| NRF2‐mediated oxidative stress response | 79.7547 | 0 | 37 | |

| Gap junction signaling | 79.7547 | 1.55 | 21 | |

| CTLA4 signaling in cytotoxic T lymphocytes | 81.2194 | 0.41 | 15 | |

| eNOS signaling | 81.5021 | 2.04 | 18 | |

| Molecular mechanisms of cancer | 81.77585 | 0.01 | 60 | |

| Glucocorticoid receptor signaling | 82.2928 | 0.01 | 42 | |

| Glioma invasiveness signaling | 82.5309 | 4.52 | 9 | |

| Heparan sulfate biosynthesis | 82.7629 | 0.27 | 24 | |

| Heparan sulfate biosynthesis (late stages) | 82.7629 | 0.58 | 22 | |

| Dopamine‐DARPP32 feedback in cAMP signaling | 82.8046335 | 3.53 | 22 | |

| Production of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species in macrophages | 82.8388 | 0 | 30 | |

| PPAR signaling | 82.90845 | 0.26 | 16 | |

| Mitochondrial dysfunction | 83.3275 | 4.86 | 19 | |

| iNOS signaling | 83.3662 | 0.01 | 13 | |

| B cell receptor signaling | 83.3662 | 0.09 | 27 | |

| Antioxidant action of vitamin C | 83.3662 | 0.1 | 15 | |

| Induction of apoptosis by HIV1 | 83.3662 | 0.16 | 13 | |

| IL‐8 signaling | 83.3662 | 0.22 | 29 | |

| Protein Kinase A signaling | 83.3662 | 0.39 | 39 | |

| CD27 signaling in lymphocytes | 83.3662 | 0.59 | 11 | |

| RANK signaling in osteoclasts | 83.3662 | 1.15 | 15 | |

| TWEAK signaling | 83.3662 | 2.44 | 7 | |

| 4‐1BB signaling in T lymphocytes | 83.46785 | 0.61 | 8 | |

| Cholecystokinin/Gastrin‐mediated signaling | 83.5016 | 4.54 | 14 | |

| ILK signaling | 83.69635 | 0.03 | 30 | |

| RhoA signaling | 84.63145 | 0.54 | 18 | |

| Role of BRCA1 in DNA damage response | 84.76775 | 0 | 21 | |

| Hereditary breast cancer signaling | 84.76775 | 0.01 | 23 | |

| ATM signaling | 84.76775 | 0.08 | 13 | |

| Aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling | 84.76775 | 0.4 | 23 | |

| AMPK signaling | 84.76775 | 0.46 | 27 | |

| Tec kinase signaling | 84.86515 | 1.93 | 24 | |

| NF‐?B activation by viruses | 85.2828 | 0.04 | 16 | |

| G?q signaling | 85.8799 | 0.07 | 26 | |

| April mediated signaling | 85.8799 | 1.7 | 8 | |

| IL‐3 signaling | 85.89915 | 1.53 | 12 | |

| Tight junction signaling | 86.3458 | 2.49 | 23 | |

| CD40 signaling | 86.4234 | 1.12 | 12 | |

| Insulin receptor signaling | 86.4285 | 0.13 | 21 | |

| Role of JAK2 in hormone‐like cytokine signaling | 86.4285 | 1.77 | 7 | |

| GDNF family ligand‐receptor interactions | 86.4285 | 2.81 | 11 | |

| Role of osteoblasts, osteoclasts and chondrocytes in rheumatoid arthritis | 86.43295 | 0.6 | 30 | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus signaling | 86.56875 | 0.16 | 28 | |

| CDP‐diacylglycerol biosynthesis I | 86.85785 | 0.16 | 6 | |

| Phosphatidylglycerol biosynthesis II (Nonplastidic) | 86.85785 | 0.22 | 6 | |

| NF‐?B signaling | 86.86975 | 0.28 | 24 | |

| T cell receptor signaling | 87.1994 | 0.01 | 21 | |

| Natural killer cell signaling | 87.1994 | 3.32 | 15 | |

| Hypoxia signaling in the cardiovascular system | 88.3084 | 0.48 | 12 | |

| Role of NFAT in regulation of the immune response | 88.3936 | 0.01 | 31 | |

| PKC? signaling in T lymphocytes | 88.3936 | 0.37 | 23 | |

| B cell activating factor signaling | 88.3936 | 0.74 | 9 | |

| Colorectal cancer metastasis signaling | 89.4806 | 0.8 | 33 | |

| MIF‐mediated glucocorticoid regulation | 89.4806 | 1.49 | 7 | |

| Estrogen‐mediated S‐phase Entry | 89.508075 | 1.45 | 6 | |

| JAK/Stat signaling | 89.585875 | 3.17 | 12 | |

| Integrin signaling | 89.7925 | 2.82 | 26 | |

| Protein ubiquitination pathway | 90.1604 | 0 | 36 | |

| Serotonin degradation | 90.3392 | 3.98 | 10 | |

| Breast cancer regulation by Stathmin1 | 90.823725 | 1.17 | 26 | |

| Regulation of IL‐2 expression in activated and Anergic T lymphocytes | 91.6453 | 0.21 | 16 | |

| Induction of apoptosis by Francisella tularensis | 94.3216 | 0.41 | 15 | |

| Erythropoietin signaling | 95.8156 | 0.13 | 14 | |

| Sphingosine‐1‐phosphate signaling | 96.1025 | 0.98 | 16 | |

| Human embryonic stem cell pluripotency | 96.431 | 4.74 | 21 | |

| D‐myo‐inositol (3,4,5,6)‐tetrakisphosphate biosynthesis | 96.8797 | 0.01 | 43 | |

| D‐myo‐inositol (1,4,5,6)‐Tetrakisphosphate biosynthesis | 96.8797 | 0.01 | 43 | |

| 3‐phosphoinositide degradation | 96.8797 | 0.01 | 43 | |

| 3‐phosphoinositide biosynthesis | 96.8797 | 0.01 | 45 | |

| Phospholipase C signaling | 96.8797 | 0.04 | 37 | |

| Superpathway of inositol phosphate compounds | 97.9458 | 0.01 | 48 | |

| iCOS‐iCOSL Signaling in T helper cells | 98.3293 | 1.83 | 16 | |

| MIF regulation of innate immunity | 98.8728 | 1.7 | 8 | |

| D‐myo‐inositol‐5‐phosphate metabolism | 99.0119 | 0 | 45 | |

| Axonal guidance signaling | 99.172 | 0.23 | 53 | |

| Autophagy | 99.25395 | 0 | 14 | |

| p38 MAPK signaling | 99.822 | 1.27 | 17 | |

| Thrombopoietin signaling | 99.86325 | 0.14 | 12 | |

| Stearate biosynthesis I (Animals) | 100.69505 | 1.05 | 30 | |

| Basal cell carcinoma signaling | 100.948 | 4.52 | 11 | |

| Mismatch repair in eukaryotes | 101.06645 | 0.16 | 6 | |

| Endothelin‐1 signaling | 101.237 | 0.63 | 22 | |

| TREM1 signaling | 102.0385 | 3.14 | 10 | |

| Apoptosis signaling | 106.4305 | 2.2 | 14 | |

| Factors promoting cardiogenesis in vertebrates | 106.848 | 0.42 | 16 | |

| CD28 signaling in T Helper cells | 108.265 | 0.05 | 21 | |

| TNFR2 signaling | 108.265 | 1.03 | 7 | |

| Death receptor signaling | 108.4875 | 0.7 | 16 | |

| TNFR1 signaling | 108.4875 | 0.72 | 10 | |

| Neuropathic pain signaling in dorsal horn neurons | 109.432 | 2.64 | 15 | |

| Epithelial adherens junction signaling | 109.6895 | 1.93 | 20 | |

| Melatonin signaling | 111.394 | 4.88 | 11 | |

| Corticotropin releasing hormone signaling | 111.457 | 1.98 | 20 | |

| Purine nucleotides De Novo biosynthesis II | 113.154 | 0.08 | 5 | |

| Growth hormone signaling | 113.298 | 0.64 | 13 | |

| Oleate biosynthesis II (Animals) | 116.092 | 1.77 | 7 | |

| Calcium‐induced T lymphocyte apoptosis | 116.749 | 2.39 | 10 |

Table 5.

Statistically Significant Pathways Identified in the 24 hr Time‐Point and Associated BMD Analysis

| Pathway | BMD Median unweighted dose (kJ/m2) | Fishers exact P‐value (%) | Number of significant genes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrimidine deoxyribonucleotides de novo biosynthesis I | 19.3256 | 0 | 8 | Mode 1 |

| Pyrimidine ribonucleotides interconversion | 19.3923 | 3.72 | 5 | |

| Pyrimidine ribonucleotides de novo biosynthesis | 19.3923 | 4.93 | 5 | |

| Methionine degradation I (to Homocysteine) | 19.5567 | 0.03 | 13 | |

| Cysteine biosynthesis III (mammalia) | 19.5567 | 0.04 | 13 | |

| Superpathway of methionine degradation | 19.5567 | 0.17 | 13 | |

| Autophagy | 28.7172 | 1.39 | 7 | |

| Superpathway of cholesterol biosynthesis | 30.2143 | 1.16 | 6 | |

| Role of Oct4 in mammalian embryonic stem cell pluripotency | 30.304 | 1.5 | 8 | |

| GADD45 signaling | 34.8245 | 1 | 5 | |

| ATM signaling | 37.6877 | 0.06 | 12 | |

| Triacylglycerol biosynthesis | 42.8107 | 0.54 | 15 | Mode 2 |

| Glutaryl‐CoA degradation | 42.8107 | 0.82 | 9 | |

| p53 signaling | 45.029 | 2.93 | 13 | |

| Small cell lung cancer signaling | 51.444075 | 4.26 | 12 | |

| Estrogen‐mediated S‐phase Entry | 55.7718 | 2.71 | 5 | |

| Pancreatic adenocarcinoma signaling | 55.7718 | 2.83 | 15 | |

| Role of CHK Proteins in cell cycle checkpoint control | 58.0174 | 0 | 14 | |

| Cell cycle control of chromosomal replication | 58.82865 | 0.05 | 8 | |

| Mismatch repair in eukaryotes | 60.263 | 0.45 | 5 | |

| Role of BRCA1 in DNA damage response | 60.263 | 0.62 | 11 | |

| Hereditary breast cancer signaling | 61.87215 | 0.13 | 18 | |

| Tryptophan degradation III (Eukaryotic) | 65.0471 | 0.76 | 10 | |

| Ovarian cancer signaling | 68.27525 | 4.93 | 17 | |

| Cell cycle: G2/M DNA damage checkpoint regulation | 71.9505 | 0 | 16 | |

| Bladder cancer signaling | 74.4811 | 0.04 | 18 | |

| Stearate biosynthesis I (Animals) | 75.53915 | 0.09 | 30 | |

| Signaling by Rho family GTPases | 76.6873 | 4.68 | 26 | |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis signaling | 82.84405 | 2.22 | 14 | |

| Axonal guidance signaling | 83.8447 | 3.32 | 41 | |

| Pyridoxal 5‐phosphate salvage pathway | 85.6785 | 1.18 | 22 | |

| Cell cycle: G1/S checkpoint regulation | 86.711125 | 2.47 | 10 | |

| Salvage pathways of pyrimidine ribonucleotides | 87.4168 | 0.15 | 27 | |

| Endothelin‐1 signaling | 91.03745 | 2.11 | 18 | |

| Cyclins and cell cycle regulation | 92.25125 | 0 | 18 | |

| Mitotic roles of polo‐like kinase | 94.0146 | 0 | 21 | |

| Remodeling of epithelial adherens junctions | 94.7878 | 3.77 | 9 | |

| Adipogenesis pathway | 95.9394 | 0.98 | 16 | |

| Eicosanoid signaling | 97.73305 | 1.15 | 8 | |

| ILK signaling | 98.95675 | 1.18 | 22 | |

| Phospholipases | 99.41165 | 0.25 | 10 | |

| Inhibition of matrix metalloproteases | 104.7145 | 0.53 | 8 | |

| Ubiquinol‐10 biosynthesis (eukaryotic) | 106.365 | 1.69 | 17 | |

| Telomerase signaling | 108.175 | 4.48 | 12 | |

| Melatonin degradation I | 110.125 | 4.66 | 9 | |

| Glycolysis I | 111.4 | 2.71 | 5 |

In general, solar‐simulated UVR exposure induced pathways involved in nucleotide metabolism, cell cycle control, cell signaling, DNA damage response, and apoptosis. This response was consistent at both time‐points after exposure, but was somewhat attenuated at 24 hr postexposure (data not shown). Twenty‐four pathways and 468 probes were common between the two time‐points (data not shown). Unique pathways and probes were also identified between the two time‐points; however, no further analysis was conducted on these datasets. BMD median values for the common pathways were generally higher for the 6 hr postexposure time‐point (Table 6). Seven out of the 24 genes demonstrated BMD median values that were higher for the 24 hr time‐point relative to the 6 hr time‐point. These genes were mostly involved in cell cycle regulation, cell differentiation, or cell signaling. Functional Enrichment Analysis of Fisher Exact P‐values (≤ 0.05) vs BMD median values was used to identify pathways that were potentially important for the mode of action of solar‐simulated UVR exposure (Supporting Information Table S2). This analysis identified pathways related to molecular mechanisms of cancer and axonal guidance signaling, with BMD median values between 81 and 99 kJ/m2, to be the most responsive to solar simulated UVR. The same two pathways were also sustained at 24 hr postexposure (data not shown). The lowest pathway BMD in the overall dataset was pyrimidine deoxyribonucleotide de novo biosynthesis I, with a BMD of 19.3 kJ/m2, and eight genes with BMDs at 24 hr.

Table 6.

Common Pathways Between 6 and 24 hr and Associated BMD Values

| BMD median unweighted dose (kJ/m2) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pathway | 6 hr | 24 hr |

| Pyrimidine ribonucleotides de novo biosynthesis | 21.7182 | 19.3923 |

| Pyrimidine ribonucleotides interconversion | 21.7182 | 19.3923 |

| Cell Cycle: G2/M DNA damage checkpoint regulation | 49.1606 | 71.9505 |

| Adipogenesis pathway | 52.3224 | 95.9394 |

| Cell cycle control of chromosomal replication | 54.57425 | 58.82865 |

| Mitotic roles of polo‐like kinase | 57.38095 | 94.0146 |

| Cell Cycle: G1/S checkpoint regulation | 60.2006 | 86.711125 |

| Cyclins and cell cycle regulation | 60.2006 | 92.25125 |

| Small cell lung cancer signaling | 61.80105 | 51.444075 |

| Role of CHK proteins in cell cycle checkpoint control | 68.729567 | 58.0174 |

| Pancreatic adenocarcinoma signaling | 68.7558 | 55.7718 |

| Pyridoxal 5‐phosphate salvage pathway | 68.7558 | 85.6785 |

| p53 signaling | 69.5671 | 45.029 |

| Ovarian cancer signaling | 72.6889 | 68.27525 |

| ILK signaling | 83.69635 | 98.95675 |

| ATM signaling | 84.76775 | 37.6877 |

| Role of BRCA1 in DNA damage response | 84.76775 | 60.263 |

| Hereditary breast cancer signaling | 84.76775 | 61.87215 |

| Estrogen‐mediated S‐phase Entry | 89.508075 | 55.7718 |

| Axonal guidance signaling | 99.172 | 83.8447 |

| Autophagy | 99.25395 | 28.7172 |

| Stearate biosynthesis I (Animals) | 100.69505 | 75.53915 |

| Mismatch repair in eukaryotes | 101.06645 | 60.263 |

| Endothelin‐1 signaling | 101.237 | 91.03745 |

DISCUSSION

With the advent of genomic technologies, the throughput of detecting molecular changes has dramatically increased employing bioinformatic techniques to predict precursors of more profound biological changes. Recent papers suggest that the application of BMD modeling to transcriptional data offers significant advantages over traditional genomic bioinformatics approaches [Farmahin et al., 2017]. BMD modeling of transcriptomic data provides more quantitative information on threshold gene and pathway responses (e.g., point‐of‐departure), simpler interpretation of large datasets, and allows direct comparison to other data with similar endpoints without the need to have matched doses to increase threshold prediction accuracy [Webster et al., 2015]. In this study, we present the first analysis of gene responsiveness to solar‐simulated UVR using BMD modeling.

BMD modeling requires experimental data at a minimum of three doses across a broad range. In our test example, keratinocytes were exposed to a low, medium or high dose of UVR (0, 10, 20, 150 kJ/m2). At 6 and 24 hr postexposure, cells were harvested and assessed for transcriptional changes using BMD modeling. The data displayed a bi‐modal distribution at both 6 and 24 hr postexposure for both individual transcripts and pathways. The majority of the transcripts demonstrated a linear trend‐line, implying that solar‐simulated UVR exposure induced a dose‐responsive change in gene expression. For both time‐points the median BMD values for Modes 1 and 2 were ∼16 kJ/m2 and ∼108 kJ/m2, respectively. Although the meaning of this bi‐modal response is unclear, this finding is consistent with our previous analysis of BMD responses using ionizing radiation (X‐rays and alpha particles) [Chauhan et al., 2016]. It is likely that these modes reflect different mechanisms and toxicological effects that are being induced at different doses, and should thus provide meaningful insight in the effects of the exposure. To explore this in more detail, we performed pathway analysis of genes observed within each mode.

At 6 hr postexposure in Mode 1 (3–27 kJ/m2) we observed transcriptional changes in cell cycle regulation pathways, presumably associated with induction of DNA repair mechanisms. Studies have shown that within this dose range, cells have capacity to repair damage without leading to propagation of gross morphological damage [Pontén et al., 1995; Young et al., 1996, 1998; Heenen et al., 2001; Chang et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2013]. With higher doses of UVR (Mode 2), we observed transcriptional changes in DNA repair pathways, but also the activation of pathways related to cancer development, suggesting that above this dose there is a transition to perturbations in transcripts involved in a variety of processes and functions that are altered in cancer cells. This is also reflected in transcriptional changes in pathways associated with activation of cellular apoptosis and immune response. At 24 hr postexposure, a similar bi‐modal response was observed, supporting the mechanism‐based information derived from the modal analysis.

At 24 hr postexposure in Mode 1 (2–27 kJ/m2), transcriptionally activated pathways were predominately associated with nucleotide biosynthesis, with a few effectors involved in cell cycle signaling. At the higher dose range (Mode 2), pathways involved in cell signaling and cell cycle regulation were activated, while cancer‐promoting pathways were also still prominent. Interestingly, we also observed that genes involved in DNA repair pathways were transcriptionally altered, indicating that the DNA damage response persisted despite the long postexposure incubation time, possibly resulting from UVA‐induced DNA damage. It has been shown that repair mechanisms for UVA are less efficient and that the damage may persist several hours after exposure [Tadokoro et al., 2003; Agar and Young, 2005].

Twenty‐four pathways in both modes at the 24 hr time point were also found in the 6 hr time point in the same modes (Table 6). These pathways involved DNA damage recognition, pyrimidine metabolism, and cell cycle regulation. Interestingly, some unexpected pathways also appeared to be common across the two time‐points, including endothelin signaling and axonal guidance signaling at the higher dose range (Mode 2). These responses are consistent with previous publications demonstrating that UVR exposure can cause activation of mutagenic repair dimers, recombination repair, and cell‐cycle checkpoint regulation and apoptosis, as activated through the ATR kinase pathway [Brown and Baltimore, 2003]. A comparison of the BMD medians for these pathways showed the majority to have lower BMD values for the 24 hr time‐point relative to the 6 hr time‐point, possibly highlighting a time‐dependency in pathway activation.

Li et al. [2001] reported time‐dependency of UVB‐induced gene expression changes as they observed three waves involving early (0.5–2 hr), intermediate (4–8 hr), and late (16–24 hr) stages of gene expression. Early expression changes were associated with transcription factors such as c‐myc and c‐fos, mitochondrial proteins like cytochromes c and b, and changes in phosphorylation states with altered expression of either kinases or phosphatases, responding to the immediate damage. Whereas, cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors dominated the intermediate wave, particularly the neutrophil chemotactic and melanocyte activator interleukin 8, most of which are involved in the erythemal process. Genes induced at the late stage were predominately differentiation markers involved in the protective cornified envelope of the skin.

Human maximum permissible exposure (MPE) limits for UVR (by wavelength) have been previously developed for both the eye and skin by the International Commission on Non‐Ionizing Radiation Protection [ICNIRP, 2004]. These MPE's have been implemented by the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) in their standard IEC‐62471 (2006) “Photobiological safety of lamps and lamp systems” to establish an actinic exposure limit for broadband UVR (200 to 400 nm) for unprotected skin and the eye for an 8 hr period of 0.03 kJ/m2(erythemally‐weighted). It is interesting to note that the median from Mode one, found in the current study, coincided with the ICNIRP MPE limit.

Previous studies have shown cellular responses can occur at exposure levels below the MPE limit. Pontén et al. [1995] demonstrated upregulated expression of p53 and p21 in an in vivo study using broadband UVR at a dose of ∼0.03 kJ/m2 as soon as 4 hr post exposure. Similarly, Huang et al. [2013] reported an increase in nuclear p53 in keratinocytes at 3 hr postexposure to ∼0.03 kJ/m2 as a result of oxidative stress with minor cytotoxicity. The authors postulated that p53 played a role as a transcriptional repressor by downregulating a number of proteins that may result in photo‐aging effects. Interestingly, in this study, we found that the median of Mode 1 response corresponded to a dose of ∼0.03 kJ/m2 (unweighted UVR irradiance of ∼16 kJ/m2). The probes/pathways expressed at this dose were involved in cell signaling and DNA damage response, despite the lack of effect on apoptosis or decline in cellular viability (data not shown). Overall, our data show that stressor signaling in keratinocytes occurred at the actinic exposure limit (8 hr) of international standards designed to limit acute adverse effects (e.g., erythema).

Small increases in the exposure level above the actinic exposure limit (0.03 kJ/m2) have been reported to initiate dramatic cellular responses. Eberlein‐König et al. [1998] reported that exposure to UVB (0.05 kJ/m2, erythemally‐weighted) was able to significantly increase the inflammatory cytokines IL‐1α and IL‐6 24 hr postirradiation. At 0.1 kJ/m2 UVR (erythemally‐weighted), Köck et al. [1990] showed UVR could initiate the release of the inflammatory and pro‐apoptotic cytokine TNF‐α from human keratinocytes. Similarly, other studies have found that UVR can induce apoptosis and cellular death in keratinocytes in this dose range [Chang et al., 2002, 2003; Kang et al., 2011]. In the current study, the median BMD value for Mode 2 (∼108 kJ/m2 unweighted, ∼0.184 kJ/m2 erythemally‐weighted) coincided with the dose required to cause minimal erythema to an individual with a type I fair skin type (0.2 kJ/m2 = 1 Minimum Erythemal Dose (MED) or 2 Standard Erythemal Dose (SED)).

This preliminary work shows the potential of BMD modeling of transcriptional data to support point‐of‐departure assessment of molecular responses to UVR exposure. Although promising, additional studies/datasets are required to assess a larger assortment of dose ranges, exposure conditions, time‐lines and cell lines/tissues to ensure the consistency of the results prior to comparison of thresholds derived from conventional methods to current exposure limits to UVR. In addition, the current BMD methodology used for chemical risk assessment, which is at more advanced stages of implementation, may need to be refined for its appropriate applicability to UVR exposure. The additional value is that genomic data from any study with similar experimental procedures can be added to the analysis building on the weight of evidence with mechanistic data to support decision‐making. In all, the study suggests a potential use of BMD modeling of transcriptome data to determine biologically‐relevant thresholds of UVR responses.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Qutob designed the study and conducted the experimental work and data collection. Dr. Chauhan and Mr. Kuo performed the data analysis, and provided statistics. Dr. Qutob prepared the manuscript with significant intellectual input from Drs. Chauhan, Yauk, McNamee and Mr. Kuo.

Supporting information

Supporting Information 1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank Anne Haegert and Robert Bell of the Vancouver Prostate Centre Microarray Facility (Vancouver, Canada) for their expertise in conducting the Illumina microarray hybridization, scanning and analysis within this study. This study was funded by Health Canada's Genomics Research & Development Initiative (GRDI) Phase IV (2008–2011).

REFERENCES

- Agar N, Young AR. 2005. Melanogenesis: A photoprotective response to DNA damage?. Mutat Res 571:121–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker B, Vogt T, Landthaler M, Stolz W. 2001. Detection of differentially regulated genes in keratinocytes by cDNA array hybridization: Hsp27 and other novel players in response to artificial ultraviolet radiation. J Invest Dermatol 116:983–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat VS, Hester SD, Nesnow S, Eastmond DA. 2013. Concordance of transcriptional and apical benchmark dose levels for conazole‐induced liver effects in mice. Toxicol Sci 136:205–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. 2003. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics 19:185–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EJ, Baltimore D. 2003. Essential and dispensable roles of ATR in cell cycle arrest and genome maintenance. Genes Dev 17:615–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H, Sander CS, Müller CS, Elsner P, Thiele JJ. 2002. Detection of poly(ADP‐ribose) by immunocytochemistry: A sensitive new method for the early identification of UVB‐ and H2O2‐induced apoptosis in keratinocytes. Biol Chem 383:703–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H, Oehrl W, Elsner P, Thiele JJ. 2003. The role of H2O2 as a mediator of UVB‐induced apoptosis in keratinocytes. Free Radic Res 37:655–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan V, Kuo B, McNamee JP, Wilkins RC, Yauk CL. 2016. Transcriptional benchmark dose modeling: Exploring how advances in chemical risk assessment may be applied to the radiation field. Environ Mol Mutagen 57:589–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump KS. 1984. An improved procedure for low‐dose carcinogenic risk assessment from animal data. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol 5:339–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean JL, Zhao QJ, Lambert JC, Hawkins BS, Thomas RS, Wesselkamper SC. 2017. Editor's highlight: Application of gene set enrichment analysis for identification of chemically induced, biologically relevant transcriptomic networks and potential utilization in human health risk assessment. Toxicol Sci 157:85–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberlein‐König B, Jäger C, Przybilla B. 1998. Ultraviolet B radiation‐induced production of interleukin 1alpha and interleukin 6 in a human squamous carcinoma cell line is wavelength‐dependent and can be inhibited by pharmacological agents. Br J Dermatol 139:415–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enk CD, Shahar I, Amariglio N, Rechavi G, Kaminski N, Hochberg M. 2004. Gene expression profiling of in vivo UVB‐irradiated human epidermis. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 20:129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmahin R, Williams A, Kuo B, Chepelev NL, Thomas RS, Barton‐Maclaren TS, Curran IH, Nong A, Wade MG, Yauk CL. 2017. Recommended approaches in the application of toxicogenomics to derive points of departure for chemical risk assessment. Arch Toxicol 91:2045–2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He YY, Huang JL, Sik RH, Liu J, Waalkes MP, Chignell CF. 2004. Expression profiling of human keratinocyte response to ultraviolet A: Implications in apoptosis. J Invest Dermatol 122:533–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heenen M, Giacomoni PU, Golstein P. 2001. Individual variations in the correlation between erythemal threshold, UV‐induced DNA damage and sun‐burn cell formation. J Photochem Photobiol B 63:84–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang HC, Chang TM, Chang YJ, Wen HY. 2013. UVB irradiation regulates ERK1/2‐ and p53‐dependent thrombomodulin expression in human keratinocytes. PLoS One 8:e67632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Icnirp . 2004. Guidelines on limits of exposure to ultraviolet radiation of wavelengths between 180 nm and 400 nm (Incoherent Optical Radiation). Health Phys 87:171–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AF, Williams A, Recio L, Waters MD, Lambert IB, Yauk CL. 2014. Case study on the utility of hepatic global gene expression profiling in the risk assessment of the carcinogen furan. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 274:63–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko K, Smetana‐Just U, Matsui M, Young AR, John S, Norval M, Walker SL. 2008. cis‐Urocanic acid initiates gene transcription in primary human keratinocytes. J Immunol 181:217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang ES, Iwata K, Ikami K, Ham SA, Kim HJ, Chang KC, Lee JH, Kim JH, Park SB, Kim JH, et al. 2011. Aldose reductase in keratinocytes attenuates cellular apoptosis and senescence induced by UV radiation. Free Radic Biol Med 50:680–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köck A, Schwarz T, Kirnbauer R, Urbanski A, Perry P, Ansel JC, Luger TA. 1990. Human keratinocytes are a source for tumor necrosis factor alpha: Evidence for synthesis and release upon stimulation with endotoxin or ultraviolet light. J Exp Med 172:1609–1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo B, Francina Webster A, Thomas RS, Yauk CL. 2016. BMDExpress Data Viewer ‐ a visualization tool to analyze BMDExpress datasets. J Appl Toxicol 36:1048–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Turi TG, Schuck A, Freedberg IM, Khitrov G, Blumenberg M. 2001. Rays and arrays: The transcriptional program in the response of human epidermal keratinocytes to UVB illumination. FASEB J 15:2533–2535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrot L, Belaïdi JP, Jones C, Perez P, Meunier JR. 2005. Molecular responses to stress induced in normal human caucasian melanocytes in culture by exposure to simulated solar UV. Photochem Photobiol 81:367–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrot L, Planel E, Ginestet AC, Belaïdi JP, Jones C, Meunier JR. 2010. In vitro tools for photobiological testing: Molecular responses to simulated solar UV of keratinocytes growing as monolayers or as part of reconstructed skin. Photochem Photobiol Sci 9:448–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffat I, Chepelev N, Labib S, Bourdon‐Lacombe J, Kuo B, Buick JK, Lemieux F, Williams A, Halappanavar S, Malik A, et al. 2015. Comparison of toxicogenomics and traditional approaches to inform mode of action and points of departure in human health risk assessment of benzo[a]pyrene in drinking water. Crit Rev Toxicol 45:1–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami T, Fujimoto M, Ohtsuki M, Nakagawa H. 2001. Expression profiling of cancer‐related genes in human keratinocytes following non‐lethal ultraviolet B irradiation. J. Dermatol Sci 27:121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontén F, Berne B, Ren ZP, Nistér M, Pontén J. 1995. Ultraviolet light induces expression of p53 and p21 in human skin: Effect of sunscreen and constitutive p21 expression in skin appendages. J Invest Dermatol 105:402–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesto A, Navarro M, Burslem F, Jorcano JL. 2002. Analysis of the ultraviolet B response in primary human keratinocytes using oligonucleotide microarrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:2965–2970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slob W. 2017. A general theory of effect size, and its consequences for defining the benchmark response (BMR) for continuous endpoints. Crit Rev Toxicol 47:342–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadokoro T, Kobayashi N, Zmudzka BZ, Ito S, Wakamatsu K, Yamaguchi Y, Korossy KS, Miller SA, Beer JZ, Hearing VJ. 2003. UV‐induced DNA damage and melanin content in human skin differing in racial/ethnic origin. FASEB J 17:1177–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takao J, Ariizumi K, Dougherty II, Cruz PD. Jr. 2002. Genomic scale analysis of the human keratinocyte response to broad‐band ultraviolet‐B irradiation. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 18:5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas RS, Allen BC, Nong A, Yang L, Bermudez E, Clewell HJ, Andersen ME. 2007. A method to integrate benchmark dose estimates with genomic data to assess the functional effects of chemical exposure. Toxicol Sci 98:240–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas RS, Philbert MA, Auerbach SS, Wetmore BA, Devito MJ, Cote I, Rowlands JC, Whelan MP, Hays SM, Andersen ME, et al. 2013. Incorporating new technologies into toxicity testing and risk assessment: Moving from 21st century vision to a data‐driven framework. Toxicol Sci 136:4–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US EPA . 2012. Benchmark Dose Technical Guidance (EPA/100/R‐12/001). https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-01/documents/benchmark_dose_guidance.pdf Accessed 10 May 2017.

- Webster AF, Chepelev N, Gagné R, Kuo B, Recio L, Williams A, Yauk CL. 2015. Impact of genomics platform and statistical filtering on transcriptional benchmark doses (BMD) and multiple approaches for selection of chemical point of departure (PoD). PLoS One 10:e0136764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Allen BC, Thomas RS. 2007. BMDExpress: A software tool for the benchmark dose analyses of genomic data. BMC Genomics 8:387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AR, Chadwick CA, Harrison GI, Hawk JL, Nikaido O, Potten CS. 1996. The in situ repair kinetics of epidermal thymine dimers and 6‐4 photoproducts in human skin types I and II. J Invest Dermatol 106:1307–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AR, Chadwick CA, Harrison GI, Nikaido O, Ramsden J, Potten CS. 1998. The similarity of action spectra for thymine dimers in human epidermis and erythema suggests that DNA is the chromophore for erythema. J Invest Dermatol 111:982–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information 1