Abstract

Background

Decreasing anastomotic leak rates remain a major goal in colorectal surgery. Assessing intraoperative perfusion by indocyanine green (ICG) with near‐infrared (NIR) visualization may assist in selection of intestinal transection level and subsequent anastomotic vascular sufficiency. This study examined the use of NIR‐ICG imaging in colorectal surgery.

Methods

This was a prospective phase II study (NCT02459405) of non‐selected patients undergoing any elective colorectal operation with anastomosis over a 3‐year interval in three tertiary hospitals. A standard protocol was followed to assess NIR‐ICG perfusion before and after anastomosis construction in comparison with standard operator visual assessment alone.

Results

Five hundred and four patients (median age 64 years, 279 men) having surgery for neoplastic (330) and benign (174) pathology were studied. Some 425 operations (85·3 per cent) were started laparoscopically, with a conversion rate of 5·9 per cent. In all, 220 patients (43·7 per cent) underwent high anterior resection or reversal of Hartmann's operation, and 90 (17·9 per cent) low anterior resection. ICG angiography was achieved in every patient, with a median interval of 29 s to visualization of the signal after injection. NIR‐ICG assessment resulted in a change in the site of bowel division in 29 patients (5·8 per cent) with no subsequent leaks in these patients. Leak rates were 2·4 per cent overall (12 of 504), 2·6 per cent for colorectal anastomoses and 3 per cent for low anterior resection. When NIR‐ICG imaging was used, the anastomotic leak rates were lower than those in the participating centres from over 1000 similar operations performed with identical technique but without NIR‐ICG technology.

Conclusion

Routine NIR‐ICG assessment in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery is feasible. NIR‐ICG use may change intraoperative decisions, which may lead to a reduction in anastomotic leak rates.

Short abstract

Appears to reduce leaks

Introduction

Colorectal surgery frequently involves bowel resection with restoration of alimentary continuity by anastomosis. Anastomotic breakdown is one of the most feared complications owing to the associated clinical and economic consequences1. Leakage is more common in distally positioned anastomoses2. Reported anastomotic leak rates vary. Large national audits3, 4 have reported anastomotic leak rates of between 2·8 and 4 per cent after colorectal surgery. The recent European Society of Coloproctology snapshot audit5 of 3208 right hemicolectomies reported an anastomotic complication rate of 8·1 per cent. In Denmark, a country with high levels of centralization, leak rates were 4·8 per cent after right colectomy, 5·8 per cent after high anterior resection (HAR) and 10·8 per cent after low anterior resection (LAR)6.

Among many risk factors, only some can be addressed by preoperative optimization2, 7. Although avoidance of anastomotic tension during surgery and perfusion insufficiency at the time of anastomosis is believed to be beneficial, their exact interpretation is subjective. Many attempts have been made to assess perianastomotic vascularization objectively, but most methods are difficult to implement routinely and so have not been adopted broadly8. Most recently, near‐infrared (NIR) laparoscopy has emerged as a simple, reproducible technique for real‐time assessment of intestinal microvascularization using indocyanine green (ICG) angiography9. It may be associated with a reduced rate of anastomotic complications10, 11, 12. The PILLAR (Perfusion Assessment in Laparoscopic Left‐Sided/Anterior Resection) II study13 reported a leak rate of 1·9 per cent among 139 left‐sided colorectal resections for predominantly benign disease, and others have shown similar improvements in smaller series14, 15, 16.

This multicentre prospective phase II study measured leak rates in elective laparoscopic and open colorectal surgery using endoscopic NIR‐ICG technology, and compared leak rates with historical data from the same surgeons performing similar surgery without NIR‐ICG.

Methods

This multicentre prospective open‐label clinical study was performed between January 2013 and December 2016. Participating institutions were Geneva University Hospitals, Switzerland, Mater Misericordiae University Hospital, Ireland, and Oxford University Hospitals, UK.

Patient selection

Approval for the study was granted at all centres after departmental, institutional and external peer approval of the protocol and associated documentation. This included a successful application to an independent research ethics committee (ethics committee approval number: 10/H0724/13; clinical trial reference number: NCT02459405). All patients aged over 18 years scheduled for elective colorectal surgery involving resection and anastomosis of any type were considered for inclusion; there were no other selection criteria. All eligible patients were recruited prospectively at each site and fully consented before participation. All were informed that inclusion was voluntary and additional to routine care. Exclusion criteria were: failure to meet the inclusion criteria; pregnancy or lactation; previous adverse reaction or allergy to ICG or iodine; significant liver dysfunction; emergency surgery; refusal to participate after informed consent was sought; and lack of availability of the NIR‐ICG laparoscope owing to recent use/need for sterilization. The study interval of 3 years was based on practical considerations to ensure a cohort of substantial size and clinical case‐match representation to diminish bias resulting from limited availability of equipment at the study centres or individual surgeon practice.

Indocyanine green–near‐infrared technique

ICG use for intraoperative perfusion angiography has been described previously17, 18. In brief, ICG absorbs light in the NIR range between 790 and 805 nm, and re‐emits electromagnetic energy at 835 nm, which can be visualized by its fluorescence in the vasculature by NIR irradiation. Circulatory half‐life is 3–5 min and the rate of allergic reaction is one per 333 000. Some 7·5 mg ICG Pulsion® (Pulsion Medical Systems, Munich, Germany; cost approximately €50 per 25‐mg vial) was used at a concentration of 2·5 mg/ml (3 ml per injection). It was supplied as a sterile lyophilized powder and reconstituted in water.

A PINPOINT® Endoscopic Fluorescence Imaging System (Stryker, Kalamazoo, Michigan, USA) was used at each centre. This system provides high‐definition white and NIR laparoscopic light and rapid image sequencing, creating a superimposition of NIR upon standard white‐light views using false green signal colouring to allow an enhanced real‐time view of perfusion.

NIR‐ICG assessment was compared with standard intraoperative visualization at two critical intraoperative time points, just before and after construction of the anastomosis. Surgery was performed by the standard technique of the senior operating surgeon up until the point of proximal colonic division (after full specimen mobilization and main vessel ligation). After the surgeon had decided on the proximal site of division, an intravenous bolus of ICG was administered, and the first acquisition image was attained under NIR by switch activation of the PINPOINT® camera while the fluorescence angiogram developed. Time to view the microvascularization and haemodynamics at this time were recorded, along with the intestinal appearances of the proximal bowel in comparison with non‐mobilized bowel segments. Where possible, the distal intestinal segments were viewed in a similar manner. Any deviation or change in transection point was recorded. The anastomosis was constructed by the surgeon's usual technique. Thereafter, the second acquisition for NIR‐ICG evaluation was performed and the appearances recorded either serosally or intraluminally. Any decision to redo the anastomosis was recorded, along with haemodynamic details. The decision to defunction the anastomosis was made according to usual local practice.

Elective colorectal resections were categorized by route of access and by procedure, as follows: right hemicolectomy, which included ileocaecal resection, right hemicolectomy and extended right hemicolectomy; HAR, defined as left‐sided colonic resection with anastomosis above or at the level of the peritoneal reflection; and LAR, defined as a left‐sided colorectal resection with anastomosis below the level of the peritoneal reflection, including ultralow (anastomosis within 5 cm of the anal verge) and coloanal anastomosis. Ileoanal pouch procedures, operations in which an ileorectal anastomosis was performed and reversal of Hartmann's procedures were recorded separately. An ‘others’ group comprised jejeunal or ileal operations with small bowel anastomosis. No loop stoma closures were included.

Routine perioperative care at all centres included use of an enhanced recovery programme. Antegrade bowel preparation was used selectively, predominantly for LAR with a planned defunctioning stoma, as were purgative enemas (usually for other left‐sided resections). Oral antibiotics were not used.

Data collection

Patient characteristics, intraoperative parameters (operative access, duration of surgery, conversion rate and rationale, flexure mobilization, level of vessel ligation, number of stapler firings, ostomy, drain use) and postoperative outcomes were collected prospectively. Duration of the ICG procedure (interval between injection of ICG and the end of signal acquisition), any adverse reaction, fluorescence signal quality and total duration of surgery were recorded as well as any change in procedure. Heart rate, BP and oxygen saturation were also recorded, including use of any pharmacological adjuvants. Postoperative complications were graded according to the Clavien–Dindo classification19, 20. An anastomotic leak was defined as a ‘communication between the intra‐ and extra‐luminal compartment owing to a defect of the integrity of the intestinal wall at the anastomotic site’21, and was recorded when detected clinically. Data on cohort outcomes and complications for comparison were taken from previous published experiences from the centres22, audit databases or Hospital Inpatient Enquiry data from the period immediately before the start of the present study, or from contemporaneous patients whose surgery did not include use of NIR‐ICG imaging.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are expressed as median (range). Continuous variables were analysed using the χ2 test. All tests were carried out using the standard α level of 0·05 to indicate statistical significance.

Results

The use of NIR‐ICG technology was studied in 504 patients undergoing elective bowel resection. Overall patient demographics along with indications for operation and procedures are shown in Table 1. Colorectal cancer was the indication for surgery in 330 patients, including all those who had LAR. Laparoscopy was the mode of access in 425 procedures (85·3 per cent) with a conversion rate of 5·9 per cent. Ninety patients underwent LAR; in 84 (93 per cent) the operation was commenced laparoscopically (conversion rate 8 per cent), and 85 (94 per cent) had a defunctioning ileostomy. Among the 310 patients having left‐sided colorectal anastomoses (HAR, LAR and Hartmann's reversal), 295 (95·2 per cent) had full splenic flexure mobilization.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and operative category by procedure type and access

| No. of patients* (n = 504) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years)† | 64 (18–88) |

| Sex ratio (M : F) | 279 : 225 |

| BMI (kg/m2)† | 25 (13–57) |

| ASA fitness grade | |

| I | 71 (14·1) |

| II | 343 (68·1) |

| III | 89 (17·7) |

| IV | 1 (0·2) |

| Indication for surgery | |

| Colorectal cancer | 330 (65·5) |

| Diverticular disease | 95 (18·8) |

| Crohn's disease | 43 (8·5) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 15 (3·0) |

| Other | 21 (4·2) |

| Operative procedure | |

| Right hemicolectomy | 143 (28·4) |

| High anterior resection | 191 (37·9) |

| Low anterior resection | 90 (17·9) |

| Reversal of end colostomy (Hartmann's operation) | 29 (5·8) |

| Ileoanal J pouch | 12 (2·4) |

| Ileorectal anastomosis | 11 (2·2) |

| Other | 28 (5·6) |

| Surgical approach | |

| Laparoscopy | 425 (84·3) |

| Open surgery | 79 (15·7) |

| Conversion to open surgery | 25 of 425 (5·9) |

With percentages in parentheses unless indicated otherwise;

values are median (range).

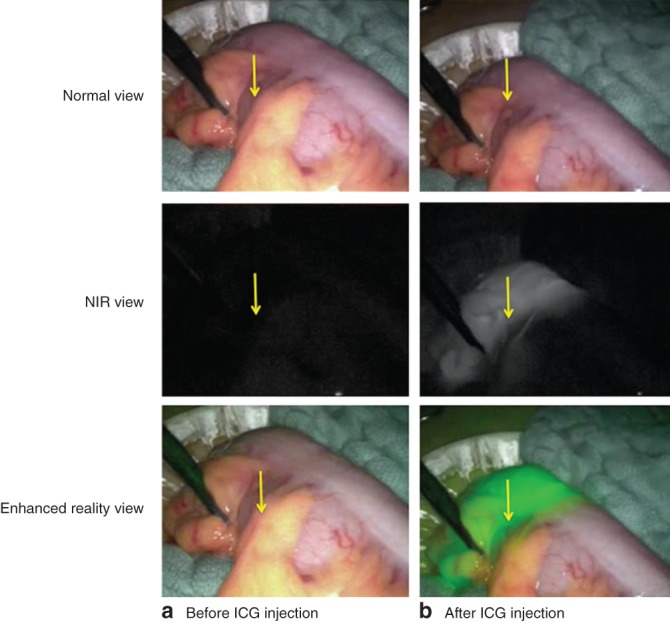

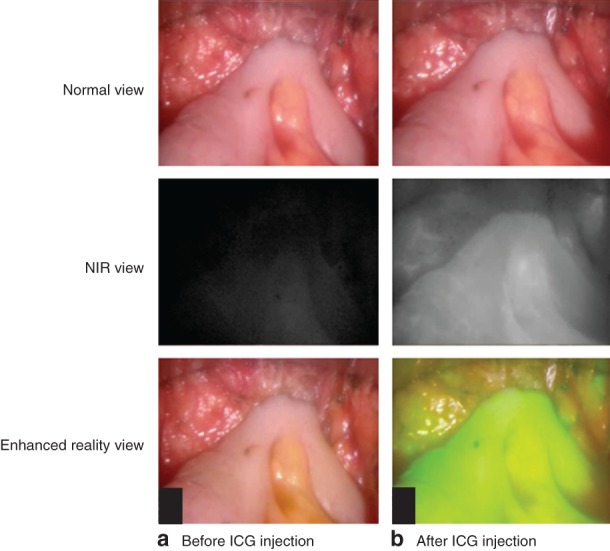

Intraoperative NIR‐ICG perfusion data are summarized in Table 2. An intraoperative NIR‐ICG angiogram with a clear distinction between the vascularized and devascularized areas was achieved in all patients (Fig. 1; Video S1, supporting information). The distal rectal stump was viewable in every LAR. The median time to visualization of ICG fluorescence was 29 s, with no significant difference by intestinal site. The median additional operating time to assess bowel perfusion was 4 min per NIR‐ICG acquisition. Although there was some persistent fluorescence signal at the second acquisition time point in every patient, an augmented fluorescence signal could always readily be appreciated after the second ICG dose (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Performance characteristics of near‐infrared indocyanine green perfusion assessment and subsequent change in planned anastomotic site

| No. of patients* (n = 504) | |

|---|---|

| Failure to acquire NIR image | 0 (0) |

| Duration of each NIR image acquisition (min)† | 4 (1–20) |

| Time to visualization of ICG fluorescence in the anastomosis (s)† | 29 (10–158) |

| Quality of ICG perfusion before anastomosis | |

| Satisfactory | 481 (95·5) |

| Unsatisfactory (revision of decision to proceed) | 23 (4·5) |

| Quality of ICG perfusion after anastomosis | |

| Satisfactory | 503 (99·8) |

| Avoidance of proximal defunctioning ileostomy in patients undergoing LAR | 5 of 90 (6) |

| Unsatisfactory, leading to change of plan (redo anastomosis) | 1 (0·2) |

| Global intraoperative change of plan owing to NIR‐ICG finding | 29 (5·8) |

| Leak rate in patients in whom NIR‐ICG led to change of plan | 0 of 29 |

With percentages in parentheses unless indicated otherwise;

values are median (range). NIR, near‐infrared; ICG, indocyanine green; LAR, low anterior resection.

Figure 1.

Near‐infrared (NIR) assessment of level of transection. Images of a planned transection before indocyanine green (ICG) injection (arrow) and b visible transection area after ICG injection (arrow) are shown in normal view, NIR view and enhanced reality view. There is no change in transection area if the perfusion signal reaches the planned area for transection

Figure 2.

Near‐infrared (NIR) perfusion assessment after a side‐to‐end colorectal anastomosis had been constructed. Intraoperative images of the anastomosis a before and b after indocyanine green (ICG) injection are shown in normal view, NIR view and enhanced reality view. After ICG injection, there was a good signal on the rectal stump and colon

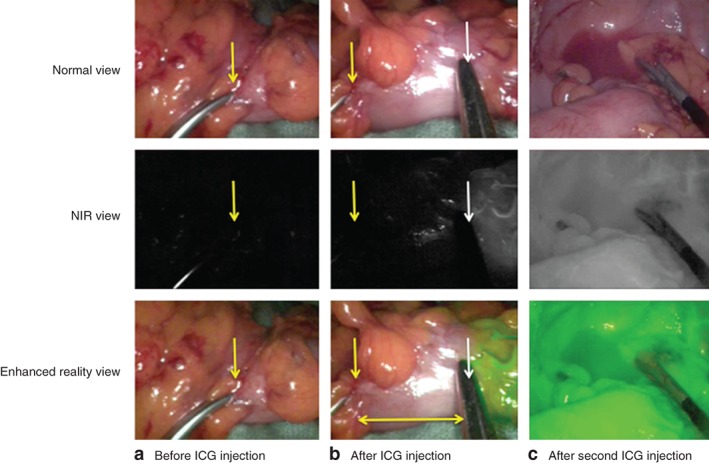

The NIR appearance led to a change in the procedure compared with that intended from routine assessment alone in 29 patients (5·8 per cent of patients overall). Most variance was at the time of first acquisition (23 of 29, 79 per cent) and all related to the proximal bowel appearance rather than the rectal stump (when viewable). The length of proximal shift ranged from 0·5 to 20 cm (Fig. 3; Video S2, supporting information). One patient was found to have insufficient anastomotic perfusion on the second acquisition and the anastomosis was redone. In five patients undergoing LAR, who would usually have had a covering defunctioning stoma in accordance with local protocol, the NIR‐ICG appearance encouraged the surgeon to forgo the ileostomy. None developed anastomotic leakage.

Figure 3.

Near‐infrared (NIR) perfusion assessment with change of plan owing to a lack of perfusion at the level of the section originally planned. Intraoperative images are shown in normal view, NIR view and enhanced reality view. a Image before indocyanine green (ICG) injection showing the planned area for proximal transection (yellow arrow) in a segment of descending colon after its mobilization (including high vascular ligation) and mesocolic preparation. b After ICG injection, a clear demarcation line appeared (white arrow) that was 4 cm more proximal (vertical yellow arrow on the initial transection area) and led to more proximal transection (horizontal arrow shows distance that has been assessed as well perfused) being undertaken. c A second injection of ICG in the same patient showed satisfactory perfusion of the constructed colorectal anastomosis in situ

Median hospital stay was 7 (range 2–95) days. There was no postoperative death. Postoperative morbidity was recorded in 177 patients (35·1 per cent), comprising a total of 229 complications. According to the Clavien–Dindo classification, 134 complications (58·5 per cent of 230) were grade I, 68 (29·7 per cent) grade II, nine (3·9 per cent) grade IIIa and 18 (7·9 per cent) grade IIIb. Twenty patients (4·3 per cent) needed a reoperation.

Twelve patients (2·4 per cent) had an anastomotic leak. There were four leaks following right hemicolectomy (2·8 per cent of 143) and each required reoperation. Five of 220 patients (2·3 per cent) with high colorectal anastomoses (either HAR or reversal of Hartmann's operation) developed anastomotic leaks, all of whom underwent reoperation. The site of leakage was within the anastomosis in four patients, and to the side of a side‐to‐end anastomosis in one. All these anastomoses were taken down with subsequent end colostomy formation. Three leaks occurred in those undergoing LAR (3 per cent), in one patient after a staple misfire and suturing of the anastomosis during the index procedure. Each of these three leaks was treated with transanal or percutaneous drainage, allowing salvage of the anastomosis. There were no leaks among patients undergoing either J‐pouch or ileorectal anastomosis. None of the patients in whom the NIR‐ICG assessment indicated a change in procedure developed a postoperative leak. Intraoperative use of vasoactive drugs or BP values (systolic or diastolic) had no significant association with postoperative leakage.

The leak rates observed in the present cohort were compared with data collated from 1173 patients having similar surgery in the same study centres before or during the study period, but without use of NIR‐ICG technology. The overall leak rate for colorectal operations not involving ICG‐NIR was 5·8 per cent (68 of 1173), compared with 2·6 per cent (12 of 453) with use of NIR‐ICG imaging in the present study (P = 0·009). For right‐sided operations, the leak rates were 2·6 per cent (8 of 302) and 2·8 per cent (4 of 143) respectively (P = 0·928). For left‐sided operations, rates were 6·9 per cent (60 of 871) versus 2·6 per cent (8 of 310) (P = 0·005). Excluding reversal of Hartmann's operations from these figures, the leak rates for left‐sided operations including both disease resection and anastomosis were 6·8 per cent (60 of 871) versus 2·5 per cent (7 of 281) (P = 0·006). For LARs alone, the leak rates were 10·7 per cent (39 of 365) versus 3 per cent (3 of 90) (P = 0·031).

Discussion

This prospective multicentre phase II study showed that NIR‐ICG technology can be used to assess intestinal vascularity before and after anastomosis, without greatly increasing operating time when no change is made to the proposed anastomotic site. Unlike previous studies, the present experience includes patients, procedures, surgical access and anastomotic levels not extensively studied previously using NIR‐ICG technology. The leak rates and frequency of change in intraoperative plan are consistent with those in the PILLAR II trial13.

The anastomotic leak rates in this study using NIR‐ICG imaging were lower than rates from the participating centres based on over 1000 similar operations performed with identical techniques, but without use of NIR‐ICG. However, the considerable heterogeneity and inherent bias related to case mix between these groups make accurate interpretation of comparative data difficult (and inappropriate for formal inclusion in a phase II study). Nevertheless, there was a significant decrease in leak rate overall (5·8 per cent without imaging compared with 2·6 per cent in the present series for colorectal procedures), among those undergoing left‐sided resection and, most strikingly, in LAR (10·7 versus 3 per cent). If the anastomosis had leaked in all patients in whom NIR‐ICG assessment led to a revision in the section of bowel, the anastomotic complication rates would have been similar to historical levels. Taken together, these findings suggest that routine NIR‐ICG imaging is useful. A phase III, randomized study is now planned to prove the effectiveness of NIR‐ICG imaging (IntAct: Intraoperative Fluorescence Angiography to Prevent Anastomotic Leak in Rectal Cancer Surgery study23).

In the present study, NIR‐ICG technology was used to assess bowel vascularity during inflammatory bowel disease surgery, including patients undergoing ileoanal J‐pouch anastomosis. J‐pouch vascularization assessment may be especially important in procedures involving manoeuvres to elongate the mesentery that may jeopardize pouch vascularity. Another potential benefit of NIR‐ICG imaging may be to reduce the need for a covering stoma above a low anastomosis.

Unfortunately, anastomotic leaks were not abolished by use of NIR‐ICG imaging and the technology did not seem to add any value to ileocolic anastomoses. This likely reflects the multifactorial nature of non‐healing anastomoses, and indicates that other site‐ and patient‐specific factors remain important24. Vascularization at the time of anastomosis construction is also not necessarily a guarantee of postoperative maintenance of perfusion sufficiency.

Healthcare costs are of major concern worldwide. New technologies must therefore be cost‐effective before widespread adoption. Aside from the personal misery, morbidity and mortality associated with an anastomotic leak, recent economic evaluations suggest that it increases the cost of the index hospital admission by between €11 90025 and €20 30026. Such data may vary considerably by jurisdiction, patient and centre, and also do not account for all consequential healthcare costs, including those for later reoperation to restore gastrointestinal continuity, stoma care, and loss of productivity. The 5‐year cost associated with the purchase and maintenance of the endoscopic system used in this experience is approximately €110 000, whereas the cost of ICG and mean added theatre time used for three acquisitions is approximately €130 per patient. The acquisition of a NIR‐ICG system could therefore be justified and the costs covered in a year, if it can be proven definitively to prevent two anastomotic leaks per year.

The potential benefit of this technology is unlikely to be confined to any specific system or manufacturer. One of the main drawbacks of present iterations of all available NIR‐ICG laparoscopes is their absence of signal quantification. Although the images show clear transition zones, they do not indicate relative adjacent regional perfusion (preclinical work suggests that 30–50 per cent of normal perfusion permits anastomotic healing). Although each operator in this series used a visual positive control, better standardization in signal interpretation, including defined indicative thresholds and their optimal display, would enable cross‐platform standardization. Maximum intensity signal kinetic analysis could also reveal non‐arterial perfusion effects (such as venous return). Automated analytical software is in development for the purpose of more precise objective quantification, and is being investigated for incorporation into clinical use alongside NIR‐ICG imaging27, 28. ICG is non‐selective and thus allows only crude assessment of vascularization. Targeted fluorophores activated by specific cells or microenvironments (perhaps local tissue pH, hypoxia, lactate or other metabolites) are in near‐term development29, and could also allow more precise tissue interrogation30.

The main limitations of this study are that it is not randomized and that it lacks a prospective case‐matched control group, and so does not provide definitive proof of benefit. The results of this experience do, however, confirm and build on earlier findings that NIR assessment of anastomotic microperfusion using ICG may help surgeons improve the quality of surgery.

Editor's comments

Supporting information

Video S1.

Video S2.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contribution of the scrub nurse team at each institution, and the fellows and registrars at each centre who helped with patient and procedural care. They also acknowledge the support of the Oxford Colon Cancer Trust (OCCTOPUS) and the New Surgical Technology Foundation (FNTC), Switzerland. PINPOINT® endoscopic systems were provided under an unrestricted use agreement from Novadaq Corporation. No right of review of the data or manuscript was requested or provided, and no industry funding was provided for the performance of this trial.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Presented to the Annual Meeting of the European Society of Coloproctology, Milan, Italy, September 2016, and to a meeting of the Swiss Surgical Society, Berne, Switzerland, May 2017; published in abstract form as Colorectal Dis 18(Suppl 1): 7 and Br J Surg 2017; 104(Suppl S4): 11

References

- 1. Vallance A, Wexner S, Berho M, Cahill R, Coleman M, Haboubi N et al A collaborative review of the current concepts and challenges of anastomotic leaks in colorectal surgery. Colorectal Dis 2017; 19: O1–O12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pommergaard HC, Gessler B, Burcharth J, Angenete E, Haglind E, Rosenberg J. Preoperative risk factors for anastomotic leakage after resection for colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Colorectal Dis 2014; 16: 662–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Scarborough JE, Mantyh CR, Sun Z, Migaly J. Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation reduces incisional surgical site infection and anastomotic leak rates after elective colorectal resection: an analysis of colectomy‐targeted ACS NSQIP. Ann Surg 2015; 262: 331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sammour T, Hayes IP, Jones IT, Steel MC, Faragher I, Gibbs P. Impact of anastomotic leak on recurrence and survival after colorectal cancer surgery: a BioGrid Australia analysis. ANZ J Surg 2018; 88: E6–E10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. 2015 European Society of Coloproctology Collaborating Group . The relationship between method of anastomosis and anastomotic failure after right hemicolectomy and ileo‐caecal resection: an international snapshot audit. Colorectal Dis 2017; 19: e296–e311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jessen M, Nerstrøm M, Wilbek TE, Roepstorff S, Rasmussen MS, Krarup PM. Risk factors for clinical anastomotic leakage after right hemicolectomy. Int J Colorectal Dis 2016; 31: 1619–1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McDermott FD, Heeney A, Kelly ME, Steele RJ, Carlson GL, Winter DC. Systematic review of preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative risk factors for colorectal anastomotic leaks. Br J Surg 2015; 102: 462–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ris F, Yeung T, Hompes R, Mortensen NJ. Enhanced reality and intraoperative imaging in colorectal surgery. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2015; 28: 158–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chadi SA, Fingerhut A, Berho M, DeMeester SR, Fleshman JW, Hyman NH et al Emerging trends in the etiology, prevention, and treatment of gastrointestinal anastomotic leakage. J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 20: 2035–2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sherwinter DA. Transanal near‐infrared imaging of colorectal anastomotic perfusion. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2012; 22: 433–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sherwinter DA, Gallagher J, Donkar T. Intra‐operative transanal near infrared imaging of colorectal anastomotic perfusion: a feasibility study. Colorectal Dis 2013; 15: 91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ris F, Hompes R, Cunningham C, Lindsey I, Guy R, Jones O et al Near‐infrared (NIR) perfusion angiography in minimally invasive colorectal surgery. Surg Endosc 2014; 28: 2221–2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jafari MD, Wexner SD, Martz JE, McLemore EC, Margolin DA, Sherwinter DA et al Perfusion assessment in laparoscopic left‐sided/anterior resection (PILLAR II): a multi‐institutional study. J Am Coll Surg 2015; 220: 82–92.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Boni L, David G, Dionigi G, Rausei S, Cassinotti E, Fingerhut A. Indocyanine green‐enhanced fluorescence to assess bowel perfusion during laparoscopic colorectal resection. Surg Endosc 2016; 30: 2736–2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boni L, Fingerhut A, Marzorati A, Rausei S, Dionigi G, Cassinotti E. Indocyanine green fluorescence angiography during laparoscopic low anterior resection: results of a case‐matched study. Surg Endosc 2017; 31: 1836–1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jafari MD, Lee KH, Halabi WJ, Mills SD, Carmichael JC, Stamos MJ et al The use of indocyanine green fluorescence to assess anastomotic perfusion during robotic assisted laparoscopic rectal surgery. Surg Endosc 2013; 27: 3003–3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cahill RA, Ris F, Mortensen NJ. Near‐infrared laparoscopy for real‐time intra‐operative arterial and lymphatic perfusion imaging. Colorectal Dis 2011; 13(Suppl 7): 12–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ris F, Hompes R, Lindsey I, Cunningham C, Mortensen NJ, Cahill RA. Near infra‐red laparoscopic assessment of the adequacy of blood perfusion of intestinal anastomosis – a video vignette. Colorectal Dis 2014; 16: 646–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD et al The Clavien–Dindo classification of surgical complications: five‐year experience. Ann Surg 2009; 250: 187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004; 240: 205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rahbari NN, Weitz J, Hohenberger W, Heald RJ, Moran B, Ulrich A et al Definition and grading of anastomotic leakage following anterior resection of the rectum: a proposal by the International Study Group of Rectal Cancer. Surgery 2010; 147: 339–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Buchs NC, Gervaz P, Secic M, Bucher P, Mugnier‐Konrad B, Morel P. Incidence, consequences, and risk factors for anastomotic dehiscence after colorectal surgery: a prospective monocentric study. Int J Colorectal Dis 2008; 23: 265–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. ISRCTN Registry . IntAct: Intraoperative Fluorescence Angiography to Prevent Anastomotic Leak in Rectal Cancer Surgery https://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN13334746?q=intact-ifa&filters=&sort=&offset=1&totalResults=1&page=1&pageSize=10&searchType=basic-search [accessed 3 September 2017].

- 24. Shogan BD, Belogortseva N, Luong PM, Zaborin A, Lax S, Bethel C et al Collagen degradation and MMP9 activation by Enterococcus faecalis contribute to intestinal anastomotic leak. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7: 286ra68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ashraf SQ, Burns EM, Jani A, Altman S, Young JD, Cunningham C et al The economic impact of anastomotic leakage after anterior resections in English NHS hospitals: are we adequately remunerating them? Colorectal Dis 2013; 15: e190–e198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hammond J, Lim S, Wan Y, Gao X, Patkar A. The burden of gastrointestinal anastomotic leaks: an evaluation of clinical and economic outcomes. J Gastrointest Surg 2014; 18: 1176–1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Diana M, Noll E, Diemunsch P, Dallemagne B, Benahmed MA, Agnus V et al Enhanced‐reality video fluorescence: a real‐time assessment of intestinal viability. Ann Surg 2014; 259: 700–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Diana M, Agnus V, Halvax P, Liu YY, Dallemagne B, Schlagowski AI et al Intraoperative fluorescence‐based enhanced reality laparoscopic real‐time imaging to assess bowel perfusion at the anastomotic site in an experimental model. Br J Surg 2015; 102: e169–e176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Daly HC, Sampedro G, Bon C, Wu D, Ismail G, Cahill RA et al BF2‐azadipyrromethene NIR‐emissive fluorophores with research and clinical potential. Eur J Med Chem 2017; 135: 392–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nguyen QT, Tsien RY. Fluorescence‐guided surgery with live molecular navigation‐‐a new cutting edge. Nat Rev Cancer 2013; 13: 653–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video S1.

Video S2.