Abstract

Objective:

Integrated or collaborative care is a well-evidenced and widely practiced approach to improve access to high-quality mental health care in primary care and other settings. Psychiatrists require preparation for this emerging type of practice, and such training is now mandatory for Canadian psychiatry residents. However, it is not known how best to mount such training, and in the absence of such knowledge, the quality of training across Canada has suffered. To guide integrated care education nationally, we conducted a systematic review of published and unpublished training programs.

Method:

We searched journal databases and web-based ‘grey’ literature and contacted all North American psychiatry residency programs known to provide integrated care training. We included educational interventions targeting practicing psychiatrists or psychiatry residents as learners. We critically appraised literature using the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI). We described the goals, content, and format of training, as well as outcomes categorized according to Kirkpatrick level of impact.

Results:

We included 9 published and 5 unpublished educational interventions. Studies were of low to moderate quality and reflected possible publication bias toward favourable outcomes. Programs commonly involved longitudinal clinical experiences for residents, mentoring networks for practicing physicians, or brief didactic experiences and were rarely oriented toward the most empirically supported models of integrated care. Implementation challenges were widespread.

Conclusions:

Similar to integrated care clinical interventions, integrated care training is important yet difficult to achieve. Educational initiatives could benefit from faculty development, quality improvement to synergistically improve care and training, and stronger evaluation.

Systematic review registration number:

PROSPERO 2014:CRD42014010295.

Keywords: collaborative care, shared care, integrated care, mental health, psychiatry, primary care, family medicine, interprofessional relations, graduate medical education, continuing medical education

Abstract

Objectif:

Les soins intégrés ou collaboratifs constituent une approche fondée sur de solides données probantes et largement pratiquée pour améliorer l’accès à des soins de santé mentale de grande qualité dans les soins de première ligne et d’autres contextes. Les psychiatres nécessitent une préparation à ce nouveau type de pratique, et cette formation est désormais obligatoire pour les résidents en psychiatrie canadiens. Cependant, on ne connaît pas encore la meilleure manière d’organiser cette formation, et à défaut de cette connaissance, la formation pancanadienne a souffert. Afin de guider l’éducation en soins intégrés à l’échelle nationale, nous avons mené une revue systématique des programmes de formation publiés et inédits.

Méthode:

Nous avons cherché les bases de données des publications et la littérature « grise » sur le Web, et communiqué avec tous les programmes nord-américains de résidence en psychiatrie qui offrent la formation en soins intégrés. Nous avons inclus les interventions éducatives ciblant les psychiatres actifs ou les résidents en psychiatrie comme apprenants. Nous avons fait une évaluation critique de la littérature à l’aide de l’instrument de qualité de l’étude de recherche en formation médicale (MERSQI). Nous avons décrit les buts, le contenu et le format de la formation, ainsi que les résultats catégorisés selon le niveau d’impact de Kirkpatrick.

Résultats:

Nous avons inclus 9 interventions éducatives publiées et 5 inédites. Les études étaient de qualité faible à modérée et reflétaient un biais de publication possible à l’égard de résultats favorables. Les programmes comportaient communément des expériences cliniques longitudinales pour les résidents, des réseaux de mentorat pour les psychiatres actifs, ou de brèves expériences didactiques, et étaient rarement orientés vers les modèles de soins intégrés les mieux soutenus empiriquement. Les problèmes de mise en œuvre étaient répandus.

Conclusions:

À l’instar des interventions cliniques de soins intégrés, la formation en soins intégrés est importante mais difficile à réaliser. Les initiatives éducatives pourraient profiter du développement du corps professoral, de l’amélioration de la qualité afin d’améliorer de façon synergique les soins et la formation, et d’une évaluation plus forte.

Integrated mental health care models improve access to high-quality mental health care outside of specialized settings and address the high burden of mental illness.1,2 Known as collaborative, shared, or integrated mental health care (henceforward ‘integrated care’), these approaches involve psychiatrists, primary care providers (PCPs), and other health care professionals working together to improve outcomes for a defined population.2,3 There is a spectrum of integration from colocation or consultation-liaison of mental health specialists in a primary care setting (physically or virtually via telepsychiatry) to chronic care models that include support for patient self-management, measurement-based care, clinical registries enabling proactive outreach, and decision support to guide steps in care targeting remission.4 These innovations in care delivery have well-demonstrated efficacy in improving timeliness of care, clinical outcomes, and cost effectiveness of care, with the most empirical support for the chronic care model.2,5–8

However, transferring and scaling up integrated care from clinical trials to ‘real-world’ settings has proven challenging.9,10 One significant barrier is the need for health care providers to be trained in new ways of working with patients and clinical teams and using individual and population data to inform care.2,11–16 Although large-scale efforts to train psychiatrists are now under way across North America, including mandatory training for all Canadian psychiatry residents, it is not known how best to prepare psychiatrists to work in these evolving models of mental health service delivery.17,18 This knowledge gap has had significant consequences for the variability and overall quality of existing training across the country.19 Kates’s chapter in Approaches to Postgraduate Education in Psychiatry in Canada has provided a useful starting point during the first few years of mandatory training across Canada by suggesting learning objectives and educational strategies20; however, to advance the field, an empirical approach is also needed.

We conducted a systematic review of the literature in which we aimed to identify all integrated care training experiences that have been evaluated in published and unpublished sources; examine their goals, contents, methods and outcomes; and distill, where possible, evidence-informed recommendations for psychiatric training.

Methods

The primary objective of this systematic review was to synthesize and critically appraise training curricula and methods that have been used to develop psychiatrists’ competence for the practice of integrated care. The study objectives were outlined a priori in a published protocol.21 We developed the following eligibility criteria based on our knowledge of the field as integrated care providers, educators, and researchers.

Population

We selected interventions that targeted junior and senior psychiatric residents, fellows, faculty members, and practicing psychiatrists. We excluded undergraduate medical trainees who are undifferentiated as learners working across many disciplines. We excluded training initiatives targeted exclusively toward other health care providers.

Intervention

We included any educational intervention that trained the study population in integrated care and included an evaluative component. To be considered integrated care, the focus of training had to meet 3 parameters of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality typology, including a) an interprofessional team, b) working with some degree of collaboration (e.g., co-located, coordinated, consultation-liaison, or chronic care models) in person or at a distance (e.g., telepsychiatry), and c) with a shared population and mission.22

Comparator

We included studies regardless of the presence or absence of a comparison group in the evaluation.

Outcomes

We examined all psychiatric learner, co-learner, and patient outcomes at all Kirkpatrick levels.23 The Kirkpatrick model outlines 4 levels of educational impact, including 1) reaction/satisfaction: learner views on the learning experience, its organization, content, teaching methods, materials, and quality; 2) learning: changes in perceptions and attitudes (including plans for future practice) and acquisition of knowledge and skills, including problem solving and social skills; 3) behaviour: changes in workplace performance; and 4) results: organizational and clinical outcomes.

Literature Search

We conducted an extensive literature search of English-language published and unpublished literature to August 2015 that included all quantitative and qualitative study designs and time periods (see supplemental file for details). We also reached out to directors of psychiatry residency programs in North America who were known to include integrated care in the curriculum, inquiring about both residency training and faculty development. In Canada, integrated care training is mandatory for psychiatry residents, so we contacted all programs via the Council of Psychiatric Educators. For the United States, we relied upon the American Association of Directors of Psychiatry Residency Training (AADPRT) database.

Abstract and Full-Text Screening

Two research team members independently reviewed all titles and abstracts using DistillerSR software to determine inclusion, resolving any differences of opinion by consensus discussion between team members and the study lead. Then, at least 2 researchers conducted a full-text review in a similar fashion. We assessed interobserver agreement for inclusion of studies using a chance-corrected kappa statistic.

Data Collection and Critical Appraisal

Two research team members abstracted data for each included citation. We collected quantitative and qualitative information related to the learners, educational intervention, and methods and results of evaluation. For unpublished programs, we collected the same data by e-mail and/or telephone. We assessed study quality using the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI), which is a 10-item tool that appraises study design, sampling, type of data, validity, data analysis, and outcomes.24 Each of the 6 domains can produce a maximum score of 3, resulting in a maximum possible MERSQI score of 18. We used the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) or the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale-Education (NOS-E) as supplemental tools to assess the risk of bias of qualitative and observational studies, respectively, if applicable.24,25

Data Analysis

We prepared descriptive statistics of the learners, evaluation design, and outcomes measured. We extracted descriptions of each educational intervention: program goals, curriculum content and/or clinical workplace activities, supervision provided, and program duration. For each outcome measured, we prepared a brief description and assessed the Kirkpatrick level and strength to draw conclusions about the intervention.23,26,27 We summarized a list of unique outcomes evaluated in this body of literature and also described broad themes. The data were predominantly textual; therefore, we employed qualitative content analysis techniques.28 We inductively developed categories or ‘codes’ describing outcomes of training as they emerged from our close reading and immersion in the data; then we refined, sorted, and grouped these codes based on their relationships to each other; and finally, we interpreted the data using written summaries and tables.29,30

Results

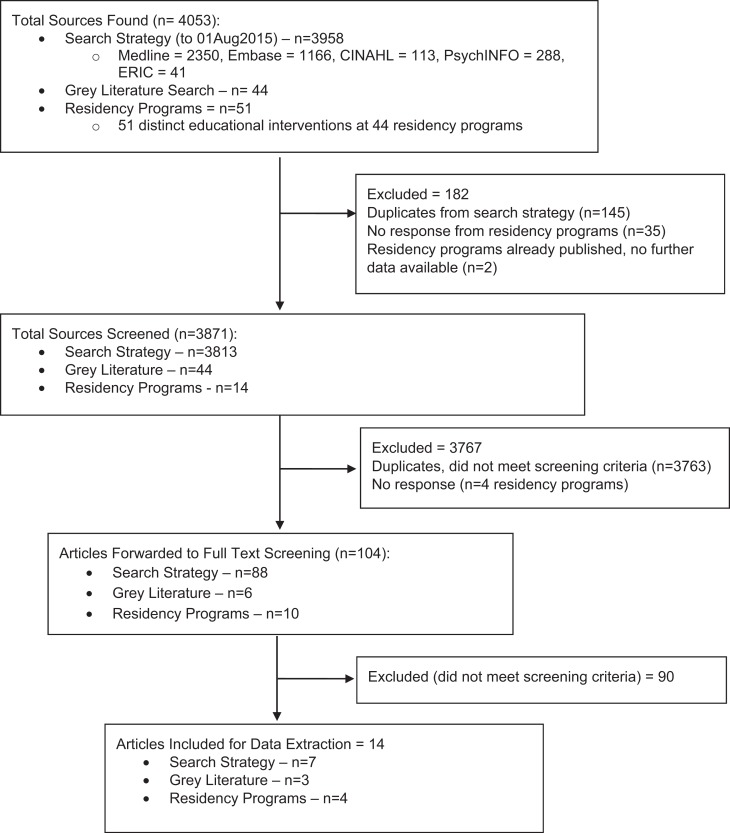

We screened 3871 educational interventions, including 3813 published literature citations, 44 grey literature documents, and 14 residency programs (see Figure 1 for PRISMA diagram). Interrater reliability for the abstract screening and full-text screening questions ranged from 0.73 to 0.98 and 0.69 to 0.98, respectively. We located 10 published and 4 unpublished educational interventions that met our criteria. Most programs were in the United States (n = 8) or Canada (n = 5), and almost all targeted residents (n = 12) (see Tables 1 and 2 for descriptions of included programs). Clinical training experiences were often based in primary care or, alternatively, targeted specific populations such as women, people living with addictions or human immunodeficiency virus, or those in rural settings.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Included Sources.

| No. | |

|---|---|

| Publication status | Peer reviewed published = 10 |

| Residency program grey literature = 4 | |

| Country where study conducted | United States = 8 |

| Canada = 5 | |

| Australia = 1 | |

| Psychiatric learner breakdown | Junior residents only = 2 |

| Senior residents only = 5 | |

| Junior and senior residents = 4 | |

| Residents (not specified) = 1 | |

| Staff = 2 | |

| Fellows = 0 | |

| Faculty = 0 | |

| Core or elective | Elective = 6 |

| Core curriculum = 5 | |

| Mix of core + elective = 1 | |

| Not reported = 2 | |

| Type of educational intervention | Didactic only = 3 |

| Clinical placement only = 2 | |

| Didactic + clinical placement = 8 | |

| Didactic + clinical + other = 1 | |

| Other = Research project, joint quality | |

| improvement, practice groups (case-based learning) | |

| Research design (no control groups included any studies) | Noncomparative = 14 (100%) |

| Data collection methods/sources | Self-report quantitative = 13 |

| Self-report qualitative = 2 | |

| Other (patient self-report, partner provider self-report) = 5 | |

| (5 studies had more than one method) | |

| Highest level outcome (Kirkpatrick level) for each study | Level 4b: Patient outcomes = 2 |

| Level 4b: Patient satisfaction = 1 | |

| Level 4a: Organizational outcomes = 1 | |

| Level 2a: Learner perceptions/attitudes = 7 | |

| Level 1: Learner satisfaction = 4 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of Included Integrated Care Training Programs.

| First Author, Year Published | Training Setting(s) | Target Population | Core or Elective | Type of Education | Training ‘Dose’, Duration | Concurrent Trainees | No. of Trainees (Start, End) | Highest Level of Evaluation | MERSQI Scorea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cowley,35 2000 | Family medicine, general internal medicine, global health and HIV, women’s health clinics | Senior residents | Elective | Clinical, didactic | Half-day per week over 12 months or full-day per week over 6 months | None | 14, 14 | Learner perceptions/ attitudes | 9 |

| DeGaetano,36 2015 | Family medicine, addictions clinics (Veterans Affairs) | Junior residents | Core | Clinical | NR, 6 months | None | 15, 15 | Learner perceptions/ attitudes | 6 |

| Engel,37 n.d. | Patient-aligned care team (Veterans Affairs) | Junior, senior residents | Mixed core, elective | Clinical, didactic | Full-time over 4 weeks | Internal medicine residents | 18, 18 | Learner satisfaction | 6.5 |

| Henrich,40 2003 | Inner-city women’s health clinic | Senior residents | Elective | Clinical, didactic | Half-day per week, NR | Ob/Gyn, internal medicine residents | NR | Learner satisfaction | 8 |

| Huang,31 2015 | Nonclinical | Junior, senior residents | NR | Didactic | Two 2-hour modules, plus readings and videos | None | 46, 46 | Learner perceptions/ attitudes | 7.5 |

| Kates,41 2011 | Urban family medicine clinic | Junior, senior residents | Core | Clinical, didactic | Half-day per week over 6 months for junior residents, NR for senior residents | Family medicine residents and staff physicians | 15, 15 | Learner perceptions/ attitudes | 5 |

| McMahon,42 1983 | Psychiatry and family medicine clinic at academic hospital | Junior residents | NR | Other (case-based learning, Balint group, QI, research project) | Monthly didactic, 2-3 times per week case-based learning, NR | Family medicine residents | NR | Learner satisfaction | 6 |

| Merkel,32 n.d. | Rural family medicine clinics via telepsychiatry | Senior residents | Core | Clinical, didactic | Half-day every other week over 1 year | None | NR | Patient satisfaction | 9 |

| Naimer,43 2012 | Psychiatry and family medicine departments at academic hospital | Junior, senior residents | Elective | Clinical, didactic | NR, 1 year | Family medicine residents | 4, 4 | Learner perceptions/ attitudes | 7.5 |

| Ratzliff,38 n.d. | Family medicine clinic | Senior residents | Elective | Clinical, didactic | Half-day per week over 6 to 12 months | None | 19, 19 | Learner perceptions/ attitudes | 7 |

| Rockman,33 2004 | NR | Staff psychiatrists | Elective | Didactic | 2 CME events, NR | General practitioners (including psychotherapists) | 10, NR | Patient outcomes | 5 |

| Sunderji,39 n.d. | Family medicine clinics | Senior residents | Core | Clinical, didactic | 2 days per week over 3 months | Variable; family medicine residents and interprofessional trainees | NR | Learner satisfaction | 6 |

| Sved Williams,34 2006 | NR | Staff psychiatrists | Elective | Didactic | 2 hours | None | 31, 27 | Organizational outcomes | 8 |

| Teshima,44 2015 | Rural family medicine clinics via telepsychiatry from academic children’s hospital | Residents (year NR) | Core | Clinical | Two or more 1- to 2-hour consultations | None | NR, 381 | Learner perceptions/ attitudes | 7.5 |

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MERSQI, Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument; n.d., no date; NR, not reported; QI, quality improvement.

Critical Appraisal of Included Literature

The median MERSQI score for included studies was 7.25 (range, 5-9; see supplemental file). All programs except one31 were limited to a single site, and many had response rates that were low or not reported. Few programs reported on higher order organizational or patient outcomes.32–34 The overall quality of included studies is low to moderate. Despite the prevalent weak study designs and the predominant focus on lower level outcomes (e.g., learner satisfaction and attitudes), it is likely that this body of literature reflects some publication bias toward favourable outcomes, considering that few programs reported any negative outcomes.35–37

Comparison of Included Programs with the Larger Body of Known Canadian and US Programs

Of the 3 educational interventions included in our review and based in Canadian postgraduate training, 2 originated from the University of Toronto residency program, which is the largest residency program by far, and 1 from McMaster University, another moderately sized program also in Ontario. A previous survey of Canadian psychiatry residency programs that we conducted (unpublished observation, n = 13 respondents out of 16 residency programs in 2012) suggests that these experiences are representative of the range of training experiences currently offered across Canada, although the implementation climate would likely differ in Toronto’s large metropolitan academic environment.

With respect to the US residency programs that are known to provide training in integrated care, of the 34 distinct training experiences offered at 27 residency programs, only 3 programs responded to our email invitation, met all inclusion criteria, and are reported here (further information available from the authors upon request). They do not appear to capture the breadth of clinical settings, outcomes, or implementation challenges described in the AADPRT database.

Goals of Training

Programs emphasized learners’ skill development to collaborate with other health care providers outside of specialist psychiatric settings, such as initiating and managing collaborative working relationships, providing direct patient consultation and indirect provider-to-provider consultations, and communicating effectively. Few programs taught knowledge and skills specific to the more empirically supported chronic care models, such as the evidence, supervision of care managers, delivery of measurement-based care, and/or population-based care.31,38

Co-learners

Seven of the 14 programs reported having some other ‘co-learners’ involved besides psychiatrists, such as family medicine or other residents, or practicing primary care physicians; only 1 program included interprofessional health care provider trainees (e.g., social work or psychology), and it did so variably.39 None reported learning objectives or outcomes for these co-learners, nor were they published separately according to a targeted search.

Outcomes Evaluated and Strength of Findings

We identified 39 unique outcomes that represent the ways in which integrated care educational interventions have been evaluated. These included commitment or buy-in to integrated care among all stakeholders (21% of the outcomes measured); learner experience and satisfaction (15%); learner awareness and knowledge (15%); learner skill development (13%); effects on educational resource requirements, such as teachers’ time (5%); structures and processes of care, including collegial/professional networks, communication, and coordination of care (10%); and patient-oriented outcomes such as experience, wait time, or clinical outcomes (21%) (see Table 3 for outcomes by type and strength of finding). No studies used validated rating scales.

Table 3.

Outcomes of Integrated Care Training by Type and Strength of Finding.

| Type of Outcome, % (n) of All Outcomes | Conclusions Can Probably Be Based on the Results | Ambiguous Results; There Appears to Be a Trend | Not Significant or No Conclusions Could Be Drawn |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buy-in to integrated care among diverse stakeholders, 23% (9) | Recruitment and retention of psychiatrists into the IC program | Use of the service (e.g., by PCPs) (±) Referring provider (e.g., PCP) experience, perceptions of advice provided Learner intent to incorporate skills into practice Learner integration into primary care setting (±) Learner intent to practice telepsychiatry in their career |

Learner intention to practice IC in their career PCP perceived need to refer to IC |

| Learner experience, 15% (6) | Experience of providing IC Satisfaction with training in IC |

Recommend the training experience to continue | Perceived supervision quality Perceived relevance to current and future practice Satisfaction with use of telepsychiatry technology Experience of collaboration via telepsychiatry (±) |

| Learner awareness, knowledge, 15% (6) | Knowledge of relationship between physical and mental health Clinical knowledge (of all providers) Knowledge of evidence for IC models Knowledge of telepsychiatry as a useful mode of service delivery to underserved areas |

Exposure to culturally diverse population Learner clarity re: their role (–) |

|

| Learner skill, 13% (5) development | Preparation to function as a psychiatric consultant at the interface with

primary care Assessment and management of mental illnesses Quality of learner documentation |

Assessment and management of mental illness via

telepsychiatry Assessment and management of risk and emergencies via telepsychiatry (±) |

|

| Educational resource requirements, 5% (2) | Minimized duplication of teach efforts across departments Workload of mentoring trainees (–) |

||

| Communication and coordination of care, 10% (4) | More collegial relationships Improved communication and continuity of care |

Enhanced professional practice network PCP access to specialist opinion |

|

| Patient-oriented outcomes, 20% (8) | Decrease in patient symptoms Patient experience of care providers’ helpfulness Decrease in wait times Patient engagement in care planning Patient experience of clinic/logistics |

PCP perception of overall improved patient care Patient experience of telepsychiatry |

All outcomes positive unless noted (–) for negative outcomes or (±) for conflicting studies. IC, integrated care; PCP, primary care provider.

The overall low to moderate quality of studies included in this review was reflected in our assignment of the strength of the findings. Of the 39 unique outcomes extracted from the studies, 36% (14) were identified as of the lowest strength (not significant or no conclusions could be drawn), 56% (22) were slightly better (ambiguous results, appears to be a trend), 8% (3) were stronger still (conclusions can probably be based on the results), and none were of the highest strength (results are clear and very likely).

Descriptions of and Trends in Effective Integrated Care Training

While the educational interventions included in this review are markedly heterogeneous, there are several major variants in the types of interventions: a) mentoring networks whereby psychiatrists provide case-based input (e.g., telephone, fax, or e-consultation) upon PCPs’ request, b) brief didactic events, and c) longitudinal supervised clinical experiences for residents.

Mentoring networks

Three studies provided brief training to practicing psychiatrists or residents to provide just-in-time case-based consultation and ongoing mentorship to PCPs.33,34,43 Two of these studies also trained the PCPs together with the psychiatrists, thus jointly preparing mentors and mentees to make use of the consultative relationship through fostering rapport, raising awareness of the service and how to use it appropriately, and addressing medicolegal issues, including confidentiality and documentation.33,43 In all 3 studies, there were trends toward use of the service and PCPs’ perceptions of the utility of the advice (conclusions could reasonably be drawn in Naimer et al.43). In 2 studies, there were trends toward positive impacts on PCPs’ self-reported knowledge33,34 and in 1 case on PCPs’ self-reported time to implement optimal treatment.33 Conclusions could reasonably be drawn that one of these programs was successful in recruiting and retaining psychiatrists to provide case-based provider-to-provider consultation upon request by PCPs.34

Brief didactic teaching

Two programs consisted solely of didactic teaching to residents, including interactive workshops with readings, videos, case-based discussions, and/or hospital-based rounds.31,42 These were provided for as little as two 2-hour modules to as much as twice per week for 1 academic year. Of note, 1 of these programs focused on the collaborative/chronic care model.31 In the results of our analysis, few conclusions could be drawn about impact; learners may be willing to incorporate new techniques but may prefer greater realism (e.g., case-based learning and role-plays).

Longitudinal supervised clinical experiences

Six studies outlined longitudinal clinical workplace activities in primary care settings, on average 6 months in duration (ranging from a half to a full day per week for between 3 and 12 months).32,35,36,38,39,41 Residents provided consultation to PCPs and their patients in person or via telemedicine. Most programs supplemented this with didactic content about integrated care models and effective approaches for collaboration. Some programs showed trends toward satisfaction with the training experience,39 improved resident knowledge and skills (e.g., empirically supported models of integrated care, using screening and monitoring tools, supporting care managers),38 impact on future career plans,38 and patient experience.32 However, in other cases, no conclusions could be drawn.36,41,45

Implementation Challenges

Many authors described challenges in training residents within models of care that are complex, evolving, and difficult to implement and sustain in varied ‘real-world’ clinical settings.19,32,35–37,39,40,41 Infrastructural barriers were prevalent, such as a) sustainability of funding,32,37,40 b) physical space that was inadequate or not conducive to collaborative interactions,32,35,37 c) insufficient staffing to maintain the service, and d) staff lacking interest and ability to role-model good consultation-liaison attitudes and skills.32,37,41 Engagement and support of collaborators (e.g., PCPs) were repeatedly flagged as crucial to ensure stability of the service and to develop attitudes conducive toward collaboration with psychiatry trainees.32,35,41 In the absence of this type of buy-in, it can be difficult for trainees to have clarity about their roles.35

Discussion

In this study, we rigorously review published and unpublished literature describing training programs that prepare current or future psychiatrists to provide integrated care. We have distilled training programs’ goals, pedagogical methods, outcomes, and implementation challenges hampering sustainability and spread. We balanced the desire to illuminate key issues in integrated care training with judicious interpretation of included studies, given the overall heterogeneity and low to moderate quality of the studies. Thus, we provide a comprehensive and well-considered overview of the current state of the field. To our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind and can provide a useful guide to academic and clinical leaders in this area.

Several limitations common to systematic reviews merit consideration. The topic under study is at the intersection of several complex concepts, and the search terms and parameters we used would have influenced the integrated care educational interventions that we located, with some risk of unintentional omission of relevant literature. We suspect some degree of publication bias has also affected the availability and quality of information pertaining to the defined research question. We attempted to mitigate this by seeking out unpublished literature, but we were limited by the low response rate among residency programs. Another limitation is the overall low to moderate methodological rigor of available studies. We critically appraised each study design using the MERSQI and carefully considered the strength of each outcome.

Based on the existing literature, it is difficult to determine which, if any, approaches to training improve educational, patient, or health system outcomes. This is concerning considering that training is already widespread and has been resource intensive to implement in already overburdened curricula. There is a strong appetite across Canada for practical recommendations to facilitate implementation and improvement of training across Canada. Although we are hard-pressed to make such recommendations based on empirical knowledge from this systematic review, our results do provide some direction for this important but immature field. Drawing upon a combination of this scientific knowledge, our pragmatic knowledge as providers of integrated care (N.S., P.B., A.G.R., A.C.) and our experiential knowledge as integrated care educators and leaders (N.S., A.G.R.), clinical supervisors (N.S., A.C.), and learners (P.B., D.H.), we suggest several recommendations to advance psychiatric training in integrated care, with an emphasis on postgraduate training and with the caution that further evaluation is needed (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Practical Recommendations to Improve Postgraduate Psychiatric Training.

| Aspect of Training | Specific Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Clinical exposure | We recommend a longitudinal clinical experience that will afford residents ample

time to experience and reflect on the delivery of integrated care, as well as

opportunities for its improvement (e.g., 1 day per week for 6 or ideally 12

months); this approach may also contribute to developing and sustaining emerging

integrated care clinical programs whereby organizational and interprofessional

relationships are formed and the setting and its staff become an ongoing resource

for learning. By working from a defined set of integrated care competencies that can be attained in a variety of settings,14 it is possible to create ‘minimum specifications’ for training settings (ours are available upon request). This can ensure a robust and sufficiently standardized experience while diversifying and expanding the range of different training contexts, including primary care and community agency settings, telemental health clinics, geriatric long-term care facilities, schools, and child protection agencies.19,47 Enabling senior residents to demonstrate competency in multiple domains simultaneously (e.g., geriatric or child psychiatry and integrated care) can enhance feasibility of implementation and encourage residents to consider working in integrated care regardless of their intended area of future practice.19 While mentorship networks appear promising in the reviewed literature,33,34,43 only 1 study has applied this in postgraduate training.43 We suggest that they should not be used as an exclusive strategy for training residents, as it may be difficult to provide an adequate ‘dose’ of training in this model or to develop the range of practical skills needed beyond mentoring. |

| Core curriculum | A strong nonclinical curriculum can mitigate gaps in the clinical training

experience (e.g., related to the evidence-to-practice gap in the models of

integrated care),31,48 emphasize topics relevant to transitioning to practice (e.g., leadership,

career planning, managing patient safety, and medicolegal liability in

collaborative practice), and ideally introduce feedback loops that engage faculty

in helping residents apply the curriculum learning to the clinical

environment. A ‘flipped classroom’ model49,50 can engage senior residents as adult learners and minimize the faculty teaching burden, which can be particularly high if there are few faculty equipped to teach this content.32,35,41 However, ensuring adequate time for the independent study component is key to resident acceptance, and there is a need for further evaluation of this approach.51 |

| Assessment | Assessment should be congruent with the move to competency-based education, focused, and relevant to integrated care (e.g., multisource feedback, case-based application of population-based care concepts, written or oral application of learning about evidence-based models of integrated care).52 |

| Faculty development | The importance of faculty development cannot be overstated. Given the newness of integrated care training in Canada, faculty may not have been exposed to this mode of practice during their own training and/or they may not be familiar with teaching and assessing it. An initial ‘bolus’ of preparation may be needed, ideally accompanied by longitudinal peer group learning and support. |

| Implementation issues and change management | It is crucial that any efforts to expand or improve training anticipate and

proactively address issues with funding models, physical space, and readiness of

the clinical training environment (e.g., culture, stability).32,35,37,40,41

This requires at least 1 champion with dedicated time as it involves extensive engagement work with diverse stakeholders, including faculty, collaborating primary care and community sites, academic leaders, and learners.32,35,41 Ideally, collaboration with primary care and/or community partners should be built into all aspects of curriculum, assessment, and faculty development, if there is willingness and capacity (or if this can be cultivated over time). |

Beyond these practical recommendations, we wish to offer a few general observations and broader recommendations. Training should better align with empirically supported models of integrated care, and reciprocally, integrated care training experiences require better evaluation. This issue runs parallel to the overall advancement of integrated care, where further work is needed to a) disseminate and implement evidence-informed integrated care models (‘evidence-based practice’) and b) engage practitioners in participatory evaluation and improvement of what has been implemented and the creation of generalizable knowledge (‘practice-based evidence’).46

This necessary progression in the field can be achieved by explicitly orienting integrated care training toward how to simultaneously work in and improve integrated care models.14 Training will need to include knowledge of the evidence in integrated care, population health principles, chronic disease management, stepped care models, health policy, and skills in collaborative leadership, program consultation, and using patient- and clinic-level data to guide improvements in practice (i.e., quality measurement and improvement).13,14 These competencies align with a modern conceptualisation of basic science (i.e., incorporating improvement science) and clinical science (i.e., leadership skills for system-based practice), which learners can attain while ‘actively participat[ing] in high-quality institutional initiatives to improve patient outcomes’.53 Among the studies included in our review, only 2 were specifically oriented toward teaching the collaborative/chronic care model, including population-based care and case finding (both programs)31,38 and quality improvement and leadership (1 program).38

Furthermore, improvements to integrated care training will necessitate much greater attention to faculty development. Despite an exhaustive search, we did not identify any initiatives aimed at faculty development in integrated care. This is particularly concerning considering a lack of sufficient and skilled supervisors is a widely identified barrier to implementing integrated care training.19,32,37,41 Faculty need all the same competencies as residents plus the ability to teach and assess in this area.

Co-learning of residents and faculty together may be a worthwhile approach to efficiently build capacity for integrated care training across Canada. For example, an innovative and well-received experiential co-learning curriculum in quality improvement (QI) for internists at the University of Toronto could serve as a model. It enabled faculty to learn QI and/or learn to teach and mentor residents in QI flexibly according to their readiness and interest, thus training up faculty at the same time as teaching current residents.54 Following this model, psychiatry faculty and residents could jointly engage in a mentored effort to improve integrated care implementation in their clinical setting, thus harnessing the benefits of experiential learning, workplace-based learning, communities of practice, and mentorship.55,56 Findings from the co-learning QI curriculum also suggest potential benefits for collegial networking and professional identity formation.54 Having faculty and residents co-produce learning could also help reduce dissonance between the curriculum as planned by clinical and education leaders, as taught by supervisors and collaborators and as experienced by learners.57–59

Concurrently, training in integrated care should better prepare all members of the integrated care team and do so jointly. Many of the studies included in our review involved co-learners of other disciplines in the training setting alongside psychiatric learners, yet their roles and learning objectives and outcomes were rarely described. Individual competencies for care managers and other team members have been suggested and developed into curricula that go beyond the scope of this review, particularly in the United States, where the collaborative/chronic care model is seeing more rapid implementation.13,15,16 Equally important is the concept of team competence. Successful integrated care is the result of effective interactions between diverse professionals,60–62 and the literature on health care teams increasingly recognizes that ‘competent individual professionals can—and do, with some regularity— combine to create an incompetent team’.63 Pedagogy in health care professionals’ education has yet to reflect the need to train and evaluate training outcomes together.

Finally, clinical training experiences in integrated care require better evaluation and reporting. Clinician innovators and educators should consider a) using a framework for integrated care evaluation that can help identify improvement opportunities in the clinical training environment,9,64 b) focusing initially on implementation evaluation to assess what is actually occurring in the training setting and why,65and c) using a logic model to guide outcome evaluation of practice and organizational changes that are linked to the educational and clinical care processes that have been implemented.23,66 With these elements in place, quasi-experimental study designs for ‘real-world’ clinical practice settings, such as time trends analysis and qualitative studies, could yield compelling new insights.

Conclusion

This systematic review provides an overview of current educational initiatives in integrated care that can be used to improve the quality of psychiatric training. We highlight the common approaches to training and their challenges, as well as the overall limitations of the current literature. We propose that the following are needed: a competency-based approach to clinical training, curricula and assessment, faculty development, team training, and the application of QI methods. The advancement of training and the implementation of evidence-informed integrated mental health care are reciprocally linked and will be aided by data-informed reflection on practice, harnessing improvement and implementation sciences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Robyn Butcher for assistance with crafting the database searches, Ms. Carolyn Ziegler for peer reviewing the database searches, Dr. Claudia Reardon for sharing the AADPRT database of US residency programs providing training in integrated care, and Dr. Kathleen Broad for assistance with screening citations.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Nadiya Sunderji, MD, MPH, FRCPC  http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0188-0658

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0188-0658

References

- 1. Mental Health Commission of Canada. Changing directions, changing lives: the mental health strategy for Canada. Calgary (AB): Mental Health Commission of Canada; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kates N, Mazowita G, Lemire F, et al. The evolution of collaborative mental health care in Canada: a shared vision for the future. Can J Psychiatry Rev Can Psychiatr. 2011;56(5):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vanderlip ER, Rundell J, Avery M, et al. Dissemination of integrated care within adult primary care settings: the collaborative care model. 2016. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/professional-interests/integrated-care/collaborative-care-model (accessed September 14, 2016).

- 4. Chung H, Rostanski N, Glassberg H, et al. Advancing integration of behavioral health into primary care: a continuum-based framework. 2016. https://uhfnyc.org/publications/881131. (accessed June 20, 2017).

- 5. Woltmann E, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron B, et al. Comparative effectiveness of collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions across primary, specialty, and behavioral health care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(8):790–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD006525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, et al. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(21):2314–2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Foy R, Hempel S, Rubenstein L, et al. Meta-analysis: effect of interactive communication between collaborating primary care physicians and specialists. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(4):247–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sunderji N, Ghavam-Rassoul A, Ion A, et al. Driving improvements in the implementation of collaborative mental health care: a quality framework to guide measurement, improvement and research. 2016. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312539646_Driving_Improvements_in_the_Implementation_of_Collaborative_Mental_Health_Care_A_Quality_Framework_to_Guide_Measurement_Improvement_and_Research. (accessed February 26, 2017).

- 10. Kroenke K, Unutzer J. Closing the false divide: sustainable approaches to integrating mental health services into primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(4):404–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. American Psychiatric Association Council on Medical Education and Lifelong Learning. Training psychiatrists for integrated behavioral health care: official actions. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Association; 2014. http://www.psychiatry.org/network/councils-andcommittees/council-on-medical-education-and-lifelong-learning (accessed June 21, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization, World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA). Integrating mental health into primary care: a global perspective. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization and World Organization of Family Doctors; 2008. http://www.who.int/mental_health/policy/services/mentalhealthintoprimarycare/en/ (accessed November 10, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ratzliff A, Norfleet K, Chan YF, et al. Perceived educational needs of the integrated care psychiatric consultant. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(4):448–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sunderji N, Waddell A, Gupta M, et al. An expert consensus on core competencies in integrated care for psychiatrists. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;41:45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hoge MA, Morris JA, Laraia M, et al. Core competencies for integrated behavioral health and primary care. Washington (DC: ): SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miller BF, Gilchrist EC, Ross KM, et al. Core competencies for behavioral health providers working in primary care. Prepared from the Colorado Consensus Conference Feb 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17. The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. Specialty training requirements in psychiatry. 2009. http://rcpsc.medical.org/residency/certification/training/psychiatry_e.pdf (accessed February 26, 2012).

- 18. Moran M. Federal grant allows free training in collaborative care. Psychiatrics News 2016. http://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.pn.2016.2b7 (accessed October 15, 2017).

- 19. Sunderji N, Jokic R. Integrated care training in Canada: challenges and future directions. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(6):740–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kates N. Shared/collaborative mental health care In: Leverette JS, Hnatko G, Persad E, eds. Approaches to postgraduate education in psychiatry in Canada: what educators and residents need to know. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Psychiatric Association; 2009. 183–197. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sunderji N, Ghavam-Rassoul A, Ion A, et al. Training current and future psychiatrists in collaborative mental health care: a systematic review. 2014. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42014010295 (accessed August 5, 2015).

- 22. Miller BF, Kessler R, Peek CJ, Kallenberg GA. A framework for collaborative care metrics: a national agenda for research in collaborative care. 2011. http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/final-reports/collaborativecare/collab2.html. (accessed March 31, 2013).

- 23. Kirkpatrick DL. Evaluating training programs. New York: Tata McGraw-Hill Education; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cook DA, Reed DA. Appraising the quality of medical education research methods: the medical education research study quality instrument and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale–Education. Acad Med. 2015;90(8):1067–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). Qualitative Research Checklist. 2017. http://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/dded87_25658615020e427da194a325e7773d42.pdf (accessed September 16, 2017).

- 26. Colthart I, Bagnall G, Evans A, et al. The effectiveness of self-assessment on the identification of learner needs, learner activity, and impact on clinical practice: BEME Guide no. 10. Med Teach. 2008;30(2):124–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hammick M, Dornan T, Steinert Y. Conducting a best evidence systematic review. Part 1: From idea to data coding. BEME Guide No. 13. Med Teach. 2010;32(1):3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Forman J, Damschroder LJ. Qualitative content analysis In: Jacoby L, Siminoff L, eds. Empirical methods for bioethics: a primer. Amsterdam: Elsevier JAI Press; 2008:39–62. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huang H, Barkil-Oteo A. Teaching collaborative care in primary care settings for psychiatry residents. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(6):658–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Merkel R. UVA training residents in integrated psychiatry.

- 33. Rockman P, Salach L, Gotlib D, et al. Shared mental health care: model for supporting and mentoring family physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2004;50:397–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sved Williams A, Dodding J, Wilson I, et al. Consultation-liaison to general practitioners coming of age: the South Australian psychiatrists’ experience. Australas Psychiatry. 2006;14(2):206–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cowley DS, Katon W, Veith RC. Training psychiatry residents as consultants in primary care settings. Acad Psychiatry. 2000;24(3):124. [Google Scholar]

- 36. DeGaetano N, Greene CJ, Dearaujo N, et al. A pilot program in telepsychiatry for residents: initial outcomes and program development. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(1):114–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Engel A. Collaborative care training at Veterans Affairs Boston Medical Center.

- 38. Ratzliff A. University of Washington collaborative care rotation. http://uwaims.org/training-consulting_psychiatrists_residents.html.

- 39. Sunderji N. University of Toronto—collaborative mental health care training for residents. http://www.psychiatry.utoronto.ca/education/postgraduate-program/integrated-mental-health-care-imhc.

- 40. Henrich JB, Chambers JT, Steiner JL. Development of an interdisciplinary women’s health training model. Acad Med. 2003;78(9):877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kates N. Sharing mental health care: training psychiatry residents to work with primary care physicians. Psychosomatics. 2000;41(1):53–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McMahon T, Gallagher RM, Little D. Psychiatry-family practice liaison: a collaborative approach to clinical training. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1983;5(1):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Naimer M, Peterkin A, McGillivray M, et al. Evaluation of a collaborative mental health program in residency training. Acad Psychiatry. 2012;36(5):411–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Teshima J, Hodgins M, Boydell KM, Pignatiello A. Resident evaluation of a required telepsychiatry clinical experience. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(2):348–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cowley D, Dunaway K, Forstein M, et al. Teaching psychiatry residents to work at the interface of mental health and primary care. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(4):398–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Green LW. Making research relevant: if it is an evidence-based practice, where’s the practice-based evidence? Fam Pract 2008;25(suppl 1):i20–i24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto. Integrated mental health care core experiences, 2018-2019. http://www.psychiatry.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/University-of-Toronto-Integrated-Mental-Health-Care-Core-Experiences-for-2018-19.pdf (accessed January 31, 2018).

- 48. Sunderji N, Kurdyak PA, Sockalingam S, et al. Can collaborative care cure the mediocrity of usual care for common mental disorders? Can J Psychiatry Rev Can Psychiatr. doi: 10.117/0706743717748884. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Moffett J. Twelve tips for “flipping” the classroom. Med Teach. 2015;37(4):331–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. McLaughlin JE, Roth MT, Glatt DM, et al. The flipped classroom: a course redesign to foster learning and engagement in a health professions school. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2014;89(2):236–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chen F, Lui AM, Martinelli SM. A systematic review of the effectiveness of flipped classrooms in medical education. Med Educ. 2017;51(6):585–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sunderji N, Waddell A. Close encounters of the integrated kind: a collection of assessment tools for integrated and collaborative care. Presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Academic Psychiatry. Sept 24 2016 Puerto Rico, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lucey CR. Medical education: part of the problem and part of the solution. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(17):1639–1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wong BM, Goldman J, Goguen JM, et al. Faculty-resident “co-learning”: a longitudinal exploration of an innovative model for faculty development in quality improvement. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2017;92(8):1151–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Steinert Y. Faculty development for postgraduate education—the road ahead. Ottawa (ON): Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada, Collège des Médecins du Québec, College of Family Physicians of Canada, Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2011. https://afmc.ca/pdf/fmec/21_Steinert_Faculty%20Development.pdf (accessed October 15, 2017).

- 56. Jolly B. Faculty development for organizational change In: Steinert Y, ed. Faculty development in the health professions: a focus on research and practice, innovation and change in professional education. Dordrecht (Netherlands): Springer Science + Business Media; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Coles CR, Grant JG. Curriculum evaluation in medical and health-care education. Med Educ. 1985;19(5):405–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Harden RM. AMEE Guide No. 21: curriculum mapping: a tool for transparent and authentic teaching and learning. Med Teach. 2001;23(2):123–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Snelgrove N, Sunderji N. Forthcoming 2018. Training Specialists as Consultants Integrated into Primary Care. Med Educ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lingard L. Rethinking competence in the context of teamwork In: Hodges B, Lingard L, eds. The question of competence: reconsidering medical education in the twenty-first century. Ithaca (NY: ): Cornell University Press; 2012:42–69. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Raney L, Lasky G, Scott C. The collaborative care team in action. In: Raney L, ed. Integrated care: working at the interface of primary care and behavioral health. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015:17–42. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ratzliff A, Unützer J, Katon W, et al. Integrated care: creating effective mental and primary health care teams. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley; 2016:318. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lingard L. What we see and don’t see when we look at “competence”: notes on a god term. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2009;14(5):625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The Academy for Integrating Behavioral Health and Primary Care. https://www.ahrq.gov/cpi/about/otherwebsites/integrationacademy.ahrq.gov/index.html.

- 65. Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, et al. Implementation research: a synthesis of the literature. FMHI Publication #231. Tampa: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, The National Implementation Research Network; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 66. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office of the Director, Office of Strategy and Innovation. Introduction to program evaluation for public health programs: a self-study guide. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2005. http://www.cdc.gov/eval/guide/index.htm (accessed October 25, 2012). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.