Abstract

The bystander effect, the reduction in helping behavior in the presence of other people, has been explained predominantly by situational influences on decision making. Diverging from this view, we highlight recent evidence on the neural mechanisms and dispositional factors that determine apathy in bystanders. We put forward a new theoretical perspective that integrates emotional, motivational, and dispositional aspects. In the presence of other bystanders, personal distress is enhanced, and fixed action patterns of avoidance and freezing dominate. This new perspective suggests that bystander apathy results from a reflexive emotional reaction dependent on the personality of the bystander.

Keywords: bystander effect, helping behavior, empathy, sympathy, personal distress

When people are asked whether they would spontaneously assist a person in an emergency situation, almost everyone will reply positively. Although we all imagine ourselves heroes, the fact is that many people refrain from helping in real life, especially when we are aware that other people are present at the scene. In the late 1960s, John M. Darley and Bibb Latané (1968) initiated an extensive research program on this so-called “bystander effect.” In their seminal article, they found that any person who was the sole bystander helped, but only 62% of the participants intervened when they were part of a larger group of five bystanders. Following these first findings, many researchers consistently observed a reduction in helping behavior in the presence of others (Fischer et al., 2011; Latané & Nida, 1981). This pattern is observed during serious accidents (Harris & Robinson, 1973), noncritical situations (Latané & Dabbs, 1975), on the Internet (Markey, 2000), and even in children (Plötner, Over, Carpenter, & Tomasello, 2015).

Three psychological factors are thought to facilitate bystander apathy: the feeling of having less responsibility when more bystanders are present (diffusion of responsibility), the fear of unfavorable public judgment when helping (evaluation apprehension), and the belief that because no one else is helping, the situation is not actually an emergency (pluralistic ignorance). Although these traditional explanations (Latané & Darley, 1970) cover several important aspects (attitudes and beliefs), other aspects remain unknown, unexplained, or ignored in studies of the bystander effect, including neural mechanisms, motivational aspects, and the effect of personality. Indeed, the only hit for the keyword “personality” in a recent overview (Fischer et al., 2011) was for journal names in the reference list (e.g., Journal of Personality and Social Psychology). Consequently, it seems fair to say that the “literature has remained somewhat ambiguous with regard to the relevant psychological processes” (Fischer et al., 2011, p. 518). Here, we highlight recent neuroimaging and behavioral studies and sketch a new theoretical model that incorporates emotional, motivational, and dispositional aspects and highlights the reflexive aspect of the bystander effect.

Neural Mechanisms of Bystander Apathy

Can neuroimaging studies inform the investigation of the bystander effect? What are the neural mechanisms underlying bystander apathy? In view of traditional explanations, one would expect to find the involvement of brain regions that are important for decision making. Yet emerging evidence suggests that certain forms of helping behavior are automatic or reflexive (Rand, 2016; Zaki & Mitchell, 2013), and recent neuroimaging studies without a bystander focus already propose the automatic activation of preparatory responses in salient situations. Observing a threatening confrontation between two people activates the premotor cortex independent of attention (Sinke, Sorger, Goebel, & de Gelder, 2010) or focus (Van den Stock, Hortensius, Sinke, Goebel, & de Gelder, 2015). This raises the question of whether the absence of helping behavior is a cognitive decision or follows automatically from a reflexive process.

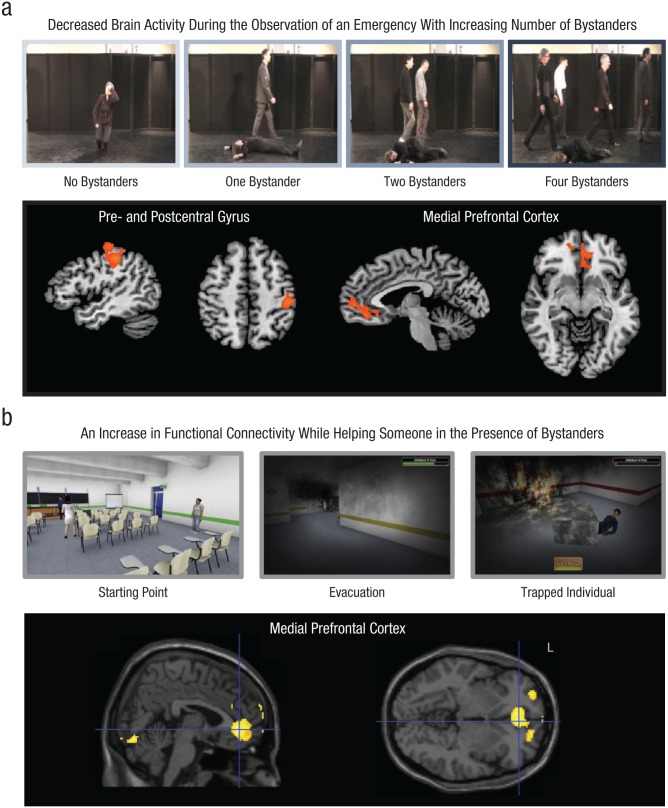

A recent functional MRI (fMRI) study directly mapped neural activity as a function of the number of bystanders present in an emergency situation (Hortensius & de Gelder, 2014). Participants watched an elderly woman collapsing to the ground alone or in the presence of one, two, or four bystanders. Activity increased in vision- and attention-related regions, but not in the mentalizing network. When participants witnessed emergencies with increasing numbers of bystanders, a decrease in activity was observed in brain regions important for the preparation to help: the pre- and postcentral gyrus and the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC; Fig. 1a). The MPFC is implicated in a diverse set of emotional and social processes. One proposal for an overarching role is mapping of situation-response association (Alexander & Brown, 2011; Euston, Gruber, & McNaughton, 2012), coding the link between an event (e.g., an emergency) and corresponding responses (in this case, helping behavior). Activity in the MPFC has been linked to prosocial behavior (Moll et al., 2006; Rilling et al., 2002; Waytz, Zaki, & Mitchell, 2012), such as helping friends and strangers on a daily basis (Rameson, Morelli, & Lieberman, 2012).

Fig. 1.

Neural activity as it relates to bystander apathy. In a functional magnetic resonance imaging experiment testing bystander apathy (a), participants saw an elderly woman collapsing on the ground in the presence of no, one, two, or four bystanders. Still images from the videos are shown. The decrease in activity in the pre- and postcentral gyrus and the medial prefrontal cortex during the witness of an emergency with increasing number of bystanders is shown. In a virtual reality experiment (b), participants had to evacuate a burning building. During the evacuation, they encountered a trapped individual whom they could help or not. Still images from the virtual reality environment are shown. Increased functional coupling of the medial prefrontal cortex within the anterior part of the default-mode network in individuals who helped compared with individuals who did not help is shown. Panel (a) was adapted from Hortensius and de Gelder (2014), and panel (b) was adapted from Zanon, Novembre, Zangrando, Chittaro, and Silani (2014); both are reproduced with permission from Elsevier.

Using a scenario similar to those used in early bystander studies, Zanon, Novembre, Zangrando, Chittaro, and Silani (2014) showed the importance of the MPFC for helping behavior during a life-threatening situation. In an experiment using virtual reality, participants and four bystanders had to evacuate a building that caught on fire. While doing so, they encountered a trapped individual whom they could help. People who offered to help (compared with those who refrained from helping) showed greater engagement of the MPFC within the anterior default-mode network (Fig. 1b). However, can this association be quantified as reflexive or reflective? A recent study suggests that computations underlying choices with a focus on other people’s needs are faster, or reflexive, compared with computations of choices with a selfish focus (Hutcherson, Bushong, & Rangel, 2015). Both of these choices are sustained by the MPFC. Recent evidence suggests that coding of reflexive responses to situations within this area might depend on experience and personality. When cognition was restricted while participants observed people in distress, activity in the MPFC did not decrease for people with higher levels compared with people with lower levels of dispositional empathy (Rameson et al., 2012). Together, these recent findings provide a first indication of the neural mechanism underlying bystander apathy and point to a possible mechanism similar to a reflex that determines the likelihood of helping.

Dispositional Influences on Bystander Apathy

The first experimental bystander study found no effect of dispositional levels of social-norm following on bystander apathy (Darley & Latané, 1968), and since then the role of personality factors has largely been ignored. The general notion is that behavior is dominated by situational factors rather than by personality; thus bystander apathy is present in everyone. This contrasts with other research areas, in which the impact of personality—systematic interindividual differences consistent across time and situation—on helping behavior have been widely appreciated (Graziano & Habashi, 2015). Sympathy and personal distress have been identified as two dispositional factors that influence helping behavior (Batson, Fultz, & Schoenrade, 1987; Eisenberg & Eggum, 2009). Sympathy is an other-oriented response that encompasses feelings of compassion and care for another person. The contrasting and automatic reaction of personal distress relates to the observer’s self-oriented feelings of discomfort and distress. In stark contrast to personal distress, helping behavior driven by sympathy is not influenced by social factors such as social evaluation or reward (Fultz, Batson, Fortenbach, McCarthy, & Varney, 1986; Romer, Gruder, & Lizzadro, 1986).

Inspired by these findings, we studied the interplay between the bystander effect and a disposition to experience sympathy and personal distress by directly and indirectly probing the motor cortex while participants observed an emergency (Hortensius, Schutter, & de Gelder, 2016). As predicted by previous literature, both sympathy and personal distress were related to faster responses to an emergency without bystanders present. However, only personal distress predicted the negative effect of bystanders during an emergency. Further testing showed that this association between personal distress and the bystander effect relates to a reflexive—but not reflective—preparation to help. Consistent with the previous neuroimaging findings, bystander apathy is not the result of a cognitive decision to act; rather, it is dependent on a mechanism similar to a reflex, especially for people with a disposition to experience personal distress.

The reflexive aversive reactions to the suffering of another person are closely related to behavioral avoidance and inhibition. Indeed, state and trait avoidance-related motivations influence bystander apathy (van den Bos, Müller, & van Bussel, 2009; Zoccola, Green, Karoutsos, Katona, & Sabini, 2011). When people are reminded to act without inhibition, thereby temporally shifting the balance between approach and avoidance motivations, helping behavior occurs faster and even increases in bystander situations (van den Bos et al., 2009). Behavioral inhibition is sustained by subcortical brain regions (e.g., amygdala) and cortical brain regions (e.g., motor and prefrontal areas) that act depending on situation and disposition (McNaughton & Corr, 2004). For example, a recent study showed the dynamic interplay between behavioral inhibition, helping behavior, and personality (Stoltenberg, Christ, & Carlo, 2013). Variation in the serotonin neurotransmitter system, a crucial modulator of behavioral inhibition, affected helping behavior, and this relation was mediated by dispositional levels of social inhibition. Thus, bystander apathy is likely to be the result of a personality-dependent mechanism that is similar to a reflex.

Bystander Apathy as the Result of a Motivational System

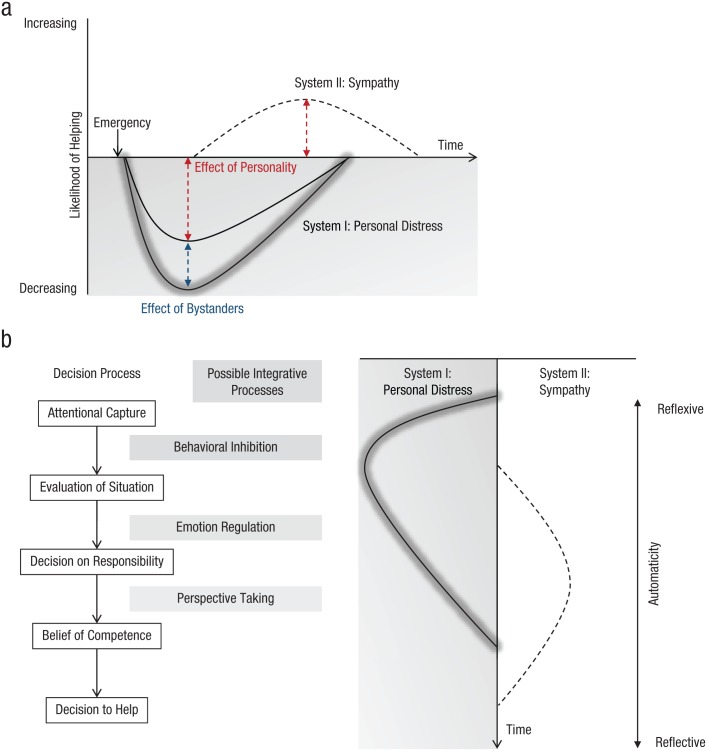

These findings dovetail with a motivational model described by Graziano and his colleagues (Graziano & Habashi, 2010, 2015) in which two evolutionarily conserved but opposing motivational systems with fixed behavioral consequences are activated in sequence when people encounter an emergency. Feelings of personal distress and sympathy are related to the first and second systems, respectively. The instantaneous response to an emergency is a feeling of distress and activation of the fight-freeze-flight system. Under these conditions, helping behavior does not occur, and the behavioral response is limited to avoidance and freeze responses. Over time, a slower feeling of sympathy arises together with the activation of a reflective second system. This counteracts the fixed action patterns of the first system. The likelihood that helping behavior will occur is the net result of these two systems, and helping behavior is promoted by the second system. Feelings of personal distress and sympathy are present in everyone, but the dispositional levels of these feelings and strength of these two systems vary between individuals (Graziano & Habashi, 2010, 2015). The presence of bystanders during an emergency selectively increases the activity of the first system (Fig. 2a). This situational increase in personal distress, combined with dispositional levels of personal distress, increases the activation of the fight-freeze-flight system and results in a reduced likelihood of helping. Indeed, higher levels of personal distress decrease helping behavior when the possibility of escaping the situation is easy (Batson et al., 1987). Ultimately, bystander apathy occurs as the consequence of an inhibitory response, leading people to try to avoid the situation, but this is not a conscious decision.

Fig. 2.

A motivational and integrated account of bystander apathy. Helping behavior is the net result of two opposing processes (Graziano & Habashi, 2010). When people encounter an emergency, self-centered feelings of personal distress arise, and the fight-freeze-flight system is activated; helping behavior does not occur (a). Only with the opposing other-oriented feeling of sympathy and the activation of the second system does the likelihood of helping increase. The strength of the two systems is the sum of dispositional and situational influences. The strength of System I is increased for people with a disposition to experience personal distress in response to an emergency. Because the presence of bystanders results in an additional increase in the strength and dominance of System I, individuals with a disposition to experience personal distress in response to an emergency are more prone to bystander apathy. Intermediate processes can be described to reconcile cognitive and motivational accounts of bystander apathy. The decision process, as first put forward by Latané and Darley (1970), consists of the cognitive steps that occur from the initial attentional capture and evaluation of the emergency, to the decision of responsibility and competence, and ultimately to the decision to provide help (b). These processes can be mediated by the integrative processes of behavioral inhibition, emotion regulation. and perspective taking, which are at first driven by the reflexive system of personal distress and later by the reflective system of sympathy. Ultimately, these personality- and situation-dependent processes can increase or decrease the likelihood of a person providing help during emergency situations involving bystanders.

The Ultimate Cause of Bystander Apathy

Although this perspective provides new insight into the proximate cause of bystander apathy, it also allows for speculation on its ultimate cause. Why is the motivation to help dependent on the number of bystanders? Perhaps because, for the best outcome, only the fittest individual (strongest, most experienced, etc.) should provide help and others should not, or at least they should help more cautiously. The training of firefighters and other first responders directly follows these principles: Only well-trained individuals are allowed to help, and trainees are excluded. Taking into account the composition and size of the bystander group is crucial in providing efficient help that maximizes individual survival. This might already be reflected in the calculations within the motivational system (Francis, Gummerum, Ganis, Howard & Terbeck, 2017). Apathy in novel situations or with unknown bystanders could be the consequence of these calculations. There is indirect evidence for this suggestion: Bystander apathy is reduced when bystanders know each other (Fischer et al., 2011), and an individual’s competence relative to other bystanders influences the occurrence of helping behavior (Bickman, 1971; Ross & Braband, 1973). Future studies should formally test the effect of group composition (i.e., known identity, expertise) on the calculations within the motivational system. Are increased levels of personal distress during bystander situations a way to prevent inadequate helping behavior?

An Integrative Perspective on Bystander Apathy

This is not to say that previous decision-based explanations are obsolete. Cognitive, situational, and dispositional explanations are not mutually exclusive, and a multilevel approach is crucial in understanding helping behavior and the lack thereof. Thoughts and feelings are part of every responsive bystander, and the motivational processes described could precede or influence the decision to help (Hortensius, Neyret, Slater & de Gelder, 2018). Latané and Darley (1970) describe a five-step process during bystander situations: The potential emergency (a) captures the attention of the individual, who (b) evaluates the emergency, (c) decides on responsibility and (d) belief of competence, and then ultimately (e) makes the decision to help or not. However, these calculations in the decision-making process do not necessarily have to occur at a reflective, cognitive level (Garcia, Weaver, Moskowitz, & Darley, 2002) and can also reflect the outcome of reflexive or intermediate processes.

Several intermediate processes can reconcile the previous reflective and present reflexive explanations but warrant further empirical confirmation (Fig. 2b). These processes—behavioral inhibition, emotion regulation, and perspective taking—stem directly from the overarching motivational systems (Batson et al., 1987). Immediately after someone confronts an emergency, the integrative processes (behavioral inhibition and emotion regulation) are under the influence of the first system of personal distress; over time, the system related to sympathy mediates these processes (emotion regulation, perspective taking). Together, these processes increase or decrease bystander apathy. For example, although behavioral inhibition and freezing at an early stage can help in assessing and deciding on the situation (McNaughton & Corr, 2004), prolonged inhibition and freezing is ineffective. Likewise, the ability to regulate initial aversive reactions to an emergency, which are tightly linked to dispositional levels of personal distress and sympathy (Eisenberg & Eggum, 2009), is crucial in deciding to help. Taking into account the perspective of other bystanders, as well as the victim, mediated by the core process of sympathy (Eisenberg & Eggum, 2009), can positively influence felt moral responsibility (Paciello, Fida, Cerniglia, Tramontano, & Cole, 2013), the cognitive belief of competence, and ultimately the decision to help (Patil et al., 2017). This cascade of processes in response to an emergency is reflexive at first, whereas the later stages can be described as reflective. This distinction between reflexive and reflective might be dependent on experience, and the coupling of situation and response can be completely reflexive for certain individuals or situations (Rand & Epstein, 2014; Zaki & Mitchell, 2013). As for explaining bystander apathy, however, pluralistic ignorance, evaluation apprehension, and diffusion of responsibility might simply be the summary terms of the attenuated integrative processes of emotion regulation, behavioral inhibition, and perspective taking mediated by the motivational system of personal distress.

Concluding Remarks

This perspective opens up new ways to study the neural and psychological mechanisms of bystander apathy by taking into account situational and dispositional factors. Although ecological validity is a challenge in neuroimaging studies, innovations such as virtual reality, together with neuroimaging and behavioral testing, portable neuroimaging systems, and laboratory-based investigations of people who provided help in real life, will allow the important next steps in bystander research. The bottom-up approach for which we argue sketches a novel perspective on the bystander effect and already paves the way for a different explanation. Together, findings from recent neuroimaging and behavioral studies suggest that the bystander effect is the result of a reflexive action system that is rooted in an evolutionarily conserved mechanism and operates as a function of dispositional personal distress. In the end, we do not actively choose apathy, but are merely reflexively behaving as bystanders.

Recommended Reading

Fischer, P., Krueger, J. I., Greitemeyer, T., Vogrincic, C., Kastenmüller, A., Frey, D., . . . Kainbacher, M. (2011). (See References). A review and meta-analysis of 50 years of research on the bystander effect that provides a critical overview and analysis of factors mitigating bystander apathy.

Hortensius, R., Schutter, D. J. L. G., & de Gelder, B. (2016). (See References). A recent study investigating the influence of a disposition to experience personal distress on bystander apathy by using behavioral and neurophysiological measures.

Preston, S. D. (2013). The origins of altruism in offspring care. Psychological Bulletin, 139, 1305–1341. A comprehensive and important review on how evolutionarily conserved mechanisms related to offspring care can drive a wide variety of altruistic behaviors in humans.

Slater, M., Rovira, A., Southern, R., Swapp, D., Zhang, J. J., Campbell, C., & Levine, M. (2013). Bystander responses to a violent incident in an immersive virtual environment. PLOS ONE, 8(1), Article e52766. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052766. A first demonstration of how virtual reality can be used to systematically address factors mediating the bystander effect that were hitherto impossible to investigate.

Zanon, M., Novembre, G., Zangrando, N., Chittaro, L., & Silani, G. (2014). (See References). An investigation that used a combination of virtual reality and neuroimaging to elucidate the neural mechanisms underlying the occurrence of helping behavior and show the importance of the medial prefrontal cortex in this process.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Huiskes and G. J. Will for insightful discussions that further inspired this work and S. Bell for valuable comments on a version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Action Editor: Randall W. Engle served as action editor for this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared that there were no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship or the publication of this article.

Funding: This work was supported by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for Research 2007–13 (ERC Grant agreement numbers 249858 “Tango” and 295673).

References

- Alexander W. H., Brown J. W. (2011). Medial prefrontal cortex as an action-outcome predictor. Nature Neuroscience, 14, 1338–1344. doi: 10.1038/nn.2921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batson C. D., Fultz J., Schoenrade P. A. (1987). Distress and empathy: Two qualitatively distinct vicarious emotions with different motivational consequences. Journal of Personality, 55, 19–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L. (1971). The effect of another bystander’s ability to help on bystander intervention in an emergency. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 7, 367–379. [Google Scholar]

- Darley J. M., Latané B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8, 377–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N., Eggum N. D. (2009). Empathic responding: Sympathy and personal distress. In Decety J., Ickes W. J. (Eds.), The social neuroscience of empathy (p. 71–84). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Euston D. R., Gruber A. J., McNaughton B. L. (2012). The role of medial prefrontal cortex in memory and decision making. Neuron, 76, 1057–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer P., Krueger J. I., Greitemeyer T., Vogrincic C., Kastenmüller A., Frey D., . . . Kainbacher M. (2011). The bystander-effect: A meta-analytic review on bystander intervention in dangerous and non-dangerous emergencies. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 517–537. doi: 10.1037/a0023304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis K. B., Gummerum M., Ganis G., Howard I. S., Terbeck S. (2018). Virtual morality in the helping professions: Simulated action and resilience. British Journal of Psychology, 109, 442–465. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fultz J., Batson C. D., Fortenbach V. A., McCarthy P. M., Varney L. L. (1986). Social evaluation and the empathy-altruism hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 761–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia S. M., Weaver K., Moskowitz G. B., Darley J. M. (2002). Crowded minds: The implicit bystander effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 843–853. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.83.4.843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano W. G., Habashi M. M. (2010). Motivational processes underlying both prejudice and helping. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14, 313–331. doi: 10.1177/1088868310361239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano W. G., Habashi M. M. (2015). Searching for the prosocial personality. In Schroeder D. A., Graziano W. G. (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of prosocial behavior (pp. 231–255). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harris V. A., Robinson C. E. (1973). Bystander intervention: Group size and victim status. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 2, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hortensius R., de Gelder B. (2014). The neural basis of the bystander effect—The influence of group size on neural activity when witnessing an emergency. NeuroImage, 93(Pt. 1), 53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hortensius R., Neyret S., Slater M., de Gelder B. (2018). The relation between bystanders’ behavioral reactivity to distress and later helping behavior during a violent conflict in virtual reality. PLOS ONE, 13(4), Article e0196074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hortensius R., Schutter D. J. L. G., de Gelder B. (2016). Personal distress and the influence of bystanders on responding to an emergency. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 16, 672–688. doi: 10.3758/s13415-016-0423-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutcherson C. A., Bushong B., Rangel A. (2015). A neurocomputational model of altruistic choice and its implications. Neuron, 87, 451–462. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.06.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latané B., Dabbs J. M., Jr. (1975). Sex, group size and helping in three cities. Sociometry, 38, 180–194. [Google Scholar]

- Latané B., Darley J. M. (1970). The unresponsive bystander: Why doesn’t he help? New York, NY: Appleton Century Crofts. [Google Scholar]

- Latané B., Nida S. (1981). Ten years of research on group size and helping. Psychological Bulletin, 89, 308–324. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.89.2.308 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Markey P. M. (2000). Bystander intervention in computer-mediated communication. Computers in Human Behavior, 16, 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton N., Corr P. J. (2004). A two-dimensional neuropsychology of defense: Fear/anxiety and defensive distance. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 28, 285–305. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll J., Krueger F., Zahn R., Pardini M., de Oliveira-Souza R., Grafman J. (2006). Human fronto-mesolimbic networks guide decisions about charitable donation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 103, 15623–15628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604475103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paciello M., Fida R., Cerniglia L., Tramontano C., Cole E. (2013). High cost helping scenario: The role of empathy, prosocial reasoning and moral disengagement on helping behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 55, 3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.11.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patil I., Zanon M., Novembre G., Zangrando N., Chittaro L., Silani G. (2017). Neuroanatomical basis of concern-based altruism in virtual environment. Neuropsychologia. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plötner M., Over H., Carpenter M., Tomasello M. (2015). Young children show the bystander effect in helping situations. Psychological Science, 26, 499–506. doi: 10.1177/0956797615569579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rameson L. T., Morelli S. A., Lieberman M. D. (2012). The neural correlates of empathy: Experience, automaticity, and prosocial behavior. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 24, 235–245. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand D. G. (2016). Cooperation, fast and slow: Meta-analytic evidence for a theory of social heuristics and self-interested deliberation. Psychological Science, 27, 1192–1206. doi: 10.1177/0956797616654455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand D. G., Epstein Z. G. (2014). Risking your life without a second thought: Intuitive decision-making and extreme altruism. PLOS ONE, 9(10), Article e109687. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rilling J., Gutman D., Zeh T., Pagnoni G., Berns G., Kilts C. (2002). A neural basis for social cooperation. Neuron, 35, 395–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romer D., Gruder C. L., Lizzadro T. (1986). A person–situation approach to altruistic behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1001–1012. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.5.1001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ross A. S., Braband J. (1973). Effect of increased responsibility on bystander intervention: II. The cue value of a blind person. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 25, 254–258. doi: 10.1037/h0033964 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinke C. B. A., Sorger B., Goebel R., de Gelder B. (2010). Tease or threat? Judging social interactions from bodily expressions. NeuroImage, 49, 1717–1727. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenberg S. F., Christ C. C., Carlo G. (2013). Afraid to help: Social anxiety partially mediates the association between 5-HTTLPR triallelic genotype and prosocial behavior. Social Neuroscience, 8, 400–406. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2013.807874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bos K., Müller P. A., van Bussel A. A. L. (2009). Helping to overcome intervention inertia in bystander’s dilemmas: Behavioral disinhibition can improve the greater good. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 873–878. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.03.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Stock J., Hortensius R., Sinke C., Goebel R., de Gelder B. (2015). Personality traits predict brain activation and connectivity when witnessing a violent conflict. Scientific Reports, 5, Article 13779. doi: 10.1038/srep13779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waytz A., Zaki J., Mitchell J. P. (2012). Response of dorsomedial prefrontal cortex predicts altruistic behavior. The Journal of Neuroscience, 32, 7646–7650. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6193-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaki J., Mitchell J. P. (2013). Intuitive prosociality. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22, 466–470. doi: 10.1177/0963721413492764 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zanon M., Novembre G., Zangrando N., Chittaro L., Silani G. (2014). Brain activity and prosocial behavior in a simulated life-threatening situation. NeuroImage, 98, 134–146. doi:10.j.neuroimage.2014.04.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoccola P. M., Green M. C., Karoutsos E., Katona S. M., Sabini J. (2011). The embarrassed bystander: Embarrassability and the inhibition of helping. Personality and Individual Differences, 51, 925–929. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.07.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]