Abstract

Objective

Describe outcomes of open fetal surgery for myelomeningocele (MMC) repair in two Brazilian hospitals and the impact of surgical experience on outcome.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Population

237 pregnant women carrying a fetus with an open spinal defect.

Methods

Surgical details, and maternal and fetal outcomes collected from all patients.

Main outcome measures

Analysis of surgical and perinatal outcome parameters.

Results

Total surgical time was 119 ± 7.6 minutes. Preterm labour occurred in 24.2%, premature rupture of membranes in 26.7%, placental abruption in 0.8%, need for a blood transfusion at delivery in 2.1%, and dehiscence at the repair site in 2.5%. Reversal of hindbrain herniation at birth occurred in 71.4%. There were no maternal deaths or severe maternal morbidities. The failure rate with the patient anaesthetised was 0.42% and perinatal mortality was 2.1% (three intrauterine demises and two neonatal deaths). Comparing results from our study in the first 3 years with the last 3 years demonstrated improvement in the total surgical time (121.2 ± 6.4 versus 118.5 ± 8.2 minutes, P = 0.005) and an increase in reversal of hindbrain herniation at birth (64.0 versus 77.1%, P = 0.042).

Conclusion

Our open fetal surgical approach for MMC was effective and results were comparable to past studies. Improvements in surgical performance and perinatal outcome increased as the surgical team became more familiar with the procedure.

Funding

The study was funded solely by institutional funds.

Tweetable abstract

Brazilian experience of in utero open surgery for myelomeningocele repair.

Keywords: Myelomeningocele, open fetal surgery, perinatal outcome, spina bifida

Short abstract

Tweetable abstract

Brazilian experience of in utero open surgery for myelomeningocele repair.

Introduction

Myelomeningocele (MMC) is a life‐altering birth defect resulting from incomplete closure of the neural tube determined by a complex interaction between genetic and environmental factors during the early stages of fetal development. Each year in the USA, approximately 1500 babies are born with spina bifida,1 a defect associated with morbidities during the lifespan of affected individuals, such as cognitive and respiratory deficiencies, varying degrees of motor deficiencies, skeletal deformities, bladder and fecal incontinence, and hydrocephalus secondary to brainstem herniation by the foramen magnum resulting from obstruction of cerebrospinal fluid flow.2 Despite medical and surgical interventions performed after birth, Chiari II malformation is associated with high personal, family, and social costs, and remains the main cause of death in the first 5 years of life in patients with MMC.3, 4

The justification for performing an intrauterine MMC correction was based on the possibility of preventing or minimising the effects of brain stem herniation and nerve root lesions due to prolonged exposure to amniotic fluid. Indeed, initial nonrandomised studies suggested a significant benefit from prenatal repair of MMC.5, 6, 7

A multicentre, prospective, randomised clinical trial, the Management of Myelomeningocele Study (MOMS), compared fetal surgery with standard neonatal repair and demonstrated that fetal repair led to a decreased rate of shunting at 12 months of age, increased reversal of hindbrain herniation and improved outcomes, including the ability to walk at 30 months of age.8 Based upon the results of this randomised clinical trial, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal‐Fetal Medicine recommended that women with pregnancies complicated by fetal MMC who meet established criteria for intrauterine repair should be counselled in a nondirective fashion regarding all management options, including the possibility of open maternal‐fetal surgery.9

The establishment of an open fetal surgery programme for MMC in Brazil has become a necessity because of the high number of births and the legal limitation against termination of pregnancy. Based on our initial experience we initiated a fetal MMC repair programme soon after publication of the MOMS study.13 However, due to Brazilian administrative limitations against use of the surgical stapler recommended by the MOMS trial, we developed a surgical technique that did not use surgical stapler.14 The present study analyses the results of intrauterine MMC repair on a large cohort performed in two Brazilian hospitals and, in addition, analyses the influence of surgical team experience on patient outcome.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, we review the outcomes of 237 patients selected for open fetal surgery for MMC repair in two hospitals in the city of São Paulo (Hospital e Maternidade Santa Joana and Hospital São Paulo‐EPM/UNIFESP) over a 6‐year period, between 2011 and 2017, performed by the same surgical team using a modified surgical approach described previously.14, 15 All patients gave written informed consent for the procedure and consented to their clinical data being used for research purposes. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Hospital São Paulo and Hospital e Maternidade Santa Joana (April 27, 2016, Reference: CEP 0598). There was no patient or public involvement in this retrospective study, and no specific funding was sought for this study.

The inclusion criteria were: singleton pregnancy; maternal age 18 or more years of age; gestational age at surgery between 24 and 27 weeks; MMC with the upper boundary located between T1 and S1; evidence of hindbrain herniation; normal karyotype and absence of other fetal malformations; body mass index (BMI) <40 kg/m2. The exclusion criteria were: fetal kyphosis >30o, high risk for preterm deliveries (cervix length measurement by transvaginal ultrasound <25 mm and/or history of prematurity in a previous pregnancy); placenta praevia; uterine anomaly (fibroids and Müllerian abnormality); maternal conditions that would constitute an additional risk for maternal health (poorly controlled diabetes and hypertension, HIV, hepatitis B or C positivity); maternal‐fetal Rh/Kell alloimmunisation or history of fetal neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia and maternal psychosocial limitations.

Pregnant women were admitted to both hospitals 1 day before surgery for preanaesthetic evaluation and oral hydration, and were prescribed 10 mg diazepam as pre‐operative medication. After a fasting period of 8 hours the women were conducted to a high complexity surgical ward. Prior to anaesthesia, 2 g of intravenous cephazolin was administered prophylactically. The women were anaesthetised with a combination of general and intradural anaesthesia followed by magnesium sulphate 2 g/hour for tocolysis. The gravid uterus was exposed by an 18‐cm Joel‐Cohen laparotomy and exteriorised under continuous evaluation of fetal well‐being. The fetal position, placenta, and umbilical cord were then scanned using a sterile ultrasonography transducer. If the fetus was in the breech position, cephalic version was required. The site of the longitudinal hysterotomy was chosen according to the placental insertion being performed in the corporal region of the uterus with extension of 4–6 cm.

After the location of the hysterotomy was chosen, two Vycril 0 full‐thickness stay sutures 1 cm apart were placed to keep the amniotic membrane attached to the myometrium and serving as a support point for uterine opening using electrocautery. Four Allis forceps were then placed on the cut edges of the myometrium until the amniotic membrane was exposed. The amniotic membrane was opened under direct visualisation and two De Bakey vascular forceps were placed, and the myometrium and fetal membrane were opened with scalpel and scissor. A repair stitch was positioned at the end of the opening and a full‐thickness Vicryl 0 running suture was placed around the forceps encircling the entire incision. A continuous Monocryl 4‐0 suture was performed around the uterine opening involving the inner portion of the myometrium and the amniotic membrane to prevent membrane separation and premature membrane rupture. Indeed, it was observed that the reparative activity at the suture site of the fetal membrane was characterised by a significant increase in collagen fibres. The findings suggest the occurrence of collagen synthesis, tissue remodelling, and repair of suture site, a mechanism likely to prevent the amniotic fluid leakage.17

The fetus was visualised and positioned by extrauterine manipulation through the uterine wall until the MMC sac was in the centre of the hysterotomy, and an additional fetal analgesia by subcutaneous injection of fentanyl (20 mg/kg of estimated fetal weight) was given. Fetal heart rate (FHR) was monitored during all procedures and we identified a reduction in fetal heart rate mainly during the neurosurgical stage.16 We decided to avoid intramuscular fentanyl for fetal anaesthesia and subsequently no fetal bradycardia was observed during our surgeries.

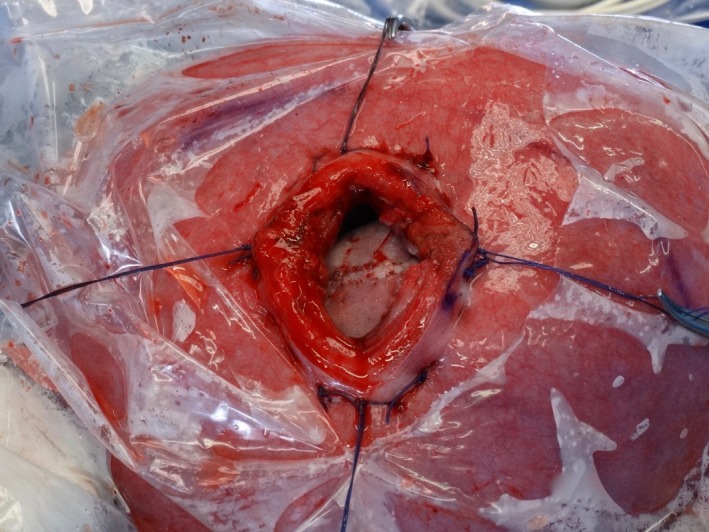

The fetal temperature was monitored during the entire procedure with a digital infrared laser thermometer; the temperature in the operating room was also monitored. To prevent the uterine temperature from falling below 30 °C, the uterine surface was irrigated with a heated saline solution and the uterus was wrapped using a sterile plastic cover (Figure 1), leaving only the region of the hysterotomy exposed. In cases of maternal hypotension, ephedrine or metaraminol were used for preservation of utero‐placental flow. Additionally, in cases of fetal bradycardia, atropine (0.02 mg/kg) and adrenaline (1 μg/kg) was administered to the pregnant women.

Figure 1.

The uterus was wrapped using a sterile plastic cover, leaving only the region of the hysterotomy exposed to perform the neurosurgery.

The MMC was closed in a fashion similar to postnatal closure with the assistance of a Zeiss surgical microscope and/or Zeiss magnifying glass. The most important steps were the release of the cord and the treatment of the tethered spinal cord. Often, we found a fibrotic band fixing the top part of the placode to the dura mater. This ligament was found in more than 90% of cases of MMC and we consider the release of the cord one of the most important steps in the procedure. After reconstruction of the placode to its original form, the dura mater was hermetically closed with polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) 5.0. In most cases, the dura mater firmly adhered to the aponeurosis, tying the two membranes together. The skin was closed by placing a continuous poliglecaprone 25 (Monocryl) 5.0 suture. If the primary closure was not achieved, a suture transposing two skin flaps (zetaplasty) was placed. In all cases, the skin could be closed, and the healing process was effective without the use of exogenous material. 15

The uterine closure was performed in two steps. The first step involves continuous suture of the myometrium with Vicryl 2–0 followed by interrupted suture of the myometrium with Vicryl 0. Before the complete closure of the uterine wall, a silicone urinary catheter number 10 was inserted into the uterine cavity and the uterus was filled with saline solution at 37 °C. The uterus was then put back into the abdominal cavity and the laparotomy closed in a standard fashion.

The patient was transferred to an intensive care unit for the first 24 hours of postoperative care due to the effects of general anaesthesia and magnesium sulphate. The perioperative management involved the use of tocolytics including magnesium sulphate, terbutaline, and nifedipine. The patients were discharged from the hospital when they were ambulatory, eating a regular diet, and had achieved appropriate pain control. In addition to regular prenatal clinical follow up, patients were monitored weekly with transabdominal ultrasonography to assess amniotic fluid index, uterine scar conditions, cerebral ventricular dimension, position of the cerebellum in the posterior fossa, and fetal well‐being.

Each patient was scheduled for elective caesarean delivery at 37 weeks of gestation or earlier in the case of obstetric indications such as preterm labour, premature rupture of membranes, chorioamnionitis, placental abruption, fetal distress, suspected uterine dehiscence or rupture by ultrasound examination with uterine scar thickness <2 mm.

During postoperative follow up, patients were advised to remain at home for up to 30 weeks with access to specialists in maternal‐fetal medicine. Corticosteroids were prescribed for pulmonary maturity and patients were allowed, if they wished, to return to their homes for prenatal care and delivery. When delivery was necessary before 32 weeks, the patients were enrolled in a neuroprotection protocol with magnesium sulphate given at least 4 hours before the caesarean section.

On the day of delivery, laboratory tests of the institutional postpartum haemorrhage protocol were requested. The patients received intradural anaesthesia and the caesarean section was performed through the same skin surgical scar of the fetal surgery. In all procedures, the obstetric team was supplemented by a paediatric neurosurgeon who analysed the clinical condition of the newborn and assessed the surgical scar in the lumbar region.

During the caesarean section, due care was taken during fetal extraction to prevent lumbar scar damage. After removal of the placenta, a detailed evaluation of the conditions of the uterine scar was performed and separate stitches of Vicryl 0 sutures were used; the closure of the caesarean section performed in the usual manner. The criteria for providing a blood transfusion at the time of delivery followed the institutional protocol, taking into consideration the volume of blood loss, maternal haemodynamic conditions, and weight of the surgical sponges.

The data on maternal and fetal characteristics, fetal surgery, delivery conditions, and perinatal outcome were collected prospectively and transferred to an excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA), and analysed using the PASW programme (version 18.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables are reported as mean ± SD and categorical variables as n (%). Maternal and fetal characteristics data such as parity, fetal gender, predominant placental location, lesion level, and type of lesion are presented as percentages. Maternal age and schooling (years) are presented as mean ± SD. Surgical and perinatal characteristics such as gestational age at surgery, total operative time, interval between surgery and delivery, gestational age at delivery, and birthweight are presented as mean ± SD. Maternal pulmonary oedema in the perioperative period, preterm labour, preterm premature rupture of membrane (PPROM), chorioamniotic membrane separation, chorioamnionitis, oligohydramnios, abruptio placentae, uterine scar dehiscence, blood transfusion at delivery, perinatal death, reversal of hindbrain herniation at birth, blood transfusion at delivery, dehiscence of repair site, and perinatal mortality are presented as percentages. To compare our perinatal results from the first 3 years (Group 1) with those from the last 3 years (Group 2), we used Mann–Whitney and Chi‐square tests. Significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

During the study period, 319 pregnant women with a sonographic diagnosis of MMC were screened for the possibility of fetal surgery. After a multidisciplinary evaluation using a protocol similar to the MOMS trial with minor modifications, and parental counselling, 82 of the women (25.7%) were not included in this study for one of the following reasons: gestational age >27 weeks (n = 23), fetal surgery was not authorised by health managers for different reasons (n = 17), the presence of maternal diseases such as chronic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, systemic lupus erythematosus, positive serology for acquired immunodeficiency virus, BMI ≥40 kg/m2 (n = 16), increased risk of preterm delivery or haemorrhage (n = 12), fetal kyphosis or other associated malformations (n = 10), and psychosocial issues (n = 4).

In all, 237 consecutive fetal surgeries were performed; no maternal death or severe maternal morbidity was observed among these women. The perinatal loss rate was 2.1% (three were intrauterine demises: one in the immediate postoperative period because of abruptio placentae, one on postoperative day 29 because of umbilical cord constrictions after chorioamniotic membrane separation, and one on postoperative day 58 after premature rupture of membrane and severe oligohydramnios). One fetal surgery could not be performed due to abruptio placentae as soon as the uterus was displaced out of the abdominal cavity. In this case a longitudinal caesarean section was performed and a liveborn 830‐g baby was delivered and sent to the neonatal intensive care unit. The baby underwent postnatal MMC repair 3 days later after its vital conditions had been stabilised. The rate of failure performing the procedure with the patient anaesthetised in the surgical room was therefore 0.42% (one in 237 surgeries).

Table 1 details the relevant maternal and fetal characteristics of our cohort. The mean ± SD maternal age was 30.9 ± 4.5 years and years of education 14.4 ± 1.7. The percentage of nulliparas (57.2%) was higher than multiparas (42.8%), and 54.2% of the fetuses were male. Placenta location was more frequently in the anterior uterine wall (56.4%). The types of spinal defect were MMC (74.6%) and myeloschisis (25.4%). Spinal dysraphism was located most frequently at L3/L4 (69.5%), followed by L5/S1 (24.6%), and L1/L2 (5.5%). In one woman the upper level of the lesion was located at T11/T12 (only 0.4% of our cohort).

Table 1.

Maternal and fetal characteristics of our cohort. Values are given as mean ± SD or %

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Maternal age, years | 30.9 ± 4.5 |

| Schooling, years | 14.4 ± 1.7 |

| Parity | |

| Nulliparous | 57.2 |

| Multiparous | 42.8 |

| Fetal gender, % | |

| Female | 45.3 |

| Male | 54.7 |

| Predominant placental location | |

| Anterior | 56.4 |

| Posterior | 43.6 |

| Type of lesion | |

| Myeloschisis | 25.4 |

| Myelomeningocele | 74.6 |

| Lesion level | |

| T11/T12 | 0.4 |

| L1/L2 | 5.5 |

| L3/L4 | 69.5 |

| L5/S1 | 24.6 |

Table 2 presents the surgical and perinatal outcomes of our cohort. The mean ± SD gestational age at surgery was 25.2 ± 0.4 weeks, gestational age at birth was 33.6 ± 2.4 weeks, skin‐to‐skin surgery time was 119.7 ± 7.6 minutes, time between fetal surgery and delivery was 52.1 ± 16.7 days, and neonatal birthweight was 2186 ± 506 g. Delivery at less than 30 weeks occurred in 6.8% of subjects, and 47.9% delivered at 35 or more weeks. Chorioamniotic membrane separation was detected by postoperative ultrasonography in 20.8% of cases. Premature rupture of membranes occurred in 26.7% and was related to seven cases of chorioamnionitis (3%). Oligohydramnios was present in 23.3%. Abruptio placentae was diagnosed in two women during fetal surgery and was responsible for one fetal demise and one case of failure to perform fetal surgery. Preterm labour occurred in 24.2% and was associated with all cases of uterine scar dehiscence. Five women required blood transfusion at delivery, associated with uterine atony (n = 3) and uterine rupture (n = 2). Superficial dehiscence of the fetal repair was diagnosed in 2.5% of neonates and required dressing changes during the neonatal period. Hindbrain herniation was reversed in 71.1% according to prenatal ultrasound follow up and was confirmed by neonatal ultrasound and/or magnetic resonance imaging.

Table 2.

Perinatal and surgical outcomes of our cohort

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Total operative time, min | 119.7 ± 7.6 |

| Pulmonary oedema | 2.5 |

| Gestational age at birth, weeks | 33.6 ± 2.4 |

| <30 weeks | 6.8 |

| 30–34 weeks | 45.3 |

| 35–36 weeks | 34.7 |

| ≥37 weeks | 13.1 |

| Birthweight, g | 2186 ± 506 |

| Preterm labour | 24.2 |

| PPROM | 26.7 |

| Chorioamniotic membrane separation | 20.8 |

| Chorioamnionitis | 3.0 |

| Oligohydramnios | 23.3 |

| Abruptio placentae | 0.8 |

| Uterine scar dehiscence | 3.8 |

| Blood transfusion at delivery | 2.1 |

| Dehiscence at repair site | 2.5 |

| Reversal of hindbrain herniation at birth | 71.4 |

| Perinatal mortality | 2.1 |

Surgical outcomes on 236 subjects are reported.

Table 3 presents the comparative surgical and perinatal outcomes between Group 1 (first 3 years, 104 patients) and Group 2 (last 3 years, 132 patients) of this study. There was a significant decrease in the total surgical time (121.2 ± 6.4 versus 118.5 ± 8.2 minutes, P = 0.005), incidence of oligohydramnios (31.7 versus 16.7%, P = 0.010) and increased reversal of hindbrain herniation at birth (64.0 versus 77.1%, P = 0.042) in the second group. Other variables showed an improvement in perinatal outcome but some did not reach statistical significance: pulmonary oedema (3.8 versus 1.5%), gestational age at birth (33.4 ± 2.6 versus 33.7 ± 2.2 weeks), gestational age at birth less than 30 weeks (8.7 versus 5.3%), interval between surgery and delivery (51.6 ± 17.9 versus 52.5 ± 16.5 days), birthweight (2173 ± 533 versus 2195 ± 486 g), preterm labour (27.9 versus 21.2%), PPROM (32.7 versus 22.0%), chorioamniotic membrane separation (26.0 versus 16.7%), chorioamnionitis (5.8 versus 0.8%), dehiscence at repair site (2.9 versus 2.3%), perinatal mortality (3.8 versus 0.8%). There was no need for hysterectomy after delivery in the two groups analysed.

Table 3.

Comparative perinatal outcomes between Group 1 (first 3 years) and Group 2 (last 3 years) of this study

| Group 1 104 | Group 2 132 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total operative time, min | 121.2 ± 6.4 | 118.5 ± 8.2 | 0.005 |

| Pulmonary oedema | 3.8 | 1.5 | 0.476 |

| Gestational age at birth, weeks | 33.4 ± 2.6 | 33.7 ± 2.2 | 0.723 |

| <30 weeks | 8.7 | 5.3 | 0.321 |

| 30–34 weeks | 44.2 | 46.2 | 0.721 |

| 35–36 weeks | 34.6 | 34.8 | 0.970 |

| ≥37 weeks | 12.5 | 13.6 | 0.797 |

| Interval between surgery/delivery, days | 51.6 ± 17.9 | 52.5 ± 16.5 | 0.962 |

| Birthweight, g | 2173 ± 533 | 2195 ± 486 | 0.931 |

| Preterm labour | 27.9 | 21.2 | 0.30 |

| PPROM | 32.7 | 22.0 | 0.089 |

| Chorioamniotic membrane separation | 26.0 | 16.7 | 0.113 |

| Chorioamnionitis | 5.8 | 0.8 | 0.062 |

| Oligohydramnios | 31.7 | 16.7 | 0.010 |

| Abruptio placentae | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.000 |

| Uterine scar dehiscence | 4.8 | 3.0 | 0.715 |

| Blood transfusion at delivery | 1.9 | 2.3 | 1.000 |

| Dehiscence at repair site | 2.9 | 2.3 | 1.000 |

| Reversal of hindbrain herniation at birth | 64.0 | 77.1 | 0.042 |

| Perinatal mortality | 3.8 | 0.8 | 0.238 |

Discussion

Main findings

Our study comprises the largest number of subjects undergoing open fetal surgery for MMC repair. We validated prior reports on the value of this surgical approach compared with post‐delivery intervention. 8, 11, 12, 18 There was more than a 70% reversal of hindbrain herniation. Surgical failure and perinatal mortality rates were extremely low, and there were no maternal deaths or severe maternal morbidities. In agreement with earlier investigations, open fetal surgery was followed by PPROM in almost 27% of our subjects, and 24% experienced preterm labour. The prevalence of placental abruption was only 0.8%. As our surgical team became more experienced with the protocol, outcome parameters improved over time.

Strengths and limitations

This study summarises findings of the largest case series of women who had undergone open fetal surgery for MMC. The surgeries were performed by an integrated multidisciplinary team (including anaesthesiologist, obstetrician, specialist in fetal medicine, paediatric neurosurgeon, intensivist, and neonatologist) in two specialised hospital centres.10 All surgeries were performed by the same team and followed the same protocol, with postoperative follow up and delivery performed by professionals directly involved in the fetal surgery programme. Surgical outcomes and associated clinical variables were similar to prior results in smaller studies. The present study validates the reliability and reproducibility of the reported parameters and can serve as a predictor of what can be expected in subsequent investigations. It also validates that an alternative protocol to the use of stapler for wound closure does not reduce outcome parameters. A limitation of open fetal surgery, as identified in the present and prior studies, is the subsequent high rate of PPROM and preterm labour. Further investigations are needed to pinpoint the variables associated with these events, identify which women are most susceptible to their occurrence, and develop more individualised protocols to reduce their prevalence.

Interpretations

The demographic data, surgical, and perinatal outcomes of our study were similar to results reported in the MOMS study. The average maternal age, schooling, placental location, and fetal gender distribution were similar. The average gestational age at surgery in our cohort was higher than in the MOMS trial (25.2 versus 24.2 weeks). The decision to establish a period between 24 and 27 weeks to perform fetal surgery was due to prenatal care conditions in our country, where fetal anomalies are usually diagnosed between 20 and 24 weeks of gestation and where the patients are referred late to the reference centres in maternal‐fetal medicine. The average surgical time was longer in our study than in MOMS probably because we are not allowed to use staplers in our country and because of the need to perform the suture along the uterine incision to prevent haemorrhage and membrane displacement. However, the results were comparable in terms of pulmonary oedema, gestational age at birth, and perinatal mortality.

Compared with our study, the obstetrical postoperative management of the MOMS trial had more deliveries occurring later than 37 weeks (21.0 versus 13.1%) and a higher mean birthweight (2383 ± 688 versus 2186 ± 506 g). However, the MOMS trial showed an increased risk of preterm labour (38.0 versus 24.2%), premature rupture of membrane (46.0 versus 26.7%), abruptio placentae (6.0 versus 0.8%), uterine scar dehiscence (10.5 versus 3.8%), blood transfusion at delivery (9.0 versus 2.1%), and dehiscence at repair site (13.0 versus 2.5%). The reversal of hindbrain herniation at birth was significantly higher in our study (71.4 versus 36.0%), probably because of experience gained over the time, clearly demonstrated by comparing the outcomes in the first 3 years and in last 3 years of the cohort. There was a significant improvement in the total surgical time and reversal of hindbrain herniation at birth, showing the importance of the learning curve of the medical and hospital staff.

Conclusion

The surgical approach with minor modifications showed similar results compared with the MOMS trial. There were improvements in surgical performance and perinatal outcome as the multidisciplinary team became more familiar and confident with the procedure. However, women should be advised of the risks of this procedure, mainly the risk of PPROM, preterm labour, and future obstetrical limitations.

Disclosure of interests

None declared. Completed disclosure of interests form available to view online as supporting information.

Contribution to authorship

AFM designed the study, analysed the data, wrote the first draft, and corrected the final version of the manuscript. MMB, HJFM, SGS, EFMS, ICS, and PAD contributed to the analysis of the data and collaborated in the editing of the manuscript. SC contributed to the analysis of the data and corrected the final version of the manuscript of the study. All participants were members of the surgical team.

Details of ethics approval

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of Hospital São Paulo – Escola Paulista de Medicina/Federal University of São Paulo‐UNIFESP and Hospital e Maternidade Santa Joana (April 27, 2016, Reference: CEP 0598). All patients gave written informed consent.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Katia Regina de Carvalho and Nelma Bastos Bezerra Rego for updating and organising the database. Marcos Maeda provided the statistical analysis.

Supporting information

Moron AF, Barbosa MM, Milani HJF, Sarmento SG, Santana EFM, Suriano IC, Dastoli PA, Cavalheiro S. Perinatal outcomes after open fetal surgery for myelomeningocele repair: a retrospective cohort study. BJOG 2018; 125:1280–1286.

Linked article This article is commented on by Yves Ville, p. 1287 in this issue. To view this mini commentary visit https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.15311.

References

- 1. Parker SE, Mai CT, Canfield MA, Rickard R, Wang Y, Meyer RE, et al. Updated national birth prevalence estimates for selected birth defects in the United States, 2004–2006. National Birth Defects Prevention Network. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2010;88:1008–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rintoul NE, Sutton LN, Hubbard AM, Cohen B, Melchionni J, Pasquariello PS, et al. A new look at myelomeningoceles: functional level, vertebral level, shunting, and the implications for fetal intervention. Pediatrics 2002;109:409–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Worley G, Schuster JM, Oakes WJ. Survival at 5 years of a cohort of newborn infants with myelomeningocele. Dev Med Child Neurol 1996;38:816–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tennant PW, Pearce MS, Bythell M, Rankin J. 20‐year survival of children born with congenital anomalies: a population‐based study. Lancet 2010;375:649–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Adzick NS, Sutton LN, Crombleholme TM, Flake AW. Successful fetal surgery for spina bifida. Lancet 1998;352:1675–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bruner JP, Tulipan N, Paschall RL, Boehm FH, Walsh WF, Silva SR, et al. Fetal surgery for myelomeningocele and the incidence of shunt‐dependent hydrocephalus. JAMA 1999;282:1819–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Farmer DL, von Koch CS, Peacock WJ, Danielpour M, Gupta N, Lee H, et al. In utero repair of myelomeningocele: experimental pathophysiology, initial clinical experience, and outcomes. Arch Surg 2003;138:872–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Adzick NS, Thom EA, Spong CY, Brock JW 3rd, Burrows PK, Johnson MP, et al. A randomized trial of prenatal versus postnatal repair of myelomeningocele. N Engl J Med 2011;364:993–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Committee Opinion No. 720: Maternal‐Fetal Surgery for Myelomeningocele . Committee on Obstetric Practice, Society for Maternal‐fetal Medicine. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:e164–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cohen AR, Couto J, Cummings JJ, Johnson A, Joseph G, Kaufman BA, et al. MMC Maternal‐Fetal Management Task Force: Position statement on fetal myelomeningocele repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;210:107–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bennett KA, Carroll MA, Shannon CN, Braun SA, Dabrowiak MK, Crum AK, et al. Reducing perinatal complications and preterm delivery for patients undergoing in utero closure of fetal myelomeningocele: further modifications to the multidisciplinary surgical technique. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2014;14:108–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moldenhauer JS, Soni S, Rintoul NE, Spinner SS, Khalek N, Martinez‐Poyer J, et al. Fetal myelomeningocele repair: the post‐MOMS experience at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. Fetal Diagn Ther 2015;37:235–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hisaba WJ, Cavalheiro S, Almodim CG, Borges CP, de Faria TC, Araujo Júnior E, et al. Intrauterine myelomeningocele repair postnatal results and follow‐up at 3.5 years of age – initial experience from a single reference service in Brazil. Childs Nerv Syst 2012;28:461–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moron AF, Barbosa M, Milani H, Hisaba W, Carvalho N, Cavalheiro S. 771: short‐term surgical and clinical outcomes with a novel method for open fetal surgery of myelomeningocele. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212:S374. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cavalheiro S, da Costa MDS, Mendonça JN, Dastoli PA, Suriano IC, Barbosa MM, et al. Antenatal management of fetal neurosurgical diseases. Childs Nerv Syst 2017;33:1125–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Santana EF, Moron AF, Barbosa MM, Milani HJ, Sarmento SG, Araújo E, et al. Fetal heart rate monitoring during intrauterine open surgery for myelomeningocele repair. Fetal Diagn Ther 2016;39:172–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carvalho NS, Moron AF, Menon R, Cavalheiro S, Barbosa MM, Milani HJ, et al. Histological evidence of reparative activity in chorioamniotic membrane following open fetal surgery for myelomeningocele. Exp Ther Med 2017;14:3732–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moldenhauer JS, Adzick NS. Fetal surgery for myelomeningocele: after the Management of Myelomeningocele Study (MOMS). Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2017;22:360–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials