ABSTRACT

Objective

To assess the immediate effects of fetal pulmonary valvuloplasty on right ventricular (RV) size and function as well as in‐utero RV growth and postnatal outcome.

Methods

Patients with pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum (PAIVS) or critical pulmonary stenosis (CPS) who underwent fetal pulmonary valvuloplasty at our center between October 2000 and July 2017 were included. Echocardiographic data obtained before and after the procedure were analyzed retrospectively (median interval after intervention, 1 (range, 1–3) days) for ventricular and valvular dimensions and ratios, RV filling time (duration of tricuspid valve (TV) inflow/cardiac cycle length), TV velocity time integral (TV‐VTI) × heart rate (HR) and tricuspid regurgitation (TR) velocity. Longitudinal data were collected from only those fetuses followed up in our center. Outcome was assessed using the scoring system as described by Roman et al. for non‐biventricular outcome.

Results

Thirty‐five pulmonary valvuloplasties were performed in our institution on 23 fetuses with PAIVS (n = 15) or CPS (n = 8). Median gestational age at intervention was 28 + 4 (range, 23 + 6 to 32 + 1) weeks. No fetal death occurred. Immediately after successful intervention, RV/left ventricular length (RV/LV) ratio (P ≤ 0.0001), TV/mitral valve annular diameter (TV/MV) ratio (P ≤ 0.001), RV filling time (P ≤ 0.00001) and TV‐VTI × HR (P ≤ 0.001) increased significantly and TR velocity (P ≤ 0.001) decreased significantly. In fetuses followed longitudinally to delivery (n = 5), RV/LV and TV/MV ratios improved further or remained constant until birth. Fetuses with unsuccessful intervention (n = 2) became univentricular, all others had either a biventricular (n = 15), one‐and‐a‐half ventricular (n = 3) or still undetermined (n = 3) outcome. Five of nine fetuses with a predicted non‐biventricular outcome, in which the procedure was successful, became biventricular, while two of nine had an undetermined circulation.

Conclusion

In selected fetuses with PAIVS or CPS, in‐utero pulmonary valvuloplasty led immediately to larger RV caused by reduced afterload and increased filling, thus improving the likelihood of biventricular outcome even in fetuses with a predicted non‐biventricular circulation. © 2018 The Authors. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Keywords: congenital heart disease, fetal cardiac intervention, fetal pulmonary valvuloplasty, pulmonary atresia with intact septum

INTRODUCTION

Patients with pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum (PAIVS) or critical pulmonary stenosis (CPS) carry a significant risk of morbidity and mortality1. During fetal life, progression of CPS and development of PAIVS have been reported2, 3. In the absence of high‐grade tricuspid regurgitation (TR) this lesion leads to a hypoplastic right ventricle (RV), which may preclude a biventricular circulation after birth1, 4, 5. Even if biventricular repair can be achieved postnatally, RV function may remain abnormal and the potential of postnatal RV growth is limited6, 7. Therefore, the goal of fetal pulmonary valvuloplasty is to stimulate and promote prenatal RV growth in order to avoid significant RV hypoplasia at birth. It has been shown that the fetal myocardium responds to increased pre‐ and afterload with hyperplasia, in contrast to hypertrophy after birth. Therefore, prenatal treatment could be a unique opportunity to take advantage of a better ventricular growth than that achievable postnatally. A few case reports and small case series have shown that fetal pulmonary valvuloplasty is technically feasible and associated with continued growth of RV structures8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13. The International Fetal Cardiac Intervention Registry reported 16 fetal pulmonary valvuloplasties, of which 11 procedures were successful and resulted in seven liveborn patients, five of which were discharged with a biventricular circulation. However, no data on preprocedure RV dimensions or postprocedure RV growth were recorded in these reports13.

The aim of this study was to assess the immediate effects of fetal pulmonary valvuloplasty on RV size and function as well as in‐utero RV growth and postnatal outcome in fetuses with PAIVS or CPS.

METHODS

All patients who underwent fetal pulmonary valvuloplasty at our center between October 2000 and July 2017 were included in this study. Criteria for fetal pulmonary valvuloplasty were either membranous atresia or a critical stenosis of the pulmonary valve (PV) with a recognizable RV outflow tract (RV‐OT), retrograde flow in the ductus arteriosus and a hypoplastic hypertrophic RV with suprasystemic pressures as assessed by the velocity of the TR jet. Exclusion criteria were muscular atresia of the RV‐OT, severe TR with low velocity (< 2.5 m/s) or the presence of large RV sinusoids. The study was approved by our local ethics committee (study number K‐104‐16) and informed consent was not required.

All patients had an echocardiographic examination (Vivid 7®, Vivid E9®, Vivid E95®; GE Medical Systems, Zipf, Austria) a few days before and after the procedure (median interval after intervention, 1 (range, 1–3) days) by the same experienced echocardiographer (G.T.). Two‐dimensional and Doppler echocardiographic data were recorded and stored on video tape (prior to 2010) or in digital format (Echopac®, GE Medical Systems). Echocardiographic data were analyzed retrospectively for ventricular and valvular dimensions and ratios, as well as for RV filling time (duration of tricuspid valve (TV) inflow/cardiac cycle length), TV velocity time integral (TV‐VTI) × heart rate (HR), and TR velocity.

All interventions were performed under ultrasound guidance as described previously8, 14 and under general anesthesia of the mother without separate fetal analgesia. The fetal RV was punctured with a 16‐, 18‐ or 19‐gauge needle (Cook® Medical Systems, Limerick, Ireland). A 3‐, 5‐ or 4‐mm coronary balloon catheter (Maverick®, Boston Scientific, Vienna, Austria) was used for valve dilatation. The balloon‐to‐valve ratio was aimed at between 1 and 1.5; however, balloon size was limited by the inner diameter of the needle. Eight patients had two and two patients had three procedures due to technical failure of the first attempts. A procedure was considered successful if the PV was perforated and/or passed and dilated with a balloon catheter. A partially successful procedure was defined as one in which the PV was perforated and passed, but the valve was not dilated with the full diameter of the balloon.

Patients' charts were reviewed for postnatal procedures and outcome. Biventricular outcome was defined as a circulation in which the RV was the only source of pulmonary blood flow in the absence of any signs of right‐heart failure. Undetermined circulation was one in which a modified Blalock–Taussig (BT) shunt or ductal stent was placed postnatally and the final circulation was still unclear. Eight patients were delivered and treated in our center, whereas all other patients were delivered and managed in their respective home countries. For the longitudinal assessment of RV growth, only measurements from fetuses that were delivered and followed up at our center were used.

To assess the effect of fetal pulmonary valvuloplasty on outcome, patients were grouped retrospectively according to the scoring system published by Roman et al.15. This scoring system is based on four parameters (TV/mitral valve annular diameter (TV/MV) ratio < 0.7, RV/left ventricle length (RV/LV) ratio < 0.6, RV filling time < 31.5% of cardiac cycle length and presence of RV sinusoids), with 100% sensitivity and 75% specificity predicting a non‐biventricular outcome if three of these four criteria are fulfilled. High‐quality data were available for 20/23 patients: 10 patients had a score of three, four had a score of two, two a score of one and four patients had a score of zero.

Significant changes in RV function and dimensions before and after intervention were evaluated using paired t‐tests. Statistical significance was considered as P ≤ 0.05. Fetal cardiac Z‐scores were obtained using a statistical program (Cardio Z; UBQO, Evelina Children's Hospital, London, UK). Data are expressed as median with range, unless stated otherwise.

RESULTS

Between October 2000 and July 2017, a total of 129 fetal intracardiac interventions were performed in 108 patients at our center. Of these, 35 procedures were fetal pulmonary valvuloplasties which were carried out on 23 fetuses with PAIVS (n = 15) or CPS (n = 8). Most interventions (31/35) took place after January 2010. Median gestational age at the time of intervention was 28 + 4 (range, 23 + 6 to 32 + 1) weeks. Patients were referred from nine different countries. Baseline echocardiographic measurements of the patients are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Cardiac measurements, before intervention, of 23 fetuses with pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum or critical pulmonary stenosis, that underwent fetal pulmonary valvuloplasty

| Parameter | n * | Value (median (range)) |

|---|---|---|

| RV/LV ratio | 19 | 0.57 (0.47 to 0.70) |

| TV/MV ratio | 19 | 0.69 (0.62 to 0.97) |

| RV filling time† | 19 | 0.28 (0.19 to 0.42) |

| RV length Z‐score | 18 | –2.95 (–4.64 to –1.33) |

| TV annular diameter Z‐score | 18 | –1.77 (–3.52 to 0.39) |

| TR Vmax (m/s) | 19 | 4.83 (3.28 to 5.5) |

| TV‐VTI × HR (cm × bpm) | 18 | 821.5 (287.5 to 1859) |

Data not available in all cases.

Duration of tricuspid valve (TV) inflow indexed to cardiac cycle length.

HR, heart rate; RV, right ventricular; RV/LV ratio, right to left ventricular length ratio; TR Vmax, maximum velocity of tricuspid regurgitation; TV/MV ratio, tricuspid to mitral valve annular diameter ratio; TV‐VTI, tricuspid valve velocity time integral.

Seventeen patients had a technically successful and four a partially successful procedure (91.3%). The procedure itself was successful in 22/35 (62.9%) interventions. Individual patient data regarding cardiac anatomy and procedural details, complications and outcome are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Procedure details, complications and outcome of fetal pulmonary valvuloplasty (FPV) performed on 23 fetuses with pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum (PAIVS) or critical pulmonary stenosis (CPS)

| Case | Cardiac anatomy | GA at FPV (weeks) | Year of FPV | FPV attempts (n) | GA at subsequent FPV(s) (weeks) | Technical success | Balloon/valve ratio | Pericardial effusion n.t. | Bradycardia n.t. | Prediction score* before FPV | PV gradient (Vmax) after FPV (m/s) | GA at birth (weeks) | Postnatal procedure(s) | Circulation | Follow‐up (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1† | PAIVS | 27 + 6 | 2000 | 1 | — | Y | 1.0 | N | Y | 3 | ND | 37 + 6 | PV dilatation, modified BT shunt, BT shunt removal at 9 months | BV | 16.36 |

| 2 | CPS | 24 + 0 | 2003 | 1 | — | N | — | N | N | ND | — | 32 + 0 | Modified BT shunt | UV | NND |

| 3† | PAIVS | 32 + 1 | 2007 | 2 | 31 + 2 | Y | ND | N | N | ND | ND | 37 + 1 | PV dilatation, modified BT shunt, BDG and RVOT enlargement | 1.5 V | 9.28 |

| 4 | CPS | 28 + 5 | 2010 | 1 | — | Y | 1.0 | N | N | 3 | 3.1 | 40 + 3 | PV dilatation, RVOT patch, PV valvotomy and modified BT shunt, coiling BT shunt | BV | 7.16 |

| 5 | CPS | 29 + 3 | 2010 | 1 | — | Y | 1.0 | N | N | 0 | 4.4 | 38 + 3 | PV dilatation | BV | 6.82 |

| 6† | PAIVS | 25 + 0 | 2012 | 1 | — | Y | 1.1 | N | N | 3 | 1.3 | 37 + 1 | Valvotomy and modified BT shunt, coiling BT shunt | BV | 4.78 |

| 7 | PAIVS | 31 + 0 | 2013 | 1 | — | N | — | N | N | 3 | — | ND | Modified BT shunt followed by BDG anastomosis and Fontan procedure | UV | LFU |

| 8 | CPS | 26 + 6 | 2013 | 2 | 25 + 4 | Partial | 1.0 | N | N | 3 | 2.1 | 35 + 1 | Modified BT shunt, PV dilatation, BDG and RPA patch | 1.5 V | 3.56 |

| 9 | PAIVS | 25 + 5 | 2014 | 1 | — | Y | 0.9 | N | N | 3 | 3.5 | 40 + 4 | PV dilatation (4×) | BV | 2.40 |

| 10 | PAIVS | 28 + 5 | 2014 | 1 | — | Y | 1.1 | Y | Y | 2 | 2.1 | 37 + 5 | PV dilatation | BV | 2.75 |

| 11† | CPS | 29 + 3 | 2015 | 1 | — | Y | 0.9 | Y | N | 0 | 2.2 | 39 + 1 | PV dilatation | BV | 1.81 |

| 12 | PAIVS | 27 + 5 | 2015 | 2 | 27 + 0 | Y | 0.8 | N | Y | 3 | 3.3 | 39 + 1 | Radiofrequency perforation PV, modified BT shunt, PV dilatation | Undetermined | 1.61 |

| 13† | PAIVS | 23 + 6 | 2015 | 3 | 23 + 5, 28 + 5 | Partial | 0.6 | N | Y | 3 | 1.2 | 38 + 2 | PV perforation and dilatation, modified BT shunt and RVPAC, BDG and RVPAC | 1.5 V | 1.63 |

| 14 | CPS | 25 + 1 | 2015 | 2 | 26 + 2 | Partial | 0.9 | N | Y | 0 | 3.4 | 38 + 3 | PV dilatation | BV | 1.64 |

| 15 | PAIVS | 30 + 4 | 2016 | 2 | 30 + 1 | Y | 0.7 | Y | Y | 2 | 2.9 | 38 + 1 | PV dilatation (2×) | BV | 1.25 |

| 16 | PAIVS | 28 + 3 | 2016 | 2 | 26 + 4 | Y | 1.1 | Y | Y | 2 | ND | 38 + 4 | PV perforation and dilatation, PDA stent, PV dilatation (2×), spontaneous closure of PDA stent, PV dilatation | BV | 1.13 |

| 17 | PAIVS | 27 + 3 | 2016 | 1 | — | Y | 1.2 | N | N | 2 | 3.7 | 38 + 0 | PV dilatation (2×) | BV | 0.90 |

| 18† | CPS | 30 + 1 | 2016 | 1 | — | Y | 0.8 | N | N | 1 | 1.3 | 33 + 5 | PV dilatation (2×) | BV | 0.93 |

| 19† | PAIVS | 27 + 4 | 2016 | 3 | 22 + 3, 26 + 4 | Partial | 0.8 | N | N | 3 | 4.0 | 39 + 3 | PV perforation and dilatation, PDA stent and PV dilatation | BV | 0.78 |

| 20 | PAIVS | 28 + 4 | 2016 | 2 | 28 + 3 | Y | ND | N | Y | ND | ND | 39 + 1 | Modified BT shunt and RVOT enlargement | Undetermined | 0.22 |

| 21† | PAIVS | 29 + 1 | 2017 | 1 | — | Y | 1.1 | N | N | 1 | 2.8 | 30 + 4 | No intervention | BV | 0.1 NND |

| 22 | CPS | 28 + 3 | 2017 | 1 | — | Y | ND | N | Y | 0 | 1.6 | 35 + 5 | PV dilatation | BV | 0.24 |

| 23 | PAIVS | 29 + 5 | 2017 | 2 | 29 + 0 | Y | 1.0 | N | N | 3 | 3.5 | 30 + 1 | On i.v. prostaglandins at last follow‐up | Undetermined | 0.11 |

Assessed by four‐point scoring system of Roman et al.15 (criteria: tricuspid/mitral valve annular diameter ratio < 0.7, RV/LV length ratio < 0.6, RV filling time < 31.5% of cardiac cycle length, presence of RV sinusoids) indicating non‐BV circulation after birth for fetuses with score of 3 with 100% sensitivity and 75% specificity.

Patient followed up and treated at our institution. 1.5 V, one‐and‐a‐half ventricle circulation; BDG, bidirectional Glenn anastomosis; BT shunt, Blalock–Taussig shunt; BV, biventricular; GA, gestational age; i.v., intravenous; LFU, lost to follow‐up; LV, left ventricle; N, no; ND, no data available; NND, neonatal death; n.t., necessitating treatment; PDA, persistent ductus arteriosus; PV, pulmonary valve; RPA, right pulmonary artery; RV, right ventricle; RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract; RVPAC, right ventricle‐to‐pulmonary artery conduit; TV, tricuspid valve; UV, univentricular; Y, yes.

Mortality, complications and prematurity

No fetal death occurred. All 23 fetuses were liveborn at a median gestational age of 38 + 2 (range, 30 + 1 to 40 + 4) weeks. Pericardial effusion necessitating treatment occurred in 4/35 (11.4%) and persistent bradycardia in 11/35 (31.4%) procedures.

There were six (26.1%) preterm deliveries, two due to premature rupture of membranes (3 days after intervention at 30 + 2 weeks and 8 weeks after intervention at 33 weeks), one after 3 weeks of intervention due to pre‐eclampsia of the mother and three due to preterm labor between 9 days and 8 + 2 weeks after procedure. Additionally, one neonate was found to have CHARGE syndrome with esophageal atresia.

Immediate changes after fetal pulmonary valvuloplasty

For the 17 fetuses that had successful pulmonary valvuloplasty, all cardiac parameters improved significantly after the intervention (Figure 1); the most significant change was observed for RV filling time. Cardiac measurements before and after successful intervention are shown in Table 3. Figure 2 shows change in RV dimensions and improvement of RV filling time with change from a short monophasic to a longer biphasic inflow and Figures 3a and b illustrate decrease of TR velocity after intervention. Even after a successful intervention, there remained a gradient across the PV in almost all cases (Table 2). Figure 3c shows the residual PV gradient with a new pulmonary regurgitation immediately after a successful procedure. Fetuses with a partially successful intervention (n = 4) demonstrated improvement in cardiac parameters as well, but not in all parameters (Table S1).

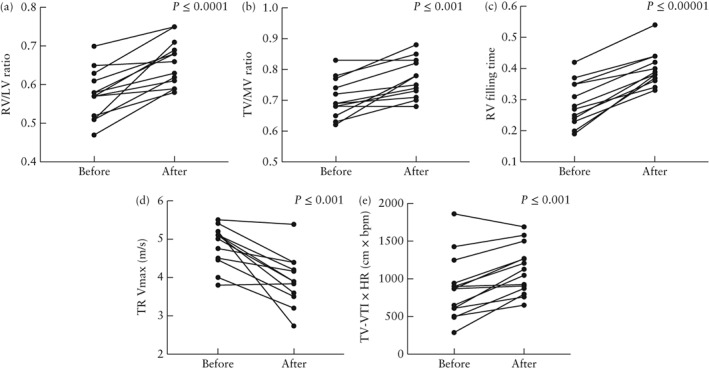

Figure 1.

Cardiac measurements before and after completely or partially successful fetal pulmonary valve intervention in 21 fetuses with pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum or critical pulmonary stenosis. Patients 6 and 23 were excluded from (c) and (e) due to exclusive retrograde filling of right ventricle by severe pulmonary regurgitation. HR, heart rate; RV/LV ratio, right to left ventricular length ratio; TR Vmax, maximum velocity of tricuspid regurgitation; TV/MV ratio, tricuspid to mitral valve annular diameter ratio; TV‐VTI, tricuspid valve velocity time integral.

Table 3.

Cardiac measurements before and after completely successful intervention in 17 fetuses that underwent fetal pulmonary valvuloplasty for pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum or critical pulmonary stenosis

| Parameter | n * | Value (median (range)) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before intervention | After intervention | |||

| RV/LV ratio | 14 | 0.57 (0.47 to 0.70) | 0.64 (0.58 to 0.75) | 0.0001 |

| TV/MV ratio | 13 | 0.69 (0.62 to 0.83) | 0.78 (0.68 to 0.88) | 0.0004 |

| RV filling time† | 13 | 0.28 (0.19 to 0.42) | 0.38 (0.33 to 0.54) | 0.000002 |

| RV length Z‐score | 13 | –2.95 (–4.64 to –1.33) | –2.08 (–3.85 to –1.09) | 0.0005 |

| TV annular diameter Z‐score | 13 | –1.81 (–3.52 to –1.31) | –1.56 (–2.55 to –0.53) | 0.0012 |

| TR Vmax | 12 | 4.88 (3.28 to 5.50) | 3.90 (2.74 to 5.38) | 0.0008 |

|

TV‐VTI × HR (cm × bpm) |

11 | 868 (287.5 to 1859) | 1044 (650 to 1687.5) | 0.008 |

Data not available in all cases.

Duration of tricuspid valve (TV) inflow indexed to cardiac cycle length.

HR, heart rate; RV, right ventricular; RV/LV ratio, right to left ventricular length ratio; TR Vmax, maximum velocity of tricuspid regurgitation; TV/MV ratio, tricuspid to mitral valve annular diameter ratio; TV‐VTI, tricuspid valve velocity time integral.

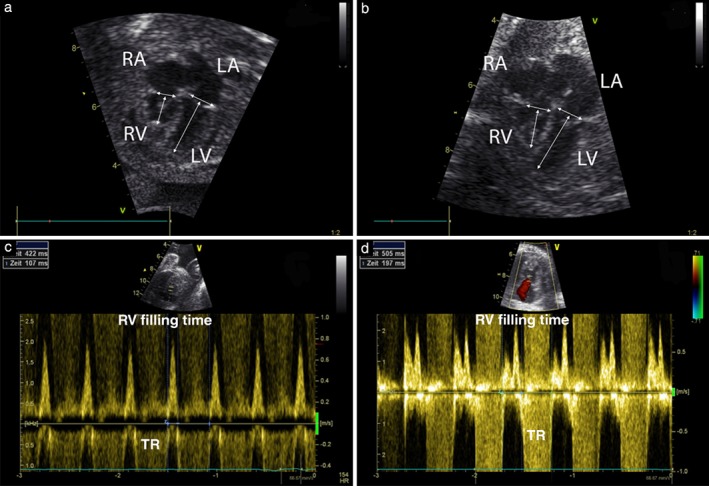

Figure 2.

Apical four‐chamber views of Patient 9 before (a) and 2 days after (b) intervention; arrows mark points of measurement for tricuspid and mitral valve annular diameter and right (RV) and left (LV) ventricular length; note increase in RV length and tricuspid valve diameter after intervention. Pulsed‐wave Doppler traces with RV filling times of Patient 15 before (c) and after (d) intervention; note change from short monophasic RV filling of 25% (107/422 ms) of cardiac cycle length before intervention to longer biphasic RV filling of 39% (197/505 ms) of cardiac cycle length after intervention. LA, left atrium; RA, right atrium; TR, tricuspid regurgitation.

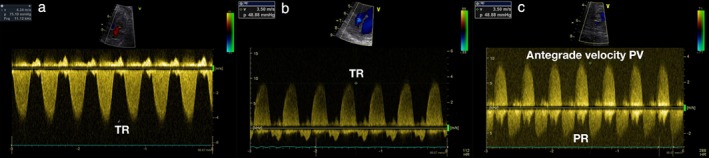

Figure 3.

Continuous‐wave (CW) Doppler traces of tricuspid regurgitation (TR) in Patient 11 before and after intervention; pressure gradient was reduced from 75 mmHg (4.34 m/s) (a) to 49 mmHg (3.50 m/s) (b). (c) CW Doppler tracing of blood flow across pulmonary valve (PV) with remaining antegrade gradient of 49 mmHg and new pulmonary regurgitation (PR) in Patient 9 after intervention (c).

Intrauterine course

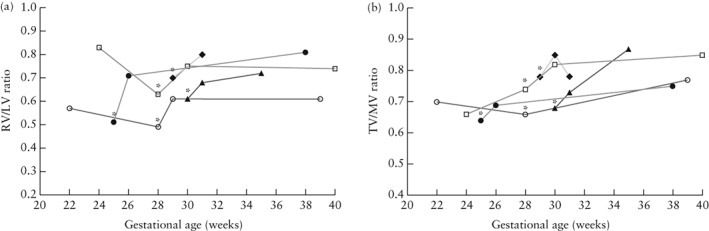

Longitudinal data of cases with successful or partially successful intervention were available from five patients who were all delivered and followed up in our institution. Preintervention, immediate postintervention and first postpartum measurements are shown in Figure 4. The greatest change in RV/LV ratio occurred immediately after the procedure and it continued to increase in three patients, whereas it remained stable in the other two patients. TV/MV ratio after intervention continued to increase in four patients.

Figure 4.

Longitudinal development of right to left ventricular length (RV/LV) ratio (a) and tricuspid to mitral valve annular diameter (TV/MV) ratio (b) in five fetuses that underwent fetal pulmonary valvuloplasty. Plotted are measurements before intervention, immediately after intervention and immediately postpartum, with intervention indicated by asterisks. In Patients 11 and 19, two measurements were performed before intervention. Measurement of TV/MV ratio immediately after intervention is missing for Patient 19 (b).  , Patient 6;

, Patient 6;  , Patient 11;

, Patient 11;  , Patient 18;

, Patient 18;  , Patient 19;

, Patient 19;  , Patient 21.

, Patient 21.

Progressive PV stenosis during advancing gestation was observed in almost all fetuses and re‐atresia occurred in four patients. Two of those fetuses had a successful intervention at 27 + 5 and 28 + 3 weeks with a balloon‐to‐valve ratio of 0.8 and 1.1, respectively. The remaining two had partially successful interventions at 23 + 6 and 27 + 4 weeks with balloon‐to‐valve ratios of 0.6 and 0.8, respectively.

Postnatal outcome

Postnatal procedures and outcome at last follow‐up for all patients are listed in Table 2. There were two neonatal deaths, both of which occurred after a preterm delivery. Patient 2 was delivered at 32 weeks following an unsuccessful intervention, and was diagnosed with CHARGE syndrome and died after placement of a BT shunt due to hemodynamic instability. Patient 21 was delivered at 30 + 4 weeks, 9 days after a successful intervention, and was found to have a good sized RV with wide open PV; the arterial duct remained open without prostaglandins and the patient rapidly developed severe necrotizing enterocolitis and died after extensive bowel resection.

All other patients were alive after a median follow‐up of 1.63 (range, 0.10–16.36) years. Freedom from mortality after 1 year was 90.2%. Out of the 21 fetuses with a successful or partially successful procedure, with various prediction scores, 15 (71.4%) became biventricular, three (14.3%) had a one‐and‐a‐half ventricle circulation and three (14.3%) had an undetermined circulation. One infant was still on prostaglandins 6 weeks after a preterm birth at 31 weeks and two patients had a modified BT shunt at the age of 2.6 and 19.3 months. All but one of the neonates needed an early PV intervention and 11 additionally required a systemic‐to‐pulmonary‐artery shunt or a ductal stent in the neonatal period.

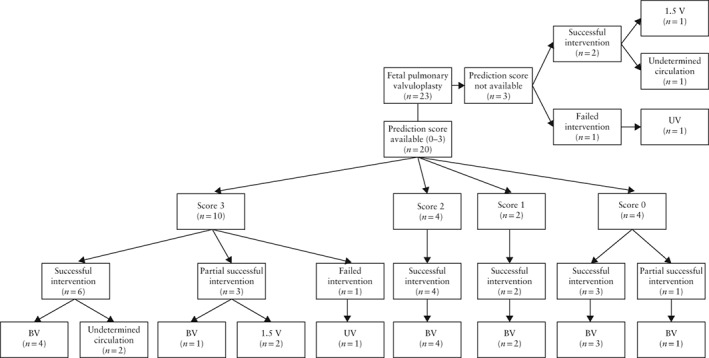

Fetuses with predicted non‐biventricular outcome

The prediction score as described by Roman et al.15 could be calculated for 20 of 23 fetuses (Figure 5). Of these, 10 (50%) had a score of three, which is considered to predict a non‐biventricular circulation after birth with 100% sensitivity. Six of these 10 patients had a successful intervention, four of which achieved a biventricular circulation and two had an undetermined circulation at the age of 41 days and 1.6 years.

Figure 5.

Circulation outcome in 23 fetuses that underwent fetal pulmonary valvuloplasty according to prediction score by Roman et al.15, a four‐point scoring system indicating non‐biventricular (BV) circulation after birth for fetuses with score of 3, with 100% sensitivity and 75% specificity. Note that 5/10 patients with predicted non‐BV outcome had BV circulation. 1.5 V, one‐and‐a‐half ventricle circulation; UV, univentricular circulation.

DISCUSSION

In the absence of major coronary fistulae or muscular atresia of the RV outflow tract, RV and TV size at birth are the major determinants for a biventricular outcome. We have shown that technically successful pulmonary valvuloplasty in second‐ and third‐trimester fetuses with PAIVS or CPS leads to an immediate and significant increase in RV and TV size, decrease in RV pressure and longer and better RV filling. In the five fetuses that were followed up in our institution, we observed that initial cardiac changes were followed by continued growth of RV structures until birth. In more than half of the fetuses with a predicted non‐biventricular outcome and successful procedure, a two‐ventricle circulation was achieved.

In all fetuses with a successful PV intervention, significantly greater RV length and TV diameter were observed 1 to 2 days after the procedure, which has not been described before. We do not believe that real RV or TV growth had occurred in such a short period of time, but we suggest that the decompression of the RV led immediately to improved filling, evidenced by the significantly increased TV‐VTI × HR product, resulting in greater RV volumes. Obviously, RV length had been underestimated before the intervention, because the RV apex was formed by the moderator band. Increased filling after intervention revealed some cavity at the RV apex, which was not visible before. The increase of TV diameter can be explained by better and longer TV opening, which made it easier to measure the full diameter of the valve. This is an important finding, because underestimation of the true RV and TV size may lead to prediction of a poorer outcome resulting in overly pessimistic counseling of the parents. Reduction in RV pressure was also highly significant, as estimated by TR velocity and the lengthening of RV filling time, both logical consequences of establishing and improving forward flow through the PV. Despite being lower than preintervention, RV pressure remained above normal in most cases. We were not able to eliminate completely the gradient across the pulmonary outflow tract, particularly in late gestation, mainly because the available balloons were too small due to the limited inner diameter of the needles we used. In fact, we think that a balloon‐to‐valve ratio of 1.3–1.5 is necessary to perform an optimal pulmonary valvuloplasty. Even when we considered the intervention as only partially successful, immediate improvements could be observed, indicating that even a minor RV decompression is able to improve hemodynamics.

No procedure‐related deaths or intrauterine deaths occurred at our center. Certainly, right heart interventions are better tolerated than are left heart ones, and a key advantage was that all procedures were carried out by an experienced team that had already performed a substantial number of left heart interventions16, 17.

An important question of this study was whether the initial increase in RV size would be followed by natural growth of right heart structures. It has been shown in animal experiments that the fetal myocardium responds with myocyte proliferation, i.e. hyperplasia, to increased pre‐ and afterload18, 19, 20. The ability for myocyte proliferation is lost shortly after birth and the postnatal myocardium responds with hypertrophy rather than hyperplasia. After neonatal pulmonary valvuloplasty, the RV will grow but only in relation to body size and catch‐up growth does not occur7. Our limited longitudinal data provide evidence that, after a period of little or no RV growth, a successful PV intervention could have the potential to restore RV growth towards term, a finding that is in agreement with observations in previous small studies8, 10, 11. Three out of five fetuses in our cohort even demonstrated a further increase in RV/LV ratio and four of five patients a further increase in TV/MV ratio, indicating that there could even be an additional catch‐up growth of the RV prenatally. We speculate that this RV growth is achieved by myocardial hyperplasia, which would not have been possible after birth. Theoretically, at birth, these RVs should consist of more myocardial cells with a potential for better postnatal adaptation and improved long‐term function.

During advancing gestation, progressive gradients across the PV were observed in almost all fetuses. This could have been due to real re‐stenosis of the dilated PV or related to progressive better RV filling and thus increased flow across the valve (relative stenosis). Re‐atresia of the PV was observed in four fetuses. Two fetuses had only partially successful interventions early in gestation, so the created opening of the PV was obviously too small to stay open until birth. Interestingly, the two other fetuses initially had successful interventions and also developed atresia. It is possible that the balloon‐to‐valve ratios of 0.8 and 1.1 were still too small and this could have been avoided with larger balloons.

In the absence of a valid control group during the same study period, we chose to refer to published criteria for prediction of outcome. Several reports have been published regarding the prediction of a non‐biventricular/univentricular outcome in fetuses with PAIVS/CPS5, 11, 15, 21. Using the criteria published by Roman et al.15, we found that more than half of the patients with a predicted non‐biventricular outcome could achieve a biventricular circulation. This provides evidence that a timely in‐utero pulmonary valvuloplasty is able to modify the natural history of fetuses with PAIVS or CPS and increases the likelihood of biventricular circulation after birth. However, as normal RV size could not be achieved even after a successful procedure, it is justified to avoid delaying intervention until the RV becomes severely hypoplastic, and instead perform fetal pulmonary valvuloplasty as soon as possible to allow optimal in‐utero recovery.

The most important limitations of this study are its retrospective design, the small number of patients and the non‐standardized postnatal management of the respective referral centers. A further limitation is the lack of a control group of matched fetuses that did not undergo fetal pulmonary valvuloplasty; data published by Roman et al.15 were used instead. Furthermore, reliable longitudinal data were available for only five out of 23 patients; therefore, no significance of continuous RV growth could be calculated, and certainly a greater number of patients would be needed to confirm these observations.

In conclusion, for selected fetuses with PAIVS or CPS, in‐utero pulmonary valvuloplasty leads immediately to larger RV caused by reduced afterload and increased filling, thus improving the likelihood of a biventricular outcome.

Supporting information

Table S1 Cardiac measurements of four fetuses before and after partially successful fetal pulmonary valvuloplasty

REFERENCES

- 1. Dyamenahalli U, McCrindle BW, McDonald C, Trivedi KR, Smallhorn JF, Benson LN, Coles J, Williams WG, Freedom RM. Pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum: management of, and outcomes for, a cohort of 210 consecutive patients. Cardiol Young 2004; 14: 299–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rice MJ, McDonald RW, Reller MD. Progressive pulmonary stenosis in the fetus: two case reports. Am J Perinatol 1993; 10: 424–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Todros T, Presbitero P, Gaglioti P, Demarie D. Pulmonary stenosis with intact ventricular septum: documentation of development of the lesion echocardiographically during fetal life. Int J Cardiol 1988; 19: 355–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Daubeney PE, Sharland GK, Cook AC, Keeton BR, Anderson RH, Webber SA. Pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum: impact of fetal echocardiography on incidence at birth and postnatal outcome. UK and Eire Collaborative Study of Pulmonary Atresia with Intact Ventricular Septum. Circulation 1998; 98: 562–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Salvin JW, McElhinney DB, Colan SD, Gauvreau K, del Nido PJ, Jenkins KJ, Lock JE, Tworetzky W. Fetal tricuspid valve size and growth as predictors of outcome in pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum. Pediatrics 2006; 118: e415–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mishima A, Asano M, Sasaki S, Yamamoto S, Saito T, Ukai T, Suzuki Y, Manabe T. Long‐term outcome for right heart function after biventricular repair of pulmonary atresia and intact ventricular septum. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2000; 48: 145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ovaert C, Qureshi SA, Rosenthal E, Baker EJ, Tynan M. Growth of the right ventricle after successful transcatheter pulmonary valvotomy in neonates and infants with pulmonary atresia and intact ventricular septum. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1998; 115: 1055–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tulzer G, Arzt W, Franklin RCG, Loughna PV, Mair R, Gardiner HM. Fetal pulmonary valvuloplasty for critical pulmonary stenosis or atresia with intact septum. Lancet 2002; 360: 1567–1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Galindo A, Gutiérrez‐Larraya F, Velasco JM, de la Fuente P. Pulmonary balloon valvuloplasty in a fetus with critical pulmonary stenosis/atresia with intact ventricular septum and heart failure. Fetal Diagn Ther 2006; 21: 100–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tworetzky W, McElhinney DB, Marx GR, Benson CB, Brusseau R, Morash D, Wilkins‐Haug LE, Lock JE, Marshall AC. In utero valvuloplasty for pulmonary atresia with hypoplastic right ventricle: techniques and outcomes. Pediatric. 2009; 124: e510–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gómez Montes E, Herraiz I, Mendoza A, Galindo A. Fetal intervention in right outflow tract obstructive disease: selection of candidates and results. Cardiol Res Pract 2012; 2012: 592403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pedra SF, Peralta CF, Pedra CAC. Future Directions of Fetal Interventions in Congenital Heart Disease. Interv Cardiol Clin 2013; 2: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moon‐Grady AJ, Morris SA, Belfort M, Chmait R, Dangel J, Devlieger R, Emery S, Frommelt M, Galindo A, Gelehrter S, Gembruch U, Grinenco S, Habli M, Herberg U, Jaeggi E, Kilby M, Kontopoulos E, Marantz P, Miller O, Otano L, Pedra C, Pedra S, Pruetz J, Quintero R, Ryan G, Sharland G, Simpson J, Vlastos E, Tworetzky W, Wilkins‐Haug L, Oepkes D. International Fetal Cardiac Intervention Registry: A Worldwide Collaborative Description and Preliminary Outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 66: 388–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wohlmuth C, Tulzer G, Arzt W, Gitter R, Wertaschnigg D. Maternal aspects of fetal cardiac intervention. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2014; 44: 532–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roman KS, Fouron J‐C, Nii M, Smallhorn JF, Chaturvedi R, Jaeggi ET. Determinants of outcome in fetal pulmonary valve stenosis or atresia with intact ventricular septum. Am J Cardiol 2007; 99: 699–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Arzt W, Wertaschnigg D, Veit I, Klement F, Gitter R, Tulzer G. Intrauterine aortic valvuloplasty in fetuses with critical aortic stenosis: experience and results of 24 procedures. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011; 37: 689–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wohlmuth C, Wertaschnigg D, Wieser I, Arzt W, Tulzer G. Tissue Doppler imaging in fetuses with aortic stenosis and evolving hypoplastic left heart syndrome before and after fetal aortic valvuloplasty. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016; 47: 608–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Clark EB, Hu N, Frommelt P, Vandekieft GK, Dummett JL, Tomanek RJ. Effect of increased pressure on ventricular growth in stage 21 chick embryos. Am J Physiol 1989; 257: H55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Saiki Y, Konig A, Waddell J, Rebeyka IM. Hemodynamic alteration by fetal surgery accelerates myocyte proliferation in fetal guinea pig hearts. Surgery 1997; 122: 412–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. deAlmeida A, McQuinn T, Sedmera D. Increased ventricular preload is compensated by myocyte proliferation in normal and hypoplastic fetal chick left ventricle. Circ Res 2007; 100: 1363–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gardiner HM, Belmar C, Tulzer G, Barlow A, Pasquini L, Carvalho JS, Daubeney PE, Riggy ML, Gordon F, Kulinskaya E, Franklin RC. Morphologic and functional predictors of eventual circulation in the fetus with pulmonary atresia or critical pulmonary stenosis with intact septum. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 51: 1299–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Cardiac measurements of four fetuses before and after partially successful fetal pulmonary valvuloplasty