Abstract

We evaluated health-related quality of life (QoL) in HIV infection participants with virologic failure (VF) on first-line antiretroviral therapy (ART) in 9 resource-limited settings (RLS). ACTG SF-21 was completed by 512 participants at A5273 study entry; 8 domains assessed: general health perceptions (GHP), physical functioning (PF), role functioning (RF), social functioning (SF), cognitive functioning (CF), pain (P), mental health (MH), and energy/fatigue (E/F); each was scored between 0 (worst) to 100 (best). Mean QoL scores ranged from 67 (GHP) to 91 (PF, SF, CF). QoL varied by country; high VL and low CD4 were associated with worse QoL in most domains, except RF (VL only), SF (CD4 only) and CF (neither). Number of comorbidities, BMI and history of AIDS were associated with some domains. Relationships between QoL and VL varied among countries for all domains. The association of worse disease status with worse QoL may reflect low QoL when ART was initiated and/or deterioration associated with VF.

Keywords: health-related quality of life, HIV, virologic failure, antiretroviral therapy, resource-limited settings

Introduction

Long-term complications of HIV infection and its treatment, as well as quality of life (QoL), are important considerations for HIV-infected individuals. This is because antiretroviral therapy (ART) has dramatically changed the course of the HIV/AIDS epidemic by reducing morbidity and mortality (1). Once a terminal disease, HIV infection is now considered a chronic medical condition, with individuals on effective ART having life expectancies similar to the general population (2).

QoL is a multidimensional concept and can be influenced by many factors such as income, housing, social support, and life situation. Health-related QoL is a dimension of broader QoL that reflects the impact of disease and treatment on a person’s ability to carry out daily activities and affects well-being, taking into account the biological and psychological effects. QoL measurements are important to access a person’s perception of his/her own health (3, 4).

QoL measures were introduced in the early 1990s for HIV infection in resource-rich settings (5), and used to evaluate factors associated with QoL as well as effects of ART on QoL (6–8). Poorer immunological status, HIV-related symptoms, depression, lack of social support, unemployment and low adherence to ART were most frequently and consistently reported to be associated with worse QoL in these settings (9).

QoL at initiation of first-line ART in resource-limited settings (RLS) has varied with disease severity, demographics and country (3, 10, 11) and improves over time after starting ART (10–12). However, it is possible that individuals failing first-line ART may have decreased QoL. This has immediate relevance to the individual affected and may also be associated with lower levels of adherence to treatment (13) and so could lead to poorer outcomes on subsequent treatments. This topic is understudied in RLS. The aim of this study was therefore to evaluate QoL in HIV-infected participants experiencing virologic failure (VF) on first-line ART in 9 RLS.

Methods

Study design

We conducted an exploratory analysis of QoL data collected from participants enrolling in the AIDS Clinical Trial Group (ACTG) A5273 study, entitled “Multicenter Study of Options for SEcond-Line Effective Combination Therapy (SELECT)”. This study was a phase III, open-label, randomized clinical trial comparing two second-line ART regimens among HIV-infected individuals failing non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI)-containing first-line ART (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov NCT01352715). Details of the study design have been previously described (14). The study was undertaken at 15 sites in 9 countries: Brazil, India (3 sites), Kenya, Malawi (2 sites), Peru (2 sites), South Africa (3 sites), Tanzania, Thailand and Zimbabwe. Participants were enrolled between March-2012 and October-2013 having been on first-line ART for a median of 4.2 years. The study was approved by the institutional review board at each participating site and written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Study participants

Eligible participants were HIV-infected men and women (≥18 years) who had VF confirmed by two consecutive plasma HIV-1 RNA viral load (VL) ≥1000 copies/mL at least one week apart after at least 24 weeks on an NNRTI-containing regimen, which was the preferred first-line ART in many settings and the one recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) at the time of study design and during the course of the study (15). The definition of VF is similar to that suggested by the WHO (16). Resistance tests at first-line VF were not required for entry and it was only available for 4% of participants.

Other inclusion criteria included Karnofsky performance score ≥70, no prior treatment with a protease inhibitor, no history of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection or current HBV infection, and no current active tuberculosis. There was no inclusion criterion regarding CD4 cell count.

Procedures

Health-related quality of life

Participants were interviewed at study entry (before second-line ART initiation) using a modified version of the SF-21 measure (ACTG SF-21) (3, 17). The ACTG SF-21 tool was originally adapted from the Medical Outcomes Study HIV Health Survey (MOS-HIV), an instrument with well-established reliability and validity (18). SF-21 and its short and long forms (SF-12, SF-36) have been widely used in HIV/AIDS research (3, 19–23). Questions formed 8 domains: General Health Perceptions (GHP), Physical Functioning (PF), Role Functioning (RF), Social Functioning (SF), Cognitive Functioning (CF), Pain (P), Mental Health (MH), and Energy/Fatigue (E/F) (Table 1). A standardized score ranging from 0 (worst QoL) to 100 (best QoL) was calculated for each domain using standard methods (3). The ACTG SF-21 tool was administered in a face-to-face interview by study staff in the participant’s local language.

Table 1.

Information obtained using the Short Form 21-item (SF-21) Quality of Life (QoL) Questionnaire

| Domains | Number of items | Summary of contents |

|---|---|---|

| General Health Perceptions (GHP) | 3 | Participants rate their general health, resistance to illnesses, and health outlook. It has been validated by Davies and Ware (38) and Stewart and Ware (39). Two questions are reverse coded to control for response set effects. |

| Physical Functioning (PF) | 4 | It inquired about physical limitations ranging from severe to minor, including lifting heavy objects or running, walking uphill or climbing a few flights of stairs, and being able to eat, dress, bathe and use the toilet by oneself. |

| Role Functioning (RF) | 2 | Participants are asked if their health negatively impacts their ability to perform at a job/school or to work around the house in the past 4 weeks. |

| Social Functioning (SF) | 2 | Participants are asked to what extent their health in the past 4 weeks has limited their social activities (40); one item is reverse coded to control for response set effects. |

| Cognitive Functioning (CF) | 3 | This domain measures the degree of difficulty participants have experienced in the past four weeks with respect to their cognitive abilities. It assesses a participant’s level of difficulty with reasoning/solving problems, being attentive, and remembering. |

| Pain (P) | 2 | This domain assess intensity of physical pain (e.g., headache, muscle pain, back pain, stomach ache) and degree of interference with daily activities in the past four weeks (41); one item is reverse coded to control for response set effects. |

| Mental health (MH) | 3 | This domain assesses anxiety, depression, and overall psychological wellbeing in the past 4 weeks (42). One item is reverse coded to control for response set effects. |

| Energy/ Fatigue (E/F) |

2 | This domain assesses vitality (feeling tired or fatigued and energy to do things the person wanted to); one item is reverse coded to control for response set effects. |

Demographic and Clinical Factors

The following demographic and clinical factors from study entry were included in the analyses: sex, age (years), plasma HIV-1 RNA viral load (VL), CD4 count (CD4), body mass index (BMI), country of enrollment (country), history of AIDS-defining events (history of AIDS), number of comorbidities, and years on first-line ART. History of AIDS was defined by a specified subset of diagnoses codes maintained by the ACTG (Appendix 60) (24) taking into account the WHO (25) and CDC (26) classifications of AIDS-defining events. Number of comorbidities was defined as number of diagnoses (other than AIDS-defining diagnoses) included in ACTG Appendix 60 (considering all ongoing and previous comorbidities).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Univariable linear regression was used to evaluate associations between scores for each QoL domain and, demographic and clinical variables. Continuous variables were initially categorized as: age into <30, 30–39, 40–49 or ≥50 years; VL into <10,000, 10,000–99,999 or ≥100,000 copies/mL; CD4 into <50, 50–199, 200–349 or ≥350 cells/mm3; BMI into <18 (underweight), 18-<25 (normal), 25-<30 (overweight) or ≥30 (obese) kg/m2; number of comorbidities into 0, 1, 2 or ≥3; years on first-line ART <4, 4-<7, ≥ 7 years. Associations of VL, CD4 and country with QoL scores were found for most QoL domains and so were included in multivariable linear regression models for all domains. We then identified other variables that were also associated with QoL, adjusting for VL, CD4 and country, using backwards variable selection, restricting consideration to variables that were statistically significant at p≤0.10 in univariable analysis. The statistical significance threshold for retaining a variable in the model was set at p<0.05 (adjusting for CD4, VL and country). We have also tried forwards selection starting with VL, CD4 and country forced into the model and the same variables were retained. Adding other variables into the final models did not result in any further significant predictor variables. There was no evidence of multi-collinearity and no violation of the regression model assumptions by inspection of plots of residuals versus predicted values. The possibility of different associations of VL and CD4 with QoL domains among countries was evaluated by including interaction terms in the final multivariable models identified by backwards variable selection.

Results

Five hundred and fifteen participants were enrolled in this study; three were excluded from this analysis: two were not on an NNRTI-containing first-line regimen for 24 weeks and one was found to be HBV surface antigen positive (Table 2). Median age was 39 years (inter-quartile range [IQR]: 34–44), approximately half were women and approximately two-thirds were of black race. Median CD4 count was 135 cells/mm3, VL 33,360 copies/mL and BMI 22 kg/m2. A total of 150 participants (29%) had a history of AIDS. Median duration of first-line ART was 4.2 years (IQR:2.3–6.2) and only 36(7.0%) participants had been on first-line ART for <1 year.

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Study Participants at the Time of Quality of Life Assessment at Virologic Failure

| Characteristic | Total (N=512) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 252 (49%) |

| Female | 260 (51%) |

| Age | |

| Median (IQR) | 39 (34; 44) |

| 18–29 | 51 (10%) |

| 30–39 | 227 (44%) |

| 40–49 | 178 (35%) |

| 50+ | 56 (11%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Black | 330 (64%) |

| Non-black | 182 (36%) |

| Country | |

| Brazil | 12 (2%) |

| India | 158 (31%) |

| Kenya | 48 (9%) |

| Malawi | 111 (22%) |

| Peru | 9 (2%) |

| South Africa | 103 (20%) |

| Tanzania | 17 (3%) |

| Thailand | 7 (1%) |

| Zimbabwe | 47 (9%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |

| Median (IQR) | 22 (19; 26) |

| Underweight (<18) | 55 (11%) |

| Normal (18–24) | 295 (58%) |

| Overweight (25–29) | 110 (21%) |

| Obese (≥30) | 52 (10%) |

| VL (HIV-1 RNA copies/mL) | n=510 |

| Median (IQR) | 33,360 (8,033; 138,153) |

| <10,000 | 145 (29%) |

| 10,000–100,000 | 206 (40%) |

| >100,000 | 159 (31%) |

| CD4 (cell counts/mm³) | n=507 |

| Median (IQR) | 135 (53; 271) |

| <50 | 122 (24%) |

| 50–199 | 194 (38%) |

| 200–349 | 121 (24%) |

| ≥350 | 70 (14%) |

| History of AIDS | |

| Yes | 150 (29%) |

| No | 362 (71%) |

| Number of comorbidities | |

| 0 | 180 (35%) |

| 1 | 148 (29%) |

| 2 | 80 (16%) |

| ≥3 | 104 (20%) |

| Time on 1st-line ART (years) | |

| Median (IQR) | 4.2 (2.3; 6.2) |

| <4 | 245 (48%) |

| 4-<7 | 177 (34%) |

| ≥7 | 90 (18%) |

Mean QoL score varied from 67 for the GHP domain through to 91 for the PF, SF and CF domains (Table 3). In univariable analysis, higher VL, lower CD4, lower BMI, higher number of comorbidities, were significantly associated with lower QoL score in most domains (p<0.05). QoL scores varied significantly among countries for all domains. Time on first-line ART was significantly associated with QoL score for several domains but the pattern of mean scores by time on ART differed among domains. Specifically, for PF and RF, mean QoL scores were higher among participants with shorter durations of treatment (i.e. <4 years versus 4-<7 or ≥7 years); whereas for SF, CF and Pain (P), participants with intermediate durations of treatment (i.e. 4-<7 years) had lower QoL scores than participants with shorter (<4 years) or longer (≥7 years) durations. History of AIDS was only associated with (lower) E/F score (p=0.009); and male sex was only associated with (lower) RF score (p=0.020). No associations were observed for alcohol and drug use (data not shown).

Table 3.

Mean (standard deviation) QoL scores overall by demographic and clinical characteristics (univariable analysis) of Study Participants at Virologic Failure

| General Health Perceptions (GHP) | Physical Functioning (PF) | Role Functioning (RF) | Social Functioning (SF) | Cognitive Functioning (CF) | Pain (P) |

Mental Health (MH) | Energy / Fatigue (E/F) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 67 (21) | 91 (17) | 80 (30) | 91 (16) | 91 (16) | 83 (22) | 85 (15) | 80 (20) |

| Country | p<.001 | p<.001 | p<.001 | p<.001 | p<.001 | p<.001 | p<.001 | p<.001 |

| Brazil | 67 (32) | 84 (28) | 90 (17) | 89 (25) | 88 (17) | 84 (31) | 76 (23) | 74 (28) |

| India | 71 (15) | 86 (22) | 56 (33) | 87 (14) | 90 (13) | 76 (21) | 84 (11) | 81 (13) |

| Kenya | 72 (13) | 95 (13) | 96 (12) | 96 (11) | 95 (16) | 93 (13) | 89 (13) | 84 (16) |

| Malawi | 50 (24) | 91 (17) | 83 (28) | 86 (20) | 85 (20) | 76 (25) | 80 (20) | 69 (26) |

| Peru | 67 (23) | 90 (20) | 89 (22) | 89 (18) | 79 (34) | 91 (13) | 71 (21) | 66 (24) |

| South Africa | 74 (17) | 98 (8) | 98 (9) | 98 (10) | 98 (5) | 93 (16) | 90 (13) | 86 (17) |

| Tanzania | 82 (16) | 94 (13) | 90 (20) | 93 (18) | 85 (24) | 85 (26) | 86 (19) | 80 (20) |

| Thailand | 70 (15) | 98 (5) | 93 (19) | 97 (5) | 93 (12) | 92 (11) | 90 (10) | 93 (8) |

| Zimbabwe | 67 (20) | 95 (12) | 92 (18) | 98 (8) | 94 (9) | 86 (18) | 89 (12) | 86 (15) |

| Sex | p=0.223 | p=0.440 | p=0.020 | p=0.433 | p=0.806 | p=0.704 | p=0.062 | p=0.074 |

| Female | 66 (21) | 93 (14) | 84 (27) | 92 (16) | 91 (15) | 83 (21) | 86 (16) | 81 (21) |

| Male | 68 (20) | 90 (20) | 77 (32) | 91 (16) | 91 (16) | 83 (22) | 84 (15) | 79 (19) |

| HIV-1 RNA (copies/mL) | p<.001 | p<.001 | p<.001 | p=0.002 | p=0.033 | p<.001 | p=0.004 | p<.001 |

| <10,000 | 72 (18) | 94 (14) | 86 (27) | 94 (11) | 93 (13) | 87 (18) | 86 (14) | 84 (17) |

| 10,000–100,000 | 69 (18) | 94 (14) | 83 (28) | 92 (15) | 91 (16) | 85 (21) | 86 (14) | 81 (19) |

| >100,000 | 60 (24) | 86 (22) | 72 (33) | 87 (19) | 88 (17) | 77 (24) | 82 (16) | 75 (22) |

| CD4 (cells/mm3) | p<.001 | p=0.006 | p=0.393 | p=0.074 | p=0.030 | p=0.023 | p=0.002 | p=0.002 |

| <50 | 55 (24) | 87 (21) | 80 (28) | 86 (22) | 88 (18) | 78 (26) | 80 (18) | 72 (24) |

| 50–199 | 68 (19) | 91 (20) | 81 (30) | 93 (13) | 92 (15) | 84 (20) | 87 (14) | 81 (19) |

| 200–349 | 73 (16) | 96 (8) | 82 (29) | 93 (12) | 93 (16) | 87 (19) | 87 (14) | 83 (16) |

| ≥350 | 73 (17) | 93 (11) | 75 (33) | 93 (10) | 92 (12) | 81 (20) | 85 (12) | 83 (16) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | p<.001 | p<.001 | p<.001 | p<.001 | p<.001 | p<.001 | p=0.002 | p<.001 |

| <18 | 59 (24) | 80 (24) | 63 (31) | 82 (22) | 85 (18) | 71 (26) | 80 (16) | 72 (23) |

| 18–24 | 66 (21) | 91 (18) | 81 (29) | 91 (16) | 90 (16) | 83 (22) | 85 (15) | 79 (19) |

| 25–29 | 72 (16) | 96 (9) | 87 (27) | 95 (10) | 94 (13) | 87 (19) | 86 (14) | 83 (18) |

| ≥30 | 74 (16) | 95 (11) | 84 (31) | 95 (12) | 95 (10) | 87 (18) | 89 (13) | 85 (20) |

| History of AIDS | p=0.356 | p=0.068 | p=0.901 | p=0.931 | p=0.592 | p=0.568 | p=0.291 | p=0.009 |

| No | 68 (19) | 93 (14) | 80 (30) | 92 (15) | 91 (16) | 83 (22) | 85 (15) | 82 (18) |

| Yes | 65 (23) | 87 (24) | 81 (28) | 90 (18) | 91 (16) | 84 (22) | 84 (16) | 75 (23) |

| Number of comorbidities | p=0.002 | p<.001 | p<.001 | p<.001 | p=0.457 | p<.001 | p=0.081 | p=0.100 |

| 0 | 71 (19) | 93 (17) | 87 (24) | 94 (14) | 92 (16) | 87 (19) | 87 (14) | 82 (19) |

| 1 | 65 (23) | 91 (20) | 83 (29) | 91 (16) | 90 (17) | 85 (21) | 83 (17) | 78 (21) |

| 2 | 64 (22) | 93 (13) | 78 (32) | 91 (16) | 90 (17) | 81 (23) | 84 (15) | 80 (21) |

| ≥3 | 65 (18) | 88 (17) | 67 (33) | 87 (17) | 92 (12) | 74 (23) | 85 (15) | 79 (18) |

| Time on first-line ART (years) | p=0.188 | p=0.003 | p<.001 | p=0.007 | p=0.043 | p=0.001 | p=0.857 | p=0.143 |

| <4 | 69 (19) | 94 (13) | 86 (25) | 93 (14) | 93 (14) | 86 (21) | 85 (15) | 82 (18) |

| 4-<7 | 64 (22) | 90 (19) | 75 (33) | 88 (17) | 89 (18) | 78 (23) | 84 (16) | 78 (21) |

| ≥7 | 67 (21) | 88 (22) | 76 (31) | 92 (15) | 91 (15) | 85 (20) | 85 (16) | 78 (22) |

p-value: t-test from univariable linear regression model; ART: antiretroviral therapy; BMI: body mass index.

Visual inspection of the associations of QoL score with VL across the domains suggested that the major difference in mean QoL was generally between participants with VL >100,000 versus ≤100,000 copies/mL and so for simplicity this categorization was used in multivariable modeling. For similar reasons, CD4 was categorized as <50 versus ≥50 cells/mm3, BMI as <18 versus ≥18 kg/m2, and number of comorbidities as ≥3 versus <3. Table 4 summarizes results from the multivariable models for associations of QoL with VL, CD4 and other variables that were selected for inclusion, adjusted for country (which remained significantly associated with QoL score for all domains; p<.0001). Higher VL was associated with lower QoL score for all domains, except SF and CF. Lower CD4 was associated with lower QoL score for all domains, except RF and CF. After adjusting for country, VL and CD4, few other variables were significantly associated with QoL score: lower BMI was associated with lower PF and lower SF scores; history of AIDS was associated with lower PF and lower E/F scores; and higher number of comorbidities was associated with lower RF and P scores.

Table 4.

Adjusted difference in mean QoL score by VL, CD4, BMI, history of AIDS and number of comorbidities (95% Confidence Interval). All differences are adjusted for the other variables shown and also for country.

| Parameter | General Health Perceptions (GHP) | Physical Functioning (PF) | Role Functioning (RF) | Social Functioning (SF) | Cognitive Functioning (CF) | Pain (P) | Mental Health (MH) | Energy / Fatigue (E/F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VL (copies/ml) >100K vs. ≤100K |

−7.9(−11.5; −4.4) p<.001 |

−4.4(−7.7; −1.1) p=0.010 |

−6.5(−11.5; −1.5) p=0.011 |

−2.1(−5.1; 0.8) p=0.158 |

−2.7(−5.7; 0.3) p=0.080 |

−4.3(−8.4; −0.2) p=0.037 |

−2.9(−5.8; −0.0) p=0.047 |

−5.1(−8.8; −1.5) p=0.006 |

| CD4 (cells/mm3) <50 vs. ≥50 |

−9.4(−13.3; −5.4) p<.001 | −4.3(−8.0; −0.6) p=0.023 |

−3.9(−9.3; 1.6) p=0.163 |

−6.6(−9.9; −3.4) p<.001 |

−2.7(−6.1; 0.6) p=0.111 |

−4.9(−9.4; −0.4) p=0.033 |

−5.7(−8.9; −2.5) p=0.001 |

−5.6(−9.7; −1.5) p=0.007 |

| BMI (kg/m2) <18 vs. ≥18 |

* | −6.8(−11.6; −1.9) p=0.006 |

* | −5.7(−9.9; −1.4) p=0.009 |

* | * | * | * |

| History of AIDS Yes vs. No |

* | −4.7(−8.0; −1.4) p=0.005 |

* | * | * | * | *- | −6.0(−9.6; −2.4) p=0.001 |

| Number of comorbidities ≥3 vs. <3 |

* | * | −7.2(−13.1; −1.3) p=0.016 |

* | * | −9.7(−14.5; −4.9) p<.001 |

* | * |

Not included in the multivariable model chosen by backwards variable selection (see Methods).

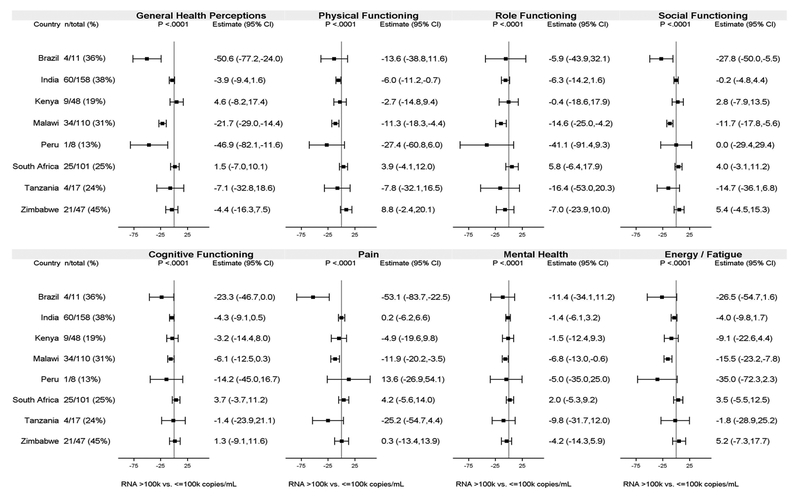

Associations between QoL and VL varied among countries for all domains (interaction p<.0001; Figure 1). The strongest associations were seen in Malawi with statistically significantly lower mean scores among participants with high VL (>100,000 copies/mL) versus lower VL (≤100,000 copies/mL) in all domains. In contrast, there was little of evidence of an association in countries such as India and South Africa which, like Malawi, had enrollment numbers of over 100 and similar proportions of participants with high VL. There was no notable evidence of variability among countries in the association between QoL and CD4 (the only interaction p-value <0.05 was for the Pain domain [interaction p=0.02]).

Figure 1.

Adjusted difference in mean QoL score for participants with HIV-1 RNA >100,000 vs. ≤100,000 copies/mL by country. All differences are adjusted for the variables shown in Table 4 and also for country.

Note: Adjusted differences in mean QoL scores were not estimated for Thailand (as there were no participants with HIV-1 RNA>100,000 copies/mL). “n/total” shows number of participants with HIV-1 RNA>100,000 copies/mL and total number of participants. Bars are 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the adjusted mean difference in QoL score.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating health-related QoL in an HIV-infected population failing first-line ART in RLS. Worse QoL scores at failure of first-line ART were associated with worse disease status as measured by higher VL and lower CD4. This might reflect poorer QoL when ART was initiated and/or its deterioration following treatment failure. However, our study is cross-sectional and so we cannot conclude that poorer QoL is a consequence of poorer HIV disease status at virologic failure as measured by high VL and low CD4. It is possible that the reverse is true: for example, poorer QoL during treatment might contribute to lower levels of treatment adherence leading to worse HIV disease status (13).

Associations of lower QoL scores with worse HIV disease status as measured by lower CD4 and higher VL have been previously observed in studies evaluating HIV-infected individuals initiating first-line ART in the era prior to availability of highly active ART (HAART) (21) and in the HAART era (27) in resource-rich settings, and in a cross-sectional study conducted in several RLS (3). This association was also observed in cross-sectional studies among individuals while taking ART in Uganda and Malawi (28, 29). Our study therefore shows similar cross-sectional associations in individuals failing first-line ART in RLS.

The highly significant heterogeneity in mean QoL scores among countries for all domains, even after adjustment for participants’ disease status, may be related to different cultural perceptions of QoL. It could also be affected by differences in characteristics of participants being enrolled in different countries beyond those characteristics that we had data for (e.g. socio-economic status, social support). Lower quality of life in Malawi for most domains was also observed among clinical trial participants from diverse RLS starting first-line ART (3).

For most QoL domains, we found significantly lower mean QoL score among participants with higher VL versus participants with lower VL, even after adjustment for the extent of immunosuppression as measured by CD4, though there was evidence that this association varied among countries. During the majority of study enrollment time, VL monitoring was not emphasized in RLS by the WHO in favor of providing antiretroviral drugs (15) although the availability of VL monitoring varied widely in different countries. Therefore, it is possible that in some settings, participants, particularly those with higher VL, had been on failing first-line ART for an extended period of time. Although this finding warrants further exploration in settings where VL monitoring might capture virologic failure and adherence issues more quickly, it does however raise a possible concern that non-suppressive ART might lead to deterioration in QoL. Alternatively, our finding that the association of QoL score with VL varied among countries may reflect differences in participant characteristics among countries as discussed above or differences in health perceptions.

Individuals with low BMI (<18 kg/m2) classified as underweight had lower mean QoL scores for the PF and SF domains only. Most (60%) of the participants with the lowest BMI were from India where undernutrition was previously reported to be related to low QoL among HIV-infected individuals (30). Association of low BMI and lower QoL score was also observed for individuals starting first-line ART in Ethiopia (31). Being underweight in some cultures can be related to low social status or illness. The fear of stigma and shame associated with HIV infection may also compromise an individual’s social functioning (32, 33). The PF domain is strongly related to day-to-day activities (e.g. eating, bathing, and lifting heavy objects) and lower scores may reflect frailty related to low BMI.

Our finding of an association between history of AIDS and lower PF and E/F scores may be explained by an ongoing loss of vitality caused by more advanced disease. Symptomatic HIV-infected individuals have poorer QoL than HIV non-infected or asymptomatic HIV-infected individuals (30, 31, 34). Studies conducted in the pre-HAART era observed that individuals with AIDS had worse PF than those with other chronic diseases (epilepsy, gastroesophageal reflux disease, clinically localized prostate cancer, clinical depression, diabetes) (17, 35). In contrast, a cross-sectional study conducted in London found no association of fatigue with more advanced HIV disease or ART use, but a strong association with psychological factors (36). A study in the US found that more advanced HIV disease stage was a significant predictor of lower physical health (27). The variability of these findings in different settings supports a need to study these issues in multiple settings/countries.

In a similar way, our findings of significant associations of lower RF and P scores with higher number of comorbidities might reflect the burden of comorbidities beyond HIV infection on an individual’s daily activities and resultant increased pain. Chronic diseases were strong independent risk factors for low QoL in a study conducted in Tanzania with HIV-infected individuals on ART for at least 2 years (37). This is consistent with our findings although the definition of comorbidities in our study was broader, including not only chronic diseases.

In general, the high mean QoL score in most domains may reflect the profile of study participants enrolled. People entering the study were relatively young (most between 30–50 years) and did not have advanced HIV disease; these characteristics could be reflected in their QoL perception. Individuals with low Karnofsky performance score, HBV infection, active tuberculosis, active drug/alcohol dependence or other conditions that might interfere with study participation, as well as serious illness requiring recent systemic treatment and/or hospitalization were excluded from this study. This may also explain the absence of an association of QoL scores with age.

Compared with other domains, the mean QoL score for the general health perceptions domain was somewhat lower. The GHP domain includes items such as “My health is excellent”, “I have been feeling bad lately” and “In general, would you say your health is (…)”. Even though a participant may be in excellent health, their perception of their health may be poorer due to their HIV status. In the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study in the US, individuals with advanced disease had worse QoL scores than HIV-negative men in all domains. For individuals with CD4 counts above 500 cells/mm3 only GHP was lower (20). Additionally, in a study conducted in Denmark, well-treated HIV-infected individuals with viral suppression and a few comorbidities reported lower scores than HIV-negative participants (34).

This study has limitations. Data were not collected on factors such as employment and educational status, depression or mental health disorders, sexual behavior and social stigma that might be associated with QoL. The population studied was from a clinical trial and so may differ from those in clinical practice. Each clinical site may have selected participants for enrollment differently, with potential differences between countries and between sites. First-line ART VF was identified at study entry and it is possible that participants may have had unidentified virologic failure for an extended period of time, particularly in locations where viral load testing was not part of routine care. It is also possible, therefore, that some HIV-infected people experiencing unidentified virologic failure might die or be lost from care and so not be represented in our study versus a study that was identifying virologic failure proximal to its time of occurrence. Caution should therefore be taken before generalizing our findings to other clinical and cultural settings.

In conclusion, mean QoL scores among individuals failing first-line ART varied among countries in all domains, and were poorer among participants with higher VL and lower CD4 in most domains. Optimization of QoL is particularly important now that treated HIV infection is a chronic disease and individuals have long-term survival and expectations for near-normal life expectancy. Our findings support the need for ongoing effective ART with successful virologic suppression and immunologic recovery, to support possible improvements in QoL. Further investigation of QoL after second-line ART initiation should be considered. This study provides important data for RLS, where individuals may start or switch ART later than in resource-rich settings.

References

- 1).Lima VD, Hogg RS, Harrigan PR, et al. Continued improvement in survival among HIV-infected individuals with newer forms of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2007;21(6):685–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Wandeler G, Johnson LF, Egger M. Trends in life expectancy of HIV-positive adults on antiretroviral therapy across the globe: comparisons with general population. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. May 31 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Safren SA, Hendriksen ES, Smeaton L, et al. Quality of life among individuals with HIV starting antiretroviral therapy in diverse resource-limited areas of the world. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(2):266–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA. 1995;273(1):59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Wu AW, Rubin HR, Mathews WC, et al. A health status questionnaire using 30 items from the Medical Outcomes Study. Preliminary validation in persons with early HIV infection. Med Care. 1991;29(8):786–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Wu AW. Quality of life assessment comes of age in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2000;14(10):1449–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Murri R, Fantoni M, Del Borgo C, et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life in HIV-infected patients. AIDS Care. 2003;15(4):581–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Briongos Figuero LS, Bachiller Luque P, Palacios Martin T, Gonzalez Sagrado M, Eiros Bouza JM. Assessment of factors influencing health-related quality of life in HIV-infected patients. HIV Med. 2011;12(1):22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Degroote S, Vogelaers D, Vandijck DM. What determines health-related quality of life among people living with HIV: an updated review of the literature. Arch Public Health. 2014;72(1):40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Mutabazi-Mwesigire D, Katamba A, Martin F, Seeley J, Wu AW. Factors That Affect Quality of Life among People Living with HIV Attending an Urban Clinic in Uganda: A Cohort Study. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0126810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Stangl AL, Wamai N, Mermin J, Awor AC, Bunnell RE. Trends and predictors of quality of life among HIV-infected adults taking highly active antiretroviral therapy in rural Uganda. AIDS Care. 2007;19(5):626–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Jaquet A, Garanet F, Balestre E, et al. Antiretroviral treatment and quality of life in Africans living with HIV: 12-month follow-up in Burkina Faso. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Safren SA, Biello KB, Smeaton L, et al. Psychosocial predictors of non-adherence and treatment failure in a large scale multi-national trial of antiretroviral therapy for HIV: data from the ACTG A5175/PEARLS trial. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e104178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).La Rosa AM, Harrison LJ, Taiwo B, et al. Raltegravir in second-line antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings (SELECT): a randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority study. Lancet HIV. 2016;3(6):e247–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).World Health Organizetion (WHO). Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents. In. Genebra; 2010. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44379/1/9789241599764_eng.pdf; Accessed November 10, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16).World Health Organizetion (WHO). Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection Recommendations for a public health approach. In. Genebra; 2016. 2nd Edition Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/arv/chapter4.pdf?ua=1 ; Accessed November 10, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Crystal S, Fleishman JA, Hays RD, Shapiro MF, Bozzette SA. Physical and role functioning among persons with HIV: results from a nationally representative survey. Med Care. 2000;38(12):1210–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Wu AW, Hays RD, Kelly S, Malitz F, Bozzette SA. Applications of the Medical Outcomes Study health-related quality of life measures in HIV/AIDS. Qual Life Res. 1997;6(6):531–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Arpinelli F, Visona G, Bruno R, De Carli G, Apolone G. Health-related quality of life in asymptomatic patients with HIV. Evaluation of the SF-36 health survey in Italian patients. Pharmacoeconomics. 2000;18(1):63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Bing EG, Hays RD, Jacobson LP, et al. Health-related quality of life among people with HIV disease: results from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Qual Life Res. 2000;9(1):55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Call SA, Klapow JC, Stewart KE, et al. Health-related quality of life and virologic outcomes in an HIV clinic. Qual Life Res. 2000;9(9):977–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Carrieri P, Spire B, Duran S, et al. Health-related quality of life after 1 year of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2003;32(1):38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Hsiung PC, Fang CT, Chang YY, Chen MY, Wang JD. Comparison of WHOQOL-bREF and SF-36 in patients with HIV infection. Qual Life Res 2005;14(1):141–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Aids Clinical Trials Group (ACTG). Appendix 60. Versiion 1.2; January 2009. Available at: http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article/asset?unique&id= info:doi/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001290.s019. [Google Scholar]

- 25).World Health Organizetion (WHO). Interim WHO clinical staging of HIV/AIDS and HIV/AIDS case definitions for surveillance WHO/HIV/2005.02. In. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/clinicalstaging.pdf; Accessed October 13, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26).1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR Recomm Rep, 1992;41(RR-17):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).Liu C, Johnson L, Ostrow D, Silvestre A, Visscher B, Jacobson LP. Predictors for lower quality of life in the HAART era among HIV-infected men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42(4):470–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Bajunirwe F, Tisch DJ, King CH, Arts EJ, Debanne SM, Sethi AK. Quality of life and social support among patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in Western Uganda. AIDS Care. 2009;21(3):271–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Fan AP, Kuo HC, Kao DY, Morisky DE, Chen YM. Quality of life and needs assessment on people living with HIV and AIDS in Malawi. AIDS Care. 2011;23(3):287–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).Anand D, Puri S, Mathew M. Assessment of Quality of Life of HIV-Positive People Receiving ART: An Indian Perspective. Indian J Community Med. 2012;37(3):165–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31).Tesfaye M, Kaestel P, Olsen MF, et al. Food insecurity, mental health and quality of life among people living with HIV commencing antiretroviral treatment in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14(1):37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32).Kamen C, Arganbright J, Kienitz E, et al. HIV-related stigma: implications for symptoms of anxiety and depression among Malawian women. Afr J AIDS Res. 2015;14(1):67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33).Bennett DS, Traub K, Mace L, Juarascio A, O’Hayer CV. Shame among people living with HIV: a literature review. AIDS Care. 2016;28:87–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34).Pedersen KK, Eiersted MR, Gaardbo JC, et al. Lower Self-Reported Quality of Life in HIV-Infected Patients on cART and With Low Comorbidity Compared With Healthy Controls. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;70(1):16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35).Hays RD, Cunningham WE, Sherbourne CD, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection in the United States: results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. Am J Med. 2000;108(9):714–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36).Henderson M, Safa F, Easterbrook P, Hotopf M. Fatigue among HIV-infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med. 2005;6(5):347–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37).Magafu MG, Moji K, Igumbor EU, et al. Usefulness of highly active antiretroviral therapy on health-related quality of life of adult recipients in Tanzania. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(7):563–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38).Davies AR, Ware JE, United States. Department of Health and Human Services ., Rand Corporation. Measuring health perceptions in the health insurance experiment. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corp.; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 39).Stewart AL, Ware JE. Measuring functioning and well-being : the medical outcomes study approach. Durham: Duke University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 40 ).Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE Jr. The MOS short-form general health survey. Reliability and validity in a patient population. Med Care. 1988;26(7):724–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41).Ware J SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 42).Veit CT, Ware JE Jr. The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. J Consult Clin Psychol 1983;51:730–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]