Abstract

HIV has reached epidemic proportions among African Americans in the USA but certain urban contexts appear to experience a disproportionate disease burden. Geographic information systems mapping in Philadelphia, indicates increased HIV incidence and prevalence in predominantly Black census tracts, with drastic differences across adjacent communities. What factors shape these geographic HIV disparities among Black Philadelphians? This descriptive qualitative study was designed to refine and validate a conceptual model developed to better understand multi-level determinants of HIV-related risk among Black Philadelphians. We used an expanded ecological approach to elicit reflective perceptions among administrators, direct service providers, and community members about individual, social, and structural factors that interact to protect against or increase the risk for acquiring HIV within their community. Gender equity, social capital, and positive cultural mores (e.g., monogamy, abstinence) were seen as the main protective factors. Historical negative contributory influences of racial residential segregation, poverty, and incarceration were the most salient risk factors. This study was a critical next step toward initiating theory-based, multi-level community-based HIV prevention initiatives.

Keywords: AIDS, HIV, structural factors, African Americans, Black, Epidemic Determinants, USA

Background

In the USA, new HIV infections have stabilised around 50,000 reported cases each year, however, disease burden remains pervasively disproportionate (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2015a; amfAR 2014). Black Americans account for nearly half of all new HIV infections (44%), despite representing only 15.2% of the total US population. Estimates indicate that one in 16 Black men and one in 32 Black women will be diagnosed with HIV at some point in their lifetimes (CDC 2015b).

Prevention efforts aimed only at the individual level have fallen short of reducing disproportionate disease burden among Blacks (de Wit et al. 2011, & Crewe, 2011). Larger social and structural issues may put some individuals at increased risk for contracting HIV (Adimora and Schoenbach 2012; Friedman, Cooper, and Osborne 2009; Rhodes et al. 2005), including neighbourhood condition, imbalanced male-female sex ratios, and gender-based violence and discrimination (Hodder et al. 2013; Kelly-Hanku et al. 2015; Kerr et al. 2015; Adimora et al. 2014; Blankenship and Smoyer 2013; Dean and Fenton 2010). This highlights an urgency to move beyond individual-level approaches to multi-level designs to address the epidemic (Auerbach, Parkhurst, and Cáceres 2011).

The local Philadelphia epidemic continues to have a profound impact on the city’s overall health. In 2014, Black Philadelphians represented 68% of all newly diagnosed HIV cases, 73% of newly diagnosed AIDS cases, and 64% of all prevalent HIV and AIDS cases (Philadelphia Department of Public Health (PDPH) 2015). The prevalence rate among Black men who have sex with men exceeded 30,000 per 100,000, and these rates are steadily increasing (PDPH 2015). Additional disparities are noted among Black people who identify as transgender (male-to-female or female-to-male) versus those who identify as male or female (70% and 83.3% versus 59.9% and 72.6% respectively; PDPH 2015). Nationwide, marginalised individuals of multiple minority statuses (e.g., racial/ethnic and sexual minority status) bear the brunt of poorer HIV-related outcomes (Brennan et al. 2012; Garcia et al. 2016).

Higher incidence and prevalence of HIV in Black communities may partially explain disparate rates of HIV and AIDS (CDC 2015b). An individual’s geographical context may in fact mediate his/her risk of acquiring HIV (Nunn et al. 2014; Brawner 2014). Beyond racial composition, social and structural conditions in neighbourhoods (e.g., crime, vacant parcels) are associated with increased HIV prevalence (Brawner et al. 2015; Bowleg et al. 2014; Raymond et al. 2014). Social research suggest both social and economic environments influence sexual behaviours which can, in turn, influence risk for HIV (Gillespie, Kadiyala, and Greener 2007; Parker, Easton, and Klein 2000). Structural determinants (e.g., economic inequalities) are also important in understanding the transmission and prevention of HIV (Hardee et al. 2014; Sumartojo 2000). Examining individual, social and structural determinants of HIV transmission is critical for designing evidence-informed, multi-level, complex models of HIV prevention. We hypothesise that identifying and addressing these broader multi-level concerns within neighbourhoods will improve outcomes among residents (Lewis et al. 2016).

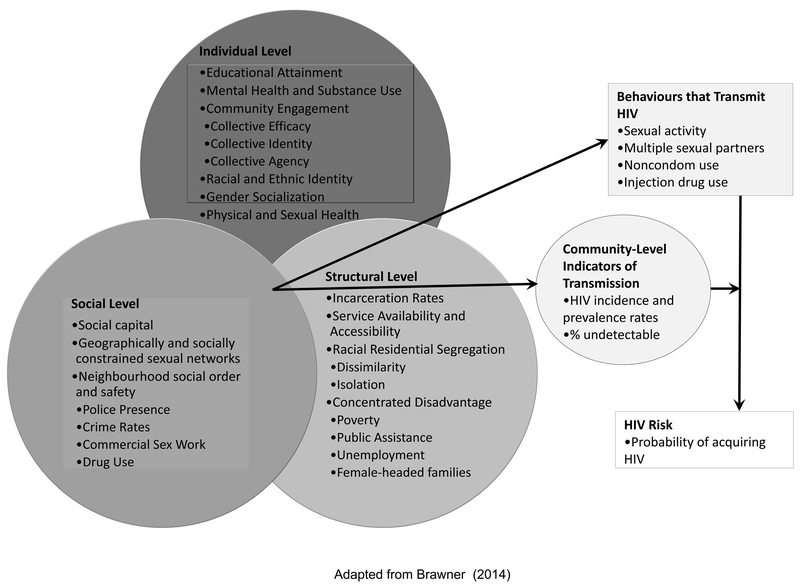

When developing conceptual models, which are crucial to intervention development, qualitative research helps to engage community partners to check researcher assumptions (Maxwell 2012). We aimed to explore service administrators’, direct service providers’ and community members’ perceptions of individual, social, and structural factors that interact to protect against or increase Black Philadelphians’ risk for acquiring HIV. Our intent in engaging multiple stakeholders in the discussion was to refine and validate a conceptual model, developed by the lead author (BB), to better understand multi-level influences on HIV risk among Black Philadelphians. This expanded ecological model was based on our previous research with the same population, as well as a review of relevant literature(Brawner 2014); see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Multi-level conceptual model of HIV among Black Philadelphians

Methods

Design and Sample

In our ongoing immersion in the local HIV prevention landscape, we have engaged Black Philadelphians in iterative conversations and elicitation research for more than a decade. This extensive community engagement, and knowledge of relevant literature, guided a researcher-developed model of the multi-level determinants of HIV risk among Black Philadelphians. We examined our conceptualisations through member-checking and group model building activities. This included monthly meetings with an adult community advisory board to provide feedback on the investigators’ interpretations. Member-checking in the form of verification of data with the engaged group, is key to establishing the validity and trustworthiness of the data (Creswell and Miller 2000; Clark and Creswell 2011). Group model building is a specific participatory method used to involve stakeholders in the model development process (Schensul, Schensul, and LeCompte 2012; Hovmand et al. 2012).

In this paper, we report on a novel approach that served as both a member-checking and group model building activity. We held a focused conversation with 10 stakeholders (three administrators, three direct HIV/AIDS service providers and four community members) on individual, social, and structural factors related to Philadelphia’s high HIV rates. Although group heterogeneity reduced the sample size for each stakeholder type, we believed it was important to elicit their voices and perspectives in conversation with each other to explore similarities and differences (e.g., administrator versus direct service providers). Combining multiple stakeholders in one group also enabled us to see how well the group member’s varied perceptions reflected the researcher-developed model. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pennsylvania. Data were collected in January 2012 via a group discussion in a private conference room at the University.

One, 3-hour focus group discussion was held with stakeholders aged 18 and above. In focus group methodology, the “trade-off between number of focus groups and the thickness of the description [is] an acceptable explanation for (a limited) sample size” (Carlsen and Glenton 2011, 10). We sought a sample with representation from the most experienced and knowledgeable stakeholders (Hovmand, Nelson, and Carson 2012). For us, this meant engaging a diverse array of leaders and community residents in an area highly affected by HIV. Participants were recruited through flyers, emails, word of mouth and street intercepts. They were eligible if they were aged 18 or older and lived, worked and/or had a vested interest in the Philadelphia census tract with the highest HIV and AIDS rates in the city, identified using publicly available data from AACO (PDPH 2008). The study design restricted the group to 10 participants, and we sought to have near equal numbers per stakeholder type. While administrators and direct service providers might hold similar views on the topic, both groups work in the HIV field; thus we expected some overlap in their responses. Because we wanted as much diversity from the community as possible, given the limitations of the study design and budget, we allocated the 10th slot to the community category. The selected census tract has a total population of 6,983 (97.2% Black), of whom 65.5% have at least a high school diploma or GED, and 36.5% live below the US federal poverty level (U.S. Census Bureau 2000). Exclusion criteria were below 18 years of age, or a cognitive or psychiatric condition prohibiting a participant’s ability to complete the study procedures, as determined by trained research assistants during screening. Participants received $50 cash for their participation.

Measures and Procedures

After consenting, participants completed a 5-minute sociodemographic questionnaire (e.g., age, income). A trained facilitator conducted one 3-hour focused group discussion. The facilitator followed a semi-structured focus group script, with items derived from the conceptual framework. Participants were asked to consider how individual, social, and structural factors related to Philadelphia’s high HIV rates, as risk or protective factors. Individual-level factors were defined as “past experiences, current situations or daily occurrences that are part of a person’s life at any given moment in time”(e.g., gender socialisation; Brawner 2014). Can you tell us some things that are unique to Black Philadelphians compared to other racial or ethnic groups? Social-level factors were defined as “things that are socially or culturally accepted, relationships and connections that Black Philadelphians have with other people, and values and beliefs in Black society” (e.g., social capital; Brawner 2014). What are some things that are socially or culturally accepted in the Black Philadelphia community? Structural-level factors were defined as “things that have happened over time, and/or continue to happen, which shape the environment people live in and the things they see and experience on a daily basis” (e.g., institutionalised discrimination; Brawner 2014). Can you tell us any connections you see between the neighbourhoods many Black Philadelphians live in and HIV/AIDS?

The researcher-developed model was not shown to the participants so as to obtain their uninfluenced views. We employed free listing to identify participants’ salient ideas regarding factors at each level (Colucci 2007). The research staff wrote the participants’ responses on easel paper. These responses were posted around the room while the facilitator moderated the discussion. As stakeholders identified factors, they were asked to determine whether the factor was an HIV transmission risk or protective factor, and to brainstorm solutions to factors identified at each level. This process was repeated until the individual, social and structural levels were all discussed.

Data Analysis

The focus group discussion was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. This information was supplemented with notes taken by research staff during the discussion. The research team used a combined deductive and inductive coding methodology (Bradley, Curry, and Devers 2007) finalised by the lead and second authors. For deductive coding, a priori codes were created based on the conceptual model. For inductive coding, emergent codes were created from the participant narratives. Two trained independent coders conducted the analyses using NVivo 10 software. Discrepancies between the coders were resolved in team meetings, with final decisions made by the lead author. Analysis began with descriptive and interpretive coding, and then advanced as the researchers compared emerging thematic categories to the raw data. Descriptive statistics were calculated for the sociodemographic questionnaire using SPSS 21.

Results

All ten participants self-identified as African American; nine were women, there was only one man. The average age was 31.3 (range 19–50 years). All participants had a high school diploma or general educational development (GED) certificate; three had completed postgraduate work. Only one participant was unemployed. Four participants reported an annual household income less than $40,000. Three received public assistance.

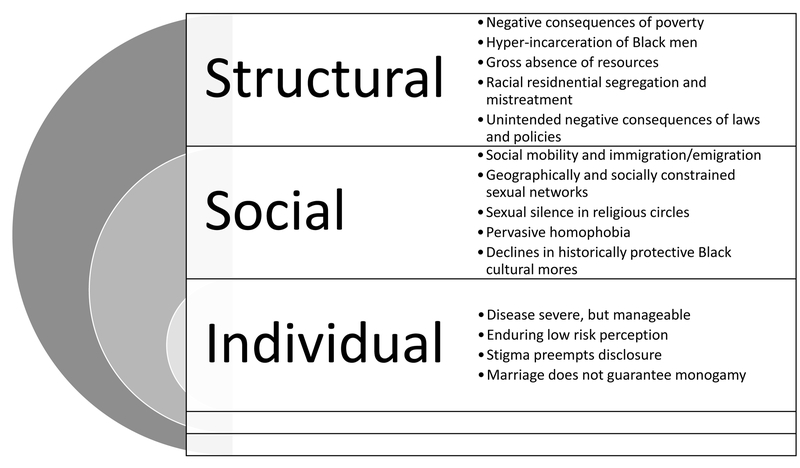

Several themes emerged from the data (see Figure 2). The four individual-level themes were: HIV/AIDS is a severe but manageable disease; there is enduring perception of low risk in the Black community despite disproportionate disease burden; pervasive stigma may prevent an HIV-positive person’s desire/responsibility to disclose; and marriage does not guarantee monogamy. The five social-level themes were: social mobility and immigration/emigration; geographically and socially constrained sexual networks; sexual silence in religious circles; pervasive homophobia; and decline in historically protective Black cultural mores, such as abstinence and monogamy. The five structural-level themes were: negative consequences of poverty; hyper-incarceration of Black men fuels HIV transmission; gross absence of appropriate required/resources; racial residential segregation and mistreatment; and unintended negative consequences of laws and policies. The responses to the free listing activity are presented in Table 1 (see online appendix). The quotes below are presented verbatim except where otherwise noted.

Figure 2.

Focus group themes.

Individual-level Factors

Disease severe, but manageable

HIV/AIDS was viewed as a “deadly,” “incurable” disease, “primarily affecting people of colour”. All participants, however, agreed that “it’s [also] a manageable condition, just like any other chronic condition, people can live with it if they manage it appropriately.” They described HIV/AIDS as a condition that does not have to be fatal, but will be without proper self-care (e.g., medication adherence).

Enduring Low Risk Perception

The group identified large U.S. cities (e.g., Philadelphia), Africa and nursing homes as places that come to mind when they think about HIV/AIDS. They noted, “It’s affecting a lot more people than we think” and “it’s getting a lot [younger] nowadays”. One participant was shocked to discover that HIV rates were high in certain areas; “…you would think it would be…in the gay communities or more so downtown...” They all believed that Blacks in the USA and other countries are disproportionately affected. While the participants acknowledged increased risk for HIV among Blacks, the majority believed that most members of the Black community perceive HIV risk as low. As one participant noted:

“…You hear many stats and it might be related to men who have sex with men so many times people who are not men who have sex with men think, ‘oh I’m not at risk, that only happens to those people’, and I think that plays a big part of people not taking the precautions to protect themselves.”

For these reasons, the group believed that many Black Philadelphians who need to be tested for HIV do not get tested. Without being tested, people will not know their HIV status, and without knowing their status, they won’t know that they are potentially transmitting the virus to others. Several administrators and service providers discussed the implications of “high viral load”,

“cause if you have a high viral load that means it’s a lot of virus in your body and it’s a lot of virus in your body that’s going to be easier for you to transmit it if you’re having sex with somebody...”

Stigma Preempts Disclosure

Many participants believed that a person’s HIV status is only his or her “business”. As one stated, “I don’t think they should have to publicly tell people or anything like that, or be treated or looked at any differently.” The ramifications of disclosure were perceived to be severe not only with sexual partners, but also employers, neighbours, etc. Some, however, thought that disclosure was important and almost mandatory: “A lot of people don’t be honest with themselves like to say, ‘oh I got AIDS’, you know, let somebody know that I have AIDS whether I’m going to have sex with them or not.”

Marriage does not Guarantee Monogamy

Although marriage can be a protective factor, “false” perception of low risk among married people was seen as a risk factor. Participants noted that although monogamy is presumed in marriage, spouses can be exposed to risk when one or both partners “steps outside of the marriage”. “[Marriage] doesn’t mean you’re in a monogamous relationship.” One female participant recounted an experience with HIV testing:

“you know you think you’re married and you think you’re in this type of relationship and you don’t have to worry about these things…[the HIV tester] kind of called me to the carpet…and was like ‘it doesn’t matter who you are having unprotected sex with’.”

Most participants felt that cultural and societal norms do not promote or encourage HIV testing in marriage because of the assumption that both partners are HIV negative and monogamous.

Social Factors

Social Mobility and Immigration/Emigration

Social mobility and immigration/emigration were discussed as contributors to the rapid spread of HIV. Participants thought that HIV was selective, affecting specific populations such as people living in poverty or immigrants from countries with high HIV rates. “Looking at the population of African Americans and the population of like West African immigrants… knowing that those are the people that the disease is affecting so rapidly and [they are] growing so rapidly here.” This sentiment placed the blame for infection on already-infected immigrants. At the same time, they believed that accessible public transportation eases interaction across neighbourhoods which facilitates HIV transmission from high to low prevalence neighbourhoods: “So you can be living…where HIV rates may not necessarily be high, but you get on the [bus] and 35, 45 minutes you are smack dab in [a high prevalence area]”.

Geographically and Socially Constrained Sexual Networks

The group reported that geographic and social constraints can increase HIV risk (e.g., choosing sexual partners only from certain neighbourhoods or racial/ethnic groups with elevated HIV prevalence):

“…if you’re in a community where there’s a lot of HIV that increases your chances of coming in contact with someone HIV-positive. So it’s not necessarily that I have to go out and sleep with 5, 10 guys in that neighbourhood it might be that one guy because there are a lot of people that have HIV, that increases my chances of coming in contact with that one person that’s positive.”

They also discussed the growing acceptance of interracial relationships in the Black community, and the perceived risks that other groups face when this happens. One participant shared a conversation she had with a White friend who “only dates Black men”:

“…keep in mind that now you are a Black woman when it comes to race and your risks for HIV…I mean on the outside you look White, on the inside its been Black men all up and through there.”

She described how with elevated HIV rates in the Black community, any woman, Black or otherwise, faces the same risks. When structural factors constrain choice of partner to those in spaces and networks where HIV is prevalent, partners are more likely to be exposed to infection.

Sexual Silence in Religious Circles

Religion was noted to be either a protective or risk factor. The dividing line for risk/protection was whether religious tenets supported people and/or instilled shame, and whether or not religious leaders were forthcoming with sexual health information:

“…we have a strong religious community in Philadelphia that may allow for social support for folks that are HIV-positive but also…you do not have folks that feel like they can talk…about their actual sexual activity. So, I’m going to church, I’m not actually sharing with the deaconess that I’m getting it in [having sex frequently]…which means I might not be getting accurate information about HIV transmission.”

The group gave several accounts of Philadelphia churches that are actively combating HIV/AIDS, and supporting HIV-positive people. Overall, however, the sentiment was that the Black church was still not doing enough around the local epidemic. Moreover, silence about sex and HIV in religious circles and within families, was seen as a driving undercurrent. Participants noted that despite this silence, congregants are still engaging in risk behaviours:

“my grandmother was an evangelist and my grandfather was a pastor, so there was no sex education…’[we’ll] have that conversation with you when you are an adult and when you could possibly be getting a husband’, and then, meanwhile, you been getting it in.”

Pervasive Homophobia

The group noted that over time more people have become “more accepting of it” (homosexuality), but “the LGBTQ population” is still marginalised and stigmatised. They stated that same sex sexual partnerships are becoming more prevalent and “getting…younger and younger”. The “down low” and men who have sex with men were seen as major contributors to the epidemic among Blacks. The overarching belief was that cultural norms and taboos about same sex relationships were further marginalising and isolating those at increased risk. More culturally unacceptable behaviours (e.g., men having anal sex with other men) were being driven underground, thus contributing to risk in Black populations.

Declines in Historically Protective Black Cultural Mores

Black cultural mores—caring neighbourhoods, respect for one another, and abstinence until marriage—incited the liveliest discussion among participants. Particularly around the decline in values that were historically protective of HIV (e.g., mutual monogamy). Lack of social cohesion and/or concern for others was also reflected: “It ain’t in my house so I ain’t worried about it”. The group discussed how “children out of wedlock” and single parenting has become the norm and acceptable and that new values are inconsistent with marriage and long-term committed partnerships. Multiple sexual partners and promiscuity were reported to be promoted and encouraged, particularly through peer expectations and media outlets.

“… ‘a girl will give you her body before she give you her name.’ I strongly believe that ‘cuz so many girls nowadays don’t even know the boy last name, you don’t even know his real name ‘cuz they call him his street name.”

Norms around educational attainment, and contradictory cultural affirmations were also explored. They described that when someone goes to college the narrative is “oh you think you’re smarter than everybody,” but when someone gets home from prison “it’s block parties, barbeques”. Further, the desire for “street cred” (credibility usually attained through illegal activity) was seen as a risk factor. Drug culture was perceived to be endorsed and accepted because “they making more money hustling than going to work”. The negative consequences of social media were also discussed, particularly as youth use it as a means to join together to do “bad things” (e.g., fighting).

Structural Factors

Negative Consequences of Poverty

Poverty was seen as a primary structural determinant of HIV transmission, and participants described their perceptions of Philadelphia’s economic viability: “Philadelphia is the most impoverished city out of the 10 largest”. The group described the connection between poverty and social injustices, and the effect these factors have on one’s health:

“… wherever you see poverty, low education, and low socioeconomic status and you know unemployment, and public housing, you know the trends of any disease are going to follow that…HIV…heart disease…diabetes.”

The ramifications of poverty on access to quality care were also discussed and the participants noted that many people in the Black community are uninsured or underinsured.

Hyper-incarceration of Black Men

The institutionalisation of HIV in the prison system was seen as a prominent cause of elevated HIV rates among Black Philadelphians: “The prison in particular… ya know a lot of our folks are being shipped to the streets from the prison system with HIV infection and subsequently coming back to the community.” They also discussed risks associated with having unprotected sex with partners who may have acquired HIV while incarcerated after their release, especially in the absence of conversations regarding fidelity and HIV testing: “And when he come home you don’t use protection cause he been in jail, you know where he was at all that time…But you don’t know what he been doing…And he don’t know what you been doing.” One participant also recounted the historical influences of the prison system on Philadelphia’s current HIV rates:

“… we had that influx of crack/cocaine…So a lot of things happened in the 80s that exacerbated the HIV/AIDS rates and made HIV one of those conditions that is embedded in prisons, nationally…HIV became an institutionalised condition from that point forward.”

Gross Absence of Resources

The group dialogued about how Black neighbourhoods have an abundance of bars, liquor stores and welfare offices, but lack relevant resources such as health centres and supermarkets: “No kind of, you know, organisations that provide service or information….No kind of help, no kind of resources.” The effect of school budget cuts, including strained resources, on the type of education youth receive about sex and HIV was also noted. The historical and intergenerational repercussions of these economic downturns were highlighted, particularly connecting limited education to teenage pregnancies:

“…a lot of the parents had these kids at 13, 14, 15 years old. They didn’t get that far in their education…So now we have people that don’t have these values trying to instill these values and you don’t really know how to do that”.

They also noted that in more affluent areas of the city, organisations were present and provided people with incentives (e.g., food, condoms) while the most heavily affected areas were HIV resource deserts. As one participant described, “you ain’t going to hear none of that, ain’t nobody giving out nothing [related to HIV]. If anything you got the girl on the corner that’s ready to take you to a house [for sex trade]...”

Racial Residential Segregation and Mistreatment

The participants talked about the negative effects of racial residential segregation and gentrification in displacing Blacks from their neighbourhoods: “You have White people moving into these Black neighbourhoods, and pushing the Black people out”. The group had mixed opinions on whether racial residential segregation was a positive or negative factor. Some people thought it was beneficial because Black people are “comfortable around other Black people”, while others believed it was the lingering effect of unjust policies. They highlighted, however, that these factors concentrate Blacks into more impoverished areas where HIV is more concentrated. Unfinished construction projects, unfixed potholes and burned down homes that are not restored (which are widely prevalent in some Philadelphia communities) were seen as problematic. “So it’s like their secluding the people in those neighbourhoods when they don’t finish those projects.” Dilapidated environments were believed to cause people not to care about their neighborhoods or themselves. Drastic differences were also noted across neighbouring blocks, “you know you can go 4 blocks one way and be in the straight hood.” The way Black people are mistreated and profiled was also expressed:

“… they was racial profiling…You can’t catch that last train cuz they was guaranteed to stop you. ‘Where you coming from, who are you wit, why’?, and ya bags be searched…certain people are just not going to be ok wit it wherever you live or they just don’t feel like it’s ok for African Americans to live there…’It’s ok that they’re [White people] starting trouble, because you’re African American,’...”

This sustained mistreatment is internalised, resultantly shaping how people view themselves and engage in self-care behaviours.

Unintended Negative Consequences of Laws and Policies

Participants discussed the unintended negative consequences of universal testing and entitlements for HIV-positive people. Universal testing without counselling was believed to bypass counselling, leading to continued risk behaviours in the absence of risk-reduction education. Entitlements were perceived as having a “welfare” effect such that some HIV-positive people who could work would choose not to since it was optional. “So at some point in the 90s it became fashionable to be HIV-positive and get housing and financial entitlements.” Another participant remarked that “people always find a way to loop the system”, suggesting that people might not take preventive measures because if they acquired HIV they would not have to work.

Strengths, Solutions and Strategies for Intervention

Despite the daunting list of concerns, the group discussed strengths, as well as possible solutions to the identified risk factors (see Table 1). They believed that with appropriate resources and investment, factors such as unemployment and poverty could be changed. The following were listed as solutions that could be implemented to address HIV among Black Philadelphians: creation of job opportunities, building up of neighbourhoods and community cohesion, development of additional cente=res (including for substance abuse and mental health treatment), improvement of after school programmes, promotion of gender equity (to reduce homophobia and stigmatisation), encouragement of parental support with youth, advocacy of comprehensive sexual health education, and promotion of cultural norms congruent with abstinence and/or mutual monogamy.

Participants acknowledged that these changes “won’t be overnight,” but unanimously agreed that we would have to start somewhere. They also talked about the importance of holding “celebrities” accountable to giving back to the community saying, “they take all our money but can’t educate us…” They talked about the powerful social influence celebrities possess that can be harnessed to address concerns in the Black community, including HIV/AIDS:

“When they [celebrities] wanted Obama in the election they made it clear…But now, as far as AIDS, get all those same people involved…to say ‘it’s not ok, if you are having [sex] there’s ways to protect yourself from [HIV]’...”

“…’I just got tested and I’m hoping that my results are negative’…that’s what I need them all to say.”

The importance of capitalising on free resources such libraries, health centres and community-based organisations that could sponsor different events was also discussed. They suggested that sponsors offer free HIV testing instead of giving out t-shirts, and talk about their own testing experiences. Social media, word of mouth, media campaigns and advertisements with discounts to restaurants were identified as effective means to share information about HIV prevention.

Discussion

The findings from this study uncover key stakeholders’ perceptions of intersectional influences of individual, social, and structural factors on increased risk for or protection against HIV. Unique to this study, we incorporated a mix of perceptions among administrators, direct service providers and community members as to how these multi-level factors distinctively influence HIV risk among Black Philadelphians. Bringing them together elucidated shared perspectives, reinforced orientation to community change, and provided better understanding of community dynamics. From the group narrative, the effects of neighbourhood disadvantage and disinvestment on health and social outcomes were evident. The findings support the fact that “place matters” in relation to individual and population health (LaVeist, Gaskin, and Richard 2011; Massey 2013).

Place-based approaches to understanding disparate HIV and AIDS rates within racial/ethnic minority communities seek to understand stakeholders’ perceptions and beliefs about how fundamental structural and social factors such as incarceration, employment, education, poverty, housing, and transportation influence disparate HIV and AIDS rates within the community (Dauria et al. 2015). These structural and social factors cannot be ignored but must be addressed from multi-level perspectives such as engaging affected communities and associated political bodies (Auerbach, Parkhurst, and Cáceres 2011; Blackstock et al. 2015); including immigrants who face unique structural and cultural barriers to care (Foley 2005). We argue that this should begin with convening a diverse profile of community stakeholders, who live, work, play, learn and have a vested interest in highly affected areas.

Similar to other studies, our findings highlight the role of Black cultural mores in HIV and AIDS (Tobias 2001). Participants described the decline of positive aspects of Black culture such as social accountability and reciprocity as contributory to HIV risk. Moreover, discoveries of enduring low risk perception coupled with poorly attributed risk (e.g., focusing on men who have sex with men while ignoring infidelity in married couples) have significant implications for HIV prevention messaging and risk reduction. Community-based approaches can tap into these historical sources of strength, in culturally meaningful ways to foster positive cultural norms and promote sexual health in Black communities. While not elicited from our data, specific emphasis on social-structural interventions for women and girls (e.g., creating gender-equitable relationships, decreasing violence among women) is also crucial to ending the AIDS epidemic as a public health threat (Hardee et al. 2014).

Acknowledging community stakeholders’ perceptions, attitudes, beliefs, and recommendations provides an essential guide for developing multi-level, community-based HIV prevention strategies that are responsive and sensitive to the prioritized communities (Prather et al. 2012; Smedley 2014; Cummins et al. 2007). Our findings extend the literature and strongly point to the need to develop a four-prong strategic approach to addressing disproportionate HIV burden in communities. First, we should galvanise invested stakeholders and elucidate strategies to address the local HIV and AIDS endemics (Walcott et al. 2016). Those at the margins (e.g., multiple minority statuses, lower income) must be included in these processes (Auerbach, Parkhurst, and Cáceres 2011). Second, we need to understand and address stigma/pervasive myths to bolster HIV and AIDS awareness and informed sexual decision-making. This includes intervening against generalised homophobia (Garcia et al. 2016), Black men’s ideology that they cannot decline sex (Bowleg et al. 2011) and the normativity of infidelity by Black women (Bowleg, Lucas, and Tschann 2004). Third, we need an intergenerational approach, with the engagement of families (Adimora and Schoenbach 2012), as well as key community institutions such as Black churches (Stewart 2015). Last and most important is to understand how the intersectionality and lived experience of racism, gender-based discrimination and stigma influence HIV and AIDS disparities (Smedley 2014; Bowleg 2013; Bowleg et al. 2013), particularly among those who experience multiple forms of marginalisation. Safe spaces are needed for social support and stigma reduction, as well as for HIV testing and treatment (Garcia et al. 2015). Gender differences, including masculine ideologies that promote concurrent sexual partnerships and HIV risk behaviours among older Black women, should also be considered (Bowleg et al. 2011; Smith and Larson 2015).

Of theoretical and methodological interest, the way we used the focus group discussion in an attempt to validate and/or modify our existing model was extremely beneficial. Overall, participants’ perceptions of the individual, social, and structural factors coincided with the researcher developed model. A comparison of Figure 1 with Table 1 shows that participants confirmed all of the factors already identified in the researcher-developed model. They did, however, ascribe some of the factors to different levels or use different terminology. Further, they identified additional factors that the investigators had not considered. Factors that could not be integrated easily because of poor conceptual fit, such as interracial relationships, have been incorporated into ongoing studies to honor their input. The invaluable exercise helped us consider programming directions, as well as build relationships with new stakeholders.

Most HIV research rests on researcher driven models. A community-based approach ensures that community stakeholders have a stake in sharing their understanding of the problem and helping to devise solutions to it (Prather et al. 2012; Schensul, Schensul, and LeCompte 2012; Schensul, Berg, and Nair 2013). Many important HIV prevention studies focus on the individuals affected by the problem and the circumstances in their lives that make it difficult to protect themselves and others (Fleming et al. 2014; DiCarlo et al. 2014). Fewer, however, ask stakeholders from different sectors of the community their views on the structural determinants of HIV or help them make connections between social and structural factors, and individual behaviours (Walcott et al. 2016). Since they were not shown the conceptual model, participants were unaware of specific factors that the researchers included on each model level, and generated ideas on their own. This emergent community-based participatory research methodology offers a new approach to model testing and validation, and the simultaneous creation of supportive infrastructure and collaboration in multi-level intervention design.

The limitations of this study must be acknowledged. The small, heterogeneous convenience sample of 10 participants and focused geographic location limits the generalisability of the findings. With only three or four participants per stakeholder type, we cannot presume that these data represent the voices of all administrators, direct services providers or community members in the study area. Focus groups are also shaped by participants, their experiences and the multiple social contexts that affect their lives. Mixing multiple stakeholders in one group may have fostered problematic silences of speech (Hollander 2004). However, all group members contributed to the discussion and none of the topics, though sensitive, seemed to impair participants’ expression of their opinions. Further, the intent was to elicit information from a diverse group of Philadelphia’s stakeholders. Hearing their collective voice provided data that may not have otherwise been obtained (Hovmand, Nelson, and Carson 2012). The insight gained from the discussion was rich and contributes new information about this topic to the literature. Future studies are needed with larger samples, and mixed methods approaches, as well as a broader sampling of geographic locations.

In addition to individual risk behaviours, HIV rates are fuelled by social and structural factors that contribute to health inequities. Community-level approaches to HIV prevention may be most effective when they address the impact of multi-level influences on the epidemic, and when they involve stakeholders in that process. This study is a preliminary step in that direction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health under Grant number 5R25MH087217–04 (PIs B. Guthrie; J. Schensul; and M. Singer). The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health. The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Adimora Adaora A, and Schoenbach Victor J. 2012. “Social Determinants of Sexual Networks, Partnership Formation, and Sexually Transmitted Infections” In The New Public Health and STI/HIV Prevention, edited by Aral SO, Fenton KA and Lipshutz JA, 13–31. New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Adimora Adaora A., Ramirez Catalina, Schoenbach Victor J., and Cohen Myron S.. 2014. “Policies and politics that promote HIV infection in the Southern United States.” AIDS 28 (10):1393–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- amfAR. 2015. “Statistics: United States.” Accessed October 9. http://www.amfar.org/About-HIV-and-AIDS/Facts-and-Stats/Statistics--United-States/.

- Auerbach Judith D., Parkhurst Justin O., and Cáceres Carlos F.. 2011. “Addressing social drivers of HIV/AIDS for the long-term response: Conceptual and methodological considerations.” Global Public Health 6 (suppl 3):S293–S309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstock Oni J, Frew Paula, Bota Dorothy, Vo-Green Linda, Parker Kim, Franks Julie, Hodder Sally L, Justman Jessica, Golin Carol E, and Haley Danielle F. 2015. “Perceptions of community HIV/STI risk among US women living in areas with high poverty and HIV prevalence rates.” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 26 (3):811–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship Kim M., and Smoyer Amy B.. 2013. “Between spaces: Understanding movement to and from prison as an HIV risk factor” In Crime, HIV and Health: Intersections of Criminal Justice and Public Health Concerns, edited by Sanders Bill, Thomas Yonette F. and Deeds Bethany Griffin, 207–21. Springer Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg Lisa. 2013. ““Once you’ve blended the cake, you can’t take the parts back to the main ingredients”: Black gay and bisexual men’s descriptions and experiences of intersectionality.” Sex Roles 68 (11–12):754–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg Lisa, Lucas Kenya J., and Tschann Jeanne M.. 2004. ““The ball was always in his court”: An exploratory analysis of relationship scripts, sexual scripts, and condom use among African American women.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 28 (1):70–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg Lisa, Neilands Torsten B., Tabb Loni Philip, Burkholder Gary J., Malebranche David J., and Tschann Jeanne M.. 2014. “Neighborhood context and Black heterosexual men’s sexual HIV risk behaviors.” AIDS & Behavior 18 (11):2207–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg Lisa, Teti Michelle, Malebranche David J., and Tschann Jeanne M.. 2013. ““It’s an uphill battle everyday”: Intersectionality, low-income Black heterosexual men, and implications for HIV prevention research and interventions.” Psychology of Men & Masculinity 14 (1):25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg Lisa, Teti Michelle, Massie Jenne S., Patel Aditi, Malebranche David, and Tschann Jeanne M.. 2011. “‘What does it take to be a man? What is a real man?’: Ideologies of masculinity and HIV sexual risk among Black heterosexual men.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 13 (5):545–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley Elizabeth H., Curry Leslie A., and Devers Kelly J.. 2007. “Qualitative data analysis for health services research: Developing taxonomy, themes, and theory.” Health Services Research 42 (4):1758–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawner Bridgette M. 2014. “A multilevel understanding of HIV/AIDS disease burden among African American women.” Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing 43 (5):633–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawner Bridgette M., Reason Janaiya L., Goodman Bridget A., Schensul Jean J., and Guthrie Barbara. 2015. “Multilevel drivers of Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome among Black Philadelphians: Exploration using community ethnography and geographic information systems.” Nursing Research 64 (2):100–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan Julia, Kuhns Lisa M., Johnson Amy K., Belzer Marvin, Wilson Erin C., and Garofalo Robert. 2012. “Syndemic Theory and HIV-related risk among young transgender women: The role of multiple, co-occurring health problems and social marginalization.” American Journal of Public Health 102 (9):1751–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedicte Carlsen, and Glenton Claire. 2011. “What about N? A methodological study of sample-size reporting in focus group studies.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 11 (1):26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015. “Black or African American Populations” Accessed October 9. http://www.cdc.gov/minorityhealth/populations/REMP/black.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015. “HIV Among African Americans” Accessed October 9. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/racialethnic/africanamericans/index.html

- Plano Clark, Vicki L. and Creswell John W.. 2011. “Designing and conducting mixed methods research” In.: Thousand Oaks, CA.: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Colucci Erminia. 2007. ““Focus groups can be fun”: The use of activity-oriented questions in focus group discussions.” Qualitative Health Research 17 (10):1422–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell John W., and Miller Dana L.. 2000. “Determining validity in qualitative inquiry.” Theory Into Practice 39 (3):124–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins Steven, Curtis Sarah, Diez-Roux Ana V., and Macintyre Sally. 2007. “Understanding and representing ‘place’in health research: A relational approach.” Social Science & Medicine 65 (9):1825–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauria Emily F., Oakley Lisa, Jacob Arriola Kimberly, Elifson Kirk, Wingood Gina, and Cooper Hannah L. F.. 2015. “Collateral consequences: Implications of male incarceration rates, imbalanced sex ratios and partner availability for heterosexual Black women.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 17 (10):1190–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit John B. F., Aggleton Peter, Myers Ted, and Crewe Mary. 2011. “The rapidly changing paradigm of HIV prevention: Time to strengthen social and behavioural approaches.” Health Education Research 26 (3):381–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean Hazel D., and Fenton Kevin A.. 2010. “Addressing social determinants of health in the prevention and control of HIV/AIDS, viral hepatitis, sexually transmitted infections, and tuberculosis.” Public Health Reports 125 (Supplement 4):1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiCarlo Abby L., Mantell Joanne E., Remien Robert H., Zerbe Allison, Morris Danielle, Pitt Blanche, Abrams Elaine J., and El-Sadr Wafaa M.. 2014. “‘Men usually say that HIV testing is for women’: Gender dynamics and perceptions of HIV testing in Lesotho.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 16 (8):867–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming Paul J., Barrington Clare, Perez Martha, Donastorg Yeycy, and Kerrigan Deanna. 2014. “Amigos and amistades: The role of men’s social network ties in shaping HIV vulnerability in the Dominican Republic.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 16 (8):883–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley Ellen E. 2005. “HIV/AIDS and African immigrant women in Philadelphia: Structural and cultural barriers to care.” AIDS Care 17 (8):1030–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman Samuel R., Cooper Hannah L. F., and Osborne Andrew H.. 2009. “Structural and social contexts of HIV risk among African Americans.” American Journal of Public Health 99 (6):1002–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonathan Garcia, Parker Caroline, Parker Richard G., Wilson Patrick A., Philbin Morgan, and Hirsch Jennifer S.. 2016. “Psychosocial implications of homophobia and HIV stigma in social support networks: Insights for high-impact HIV prevention among Black men who have sex with men.” Health Education & Behavior 43 (2):217–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonathan Garcia, Parker Caroline, Parker Richard G., Wilson Patrick A., Philbin Morgan M., and Hirsch Jennifer S.. 2015. ““You’re really gonna kick us all out?” Sustaining safe spaces for community-based HIV prevention and control among Black men who have sex with men.” PLoS One 10 (10):e0141326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie Stuart, Kadiyala Suneetha, and Greener Robert. 2007. “Is poverty or wealth driving HIV transmission?” AIDS 21:S5–S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardee Karen, Gay Jill, Croce-Galis Melanie, and Peltz Amelia. 2014. “Strengthening the enabling environment for women and girls: What is the evidence in social and structural approaches in the HIV response?” Journal of the International AIDS Society 17 (1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodder Sally L., Justman Jessica, Hughes James P., Wang Jing, Haley Danielle F., Adimora Adaora A., Del Rio Carlos, et al. 2013. “HIV acquisition among women from selected areas of the United States: A cohort study.” Annals of Internal Medicine 158 (1):10–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander Jocelyn A. 2004. “The social contexts of focus groups.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 33 (5):602–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hovmand Peter S., Andersen David F., Rouwette Etiënne, Richardson George P., Rux Krista, and Calhoun Annaliese. 2012. “Group model-building ‘scripts’ as a collaborative planning tool.” Systems Research and Behavioral Science 29 (2):179–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hovmand Peter S., Nelson Alissa, and Carson Ken. 2012. Understanding social determinants from the ground up. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 2012 International System Dynamics Conference, St. Gallen, Switzerland, July 22-26, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly-Hanku Angela, Kawage Thomas, Vallely Andrew, Mek Agnes, and Mathers Bradley. 2015. “Sex, violence and HIV on the inside: Cultures of violence, denial, gender inequality and homophobia negatively influence the health outcomes of those in closed settings.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 17 (8):990–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr Jelani C., Valois Robert F., Siddiqi Arjumand, Vanable Peter, and Carey Michael P.. 2015. “Neighborhood condition and geographic locale in assessing HIV/STI risk among African American adolescents.” AIDS & Behavior 19 (6):1005–13. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0868-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVeist Thomas A., Gaskin Darrell, and Richard Patrick. 2011. “Estimating the economic burden of racial health inequalities in the United States.” International Journal of Health Services 41 (2):231–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis Crystal Fuller, Rivera Alexis V., Crawford Natalie D., Gordon Kirsha, White Kellee, Vlahov David, and Galea Sandro. 2016. “Individual and neighborhood characteristics associated with HIV among Black and Latino adults who use drugs and unaware of their HIV-positive status, New York City, 2000–2004.” Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 3 (4):573–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S. 2013. “Inheritance of poverty or inheritance of place? The emerging consensus on neighborhoods and stratification.” Contemporary Sociology: A Journal of Reviews 42 (5):690–5. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell Joseph A. 2012. “Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach” In, edited by Bickman Leonard and Rog Debra J.. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Nunn Amy, Yolken Annajane, Cutler Blayne, Trooskin Stacey, Wilson Phill, Little Susan, and Mayer Kenneth. 2014. “Geography should not be destiny: Focusing HIV/AIDS implementation research and programs on microepidemics in US neighborhoods.” American Journal of Public Health 104 (5):775–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker Richard G., Easton Delia, and Klein Charles H.. 2000. “Structural barriers and facilitators in HIV prevention: A review of international research.” AIDS 14 (suppl1):S22–S32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philadelphia Department of Public Health. 2008. HIV and AIDS in the City of Philadelphia: Annual Surveillance Report. Philadelphia AIDS Activities Coordinating Office. Department of Public Health.

- Philadelphia Department of Public Health. 2016. “AIDS Activities Coordinating Office Surveillance Report, 2014.” City of Philadelphia, Accessed October 28. http://www.phila.gov/health/pdfs/2014%20Surveillance%20Report%20Final.pdf

- Prather Cynthia, Marshall Khiya, Courtenay-Quirk Cari, Williams Kim, Eke Agatha, O’Leary Ann, and Stratford Dale. 2012. “Addressing poverty and HIV using microenterprise: Findings from qualitative research to reduce risk among unemployed or underemployed African American women.” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 23 (3):1266–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond Henry F., Chen Y-H, Syme S. Leonard, Catalano Ralph, Hutson Malo A., and McFarland Willi. 2014. “The role of individual and neighborhood factors: HIV acquisition risk among high-risk populations in San Francisco.” AIDS & Behavior 18 (2):346–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes Tim, Singer Merrill, Bourgois Philippe, Friedman Samuel R., and Strathdee Steffanie A.. 2005. “The social structural production of HIV risk among injecting drug users.” Social Science & Medicine 61 (5):1026–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schensul Jean J., Berg Marlene J., and Nair Saritha. 2013. “Using Ethnography in Participatory Community Assessment” In Methods for Community Based Participatory Research in Health, edited by Israel Barbara A., Eng Eugenia, Shultz Amy J. and Parker Edith A.. New York: John Wiley (Jossey Bass). [Google Scholar]

- Schensul Stephen L.,Schensul Jean J., and LeCompte Margaret D.. 2012. Initiating Ethnographic Research. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press, Rowman and Littlfield. [Google Scholar]

- Smedley Brian. 2014. “Conceptual and methodological challenges for health disparities research and their policy implications.” Journal of Social Issues 70 (2):382–91. [Google Scholar]

- Smith Tanyka K., and Larson Elaine L.. 2015. “HIV sexual risk behavior in older Black women: A systematic review.” Women’s Health Issues 25 (1):63–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart Jennifer M. 2015. “A multi-level approach for promoting HIV testing within African American church settings.” AIDS Patient Care and STDs 29 (2):69–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumartojo Esther. 2000. “Structural factors in HIV prevention: Concepts, examples, and implications for research.” AIDS 14 (suppl 1):S3–S10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobias Barbara Q. 2001. “A descriptive study of the cultural mores and beliefs toward HIV/AIDS in Swaziland, Southern Africa.” International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling 23 (2):99–113. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2014. “Census 2000 Demographic Profile Highlights: Philadelphia City, Pennsylvania” Accessed September 14. http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/SAFFFacts?_event=&geo_id=16000US4260000&_geoContext=01000US%7C04000US42%7C16000US4260000&_street=&_county=philadelphia&_cityTown=philadelphia&_state=&_zip=&_lang=en&_sse=on&ActiveGeoDiv=&_useEV=&pctxt=fph&pgsl=160&_submenuId=factsheet_1&ds_name=ACS_2009_5YR_SAFF&_ci_nbr=null&qr_name=null®=null%3Anull&_keyword=&_industry=

- Walcott Melonie, Kempf Mirjam-Colette, Merlin Jessica S, and Turan Janet M. 2016. “Structural community factors and sub-optimal engagement in HIV care among low-income women in the Deep South of the USA.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 18 (6):682–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.