Abstract

LGBTQ youth are at increased risk of poor health outcomes. This qualitative study gathered data from LGBTQ adolescents regarding their communities and describes the resources they draw upon for support. We conducted 66 go-along interviews with diverse LGBTQ adolescents (mean age=16.6) in Minnesota, Massachusetts and British Columbia in 2014-2015, in which interviewers accompanied participants in their communities to better understand those contexts. Their responses were systematically organized and coded for common themes, reflecting levels of the social ecological model. Participants described resources at each level, emphasizing organizational, community and social factors such as LGBTQ youth organizations and events, media presence and visibility of LGBTQ adults. Numerous resources were identified, yet representative themes were highly consistent across locations, genders, orientations, racial/ethnic groups and city size. Findings suggest new avenues for research with LGBTQ youth and many opportunities for communities to create and expand resources and supports for this population.

Keywords: North America, qualitative research, adolescent health, sexual orientation, gender identity, community, social environment

A growing body of scientifically rigorous research with population-based samples of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and questioning/queer (LGBTQ) youth has consistently found these youth to be at significantly increased risk for multiple health risk behaviors and poor outcomes. LGBTQ youth are more likely than heterosexual, cisgender (i.e. non-transgender) youth to report smoking, alcohol consumption, illicit drug use, HIV risk behaviors, teen pregnancy, discrimination, violence victimization, depression, and suicidal ideation and attempts (Coker, Austin, & Schuster, 2010; Corliss et al., 2010, 2012; Corliss, Rosario, Wypij, Fisher, & Austin, 2008; Eisenberg & Resnick, 2006; Eisenberg, 2001; Haas et al., 2011; Herrick, Marshal, Smith, Sucato, & Stall, 2011; Institute of Medicine, 2011; Marshal et al., 2011; Saewyc et al., 2006, 2007; Saewyc, Poon, Homma, & Skay, 2008). Meyer’s Minority Stress Theory (2003) explains these disparities as resulting from unique stressors (e.g. discrimination, stigma) stemming from a marginalized identity. These stressors can act on individual well-being through expectations of rejection, concealment, internalized homophobia and other mechanisms, particularly in the domain of mental health.

It is important to note, however, that even though risk may be elevated, most LGBTQ adolescents are well-adjusted and do not experience the problems faced by some of their peers. The Minority Stress Theory includes a construct of coping and social support, which may buffer the ill-effects of stressors and contribute to positive health outcomes (Meyer, 2003). Understanding the strengths and supports LGBTQ youth draw from is crucial to the development and expansion of resources, programs and systems to help others in this population and promote healthy coping with minority-related stress. Social ecological theoretical frameworks can be overlaid on the concept of coping and social support. These frameworks posit that a wide variety of protective factors at the interpersonal (e.g. friend, family, peer interactions), organizational (e.g. school programs, health clinics), community (e.g., student health coalitions, national education organizations), and societal levels (e.g. policies, social norms, media messages) contribute to individuals’ well-being (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler, & Glanz, 1988; Sallis & Owen, 2002). Importantly, social ecological models also maintain that factors at each level can not only act directly on individuals, their health behaviors and well-being but can also act indirectly, by interacting with factors at other levels of the model. These cross-level influences can multiply or dampen the effect on the individual.

In the field of LGBTQ youth health, burgeoning interest in broader structural factors such as organizational characteristics has led to important findings about the protective effects of inclusive education, gay-straight alliances (GSAs) and anti-bullying policies in schools (Birkett, Espelage, & Koenig, 2009; Blake et al., 2001; Coulter et al., 2016; GLSEN, 2011; Goodenow, Szalacha, & Westheimer, 2006; Hatzenbuehler, Birkett, Van Wagenen, & Meyer, 2014; Heck, Flentje, & Cochran, 2011; Kosciw, Greytak, & Diaz, 2009; Toomey, Ryan, Diaz, & Russell, 2011), for example, suggesting that young people can glean critical support from these institutions. Characteristics of the broader community have also been shown to be similarly protective for youth. Research has found that various indicators of the social climate for LGBTQ populations such as rural location, religious composition, concentration of same-sex couples, political party affiliations, and policies regarding hate crimes and employment discrimination are associated with risk behaviors among LGB youth (Hatzenbuehler, Jun, Corliss, & Austin, 2014; Hatzenbuehler, Jun, Corliss, & Bryn Austin, 2015; Hatzenbuehler, Pachankis, & Wolff, 2012; Hatzenbuehler, 2011; Kosciw, Palmer, & Kull, 2015; Poon & Saewyc, 2009). This work has identified important avenues for policy change and other supports. However, the literature at this stage is almost entirely quantitative in nature, and measures were developed without extensive input from LGBTQ young people themselves. Qualitative research with LGBTQ adolescents has the potential to uncover new indicators of support from the perspective of these young people. This expansion in scope can add new knowledge regarding the most salient and specific protective factors for this population beyond what is already known about supportive school and community characteristics.

The current study used qualitative methods to gain insights from LGBTQ adolescents about their communities, and findings describe resources and supports in their communities as well as what additional resources they wish were available to them. Insights obtained directly from youth will provide rich information about the types of supports they experience as helpful, or not helpful, contributing to further identification and development of organizational- and community-level protective factors.

Methods

Recruitment and Sample

Project RESPEQT (Research and Education on Supportive and Protective Environments for Queer Teens) is a mixed methods, multisite study of social influences on the health and well-being of LGBTQ youth. Sixty-six LGBTQ-identified adolescents ages 14-19 years (mean age = 16.6, standard deviation = 1.4) were recruited from a variety of locations in Minnesota (n = 24) and Massachusetts (n = 19) in the USA, and British Columbia, a western province of Canada (n = 23). Recruitment was aided by LGBTQ community organization staff in each location and involved sharing study information with youth or youth-serving professionals in organizations, schools and at community events, and inviting participation. Strategies included distributing fliers at community spaces or group meetings, speaking at group meetings, distributing materials at large events, and word of mouth. Participants were encouraged to have interested friends contact the study team.

Young people who contacted the study to express interest in participating were screened for sexual orientation and gender identity (eligibility included identifying as LGBTQ and age between 14 and 19 years), and arrangements were made to conduct the interview. In Minnesota, minors were asked if they were comfortable with study staff contacting their parents for consent, as required by that University’s Institutional Review Board. Participants were comfortable having a parent contacted in all but one case (in which parental consent was waived), and parental consent was obtained by phone, email or in person at the start of the interview. Participants provided their own assent/consent in the other two locations. Additional details of the recruitment and intake process are available elsewhere (Porta et al., 2017). Institutional Review Boards at the University of British Columbia, the University of Minnesota and San Diego State University (for data collection in Massachusetts) approved all study protocols used in their own location (with variations as described).

Participants described their sexual orientation and gender identity with a wide range of terms, summarized in Table 1. Approximately one-third self-identified as female, one-third as male and one-third as transgender or related labels (e.g., genderqueer, non-binary); participants were similarly distributed across sexual orientation labels, including gay/lesbian, bisexual and queer or other labels (e.g. pansexual, rainbow sexual). Slightly more than half identified as White or European ancestry (only), about a quarter reported a mixed ethnic background, and other participants identified as Latino, Aboriginal/Native American, African/African American, Asian, or Middle Eastern. Participants were diverse with regards to their geographic demographics as well: 19 came from urban settings, 22 from suburban, 9 from smaller cities and 16 from rural locations across the three sites.

Table 1.

Self-descriptors of sexual orientation and gender identity among participants interviewed for Project RESPEQT (N=66)

| Female n |

Male N |

Trans and additional labelsˆ n |

TOTAL N |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gay or Lesbian` | 8 | 13 | 3 | 24 |

| Bisexual` | 8 | 10 | 3 | 21 |

| Queer and additional labels~ | 5 | 1 | 13 | 19 |

| Straight and other* | - | - | 2 | 2 |

| TOTAL | 21 | 24 | 21 | 66 |

“gay or lesbian” includes n=2 “same-sex attraction;” “bisexual” includes n=1 “bicurious”

“trans” included n=11 whose self-descriptor included “trans” (e.g. “trans-female,” “non-binary trans person”; additional descriptors included n=10 who provided various labels, e.g. “genderqueer,” “fluid,” “non-binary” or “neutral”

n=9 “queer;” additional descriptors included n=7 “pansexual,” n=1 “asexual,” n=1 “panromantic asexual” and n=1 “rainbow sexual”

n=1 “straight” and n=1 “other”

Go-along Interviews

Research methods that give voice to young people can elicit information regarding the meanings ascribed to experiences and important mechanisms of action (Morse & Field, 1995). Indeed, open-ended data collection methods are well-suited to contextualizing perceptions and experiences. Go-along interviews in particular, in which the participant and interviewer move through the participant’s “action space” as part of the interview (Carpiano, 2009; Cummins, Curtis, Diez-Roux, & Macintyre, 2007), have the advantage of obtaining young people’s responses to what they encounter while they are in the setting of interest. Visual cues in the environment are likely to prompt comments or insights that might not be triggered in a stationary interview (Garcia, Eisenberg, Frerich, Lechner, & Lust, 2012). This data collection method is particularly suitable for research questions addressing social and community factors that may protect LGBTQ young people from stigma, harassment and health-jeopardizing behaviors and promote positive youth development.

Interviewers were six relatively young, female-identified graduate students, including two who identified as queer or lesbian. Each conducted interviews in her own study location to ensure some familiarity with the region. Interview staff were hired based on their respectful awareness and demonstrated experience and capabilities working with LGBTQ young people. All interviewers had prior experience working with LGBTQ youth and were knowledgeable about the LGBTQ community. Interviews began at a location of the participant’s choosing and proceeded by car (n = 22) or public transportation and/or on foot (n = 36); 8 participants chose to remain in a single location. The distance covered during an interview ranged from under one mile to over 30 miles, depending in part on the type of transportation used.

A series of open-ended questions were used to guide the interview, including “If an LGBT friend came to visit you here in your town, where would you recommend they go to have fun or to hang out?” and “If an LGBT friend was visiting you here and needed help with something or had a problem, where would you recommend they go to get care or support?” The interviewer and participant would then visit these places as desired by the participant. Probes and follow-up questions were used to draw out additional information on characteristics of each place that made them feel safe or were fun, welcoming or supportive. Participants were also asked to describe resources they wished were available in their area but were not, particularly in locations with few supportive or welcoming places. At the conclusion of each interview, participants were asked to identify the most important supports and resources they had described or visited.

Interviews took 78 minutes, on average (range = 35-110), and all were audio recorded. Participants received $40-$50 gift cards to a major retailer in appreciation for their shared time and insights (amounts varied by location). Shortly after the interviews, interviewers completed reflective journaling to capture observations about the environment and the interview experience, non-verbal cues observed and other notes.

Data Analysis

Audio recordings were professionally transcribed; full transcripts were reviewed with the audio by the original interviewer to correct any errors. All potential identifiers (names, specific locations) were removed to preserve confidentiality during the analysis process. Research team members involved in the analysis were diverse with regards to gender, age group, sexual orientation, academic level (students, post-doctoral fellows, faculty) and professional discipline (including public health, nursing, psychology, social work, anthropology and family social science), and represented all three study locations.

The goal of the analysis was to organize participant comments, identify overarching themes, and describe thematically organized resources and supports mentioned by LGBTQ youth. In the first stage, the team coded transcripts (i.e., assigned descriptive labels to sections of text) using atlas.ti, software and arrived at consensus on a set of broad descriptive codes, using a quasi-deductive approach (Miles & Huberman, 1994). All transcripts were coded independently by two coders; numerous rich discussions ensued to examine coding decisions in the context of the team members’ subjective experiences. Discrepancies were discussed to resolution with team members from across study sites, which was a rigorous in-depth process that contributed to the trustworthiness of the resultant coded data (Rolfe, 2006). The research team also used interviewers’ reflective journaling and memo-ing during analytic coding to enhance the analysis. This process of reflection and discourse strengthened researchers’ confidence in the coding scheme, coding assignments, and thematic interpretations.

For the present paper, we selected first-level codes describing resources for further analysis (e.g. “events,” “services,” “activities”). We read through quotes within each code, using the previously stated research questions to organize the data descriptively into broader themes that aligned with levels of the social ecological model. Through this theory-driven iterative process, we identified the most salient themes across codes related to resources or lack-thereof; these are described below.

Results

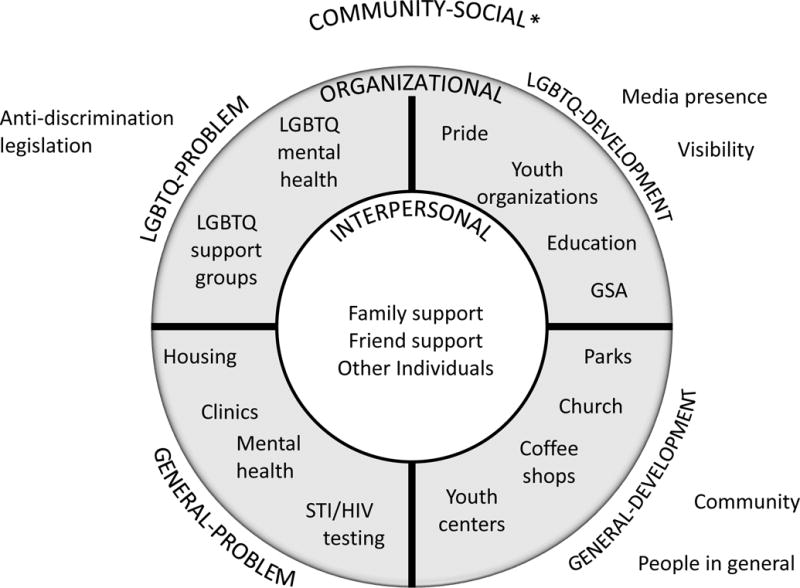

All the youth described resources, supports and needs that they perceived in their respective communities. General themes were consistent across locations, genders, orientations, racial/ethnic groups and city size. Although some differences were noted – for example, an urban participant’s favorite resource might be identified as a need by a youth in a smaller city – the types of organizations, resources and supports that participants brought up were similar across demographic categories. These can readily be mapped onto the overarching framework of the social ecological model, including assets in interpersonal relationships, organizational supports, and characteristics of the community or larger social environment. In keeping with this theoretical model, factors at any level can act directly on individuals, their behaviors and well-being; yet can also act on factors at other levels for a combined effect on the individual. Several resources mentioned by youth exemplify the interactions of multilevel factors. The multiple levels of resources represent the dominant theme of the findings.

Two additional sub-themes further characterize resources at the organizational level, and to a lesser extent the community/social level. The first is the population targeted by any particular resource, which was typically either LGBTQ-specific or the general population. The second is the organization’s overall orientation towards problem management (e.g. bullying prevention program) or general adolescent development (e.g. after school sports program). Themes and sub-themes are graphically summarized in a “Life Preserver” model, depicted in Figure 1. As an application of the social ecological model specifically for LGBTQ youth, it includes an inner, middle, and outer layer, representing interpersonal, organizational and community-social levels of influence. Quadrants distinguishing population and orientation characteristics further detail the organizational level. Results are described below, with illustrative quotes from participants (descriptors noted in parentheses).

Figure 1.

LGBTQ “Life Preserver” of resources

The Social Ecological Model: Interpersonal Level

Interpersonal supports were identified as “most important” resources by almost half of participants, with an emphasis on friends and family. For example, “my parents, my family, my friends. If they accept me, I don’t care about strangers. I don’t care about my workplace. I don’t care about the school. If the people close to me accept me, I can make it through life” (bisexual, female, Aboriginal/European, rural, age 17, British Columbia). Many participants also commented on peers, teachers or other individuals being tolerant, non-judgmental and accepting. In particular, using preferred pronouns was seen as an indicator of support on an interpersonal level. One youth commented:

If you’re all chatting, the first thing they do is ask you your preferred pronouns, just so, like, know everyone’s gender is respected…. It’s really small … But it makes such a big difference because you feel like you don’t have to repeatedly come out. (pansexual, female, European, urban, age 16; British Columbia)

Use of preferred pronouns is an example of a factor at the interpersonal level affecting – and being affected by – other ecological levels as well as the individual youth who experiences support directly. Organizational meetings that include preferred pronouns as part of routine introductions, for example, prompt these interpersonal exchanges and signal to youth that their gender identity is supported. Likewise, routinely discussing preferred pronouns can serve to normalize these conversations even beyond the organization and create a climate of awareness and acceptance of gender variant youth among cisgender youth as well.

The Social Ecological Model: Organizational Level

The focus of interview questions, and therefore the largest category of resources described by participants, reflects organizational and institutional supports. These included events, LGBTQ youth-serving organizations, casual spaces, GSAs and others. Most resources at this level could also be categorized with regards to the targeted population (LGBTQ or general) and the orientation of the service (problem or youth development).

LGBTQ-specific vs. general population

LGBTQ youth described many spaces, activities and supports that were designed specifically for LGBTQ people, to provide safety, services, tailored information and a sense of community. Although these are organizational factors, one clear reason for their importance was facilitation of supportive interpersonal interactions and relationships, again demonstrating the cross-level features of the social ecological model.

For many youth, major events such as Pride festivals or parades were a primary example of community support:

Especially the Pride parade. That’s a really empowering event. A lot of people come. Even non-LGBT people are on the sidelines and supportive, like, ‘You go!’ It’s definitely empowering. I feel like that’s one day when everyone in the LGBT community can come together and be themselves: the people who like to dress in drag, transgender people, gay, bisexual, asexual, all those. (gay, male, white/Hispanic, suburban, age 17, Massachusetts)

Although Pride activities were the largest and most commonly cited, events such as Youth Pride, LGBTQ youth conferences or LGBTQ youth social events (e.g. “gay prom”) held a similar importance for many participants.

Youth focused on LGBTQ youth-serving organizations as a critical source of support. These agencies provided access to similar peers, support groups, mental health services, sexual health services and access to safe housing, among other needs. One participant described some of the benefits of a suburban youth group:

It is designed for LGBTQ youth to go to to feel safe, to have a place they can hang out and feel like they don’t have to worry about everyone judging them.

Interviewer: What happens in that space that makes you feel safe?

Knowing that I’m surrounded by people that are somewhat similar to me. And also knowing that there are people that will help me through really rough times and also knowing that there’s people that will tell me how it is straight up. If I’m being a bitch they’re going to tell me I’m being a bitch. (rainbow sexual, Aboriginal/European/Asian/Black, suburban, age 18, British Columbia)

In addition to the freedom from discrimination and harassment youth experienced in these spaces, staff competency in working with the LGBTQ youth population was particularly valued by participants who described these organizations as a source of support.

Gay/Straight Alliances (GSAs) at school were a subset of LGBTQ youth-serving organizations that were distinguished by their association with schools, allowing for connection with supportive peers and adults who were consistently and easily accessible (in contrast to a drop-in center that might be visited less frequently or have a rotating staff). GSAs were often seen as a significant source of support for LGBTQ youth, meeting a need that was not available in the community more broadly. When asked where they might take an LGBTQ friend in need of support, one participant responded:

I think I’d take them to the school… because really the [GSA] is the only thing that I know of, and it’s really supportive…. If someone comes in and they have a problem we’re, like, all right. Come here and we’ll comfort you. (pansexual, trans, European, rural, age 17, British Columbia)

Because of their affiliation with the school, GSAs could reflect the institution more broadly, suggesting a variety of resources that were not designed specifically for LGBTQ youth but nonetheless had the potential to provide important support to this population. Many youth commented on schools, describing supportive teachers, counselors and staff, and programs such as anti-bullying initiatives. However, youth also shared many negative experiences and perceptions about their schools, including harassment and hostility, as well as support programs that failed to meet their promise. For example, “They post safe space [signs] all over, but there’s no fucking safe space, honestly…. That’s all I know. There’s just no safe space. Maybe for gay people, but trans? No” (straight, trans, mixed race/ethnicity, suburban, age 16, Minnesota). Comments from participants, including negative experiences, point to the potential of schools to provide a safe haven for LGBTQ youth, even though their primary mission is education for young people in general.

Participants described many other organized activities and groups that were not LGBTQ-oriented, but were safe and welcoming places for them, such as arts activities (e.g. art, dance, theater, slam poetry), social justice groups and volunteering. These general population groups were supportive of LGBTQ youth in three ways. First, many LGBTQ youth gravitated towards certain activities, providing a sense of community and connection for young people. For example, several acknowledged the stereotype of drama clubs attracting LGBTQ youth, and said that was consistent with their own experience. Second, certain clubs or groups drew non-LGBTQ participants who were especially welcoming and supportive of diversity. One queer youth from Minnesota described their dance community as “radically inclusive”; another young person shared, “There’s an anime club, which I’ve experienced and it’s really positive. Everyone is, I guess you could say weird or something like that” (bisexual, female/trans, white, suburban, age 16, Minnesota). In both these ways, general groups and organizations can affect the interpersonal social ecological level by increasing opportunities for supportive relationships, in addition to being a resource as a group. Third, organizations or activities used certain practices that indicated they were sensitive to a range of experiences and identities, such as issuing trigger warnings (i.e., an alert of potentially upsetting content) before a poetry slam, or eschewing traditional gender norms in a dance program:

I took [swing dancing] lessons for a little while… it wasn’t, like, oh, the men lead, the women follow. It’s like… people who want to learn to lead and people who want to learn to follow. And that was really nice… it was all, like, gender mixed. (pansexual, female, European, urban, age 16, British Columbia)

Youth also mentioned a wide variety of casual spaces that were intended for use by the general public, yet were viewed as resources by LGBTQ adolescents in their specific community. Coffee shops, parks and outdoor spaces, community centers, malls and specific stores and restaurants were among the places participants described feeling accepted and welcome, even in the absence of any formal mission related to the LGBTQ community. For example, one young person noted, “Everybody is relaxed, because you know, coffee shops are like that. Everybody’s just coming here because they’re tired and they need coffee, and they’re not going to judge you.” (pansexual, male, white, small-medium town, age 18, Minnesota). Another described a restaurant:

There’s also a little burrito place by my house…. And it’s really lovely in there and all the people at the counter are really rad and always friendly and chatting to you. And I can tell it’s a nice environment ‘cause they have the LGBT newspaper and they always stock it. It’s just nice. (pansexual, female, European, urban, age 16, British Columbia)

Churches were the focus of many participant comments, including the church as an institution, as well as specific churches with which participants had personal experience, noting the difference between the two. A participant shared, “Usually, when you associate Christianity, you associate [it] with the negative aspects, but it’s important to know that like with anything, there’s always an oasis from all the bad things happening” (lesbian, female, suburban, white, age 16, Massachusetts). Although comments about “the church” were consistently negative, personal experiences were mixed. Some described how their own religious community was not supportive or welcoming; for example, a young adult shared, “that’s my old church, but I was excommunicated basically” (gay, male, suburban, white, age 18, Minnesota). However, as with schools, several comments indicated that their church had become a safe and inclusive space:

When we got in the church, I was like, oh, it’s a church, and I was just hoping … I was unsure if the people who go to this church would be okay with us being in the basement, and I was surprised to see that there was a rainbow sticker at the church. It was the first time I’ve ever seen a rainbow sticker at a church. I felt really unsure if I was going to be accepted here, until the second time I started going, and I was like, oh, people here are really accepting (bisexual, “it,” Native American, small-medium city, age 18, Minnesota).

Participants described welcoming clergy, LGBTQ-specific activities hosted on-site, or congregational values as examples of how certain churches demonstrated their inclusivity and could be a valuable resource to young people seeking a faith community.

Problem focused vs. general adolescent development orientation

Often, youth-serving organizations centered on crises or problems frequently faced by LGBTQ youth. Such “problem-focused supports” included mental health services, sexual health care (e.g. HIV testing, condom provision), support groups and housing and food assistance. Many young people knew of these resources even if they had not personally needed to utilize them. One commented:

It’s specifically for LGBT youth… They give you free food, and they have trained people, advisors there, trained to deal with LGBT issues. It’s pretty great. There’s a sign-in, too. You sign in your name, and there are questions like “are you homeless?” and “do you have somewhere to stay?” so I assume they deal with it if you don’t have anywhere to stay, which is really good. (bisexual, trans/non-binary, white, rural, age 18, Massachusetts)

At the other end of the spectrum, many resources provided general support for adolescent development – “teens being teens” – in a positive and affirming space or provided enrichment or leadership opportunities in a safe context. This included having a comfortable place to spend time with peers, as well as activities to allow young people to learn and grow in a supportive environment (“It’s just friendly things, just to basically hang out. They have talent shows and poetry readings and all that” (lesbian, female, French Caribbean, small-med city, age 16, Massachusetts)). Youth also spoke of opportunities for leadership development through an LGBTQ organization, which was not as accessible to them in their school or other community location. One young person described his introduction to an LGBTQ youth organization, and leadership opportunities, like this, “They had an ice cream social two Junes ago, and I went…. It was pretty cool and fun, and they had applications to be a peer leader, so I signed up. That’s what happened” (gay, male, white/Hispanic, suburban, age 17, Massachusetts). Youth described similar opportunities through their GSAs or other LGBTQ-focused advocacy organizations.

Interestingly, some resources successfully merged problem-focused resources and general adolescent development resources. In describing a large, metropolitan LGBTQ youth serving organization, one participant drew out both aspects:

Because they have fun staff, young staff, they blend in perfectly with who I am and what I am. They have a Wii, so we do Wii games and we dance, we sing. It feels like you’re in someone’s living room, almost, and just hanging out. That’s exactly what [the organization] feels like to me. They do HIV testing, and they have condoms everywhere. It’s awesome. (lesbian, female, Native American/Black, urban, age 18, Massachusetts)

Additional organizational resources

Youth identified LGBTQ-relevant education as an organizational characteristic that could be a support, and this was most commonly described as a need rather than an existing resource. Some students described a need for sexual health education materials that included non-heterosexual issues and examples; others talked about the school’s or the GSA’s role in educating other students about sexual orientation and gender identity in order to “normalize” these diversities and reduce stigma. For example, one participant described a potential class addressing this issue:

I guess teaching people about different sexual orientations or romantic orientations and the difference between them, and then gender identities, and awareness for different gender identities, and also acknowledging more people, and saying why it’s totally natural and normal to be these things and it’s just something that we are. (asexual, male/trans, suburban, white, age 17, Minnesota)

This particular role of schools or GSAs provides another example of how levels act upon one another. Specifically, in addition to being a function of the organization, one goal of this type of education is to change perceptions about LGBTQ people in the population in general, thereby affecting the community or societal sphere.

An organizational feature described by participants was the need for visual cues and information about existing resources, to indicate that the location would indeed be welcoming and supportive, particularly for general community settings not specifically targeting LGBTQ audiences. One participant commented, “There’s also something downstairs that isn’t open…. it’s a little co-op café that we have that’s extremely queer friendly. I wish you could see it. There’s rainbow flags and queer pictures” (queer, female, Black/Hispanic, suburban, age 18, Massachusetts). Without such outward signals or other information to identify a space as “queer friendly,” it was more difficult for youth to find important resources. Visible symbols also spoke to the broader climate of the community in which the organization was located. Where supportive organizations had no public visibility, it reflected a general climate that was less supportive of LGBTQ populations, again demonstrating interactions among levels in the social ecological model.

The Social Ecological Model: Community/Social level

Participants also described several relational and role-modeling resources at the community or social level. The presence of LGBTQ adults was noted by participants, specifically the visibility of others who were “out” and therefore able to be role models to younger people. Youth mentioned people in their communities as well as celebrities visible in the media; both served to normalize LGBTQ identities and change public perceptions of this group. Furthermore, they could demonstrate the possibility of a happy, healthy and productive adulthood. For example:

It’s so cool to just have different options presented. It’s important to have someone exemplify a way to live your life and that it’s okay to be gay, or you can be a dancer, or you can own a restaurant…. You can be a man and be a good cook; you can be whatever. You need someone to show you how to do it somehow. (queer, fluid, urban, white, age18, Minnesota)

As with organizational resources, visible LGBTQ adults could also be conceptualized according to our two sub-themes, in that they were LGBTQ-specific (rather than general population) and supported general development (rather than specific problems), as shown in Figure 1.

Several participants also commented on “people in general” in their community (aside from their immediate friends and family), and ways these people could show their supportiveness and make participants feel welcome and accepted. One young adult responded to a question about the most important thing that makes a place feel safe and supportive, “The people are what make me feel safe and supported… Everyone in my shop wearing pins and stuff like that, where they show their support, which is nice” (lesbian, female, white, small-med city, age 18, Massachusetts). Such resources – supportive people and community members – would be categorized as general population resources that support youth development broadly.

Cross-cutting Example: Gender Neutral Bathrooms

Gender-neutral bathrooms were mentioned by many participants as a particularly noteworthy resource, including by those who did not identify themselves as gender variant Interestingly, this resource can be categorized on more than one level of the social ecological framework. The conversation shown in Box 1 exemplifies numerous comments regarding ways in which gender-neutral bathrooms provide support at an interpersonal level (e.g. the absence of harassment), yet also reflect an organizational commitment of resources to create a welcoming atmosphere with single-occupant bathrooms. This commitment could be a relatively minor investment in gender-neutral signage, or could be quite substantial, resulting from pro-active space planning or costly renovation. Unlike examples provided above, this resource does not only affect other levels of the social ecological model (e.g. by creating a social climate that is more inclusive), but is itself an example of a protective resource operating at two levels. Gender-neutral bathrooms also transcended the two sub-themes, in that they are a particularly useful resource for LGBTQ populations and are often designed with them in mind, but can be used equally by anyone. In this way, gender-neutral bathrooms also protect against the common problem of harassment, yet are still part of the everyday human experience.

Box 1. An example of gender-neutral bathrooms.

Respondent: The only supportive place that seems really geared towards teens could be [Informal Community Resource 1MN], I think. They have things on the wall that make it pretty obvious that it’s a queer-friendly place. Their bathrooms are gender-neutral, so there’s no fear of being stared at or yelled at in a bathroom, which is surprisingly common, I guess.

Interviewer: Really? Have you had experiences like that?

R: Yes. I’ve been, I guess, stared at in women’s restrooms, like I’m a creepy guy who’s just lurking. When I was a little kid, it’d be like, ‘Buddy, get out of this restroom. You’re in the wrong bathroom.’ Yeah.

I: So, gender-neutral bathrooms make a place feel safer.

R: Yeah. It’s stressful using a bathroom. Just in general it’s a stressful experience, but when it’s a gender-neutral bathroom, it’s really nice.

I: That sounds like really important to have in places so you’re not stressed out when you’re just trying to use the bathroom.

R: Yeah, and just the fact that it says ‘gender-neutral,’ too, you know it’s a welcoming place, that you’re not going to be judged.

I: Are you saying that, as opposed to a place that would just have a bathroom sign that has a female-male symbol on it? Like, there is something about…

R: Yeah. That’s what also is really cool: just no stress; it’s just a bathroom. But it’s cool to know, too, that they consciously made them gender-neutral. It just makes it even more of a welcoming place.

(lesbian, female, urban, white, age 17, Minnesota)

Discussion

LGBTQ adolescents identified many different kinds of resources and supports in their communities, and themes were consistent across demographic categories. Examples came from across the social ecological model and included those that are LGBTQ-focused and more general and those that are problem-focused as well as for general adolescent development. Together, these resources can be represented as a “life preserver” supporting LGBTQ youth. For those facing the greatest challenges, the presence of strong supports could literally be life-saving; for LGBTQ youth with greater internal or interpersonal assets, this life preserver may simply provide additional buoyancy for their continued development. Given the different needs youth have, it was unsurprising that responses regarding resources varied widely. Importantly, resources and supports included many “obvious” responses, such as LGBTQ youth serving organizations and sexual health services, but participants also noted many examples of resources not explicitly aimed at LGBTQ adolescents or common issues that arise in this population but were nevertheless important supports (e.g. coffee shops). Taken together, findings suggest many opportunities for communities to provide resources and support to LGBTQ young people.

In several cases participants’ responses focused on negatives, such as unwelcoming churches or unsupportive schools. However, within each of these categories there were also examples of how that same type of space could be positive and supportive. Even places that might seem to be very unlikely resources for LGBTQ youth (e.g. a Catholic church) were mentioned by some in our sample as helpful, comfortable and safe. This suggests that almost any type of space or organization has the potential to provide support for LGBTQ youth. Using visual cues such as rainbow flags or stickers can outwardly indicate a supportive environment, which must then be backed by genuine respect for, sensitivity to and understanding of the needs of LGBTQ populations (Wolowic, Heston, Saewyc, Porta, & Eisenberg, 2016).

Building Up Resources at Each Level

A paradox of the social ecological model is that the strength of influence of each level operates inversely with the number of people affected. For example, a loving and supportive parent (interpersonal level) has a profound impact on the development of their own children, whereas an outspoken celebrity (community-social level) might have a small impact on a very large number of youth. This consideration is important in the development of resources for LGBTQ youth at each level of the model.

Interpersonal supports, described by almost all youth, are critically important and powerful resources. However, these resources are specific to each individual and change in this domain may require tailored solutions at the level of each individual, one case at a time. Programs and organizations such as PFLAG facilitate change by bolstering and supporting interpersonal relationships for LGBTQ young people (PFLAG, n.d.). Likewise, mentoring programs similar to Big Brothers/Big Sisters match mentors with LGBTQ youth, providing critical interpersonal resources (True Colors, n.d.). As with resources themselves, intervening on resources can also cross levels of the social ecological model. For example, the large-scale social marketing used to advance policy around same-sex marriage in the U.S. included sharing personal stories that were effective in changing hearts and minds, likely resulting in increased support for LGBTQ youth in previously unaccepting families.

Organizational and institutional resources across all quadrants were most commonly mentioned by participants. Resources at this level affect many people in clear and meaningful ways and are amenable to programs and interventions on a manageable scale (e.g. programs in the school, development of youth organization). Youth organizations, friendly coffee shops, housing assistance and LGBTQ mental health services are examples of resources that can keep young people afloat through times of crisis or challenge or support them more generically in their personal development. As described above, certain resources at this level (e.g. educational programs), can also act upon the interpersonal or the community-social levels, which can then magnify their intensity (through affecting interpersonal exchanges) or scope (through changing the social landscape for a larger number of people). At the organizational level in particular, the life preserver model can be a useful tool for advocates, health care providers, parents and youth in communities. It can guide assessment of resources in a community, identifying shortcomings, and determining where additional resources could be developed or expanded to create a robust system of supports for LGBTQ youth.

The outermost area of Figure 1 represents community support and social climate. Study participants identified many of these relatively abstract concepts. Additional resources such as comprehensive health care policy (general-problem) and funding for health disparities research (LGBTQ-problem) are examples of further possible supports that were not raised by youth, who were perhaps too far removed from this adult-focused public policy discourse, or did not feel its relevance to their lives as LGBTQ youth. Changes at this level, e.g. through public policy, have the potential to act upon many individuals throughout a community or social group yet are the most difficult to influence, requiring, in many cases, significant financial investment or political will. However, the past decade has seen considerable social change with regards to public attitudes about sexual orientation (Pew Research Center, n.d.), built on carefully crafted messages and social movements. Continued growth at this level is feasible through combined efforts and creates a backdrop of support for LGBTQ youth in their own lives.

Limitations and Strengths

Results of this study need to be viewed in light of some limitations. Specifically, the requirement of parental consent in one location may have precluded involvement of some adolescents, such as those who were not out to parents (Mustanski, 2011). In addition, although youth visited many resources, some were not visited due to business hours, location, or participant preference, among other factors. Finally, because our recruitment strategy relied largely on partnerships with LGBTQ-youth serving organizations and GSAs, we were more likely to reach young people who were out to peers and family. This work may therefore not fully capture the experiences of those who have not disclosed their sexual orientation or who are not affiliated with LGBTQ youth organizations.

In spite of these limitations, the go-along method was particularly well-suited to the research questions about community resources and is a strength of this investigation. The focus on adolescents is an additional strength because historically studies have focused on LGBTQ young adults due to the challenges associated with conducting research with this age group (Mustanski, 2011). Furthermore, the sample included a large number of participants across three locations, with ample diversity with regards to sexual orientation, gender identity, race/ethnicity and geographic setting. This diversity engendered confidence that we have adequately captured the viewpoints of a range of LGBTQ adolescents on this topic.

Implications for Research and Practice

In studies of how features of organizations and communities are associated with the health and well-being of LGBTQ youth, it is important to consider resources beyond those that have been included in previous quantitative research (e.g. presence of same-sex couples, hate crimes legislation, (Hatzenbuehler, Jun, et al., 2014; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2015, 2012; Hatzenbuehler, 2011; Poon & Saewyc, 2009), and to incorporate a youth perspective. While such organizational and community characteristics have been shown to be protective for LGBTQ populations, other characteristics, such as the nature, density or focus of supportive resources, may be important – and actionable – contributors.

In the general community and within the LGBTQ support sector, agencies and professionals are often “silo-ed” with separate missions and activities, yet cognizance and coordination can strengthen the overall network of resources, services and supports. Youth are better positioned to thrive when protective factors exist in every socio-ecological layer and within each quadrant of the Life Preserver model. The LGBTQ youth in our study demonstrated awareness and sensitivity to proximal and distal resources and supports in their lives, as well as the absence of these resources. Numerous professionals working with or on behalf of youth are well-positioned to give attention to resources – and deficits – at a variety of levels so as to ensure LGBTQ youth have supports available to them, not only in “problem-focused” agencies but in broader systems that encourage healthy adolescent development.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HD078470. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Alderson K. The Ecological Model of Gay Male Identity. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 2003;12(2):75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Birkett M, Espelage DL, Koenig B. LGB and questioning students in schools: the moderating effects of homophobic bullying and school climate on negative outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38(7):989–1000. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9389-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake SM, Ledsky R, Lehman T, Goodenow CS, Sawyer R, Hack T. Preventing sexual risk behaviors among gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents: the benefits of gay-sensitive HIV instruction in schools. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(6):940–946. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Carpiano RM. Come take a walk with me: the “go-along” interview as a novel method for studying the implications of place for health and well-being. Health & Place. 2009;15(1):263–72. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker TR, Austin SB, Schuster MA. The health and health care of lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents. Annual Review of Public Health. 2010;31:457–77. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corliss HL, Rosario M, Wypij D, Fisher LB, Austin SB. Sexual Orientation Disparities in Longitudinal Alcohol Use Patterns Among Adolescents. 2008;162(11):1071–1078. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.11.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corliss HL, Rosario M, Wypij D, Wylie SA, Frazier AL, Austin SB. Sexual orientation and drug use in a longitudinal cohort study of U.S. adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(5):517–21. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corliss HL, Wadler B, Jun H, Rosario M, Wypij D, Frazier A, Austin SB. Sexual-Orientation Disparities in Cigarette Smoking in a Longitudinal Cohort Study of Adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012 doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Coulter R, Birkett M, Corliss HL, Hatzenbuehler ML, Mustanski B, Stall RD. Associations between LGBTQ-affirmative school climate and adolescent drinking behaviors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;161:340–347. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins S, Curtis S, Diez-Roux AV, Macintyre S. Understanding and representing “place” in health research: a relational approach. Social Science & Medicine (1982) 2007;65(9):1825–38. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME. Differences in Sexual Risk Behaviors between College Students with Same-Sex and Opposite-Sex Experiences: Results from a National Survey. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2001;30(6):575–589. doi: 10.1023/a:1011958816438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME, Resnick MD. Suicidality among gay, lesbian and bisexual youth: the role of protective factors. The Journal of Adolescent Health : Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2006;39(5):662–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia CM, Eisenberg ME, Frerich EA, Lechner KE, Lust K. Conducting go-along interviews to understand context and promote health. Qualitative Health Research. 2012;22(10):1395–1403. doi: 10.1177/1049732312452936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GLSEN. The 2011 National School Climate Survey 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Goodenow CS, Szalacha L, Westheimer K. School support groups, other school factors, and the safety of sexual minority adolescents. Psychology in the Schools. 2006;43(5):573–589. [Google Scholar]

- Haas AP, Eliason M, Mays VM, Mathy RM, Cochran SD, D’Augelli AR, Clayton PJ. Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: review and recommendations. Journal of Homosexuality. 2011;58(1):10–51. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2011.534038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. The social environment and suicide attempts in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Pediatrics. 2011;127(5):896–903. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Birkett M, Van Wagenen A, Meyer IH. Protective school climates and reduced risk for suicide ideation in sexual minority youths. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104(2):279–86. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Jun HJ, Corliss HL, Austin SB. Structural stigma and cigarette smoking in a prospective cohort study of sexual minority and heterosexual youth. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2014;47(1):48–56. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9548-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Jun HJ, Corliss HL, Bryn Austin S. Structural stigma and sexual orientation disparities in adolescent drug use. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;46:14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Pachankis JE, Wolff J. Religious climate and health risk behaviors in sexual minority youths: a population-based study. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(4):657–63. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck N, Flentje A, Cochran B. Offsetting risks: High school gay-straight alliances and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth. School Psychology Quarterly 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Herrick AL, Marshal MP, Smith HA, Sucato G, Stall RD. Sex while intoxicated: a meta-analysis comparing heterosexual and sexual minority youth. The Journal of Adolescent Health : Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2011;48(3):306–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Diaz EM. Who, what, where, when, and why: demographic and ecological factors contributing to hostile school climate for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38(7):976–88. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9412-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Palmer NA, Kull RM. Reflecting Resiliency: Openness About Sexual Orientation and/or Gender Identity and Its Relationship to Well-Being and Educational Outcomes for LGBT Students. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2015;55:167–178. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9642-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Dietz LJ, Friedman MS, Stall R, Smith HA, McGinley J, Brent DA. Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: a meta-analytic review. The Journal of Adolescent Health : Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2011;49(2):115–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy K, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly. 1988;15(4):351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer I. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(5):674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles M, Huberman A. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. 2nd. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Morse J, Field PA. Qualitative Research Methods for Health Professionals. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B. Ethical and regulatory issues with conducting sexuality research with LGBT adolescents: a call to action for a scientifically informed approach. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40(4):673–86. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9745-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. Changing Attitudes on Gay Marriage. (n.d.) Retrieved April 14, 2016, from http://www.pewforum.org/2015/07/29/graphics-slideshow-changing-attitudes-on-gay-marriage/

- PFLAG. Parents, Families, Friends and Allies United with LGBTQ People to Move Equality Forward. (n.d.) Retrieved April 14, 2016, from http://home.pflag.org/

- Poon C, Saewyc EM. “Out” yonder: Sexual minority youth in rural and small town areas of British Columbia. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:118–124. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.122945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porta C, Corliss H, Wolowic J, Johnson A, Fogel K, Gower A, Eisenberg M. Go-along interviewing with LGBTQ youth: Lessons learned from a community study in the U.S. and Canada. Journal of LGBT Youth. 2017;14(1):1–15. doi: 10.1080/19361653.2016.1256245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolfe G. Validity, trustworhiness and rigor: quality and the idea of qualitative research. Methodological Issues in Nursing Research. 2006;53(3):304–310. doi: 10.111/j.1365-2648.200603727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saewyc EM, Poon C, Homma Y, Skay CL. Stigma management? The links between enacted stigma and teen pregnancy trends among gay, lesbian and bisexual students in British Columbia. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 2008;17(3):123–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saewyc EM, Poon C, Wang N, Homma Y, Smith A, Society., T. M. C. Not Yet Equal: The Health of Lesbian, Gay, & Bisexual Youth in BC. Vancouver, BC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Saewyc EM, Skay CL, Sandra L, Reis EA, Bearinger L, Resnick M, Combs L. Hazards of Stigma: The Sexual and Physical Abuse of Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Adolescents in the United States and Canada. Child Welfare2. 2006;LXXXV(2):195–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis J, Owen N. In: Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 3rd. Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. San Francisco, CA: Josey-Bass; 2002. pp. 462–484. [Google Scholar]

- Toomey R, Ryan C, Diaz R, Russell S. High School Gay-Straight Alliances (GSAs) and Young Adult Well-Being: An Examination of GSA Presence, Participation, and Perceived Effectiveness. Applied Developmental Science. 2011;15(4):175–185. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2011.607378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- True Colors. True Colors’ Mentoring Programs. (n.d.) Retrieved April 14, 2016, from http://www.ourtruecolors.org/Mentoring/

- Wolowic JM, Heston L, Saewyc E, Porta C, Eisenberg M. Embracing the Rainbow: LGBTQ Youth Navigating “Safe” Spaces and Belonging in North America. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2016;58(2):S1. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.10.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]