Abstract

Social impact, defined as an effect on society, culture, quality of life, community services, or public policy beyond academia, is widely considered as a relevant requirement for scientific research, especially in the field of health care. Traditionally, in health research, the process of knowledge transfer is rather linear and one-sided and has not recognized and integrated the expertise of practitioners and those who use services. This can lead to discrimination or disqualification of knowledge and epistemic injustice. Epidemic injustice is a situation wherein certain kinds of knowers and knowledge are not taken seriously into account to define a situation. The purpose of our article is to explore how health researchers can achieve social impact for a wide audience, involving them in a non-linear process of joint learning on urgent problems recognized by the various stakeholders in public health. In participatory health research impact is not preordained by one group of stakeholders, but the result of a process of reflection and dialog with multiple stakeholders on what counts as valuable outcomes. This knowledge mobilization and winding pathway embarked upon during such research have the potential for impact along the way as opposed to the expectation that impact will occur merely at the end of a research project. We will discuss and illustrate the merits of taking a negotiated, discursive and flexible pathway in the area of community-based health promotion.

Keywords: Social impact, participatory, health research, knowledge, mobilization, health, promotion, knowledge, transfer, action research

Introduction

Internationally, there is an increasing need to account for the benefits of investing resources in health research by documenting its social impact. Following national reviews of how and whether research gets used for public benefit, accountability for social impact is now part of health research funding policy in some countries (Walshe and Davies 2013). Public institutions and charitable organizations increasingly require health research proposals to describe potential social relevance and impact. Further, there is growing recognition that research that is co-produced with practitioners, citizens, the public, and policy-makers is more likely to be of benefit in terms of fostering productive interaction and to have multiple impacts (Brett et al. 2014; Campbell and Vanderhoven 2016). Evaluation committees increasingly include representatives from advocacy and professional groups in order to review health research proposals for their relevance for practice. These drivers create opportunities to increase the impact of health research on society, but also raise questions about the type of impact that is valued, as well as how to organize the process of fostering impact (Penfield et al. 2013).

Several definitions of social impact circulate. The Higher Education Funding Council for England, for instance, defines social impact as ‘an effect on, change or benefit to the economy, society, culture, public policy or services, health, the environment or quality of life, beyond academia.’ (HEFCE 2015) The heterogeneity of interpretations of the term social impact is related to what is valued by whom. For example, higher education institutions traditionally defined impact via bibliometrics, because they value publication as the predominant strategy for knowledge generation. Governments are interested in arguments to establish priorities and to support decision-making processes for defining policies and for the organization of services, and the public defines it in terms of socioeconomic benefit and return on investment (Penfield et al. 2013). The heterogeneity of stakeholder perspectives on social impact raises the question whose perspective will prevail, and whether it is possible to collaborate with stakeholders in order to jointly decide on the social impact that is desirable in a particular context as well as to jointly decide how such impact can be monitored and evaluated.

Another issue is related to the route to achieving social impact. This is usually conceptualized as a process of knowledge transfer (Van De Ven and Johnson 2006). Academic researchers are conceived as the ones who start the process of knowledge production which is then passed on to and applied in practice. Critics point out that the production and application of knowledge is far more complex then this linear model suggests, and has argued that knowledge ‘mobilization’ is a better way to capture how knowledge is generated in complex networks. Realizing impact is in this vision not just an intellectual process and transfer, but also a socio-political activity of knowledge mobilization embedded in heterogeneous societal networks with many different stakeholders.

In line with the notion to jointly decide on the social impact to be achieved and the notion of knowledge mobilization, those practicing Participatory Health Research (PHR) and other forms of community and participatory approaches recognize that research co-produced with research users, stakeholders and patient groups is more likely to have a broad social impact (Greene 1988). Their aim is to engage with multiple stakeholders and interested partners in the whole research process, including framing ideas and research questions, so that outcomes are tailored to these interests and context (ICPHR 2013). One argument for working in this manner is that it is more likely to have impact (Donovan et al. 2014). First of all, the engagement of multiple stakeholders in the process, will enhance the relevance of the research, because those engaged will define themselves what kind of knowledge they need to improve their practice (Brett et al. 2014; Campbell and Vanderhoven 2016). Secondly, the engagement of multiple stakeholders will help to bring various perspectives on a problematic situation to the fore, which enhances the likelihood that the research will address the multifaceted nature and complexity of the practice at hand (Van De Ven and Johnson 2006). Thirdly, the engagement of multiple stakeholders in the process will help to create co-ownership of the knowledge generated, which enhances the chance that knowledge will be accepted and used by those stakeholders (Greene 1988).

Community and participatory approaches have not yet adequately described the wider social impact of their work (Cook et al. 2012). The purpose of our article is therefore to explore what sort of impact participatory research can achieve and how to realize social impact with a wide audience of stakeholders, involving them in a deliberative process of joint learning as the basis for creating social change. We will first of all recapture the critique on the knowledge transfer model, and then elaborate on some core characteristics of PHR and other forms of community and participatory research. The key theoretical spaces inhabited will be described as a route to recognizing how the way in which research is undertaken affects how and where impact might occur. Next, we will illustrate this approach via a set of case examples from the field of community-based health promotion based on an evaluation study that focused on impact and processes leading to impact. Finally, we will reflect on the merits of participatory approaches for social impact and favorable conditions as well as real-life complexities one may encounter in achieving social change.

Critique on knowledge transfer to foster social impact

The process of fostering impact in health research was, until recently, visualized as mainly a linear process where research funding (inputs) enabled design of research protocols and interventions (activities) leading to papers (outputs) and new or improved services (outcomes) producing better health and reduced mortality (longer term impact) (Greenhalgh and Fahy 2015). Described as ‘mode 1’ knowledge production, this approach to generating knowledge was firmly rooted in a particular scientific discipline and oriented toward adopting knowledge created by experts under controlled conditions. Knowledge was produced so that the recipients could accept and use it to change their understanding and their practices. This research production model places health researchers in the role of expert, providing health care practices and policy arenas and other recipients with information (Lavis et al. 2003). ‘Mode 2’ knowledge production emphasizes that knowledge needs to be generated in the context in which it will be used, incorporating different perspectives (transdisciplinarity) in a reflexive process (Nowotny, Scott, and Gibbons 2003). Although knowledge translation is defined as a dynamic and iterative process between researchers and knowledge users aiming to promote exchange and application, knowledge users continue to be defined in health disciplines as people who use research-generated knowledge (Canadian Institute of Health Research 2016).

Knowledge transfer is largely a passive and linear process (Weiss 1979), based on a ‘banking’ education process (Freire 1973), which does not by itself result in insights and motivation to use that knowledge on the side of the ‘recipients.’ People (so-called recipients or users) have practical and experiential knowledge and skills and the ability to learn and to make their own decisions, but in health systems, knowledge transfer often leads to a situation of disqualification or even destruction of their knowledge. This is especially problematic because researchers tend to approach the world in a scientific, often reductionist manner. Researchers specialize, focus, work from particular assumptions, models and theories and use specific instruments. These reductions are perfectly legitimate from an academic perspective, but leave out many other explanations and may not reflect the complexity of a societal problem (Van De Ven and Johnson 2006). There are also well-known challenges to applying research across different contexts. These include the relevance to different users, and the appropriateness and acceptability to different beneficiary groups. If not engaged, people often do not feel connected and intrinsically motivated to change their policy or practice on the basis of research findings produced elsewhere, and without them being involved (Greene 1988). Better implementation and communication of the research findings by means of various (social) media, lay publications and presentations will not solve the underlying problems related to knowledge transfer.

The second disadvantage of the research production model is that the focus tends to be on a limited number of stakeholders, specifically those who already have decision power: academics, physicians, board members of health care institutions, professionals at the political level. This can lead to research which lacks contextual validity and privileges a limited set of health outcomes over social impact. For example, a recent review of the value of peer support which involved diverse community stakeholders found that several of the key elements valued by peer support workers were entirely ignored when assessing impact (Harris et al. 2016). Leaving out minor voices and stakeholder perspectives leads to a situation of ‘epistemic injustice’ (Fricker 2001). Epistemic injustice arises when a person is not seen as credible as compared to providers, and this power differential is exacerbated when a patient doesn’t understand the language or comes from marginalized circumstances. This power inequity arises equally in health research when outsiders decide the research agenda and direct the process (Cornwall 2008). When people are not given the right to interpret and deal with their experiences, this has been named, ‘hermeneutic injustice’ (Fricker 2001). Recent writings from decolonizing and southern epistemologies proactively call for ‘cognitive justice’ and ‘knowledge democracy’ as essential for human rights globally (Barreto 2012).

To overcome epistemic injustice, linear knowledge transfer can be replaced by a dialogical model of co-learning (Freire 1982; Guba and Lincoln 1989; Wallerstein and Auerbach 2004; Abma 2005; Van De Ven and Johnson 2006; Abma, Leyerzaph, and Landeweer 2016). In collective actions, stakeholders engage in a process of asking and answering research questions together in order to create new understandings on issues that matter to them. Those who are researched are no longer seen as object, but become subjects and gain control over the research process (Freire 1973, 1982). Such collaboration supports the creation of meaningful dialog, and the variety of stakeholder perspectives in the dialog can broaden the scope and place possible understandings and solutions within a larger societal framework. In other words, such collaboration can lead to the development of a range of solutions, if stakeholders are willing to see many different types of knowledge and information as being valid. When this process is consistently supported throughout the development of programs, services and interventions a process of knowledge ‘mobilization’ is created and the conditions for change established.

In contrast to knowledge translation and knowledge transfer, knowledge ‘mobilization’ focuses on interactions to create knowledge and make sense of knowledge (Van De Ven and Johnson 2006). Knowledge mobilization is a ‘reciprocal and complementary flow and uptake’ of knowledge across diverse stakeholders (SS&HRC 2016) and may support bidirectional and multidirectional co-construction of knowledge. It is enabled by partnerships working across members of communities, academic communities, health care workers and those who are funding and supporting the resolution of issues that affect well-being. The process of knowledge mobilization values different types of knowledge alongside scientific research, focusing on what different types of people know, rather than assuming what one ought to know. To paraphrase Paulo Freire (1973), knowledge mobilization occurs when curious people, confronted with the world, engage in learning with and from each other in daily practice, apply their understandings to concrete situations, and transform knowledge into action on their reality.

In line with the notion of knowledge mobilization, Participatory Health Research (PHR) and other forms of community and participatory research recognize that research co-produced with research users, stakeholders, and patient groups is more likely to have a broad social impact, because it considers action, participation and community empowerment as central to the process of research. The intellectual history of PHR and related approaches and their core characteristics are presented below.

AR, PR, PAR, CBPR, and PHR: building on a rich intellectual history

Participatory health research (PHR) is a term used specifically for research into health or health care issues, usually, but not exclusively, found within community based practices where public health, social determinants, or clinical services and long-term care facilities are a key focus of the research. PHR builds on a rich socio-intellectual history, particularly action research, participatory research, participatory action research, as well as community-based participatory research.

What all these approaches have in common is that they draw on theories for practice that forefront the lived experience of those whose lives or work are central to the focus of the research. They have somewhat different geographical, social, historical, and intellectual starting points. Action research recognizes its roots broadly in the works of John Dewey and Kurt Lewin. Dewey criticized what he recognized as the traditional separation between knowledge and action in research practices. Lewin championed the value of the knowledge of those who were physically engaged with work being researched, and the value of questioning rather than accepting autocratic dictates about how work might be carried out. Inspired by earlier work on the relationships between autocracy and democracy in the workplace, Lewin’s work gave credence to:

the development of powers of reflective thought, discussion, decision and action by ordinary people participating in collective research on ‘private troubles’ that they have in common. (Adelman 1993, 8)

Action research (AR) is therefore constructed as a way of developing understandings through the practical experience of trying to improve a real situation, situated in local, experiential knowledge. Lewin concluded there can be ‘No action without research; no research without action.’ (Adelman, 8) Lewin’s particular concern was to develop action research as a means for improving conditions for minority groups, to help them seek ‘independence, equality, and co-operation’ and ‘to overcome the forces of exploitation’ and colonialization that had been prominent in their modern histories (Adelman 1993, 7–8). Thus, we have come to see action research as a form of inquiry, embedded in action, that uses the experience of trying to improve some practical aspect of a real situation as a means for developing our understanding of it.

The term, participatory research (PR) and participatory action research (PAR), came out of a more Southern tradition of academics in the 1970s throughout Latin America, Asia, and Africa, and scholars who espoused moving out of the academy into communities to confront structural injustices in society. Drawing from Marxism, liberation theology, the dialogical, and emancipatory writings of Paulo Freire (1970, 1973, 1982), they sought to engage in authentic dialog with communities to challenge the domination of knowledge by the elites (Fals-Borda and Rahman 1991). While there is a long list of multiple other terms that espouse collaborative knowledge creation, participatory action research often has been used as an integrative term globally (Wallerstein and Duran forthcoming). Like participatory research and participatory action research, PHR is an approach that emerged to deal with the limitations of research that, as a technique, privileged professional knowledge as expert knowledge. It is an approach that endeavors to honor democratic and participatory values and intends to foster dialog among as many stakeholders as possible, explicitly including the voices of those who commonly have less power to make themselves heard, for both methodological and moral imperatives.

PHR draws on both the AR as well as the PR and PAR tradition, and the many approaches that have developed in different countries and time periods under the umbrella of AR, PR, and PAR, all of which have their basis in broad social movements striving for a more democratic and inclusive society. This includes action research for educational purposes (e.g. Stenhouse 1975; Kemmis and McTaggart 1986), action research in organizational development (e.g. Lewin 1948), also Interactive-constructivist Research (e.g. Guba and Lincoln 1989; Abma 2005; Abma, Leyerzaph, and Landeweer 2016), and forms of Cooperative Inquiry (e.g. Heron 1996; Reason 1998).

Still another important tradition that needs to be mentioned here is Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR), which is widely used in Public Health in the US (e.g. Wallerstein et al. forthcoming). CBPR embodies both the forefronting of the link between theory and practice found within AR research, and the emphasis on engagement of those whose lives are at stake like in PR and PAR, but CBPR emphasizes that the starting point for participation lies within the community. PHR draws on this notion of the importance of the community, and the critique of structural inequalities and social injustice – which form the basis for health disparities and unmet population needs – as well as social transformation which requires deliberative-democratic, collective action (Abma and Baur 2012). It is the community which forms the base for socio-political action and structural changes. PHR and CBPR consider the participation and the empowerment of the community therefore as essential to the process and an end in itself. Community participation and empowerment are the hallmark of PHR (ICPHR 2013, 5). While CBPR finds its geographical and social base in the US and Canada and has been used internationally, such as in New Zealand, PHR is emerging as an umbrella international term.

In recent years, there has been a movement in some countries to increase the participation of people whose lives are affected by health issues by consulting them over the course of developing and implementing health research studies (e.g. National Health and Medical Research Council 2002; Cropper et al. 2010). People affected by the issue being studied are, for example, consulted in advance regarding research topics and priorities (e.g. Abma and Broerse 2010; Stewart et al. 2012). This has led to an increasing repertoire of more innovative data collection methods to engage study participants in a more active way in research. Reasons for the involvement of people with experience include: to improve the study question (make it more relevant); improve recruitment (a better sample); to improve the quality of the data by having a wider set of perspectives to draw on; to check that the analysis seems appropriate (face validity). More widely however, the focus for research remains likely to have been conceived by external players and may lack the commitment to addressing epistemic injustice and social inequalities of health provision found in research that takes a more radical view and includes moving beyond understanding of the individual and addressing societal and structural injustices.

All forms of community and participatory research, whether AR, PR, PAR, CBPR, or PHR have been concerned about co-optation and distinguish themselves from what can be seen as consultation or pseudo-participation. In participatory approaches, people decide together what their focus will be, how to formulate their research questions, what might be the most appropriate design and what forms of impact they want to realize. The primary underlying assumption is that ‘participation on the part of those whose lives or work is the subject of the study fundamentally affects all aspects of the research’ (ICPHR 2013, 5). This differs from the forms of research that co-opt participants into the use of more participatory methods, or even collaborate with participants to check a given protocol for research.

Mobilize knowledge for social impact and change

Fundamental to PHR and other community and participatory forms of research is the:

shared recognition that science is more than adherence to specific epistemological or methodological criteria, but is rather a means for generating knowledge to improve people’s lives. (ICPHR 2013, 5)

The aim is to enhance mutual understandings among stakeholders, to build new knowledge rather than to strive for simple consensus about current knowledge. With this, it intends to create a platform for dialog, learning together, and change, what Bridget Somekh (2002, 92) termed ‘the construction of knowledge with its enactment in practice.’ Thus, to foster learning processes, these researchers do not stand above practices but are embedded and engaged in practices, stimulating critical questioning and aiming for a joint understanding of the health situation and development of plans for action. This all starts from the belief in the creative power of human beings and their critical and reflexive capacity (Freire 1973, 1982).

It is essential to involve and integrate multiple perspectives to arrive at joint and shared understanding, the starting point being that each person and perspective can illuminate only part of reality. Nobody can ever get rid of her or his standpoint and frame of reference; knowledge is therefore always partial and embodied, meaning that knowledge is related to one’s feelings and emotions and situated-ness. The aim of involving multiple perspectives and different forms of knowledge (experiential, practical, traditional, and scientific) is to develop a richer and more meaningful portrayal of the investigated practice and to facilitate a learning platform for representing the multiple experiences, hopes and fears of those with direct experience as a route to reducing health inequalities. Such research is working from a horizontal, communicative approach of power, and critical of the traditional power asymmetries in which the researcher observations are viewed as objective and lived experience viewed as subjective, with the subjective considered less valuable. It considers these distancing approaches as barriers to learning, leaving power for action in the hands of external bodies that may well have a competing set of needs beyond the immediate needs of the communities where the research takes place.

To facilitate a space where people are able to contribute in an open manner, PHR and related research start with building relationally based partnerships, either formal or informal. Essentially, this requires an ‘open communicative space’ to discover jointly what moves and intrinsically motivates people to commit themselves to work together. The concept of communicative space has its roots in the work of Habermas (2003) who identified the ideal place for people to come together as a place of

… mutual recognition, reciprocal perspective taking, a shared willingness to consider one’s own conditions through the eyes of the stranger, and to learn from one another. (291)

This type of communication does not seek harmony as a means of engagement, but challenges the traditionally asymmetric relationship between those with lived experience (life or work experience) and external researchers, shifting toward an inclusive approach where the focus is on learning together to create new ways of acting. To do this, it is essential to cultivate an ethos of critical thinking, listening, and dialog (Freire 1973; Wallerstein and Auerbach 2004; Abma 2005; Abma, Leyerzaph, and Landeweer 2016). This process includes self-reflection about one’s identity and positionality of power, such as by race/ethnicity, education, role, research knowledge, etc. (Wallerstein and Duran 2006; Muhammad et al. 2014). This requires openness, receptivity, sensibility and critical reflection upon the assumptions, limitations and blind spots of oneself and one’s own discourse. In the process of collaborative learning and reflection, it may well be that the whole group will come back to the initial questions several times, seeing them again through a new lens formed by mutual critical reflexivity. This is part of the recursive, and often messy process of community and participatory research necessary to develop the shared learning that is the seed bed for action (Cook 1998). This ‘messy area’ is where participants have

deconstructed well-rehearsed notions of practice and aspects of old beliefs; are aware of the dawning of the new, but as yet have not made sense of it. It is where ‘mutually incompatible alternatives’ (Feyerabend 1975) are debated and wrestled with and become the means for moving beyond normative states of fitting happenings into previously experienced frameworks. (Cook 2009, 286)

The purpose of such activity is to move toward a vision of what could be constructed to harvest new meanings for practice from the debate. This prerequisite for co-laboring, working together across stakeholders serves to break down the more traditional notion of research where professional knowledge is separated from, and valued above, situational, visual and experiential knowledge, and the knowledge of tradition and coexistence. There are indeed many types of knowledge which need to be recognized and valued as legitimate as they provide necessary elements that underpin actions needed to guide the solving of major problems.

Pathways to social impact

PHR and other forms of community and participatory research accept that processes of change do not proceed in a planned and linear way and are influenced by a complex web of factors, including charisma, relational tensions, resistance, feelings of jealousy and other emotions, techniques and protocols, cultural value patterns, daily routines, and the political and economic context. These intersect in a complex and often non-linear and ‘messy’ way. These research approaches focuses on the actions and processes and considers these as more important to gain an understanding of a community or practice than previously formulated policy goals and plans made by external agents. Whilst impact is embedded in the processes of action research and PHR, recognizing, capturing and articulating that impact is a challenge given the interweaving of collaborations, processes and practices that are drawn together in complexity research (Thomson 2015). Most practices cannot be changed by a simple set of principles and rules or means-end thinking.

In community and participatory research, social impact is the outcome of intensive collaborations and partnerships between researchers and societal stakeholders, such as professionals and patient/client groups (those with lived experience). Impact means more than communicating research findings and delivering a ‘product’ or ‘service’ for society, it involves fostering social change within the wider complex social system in which the research is taking place. This includes a wide range of intermediate outcomes, such as new policies, sustainable interventions, more equitable power relations between communities, agencies, and academics; or strengthened agency capacities; as well as more distal health and health equity outcomes. It is expected that the processes of participation and the spaces for reflection and emotional engagement created in the course of dialogical research interactions enhance the potential for short-term, intermediate and long-lasting impacts, because of investment of those whose lives/work are integrally entwined with the focus of the research. Yet, many of the outcomes of research such as PHR, that is embedded in complex relationships, are not always possible to articulate at the beginning of a research cycle. As with action research, while some outcomes are desired or intended, others are not known with any degree of certainty. As Eileen Piggot-Irvine and her colleagues state, the research ‘does not always occur in a linear, lock-step fashion in a predictable way. And its endpoint is often open to new actions and learnings: a good AR project often has no well-defined ending.’ (Piggot-Irvine, Rowe, and Ferkins 2015, 549). Social impact is therefore not just an end ‘product’, but rather occurs throughout the research process and continues after it is completed. We now introduce an example of multiple case studies to show what kind of impact community and participatory research approaches can achieve, and illustrate what partnering practices are helpful to achieve social change and address structural health inequalities.

A set of case examples showing (pathways to) impact

In the United States, PHR is commonly referred to as community-based participatory research (CBPR), drawing from the Southern tradition of ‘participatory research’ and adding ‘community-based’ from the public health field. More recently, the term, community engaged research (CEnR), is being used, which includes a range of participation, from outreach through shared leadership. CBPR, similarly to PHR internationally, has situated itself on the higher end of the participatory spectrum, defined as collaborative efforts building on the strengths and priorities of the community to engage in research and actions to improve social and health equity. In the US, CBPR/CEnR have a specific history in seeking community partners often seen as belonging to geographic areas or sociocultural–political identities, such as neighborhoods, rural areas, or minority ethnic/racial groups or other social identity, such as LGBTQ, disability, or patients with a specific health condition in health care systems. With histories of organizing and activism, these communities often have been the basis for identifying stakeholder partners for collaborative research projects.

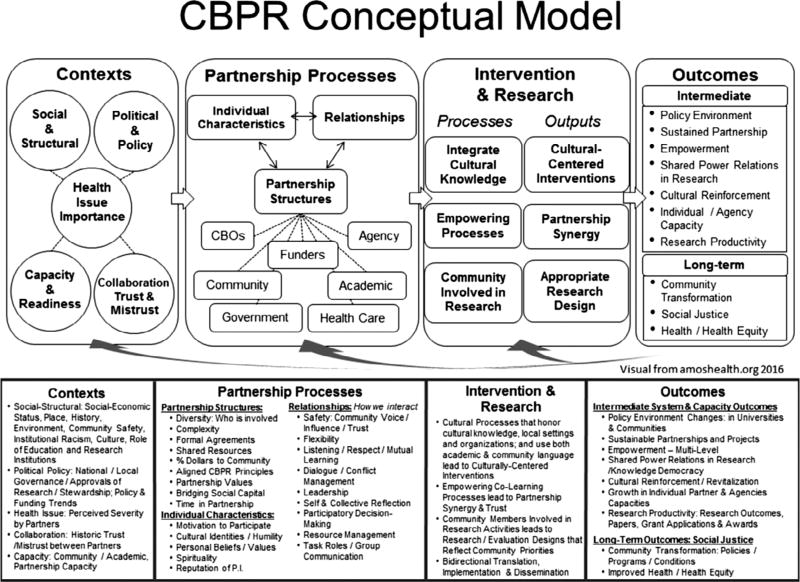

The set of case examples presented here illustrates the diversity of community and participatory research approaches across the US and their potential for broad impacts. These case studies were conducted as part of a fifteen-year research agenda to develop and test a CBPR conceptual model (see Figure 1) that illustrates pathways and the transformational potential of participatory practices towards social change impacts. The conceptual model was created from an intensive literature review, community partner consultations and guidance from a national advisory group. It starts from the social, historical, political and community contexts of the research; then identifies partnering practices, i.e. co-construction of knowledge, participatory decision-making; that impact intervention and research design and implementation, such as involving community members throughout all phases of research; and contribute to a wide range of research, capacity, and equity outcomes (Wallerstein et al. 2008). After model development, an NIH-funded ‘Research for Improved Health’ (RIH) study, as a partnership among the Universities of New Mexico and Washington, and a community partner, the National Congress of American Indians Policy Research Center, used a mixed-methods approach to identify facilitators and barriers to participatory research processes and impacts (Lucero et al. 2016). Internet surveys were conducted on 200 federally funded academic-community research partnerships; and seven in-depth qualitative case studies were purposefully selected on diversity (See Table 1 for an overview).

Figure 1.

Paysways to impact.

Table 1.

Overview of the case studies.

| Projects: Health and social issues | Region | Population | Partners |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healing of the Canoe: Substance abuse prevention/Youth life skills | Pacific Northwest | Native youth | University of Washington and two tribes |

| Men on the Move: Cardiovascular disease prevention/Men’s employment | Boothill, Missouri | African-American men | St. Louis University; community members |

| Bronx HealthREACH : Faith-based diabetes management and prevention/Unequal Access to care | Bronx, New York | African-American and Latino congregations | Institute for Family Health; New York University; Churches and community organizations |

| Lay Health Workers to Increase colo-rectal cancer screening and nutrition education | San Francisco | Residents of Chinatown 55–64 | University of California, S.F.; S.F. State; NICOS (community partner), Chinatown health dept. |

| Tribal Nation: Barriers to Cancer Prevention | South Dakota | Native Adults | Black Hills Center for American Indian Health and tribe |

| South Valley Partners for Environmental Justice: Policies to reduce unequal exposure to toxins | Albuquerque, New Mexico | Hispanic/Latino population | University of New Mexico, Bernalillo County, community partners |

| Assessment of health issues for deaf and hearing impaired | Rochester, New York | Deaf or Hearing impaired | Center for Deaf Health, University of Rochester; partners from Deaf Community |

Through the internet survey, multiple context, partnering practices, and outcomes were measured and assessed (Oetzel et al. 2015). Social impact or outcomes ranged from: synergy, a short-term outcome; to intermediate outcomes, i.e. sustainability, changed power relations, and culturally centered interventions; to more distal outcomes and impacts, such as community transformation of programs, services, and policies, and improved health and health equity. While evidence from the internet surveys has identified partnering practices associated with outcomes, this article reports on examples of processes, multi-level outcomes and social impacts that were identified within the qualitative case studies.

These case studies created the opportunity to assess mechanisms of the pathways, how the achievement of short-term and intermediate outcomes can lead to greater health and social impact. Achievement of short-term synergy, for example, or the capacity of partners to work collaboratively to get the tasks done, can create as an intermediate outcome, greater equality between academic and community knowledge, and therefore facilitate the implementation of programs and services that ‘fit’ within the cultural community context. If the culture and context are more appropriate, then the likelihood of the outcome of program sustainability grows and health can be improved over the long run. Specific examples are provided below.

Case study methods included document review, on-site visits, 10–15 academic and community partner interviews, 1–2 partnership focus groups, historical timelines, and a brief survey (instruments at [http://cpr.unm.edu/research-projects/cbpr-project/RIH.html]). Questions asked about the different domains of the CBPR model, including community and historical contexts; trajectories of partnerships; partnering practices that worked best, such as dialog, leadership, trust-building, and power-sharing; challenges faced over time; and, importantly for this paper, the impacts they perceived, as generated from their partnering practices on knowledge co-creation, on their research, and on communities. Using ATLAS. ti, transcripts were coded deductively from model constructs, and inductively from the data. Thematic narratives were constructed with quotes, sent to case studies for fact-checking and co-interpretation, and when finalized, returned to partnerships.

These case studies well documented co-construction of knowledge and a transformational social justice approach, as also recognized in the PHR literature. In terms of contextual factors, many interviewees across all case studies talked about a longer history of community advocacy and their mutual collaborations before the research grant. They argued that their historical contexts needed to be considered for confronting the complexities of injustices, rather than conceiving change as instrumental or technical. These included such histories as the 1970s ‘burning of the Bronx’ where landlords of poor Latino and African-American families ignored housing conditions and collected money from arsonist-set fires; the memory of a tribal village destroyed by the army one hundred years ago; industry disregard for historic Latino ‘land grant’ ownership with the development of polluting industries in their neighborhoods; Chinese immigrant concerns about being persecuted over immigrant status; or the historic stigma which the Deaf community perceived in how outsiders viewed their use of American Sign Language.

Interviewees talked about the importance of understanding local historical and socio-cultural or political contexts and building partnership practices based on identifying community strengths in their leadership or knowledge base; and on cultivating listening practices that honored community voices.

Here we’ve got local knowledge in the community. They have a good sense of what works best, what has worked best in past years. Sometimes you see [community members] not wanting to speak loud so they are heard, when it’s so important that they speak loud. So that the university partner, you could say, hears them.

Our CRC [Community Resource Committee] group has pastors, physicians, leaders in the public health arena, very important people with a lot of experience who come from different spheres; and in their own world they are their leaders. The people are used to listening to them. And there’s that level of respect that I think came from working together for many years.

They talked about collaborative research processes, and especially the role of engaging community members in all the steps of the research and adopting principles of mutual respect.

So our deaf committee members are … they’re doing the data collection … They run recruitment … They’re involved with analysis…They’re involved in all steps along the way.

CBPR really opens up the communication channels … not everyone is a trained researcher, but we all have the same goal … and that really influences how we work together. We all have different expertise … For different issues, we go to different people. And most of the time we respect the other party’s expertise, and we accept what they suggest.

In the Bronx HealthREACH case study, specifically, it meant recognizing the historic role church leaders had in the civil rights movement, and their current role of integrating faith with human dignity as the basis for actions for improved health and social impacts among disenfranchised African American and Latino communities in New York city. As one interviewee elegantly stated, ‘You’re not one little voice crying in the wilderness. You have voices. It’s a lot of good stuff [that] has come out of this project.’ With the enhanced synergy of the partnership through a nutrition and diabetes intervention research project, pastors were able to create intermediate outcomes, such as transforming church dinners to be more nutritious, encouraging healthy behaviors through faith-based teachings, and engaging local stores next to churches to sell fruits and vegetables (Kaplan et al. 2009). As an unintended outcome of the research funding, their success at greater community participation led to the partnership successfully forcing New York City schools to adopt low-fat milk as a new policy (Golub et al. 2010), and challenging lack of access to quality medical care for residents in zip (post) codes that were predominantly poor and low-income. These intermediate outcomes are beginning to show new more long-term social impacts of community empowerment among community members in the participating churches in the Bronx to promote their own health, including greater equity related to access to healthy foods and healthcare. By understanding the importance of challenging inequitable conditions, the Bronx HealthREACH project as well as several other case studies based their participatory practices in social justice values and strategies that broadened their impacts to improved social conditions (Devia et al. 2017; Barnett et al. forthcoming; Oetzel et al. forthcoming).

None of these changes in each of the case studies took place in one research grant cycle, but were part of longer-term relationships that spanned distinct periods of having or not having funding. Relationship-building, evidence of listening to each other, and commitment was shared which allowed trust and the ability to tackle large goals to be maintained over time. A key lesson is that social impact can be fostered by investing in relational and dialogical processes with diverse community and academic stakeholders, creating mutual trust, and keeping faith in the process, even with the knowledge that change, both intended and unintended, means commitment over the long haul.

Discussion

The social impact of health research is important if the final goal of health research is to contribute to an improvement in the quality of health and health care, particularly for those whose voices are seldom heard. While we know that this cannot be achieved by giving advice or proposing recommendations, alternatives to reach social impact have not widely been discussed in the literature. As many researchers suggest, achieving social impact involves complex and dynamic collaborative processes with community members, patients/service users, health and social service professionals, policy-makers, and other stakeholders whose interests and values need to be taken into account to achieve social impact. The expectation of PHR and other forms of community and participatory research is that it makes health research more directly related to communities and health care practices, taking up issues and concerns which are experienced as relevant and pressing by stakeholders. Secondly, it has been argued that PHR and related approaches fosters social impact in terms of actual changes in communities and practices, as participants are motivated and supported in redesigning their live and work in a responsible way. In the third place, it has been argued that PHR and alike approaches foster the reflection on and dialog about the expected impact and experienced outcomes of the research process, providing new ways to collaboratively address the issue of social impact. Yet, the expectation that PHR has several advantages when it comes to social impact has seldom been documented (Cook et al. 2012).

In this article, we have tried to show what type of social impact PHR and other forms of community and participatory research can create and pathways of how this can be realized. This involves learning processes and knowledge ‘mobilization’ integrating various sources of knowledge and building on relevant issues discussed and formulated by multiple stakeholders. PHR may contribute to this by motivating stakeholders in practice to reflect on their lives and work and, through dialog, to come to a better understanding of what is at stake in their communities and thus to jointly work for social impact and change. PHR acknowledges that changes in communities require collaboration with and among participants, and is aware of the interpretative nature of the notion of social impact. What counts as impact is dependent on the views and experiences of those involved. Rather than taking for granted stakeholders’ views, PHR researchers stimulate participants to critically investigate their own assumptions and come to a joint understanding of what is a meaningful change in their context.

The presented set of qualitative case studies from an evaluation study of CBPR projects in the US – which reflect a PHR approach emphasizing action, participation and community empowerment – have revealed that this impact varies from context to context. Outcomes ranged from: synergy, a short-term outcome; to intermediate outcomes, i.e. sustainability, changed power relations between academics and communities, enhanced agency capacities, and culturally centered interventions; to more distal outcomes, such as community transformation of programs, services, and policies, and health equity outcomes. What counted as impact could not be fully stated at the beginning of a project, and emerged over time. The processes and pathways that led to social impact were influenced by many historical, leadership, and other socio-political contextual factors, and were not linear, but stretched over a long time period. Across all case studies trustful relationships and mutual collaborations embedded in and recognizing the local history of communities appeared to be crucial to reach impact. Another important factor was related to the inclusive research strategy where communities were engaged in the research, and felt there was a communicative space to share various sorts of understandings.

For a participatory research approach and its social impact to get noticed and recognized, it is critical to understand how social impact gets conceived. We see in other fields that this is too often limited to what is measurable and observable. Considering the evidence from the case studies this is a weak way to understand and articulate the impact in terms of social transformation. Changes in practices as a result of changes in thinking and culture are important, but not easily recognized and can be difficult to articulate. Moreover, these changes often happen over a long period of time, as the case studies showed. The move from single cases to encompassing multiple, mutually interacting factors in health promotion reflects participatory research’s embrace of contextual interaction, mutually shaping forces, and webs of influence in human life and health. Social impact cannot, therefore, be determined by researchers alone, it is the joint and collaborative effort of many with the fundamental work being done by people with lived experience. The role of the participatory researcher is crucial, however, in supporting reflection and dialog to enable critical awareness of hierarchies and of power relations that otherwise are taken for granted.

Conclusion

Social impact is becoming increasingly important in health (care) research. PHR and other community or participatory research approaches provide a means to involve stakeholders in the research process, enlarging the relevance for and the impact on society. By engendering reflection and dialog researchers and participants can better work together and find or create ways to deal with issues and improve health and health care. In this process, what counts as social impact itself is not given. In the end, what counts as a better community or practice is to be determined in dialog amongst multiple stakeholders, and is generated through working together and learning together. This insight is relevant for social impact of PHR and health (care) research more in general.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abma TA. Responsive Evaluation: Its Meaning and Special Contribution to Health Promotion. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2005;28(3):279–289. [Google Scholar]

- Abma TA, Baur V. Seeking Connections, Creating Movement. The Power of Altruistic Action. HCA: Journal of Health Philosophy and Policy. 2012;22(4):366–384. doi: 10.1007/s/10728-012-0222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abma TA, Broerse J. Patient Participation as Dialogue: Setting Research Agendas. Health Expectations. 2010;13(2):160–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2009.00549.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abma TA, Leyerzaph H, Landeweer E. Responsive Evaluation in the Interference Zone between System and Lifeworld. American Journal for Evaluation. 2016:1–14. doi: 10.1177/1098214016667211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adelman C. Kurt Lewin and the Origins of Action Research. Educational Action Research. 1993;1(1):7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett S, Cuculick J, DeWindt L, Matthews K, Sutter E. National Center for Deaf Health Research: CBPR with deaf communities. In: Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel J, Minkler M, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity. 3. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto J-M. Epistemologies of the South and Human Rights: Santos and the Quest for Global and Cognitive Justice. Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies. 2012;21(2):395–422. [Google Scholar]

- Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, Herron-Marx S, Hughes J, Tysall C, Suleman R. Mapping the Impact of Patient and Public Involvement on Health and Social Care Research: A Systematic Review. HEX. 2014;17(5):637–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2012.00795.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell H, Vanderhoven D. Realising the Potential of Co-production. Manchester, NH: N8 Research Partnership; 2016. [Accessed March 22]. Knowledge That Matters. http://www.n8research.org.uk/view/5163/Final-Report-Co-Production-2016-01-20.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institute of Health Research. [Accessed September 21];2016 http://www.cihr-irsc-gc.ca/e/29418.html#2.

- Cook T. The Importance of Mess in Action Research. Educational Action Research. 1998;6(1):93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Cook T. The Purpose of Mess in Action Research: Building Rigour Though a Messy Turn. Educational Action Research. 2009;17(2):277–291. [Google Scholar]

- Cook T, Boote J, Buckley N, Turnock C, Vougioukalou S. Embedding Research Impact: Assessing Participatory Research Impact and Legacy. 2012 Case Study and Final Report. JISC/NCCPE. http://repository.jisc.ac.uk/5116.

- Cornwall A. Unpacking ‘Participation’ Models, Meaning and Practices. Community Development Journal. 2008;43(3):269–283. [Google Scholar]

- Cropper S, Porter A, Williams G, Carlisle S, Moore R, O’Neill M, Roberts C, Snooks H. Community Health and Wellbeing. Action Research on Inequalities. Bristol: Policy Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Devia C, Baker E, Sanchez Youngman S, Barnidge E, Golub M, Motton F, Muhammad M, Ruddock C, Vicuña B, Wallerstein N. Advancing System and Policy Changes for Social and Racial Justice: Comparing a Rural and Urban Community-based Participatory Research Partnership in the U.S. [10.1186/s12939-016-0509-3];International Journal for Equity in Health. 2017 16:182. doi: 10.1186/s12939-016-0509-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan C, Butler L, Butt AJ, Jones TH, Hanney SR. Evaluation of the Impact of National Breast Cancer Foundation-funded Research. The Medical Journal of Australia. 2014;200(4):214–218. doi: 10.5694/mja13.10798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Borda O, Rahman M, editors. Action and Knowledge. Breaking the Monopoly with Participatory Action Research. New York: Apex; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Feyerabend P. Against Method: Outline of an Anarchistic Theory of Knowledge. London: Verso; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Herder & Herder; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Extension or Communication. In: Bigwood Louise, Marshal Margaret., editors. Education for Critical Consciousness. New York: The Seabury Press; 1973. http://www.seedbed.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Freire-Extension-or-Communication.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Creating Alternative Research Methods: Learning to Do It by Doing It. In: Hall B, Gillette A, Tandon R, editors. Creating Knowledge: A Monopoly? Participatory Research in Development. Vol. 1. New Delhi: Society for Participatory Research in Asia; 1982. pp. 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Fricker M, editor. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Golub M, Charlop M, Groisman-Perelstein AE, Ruddock C, Calman N. Got Low-fat Milk? How a Community-based Coalition Changed School Milk Policy in New York City. Fam Community Health. 2010;34:S44–53. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e318202a7dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene JC. Stakeholder Participation and Utilization in Program Evaluation. Evaluation Review. 1988;12(2):91–116. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T, Fahy N. Research Impact in the Community-based Health Sciences: An Analysis of 162 Case Studies from the 2014 UK Research Excellence Framework. BMC Medicine. 2015;13(1) doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0467-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Fourth Generation Evaluation. Beverly Hills (CA): Sage; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas J. Truth and Justification. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Harris J, Croot L, Thompson J, Springett J. How Stakeholder Participation Can Contribute to Systematic Reviews of Complex Interventions. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2016;70(2):207–214. doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-205701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron J. Co-Operative Inquiry: Research in the Human Condition. London: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- HEFCE (Higher Education Funding Council for England) [Accessed March 22, 2016];REF Impact. 2015 http://www.hefce.ac.uk/rsrch/REFimpact/

- ICPHR (International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research) Position Paper 1: What is Participatory Health Research? Version: Mai 2013. Berlin: International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan SA, Ruddock C, Golub M, Davis J, Foley R, Sr, Devia C, Rosen R, et al. Stirring up the Mud: Using a Community-based Participatory Approach to Address Health Disparities through a Faith-Based Initiative. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2009;20(4):1111–1123. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemmis S, McTaggart R. The Action Research Planner. Geelong: Deakin University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Lavis J, Robertson J, Woodside C, McLeod C, Abelson J. How Can Research Organizations More Effectively Transfer Research Knowledge to Decision Makers? Milbank Quarterly. 2003;81:221–248. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.t01-1-00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin K. Resolving Social Conflicts. New York: Harper; 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Lucero J, Wallerstein N, Duran B, Alegria M, Greene-Moton E, Israel B, Kastelic S, et al. Development of a Mixed Methods Investigation of Process and Outcomes of Community Based Participatory Research. Journal of Mixed Methods. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1558689816633309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad M, Wallerstein N, Sussman A, Avila M, Belone L. Reflections on Researcher Identity and Power: The Impact of Positionality on Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) Processes and Outcomes. Critical Sociology. 2014 doi: 10.1177/0896920513516025. Published first online 30 May 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Summary Statement on Consumer and Community Participation in Health and Medical Research National Health & Medical Research Council Consumers. Canberra: Health Forum of Australia; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nowotny H, Scott P, Gibbons M. Introduction: Mode 2’Revisited: The New Production of Knowledge. Minerva. 2003;41(3):179–194. [Google Scholar]

- Oetzel J, Duran B, Sussman A, Pearson C, Magarati M, Khodyakov D, Wallerstein N. Evaluation of CBPR Partnerships and Outcomes: Lessons and Tools from the Research for Improved Health Study. In: Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel J, Minkler M, editors. Community-based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity. 3. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Oetzel J, Zhou C, Duran B, Pearson C, Magarati M, Wallerstein N. Establishing the Psychometric Properties of Constructs in a Community-based Participatory Research Conceptual Model. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2015;29(5):e188–e202. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.130731-QUAN-398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penfield T, Baker MJ, Scoble R, Wykes MC. Assessment, Evaluations, and Definitions of Research Impact: A Review. Research Evaluation. 2013;rvt021:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Piggot-Irvine E, Rowe W, Ferkins L. Conceptualizing Indicator Domains for Evaluating Action Research. Educational Action Research. 2015;23(4):545–566. [Google Scholar]

- Reason P, editor. Human Inquiry in Action. London: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- SS&HRC (Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council) [Accessed 24 March 2016];2016 http://www.sshrc-crsh.gc.ca/funding-financement/programs-programmes/definitions-eng.aspx#km-mc.

- Somekh B. Inhabiting Each Other’s Castles: Towards Knowledge and Mutual Growth through Collaboration. In: Day C, Elliott J, Somekh B, Winter R, editors. Theory and Practice in Action Research: Some International Perspectives. Oxford: Symposium Books; 2002. pp. 79–104. [Google Scholar]

- Stenhouse L. An Introduction to Curriculum Research and Development. London: Heinemann; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart RJ, Caird J, Oliver K, Oliver S. Patients’ and Clinicians’ Research Priorities. Health Expectations. 2012;14(4):439–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00648.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson P. Action Research with/against Impact. Educational Action Research. 2015;23(3):309–311. [Google Scholar]

- Van De Ven AH, Johnson PE. Knowledge for Theory and Practice. Academy of Management Review. 2006;31(4):802–821. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Auerbach E. Problem-posing at Work: Popular Educators Guide. Edmonton: Grass Roots Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Duran B. Using Community Based Participatory Research to Address Health Disparities. Health Promotion Practice. 2006;7(3):312–323. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Duran B. The Theoretical, Historical and Practical Roots of CBPR. In: Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel J, Minkler M, editors. Community Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity. 3. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel J, Minkler M. Community-based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity. 3. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Oetzel J, Duran B, Tafoya G, Belone L, Rae R. What Predicts Outcomes in CBPR?” In 2008. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community Based Participatory Research for Health: Process to Outcomes. 2. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass; 2008. pp. 371–392. [Google Scholar]

- Walshe K, Davies HT. Health Research, Development and Innovation in England from 1988 to 2013: From Research Production to Knowledge Mobilization. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy. 2013;18:1–12. doi: 10.1177/1355819613502011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss CH. The Many Meanings of Research Utilization. Public Administration Review. 1979;39:426–431. [Google Scholar]