Abstract

Azobenzene photoresponsive elements can be installed on sulfonylureas, yielding optical control over pancreatic beta cell function and insulin release. An obstacle to such photopharmacological approaches remains the use of ultraviolet-blue illumination. Herein, we synthesize and test a novel yellow light-activated sulfonylurea based on a heterocyclic azobenzene bearing a push-pull system.

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is a modern pandemic currently affecting ~ 10% of the global population. This disease is characterized by diminished insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells, which together with peripheral resistance to the secreted hormone, leads to defective glucose homeostasis.1 The resulting elevated glucose concentration drives a variety of complications including heart disease, cancer, retinal degeneration, and nerve and vascular problems.2

While current medical treatments work well, they are associated with complications largely due to off-target or persistent actions.3 Moreover, they are unable to recreate pulsatile insulin release, a more effective signal for glucoregulation.4 Thus, T2D is ideally suited to photopharmacology, which harnesses the temporal precision of light to spatiotemporally deliver drug activity.5 We have recently shown that a sulfonylurea possessing an azobenzene photoresponsive element (a.k.a. AzoSulfonylurea) can be used to optically control beta cell function and insulin release via its effects on ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels and Exchange Protein directly Activated by cAMP 2A (Epac2A) signalling.6

However, a significant barrier to the use of such ‘azo-drugs’ for T2D treatment is their ultraviolet-blue absorption spectra, increasing phototoxicity and limiting tissue penetration due to photon scattering.7 By contrast, visible/near infrared wavelengths demonstrate better penetrance in the body. 8

Spurred on by recent studies of ortho- or para-substituted azobenzenes,9–11 we therefore devised a novel approach for the synthesis of wavelength-tuned photopharmaceuticals with red-shifted photochromism. An AzoSulfonylurea based on glimepiride was achieved by installing a heterocyclic aromatic unit, rather than sterically bulky electron-donating halogen or amine moieties (Scheme 1).

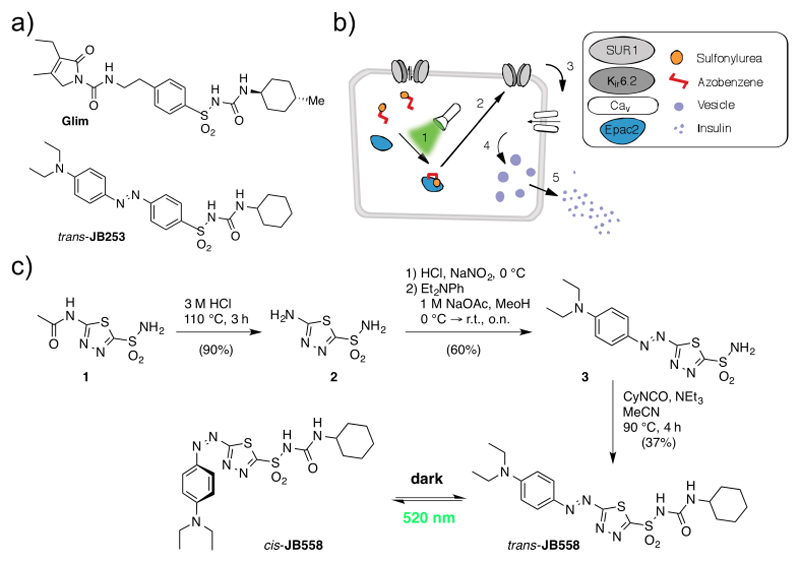

Scheme 1.

(a) Structures of glimepiride (Glim) and the original blue light-responsive AzoSulfonylurea JB253 for comparison. (b) The logic of a red-shifted AzoSulfonylurea. Following illumination with green-yellow light (1), the AzoSulfonylurea binds Epac2A, closing KATP channels (2) and opening voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (Cav) (3). This allows optical control of Ca2+ influx (4) and insulin secretion (5). (c) Synthesis of the AzoSulfonylurea JB558 that can be switched from the trans- to the cis-isomer using green/yellow light.

Starting with the deacetylation of acetazolamide (1) in refluxing HCl, heterocycle 2 was obtained that could be further diazotized with in situ generated HNO2. Trapping the resulting diazonium salt with N, N-diethylaniline generated sulfonamide azobenzene 3. Finally, reaction with cyclohexyl isocyanate yielded JB558 via acylation of the sulfonamide, giving unprecedented access to a sulfonylurea containing a heterocyclic azobenzene. While yields were reduced compared to the previously described JB253 (37% versus 97%),6 this was most likely due to the presence of a less reactive sulfonamide intermediate, as predicted by the lower pKa value for 3 (7.36, Fig. S1) and JB558 (2.35, see SI).

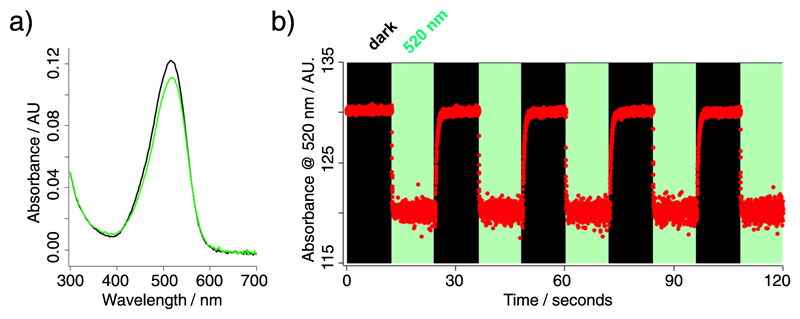

JB558 possessed a red-shifted absorption spectra (λmax = 526 nm) in DMSO (Fig. 1a), and could be repeatedly photoconverted to its cis-state with green-yellow light (λ = 520 nm) (Fig. 1b). Thermal back relaxation occurred rapidly in the dark and switching kinetics were within the millisecond range (τcis = 64.9 ± 1.5 ms; τtrans = 410.8 ± 12.6 ms), without obvious decomposition (Fig. 1b). JB558 was stable in the presence of Escherichia coli azoreductase, an enzyme expected to limit oral bioavailability through diazene cleavage in the intestine (Fig. S2).

Figure 1.

(a) UV-Vis spectra of JB558 in DMSO following illumination with λ = 520 nm (green) or under dark-adapted conditions (black). (b) Robust photoswitching between cis- and trans-JB558 induced with λ = 520 nm and dark, respectively.

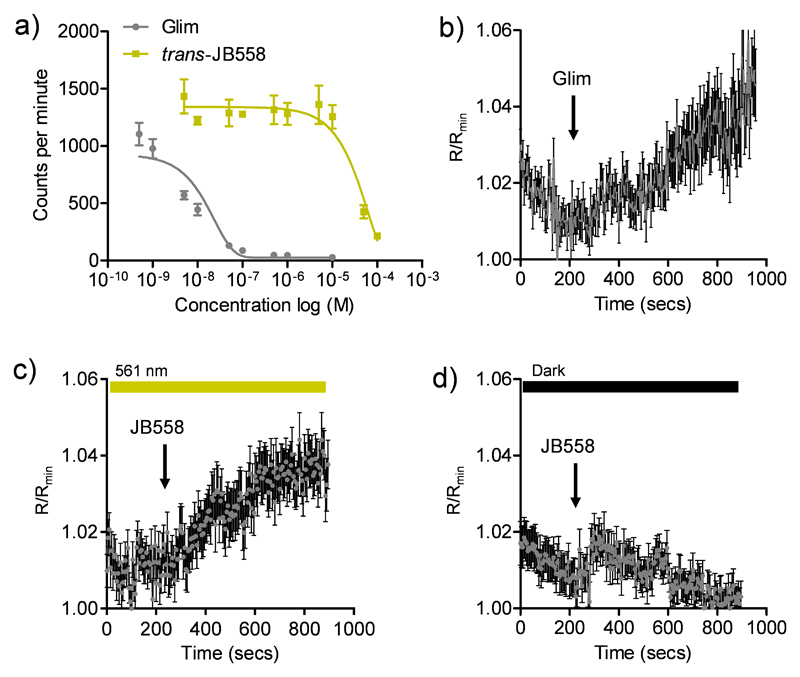

To determine the binding affinity of JB558 to the KATP channel subunit SUR1, as well as Epac2A, [3H]-glibenclamide displacement and FRET assays were performed. While trans-JB558 bound SUR1 with ~10,000-fold less affinity than glimepiride (IC50 (trans-JB558) = 37.3 µM; IC50 (Glim) = 1.8 nM) (Fig. 2a), it was able to strongly and light-dependently activate an Epac2A-camps biosensor containing the sulfonylurea binding domain12 (Fig. 2b-d).

Figure 2.

(a) trans-JB558 and glimepiride (Glim) displace [3H]-glibenclamide from SUR1 (n = 3 repeats). (b) Glimepiride decreases FRET (shown here as an increase in R/Rmin) in HEK293T cells expressing full length Epac2-camps (n = 32 cells). (c) As for (b) but cis-JB558 (λ = 561 nm) (n = 41 cells). (d) As for (c) but trans-JB558 (dark) (n = 37 cells). Values represent mean ± s.e.m.

Electrophysiological recordings of K+ currents in HEK293T-SUR1-Kir6.2 cells revealed partial KATP channel blockade by trans-JB558, presumably due to the momentary stationary state favouring some continued cis-isomerisation (Fig. S3).

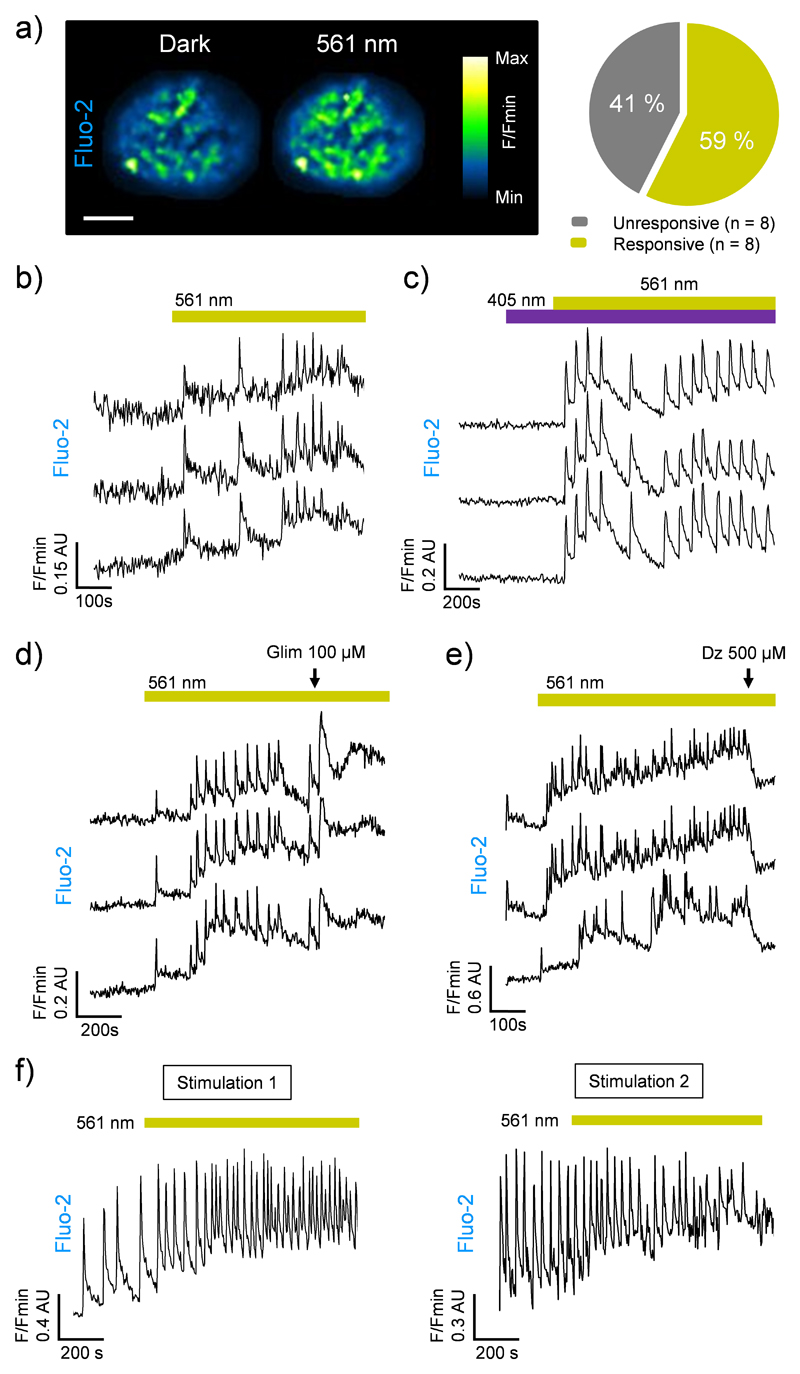

We next assessed the photoswitching properties of JB558 in native beta cells where sulfonylurea-mediated KATP channel-Epac2A signalling is intimately linked to voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel (VDCC) activity and insulin exocytosis.13–16 As expected, JB558 was able to evoke large increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations in ~60% of beta cells following exposure to yellow (λ = 561 ± 5 nm)- (Fig. 3a and b), but not violet (λ = 405 ± 5 nm)-light (Fig. 3c). These effects were potentiated using a high concentration of glimepiride (Fig. 3d), and abrogated using diazoxide (Fig. 3e) to force open the KATP channel pore. Repeated switching of cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations could be achieved in the same islet following a brief period of dark exposure to induce trans-JB558 accumulation (Fig. 3f).

Figure 3.

(a) JB558 increases intracellular Ca2+ concentrations in 59% of beta cells residing within rodent islets of Langerhans following illumination with λ = 561 nm (scale bar = 75 µm) (n = 8 islets). (b) Photoswitching is rapid following exposure to λ = 561 nm. (c) As for (b), but showing the absence of photoswitching with λ = 405 nm. (d) A high concentration (100 µM) of glimepiride (Glim) augments JB558-stimulated Ca2+ rises. (e) Diazoxide (Dz) reverses cis-JB558-induced Ca2+ fluxes. (f) Reversible manipulation of Ca2+ transients can be achieved in the same islet following thermal back relaxation of JB558 in the dark (5 min between stimulation 1 and 2). Traces represent n = 6-10 recordings from 3 animals. Islets were maintained in 5 mM D-glucose throughout.

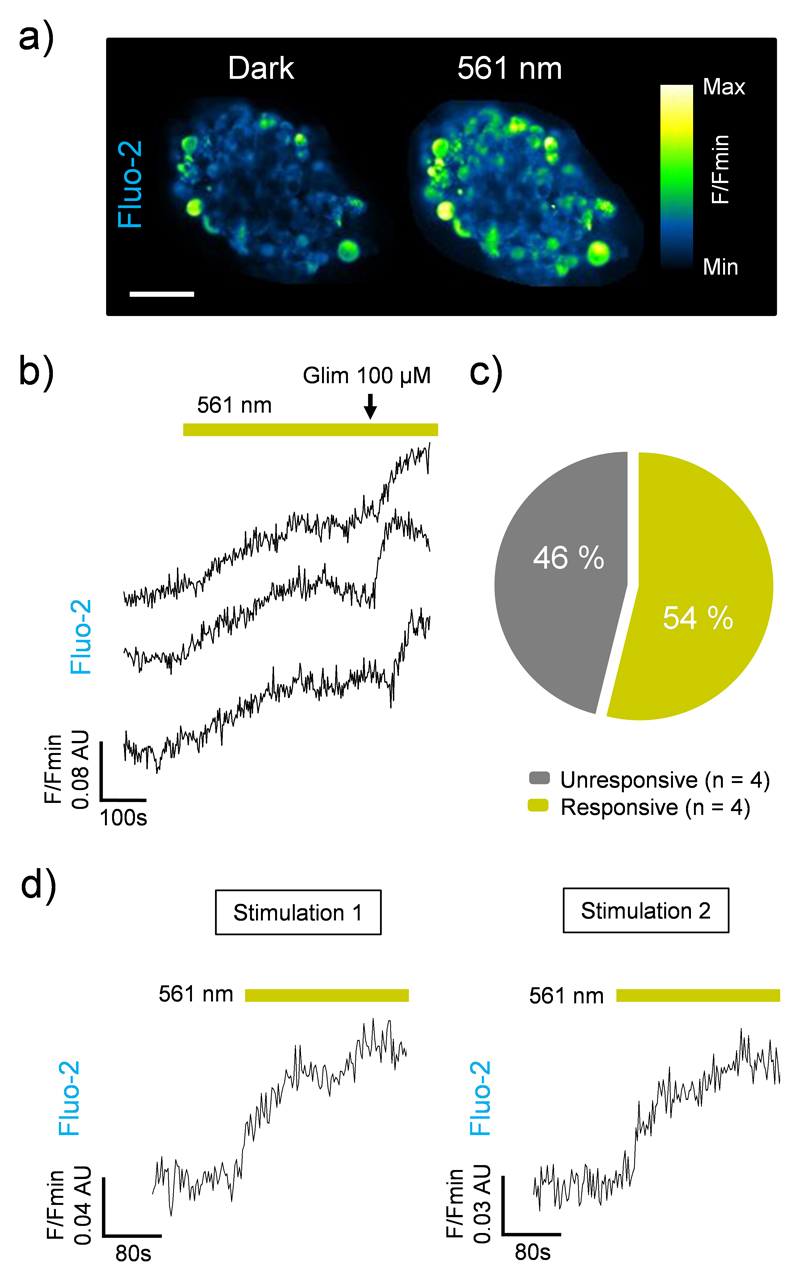

Similar to the results observed in rodent tissue, cis-JB588 was able to confer light-sensitivity on Ca2+-spiking activity in human pancreatic islets (Fig. 4a-c), and this effect could be reversed following 5 min relaxation in the dark (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4.

(a) JB558 increases intracellular Ca2+ concentrations in human beta cells in response to illumination with 561 nm to induce cis-formation (scale bar = 50 µm). (b) Photoswitching is rapid following exposure to 561 nm and can be potentiated with glimepiride (Glim). (c) cis-JB588 activates 54% of beta cells (n = 4 islets). (d) Reversible manipulation of Ca2+ rises following thermal back relaxation of JB558 in the dark (5 min between stimulation 1 and 2). Traces represent n = 3-9 recordings from a single donor. Islets were maintained in 5 mM D-glucose throughout.

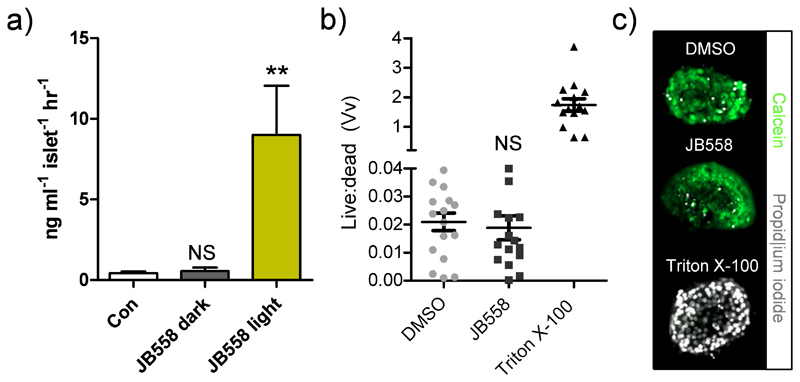

To link photocontrol of Ca2+ levels with insulin secretion, batches of rodent islets were incubated with JB558 and exposed to either dark (no illumination) or light (λ = 560 ± 10 nm). JB558–treated islets kept under dark conditions were no different to controls (5 mM glucose-alone) (Fig. 5a), suggesting that the observed stationary state KATP channel block was insufficient to elicit exocytosis. By contrast, irradiation dramatically stimulated insulin release (Fig. 5a). Finally, cytotoxicity assays demonstrated that JB558 did not adversely affect cell viability, as assessed using the vital stain calcein and the necrosis indicator propidium iodide (Fig. 5b and c).

Figure 5.

(a) JB558-treated islets respond to illumination with λ = 560 nm by increasing insulin secretion (**P<0.01 and NS, non-significant versus Con; one-way ANOVA). (b) Incubation with JB558 for 1 hr did not adversely alter cell viability versus dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), as assessed by the ratio of calcein (live):propidium iodide (dead) fluorescence (positive control; Triton X-100) (NS, non-significant versus Con; one-way ANOVA). (c) Representative images of islets stained with calcein and propidium iodide. In all cases, n = 36 islets per treatment group from 6 animals. Values represent mean ± s.e.m.

The data presented here outline a synthetic route for the production of AzoSulfonylureas with red-shifted photochromism. Consistent with its sulfonylurea backbone, JB558 was able to bind SUR1 and activate Epac2A. Formation of cis-JB558 occurred with green-yellow light (λ = 520–561 nm), and thermal back relaxation in the dark yielded trans-JB558. While photoconversion between cis- and trans- forms was rapid in solution, it was slower in the tissue setting, taking minutes for reisomerisation. An effect of Fluo-2 excitation on the isomer equilibrium cannot be excluded, although illumination at λ = 491 nm per se was unable to evoke Ca2+ rises in both Fluo-2- and Fura2 (λ = 340 nm/380 nm)-loaded islets (Fig. S4).

A more plausible explanation is the wind-up of Epac2A-mediated beta cell signalling cascades17, which may outlast JB558 inactivation. Such tissue effects may be desirable for the development of photopharmaceuticals, since pulsed illumination would reduce phototoxicity, while sustaining compound activity to match long-lasting (dozens of minutes) insulin peaks.4 Indeed, JB558 displayed almost 3-fold more potency than its blue-light activated predecessor JB253,6 most likely due to slower back-relaxation during the light pulses used in the secretion assays.

Neither were we able to detect photoswitching of K+ currents in HEK293T cells overexpressing KATP channels, free from orthogonal wavelengths (Fig. S5). This was likely because HEK293T cells do not express sufficient Epac2A to allow JB558 to properly toggle KATP activity,13, 15, 18 and/or the inability to deliver sufficient illumination using the non-coherent source on our patch-clamp setup (ε520 nm (JB558) = 1.14 x 105 mol-1 cm-1; see SI).

Nonetheless, we clearly show that JB558 light-dependently binds Epac2A, allowing optical control of cell function and insulin secretion with λ = 560 nm in the most physiologically-relevant testbed, viz the islets of Langerhans. Thus, JB558 represents a blueprint for red-shifted AzoSulfonylureas based upon heterocyclic azobenzenes. Further studies are now warranted to improve isomerisation kinetics in tissue to improve the use of JB558 as a research tool for rapid KATP channel manipulation. Importantly, similar synthetic approaches may also be applicable to other clinically-relevant azobenzene-possessing compounds where steric bulk may not be well-tolerated e.g. neuromodulators,19 neurotransmitters,20, 21 enzymes22 and antibiotics. 23

Supplementary Material

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [details of any supplementary information available should be included here]. See DOI: 10.1039/c000000x/

Acknowledgments

† J.B. was supported by a European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes (EFSD) Albert Renold Young Scientist Fellowship and a Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes PhD studentship. N.R.J. was supported by a Diabetes UK RW and JM Collins Studentship (12/0004601). J.A.F. was supported by a Collaborative Research Centre Grant (SFB1032). G.A.R. was supported by Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator (WT098424AIA), MRC Programme (MR/J0003042/1), Diabetes UK Project Grant (11/0004210) and Royal Society Wolfson Research Merit Awards. D.T. was supported by an Advanced Grant from the European Research Commission (268795). D.J.H. was supported by a Diabetes UK R.D. Lawrence Research Fellowship (12/0004431). The work leading to this publication has received support from the Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking under grant agreement n° 155005 (IMIDIA), resources of which are composed of a financial contribution from the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) and EFPIA companies’ in kind contribution (G.A.R.).

References

- 1.Rutter GA. Mol Aspects Med. 2001;22:247–284. doi: 10.1016/s0098-2997(01)00013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forbes JM, Cooper ME. Physiol Rev. 2013;93:137–188. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00045.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolen S, Feldman L, Vassy J, Wilson L, Yeh HC, Marinopoulos S, Wiley C, Selvin E, Wilson R, Bass EB, Brancati FL. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:386–399. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-6-200709180-00178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seino S, Shibasaki T, Minami K. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2118–2125. doi: 10.1172/JCI45680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Velema WA, Szymanski W, Feringa BL. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:2178–2191. doi: 10.1021/ja413063e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broichhagen J, Schönberger M, Cork SC, Frank JA, Marchetti P, Bugliani M, Shapiro AMJ, Trapp S, Rutter GA, Hodson DJ, Trauner D. Nat Commun. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/ncomms6116. 5116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frangioni JV. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:626–634. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bakker A, Smith B, Ainslie P, Smith K. Applied Aspects of Ultrasonography in Humans. InTech; 2012. Near-Infrared Spectroscopy. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kienzler MA, Reiner A, Trautman E, Yoo S, Trauner D, Isacoff EY. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:17683–17686. doi: 10.1021/ja408104w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rullo A, Reiner A, Reiter A, Trauner D, Isacoff EY, Woolley GA. Chem Commun (Camb) 2014;50:14613–14615. doi: 10.1039/c4cc06612j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beharry AA, Sadovski O, Woolley GA. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:19684–19687. doi: 10.1021/ja209239m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herbst KJ, Coltharp C, Amzel LM, Zhang J. Chem Biol. 2011;18:243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang CL, Katoh M, Shibasaki T, Minami K, Sunaga Y, Takahashi H, Yokoi N, Iwasaki M, Miki T, Seino S. Science. 2009;325:607–610. doi: 10.1126/science.1172256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rutter GA, Hodson DJ. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;72:453–467. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1755-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Almahariq M, Mei FC, Cheng X. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2014;25:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aguilar-Bryan L, Clement JPt, Gonzalez G, Kunjilwar K, Babenko A, Bryan J. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:227–245. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.1.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leech CA, Chepurny OG, Holz GG. Vitam Horm. 2010;84:279–302. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381517-0.00010-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsalkova T, Mei FC, Li S, Chepurny OG, Leech CA, Liu T, Holz GG, Woods VL, Jr, Cheng X. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:18613–18618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210209109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stein M, Middendorp SJ, Carta V, Pejo E, Raines DE, Forman SA, Sigel E, Trauner D. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:10500–10504. doi: 10.1002/anie.201205475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Volgraf M, Gorostiza P, Numano R, Kramer RH, Isacoff EY, Trauner D. Nat Chem Bio. 2006;2:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nchembio756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tochitsky I, Banghart MR, Mourot A, Yao JZ, Gaub B, Kramer RH, Trauner D. Nat Chem. 2012;4:105–111. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Broichhagen J, Jurastow I, Iwan K, Kummer W, Trauner D. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53:7657–7660. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Velema WA, van der Berg JP, Hansen MJ, Szymanski W, Driessen AJ, Feringa BL. Nat Chem. 2013;5:924–928. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.