Abstract

Whilst Zn2+ ions are critical regulators of many fundamental cellular processes, methods to monitor the free concentrations of these ions dynamically within living cells are presently limited. We have developed a series of genetically-encoded Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)-based sensors that display a large ratiometric change upon Zn2+ binding, have affinities that span the pico- to nanomolar range, and can readily be targeted to subcellular organelles. These sensors reveal that the free cytosolic Zn2+ concentration of fibroblasts and pancreatic islet β-cells is tightly buffered at ~400 pM, a level at least 103-fold lower than that in secretory granules.

Introduction

Transition metals pose an interesting dilemma for living organisms as they are essential cofactors for numerous enzymes and proteins, but at the same time very toxic in their free form1. Mechanisms to control this delicate balance may vary for different metal ions, and also between organisms. Copper homeostasis in eukaryotes has been shown to involve specific copper chaperone proteins that transfer Cu+ to various cellular targets without releasing it into the cytosol2. Similar chaperones have not been identified for Zn2+; instead a general Zn2+ buffering mechanism has been proposed in which the free cytosolic Zn2+ concentration in mammalian cells is kept constant at pM-nM levels3,4. The free concentration of transition metal ions is also likely to differ substantially between subcellular locations, as mM concentrations of total Zn2+ have been reported for pancreatic β cell granules5 and inferred for secretory vesicles in neuronal6 and mast cells7.

Current knowledge of transition metal homeostasis is based mostly on in vitro biochemical characterization of its protein components such as metal importers and exporters, metallochaperones and metal-regulated transcription factors. The affinities of the latter have been used to argue that the free concentration of Zn2+ in E. coli should be ~1 fM8, while the concentration of free Cu+ in yeast was estimated to be 10-18 M2. In order to progress our understanding of transition metal homeostasis and its involvement in diseases, tools are required that allow direct (sub)cellular imaging of transition metal concentrations in single living cells in real time. In recent years an impressive variety of Zn2+ sensitive fluorescent dyes (such as Zinquin, rhodzin-3 and FluoZin-3) have been developed, some of which have also been applied to monitor Zn2+ fluctuations in living cells9,10. However, synthetic probes come with a few intrinsic limitations, notably a lack of full control over subcellular localization and the need to achieve high intracellular concentrations of the dye which may perturb free levels of Zn2+. In addition, it has proven challenging to create synthetic dyes that rival the affinity and specificity typically observed with metalloproteins, which is important to reliably determine the extremely low concentrations of Zn2+ and other transition metal ions4,11,12.

The power of recombinant targeted probes has been well-established in the Ca2+ signaling field, using bioluminescent proteins such as aequorin13 or spectrally-shifted variants of GFP engineered to include suitable binding motifs. In particular, the development of Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)-based sensor proteins has allowed accurate monitoring of Ca2+ fluxes, from the subcellular level to entire organisms, and from the subsecond timeframe to a period of weeks14–16. While some progress has been reported in developing similar FRET-based sensor proteins for Zn(II)12,17,18, at present these sensors have not allowed imaging of free Zn2+ levels in mammalian cells.

Here we report the development of genetically-encoded sensor proteins that for the first time are capable of accurately and dynamically reporting on the extremely low concentration of Zn2+ in the cytosol of single mammalian cells in real time. A new FRET-sensor concept based on conformational switching was introduced to increase the ratiometric response of a previously reported Zn2+ sensor by six-fold. The Zn2+ affinity of this sensor was then systematically attenuated to yield sensor variants with Kd-values between 2 pM and 3 nM. Using this array of sensors proved essential to accurately measure the concentration of free Zn2+ in the cytoplasm of HEK293 cells. Through the incorporation of a suitable targeting sequence into the corresponding cDNAs, these tools were subsequently used to gain specific insights into zinc homeostasis within the cytosol and secretory granule of a specialized secretory cell type, the pancreatic β-cell, where Zn2+ is required for insulin storage19 and has been implicated in controlling hormone release20.

Results

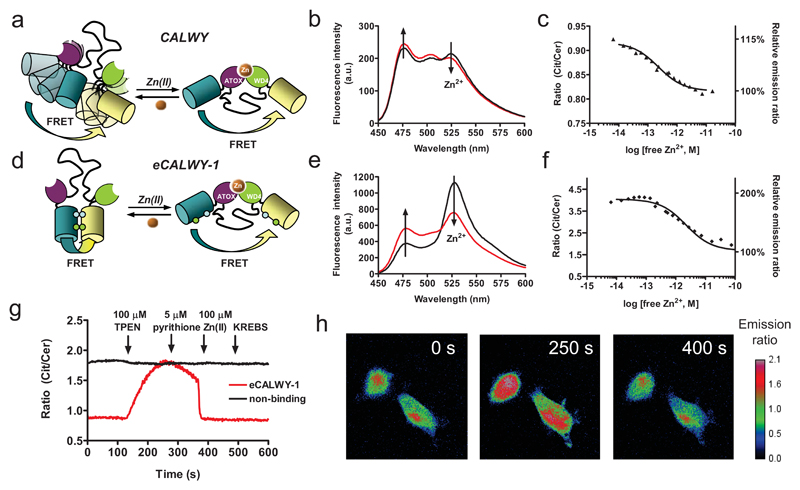

A FRET-based Zn2+ sensor based on conformational switching

We previously reported the development of a genetically encoded FRET-based Zn2+ sensor (CALWY) that consists of two metal binding domains (ATOX1 and WD4) linked via a long flexible peptide linker, with enhanced cyan and yellow fluorescent protein (ECFP and EYFP, respectively) flanking the two metal binding domains (Figure 1a)12. This sensor displayed a very high Zn2+ affinity (Kd = 0.23 pM at pH 7.1). However, like many other genetically-encoded FRET sensors this probe displayed only a small ratiometric response, with a ~15 % decrease in emission ratio upon Zn2+ binding (Figure 1b,c). Our analysis showed that this small change was caused by the presence of a distribution of conformations in the Zn2+-free state whose average energy transfer efficiency was only slightly higher than the amount of energy transfer in the Zn2+-bound state12. Recently we demonstrated that introduction of two mutations, S208F and V224L, can promote formation of a weak intramolecular complex between two fluorescent domain present in a single fusion protein resulting in a substantial increase in energy transfer efficiency21. Following replacement of ECFP and EYFP by Cerulean and Citrine, the same mutations were introduced in the CALWY sensor yielding enhanced CALWY-1 (eCALWY-1). This variant indeed displayed a much higher emission ratio, and thus much more efficient energy transfer, in the unbound state (Figure 1d-f). Addition of Zn2+ resulted in a two-fold decrease in emission ratio, representing an improvement of the dynamic range of the sensor output of 600%. Importantly, the Zn2+ affinity of eCALWY-1 (Kd = 2 pM at pH 7.1) was only 10-fold lower than that of the wild-type sensor, showing that the intramolecular interaction between the fluorescent domains was subtle and easily disrupted by Zn2+ binding. Independent evidence for the proposed conformational switching mechanism depicted in Figure 1d was obtained from fluorescence anisotropy measurements that showed an increase in rotational tumbling of the Citrine domain upon Zn2+ binding (Supplementary Methods, Figure S4).

Figure 1. Design and properties of eCALWY-1, a genetically-encoded Zn2+ sensor based on conformational switching.

Schematic representation of the CALWY (a) and eCALWY-1 (b) sensors. Introduction of S208F and V224L mutations fluorescent domains results in large increase in the ratiometric response. Emission spectra of CALWY (c) and eCALWY-1 (d) before (black line) and after (red line) addition of 0.9 mM Zn2+ in 1 mM HEDTA (b) or EGTA (e). Zn2+ titrations of CALWY (c) and eCALWY-1 (f), showing the ratio of yellow and cyan emission (R527/475) as a function of Zn2+ concentration using 420 nm excitation. The solid lines depict fits assuming single binding events with Kd’s of 0.22 and 2 pM for CALWY and eCALWY-1, respectively. Measurements were performed using ~ 1 µM protein in 150 mM Hepes, 100 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, pH 7.1 at 20 ºC. (g) Response of single HEK293 cells expressing either eCALWY-1 or a non-binding variant (eCALWY-NB) to Zn2+ depletion and addition as measured by the ratio of Citrine and Cerulean emission. Cells were perfused with KB buffer (0 s), KB buffer containing 50 μM TPEN (120 s), 5 μM pyrithione (240 s), 5 μM pyrithione/100 μM Zn(II) (360 s) and KB buffer (480 s). (h) False-colored fluorescence ratio micrographs of HEK293 cells expressing eCALWY-1 after 0, 250, and 400 s of the experiment described in (g).

To test whether eCALWY-1 was able to detect changes in free cytosolic Zn2+ levels, we monitored the Cerulean and Citrine emission in single HEK293 fibroblasts using fluorescence microscopy. A two-fold increase in emission ratio was observed after perifusion with 50 μM of the membrane permeable zinc chelator N,N,N’,N’-tetrakis-(2-pyridylmethyl)-ethylenediamine (TPEN) for cells expressing eCALWY-1 (Figure 1g,h), consistent with a decrease in the cytosolic free Zn2+ concentration. Subsequent perifusion with 5 μM of the zinc ionophore pyrithione had a minor effect, but exposure of the cells to 100 μM ZnCl2 and 5 μM pyrithione resulted in a strong decrease in emission ratio. Since the emission ratio obtained after saturation with Zn2+ was identical to the ratio at the start of the experiment, we concluded that eCALWY-1 was already fully saturated in cells under the normal culture conditions. No changes in emission ratio were observed when TPEN or zinc and pyrithione were added to cells expressing a non-binding variant of eCALWY that lacked the metal-binding cysteines, confirming that Zn2+ binding was responsible for the changes observed for eCALWY-1 (Figure 1g).

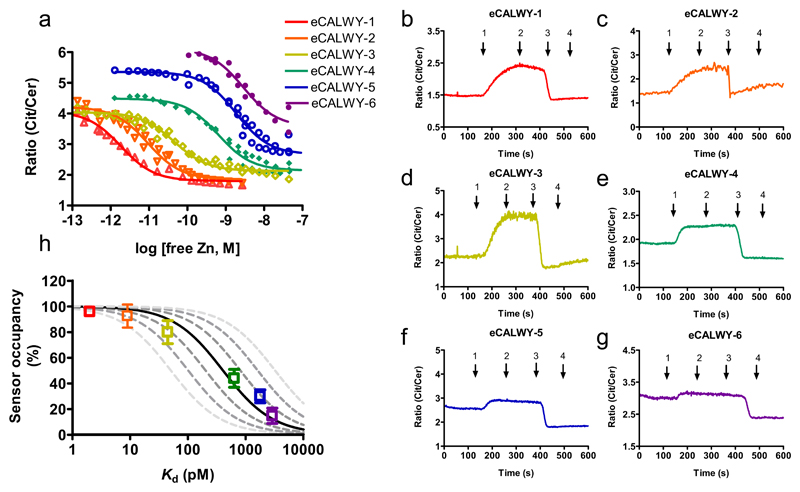

Determination of free Zn2+ levels using a toolbox of zinc sensors

Since the eCALWY-1 sensor was shown to be saturated with Zn2+ in HEK293 cells under normal culture conditions, we next developed a series of weaker eCALWY variants covering a range of Zn2+ concentrations. Two complementary strategies were employed to systematically tune the Zn2+ affinity of eCALWY-1. A single cysteine-to-serine mutation in the metal binding site of the WD4 domain was found to attenuate the Zn2+ affinity 300-fold, yielding the eCALWY-4 sensor with a Kd of 600 pM. Further fine-tuning of the Zn2+ affinity was achieved by shortening the flexible peptide linker between the metal binding domains of eCALWY-1 and eCALWY-4 from 9 to either 5 (eCALWY-2 and eCALWY-5) or 3 GGSGGS repeats (eCALWY2 and eCALWY-6). As reported previously for the original CALWY sensors, shortening of the peptide linker resulted in 3-10 fold lower Zn2+ affinities (Table 1, Figure 2a)12. All sensor variants displayed a two-fold change in emission ratio, while their Kd’s together spanned three orders of magnitude.

Table 1. Sensor properties of eCALWY variants.

| Variant | Number of GGGSGGS repeats in linker |

Mutationa | Ratiometric change (%)b |

Kd (Zn2+) (pM)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| eCALWY-1 | 9 | - | 230 | 1.8 ± 0.5 |

| eCALWY-2 | 5 | - | 230 | 9 ± 3 |

| eCALWY-3 | 3 | - | 190 | 45 ± 11 |

| eCALWY-4 | 9 | C416S | 210 | 630 ± 160 |

| eCALWY-5 | 5 | C416S | 200 | 1850 ± 600 |

| eCALWY-6 | 3 | C416S | 170 | 2900 ± 1000 |

The numbering refers to that of the eCALWY sequence. This mutation involves the 2nd cysteine in the MTCXXC motif of the WD4 domain.

Ratiometric change is defined as the emission ratio in the absence of Zn2+ divided by the emission ration in the Zn2+ bound state.

Kd values were determined in 150 mM Hepes, 100 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM DTT pH 7.1. Errors show the 95% confidence intervals obtained from non-linear fits. More information is available in Supplementary Methods.

Figure 2. Determination of cytosolic free Zn2+ concentration in HEK293 cells using a toolbox of eCALWY variants.

(a) Citrine over Cerulean emission ratio versus free zinc concentration for the different eCALWY variants. Solid lines represent fits assuming a single binding event with the Kd’s listed in Table 1. (b-g) Responses of single HEK293 cells expressing eCALWY-1-6 to a protocol of KREBS buffer with 50 μM TPEN (1), 5 μM pyrithione (2), 5 μM pyrithione/100 μM Zn(II) (3) or no additives (4). (h) Sensor occupancy in HEK293 cells as a function of the sensor Kd. Datapoints show the occupancy of the different eCALWY variants as determined from the traces in Supplementary Figure S5 using equation 1, error bars indicate the standard deviation. The solid line represents the expected response to a free cytosolic zinc concentration of 400 pM. The dashed lines depict the expected responses assuming free zinc concentrations of 50, 100, 200, 800, 1600, and 3200 pM, respectively.

Figures 2b-g show the responses of all six eCALWY variants transiently expressed in HEK293 cells to a protocol of TPEN addition followed by Zn2+/pyrithione treatment (see also Video S1). The responses observed for each sensor correlate well with their in vitro determined Kd. The emission ratio at the start of experiment showed a consistent trend changing from the Zn2+-saturated level for eCALWY-1 to the Zn2+-depleted level for eCALWY-6. A substantially faster equilibration upon TPEN addition was observed for the weaker sensor variants, probably reflecting an increase in Zn2+ dissociation rate caused by the C416S mutation. The occupancy of the sensor at the start of the experiment was calculated using equation 1, in which Rmax and Rmin are the steady-state ratios obtained after TPEN and zinc/pyrithione addition, respectively, and Rstart is the ratio at the start of the experiment.

| (1) |

A plot of the sensor occupancy as a function of its Kd shows a clear sigmoidal shape, that is best described by assuming a free Zn2+ concentration of ~400 pM (Figure 2h). The plot also shows the predicted occupancies assuming different values of free Zn2+ and illustrates that the free Zn2+ concentration in HEK293 cells is buffered between 200 and 800 pM. Importantly, the fact that the occupancies of the entire sensor series can be described by a single concentration of free Zn2+ suggests that the intracellular free Zn2+ concentration is not significantly disturbed by the presence of the sensor.

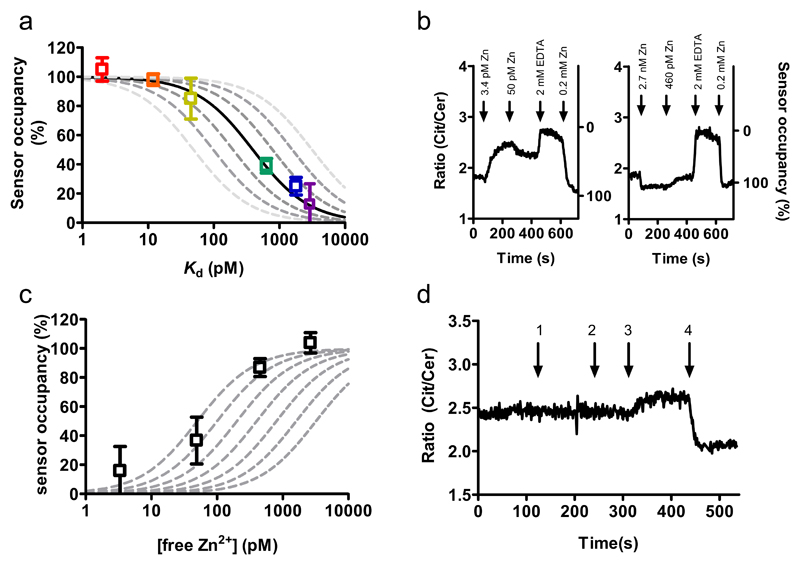

Cytosolic Zn2+ homeostasis in pancreatic β-cells

Insulin-containing secretory vesicles present in pancreatic β-cells are known to store tens of millimolar concentrations of Zn2+ ions5 which are required to store insulin in a hexameric form19. To test whether Zn2+ transport into secretory vesicles would lower the steady-state cytosolic Zn2+ levels, we determined free Zn2+ in clonal rat pancreatic β-cells (INS-1(832/13)) cells22 using the same approach as described above for HEK293 cells. The responses of the various sensor variants in INS-1(832/13) cells, which contain abundant secretory vesicles, were found to be very similar to those in HEK293 cells. A plot of sensor occupancy versus sensor Kd’s yielded again a free Zn2+ concentration of ~400 pM, suggesting that this value may be relatively invariable among different mammalian cell types (Figure 3a).

Figure 3. Monitoring cytosolic free Zn2+ concentration in pancreatic β-cells.

(a) Sensor occupancy in INS-1(832/13) cells as a function of the sensor Kd. Datapoints show the occupancy of the different eCALWY variants as determined from the traces in Supplementary Figure S6 using equation 1. The solid line represents the expected response to a free cytosolic zinc concentration of 400 pM. The dashed lines depict the expected responses assuming free zinc concentrations of 50, 100, 200, 800, 1600, and 3200 pM, respectively. (b) Citrine over Cerulean emission ratio of a permeabilized INS-1(832/13) cell expressing eCALWY-4 perfused with intracellular buffer containing various amounts of free zinc, followed by perifusion with 2 mM EDTA and 0.2 mM Zn(II). (c) Occupancy of the eCALWY-4 sensor as a function of the free zinc concentration in permeabilized INS-19832/13. The dashed lines show the expected responses for Kd values of 50, 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 and 3200 pM, respectively. (d) Ratiometric response of an INS-1(832/13) cell expressing eCALWY-4 upon perifusion with KREBS buffer with 25 mM KCl (1), regular KREBS (2), 50 μM TPEN (3) and 5 μM pyrithione/100 μM Zn2+ (4).

The determination of intracellular free Zn2+ concentration assumes that the Zn2+ affinity of the sensor in the cell is similar to that of the purified protein studied in vitro. To verify whether the Zn2+ affinity of eCALWY was affected by intracellular conditions such as macromolecular crowding or interactions with endogenous proteins, an intracellular calibration was performed in clonal INS-1(832/13) cells expressing eCALWY-4. Cells were permeabilized for 30 s using S. aureas α-toxin to create 3 kDa sized pores that allow free ion exchange between buffer and cytosol, but prevent proteins from leaking out.23 Subsequently, cells were perifused with a buffer containing physiologically relevant free magnesium and calcium ion levels (0.35 mM and 100 nM, respectively) and different concentrations of free zinc ions (Figure 3b). In each experiment, cells were exposed to two different concentrations of free Zn2+, followed by excess EDTA and excess ZnCl2. Using the latter two conditions to determine the minimum and maximum emission ratios, the occupancy of the eCALWY-4 sensor was calculated at four different free zinc concentrations using equation 1. Although a plot of the sensor occupancy as a function of free Zn2+ concentration suggest a slightly lower intracellular Kd of 100-200 pM (Figure 3c), this calibration nonetheless confirms that the Zn(II) affinity of eCALWY-4 is not significantly affected by the intracellular environment.

We next determined whether cytosolic free Zn(II) concentrations may change during the stimulation of β cells with secretagogues since it is conceivable that Zn2+ co-released with insulin may re-enter the cells via Zn2+ uptake mechanisms (including members of the zinc importer, ZiP family)3. Free cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations in β-cells increase from ~100 nM to ~500 nM or ~1 μM upon stimulation with elevated glucose or KCl concentrations, respectively, due to plasma membrane depolarization (caused by the closure of ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the case of glucose) and the opening of voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels24. No changes in the free Zn2+ concentration were observed upon addition of 20 mM glucose (not shown) or 25 mM KCl (Figure 3d) to INS-1(832/13) cells expressing the eCALWY-4 sensor that had been starved overnight with 3 mM glucose, however. The KCl responsiveness of the cells was confirmed when the same experiment was performed with cells expressing eCALWY-4 and loaded with the Ca2+ dye Fluo-3, as shown by the expected spike and oscillations in calcium levels (Figure S7). These observations suggest that cytosolic Zn2+ levels are not easily disturbed by external stimuli or by large changes in the concentrations of other divalent metal ions including Ca2+.

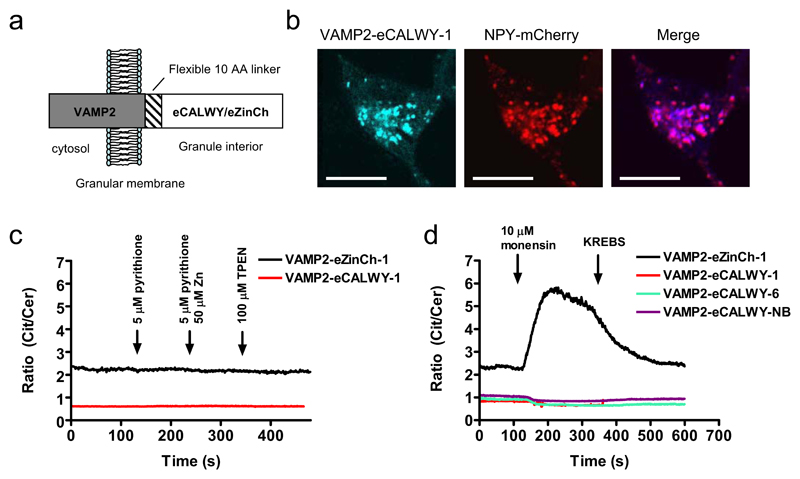

Vesicular targeting of Zn2+ probes

An important advantage of the use of genetically-encoded probes for measuring intracellular ion concentrations is the capacity to address these probes to specific intracellular domains through the incorporation of specific targeting motifs13,15,24,25. Having established the potency of the eCALWY sensors to probe Zn2+ concentrations in the cytosol, we next explored whether these probes could be targeted to other intracellular organelles with a potentially important role in Zn2+ homeostasis. Sensors targeted to insulin-containing granules of β-cells were generated by fusion to the C-terminus of the vesicle associated membrane protein 2 (VAMP2), a protein previously used to target aequorin to the granule matrix in β-cells (Figure 4a)25. Colocalization studies with a granule-localised neuropeptide Y-mCherry fusion protein26 by confocal microscopy showed that VAMP2-eCALWY-1 and VAMP2-eCALWY-6 proteins were indeed exclusively localized to insulin-containing granules (Figure 4b; Figure S10). Both VAMP2-eCALWY-1 and VAMP2-eCALWY-6 showed a low emission ratio, suggesting that both were fully saturated at ambient intragranular Zn2+ concentrations (Figure 4c,d). The emission ratio of VAMP2-eCALWY-1 did not respond to the addition of either TPEN or ZnCl2 and pyrithione, however. While this could mean that the eCALWY sensors were not functional when targeted to granules, it is more likely that insufficient TPEN was able to cross the granular membrane to significantly lower the granular free Zn2+ concentration. To test this hypothesis, we targeted another genetically-encoded Zn2+ sensor, eZinCh-1, to the granules as a VAMP2 fusion protein. This previously reported sensor has a relatively weak Zn2+ affinity (Kd = 1 μM at pH 7.1 and 250 μM at pH 6.0; Supplementary Fig, S8), but displays a four-fold increase in emission ratio upon Zn2+ binding in vitro17. Again, no changes in emission ratio were observed upon perifusion with TPEN or zinc and pyrithione (Figure 4c), but a large ratiometric increase was observed after the addition of monensin (Figure 4d; supplementary video S2). Monensin is a known Na+/H+ exchanger that increases the pH of granules from ~ pH 6.0 to cytosolic levels (~pH 7.1)25. This increase in pH is expected not only to increase the Zn2+ affinity of eZinCh, but also to release Zn2+ ions by the dissolution of the insulin/Zn2+ complexes27. TPEN addition after the monensin treatment had no further effect, confirming that TPEN is not able to significantly reduce granular free Zn2+ levels (data not shown). From these results, we conclude that the eCALWY sensors are most likely saturated with Zn2+ within dense core vesicles under normal conditions, whereas the eZinCh-1 sensor is mostly Zn2+-free. These data therefore suggest that the free Zn2+ concentration in the vesicles lies between 1 and 100 μM based on the in vitro-determined affinities of these sensors at pH 6.0 (Figure S8 and S9).

Figure 4. Subcellular targeting of Zn2+ probes to insulin-storing granules.

(a) Scheme showing the structural orientation of VAMP2-eCALWY and VAMP2-eZinCh-1 with respect to the granular membrane. (b) Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) images of INS-1(832/13) cells cotransfected with VAMP2-eCALWY-1 and NPY-mCherry. The VAMP2-eCALWY-1 emission was obtained using excitation at 420 nm, while excitation at 595 nm was used to image NPY-mCherry. The scale bar represents 10 μm. (c) Ratiometric response of INS-1(832/13) cells expressing VAMP2-eZinCh-1 (black line) or VAMP2-eCALWY-1 (red line) to perifusion with 5 μM pyrithione (120 s), 50 μM Zn(II)/ 5 μM pyrithione (240 s) and 100 μM TPEN (360 s), all in KB medium. (d) Ratiometric response of INS-1(832/13) cells expressing different VAMP2-eCALWY variants or VAMP2-eZinCh-1 to perifusion with 10 μM monensin (120 s), followed by regular KB buffer (240 s).

Discussion

The genetically-encoded sensors reported here offer several key advantages compared to the synthetic fluorescent dyes that are typically used for studying cellular Zn2+ homeostasis: (1) control over subcellular localization and the absence of leakage; (2) a relatively large ratiometric response that is independent of sensor concentration; (3) a high and tunable affinity covering a range between 10-9 and 10-12 M, and (4) ready delivery to cells by simple transfection protocols. Moreover, our results suggest that promoting intramolecular domain interactions could be a generic, rational design strategy to improve the dynamic response of FRET-based sensors, which is an important prerequisite to extent their application to high throughput methods such as fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS)28.

The availability of sensors covering a range of Zn2+ affinities proved critical to reliably determine the cytosolic Zn2+ concentration. An important potential problem with measuring intracellular metal concentrations is that the presence of the sensor perturbs the free metal concentration. This is particularly true in this case where the free metal concentration of ~400 pM (corresponding to ~100 free Zn2+ ions per cell) is 103-104 fold lower than that of the sensor protein. Two observations indicate that the free Zn2+ concentration was not significantly affected, however. First, the occupancies of the sensor proteins were found to be independent of the expression level. More importantly, the occupancies of all six eCALWY variants were well described by their Kd values and a single free Zn2+ concentration. If the sensors had perturbed the free Zn2+ concentration substantially one would expect lower occupancies for the high affinity sensors than observed here.

The free Zn2+ concentration of ~400 pM reported here is similar to the 600 pM that was recently reported by Maret and coworkers using the fluorescent dye FluoZin-34. However, its relatively low affinity for Zn2+ (Kd = 15 nM) renders FluoZin-3 suboptimal for measuring subnanomolar concentrations. In addition, this probe probably does not exclusively report the cytosolic Zn2+ concentration, having a strong tendency to accumulate in intracellular organelles including secretory vesicles (GAR, unpublished observations). Using a sensor based on fluorescently-labeled carbonic anhydrase11, Bozyme et al reported a significantly lower free Zn2+ concentration of 5 pM in PC12 cells by comparing the absolute emission ratio measured in the cell directly to an in vitro calibration curve. We observed significant variability in the absolute emission ratio among cells that expressed the same fluorescent sensor, however, probably as a result of variation in the contribution of background fluorescence. In our hands, reliable estimation of the free Zn2+ concentration therefore always required measurement of the emission ratios corresponding to 0 % and 100 % sensor occupancy.

The observation that the cytosolic free Zn2+ concentration is similar in two substantially different mammalian cell types (fibroblastic and secretory), suggests that cytosolic Zn2+ levels are carefully controlled and might not vary much between different mammalian cell types. Moreover, the demonstration that cytosolic free Zn2+ concentrations did not change in β-cells under conditions in which cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations fluctuated considerably provides evidence both for the selectivity of the reporters in situ, and for the view that the concentrations of these two metal ion species can be regulated entirely independently. Maret and coworkers29 recently showed that metallothioneines can provide robust Zn2+ buffering in the range between 10-11 and 10-9 M, which nicely coincides with the ~400 pM of free Zn2+ obtained in this study. Intriguingly, cytosolic Zn2+ concentrations are thus maintained at a level that is sufficient to fully saturate native Zn2+ proteins (which typically show Kd’s of 1-10 pM)30, but approximately 10-fold below the low nM concentrations that have been reported to be inhibitory to certain cytosolic proteins.

In conclusion, we have developed a new generation of Zn2+ probes that, delivered using simple plasmid transfection protocols, can be used as a convenient means of detecting and imaging low cytosolic free Zn2+ concentrations dynamically and in real time in living cells. Importantly, we demonstrate that these probes are molecularly targetable to subcellular organelles, including the secretory granule. The availability of this new sensor toolbox is expected to allow much more detailed studies of Zn2+ homeostasis in a variety of organelles and a wide range of cell types, including the identification of new proteins involved in maintaining Zn2+ homeostasis and the possibility to more directly assess the role of transition metal homeostasis in health and disease3.

Methods

Intracellular FRET imaging

Cells were imaged by using an Olympus IX-70 (Melville, NY) microscope fitted with a monochromator (Polychrome IV, TILL Photonics, Grafelfing, Germany) and a MAGO charge-coupled device camera (TILL Photonics) controlled by TILLVISION software (TILL Photonics). For FRET measurements, a 455DRLP dichroic mirror (Chroma Technology, Brattleboro, NY) and two emission filters (D465/30 for Cerulean and D535/30 (Chroma) for Citrine) alternated by a filter changer (Lambda 10–2, Sutter Instruments, San Rafael, CA) were used. Images were acquired at 1 Hz using a 100 ms exposure time and a 433 nm excitation wavelength.

Cells were imaged in modified Krebs–Hepes/bicarbonate (KB) buffer, consisting of 132.5 mM NaCl, 3.6 mM KCl, 0.5 mM NaH2PO4, 0.5 mM MgSO4, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 10 mM Hepes, 2 mM NaHCO3 and 3 mM glucose and was then preequilibrated with 95:5 O2:CO2, pH 7.4. TPEN and pyrithione were prepared fresh on the day of use in 25 mM and 1 mM stock solutions in DMSO, respectively. Buffers were added using perifusion (2 mL/min) with KB plus additions as stated (37 ºC). Where indicated, cells were permeabilized by adding 20 μl of 250 μg/ml α-toxin dissolved in intracellular buffer (IB) to 100 μl of INS-1(832/13) cells in IB. IB comprised 140 mM KCl, 10 mM KH2PO4 2 mM MgSO4, 1 mM ATP, 2 mM Na+ succinate, 20 mM Hepes, and 5.5 mM glucose and was then pre-equilibrated with 95:5 O2:CO2, pH 7.05. After 30 s of incubation with α-toxin, perifusion was used to incubate the cells in fresh IB (2 mL/min). Next, cells were exposed to IB containing different amounts of Ca2+, Mg2+, Zn2+ that were buffered using combinations of EGTA and EDTA or HEDTA (Table S4).

Supplementary Material

Note: Supplementary information is available.

Acknowledgements

We thank S.M.J. van Duijnhoven for the expression and characterization of eZinCh-1, Dr. A. McDonald for assisting in the co-localization studies, Dr. A. Tarasov for setting up the α-toxin incubation, Prof. H. Bayley (University of Oxford) for kindly providing the α-toxin and Dr Chris Newgard (Duke University) for the provision of INS-1(832/13) cells. We also thank Dr L. Klomp and P. van den Berghe (University Medical Center Utrecht) for their support in early stages of this research. MM and MSK acknowledge support by the Human Frontier of Science Program (HPSF Young Investigator Grant, (RGY)0068-2006). GAR thanks the National Institutes of Health for Project grant RO1 DK071962-01, the Wellcome Trust for Programme grants 067081/Z/02/Z and 081958/Z/07/Z, the MRC (UK) for Research Grant G0401641, and the EU FP6 (“SaveBeta” consortium grant). TJN and EAB were supported by Imperial College Divisional Studentships.

Footnotes

Author contributions

J.L.V., G.A.R and M.M. designed research; J.L.V., T.J.N., E.A.B., M.S.K. conducted experiments, J.L.V., T.J.R., E.A.B, M.S.K., G.A.R. and M.M. analyzed data, and J.L.V., G.A.R. and M.M. wrote the paper.

Literature

- 1.Valko M, Morris H, Cronin MT. Metals, toxicity and oxidative stress. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12:1161–1208. doi: 10.2174/0929867053764635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rae TD, Schmidt PJ, Pufahl RA, Culotta VC, O'Halloran TV. Undetectable intracellular free copper: the requirement of a copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase. Science. 1999;284:805–808. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cousins RJ, Liuzzi JP, Lichten LA. Mammalian zinc transport, trafficking, and signals. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24085–24089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krezel A, Maret W. Zinc-buffering capacity of a eukaryotic cell at physiological pZn. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2006;11:1049–1062. doi: 10.1007/s00775-006-0150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutton JC, Penn EJ, Peshavaria M. Low-molecular weight constituents of isolated insuline-secretory granules- bivalent-cations, adenine-nucleotides and inorganic phosphates. Biochem J. 1983;210:297–305. doi: 10.1042/bj2100297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linkous DH, et al. Evidence hat the ZnT3 protein controls the total amount of elemental zinc in synaptic vesicles. J Histochem Cytochem. 2008;56:3–6. doi: 10.1369/jhc.6A7035.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho LH, et al. Labile zinc and zinc transporter ZnT4 in mast cell granules: Role in regulation NF-KB translocation. J Immunology. 2004;172 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7750. 77507760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Outten CE, O'Halloran TV. Femtomolar sensitivity of metalloregulatory proteins controlling zinc homeostasis. Science. 2001;292:2488. doi: 10.1126/science.1060331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Domaille DW, Que EL, Chang CJ. Synthetic fluorescent sensors for studying the cell biology of metals. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:168–175. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nolan EM, Lippard SJ. Small-molecule fluorescent sensors for investigating zinc metalloneurochemistry. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:193–203. doi: 10.1021/ar8001409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bozym RA, Thompson RB, Stoddard AK, Fierke CA. Measuring picomolar intracellular exchangeable zinc in PC-12 cells using a ratiometric fluorescence biosensor. ACS Chem Biol. 2006;1:103–111. doi: 10.1021/cb500043a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Dongen EMWM, et al. Variation of linker length in ratiometric fluorescent sensor proteins allows rational tuning of Zn(II) affinity in the picomolar to femtomolar range. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:3494–3495. doi: 10.1021/ja069105d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rizzuto R, Simpson AWM, Brini M, Pozzan T. Rapid changes of mitochrondrial Ca2+ revealed by specifically targeted recombinant aequorin. Nature. 1992;358:325–327. doi: 10.1038/358325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mank M, et al. A genetically encoded calcium indicator for chronic in vivo two-photon imaging. Nat Methods. 2008;5:805–811. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyawaki A, et al. Fluorescent indicators for Ca2+ based on green fluorescent proteins and calmodulin. Nature. 1997;388:882–887. doi: 10.1038/42264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallace DJ, et al. Single-spike detection in vitro and in vivo with a genetic Ca2+ sensor. Nat Methods. 2008;5:797–804. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evers TH, Appelhof MAM, de Graaf-Heuvelmans PTHM, Meijer EW, Merkx M. Ratiometric detection of Zn(II) using chelating fluorescent protein chimeras. J Mol Biol. 2007;374:411–425. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qiao W, Mooney M, Bird AJ, Winge DR, Eide DJ. Zinc binding to a regulatory zinc-sensing domain monitored in vivo by using FRET. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:8674–8679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600928103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dodson G, Steiner D. The role of assembly in insulin's biosynthesis. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1998;8:189–194. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sladek R, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies novel risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2007;445:881–885. doi: 10.1038/nature05616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vinkenborg JL, Evers TH, Reulen SW, Meijer EW, Merkx M. Enhanced sensitivity of FRET-based protease sensors by redesign of the GFP dimerization interface. ChemBioChem. 2007;8:1119–1121. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hohmeier HE, et al. Isolation of INS-1-erived cell lines with robust ATP-sensitive K+ channel-dependent and independent glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2000;49:424–430. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tarasov AI, Girard CA, Ashcroft FM. ATP sensitivity of the ATP-sensitive K+ channel in intact and permeabilized pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes. 2006;55:2446–2454. doi: 10.2337/db06-0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rutter GA, et al. Stimulated Ca2+ influx raises mitochrondrial free Ca2+ to supramicromolar levels in a pancreatic beta-cell line. Possible role in glucose and agonist-induced insuline secretion. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22385–22390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell KJ, et al. Dense core secretory vesicles revealed as a dynamic Ca(2+) store in neuroendocrine cells with a vesicle-associated membrane protein aequorin chimera. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:41–51. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200103145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsuboi T, Rutter GA. Multiple forms of "kiss-and-run" exocytosis revealed by evanescent wave microscopy. Curr Biol. 2003;13:563–567. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hutton JC. The internal pH and membrane potential of the insulin-secretory granule. Biochem J. 1982;204:171–178. doi: 10.1042/bj2040171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ouyang M, Sun J, Chien S, Wang Y. Determination of hierarchical relationship of Src and Rac at subcellular locations with FRET biosensors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:14353–14358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807537105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krezel A, Maret W. Dual nanomolar and picomolar Zn(II) binding properties of metallothionein. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:10911–10921. doi: 10.1021/ja071979s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krezel A, Maret W. Thionein/metallothionein control Zn(II) availability and the activity of enzymes. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2008;13:401–409. doi: 10.1007/s00775-007-0330-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.