Abstract

Background

Urban birth and urban living are associated with increased risk of schizophrenia but less is known about effects on more common psychotic experiences (PEs). China has undergone the most rapid urbanization of any country which may have affected the population-level expression of psychosis. We therefore investigated effects of urbanicity, work migrancy, and residential stability on prevalence and severity of PEs.

Methods

Population-based, 2-wave household survey of psychiatric morbidity and health-related behavior among 4132 men, 18–34 years of age living in urban and rural Greater Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China. PEs were measured using the Psychosis Screening Questionnaire.

Results

1261 (31%) of young men experienced at least 1 PE. Lower levels of PEs were not associated with urbanicity, work migrancy or residential stability. Urban birth was associated with reporting 3 or more PEs (OR: 1.63; 95% CI: 1.25–2.11), after multivariable adjustment, with further evidence (P = .01) this effect was restricted to those currently living in urban environments (OR: 1.78; 95% CI: 1.16–2.72). Men experiencing a maximum of 5 PEs were over 8 times more likely to have been born in an urban area (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 8.81; 95% CI 1.50–51.79).

Conclusions

Men in Chengdu, China, experience a high prevalence of PEs. This may be explained by rapid urbanization and residential instability. Urban birth was specifically associated with high, but not lower, severity levels of PEs, particularly amongst those currently living in urban environments. This suggests that early and sustained environmental exposures may be associated with more severe phenotypes.

Keywords: urban birth, urban living, work migrancy, psychotic experiences

Introduction

Social adversity and living in urban locations are associated with increased rates of psychotic illness.1 Links have been observed between schizophrenia and urban birth,2 urban upbringing,3 and urban residence in temporal proximity to illness presentation4 but less is known about associations with psychotic experiences (PEs).5 PEs are relatively common in the general population and thought to be on a continuum with psychotic symptoms in clinical samples.6 Associations between urbanicity and psychosis are far from new. Historical data suggest increases in incidence of schizophrenia in all western countries during the 19th century which coincided with the industrial revolution,7–9 a period of rapid urbanization and industrialization coupled with mass population displacement from rural to urban areas. This hypothesis suggests that risk factors associated with urban living10 may result in increased incidence, and could result in increased prevalence of PEs in such locations. Because persistence of PEs and later development of psychotic disorder correspond to prevalence of PEs measured at baseline,11–13 stressors associated with abrupt displacement to an urban environment could affect both the population and clinical expression of psychosis phenotypes.

Contemporary naturalistic studies in populations undergoing rapid industrialization, urbanization, and rural-urban migration may allow us to test whether and why rates of psychotic illness and PEs increase during periods of major socioeconomic transformation. No previous study has investigated effects of both urban birth and internal work migrancy on clinical psychosis and PEs within a country undergoing rapid urban development. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has undergone the most rapid process of urbanization of any country from the mid-20th century onwards and the prevalence of (detected) schizophrenia is thought to be increasing.14 Persons recorded as living in urban areas increased from 13% to 53% between 1952 and 2012, with rural-urban labor migration providing the backbone for long-term economic transformation. Chinese migrant workers, however, experience considerable acculturative stress,15 social marginalization16 and individual-level risks for poor mental health,17–19 although specific associations with psychosis have not been confirmed. Previous surveys have observed that prevalence of schizophrenia is high in Chinese urban areas,20,21 but studies investigating effects of population displacement, rural-urban migration, and birth on heterogeneity in these rates are missing.

We conducted a large representative survey of PEs among young adult men in Sichuan Province, PRC. The aims of the study were to investigate whether: (1) urban birth and living were associated with increased prevalence of PEs; (2) being a migrant worker modified effects of birth and current residence; and (3) effects of place of birth, living, migrancy, and residential stability differed across severity of PEs.

Methods

Participant Sampling

We carried out a survey of men aged 18–34 years in 2 waves in 2011 and 2013, based on stratified multistage sampling to correspond to a previous UK survey22 to achieve a representative sample of Chinese men living in rural and urban settings in Sichuan province, PRC. This method was preferred given the absence of a simple sampling frame. First, we stratified Greater Chengdu into 3 concentric rings delineating (1) the city centre (exclusively urban “districts”); (2) suburbs (mixed rural “counties” and urban “districts”); and (3) rural areas (exclusively rural “counties”). Our sampling strategy varied according to concentric ring (strata) and administrative organization of households.

Total numbers of selected households in urban and rural areas were 1152 and 1260, respectively. Different districts and villages were included randomly in the 2 waves, without replacement, to avoid duplication of any district being sampled more than once. All sampling frames were derived using official data provided by the Chengdu Government website (http://jcpt.chengdu.gov.cn/chengdushi/).

Data Collection

A self-administered questionnaire used in a previous UK survey22 was adapted and translated into Mandarin. The questionnaire was then back-translated into English before final modifications for usage. Informed consent was obtained from all survey respondents. Respondents completed pencil and paper questionnaires in privacy and were given gifts to the value of 50 yuan for participation.

Ethical approval to carry out the survey was obtained from the Medical Ethics Committee of the University of Sichuan.

Survey Measures

The Psychosis Screening Questionnaire (PSQ)23 assessed 5 common PEs: hypomania, thought interference, paranoid delusions, strange experiences, and auditory and visual hallucinations. We reported descriptive statistics (ie, prevalence) on those endorsing 1 or more, 3 or more or all 5 PEs. To examine the associations between severity of PEs and exposure and other survey variables, we treated PEs as both a nominal (0, 1–2, 3–4, 5 PEs) and binary variable (3–5 vs 0–2); the latter represented our previously used cut-off to indicate potentially clinically relevant psychosis.22

Questions from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV personality disorder (SCID-II) screening questionnaire24 probed for antisocial personality disorder. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)25 identified anxiety and depressive disorder based on scores of ≥11 in the past week. The psychometric properties of the Mandarin version of the HADS have been previously found to be good.26 Scores of ≥20 on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT),27 and ≥25 on the Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT),28 were used to identify alcohol or drug dependence respectively. The AUDIT tool demonstrated good psychometric properties in Mandarin-speaking samples.29 The DUDIT had not previously been assessed in a Mandarin-speaking sample, but we followed recommendations from the authors for translation (http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/best-practice/eib/dudit).

Participants were asked about lifetime history of suicidal attempts, consultations with a medical practitioner for mental health problems, and impairment in daily living.

Exposure Variables

All participants were asked about place of birth and whether this was a rural or urban area; this is formally defined under the household registration section of PRC. They were asked about the urban/rural status of their current living location, length of time in current location (in years, as a marker of residential instability) spent there, and whether they were a migrant worker.

Statistical Analysis

To ensure a sample representative of the region, weights were constructed based on probabilities of circle, district, street, and community. All descriptive statistics and subsequent statistical comparisons are based on weighted data using survey commands in Stata 14. To examine the association between exposures, other survey variables and PEs, we used logistic regression for our binary outcome (0–2 vs 3–5 PEs) and multinomial logistic regression for nominal data (0, 1–2, 3–4, 5 PEs), with no PEs as reference group. Results were presented with adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% CIs. Statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

Demography and Sampling

The combined weighted sample included 4132 men, 18–34 years of age, 2867 in the first and 1265 in the second wave. Of the total sample, 2853 (69.3%) reported rural birth and 1262 (30.7%) urban birth; 2104 (51.2%) current rural living, and 2005 (48.8%) current urban living; 1604 (40.4%) reported they were migrant workers. Median time spent in current location was 0.5 years (IQR 0.2–1.7). For descriptive purposes, we used the conventional cut-off of the last quartile (at least 1.7 years) as the threshold to define long time period at current location. In regression models, we included time at current location as continuous measure to increase power in detecting effects of this exposure variable.

Urban-born men were younger, and more likely to be single, completed higher education, misused alcohol and drugs, and consulted a medical practitioner than those born in rural areas (table 1). However, urban-born men reported lower levels of depression than their rural-born counterparts. Men currently living in an urban area were also more likely to be single, to have completed higher education, and were less likely to be depressed than those living in a rural area. No associations were found between work migrancy and demography. Finally, shorter length of time living in current location was associated with younger age, lower educational level, single marital status, ethnic minorities, and history of suicide attempts.

Table 1.

Univariable Associations of Urbanicity and Migrancy Characteristics With Demography, Psychotic Experiences, and Other Psychiatric Morbidity

| Urbanicity and Migrancy Characteristics | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban Birth | Urban Living | Migrant Worker | Time at Current Location (Ordinal) | |||||||||

| n | % | AOR (95% CI) | n | % | AOR (95% CI) | n | % | AOR (95% CI) | n a | %a | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Demography | ||||||||||||

| Single marital status | 782 | 62.0 | 1.71 (1.27–2.29)*** | 1162 | 58.0 | 1.49 (1.04–2.14)* | 890 | 55.5 | 1.13 (0.96–1.33) | 278 | 32.7 | 0.39 (0.31–0.50)*** |

| Higher education level | 568 | 46.2 | 2.61 (2.12–3.20)*** | 906 | 46.0 | 4.17 (2.73–6.37)*** | 504 | 32.4 | 1.11 (0.85–1.43) | 182 | 21.8 | 0.77 (0.61–0.98)* |

| Ethnic minority | 44 | 3.5 | 1.52 (0.93–2.47) | 65 | 3.2 | 1.57 (0.61–4.04) | 53 | 3.3 | 1.44 (0.53–3.90) | 9 | 1.1 | 0.48 (0.29–0.80)** |

| Age—mean (SD) | 25.1 | 4.8 | 0.96 (0.93–0.98)*** | 25.6 | 4.6 | 0.98 (0.95–1.01) | 26.1 | 4.6 | 1.02 (1.00–1.05) | 28.2 | 4.2 | 1.09 (1.06–1.13)*** |

| Other psychiatric morbidity | ||||||||||||

| Depressive disorder | 128 | 10.3 | 0.63 (0.41–0.97)* | 166 | 8.4 | 0.39 (0.25–0.61)*** | 198 | 12.5 | 0.81 (0.58–1.12) | 118 | 14.0 | 1.02 (0.78–1.33) |

| Anxiety disorder | 126 | 10.1 | 1.14 (0.74–1.75) | 214 | 10.8 | 1.44 (1.01–2.05)* | 170 | 10.8 | 1.31 (0.96–1.79) | 47 | 5.6 | 0.76 (0.64–0.90)** |

| Alcohol misuse | 124 | 10.2 | 1.96 (1.32–2.91)** | 148 | 7.6 | 1.25 (0.80–1.98) | 105 | 6.8 | 0.96 (0.71–1.30) | 55 | 6.7 | 0.79 (0.52–1.19) |

| Drug misuse | 28 | 2.3 | 2.94 (1.66–5.20)*** | 28 | 1.4 | 1.31 (0.80–2.16) | 22 | 1.4 | 1.22 (0.60–2.48) | 6 | 0.7 | 0.87 (0.53–1.40) |

| Suicide attempt | 110 | 9.4 | 1.08 (0.75–1.56) | 190 | 9.8 | 1.25 (0.87–1.80) | 153 | 10.1 | 1.26 (0.81–1.97) | 55 | 6.8 | 0.65 (0.435–1.19) |

| Antisocial personality disorder | 62 | 5.0 | 1.21 (0.88–1.68) | 95 | 4.8 | 1.18 (0.92–1.50) | 68 | 4.3 | 0.93 (0.45–1.92) | 33 | 4.0 | 0.87 (0.51–1.51) |

| Psychotic experiences (1+) | 396 | 32.0 | 1.03 (0.87–1.22) | 605 | 30.6 | 0.93 (0.66–1.30) | 508 | 32.2 | 1.05 (0.87–1.27) | 196 | 23.4 | 0.69 (0.54–0.88)** |

| Psychotic experiences (3+) | 91 | 7.4 | 1.90 (1.28–2.82)** | 132 | 6.7 | 2.05 (1.46–2.88)*** | 89 | 5.6 | 1.24 (0.68–2.26) | 18 | 9.9 | 0.38 (0.19–0.74)** |

| Impairment in daily living | 19 | 1.5 | 1.15 (0.96–1.38) | 23 | 1.2 | 1.07 (0.83–1.39) | 23 | 1.5 | 1.18 (1.04–1.34)* | 13 | 1.6 | 0.83 (0.61–1.12) |

| Consulted medical practitioner | 71 | 5.9 | 2.09 (1.04–4.17)* | 75 | 3.9 | 1.01 (0.60–1.69) | 60 | 3.9 | 1.00 (0.65–1.53) | 14 | 1.7 | 0.42 (0.24–0.71)** |

Note: AOR, adjusted odds ratios for survey wave. All estimates are based on weighted data.

For descriptive purposes absolute and relative frequencies of the last quartile were reported, the continuous score was used for ordinal regression.

P < .05

P < .01

P < .001.

Prevalence and Distribution of PEs by Exposure Status

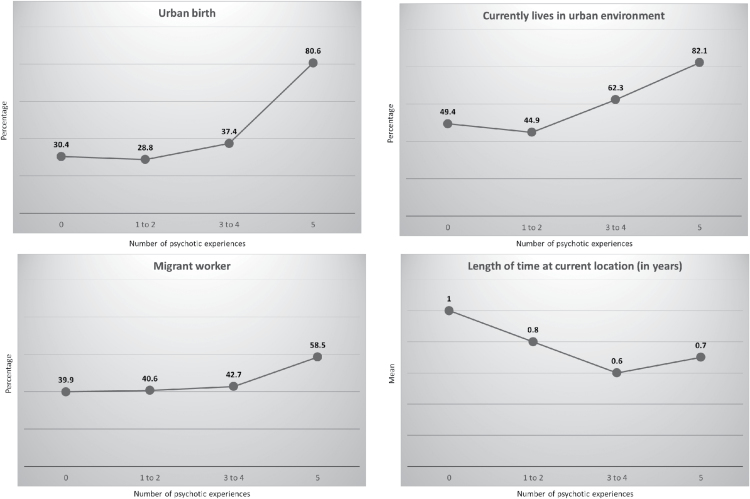

In the total sample, 1261 (31.1%; 95% CI: 25.8%–37.0%) described experiencing 1 or more PEs within the last year, with an annual prevalence of people screening positive for psychosis (PSQ ≥ 3) of 5.0% (95% CI: 3.7%–6.7%). Initial inspection suggested prevalence of 1 or more PEs did not vary by urban birth, current living or migrancy status (table 1). Length of time at current location was associated with prevalence of 1 or more PEs, such that greater residential stability was associated with a lower likelihood of PEs (AOR: 0.69; 0.54–0.88). By contrast, prevalence of 3 or more PEs was associated with urban birth (AOR: 1.90; 1.28–2.82), urban living (AOR: 2.05; 1.46–2.88), and time at current location (AOR: 0.38; 0.19–0.74). Further inspection of this data (figure 1) suggested that the proportion of people exposed to urban birth, current living and migrant status increased with greater endorsement of PEs, particularly amongst participants endorsing all 5 PEs. Residential instability (indicated by decreasing length of time at current location) showed a linear association with number of PEs, although this was not sustained at 5 PEs. There was also some evidence of a synergistic relationship between urban birth and current urban living, such that most men with 5 PEs (79.4%) were exposed to both variables (supplementary figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of urbanicity/migrancy across different levels of psychotic experiences.

Association Between PEs and Other Clinical and Demographic Characteristics

Table 2 shows associations between levels of PEs, demography and other psychiatric morbidity. There were no significant associations between demography and levels of PEs. However, men who reported an increasing number of PEs were more likely to receive comorbid diagnoses of anxiety disorder, alcohol and drug misuse, antisocial personality disorder, although not depressive disorders; they were also more likely to report both impairment in daily living and consulting a medical practitioner due to mental health problems. These patterns were present across all levels of PEs, including when considering 3 or more PEs as a cut-off for clinical symptoms.

Table 2.

Univariable Associations Between Psychotic Experiences and Demographic and Clinical Variables

| Number of Psychotic Experiences | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (Ref.) (2789, 68.9%) | 1–2 (1058, 26.1%) | 3–4 (167, 4.1%) | 5 (36, 0.9%) | 3–5a | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | AOR | n | % | AOR | n | % | AOR | AOR | |

| Demography | ||||||||||||

| Single marital status | 1394 | 50.0 | 621 | 58.7 | 1.35 (1.09–1.68)** | 102 | 61.3 | 1.53 (0.74–3.17) | 20 | 57.0 | 1.27 (0.44–3.63) | 1.36 (0.65–2.86) |

| Higher education level | 889 | 32.8 | 292 | 28.3 | 0.79 (0.55–1.12) | 37 | 23.3 | 0.61 (0.26–1.40) | 16 | 44.9 | 1.63 (0.56–4.76) | 0.80 (0.47–1.37) |

| Ethnic minority | 83 | 3.0 | 15 | 1.4 | 0.45 (0.14–1.48) | 9 | 5.1 | 1.74 (0.60–5.10) | 3 | 7.1 | 2.46 (0.47–12.87) | 2.22 (0.83–5.96) |

| Age—mean (SD) | 26.1 | 4.9 | 25.4 | 4.9 | 0.98 (0.94–1.01) | 24.6 | 5.3 | 0.94 (0.89–1.00)* | 23.5 | 4.4 | 0.89 (0.77–1.03) | 0.94 (0.90–0.97)** |

| Other psychiatric morbidity | ||||||||||||

| Depressive disorder | 356 | 12.9 | 165 | 15.8 | 1.27 (0.78–2.08) | 28 | 17.4 | 1.43 (0.43–4.69) | 2 | 4.8 | 0.34 (0.06–2.12) | 1.12 (0.41–3.08) |

| Anxiety disorder | 125 | 4.5 | 154 | 14.6 | 3.49 (2.31–5.25)*** | 72 | 43.6 | 16.07 (7.91–32.62)*** | 18 | 50.6 | 21.20 (10.82–41.52)*** | 10.26 (4.81–21.87)*** |

| Alcohol misuse | 133 | 4.9 | 87 | 8.5 | 1.81 (1.22–2.68)** | 48 | 29.3 | 8.06 (4.05–16.04)*** | 6 | 15.9 | 3.68 (1.49–9.08)** | 5.87 (3.02–11.40)*** |

| Drug misuse | 24 | 0.9 | 20 | 1.9 | 2.29 (0.90–5.79) | 3 | 1.8 | 2.18 (0.85–5.60) | 4 | 11.1 | 14.59 (5.20–40.94)** | 3.14 (1.21–8.10)* |

| Suicide attempt | 141 | 5.3 | 122 | 12.0 | 2.45 (1.78–3.39)*** | 69 | 43.2 | 13.66 (7.55–24.69)*** | 10 | 29.1 | 7.37 (0.49–110.28) | 8.85 (6.13–12.78)*** |

| Antisocial personality disorder | 85 | 3.1 | 64 | 6.1 | 2.03 (1.56–2.64)*** | 20 | 12.0 | 4.27 (2.46–7.39)*** | 4 | 12.3 | 4.37 (0.41–46.41) | 3.34 (1.84–6.08)*** |

| Impairment in daily living | 20 | 0.7 | 20 | 2.0 | 1.62 (1.35–1.95)*** | 4 | 2.2 | 2.80 (2.29–3.42)* | 11 | 31.5 | 3.91 (2.06–7.41)*** | 2.48 (1.87–3.28)*** |

| Consulted medical practitioner | 71 | 2.7 | 44 | 4.4 | 1.57 (0.50–4.94) | 19 | 11.8 | 4.64 (2.08–10.35)*** | 12 | 33.3 | 17.43 (9.18–33.08)** | 5.54 (3.33–9.12)*** |

Note: AOR, adjusted for survey wave. All estimates are based on weighted data.

Versus 0–2 PEs.

P < .05

P < .01

P < .001.

Regression Modeling

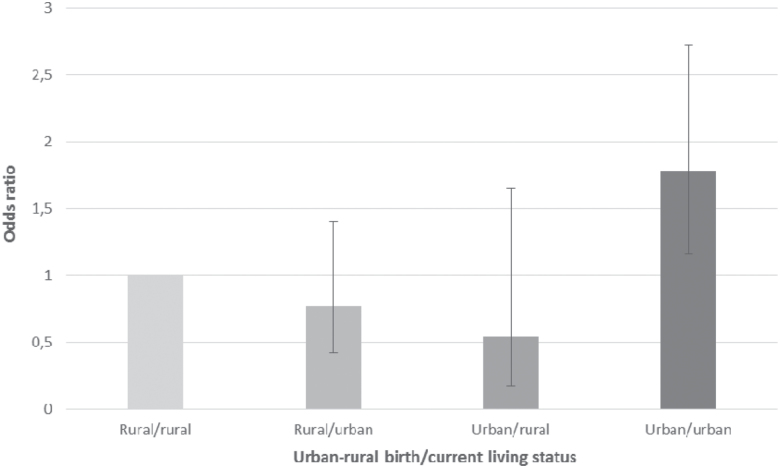

We found no associations between migrant worker status and PEs (table 3). Current urban living was initially associated with reporting 5 PEs (Models I and II, table 3), but this effect was attenuated following mutual adjustment for urban birth and other exposures including age, anxiety disorder, alcohol misuse, drug use, suicide attempt, and antisocial personality disorder (Model III). Men who reported experiencing all 5 PEs were 8.81 (95% CI: 1.50–51.79) times more likely to have been born in an urban area than men reporting no PEs, after multivariable adjustment. Similar patterns were observed when we considered 3 or more PEs as an indicator for possible clinical psychosis (table 3). Thus, after adjustment for all other variables (Model III) we found urban birth was associated with increased odds of reporting 3 or more PEs (OR: 1.63; 1.25–2.11), with weak evidence that greater residential stability was associated with reduced odds of psychosis (OR: 0.76; 0.58–1.01; P = .056). We found evidence to support a synergistic effect between urban birth and current living, with excess risk limited to those exposed to both variables (OR: 1.78; 1.16–2.72; P = .01; figure 2).

Table 3.

Effects of Urbanicity, Migrancy, and Residential Stability on Number of Psychotic Experiences Following Multivariable Regression

| Number of Psychotic Experiences | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 | 3–4 | 5 | 3–5a | |||||||||

| AOR | 95% CI | P | AOR | 95% CI | P | AOR | 95% CI | P | AOR | 95% CI | P | |

| Model I | ||||||||||||

| Urban birth | 0.88 | 0.73–1.07 | .180 | 1.27 | 0.55–2.96 | .547 | 8.57 | 1.49–49.48 | .020 | 1.80 | 1.22–2.65 | .006 |

| Currently lives in urban environment | 0.80 | 0.55–1.16 | .215 | 1.63 | 1.01–2.63 | .046 | 4.51 | 0.83–24.43 | .015 | 2.02 | 1.44–2.84 | .001 |

| Migrant worker | 1.03 | 0.77–1.38 | .810 | 1.15 | 0.57–2.31 | .667 | 2.31 | 0.28–19.10 | .409 | 1.29 | 0.70–2.39 | .384 |

| Time at current location in years | 0.81 | 0.64–1.02 | .070 | 0.59 | 0.39–0.89 | .016 | 0.76 | 0.46–1.25 | .261 | 0.66 | 0.49–0.89 | .002 |

| Model II | ||||||||||||

| Urban birth | 0.90 | 0.74–1.10 | .277 | 1.21 | 0.47–3.12 | .673 | 8.80 | 1.22–63.55 | .033 | 1.84 | 1.23–2.75 | .006 |

| Currently lives in urban environment | 0.73 | 0.46–1.16 | .167 | 1.56 | 0.78–3.15 | .193 | 3.81 | 0.70–20.73 | .112 | 2.04 | 1.27–3.28 | .006 |

| Migrant worker | 0.99 | 0.69–1.43 | .974 | 0.97 | 0.53–1.78 | .924 | 2.26 | 0.24–21.22 | .448 | 1.17 | 0.60–2.27 | .626 |

| Time at current location in years | 0.83 | 0.64–1.09 | .169 | 0.60 | 0.41–0.86 | .009 | 0.76 | 0.45–1.30 | .291 | 0.68 | 0.51–0.91 | .014 |

| Model III | ||||||||||||

| Urban birth | 1.07 | 0.82–1.40 | .573 | 1.08 | 0.47–2.51 | .770 | 8.81 | 1.50–51.79 | .020 | 1.63 | 1.25–2.11 | .001 |

| Currently lives in urban environment | 0.73 | 0.47–1.15 | .163 | 0.90 | 0.47–1.73 | .734 | 2.20 | 0.39–12.50 | .348 | 1.18 | 0.77–1.80 | .417 |

| Migrant worker | 0.92 | 0.58–1.47 | .701 | 0.85 | 0.55–1.32 | .443 | 2.08 | 0.09–45.81 | .620 | 1.05 | 0.41–2.65 | .917 |

| Time at current location in years | 0.75 | 0.51–1.11 | .135 | 0.59 | 0.41–0.85 | .008 | 1.17 | 0.21–6.62 | .850 | 0.76 | 0.58–1.01 | .056 |

Note: All estimates are based on weighted data. Reference group: no psychotic experiences. Model I: adjusted for survey wave and age. Model II: further adjusted for anxiety disorder, alcohol misuse, drug use, suicide attempt and antisocial personality disorder. Model III: further adjusted for other urbanicity/ migrancy characteristics.

Versus 0–2 PEs.

Fig. 2.

Combined effect of urban-rural birthplace and current living status on experience of 3 or more psychotic experiences (PEs). Chinese men born in urban areas and living in urban areas at the time of the survey had elevated odds of experiencing 3 or more PEs compared with men born and living in rural areas. No other differences in risk were observed. Wald P value for interaction: P = .01. Model adjusted for age, anxiety disorder, alcohol misuse, drug use, suicide attempt, antisocial personality disorder, migrant status, time resident in current area and survey wave. Three or more PEs on PSQ has been previously used to define the presence of clinically relevant psychosis. d: number of people endorsing 3+ PEs; N: total sample; AOR: adjusted odds ratio.

Discussion

The annual prevalence of 1 or more PEs in this sample of young Chinese men was high. This suggests that young Chinese men may have been exposed to more risk factors than elsewhere, including the marked social and economic changes in China. When we investigated this in relation to urban birth, current living status, and work migrancy, we found evidence that men who reported experiencing 3 or more PEs were 63% more likely to have been born in urban than rural areas, after adjustment for several possible confounders. We also found evidence to suggest that this excess was restricted to men who were born and remained living in urban areas at the time of the survey. For men reporting all 5 PEs, urban birth was associated with over an 8-fold elevation in risk.

Urban birth was also independently associated with alcohol and drug misuse. Surprisingly, urban living and residential stability, as measured by length of time in current location, were not generally associated with other psychiatric morbidity, although residential instability was associated with reported suicide attempts. The negative associations we observed between urbanicity and depression correspond to the higher prevalence consistently observed in rural areas in China.30 Linear relationships between increasing levels of PEs and all forms of psychiatric morbidity, except depression, correspond to studies showing that PEs in western countries are explained substantially by other conditions and that most individuals with PEs have current diagnoses primarily of mood or anxiety, but also substance misuse and self-harm.31 Despite previous studies showing associations between work migrancy and poor mental health, we found no associations in this study.

Urban Birth and Urban Living

In our study, urban birth was a stronger predictor of more severe PEs than urban living, though we found some evidence that persistent exposure to urban environments was associated with greatest risk. We found little evidence to suggest that either exposure was associated with lower levels of PEs in our sample of Chinese men. This suggests that, in this population, factors associated with urban birth and living are not associated with the extended psychosis phenotype, which is thought to lie on a continuum with clinical psychosis in the general population.6,32 In contrast, we found that urban birth was associated with more severe psychotic conditions, represented by both our definition of 3 or more PEs in the past year, as well as endorsement of all 5 PEs measured using the PSQ. These results are consistent with previous studies which suggest that urban birth is associated with clinical psychosis,33 but weaker for subclinical PEs.1 In our study, reporting of more PEs was strongly associated with greater impairment and medical consultations, indicative of a categorical psychosis construct. Although our cross-sectional method could not ultimately determine whether transition had progressively occurred from PEs to a clinical psychotic state,12,13 an ongoing process of transition from lower levels over time was unlikely due to lack of associations observed between urban birth and lower levels of PEs in our sample.

The Effects of Work Migrancy and Residential Instability

We did not find independent associations between migrancy status and PEs, but there was weak evidence (P = .056) that shorter time in current location (whether urban or rural) was associated with a higher likelihood of reporting 3 or more PEs. China’s migrant worker population reached 211 million in 2009 (National Health and Family Planning Commission of PRC; http://en.nhfpc.gov.cn/) and the mental health status of migrants is considered generally poorer, particularly among those who move between cities17 and become unemployed.34 Rural-to-urban migrants experience stressful living conditions and social stigma which interferes with reconstruction of social capital.35 Shorter time in current location, rather than migrant status per se, may therefore correspond to difficulty re-establishing protective effects against PEs; alternatively shorter time in current location could be a result of PEs and associated psychopathology (reverse causation). However, our lack of observed associations between PEs, other psychiatric morbidity, and work migrancy may have been due to bias inherent in cross-sectional studies of migrants: sick and unhealthy migrants are observed to return to their home towns and villages leading to general overestimate of the health status of rural-urban migrants.36 Additionally, migrant workers in the Chengdu region may have experienced better mental health, observed elsewhere, associated with economic mobility and improved opportunities.37

Strengths and Limitations

Our study should be considered in light of its strengths and limitations. Although we used a self-report instrument assessing only 5 symptoms, these are central to the diagnosis of psychosis, have good face validity, and are likely to be strongly associated with other symptoms in the syndrome of psychosis. While our results indicate that 2 definitions of more severe psychosis pathologies (endorsement of 3 or more, or all 5 PEs) was associated with urban birth, future epidemiological studies in countries such as China should incorporate detailed, comprehensive assessments of clinical psychosis outcomes to understand whether urban birth is a marker of increased risk of psychotic disorder vs subclinical PEs in the general population. Because we were unable to confirm whether participants with more severe phenotypes in our study had clinical psychosis using research diagnostic interviews, it was necessary to rely on indicators of discontinuity across this population,33 self-reported clinical impairment, and medical consultations. Longitudinal or repeated cross-sectional surveys, which include female participants, are essential in future investigations, since they could assess whether incidence of psychotic disorders in such countries increases as a function of industrialization and economic transformation.

The survey took place in Chengdu area (Western Central China), where we used back-translated assessments of exposure, outcome and other variables. Despite our efforts to obtain census data from China to compare our sample’s demographic characteristics to corresponding census data from this area of China or other areas of China, this was not possible. On the other hand, we believe that the information we obtained to create weights ensures that the weighted sample was (to the best of our knowledge) representative of the population of interest.

Finally, the large, representative sample allowed us to test associations at the population level and important interactions between risk factors. Nonetheless, despite our large sample size, our survey reported a low prevalence of 5 PEs (0.9%), resulting in some wide CIs associated with this group. Further, larger multi-site studies will be necessary to obtain more precise estimates. In attempting to measure effects on severity, we were unable to include long-stay patients in hospitals because inpatients were not included in the survey. Nevertheless, PRC has relatively fewer psychiatric beds compared to the US and European countries, and there is greater expectation that support will be provided by families.38

Implications

Psychotic disorders are increasingly seen as symptomatic expressions of more than 1 disease process, with different aetiologies leading to the same presentation. Our study findings are new and suggest 2 different disease processes leading to PEs in our sample. Firstly, the extended psychosis phenotype along a continuum with clinical psychosis, closely associated with other conditions, including anxiety and substance misuse, where stressful environmental factors are thought to have interacted with genetic risk.32 Our findings support emerging evidence that PEs may be highly prevalent among young Chinese men.39 This may be due to the relatively young age of our sample, given the robust peak in psychotic disorder for men at this age.40 We discourage comparisons of our findings with other international prevalence estimates30 because few studies have used comparable designs, sampling strategies or instruments to assess PEs. One exception is a comparison with a parallel survey we have conducted in a sample of young men in the UK to estimate PEs using the PSQ. Here, we have shown that young Chinese men were nearly 3 times more likely to report 3 or more PEs than their British counterparts (OR: 2.91, 95% CI 1.85–4.57).41 The high 12-month prevalence of any PE reported in our sample coincided with rapid urbanization, and we cannot refute the possibility that dramatic social processes contributed to the substantial prevalence of PEs seen here and elsewhere in Chinese youth.39

Despite this, the association between PEs and urban birth were restricted to greater endorsement of PEs (using either our nominal or binary outcome). Given that most PEs are short-lasting and will not result in more severe psychotic conditions, these results suggest that the effects of urban exposures may be limited to clinical phenotypes. Since urban birth may be a marker for exposure to in utero or early life adversities, further longitudinal studies should now incorporate neuropathological and genetic markers to differentiate the more prevalent, severe clinical condition, with a relatively sudden onset in young adulthood42 and associated with urban birth, from the continuum of PEs in the general population. We found some evidence to suggest that the effect of urban birth on reporting 3 or more PEs was only maintained amongst those still living in an urban area; such synergy potentially supports a role for chronic exposure to social adversities across the life course.

Earlier commentaries on the apparent increase of schizophrenia during the 19th century, coinciding with rapid urbanization, suggested possible key exposures were neurotoxins or infections.7–9 Correspondingly, our study in 21st century China suggests that risk of a distinct form of clinical psychosis is increased among those born in urban environments, whose parents may have witnessed and been part of a rapid social and economic transformation in China from rural to urban populations, who may subsequently have been exposed to new social and environmental adversities associated with urban birth.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data are available at Schizophrenia Bulletin online.

Funding

The study was supported by funding from the East London National Health Service Foundation Trust, UK and the Opening Project of Key Laboratory of Evidence Science (China University of Political Science and Law), Ministry of Education, China (102249). J.B.K. is supported by a Sir Henry Dale Fellowship jointly funded by the Wellcome Trust and the Royal Society (101272/Z/13/Z).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1. Heinz A, Deserno L, Reininghaus U. Urbanicity, social adversity and psychosis. World Psychiatry. 2013;12:187–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mortensen PB, Pedersen CB, Westergaard T et al. . Effects of family history and place and season of birth on the risk of schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:603–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pedersen CB, Mortensen PB. Evidence of a dose-response relationship between urbanicity during upbringing and schizophrenia risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:1039–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sundquist K, Frank G, Sundquist J. Urbanisation and incidence of psychosis and depression: follow-up study of 4.4 million women and men in Sweden. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Newbury J, Arseneault L, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Odgers CL, Fisher HL. Why are children in urban neighborhoods at increased risk for psychotic symptoms? Findings from a UK Longitudinal Cohort Study. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42:1372–1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Verdoux H, van Os J. Psychotic symptoms in non-clinical populations and the continuum of psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2002;54:59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Torrey EF. Schizophrenia and Civilization. New York: Jason Aronson; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hare E. Was insanity on the increase? The fifty-sixth Maudsley Lecture. Br J Psychiatry. 1983;142:439–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hare E. Schizophrenia as a recent disease. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;153:521–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kirkbride JB, Jones PB, Ullrich S, Coid JW. Social deprivation, inequality, and the neighborhood-level incidence of psychotic syndromes in East London. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:169–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Linscott RJ, van Os J. An updated and conservative systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological evidence on psychotic experiences in children and adults: on the pathway from proneness to persistence to dimensional expression across mental disorders. Psychol Med. 2013;43:1133–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van Os J, Linscott RJ, Myin-Germeys I, Delespaul P, Krabbendam L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychosis continuum: evidence for a psychosis proneness-persistence-impairment model of psychotic disorder. Psychol Med. 2009;39:179–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dominguez MD, Wichers M, Lieb R, Wittchen HU, van Os J. Evidence that onset of clinical psychosis is an outcome of progressively more persistent subclinical psychotic experiences: an 8-year cohort study. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:84–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chan KY, Zhao FF, Meng S et al. ; Global Health Epidemiology Reference Group (GHERG) Prevalence of schizophrenia in China between 1990 and 2010. J Glob Health. 2015;5:010410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhong BL, Liu TB, Huang JX et al. . Acculturative stress of Chinese rural-to-urban migrant workers: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wong DFK, Chang YL, He XS. Rural migrant workers in urban China: living a marginalised life. Int J Soc Welfare. 2007;16:32–40. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yang T, Xu X, Li M, Rockett IR, Zhu W, Ellison-Barnes A. Mental health status and related characteristics of Chinese male rural-urban migrant workers. Community Ment Health J. 2012;48:342–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guo Y, Chen X, Gong J et al. . Association between spouse/child separation and migration-related stress among a random sample of rural-to-urban migrants in Wuhan, China. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0154252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lin Y, Zhang Q, Chen W et al. . Association between social integration and health among internal migrants in ZhongShan, China. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0148397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cooper J, Sartorius N. Cultural and temporal variations in schizophrenia: a speculation on the importance of industrialization. Br J Psychiatry. 1977;130:50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Long J, Huang G, Liang W et al. . The prevalence of schizophrenia in mainland China: evidence from epidemiological surveys. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130:244–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Coid JW, Ullrich S, Keers R et al. . Gang membership, violence, and psychiatric morbidity. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:985–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bebbington P, Nayani T. The Psychosis Screening Questionnaire. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1995;5:11–20. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ullrich S, Deasy D, Smith J et al. . Detecting personality disorders in the prison population of England and Wales: comparing case identification using the SCID-II screen and the SCID-II clinical interview. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol. 2008;19:301–322. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang W, Chair SY, Thompson DR, Twinn SF. A psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in patients with coronary heart disease. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18:1908–1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Babor T, Higgins-Biddle J, Saunders J, Monteiro M. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Berman AH, Bergman H, Palmstierna T, Schlyter F. Evaluation of the Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT) in criminal justice and detoxification settings and in a Swedish population sample. Eur Addict Res. 2005;11:22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wu SI, Huang HC, Liu SI et al. . Validation and comparison of alcohol-screening instruments for identifying hazardous drinking in hospitalized patients in Taiwan. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:577–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McGrath JJ, Saha S, Al-Hamzawi A et al. . Psychotic experiences in the general population: a cross-national analysis based on 31,261 respondents from 18 countries. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:697–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McGrath JJ, Saha S, Al-Hamzawi A et al. . The bidirectional associations between psychotic experiences and DSM-IV mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:997–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van Os J, Reininghaus U. Psychosis as a transdiagnostic and extended phenotype in the general population. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:118–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. van Os J, Verdoux H. Diagnosis and classification of schizophrenia: categories versus dimensions, distributions versus disease. In: Murray RM, Jones PB, Sussex E, Os J, Cannon M, eds. The Epidemiology of Schizophrenia. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2003:364–410. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen L, Li W, He J, Wu L, Yan Z, Tang W. Mental health, duration of unemployment, and coping strategy: a cross-sectional study of unemployed migrant workers in eastern China during the economic crisis. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chen X, Stanton B, Kaljee LM et al. . Social stigma, social capital reconstruction and rural migrants in Urban China: a population health perspective. Hum Organ. 2011;70:22–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang L, Liu S, Zhang G, Wu S. Internal migration and the health of the returned population: a nationally representative study of China. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li L, Wang HM, Ye XJ, Jiang MM, Lou QY, Hesketh T. The mental health status of Chinese rural-urban migrant workers: comparison with permanent urban and rural dwellers. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42:716–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tse S, Ran MS, Huang Y, Zhu S. Mental health care reforms in Asia: the urgency of now: building a recovery-oriented, community mental health service in china. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64:613–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sun M, Hu X, Zhang W et al. . Psychotic-like experiences and associated socio-demographic factors among adolescents in China. Schizophr Res. 2015;166:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kirkbride JB, Hameed Y, Ankireddypalli G et al. . The epidemiology of first-episode psychosis in early intervention in psychosis services: findings from the Social Epidemiology of Psychoses in East Anglia [SEPEA] Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:143–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Coid J, Hu J, Kallis C et al. . A cross-national comparison of violence among young men in China and the UK: psychiatric and cultural explanations. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52:1267–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. David AS, Ajnakina O. Psychosis as a continuous phenotype in the general population: the thin line between normality and pathology. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:129–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.