Abstract

Background.

Tuberculous and cryptococcal meningitis (TBM and CM) are the most common causes of opportunistic meningitis in HIV-infected patients from resource-limited settings, and the differential diagnosis is challenging.

Objective.

To compare clinical and basic cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) characteristics between TBM and CM in HIV-infected patients.

Methods.

A retrospective analysis was conducted of clinical, radiological and laboratory records of 108 and 98 HIV-infected patients with culture-proven diagnosis of TBM and CM, respectively. The patients were admitted at a tertiary center in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Logistic regression model was used to distinguish TBM from CM and derive a diagnostic index based on the adjusted odds ratio (OR) to differentiate these two diseases.

Results:

In multivariate analysis, TBM was independently associated with: CSF with neutrophil predominance (OR=35.81, 95% CI 3.80–341.30, P=0.002), CSF pleocytosis (OR=9.43, 95% CI 1.30–68.70, P=0.027), CSF protein >1.0g/l (OR=5.13, 95% CI 1.38–19.04, P=0.032), and Glasgow Coma Scale <15 (OR=3.10, 95% CI 1.03–9.34, P=0.044). Nausea and vomiting (OR=0.27, 95% CI 0.08–0.90, P=0.033) were associated to CM. Algorithm-related area under receiver operating characteristics curve was 0.815 (95% CI: 0.758–0.873, P<0.0001), but an accurate cut-off was not derived.

Conclusion:

Although some clinical and basic CSF characteristics seem to be useful in the differential diagnosis of TBM and CM in HIV-infected patients, an accurate algorithm was not identified. Optimised access to rapid, sensitive and specific laboratory tests is essential.

Keywords: tuberculous meningitis, cryptococcal meningitis, diagnosis, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, Brazil

Introduction

Tuberculous and cryptococcal meningitis (TBM and CM) are the most common causes of opportunistic meningitis in HIV-infected patients.[1–5] TBM and CM share similar clinical and laboratory features, which results in delay of diagnosis and worse outcome, particularly in settings where confirmatory diagnosis is not possible.[6] Clinical algorithms have been proposed to simplify the diagnosis and treatment of these neurologic infections,[6–8] but lack of sensitivity and specificity precludes their implementation in clinical practice.

The objective of this study was to compare clinical and laboratorial findings of TBM and CM in HIV-infected patients to propose an algorithm to differentiate these diseases.

Patients and Methods

We retrospectively analyzed data from the clinical records of 108 and 98 HIV-infected patients with culture-proven diagnosis of TBM or CM. The patients were admitted between March 1999 and June 2008 at the Emilio Ribas Institute of Infectious Diseases, Sao Paulo, Brazil. This hospital is a 250-bed tertiary teaching center and the main referral institution for HIV-infected patients in Sao Paulo State. HIV infection was diagnosed by ELISA and confirmed by Western blot. We evaluated demographic, clinical, radiological and laboratory information. The study was approved by the ethical and scientific boards of the institution.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was obtained by lumbar puncture at hospital admission. Pleocytosis was defined as leukocyte count above 5 cells/μl. The normal range of lumbar CSF glucose is > 2.22 mmol/l (40 mg/dl) and CSF protein < 0.45 g/l (45 mg/dl). Neutrophil pleocytosis was defined as >50% CSF leukocytes.

The comparison between groups (TBM v. CM) was performed using the Mann-Whitney U-test for numeric variables and Yates corrected χ2 or Fisher’s exact-test as appropriate for categorical variables. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% of confidence interval (CI) was adjusted by binary logistic regression model (Wald test) and included diagnosis of TBM v. CM as the dependent variable. Covariates and associated factors with TBM (v. CM) in univariate analysis were included to derive a diagnostic index based in clinical, laboratory, and radiological findings. A receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve was derived to calculate the accuracy of the logistic model. An estimation of cut-off for diagnosis index was made to distinguish between TBM and CM. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05, and SPSS 20.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) software was used for statistical anaylisis.

Results

Table 1 shows a comparison of the clinical, radiological, and laboratory characteristics among HIV-infected patients with TBM and CM. CSF with three abnormal parameters (pleocytosis, protein elevation, and depressed glucose) was observed in 55.6% and 36.1% of patients with TBM and CM, respectively (P=0.002). The in-hospital case-fatality rate were similar between the groups (TBM 29% v. CM 29%, P=0.578).

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical and laboratory characteristics among 206 HIV-infected patients with tuberculous or cryptococcal meningitis.

| Characteristics | Tuberculous meningitis, n(%)(n=108) |

Cryptococcal meningitis, n%(n=98) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographical data | |||

| Age (years) †, median(IQR) | 36 (30–42) | 38.5 (34–43) | 0.008 |

| Male sex (%) | 78 (72.2) | 76 (77.6) | 0.520 |

| CD4 (T cells/μL)†, median(IQR) n=183 | 65 (30–122) | 36 (17–87) | 0.003 |

| CD4 ≥ 50 cells/μL (%) | 60 (61.2) | 30 (35.3) | 0.001 |

| Prior HAART use (%) | 36 (51.0) | 46 (46.9) | 0.643 |

| Prior HIV diagnosis (%) | 63 (61.2) | 95 (96.9) | <0.0001 |

| Clinical data | |||

| Fever (%) | 84 (77.8) | 53 (54.1) | 0.001 |

| Headache (%) | 82 (75.9) | 87 (88.8) | 0.006 |

| Meningeal signs (%) | 20 (19) | 11 (11.8) | 0.241 |

| Seizures (%) | 12 (11.1) | 16 (16.3) | 0.309 |

| Nausea and vomiting (%) | 41 (38.0) | 54 (55.1) | 0.011 |

| Glasgow Coma Scale <15 (%) | 68 (63.0) | 26 (26.5) | <0.0001 |

| Extra-CNS disease (%) | 52 (48.2) | 50 (51.0) | 0.572 |

| Images and laboratorial data | |||

| Ventricular dilatation on cranial CT (%) | 25 (24.8) | 9 (10.8) | 0.021 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL), median(IQR) | 10.7 (9.4–12) | 11.9 (11–13.3) | 0.004 |

| CSF characteristics | |||

| Leukocyte (cells/μL) †, median(IQR) | 160 (16–333) | 6 (2–64) | <0.0001 |

| Lymphocyte predominance (%) | 50/89 (56.2) | 48/49 (98.2) | <0.0001 |

| Neutrophil predominance (%) | 39/89 (43.8) | 1/49 (1.8) | <0.0001 |

| CSF glucose (mmol/l) †, n=205, median(IQR) |

1.6 (1.1–2.7) | 2.1 (1.3–2.7) | 0.142 |

| CSF:blood glucose ratio†, n=183, median(IQR) |

0.3 (0.2–0.5) | 0.3 (0.2–0.5) | 0.601 |

| CSF protein g/l†, n=205 median(IQR) |

0.2 (0.08–2.9) | 0.07 (0.05–1.4) | <0.0001 |

| CSF pleocytosis (%) | 89 (82.4) | 49 (50.0) | <0.0001 |

| CSF glucose < 2.22 mmol/l (%) | 68 (63.0) | 51 (52.0) | 0.157 |

| CSF protein ≥ 0.45g/l (%) | 97 (90.0) | 80 (81.6) | 0.185 |

| CSF Protein ≥ 1.0g/l (%) | 77 (71.3) | 34 (35.1) | <0.0001 |

| Normal CSF# (%) | 5 (4.6) | 13 (13.4) | 0.049 |

| One CSF abnormal parameter (%) | 12 (11.1) | 23 (23.7) | 0.027 |

| Two CSF abnormal parameters (%) | 31 (28.7) | 26 (26.8) | 0.641 |

| Three CSF abnormal parameters (%) | 60 (55.6) | 35 (36.1) | 0.002 |

| Prognosis | |||

| In-hospital case fatality rate (%) | 31 (28.97) | 28 (28.87) | 0.578 |

Notes: values in bold means statistically-significant ones;

median and interquartile range (IQR).

CNS: central nervous system; pleocytosis as ≥5 leukocytes/μL. CSF: cerebrospinal fluid, CT: computed tomography;

CSF parameters: ≥5 leukocytes/μL. glucose <2.22mmol/l and protein ≥0.45g/l.

Microscopy was of limited value. Among TBM patients, Ziehl-Nielsen stain of CSF showed fast-acid bacilli (AFB) in only 5.5% (6/108) of cases. Among cryptococcal patients, India ink staining of CSF showed yeast compatible with Cryptococcus spp. in 84% (82/98) of cases. A cryptococcal antigen latex agglutination test of CSF was positive in only 82% (80/98) of cases.

Tables 2 and 3 show the results of univariate and multivariate modelling to identify variables associated with TBM.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of associated variables with tuberculous meningitis among 206 HIV-infected patients with tuberculous or cryptococcal meningitis.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Male gender | 0.81 (0.43–1.52) | 0.520 | ||

| Age < 40 years | 2.22 (1.24–2.96) | 0.009 | ||

| CD4 T count ≥ 50 cells/μL | 2.90 (1.59–5.28) | 0.001 | ||

| Previous diagnosis of HIV | 0.05 (0.02–0.16) | <0.0001 | ||

| Glasgow Coma Scale < 15* | 4.50 (2.48–8.19) | <0.0001 | 3.10 (1.03–9.34) | 0.044 |

| Fever | 2.84 (1.55–5.19) | 0.001 | ||

| Headache | 0.33 (0.15–0.73) | 0.006 | ||

| Triad of meningism, fever, and headache | 2.49 (0.96–6.46) | 0.072 | ||

| Nausea and vomiting | 0.48 (0.27–0.83) | 0.011 | 0.27 (0.08–0.90) | 0.033 |

| Hemoglobin < 10 g/dl | 2.92 (1.53–5.57) | 0.001 | ||

| CSF pleocytosis** | 4.68 (2.49–8.79) | <0.0001 | 9.43 (1.30–68.7) | 0.027 |

| CSF neutrophil predominance | 32.9 (5.6–195.4) | <0.0001 | 35.81 (3.8–341.3) | 0.002 |

| CSF protein ≥ 1.0g/l | 4.60 (2.56–8.28) | <0.0001 | 5.13 (1.38–19.04) | 0.032 |

| Normal CSF protein, glucose, and leukocytes | 0.31 (0.11–0.88) | 0.049 | ||

| Abnormal CSF protein, glucose, and leukocytes | 2.21 (1.27–3.88) | 0.008 | ||

| Ventricular dilatation on cranial CT | 2.71 (1.20–6.08) | 0.021 | ||

| Brain atrophy on cranial CT | 0.35 (0.15–0.78) | 0.015 | ||

Notes: OR: odds ratio, 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

At admission.

Pleocytosis defined as ≥5 leukocytes/μL.

Adjusted odds ratio was measured by binary logistic regression model (Wald test) included baseline fever, headache, T cell CD4 count, CSF protein, Glasgow Coma Scale at admission, nausea and vomits, pleocytosis, and CSF neutrophil pleocytosis.

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression model to identify associated variables with tuberculous meningitis among 206 HIV-infected patients with tuberculous or cryptococcal meningitis.

| Variable | β | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSF protein ≥ 1.0g/l | 1.635 | 5.13 (1.38–19.04) | 0.014 |

| Glasgow Coma Scale<15* | 1.132 | 3.10 (1.03–9.34) | 0.044 |

| Nausea and vomiting | −1.296 | 0.27 (0.08–0.90) | 0.033 |

| Neutrophil pleocytosis‡ | 3.578 | 35.8 (3.8–341.3) | 0.002 |

| CSF pleocytosis** | 2.244 | 9.43 (1.30–68.7) | 0.027 |

| Constant | −4.252 |

Note: CSF: cerebrospinal fluid.

Pleocytosis was leukocyte>5 cells/μL

At admission,

Neutrophil pleocytosis represent > 50% of CSF leukocytes.

A diagnostic index was derived by the multivariate model: 1.635 x (protein >1.0g/l) + 1.132 x (GCS<15) - 1.296 x (nausea and vomit) + 3.578 x (CSF with polymorphs predominance) + 2.244 x (pleocytosis).

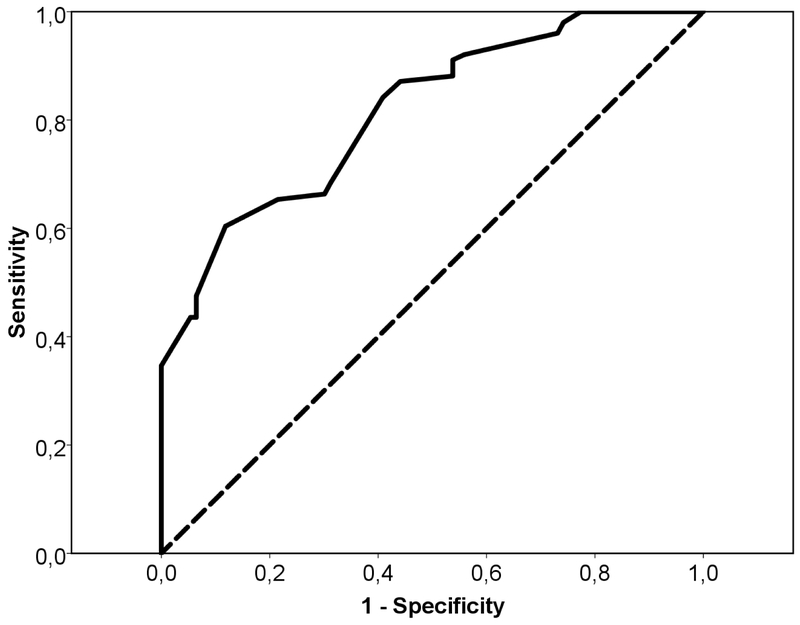

The parameters in parenthesis were coded 1 if present or 0 if absent. We excluded the value of constant in the calculation of index. The diagnostic index was a number that varied from −1.296 to 8.589 and negative values favoured a diagnosis of CM, while positive values favoured a diagnosis of TBM. The area under the ROC curve was 0.815 (95% CI: 0.758–0.873), P<0.0001. At a cutoff of 1.04, sensitivity was 96.0% and specificity, 73.1%. Values > 1.04 presented a remarkable fall in the value of sensitivity - a cutoff of 5.33 presented a specificity of 100%, but a sensitivity of 34.7% - while values < 1.04 values, such −0.73, presented higher sensitivity (100%) but lower specificity (3.2%). Figure 1 shows the ROC curve of the logistic model.

Figure 1.

Logistic regression model ROC curve for HIV-infected patients with tuberculous or cryptococcal meningitis. Area under the curve was 0.815 (95% CI: 0.758–0.873), P<0.0001. At a cut-off of 1.04, sensitivity was 96% and specificity, 73.1%.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge this is the largest study comparing culture-proven CM and TBM in HIV-infected patients. Although some clinical and CSF characteristics appear useful to the discriminate these two diseases, a diagnostic index could not be derived because lack of sensitivity and specificity, similarly to that reported in a previous study,[6] which derived an area under the ROC curve very close to ours in spite of the smaller number of patients in the groups. A highly accurate logistic model did not result in an index with a cut-off sufficiently sensitive and specific to distinguish TBM and CM using clinical and laboratory features.

In the current study, CSF protein >1.0g/l, GCS <15, absence of nausea and vomiting, neutrophil pleocytosis and CSF pleocytosis were independently associated with TBM diagnosis. There are few studies with a heterogeneous design comparing TBM and CM. Similar to our findings, GCS < 15,[6] pleocytosis,[6] neutrophil pleocytosis,[9] have been found related to TBM. Fever,[6,10] neck stiffness,[6] brain CT abnormalities,[10,11] and extrameningeal disease[10] have been reported more frequently in TBM in other studies than in our study. In these studies, the variables of headache,[11] vomiting,[11] altered sensorium,[11] high opening pressure,[6] low CSF white blood cell count,[6] and advanced immunosupression,[9,11] were more frequent in patients with CM. These results indicate that some clinical and laboratory characteristics seem to be useful in the differential diagnosis of TBM and CM, however, in clinical practice, they do not usually allow for sufficient discrimination between these two diseases.

Culture is the mainstay for diagnosis of TBM and CM, but alternative tests are evolving to provide more rapid and reliable diagnosis. In clinical practice, the India ink microscopy stain is usually available for cryptococcal diagnosis in resource-limited settings. Yet, in referral centers in Africa, India ink has only ~85% sensitivity,[12] similar to the sensitivity in our study. India ink can be particularly problematic for early and/or low burden infections, with sensitivity only 40% for quantitative cultures < 1000 colony-forming U/mL of CSF.[12] Thus, cryptococcal antigen (CrAg) tests could be necessary in at least 15% of patients with CM and negative India ink microscopy. In people with AIDS who have a negative India ink microscopy, the most common cause of meningitis is Cryptococcus in high burden regions.[12] Recently, the World Health Organization included the CSF latex CrAg agglutination or lateral flow immunochromatographic assay (LFA) as the preferred diagnostic approach of cryptococcal meningitis.

In our study, the sensitivity of CSF CrAg latex agglutination was only 82%, lower than usually reported for this test (93–100%).[13] CSF CrAg LFA (Immuno-Mycologics, USA) has a reported sensitivity 99.3%, specificity 99.1%, positive predictive value of 99.5% and negative predictive value 98.7%.[12] CrAg LFA is a “dipstick” test that requires only a drop of CSF and is relatively inexpensive, quick and easy to interpret. Unlike traditional latex agglutination, CrAg LFA does not require laboratory infrastructure or cold-chain transport.[13]

Unfortunately, rapid diagnosis of TBM is more complicated. Detection of AFB in patient samples using Ziehl–Neelsen staining is widely employed for diagnosis of TBM. AFB microscopy is, however, insensitive in TBM, with sensitivity rates of about 10–20%.[14] The sensitivity of AFB microscopy in our study was only 5%. The sensitivity of smear microscopy in TBM can be maximized by examination of large-volume CSF samples (>6 ml), using several CSF specimens collected over a few days and prolonged slide examination (≥30 min).[15] However, these criteria are rarely achieved in practice. Recently, some modifications of the Ziehl-Neelsen stain showed optimistic results,[16] but replication in other sites is required. Over several decades, nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis have been evaluated for the diagnosis of TBM. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of commercial NAATs with a CSF of M. tuberculosis culture-positive gold standard found a sensitivity of 64% and a specificity of 98%.[17] Despite suboptimal sensitivity, the rapid turnaround time of NAATs compared with culture enhances its role in the early accurate diagnosis of TBM. However, NAATs are unavailable for most resource-limited laboratories. Yet, the availability of automated NAATs via the GeneXpert system (Cepheid, USA) is increasing, but testing a large volume of centrifuged CSF remains essential.

In terms of the current status of meningitis diagnosis in HIV-infected patients, we would recommend a cryptococcal antigen assay (ideally LFA) as an initial approach of HIV-infected patients with meningitis.[18] Following a negative test in an adequate clinical and CSF context, empiric treatment for TBM should strongly be considered. However, it is important to consider bacteria (e.g. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitides, Listeria monocytogenes) and syphilitic meningitis in the differential diagnosis of meningitis in HIV-infected patients. More-rare aetiologies include other fungal pathogens (i.e Histoplasma capsulatum, Candida, Coccidiodes) and viruses (i.e herpes virus, enterovirus).[19,20]

This study has limitations. We did not have CSF opening pressure available for the whole population. We have included only culture-proven cases, but not culture-negative cases, tested with techniques such as NAAT. Therefore, we did not compare clinical and laboratory differences between culture-positive and culture-negative cases. However, in this study, we include a reasonable number of cases, all of which were culture-proven, allowing rigorous definition of cases.

In conclusion, although some clinical and basic CSF characteristics appear useful in the differential diagnosis of TBM and CM in HIV-infected patients, an accurate algorithm was not identified. In this scenario, optimised access to more rapid, sensitive and specific laboratory tests is essential.

References

- 1.Bergemann A, Karstaedt AS. The spectrum of meningitis in a population with high prevalence of HIV disease. QJM. 1996;89:499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hakim JG, Gangaidzo IT, Heyderman RS, Mielke J, Mushangi E, Taziwa A, et al. Impact of HIV infection on meningitis in Harare, Zimbabwe: a prospective study of 406 predominantly adult patients. AIDS. 2000;14:1401–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Békondi C, Bernede C, Passone N, Minssart P, Kamalo C, Mbolidi D, et al. Primary and opportunistic pathogens associated with meningitis in adults in Bangui, Central African Republic, in relation to human immunodeficiency virus serostatus. Int J Infect Dis. 2006;10:387–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganiem AR, Parwati I, Wisaksana R, van der Zanden A, van de Beek D, Sturm P, et al. The effect of HIV infection on adult meningitis in Indonesia: a prospective cohort study. AIDS. 2009;23:2309–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jarvis JN, Meintjes G, Williams A, Brown Y, Crede T, Harrison TS. Adult meningitis in a setting of high HIV and TB prevalence: findings from 4961 suspected cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;15;10:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen DB, Zijlstra EE, Mukaka M, Reiss M, Kamphambale S, Scholing M, et al. Diagnosis of cryptococcal and tuberculous meningitis in a resource-limited African setting. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15:910–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marais S, Thwaites G, Schoeman JF, Török ME, Misra UK, Prasad K, et al. Tuberculous meningitis: a uniform case definition for use in clinical research. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:803–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trachtenberg JD, Kambugu AD, McKellar M, Semitala F, Mayanja-Kizza H, Samore MH, et al. The medical management of central nervous system infections in Uganda and the potential impact of an algorithm-based approach to improve outcomes. Int J Infect Dis. 2007;11:524–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sánchez-Portocarrero J, Pérez-Cecilia E, Jiménez-Escrig A, Martin-Rabadán P, Roca V, Ruiz Yague M, et al. Tuberculous meningitis. Clinical characteristics and comparison with cryptococcal meningitis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:671–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lan SH, Chang WN, Lu CH, Lui CC, Chang HW. Cerebral infarction in chronic meningitis: a comparison of tuberculous meningitis and cryptococcal meningitis. QJM. 2001;94:247–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Satishchandra P, Nalini A, Gourie-Devi M, Khanna N, Santosh V, Ravi V, et al. Profile of neurologic disorders associated with HIV/AIDS from Bangalore, south India (1989–96). Indian J Med Res. 2000;111:14–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boulware DR, Rolfes MA, Rajasingham R von Hohenberg M, Qin Z, Taseera K, et al. Multisite validation of cryptococcal antigen lateral flow assay and quantification by laser thermal contrast. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makadzange AT, McHugh G. New approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of cryptococcal meningitis. Semin Neurol. 2014;34:47–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thwaites G, Chau TTH, Mai NTH, Drobniewski F, McAdam K & Farrar J. Tuberculous meningitis. Journal Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68: 289–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thwaites GE, Chau TTH, Farrar J. Improving the bacteriological diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. J Clin Microbiol 2004;42:378–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen P, Shi M, Feng GD, Liu JY, Wang BJ, Shi XD, et al. A highly efficient Ziehl–Neelsen stain: identifying de novo intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis and improving detection of extracellular M. tuberculosis in cerebrospinal fluid. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:1166–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Solomons RS, van Elsland SL, Visser DH, Hoek KGP, Marais BJ, Schoeman JF, et al. Commercial nucleic acid amplification tests in tuberculous meningitis—a meta-analysis. Diag Microb Infect Dis. 2014;78:398–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bahr NC & Boulware DR. Methods of rapid diagnosis for the etiology of meningitis in adults. Biomark Med. 2014;8:1085–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Veltman JA, Bristow CC, Klausner JD. Meningitis in HIV-positive patients in sub-Saharan Africa: a review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:19184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lorber B. Listeriosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]