Abstract

The generation of large amounts of functional human pluripotent stem cells-derived cardiac progenitors and cardiomyocytes of defined heart field origin is a pre-requisite for cell-based cardiac therapies and disease modeling. We have recently shown that Id genes are both necessary and sufficient to specify first heart field progenitors during vertebrate development. This differentiation protocol leverages these findings and uses Id1 overexpression in combination with Activin A as potent specifying cues to produce first heart field-like (FHF-L) progenitors. Importantly, resulting progenitors efficiently differentiate (~70–90%) into ventricular-like cardiomyocytes. Here we describe a detailed method to 1) generate Id1-overexpressing hPSCs and 2) differentiate scalable quantities of cryopreservable FHF-L progenitors and ventricular-like cardiomyocytes.

Keywords: Developmental Biology, Issue 136, Cardiac disease modeling, stem cell-based therapies, first heart field-like cardiac progenitors, ventricular-like cardiomyocytes, Id1, hPSCs

Introduction

Large scale production of human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs)-derived cardiac progenitors and cardiomyocytes is a pre-requisite for stem cell-based therapies1, disease modeling2,3 and the rapid characterization of novel pathways regulating cardiac differentiation4,5,6 and physiology7,8. Although a number of studies9,10,11,12,13,14,15 have previously described highly efficient cardiac differentiation protocols from hPSCs, none has addressed the heart field origin of resulting cardiomyocytes, in spite of the identification of significant molecular differences between left (first heart field) and right (second heart field) ventricular cardiomyocytes16 and the existence of heart field-specific congenital heart diseases; i.e., hypoplastic left heart syndrome17 or arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia18. Thus, the generation of cardiac progenitors and cardiomyocytes of defined heart field origin from hPSCs is becoming a necessity in order to increase their relevance as therapeutic and disease modeling tools.

This protocol relies on the constitutive overexpression of Id1, a recently identified5 first heart field-specifying cue that in combination with Activin A, is both necessary and sufficient to initiate cardiogenesis in hPSCs. Notably, Cunningham et al. (2017)5 show that Id1-induced progenitors specifically express first heart field (HCN4, TBX5) but not second heart field markers (SIX2, ISL1) as they undergo cardiac differentiation. In addition, the authors also show that transgenic mouse embryos lacking the entire Id family of genes (Id1-4), develop without forming first heart field cardiac progenitors, while more medial and posterior cardiac progenitors (second heart field) can still form, thereby suggesting that Id proteins are essential to initiate first heart field cardiogenesis in vivo. Conveniently, Id1-induced progenitors can be cryopreserved and spontaneously differentiate into cardiomyocytes displaying ventricular-like characteristics, including ventricular-specific markers (IRX4, MYL2) expression and ventricular-like action potentials.

Here we describe a simple and scalable method to generate first heart field-like (FHF-L) cardiac progenitors and ventricular-like cardiomyocytes from Id1 overexpressing hPSCs. An important feature of this protocol is the possibility to uncouple cardiac progenitor generation from subsequent cardiomyocyte production using a convenient cryopreservation step. In summary, this protocol details the necessary steps to (1) generate Id1-overexpressing hPSCs, (2) generate FHF-L cardiac progenitors from hPSCs, (3) cryopreserve resulting progenitors, and (4) resume FHF-L cardiac progenitor differentiation and generate highly enriched (>70–90%) beating ventricular-like cardiomyocytes.

Protocol

1. Id1 Virus Preparation and Infection

Generate Id1 overexpressing lentivirus by co-transfecting pCMVDR8.74, pMD2.G, and pCDH-EF1-Id1-PGK-PuroR (Addgene: plasmid #107735) into HEK293T cells. Collect viral particles, filtrate, purify from the supernatant, and store at -80 °C as in Kitamura et al. (2003)19. Alternatively, produce Id1 lentivirus commercially by sending pCDH-EF1-Id1-PGK-PuroR to a lentivirus-producing vendor. Caution: Please follow lentiviral safety regulations and standard operation protocols. Note: IMPORTANT: Optimal virus titer should be at least 108 to 109 Transducing Units/mL (TU/mL).

Prior to infection, coat one well of a 96 well plate with 50 µl of coating reagent, typically a gelatinous protein mixture secreted by Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm mouse sarcoma cells (see Table of Materials).

Dissociate one well of pluripotent stem cells grown in a 6 well plate by adding 1 mL of PBS without Ca2+ and Mg2+ and with 0.5 mM EDTA. NOTE: Dissociation time varies from 3–10 min. When more than 80% of the cells are detached from the bottom of the plate, proceed to next step.

Collect cell suspension with sterile pipet into 15 mL plastic centrifuge tube.

Neutralize dissociation reagent with 5 mL of PBS-containing Ca2+ and Mg2+.

Pellet cells by centrifugation (200 x g for 3 min).

Remove supernatant and gently flick the tube in order to dislodge the pellet.

Re-suspend cells in 1 mL of stem cell media.

Count cells using an automated cell counter following vendor instructions.

Plate 20,000 viable cells per coated well (96-well plate) in 50 µL of stem cell media supplemented with 2 µM RHO/ROCK pathway inhibitor (see Tables 1 and 2).

After 24 h, monitor for cell attachment and replace media with 100 µl stem cell media supplemented with 2 µM RHO/ROCK pathway inhibitor and 6 ng/mL hexadimethrine bromide (see Tables 1 and 2), one h prior to lentiviral infection. NOTE: Cells should be firmly attached to the bottom of the plate.

Thaw Id1-lentivirus on ice.

Add 3 µL of purified lentivirus per well (virus titer should be between 108 to 109 TU/mL), and then transfer the plate back to cell culture incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2, 20% O2).

24 h post-viral infection, add 100 µL of fresh stem cell media to infected cells.

48 h post-lentiviral infection, replace virus containing media with 200 µL of fresh stem cell media supplemented with 1 µg/mL puromycin.

Refresh media daily with 200 µL of stem cell media supplemented with 1 µg/mL puromycin.

When cultures reach 80% confluency, dissociate cells using 200 µL of PBS without Ca2+ and Mg2+ + 0.5 mM EDTA (for one well of a 96-well plate).

Collect cell suspension into a centrifuge tube.

Neutralize dissociation reagent with 5 mL of PBS-containing Ca2+ and Mg2+.

Pellet cells by centrifugation (200 x g for 3 min).

Remove supernatant and gently flick the tube in order to dislodge the pellet.

Re-suspend cells in 1 mL of stem cell media supplemented with 2 µM RHO/ROCK pathway inhibitor.

Transfer all cells (1 mL) to a coated well of a 12-well plate.

After 24 h, monitor for cell attachment to the well and replace media with 1 mL of stem cell media supplemented with 2 µM RHO/ROCK pathway inhibitor and 6 ng/mL hexadimethrine bromide, one h prior to transduction.

Thaw Id1-lentivirus on ice.

Add 5 µL of purified virus per well (12-well plate).

24 h post-lentiviral infection, replace virus containing media with 1 mL of fresh stem cell media supplemented with 3 µg/mL puromycin.

48 h post lentiviral infection, replace virus containing media with 1 mL of fresh stem cell media supplemented with 6 µg/mL puromycin.

When cultures reach 80% confluency, dissociate cells using 500 µL of PBS without Ca2+ and Mg2+ and with 0.5 mM EDTA (for one well of a 12-well plate).

Transfer half (250 µL) of the cell suspension to one well of a coating reagent coated 6-well plate containing 2 mL of stem cell media supplemented with 2 µM RHO/ROCK pathway inhibitor.

Use the other half (250 µL) of the sample for RNA extraction and qRT-PCR in order to determine lentiviral-mediated Id1 expression levels, as in Colas et al. (2012)4. NOTE: IMPORTANT: If Id1 mRNA expression levels are lower than 0.005 fold of GAPDH expression levels (see Table 3 for qRT-PCR primers), repeat infection process as described above until Id1 expression levels exceed the threshold.

2. hPSCsId1 Maintenance

Culture hPSCsId1 in coated 6 well-plates and grow in 3 mL per well of stem cell media supplemented with 6 µg/mL puromycin.

When hPSCsId1 reach 80% confluency, passage cells as aggregates (1:6 split ratio) using enzyme-free dissociation reagent following vendor guidelines and grow in 3 mL per well of stem cell media supplemented with 6 µg/mL puromycin.

3. Preparation of hPSCsId1 for Differentiation

Coat a 12-well plate with 500 µL per well of coating reagent.

When hPSCsId1 reach 90% confluency dissociate cells by adding 1 mL of PBS without Ca2+ and Mg2+ and with 0.5 mM EDTA per well for 5–10 min. Check dissociation process every minute, and once 80% of the cells are dissociated from the plate, proceed to the next step.

Collect cell suspension into a centrifuge tube.

Neutralize dissociation reagent with 5 mL of PBS-containing Ca2+ and Mg2+.

Pellet cells by centrifugation (200 x g for 3 min).

Remove supernatant and gently flick the tube in order to dislodge the pellet.

Re-suspend cells in 2 mL of stem cell media supplemented with 2 µM RHO/ROCK pathway inhibitor.

Count cells using an automated cell counter.

Plate 300,000 cells per well in 1 mL of stem cell media supplemented with 2 µM RHO/ROCK pathway inhibitor and 6 µg/mL puromycin, and transfer plate into tissue culture incubator.

Refresh media daily with 2 mL of stem cell media supplemented with 6 µg/mL puromycin until cultures reach 90% confluency. At this point, initiate cardiac differentiation (next step).

4. Differentiation of hPSCsId1 into First Heart Field-like Cardiac Progenitors (FHF-L CPs)

For 12-well plate format, initiate differentiation (day 0) by replacing stem cell media with 1.5 mL of induction media (Table 1) supplemented with Activin A (100 ng/mL) (see Table 2 for recommended volumes and Activin A concentrations for different plate formats).

On day 1 (24 h after differentiation is initiated), replace media with 2 mL of induction media without Activin A (per well of a 12-well plate).

On day 3, replace media with 2 mL of induction media without Activin A (per well of a 12-well plate).

On day 5, collect FHF-L CPs for cryopreservation (next step). NOTE: IMPORTANT: Cryopreservation is preferred at this point, as it enables to uncouple cardiac progenitor generation from subsequent cardiomyocyte production and biobank large batches of cells. Note that alternatively, day 5 FHF-L CPs can be passed to a freshly coated plate to continue differentiation, please refer to Steps 5.1–5.5 to passFHF-L CPs and then proceed to Step 6.5 for differentiation.

5. Cryopreservation of FHF-L CPs

Aspirate all media from wells containing day 5 FHF-L CPs and quickly add 1 mL of warm (37 °C) 1x enzyme-containing dissociation reagent (see Table of Materials). Place plate in the tissue culture incubator.

After 1 min, shake plate side to side in the incubator.

After 2 min (total time), remove plate from the incubator and add 1 mL of 10% FBS media.

Gently pipet cells up and down with a 5 mL pipet to facilitate cell detachment from the plate.

Collect cell suspension to a centrifuge tube and pellet cells by centrifugation at 200 x g for 3 min

Re-suspend cell pellet in 2 mL of cryopreservation reagent.

Count cells using an automated cell counter.

Add cryopreservation reagent (see Table of Materials) at a sufficient volume to cryopreserve cells at desired concentration (typically 5–10 x 106 cells/mL).

Transfer cells to cryopreservation vials and place vials in cooling device (1 °C/min) and place cooling device in -80 °C freezer overnight.

After 24 h, transfer frozen vials to liquid nitrogen for long term storage. NOTE: The protocol can be paused here.

6. FHF-L CP Differentiation Into Ventricular-like Cardiomyocytes

Transfer day 5 FHF-L CPs frozen vials from liquid nitrogen storage into dry ice container.

Place vials in 37 °C water bath for 2 to 3 min, until cell suspension is thawed completely. NOTE: IMPORTANT: The thawing process is time-sensitive. Exposing cells to the cryopreservation media for an excessive amount of time (i.e., 10 min) will decrease cell viability.

Transfer cells to 15 or 50 mL centrifuge tube, depending on the number of thawed vials.

Dispense dropwise (5 drops every 30 seconds) pre-warmed (37 °C) cardiogenic media (Table 1) to cell solution. Continue this process until a 1:3 cryopreservation media:cardiogenic media ratio is reached. At this point, increase the cardiogenic media addition rate until a 1:10 cryopreservation media:cardiogenic media ratio is reached. NOTE: IMPORTANT: Rapid osmolarity changes will increase cell death during the thawing process; therefore, dropwise addition of cardiogenic media as described above is highly recommended.

Centrifuge cell suspension and pellet cells by centrifugation (200 x g for 3 min).

Remove supernatant and gently flick centrifuge tube to dislodge cell pellet.

Re-suspend cells with cardiogenic media supplemented with 2 µM RHO/ROCK pathway inhibitor. Note: Cell viability can vary from thaw to thaw, and, in general, > 65% viability predicts good plating efficiency.

Dilute concentrated cell suspension with cardiogenic media supplemented with 2 µM RHO/ROCK pathway inhibitor to obtain the desired cell concentration for plating (see Table 2 for different plate formats). NOTE: IMPORTANT: Note that cardiac differentiation efficiency may decline if cells are seeded too sparsely.

Seed cells on plate.

Keep plate in the tissue culture hood for 20 min before transferring it to tissue culture incubator.

On day 6 of differentiation, monitor cell attachment. NOTE: Cardiac progenitors are cryopreserved on day 5 of the differentiation. 24 h after thawing the cells would be on day 6 of the differentiation. NOTE: The presence of floating (dead) cells is common.

On day 7, aspirate 50% of the media and replace with an equal amount of fresh cardiogenic media. NOTE: The addition of RHO/ROCK pathway inhibitor to the cardiogenic media is not necessary after this point.

Replace 50% of the media with cardiogenic media every other day.

Note spontaneous beating that appears between day 11 and day 13.

On day 15, quantify cardiac differentiation efficiency by immunofluorescence using DAPI (nucleus stain) and ACTC1 (pan-cardiac marker).

7. Passing and Maintenance of Ventricular-like Cardiomyocytes

NOTE: By day 14–16, a monolayer of spontaneously contracting ventricular-like cardiomyocytes should be obtained. At this point, it is suggested to dissociate and re-plate cardiomyocytes in order to homogenize the culture and prevent cells from detaching from the plate.

Aspirate all media from wells and quickly add 1 mL of pre-warmed (37 °C) 1x enzyme-containing dissociation reagent. NOTE: 1x enzyme-containing dissociation reagent volumes vary depending on plate format, but should completely cover the bottom of the well surface.

Transfer plate into a tissue culture incubator.

Gently shake plate side to side every 2 min inside the incubator to accelerate the detachment process.

After 5–15 min, when 80% to 100% of the cells are detached from the bottom of the plate, remove the plate from the incubator and inhibit 1x enzyme-containing dissociation reagent activity by adding an equal volume of 10% FBS media. NOTE: Incubation time with 1x enzyme-containing dissociation for this process will vary from batch-to-batch.

Collect cell suspension to a centrifuge tube.

Mix cell suspension with pipet and count cells using an automated cell counter.

Dilute cell suspension to desired cell concentration (see Table 2 for different plate formats) with maintenance media supplemented with 2 µM RHO/ROCK pathway inhibitor.

After seeding cardiomyocytes onto the plate, distribute the cells evenly and allow the cells to attach for 10–20 min before transferring plate to tissue culture incubator.

24 h after re-plating, monitor cell attachment and recovery. NOTE: The presence of floating (dead) cells is common. 48–72 h after re-plating, cardiomyocyte should resume spontaneous contraction.

To maintain cardiomyocyte culture, replace 50% of the media with the maintenance media every other day until use of ventricular-like cardiomyocytes for subsequent experiments.

Representative Results

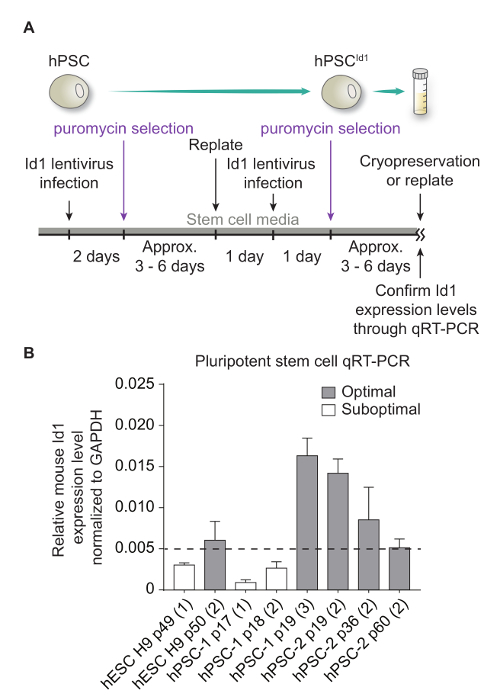

Generation of hPSCsId1lines hPSCs are infected with a lentivirus mediating Id1 overexpression (Figure 1A). Once hPSCId1 are generated, transgene expression is quantified by qRT-PCR (Figure 1B). Only hPSCId1 lines expressing Id1 mRNA at levels greater than 0.005 fold of that of GAPDH should be used for differentiation.

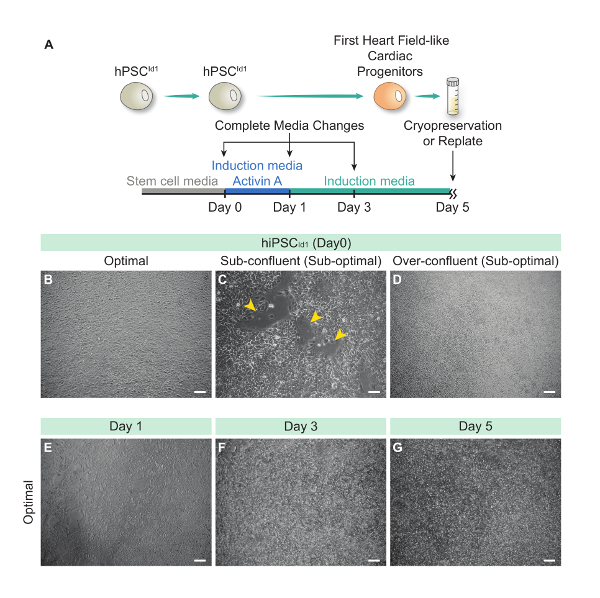

hPSCsId1 Maintenance and Preparation for Differentiation Optimal culture conditions are necessary and critical for successful first heart field-like cardiac progenitor differentiation (Figure 2A). hPSCId1 cultures should be monitored daily for stem morphology maintenance and continuous proliferation. Differentiation should be initiated when tightly packed stem cell colonies reach >90% confluency (Figure 2B). If differentiation is initiated prior to optimal confluency, cell death is enhanced and differentiation efficiency may decline (Figure 2C). Similarly, overgrown cultures will perform poorly (Figure 2D).

Generation of First Heart Field-Like Cardiac Progenitors (FHF-L CPs) From hPSCsId1 On day 1 (24 h post differentiation initiation), cells should be monitored to observe loss of stem morphology (cells appear flatter and darker than stem cells). Note that cell death is common during the first day of differentiation, but cell confluence should be maintained at >75% (Figure 2E). If after 24 h of differentiation, 50% or more of the covered surface area is lost, cells should be discarded.

On day 3, differentiating cells should remain clustered and have filled gaps created during the initial 24 h time period (Figure 2F). Flat cells growing independently are indicative of suboptimal differentiation conditions.

On day 4, optimal differentiation should show continued expansion and coverage of the plate.

On day 5, cells are harvested and cryopreserved. Optimal differentiations should result in tightly connected cell clusters with homogeneous morphology appearance (Figure 2G). Note that low density clusters of flat cells mark a suboptimal differentiation outcome. See Table 2 for the average yield of day 5 cardiac progenitors per well in various culture formats.

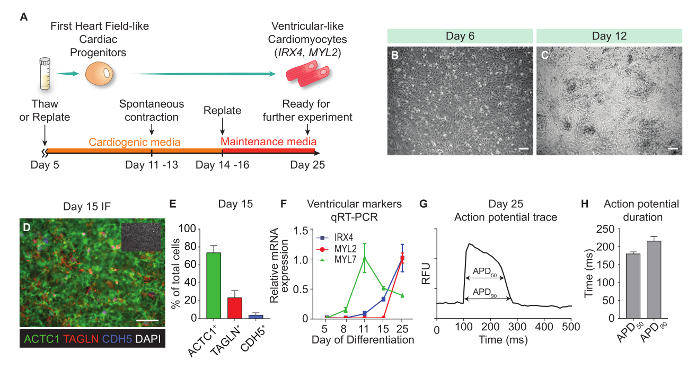

Generation of Ventricular-like Cardiomyocytes From FHF-L CPs Day 5 FHF-L CPs are thawed at plate format-dependent densities described in Table 2, in order to maximize their cardiac differentiation potential (Figure 3A and Table 2). The viability after thawing needs to be monitored. Generally, viability ranges from 70–80%. If the viability is below 60%, the yield of cardiomyocytes would be affected.

On day 6 (24 h after resuming differentiation), FHF-L CPs should cover >90% of the available surface area and appear as a homogenous single layer of cells (Figure 3B). Low confluence on day 6 will reduce FHF-L CPs differentiation into cardiomyocytes.

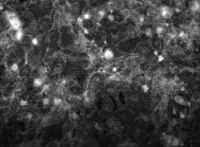

Resulting cardiomyocytes start to beat by day 11–13 of differentiation (Figure 3C and Movie 1). During the day 14–16 replating process, see Table 2 for the average yield of cardiomyocytes per well in various culture formats. Differentiation efficiency is typically assessed by immunofluorescence for cardiac (ACTC1), fibroblast (TAGLN) and vascular endothelial markers (CDH5) and nuclear (DAPI) markers. Lineage quantification is performed using automated imaging and fluorescence quantification, as in Cunningham et al. (2017)5 (Figure 3D-E). Subtype characterization of resulting cardiomyocytes is performed by qRT-PCR (Figure 3F) and action potential transient analysis using kinetic imaging and voltage sensing probes (Figure 3G and Movie 2). Fluorescence quantification for the voltage probe and resulting action potential trace analysis (Figure 3H) is performed as described in McKeithan et al. (2017)7.

Figure 1: Generation of hPSCId1 lines. (A) Schematic representation of the hPSCsId1 generation protocol. (B) Examples of qRT-PCR results showing representative Id1 mRNA levels generated by lentiviral-mediated expression from distinct lines of hPSCId1 including one hESC line and two lines of hPSC lines. Dashed line represents Id1 expression threshold, below which hPSCId1 lines need to undergo an additional cycle of Id1-lentivirus infection. "p" indicates the passage number. The number in the parenthesis indicates the number of rounds of Id1-lentiviral infection. Error bars represent standard deviation of experiments performed in triplicate. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: Generation of First Heart Field-Like Cardiac Progenitors (FHF-L CPs) Differentiation From hPSCId1. (A) Schematic representation of the FHF-L CP generation protocol. Representative bright field pictures of hPSCId1 (day 0) at optimal (B), sub-confluent (yellow arrowheads indicate the void regions between cells) (C) and over-confluent (D) densities. Representative bright-field pictures of differentiating hPSCId1 at day 1, 3 and 5 respectively (E), (F), (G).Scale bar = 100 µm. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3: Generation of Ventricular-like Cardiomyocyte From FHF-L CPs. (A)Schematic representation of the ventricular-like cardiomyocyte generation protocol. (B) Bright field image of day 6 differentiation cells (one day post-thawing). (C) Bright field image of a day 12 beating culture. (D) Representative immunofluorescence image of day 15 cultures (384-well plate format). ACTC1 marks cardiomyocytes, TAGLN: fibroblasts/smooth muscle, CDH5: vascular endothelial cells, and DAPI: nuclei (shown in the inset). (E) Lineage quantification of day 15 cultures. (F) qRT-PCR data time course expression from day 5 to day 25 of ventricular-specific markers (IRX4 and MYL2) and pan-cardiac marker (MYL7). (G) Representative action potential trace from ventricular-like cardiomyocytes at day 25 of differentiation. (H) Action potential duration measurements (APD50 and APD90) of resulting ventricular-like cardiomyocytes (n = 12). Error bars represent standard deviation of experiments performed in quadruplicate (unless otherwise noted). Scale bars = 100 µm. RFU, relative fluorescence unit. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

| Medium | Base medium | Additive |

| Stem Cell Media | mTesR1 | n/a |

| Induction Media | RPMI 1640 Medium | B-27 Serum-Free Supplement without insulin, 1x |

| Induction Media | RPMI 1640 Medium | Puromycin, 6 µg/ml |

| Induction Media | RPMI 1640 Medium | Penicillin-Streptomycin, 1x |

| Cardiogenic Media | RPMI 1640 Medium | B-27 Serum-Free Supplement, 1x |

| Cardiogenic Media | RPMI 1640 Medium | Penicillin-Streptomycin, 1x |

| Maintenance Media | RPMI 1640 Medium | B-27 Serum-Free Supplement, 1x |

| Maintenance Media | RPMI 1640 Medium | KnockOut Serum Replacement, 2% |

| Maintenance Media | RPMI 1640 Medium | Penicillin-Streptomycin, 1x |

Table 1: Media components (see Table of Materials for base media and additives).

| 384 well | 96 well | 12 well | 6 well | 100 mm | 150 mm | |

| Coating volume (per well) | 10 µL | 50 µL | 500 µL | 1 mL | 5 mL | 10 mL |

| Medium volume (per well) | 100 µL | 300 µL | 2 mL | 5 mL | 12 mL | 30 mL |

| Differentiation day 0 activin A concentration (ng/mL) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 300 | ||

| Cardiac progenitor day 5 yield (cells/well) | 1.0 – 1.2 x 105 | 2.5 – 3.0 x 105 | 1.0-1.5 x 107 | 2.0 – 3.0 x 107 | ||

| Cardiac progenitor day 5 replating or thawing density (cells/well) | 2.0 x 104 | 7.5 x 105 | 4.5 x 106 | 8.0 x 106 | 2.2 x 107 | |

| Ventricular-like cardiomyocyte day 14–16 yield (cells/well) | 2.0 – 5.0 x 104 | 0.8 – 1.2 x 106 | 3.5 – 5.0 x 106 | 0.8 – 1.2 x 107 | 1.8 – 2.5 x 107 | |

| Ventricular-like cardiomyocyte replating density (cells/well) | 2.5 x 104 | 1.0 x 106 | 4.5 x 106 | 1.0 x 107 | 2.2 x 107 |

Table 2: Scalable differentiation parameters (coating volume, medium volume, Activin A concentration, yields, replating densities).

| Gene Name | Gene Bank Accession | Sequence |

| GAPDH | NM_001256799 | F: GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT R: GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG |

| mouse Id1 | NM_010495 | F: CCTAGCTGTTCGCTGAAGGC R: CTCCGACAGACCAAGTACCAC |

| IRX4 | NM_016358 | F: GGCTCCCCAGTTCTTGATGG R: TAGACCGGGCAGTAGACCG |

| MYL2 | NM_000432 | F: TTGGGCGAGTGAACGTGAAAA R: CCGAACGTAATCAGCCTTCAG |

| MYL7 | NM_021223 | F: GCCCAACGTGGTTCTTCCAA R: CTCCTCCTCTGGGACACTC |

Table 3: qRT-PCR primer sequences.

Movie 1: Bright field recording (100 frames/s) of day 15 cardiomyocytes where spontaneous contractions can be observed.

Please click here to view this video. (Right-click to download.)

Movie 1: Bright field recording (100 frames/s) of day 15 cardiomyocytes where spontaneous contractions can be observed.

Please click here to view this video. (Right-click to download.)

Movie 2: Kinetic imaging (100 frames/s) of voltage-sensitive fluorescent probe in day 25 id1-induced ventricular-like cardiomyocytes.

Please click here to view this video. (Right-click to download.)

Movie 2: Kinetic imaging (100 frames/s) of voltage-sensitive fluorescent probe in day 25 id1-induced ventricular-like cardiomyocytes.

Please click here to view this video. (Right-click to download.)

Discussion

For successful differentiations, make sure to closely follow instructions listed above. In addition, here we highlight key parameters that strongly influence differentiation outcomes. Before starting a differentiation, the following three morphological parameters should be observed: a stem morphology of hPSCsId1, a high cellular compaction and a high confluence (>90%) of the culture at day 0. In that regard, optimal differentiation conditions are best created by plating dissociated hPSCsId1 as single cells and allowing them to form tightly clustered monolayers that grow to ~90% confluence during the course of 2 to 3 days. Conversely, if hPSCId1 cultures show poor cell and colony morphology, low colony compaction and the presence of large areas of differentiation within the culture, successful FHF-L CP differentiation are unlikely.

Media volume and Activin A concentrations are critical parameters of FHF-L CP differentiation and plate format-dependent (see Table 2). Also note that optimal Activin A concentrations may vary depending on used hPSC line and may require concentration optimization.

Id1 mRNA levels in hPSCs are crucial to efficiently promote FHF-L CP. Suboptimal Id1 levels will fail to produce robust FHF-L CP differentiation and massive cell death by day 1 of differentiation will be observed. The relative expression ratio of Id1-to-GAPDH must exceed 0.005 to promote efficient differentiation. Continued selection using higher doses of puromycin (6–10 µg/mL) is recommended in order to retain high levels of lentiviral-mediated Id1 expression. An evaluation of Id1 mRNA levels every 10 passages is recommended.

Plating densities of day 5 FHF-L CPsis also a critical parameter for cardiac differentiation efficiency. If day 5 FHF-L CPs are plated at low densities, the relative cardiac yield will decrease. Optimal plating densities are listed in Table 2 and are plate format-dependent.

The main limitation for this protocol is the use of lentiviral-mediated Id1 overexpression to promoteFHF-L CP differentiation which may restrict the therapeutic use of resulting progenitors and ventricular-like cardiomyocytes. Also, since lentiviruses may integrate at sites that could potentially affect hPSC maintenance and/or developmental potential, stemness of hPSCsId1 colonies should be monitored by evaluating stem gene expression and observing morphological signs of differentiation. Note that overexpressing Id1 using non-integrative vectors would overcome this limitation and is currently being investigated in our laboratory.

One convenient feature of this method is the simplicity of the differentiation protocol as it only requires one cytokine, Activin A, to generate FHF-L CPs from hPSCsId1. In comparison, other protocols 9,10,11,12,13,14,15 require complex sequences of combinations of cytokines and/or small molecules in order to promote and maintain cardiac differentiation. In addition, this protocol uniquely describes a convenient cryopreservation step which enables to uncouple FHF-L CP generation from subsequent cardiomyocyte production. This feature enables to biobank large batches of FHF-L CPs and to quickly generate cardiomyocytes from frozen progenitors, as cardiac differentiation resumes from day 5 upon thawing. This strategy allows to gain 1 to 2 weeks of time as compared to starting cardiac differentiation from hPSCs. In addition, and most importantly, this protocol is the first protocol to date to generate cardiac progenitors of defined heart field origin, while other protocols9,10,11,12,13,14,15 remain undefined in that regard.

In summary, this protocol outlines a robust and scalable method to produce large amounts (>108–109) of developmentally-relevant FHF-L CPs and ventricular-like cardiomyocytes. In turn, resulting cells can be used to identify novel regulatory pathways controlling cardiac differentiation and physiology, and for regenerative and disease modeling purposes.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Colas lab for helpful discussions and critical reviews of the manuscript. This study was supported by NIH/NIEHS R44ES023521-02 and CIRM DISC2-10110 grants to Dr. Colas.

References

- Chong JJ, et al. Human embryonic-stem-cell-derived cardiomyocytes regenerate non-human primate hearts. Nature. 2014;510:273–277. doi: 10.1038/nature13233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodo K, et al. iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes reveal abnormal TGF-beta signalling in left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy. Nature cell biology. 2016;18:1031–1042. doi: 10.1038/ncb3411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C, et al. Studying arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia with patient-specific iPSCs. Nature. 2013;494:105–110. doi: 10.1038/nature11799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colas AR, et al. Whole-genome microRNA screening identifies let-7 and mir-18 as regulators of germ layer formation during early embryogenesis. Genes & development. 2012;26:2567–2579. doi: 10.1101/gad.200758.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham TJ, et al. Id genes are essential for early heart formation. Genes & development. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McKeithan WL, Colas AR, Bushway PJ, Ray S, Mercola M. Serum-free generation of multipotent mesoderm (Kdr+) progenitor cells in mouse embryonic stem cells for functional genomics screening. Current protocols in stem cell biology. 2012. p. 13. Chapter 1, Unit 1F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McKeithan WL, et al. An automated platform for assessment of congenital and drug-induced arrhythmia with hipsc-derived cardiomyocytes. Frontiers in physiology. 2017;8:766. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, et al. High-throughput screening of tyrosine kinase inhibitor cardiotoxicity with human induced pluripotent stem cells. Science translational medicine. 2017;9 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burridge PW, et al. Chemically defined generation of human cardiomyocytes. Nature methods. 2014;11:855–860. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattman SJ, et al. Stage-specific optimization of activin/nodal and BMP signaling promotes cardiac differentiation of mouse and human pluripotent stem cell lines. Cell stem cell. 2011;8:228–240. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laflamme MA, et al. Cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells in pro-survival factors enhance function of infarcted rat hearts. Nature biotechnology. 2007;25:1015–1024. doi: 10.1038/nbt1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian X, et al. Robust cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells via temporal modulation of canonical Wnt signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:1848–1857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200250109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willems E, et al. Small molecule-mediated TGF-beta type II receptor degradation promotes cardiomyogenesis in embryonic stem cells. Cell stem cell. 2012;11:242–252. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, et al. Human cardiovascular progenitor cells develop from a KDR+ embryonic-stem-cell-derived population. Nature. 2008;453:524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature06894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palpant NJ, et al. Generating high-purity cardiac and endothelial derivatives from patterned mesoderm using human pluripotent stem cells. Nature protocols. 2017;12:15–31. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLaughter DM, et al. Single-cell resolution of temporal gene expression during heart development. Developmental cell. 2016;39:480–490. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, et al. The complex genetics of hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Nature genetics. 2017;49:1152–1159. doi: 10.1038/ng.3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrado D, Link MS, Calkins H. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. New England journal of medicine. 2017;376:1489–1490. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1701400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura T, et al. Retrovirus-mediated gene transfer and expression cloning: powerful tools in functional genomics. Experimental hematology. 2003;31:1007–1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]