Abstract

Background

Many healthcare organizations have developed processes for supporting the emotional needs of patients and their families following medical errors or adverse events. However, the clinicians involved in such events may become “second victims” and frequently experience emotional harm that impacts their personal and professional lives. Many “second victims”, particularly physicians, do not receive adequate support by their organizations.

Methods

A multidisciplinary team was assembled to create a Clinician Peer Support Program (PSP) at a large academic medical center including both adult and pediatric hospitals. A curriculum was developed to train clinicians to provide support to their peers based on research of clinician response to adverse events, utilization of various support resources, and clinician resiliency and ways to enhance natural resilience. Between April 2014 and January 2017, 165 individuals were referred to the program including 68 (41.2%) residents, 17 (10.3%) fellows, 70 (42.4%) faculty members, 6 (3.6%) NPs/PAs and 4 (2.4%) CRNAs. An average of 4.8 individuals were referred per month (Range 0-12). Of the 165 clinicians referred, 17 (10.3%) declined follow-up from the program. Individuals receiving support had a median of two interactions (Range 1-10). Among those receiving support from the PSP, 16 (10.8%) required referral to a higher level of support.

Conclusions

We describe the multiple steps necessary to create a successful peer support program focused on physicians and mid-level providers. There is an unmet need to provide support to this group of healthcare providers following medical errors and adverse events.

Keywords: Second Victim, peer support, clinician well-being

Introduction

Since the release of the Institute of Medicine’s groundbreaking report “To Err is Human”, there has been intense focus to improve the safety of healthcare. However, patients continue to experience harm during encounters with healthcare.1, 2,3 One important advancement in the response to medical errors has been to support the emotional needs of patients and families after the event.4, 5

There is significant evidence that healthcare providers also experience emotional harm following errors and adverse events. Despite the development of systems and processes to support patients, many healthcare organizations have ignored the emotional harm healthcare providers experience as a consequence of medical error or adverse events. Healthcare providers involved in such events have often been labeled the “second victims” of medical error.6 These clinicians may feel shame, guilt, depression, and fear.7–11 In addition, these individuals are more likely to have decreased job satisfaction and quality of life and to be at increased risk of burnout.12, 13

In order to provide support to clinicians following medical errors and adverse events, healthcare organizations have often relied on group support or employee assistance programs (EAPs) to provide support to clinicians.14 However, prior studies suggest that EAPs are underutilized by physicians, and that physicians are more willing to seek support from peer groups.15, 16

Disclosure and support for patients following adverse events is a well-established standard at our hospitals; caring for caregivers, especially physicians, is a gap in the broad organizational response to adverse events and errors. This manuscript details the development of a clinician peer support program (PSP) at a large academic medical center that includes both adult and pediatric hospitals. We describe the process used to select and train PSP providers, identify those needing support and barriers to program development.

Methods

Setting

Barnes-Jewish Hospital (BJH), is a 1251 bed tertiary care facility that provides care to adult patients in St. Louis, MO and is affiliated with St. Louis Children’s Hospital (SLCH), a 280 bed pediatric hospital. Both hospitals serve as the primary teaching affiliates of the Washington University School of Medicine (WUSM). Over 2400 physicians including 1350 members of the Washington University Physicians Faculty Practice Plan and 1200 trainees provide care in the inpatient and outpatient settings.

Developing Clinician Peer Support Program

The Washington University School of Medicine Clinician Peer Support Program was launched in April 2014 with the goal of providing trusted, trained peers who could provide support to clinicians (defined as physicians, residents, fellows, physician assistants[PA], nurse practitioners [NP] and certified registered nurse anesthetists [CRNA]) following medical errors and adverse events. The program was developed with the support of the Washington University School of Medicine, WUSM Faculty Practice Plan and respective risk management and General Counsel departments.

Training Development

A primary goal of the PSP was to facilitate the availability of trained clinicians to support clinician peers who have experienced an adverse event or medical error. To accomplish this goal, a core training development team consisting of physician patient safety officers, members of the safety, legal and risk management departments, psychiatrists and education experts was formed. The team developed an educational module through an iterative process based on available research into physician resilience and methods of enhancing resilience. Prospective peer supporters from a variety of specialties and levels of training participated in an initial small group, two-hour, live training session. Three training sessions were held; feedback was obtained from participants during group interviews after each session allowing for modifications of the training program.

The final training program focused on providing evidence-based information on the emotional and functional impact of adverse events and medical errors for involved clinicians, reviewing positive coping mechanisms helpful for clinicians involved in adverse events from research on clinician resiliency, and educating peer supporters on established warning signs, known risk factors for depression and/or suicide, that suggest a clinician may need additional support or care from identified internal or external resources. Since many of the initiating events may go through internal safety or quality evaluations, peer supporters were also educated on the details of these processes. Given the sensitive nature of the potential interactions with individuals requiring support, simulation exercises were used during training sessions to model and practice the initial and subsequent interactions between the peer supporter and recipient. These exercises focused on assisting the supported clinician in recognizing and coping with the emotional impact of an event by enhancing the clinician’s natural resiliency skills in a non-judgmental fashion and helping to identify existing support networks. Peer support trainees participated in simulations in pairs. During these simulations, peer supporters were trained to use active, empathetic listening skills and inquiry to help the individual reflect on their experience. The peer support clinician was trained to help elicit subtle ways that the stressor event may be affecting the clinician including impacting their sleep, hobbies or relationships outside of the hospital. Each participant was given the opportunity to act in the supported clinician role and the peer supporter role. Participants were given the opportunity to reflect and share approaches to interactions with each other.

In addition to this training, a one-hour presentation about the “Second Victim” phenomenon was presented at grand rounds, faculty and staff meetings, or other departmental meetings, to normalize the behavior of seeking support after an adverse event or medical error and to provide information on the Peer Support Program. The presentation included data from published studies describing the impact of adverse events on clinicians and methods for reaching out for support.

Selection of Peer Support Clinicians

In order to ensure clinician peer supporters represented a diverse population from procedural and diagnostic specialties, academic department chairs from all clinical departments were asked to nominate individuals they identified as having active listening skills and the ability to connect with peers during potentially emotionally charged conversations. Interested individuals could also nominate themselves. Nominated peer support clinicians were invited to participate in a training session. After completion of the initial training, nominated peer supporters were asked if they wished to continue in the program as a peer supporter. Nearly 40 clinician peer supporters, including members from emergency medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics, radiology, general surgery, neurology, anesthesiology, otolarnyngology, neurosurgery, obstetrics and gynecology, and ophthalmology participated in the full peer support training program and volunteered their time to support other clinicians. Given the relatively frequent turnover of residents and fellows, trainees were not considered for peer supporter roles. However, trainees are eligible to receive support from the PSP. Additionally, approximately 6 months after our initial training sessions, we recognized that many mid-level providers function like physicians and may benefit from being supported by other PAs, NPs or CRNAs. Therefore, we expanded our peer supporter pool to include mid-level providers.

Program Structure

Clinicians potentially in need of support were able to enter the program through several avenues. Clinicians could be referred by safety or risk staff if they demonstrated signs or symptoms of emotional impact during safety event investigations; clinicians could self-refer or be referred by a peer support provider. Despite making peer support resources available, some clinicians may not request help despite experiencing the emotional impact of a safety event. For clinicians who delay seeking assistance, requests for support often occurred once the individual’s work performance, personal relationships or home-life were impacted. In order to provide a consistent support resource to clinicians near the time of a serious event, the program’s referral process was further refined to proactively contact all clinicians involved in a serious medical error or adverse event.

After identification of a clinician involved in an event, the PSP directors (MZT, MAL, CG) match the clinician to an available peer supporter. Although no formal matching criteria were established, medical specialty (procedural vs. diagnostic), seniority, and individual clinician characteristics are considered when assigning peer supporters. When possible, individuals are not assigned peer supporters that practice in the exact same field or who are in a supervisory position to the individual.

Following identification of a clinician possibly in need of support, a PSP director contacts the clinician via an introductory email. The goal of this introduction is to normalize the need for support and to inform them that a peer supporter will contact them. Peer supporters make initial contact via email or phone. If the clinician accepts support, the peer supporter follows up to schedule a convenient time for further discussion. If the individual declined support, the peer supporter was encouraged to ask permission to follow up with the clinician in approximately one week to assess the clinician’s level of coping.

There are multiple time points when a clinician might need support. Our hospitals have a well established patient disclosure and resolution process to meet the needs of patients and families impacted by adverse events and medical error. Support for the clinician is available during the disclosure process, investigation, and development of interventions to prevent future events. Some clinicians find this to be a helpful step in the healing process.11 Additionally, support for the clinician is available if the event proceeds to litigation.

Peer supporters were trained to reassure clinicians that their role was to provide nonjudgmental assistance in identifying mechanisms to cope with the emotional consequences of events. The peer supporter serves to support the clinician’s natural resilience by identifying and encouraging positive coping mechanisms to work through the stressful event.17, 18 Clinicians are informed that the peer supporter does not keep notes of conversations and all conversations are confidential except in circumstances where they may be a danger to themselves or others. Conversations focus on the individual’s emotions and wellbeing and not on details of the event. Additionally, the support clinician seeks to help the individual understand that the stressor event does not define them as a clinician but that the experience can be used to improve healthcare systems and help prevent others from experiencing similar events.

At the conclusion of the conversation, the clinician is encouraged to contact the peer supporter if they wish to speak again; the supporter also requests permission to follow up in a few weeks if the clinician does not contact them. When necessary, peer supporters are able to provide clinicians additional resources for support including mental health professionals within the medical center as well as unaffiliated mental health resources.

Peer supporters are required to debrief with a PSP director after contact with an individual to ensure program accountability and oversight. During this debriefing, peer supporters confirm completion of initial contact and plans for next contact with the assigned clinician. Supporters discuss any concerns that they may have or recommendations regarding the need for a higher level of support. Additionally, in order to maintain skills among the peer supporter pool, monthly meetings or conference calls were held to share program updates and to allow peer supporters to share any approaches and lessons learned during their support conversations. This open forum allowed for rapid sharing of information if support efforts were met with resistance or discomfort by supporters or peers.

Results

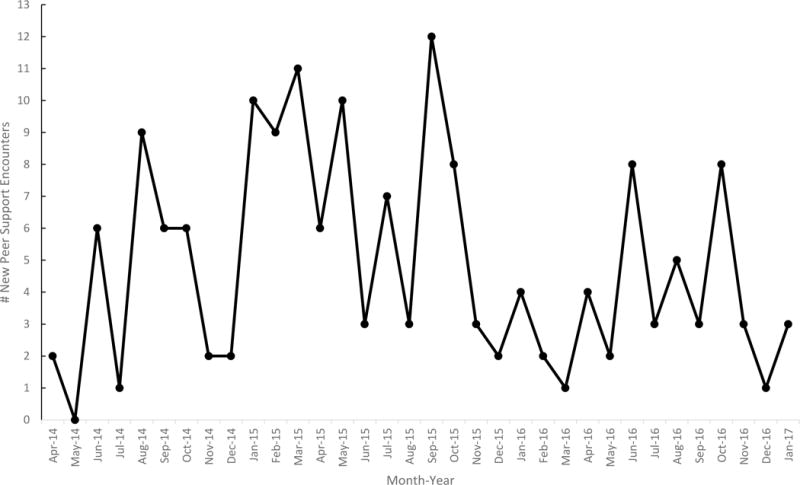

A total of 88 clinicians were nominated by department chairs or through self-nomination. After completion of training, 36 clinicians were included in the clinician peer supporter pool. Composition of the peer supporter pool by specialty is shown in Table 1. Clinicians from surgical or procedural specialties (general surgery, neurosurgery, otolaryngology, ophthalmology and obstetrics/gynecology) comprised 44.4% (n = 16) of the peer supporter pool. Between April 2014 and January 2017, 165 clinicians were referred to the WUSM Clinician Peer Support Program including 68 (41.2%) residents, 17 (10.3%) fellows, 70 (42.4%) faculty members, 6 (3.6%) NPs/PAs and 4 (2.4%) CRNAs. There was an average of 4.8 referrals per month (Range 0-12) (Table 1). Of the 165 clinicians referred, 17 (10.3%) declined follow-up from the PSP. Among those receiving support, the median number of interactions was 2 (Range 1-10). Among all individuals referred to the PSP, 16 (9.7%) required referral to a higher level of support.

Table 1.

Composition of Peer Supporter Pool

| Specialty | Peer Support Clinicians (n) |

|---|---|

| Anesthesia | 6 |

| Emergency Medicine | 2 |

| Internal Medicine | 5 |

| Neurology | 3 |

| Neurosurgery | 1 |

| Obstetrics & Gynecology | 2 |

| Ophthalmology | 1 |

| Otolaryngology | 4 |

| Pediatrics | 5 |

| Psychiatry | 2 |

| Radiology | 3 |

| Surgery | 2 |

Discussion

Current estimates suggest that a significant number of patients experience significant adverse events and errors resulting in harm each year.1–3 While much of the health care response focuses on supporting the patient and their families, the clinicians involved often become “second victims” of the event.6 It is common for clinicians to experience significant emotional distress following adverse events or medical errors including feelings of guilt, shame, loss of confidence, anxiety, fatigue and burnout.10–12 In order to address the needs of clinicians, the National Quality Forum and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement have recommended that healthcare organizations develop programs to support clinicians following adverse events and medical errors.4, 19 However, 90% of physicians report that their hospital or healthcare organization does not adequately support them in coping with stress following a medical error.10 Surveys of physicians have identified significant barriers that prevent physicians from receiving support.10, 14, 15 The peer support program described in this manuscript was designed specifically to address the needs of clinicians.

Several models for providing support to healthcare workers after involvement in an adverse event or medical error have been described.20–22 A survey of hospital risk managers found that many hospitals (N= 423, 73.6%) already have programs in place to support healthcare workers after adverse event. The majority (93.9%) of these programs are available to all employees regardless of role. Many of these programs (90.1%) fall within the umbrella of employee assistance programs (EAP).14 However, our own experience and that of others suggests that physicians infrequently utilize EAPs and are more comfortable seeking support from clinician peers.16, 20 Established programs demonstrate that physicians make up a small portion of individuals seeking support.20, 22, 23 Multiple barriers to physicians seeking support have been described including fears about confidentiality, impact on career and the lack of time.15 Within our organization, some clinicians have reported fears of stigmatization for utilizing EAP because of the perceived role EAPs play in addressing disruptive behavior, substance abuse, addiction and performance issues. Nearly 70% of physicians surveyed about barriers to receiving support voiced concerns about the stigma of mental health care.15 Additionally, physicians identify EAPs as one of the least frequently utilized resources during stressful situations while physician peers are among the most commonly identified resources for physicians faced with stressful circumstances.15

In many organizations, this peer-to-peer support occurs naturally without relying on a formal program. In order for these natural support relationships to be successful, an individual in need of support must be able to identify a peer to provide support and must be comfortable asking for help. Additionally, the peer providing support must have the necessary skill set to provide effective assistance. In our experience, local efforts by compassionate colleagues to support individuals following events frequently end too early. Our program is designed to remove some of these barriers and increase the likelihood of clinicians receiving support when needed and on an ongoing basis.

Our program has been successful in large part due to intentional programmatic development. Key elements of our program include development of a multidisciplinary team that includes members of legal and risk management departments, an iterative curricular development process based on accepted concepts of clinician resilience that provides training to peer supporters and a large peer support cohort comprised of physicians and mid-level providers. Lessons learned through our programmatic development may aid others seeking to develop clinician PSPs.

We found that having a multidisciplinary development team including members of legal and risk management departments was very helpful at a variety of levels. Our legal and risk management departments are supportive of our program given the low likelihood of legal risk and the benefit of adequately supporting the clinician. We had anticipated that individuals requesting support may have concerns about utilizing the PSP due to fears of future litigation; therefore, we addressed this in our initial conversations with them to allay any fears. However, we had not anticipated that potential peer supporters might be reluctant to join the program due to fears of being asked to testify about their conversations with peers. We addressed these concerns proactively in subsequent training sessions; we excused any peer supporters who were not comfortable with the minimal risk. To further minimize risk, peer supporters do not keep any written notes about their conversations. Legal and risk management departments should be engaged early to address concerns about discoverability of peer support discussions.

Although our peer supporter pool contains a large number of individuals (16, 44%) from surgical and procedural areas, regular engagement from these supporters has been challenging. Many of our peer supporters from procedural specialties have limited availability due to operative schedules, requiring us to continue to actively recruit additional peer supporters from these areas. Approximately 6 months after program initiation, we expanded the reach of the program to include mid-level providers.

Since initiating our program, we have tried several approaches to identify those clinicians most in need of support. As others have found, we learned that individuals rarely self-refer to support programs.16 Our initial approach relied upon referral from risk management and on identifying individuals who showed signs of emotional distress during the course of a safety event investigation. However, this approach missed many individuals or identified them late in the process. We modified our approach to initiate contact with all clinicians involved in serious safety events. While this approach identified additional individuals possibly in need of support, we may not have identified individuals involved in events that were not considered serious safety events, such as near misses.

In order to ensure long-term success of these programs, organizations should provide adequate resources to sustain the program. Our program was reliant on volunteer efforts from peer support leaders and clinicians. While our model was successful during initial program development, it is not sustainable long term. Over time, we experienced decreased participation in monthly meetings and calls designed to share program updates due to competing demands on the peer support clinicians who did not have any protected time for these efforts. Organizations seeking to replicate our program should seek to secure a financial commitment from their organizational leadership to ensure long-term program sustainability. Our program is limited to a single academic medical center that serves both adult and pediatric patient populations which may limit broad generalizability; however, we believe components of our program can inform development of local programs to support physicians and mid-level providers.

Adverse events and medical errors can have significant impact on the involved clinicians including feelings of guilt, shame, loss of confidence, anxiety, fatigue and burnout. While our program is a step forward in providing emotional support to clinicians involved in such events, many individuals do not receive the adequate support for healing and wellness. Although healthcare organizations may have programs in place to provide support to employees, they should assess whether these programs meet the specific needs of their physicians and mid-level providers. The creation of peer support programs can complement traditional EAPs to provide clinicians a safe environment that promotes healing after adverse events.

Figure 1.

Peer Support Encounters – April 2014 – January 2017

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all of the peer supporters who have given their time to provide support to their peers.

Sources of Funding:

Dr. Lane has received career development support from the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1TR000448, sub-award KL2TR000450, from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the NIH.

References

- 1.Classen DC, Resar R, Griffin F, et al. ‘Global trigger tool’ shows that adverse events in hospitals may be ten times greater than previously measured. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2011;30:581–589. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0190. 2011/04/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levinson DR. Adverse Events in Hospitals: National Incidence Among Medicare Beneficiaries. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Inspector General; 2010. (Report no. OEI-06-09-00090). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Institute of Medicine; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conway J, Federico F, Stewart K, et al. Respectful Management of Serious Clinical Adverse Events. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schiff G, Griswold P, Ellis BR, et al. Doing right by our patients when things go wrong in the ambulatory setting. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2014;40:91–96. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(14)40011-4. 2014/04/11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu AW. Medical error: the second victim. The doctor who makes the mistake needs help too. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2000;320:726–727. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.726. 2000/03/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christensen JF, Levinson W, Dunn PM. The heart of darkness: the impact of perceived mistakes on physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7:424–431. doi: 10.1007/BF02599161. 1992/07/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newman MC. The emotional impact of mistakes on family physicians. Archives of family medicine. 1996;5:71–75. doi: 10.1001/archfami.5.2.71. 1996/02/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallagher TH, Waterman AD, Ebers AG, et al. Patients’ and physicians’ attitudes regarding the disclosure of medical errors. Jama. 2003;289:1001–1007. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.8.1001. 2003/02/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waterman AD, Garbutt J, Hazel E, et al. The emotional impact of medical errors on practicing physicians in the United States and Canada. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33:467–476. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(07)33050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott SD, Hirschinger LE, Cox KR, et al. The natural history of recovery for the healthcare provider “second victim” after adverse patient events. Quality & safety in health care. 2009;18:325–330. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.032870. 2009/10/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.West CP, Huschka MM, Novotny PJ, et al. Association of perceived medical errors with resident distress and empathy: a prospective longitudinal study. Jama. 2006;296:1071–1078. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1071. 2006/09/07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Gerven E, Vander Elst T, Vandenbroeck S, et al. Increased Risk of Burnout for Physicians and Nurses Involved in a Patient Safety Incident. Med Care. 2016;54:937–943. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000582. 2016/05/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White AA, Brock DM, McCotter PI, et al. Risk managers’ descriptions of programs to support second victims after adverse events. Journal of healthcare risk management : the journal of the American Society for Healthcare Risk Management. 2015;34:30–40. doi: 10.1002/jhrm.21169. 2015/04/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu YY, Fix ML, Hevelone ND, et al. Physicians’ needs in coping with emotional stressors: the case for peer support. Archives of surgery (Chicago, Ill : 1960) 2012;147:212–217. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.312. 2011/11/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shapiro J, Galowitz P. Peer Support for Clinicians: A Programmatic Approach. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2016;91:1200–1204. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000001297. 2016/06/30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eley DS, Cloninger CR, Walters L, et al. The relationship between resilience and personality traits in doctors: implications for enhancing well being. PeerJ. 2013;1:e216. doi: 10.7717/peerj.216. 2013/11/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burlison JD, Scott SD, Browne EK, et al. The Second Victim Experience and Support Tool: Validation of an Organizational Resource for Assessing Second Victim Effects and the Quality of Support Resources. Journal of patient safety. 2014 doi: 10.1097/pts.0000000000000129. 2014/08/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Safe Practices for Better Healthcare–2010 Update: A Consensus Report. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum (NQF); 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edrees H, Connors C, Paine L, et al. Implementing the RISE second victim support programme at the Johns Hopkins Hospital: a case study. BMJ open. 2016;6:e011708. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011708. 2016/10/04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scott SD, Hirschinger LE, Cox KR, et al. Caring for our own: deploying a systemwide second victim rapid response team. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36:233–240. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(10)36038-7. 2010/05/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merandi J, Liao N, Lewe D, et al. Deployment of a Second Victim Peer Support Program: A Replication Study. Pediatric Quality & Safety. 2017;2:e031. doi: 10.1097/pq9.0000000000000031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirschinger LE, Scott SD, Hahn-Cover K. Clinician support: five years of lessons learned. Patient Saf Qual Healthcare. 2015 [Google Scholar]