Abstract

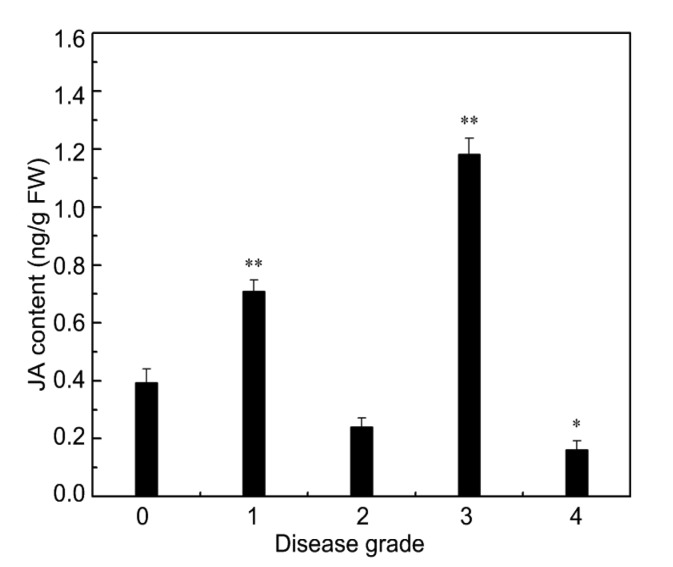

In plants, lipoxygenases (LOXs) play a crucial role in biotic and abiotic stresses. In our previous study, five 13-LOX genes of oriental melon were regulated by abiotic stress but it is unclear whether the 9-LOX is involved in biotic and abiotic stresses. The promoter analysis revealed that CmLOX09 (type of 9-LOX) has hormone elements, signal substances, and stress elements. We analyzed the expression of CmLOX09 and its downstream genes—CmHPL and CmAOS—in the leaves of four-leaf stage seedlings of the oriental melon cultivar “Yumeiren” under wound, hormone, and signal substances. CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS were all induced by wounding. CmLOX09 was induced by auxin (indole acetic acid, IAA) and gibberellins (GA3); however, CmHPL and CmAOS showed differential responses to IAA and GA3. CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS were all induced by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and methyl jasmonate (MeJA), while being inhibited by abscisic acid (ABA) and salicylic acid (SA). CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS were all induced by the powdery mildew pathogen Podosphaera xanthii. The content of 2-hexynol and 2-hexenal in leaves after MeJA treatment was significantly higher than that in the control. After infection with P. xanthii, the diseased leaves of the oriental melon were divided into four levels—levels 1, 2, 3, and 4. The content of jasmonic acid (JA) in the leaves of levels 1 and 3 was significantly higher than that in the level 0 leaves. In summary, the results suggested that CmLOX09 might play a positive role in the response to MeJA through the hydroperoxide lyase (HPL) pathway to produce C6 alcohols and aldehydes, and in the response to P. xanthii through the allene oxide synthase (AOS) pathway to form JA.

Keywords: 9-Lipoxygenase (9-LOX), Hydroperoxide lyase (HPL), Allene oxide synthase (AOS), Green leaf volatile, Jasmonic acid

1. Introduction

Lipoxygenases (LOXs, EC 1.13.11.12) are a group of non-heme iron-containing enzymes, which are widely distributed throughout animals, plants, and fungi (Liavonchanka and Feussner, 2006; Ivanov et al., 2010; Christensen and Kolomiets, 2011). In plants, LOXs are related to many biological processes, including growth and development (Keereetaweep et al., 2015), synthesis of aroma compounds (Shen et al., 2014), synthesis of ethylene (Griffiths et al., 1999), ripening and senescence (Hou et al., 2015), and they especially play a crucial role in defense against biotic and abiotic stresses (Wang et al., 2008; Maschietto et al., 2015). LOXs can catalyze the oxygenation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) with a Z,Z-1,4-pentadiene structure to form fatty acid hydroperoxides (Brash, 1999). These hydroperoxides act as substrates for seven downstream branches of the LOX pathway to form a wide variety of active compounds, collectively called oxylipins (Feussner and Wasternack, 2002). The hydroperoxide lyase (HPL) and allene oxide synthase (AOS) pathways responsible for green leaf volatiles (GLVs) and jasmonic acid (JA) production, respectively, are the predominant and comprehensible pathways activated in the stress response (Birkett et al., 2000). Overexpression of CsiHPL1 greatly enhances the resistance of tomatoes to fungal Aleuria aurantia lectin (AAL), which indicates that CsiHPL1 is involved in plant defense against fungal attack (Xin et al., 2014). The expression of AOS is greatly induced by wounding treatment and the level of JA in Arabidopsis wounding plants is limited by AOS expression (Park et al., 2002).

There are many studies suggesting that LOX gene expression and LOX activity are regulated by different stresses such as wounding, low and high temperatures, hormones, signaling substances, and biotic stress (Maccarrone et al., 2000; Porta et al., 2008; Bhardwaj et al., 2011; Christensen et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2013, 2015). In tomato plants, the expression of TomloxD has been rapidly induced by wounding (Heitz et al., 1997). ZmLOX10 in maize was up-regulated by wounding and cold stresses (Nemchenko et al., 2006). Drought stress could increase LOX activity dramatically in brassica seedlings (Alam et al., 2014). Salt stress could also significantly increase LOX activity in rice (Mostofa et al., 2015). In Arabidopsis, LOX3 was dramatically induced under salt treatment (Ding et al., 2016). The LOX activity of soybean zygotic embryos was increased significantly after indole acetic acid (IAA) treatment (Liu et al., 1991). CjLOX from Caragana jubata could be regulated by signal substances such as abscisic acid (ABA), salicylic acid (SA), and methyl jasmonate (MeJA) (Bhardwaj et al., 2011). The LOX activity of oriental melon seedlings was increased after treatment with ABA, SA, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and MeJA (Liu et al., 2016). Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) infection led to the up-regulated expression of LOX genes in Arabidopsis thaliana leaves (la Camera et al., 2009). DkLOX3-overexpression (DkLOX3-OX) in Arabidopsis showed more tolerance to Botrytis cinerea (Hou et al., 2018). In particular, the 9-LOX gene CaLOX1 was distinctively induced in pepper leaves (Capsicum annuum L.) that had been inoculated with Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria (Hwang and Hwang, 2010). Also, after X. campestris pv. malvacearum infection, high LOX activity supported cell death in cotton (Sayegh-Alhamdia et al., 2008).

Plant LOXs are encoded by multigene families (Andreou and Feussner, 2009) and classified as 9-LOXs and 13-LOXs, according to the position, at which oxygen is inserted into linoleic acid or linolenic acid (Feussner and Wasternack, 2002). In our previous study, we have identified 18 LOX genes in the melon genome (named CmLOX01–18) (Zhang et al., 2014). In addition, five 13-LOX genes were found to respond to abiotic stress and signal substances (Liu et al., 2016). However, the defense-related functions of 9-LOXs in oriental melon are still poorly understood. An oriental melon (Cucumis melon var. makuwa Makino) 9-LOX gene, CmLOX09, which encodes a 9-specific LOX, was isolated from melon fruits (Zhang et al., 2015). The phylogenetic analysis of CmLOX09 showed that it is closely related to cucumber CsLOX09, and responds to low temperatures and 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) (Yang et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2015). Moreover, the pepper 9-LOX gene CaLOX1 also plays a significant role in osmosis, drought, high salinity, and microbial pathogens’ stress responses (Lim et al., 2015). The promoter analysis revealed that the CmLOX09 promoter has various elements of abiotic stress, hormones, signal substances, and biotic stress. Therefore, we analyzed the effects of wounding, hormones treatments, signal substances treatments and inoculation with a powdery mildew pathogen Podosphaera xanthii on oriental melon seedlings in order to elucidate the role of CmLOX09 in various stress responses. Furthermore, the expression of two downstream genes CmHPL and CmAOS was measured. The GLVs of HPL-derived oxylipins served as signals to defend against wounding, fungal and insect attack (Christensen et al., 2013; Ameye et al., 2015). Based on the high-level expression patterns of CmLOX09 and CmHPL under MeJA treatment compared with other treatments, the levels of GLVs in leaves under MeJA treatment were determined in order to investigate whether CmLOX09 responded to MeJA through the HPL pathway to produce GLVs. Moreover, 13-LOXs have been shown to be associated with the production of JA in resistance to microbial pathogens (Hu et al., 2013). To test whether the 9-LOX gene CmLOX09 was involved in pathogen-induced production of JA, the levels of JA were measured after inoculation with P. xanthii.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plant materials and treatments

All the treatments were carried out with oriental melon (Cucumis melon var. makuwa Makino), cultivar “Yumeiren” (Changchun, China). Seedlings were grown in pots (compost:peat:soil=1:1:1) in a greenhouse (temperature 25 °C (day)/22 °C (night), natural light, relative humidity 60%–70%). The melon seedlings with a four-leaf stage were treated as follows.

To induce wounding, the four expanded true leaves were wounded with a pair of surgical scissors and the wounded leaves were collected, and the healthy leaves from uninjured seedlings were collected as controls. The third and fourth true leaves were sampled at 0, 0.5, 1.5, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h after treatment.

For hormone treatments, 100 μmol/L IAA and 100 μmol/L gibberellins (GA3) were applied to oriental melon seedlings (10 ml for each plant) and the control seedlings were sprayed with 0.1% (v/v) ethanol solution (10 ml for each plant). For all the seedlings, the third and fourth true leaves without veins were harvested at 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, 72, 120, and 168 h.

For signal substance treatments, seedlings were sprayed (10 ml for each seedling) with 100 μmol/L ABA, 5 mmol/L SA, 10 mmol/L H2O2, and 100 μmol/L MeJA, and the control seedlings of ABA, SA, and MeJA treatments were sprayed with 0.1% (v/v) ethanol solution (10 ml for each seedling), while the controls of H2O2 were sprayed with sterile water (10 ml for each seedling). Plants treated with MeJA were tightly sealed in a plastic bag. For all the seedlings, after 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, 72, 120, and 168 h the third and fourth true leaves without veins were harvested.

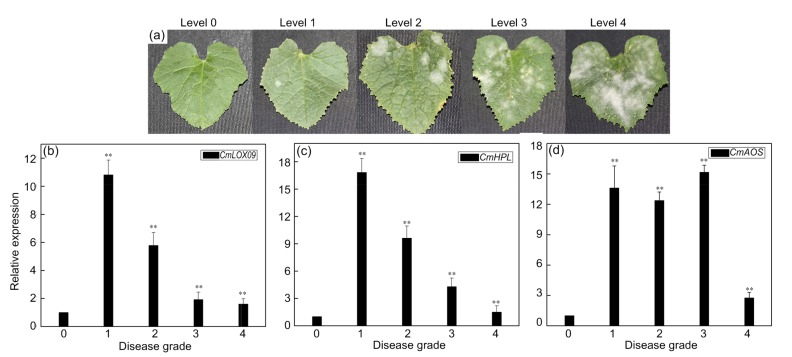

P. xanthii was collected from a naturally infected plant, and then true leaves were sprinkled in order to inoculate the melon seedlings sampled at different disease levels. The disease grade of inoculation with P. xanthii in the leaves of oriental melon was as follow: level 0, no lesions; level 1, a mild disease, lesion area 0%–25%; level 2, the onset of mild, lesion area 25%–50%; level 3, moderate incidence, lesion area 50%–75%; level 4, severe disease, lesion area >75%.

All plant materials were frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after collecting and stored at −80 °C until used.

2.2. Promoter analysis

Firstly, the 9-LOX gene CmLOX09 (GenBank: MELO3C0014482) and the NCBI program were used to search for the DNA skeleton of the CmLOX09. Secondly, the translation start site is defined as +1; the promoter sequence was 2000 bp upstream of the translation start site. Finally, the PLANT CARE software (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html) was used to analyze the response element of the promoter sequence (Fig. S1).

2.3. RNA extraction and gene expression analysis by qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from 0.5 g treated leaves under liquid nitrogen using the RNAprep Pure Plant Total RNA Extraction Kit (Kangwei, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 2 µg of RNA using the M-MLV RTase cDNA Synthesis Kit (TaKaRa, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primer sequences are listed in Table 1. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed in a 20-μl reaction volume using PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (Perfect Real Time) (TaKaRa, Tokyo, Japan) on an ABI PRISM 7500 Sequence-Detection System according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The PCR program was followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 34 s, 95 °C for 5 s, 60 °C for 1 min, and 95 °C for 30 s. A constitutively expressed 18S RNA gene was used as an internal reference. Three independent biological experiments were used as replicates for the qRT-PCR. The relative gene expression of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS was calculated using the 2−ΔΔ C T method.

Table 1.

Sequence of primers used for gene expression analysis by qRT-PCR

| Name | Oligonucleotide | Sequence |

| CmLOX09 | CmLOX09-F | 5'-CAGATCCATCTTGTGAAC-3' |

| CmLOX09-R | 5'-AGTTGGTAGAGTCATTCC-3' | |

| CmHPL | CmHPL-F | 5'-AGCGTTTTACTCCTCTTCTGGC-3' |

| CmHPL-R | 5'-CTTCTTCCTTCACGGTTGTCCT-3' | |

| CmAOS | CmAOS-F | 5'-TTCTTCCTCGTCTTCTTCCTCTC-3' |

| CmAOS-R | 5'-CAAATACTCTTCCCTCCCCTGAT-3' | |

| 18S RNA | 18sRNA-F | 5'-AAACGGCTACCACATCCA-3' |

| 18sRNA-R | 5'-CACCAGACTTGCCCTCCA-3' |

2.4. Green leaf volatile analysis

The GLVs of oriental melon leaves were analyzed using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS; Trace GC Ultra-ITQ 900, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). About 3 g of frozen leaves were ground and then transferred to a 20-ml glass vial (Thermo, USA), and 10 ml 20% (0.2 g/ml) NaCl solution was then added to the samples, along with 1-octanol (50 μl, 59.5 mg/L) as an internal standard. The mixture was completely homogenized and the glass vial was sealed with a crimp-top cap with a silicone/aluminium septa seal (20 mm, Thermo, USA). Then, the volatiles were extracted as described by Tang et al. (2015).

2.5. Extraction and determination of JA

Approximately 0.5–1.0 g fresh leaves were ground in liquid nitrogen to a fine powder, and an extraction buffer composed of isopropanol/hydrochloric acid was then added to the powder. The extract was shaken at 4 °C for 30 min. Dichloromethane was then added and shaken at 4 °C for 30 min and centrifuged at 13 000 r/min for 5 min at 4 °C. The lower organic phase was extracted, then dried with nitrogen and dissolved in 200 μl methanol (0.1% methanoic acid), followed by filtering with a 0.22-μm filter membrane. Finally, the product was analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS). Methanol (0.1% methanoic acid) was used to prepare different concentrations of standard solution. JA was analyzed using a ZORBAX SB-C18 (Agilent Technologies, USA) column (2.1 μm×150 μm; 3.5 μm). A volume of 2 μl of sample solution was injected for HPLC analysis. Methanol/0.1% methanoic acid and ultrapure water/0.1% methanoic acid served as mobile phase A and mobile phase B, respectively. The spray voltage was 4500 V, the pressure of the aux gas, nebulizer, and air curtain were 70, 65, and 15 psi (pound per square inch; 1 psi=6895 N/m2), respectively, and the atomizing temperature was 400 °C.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Three replicates of each treatment were carried out. The data were analyzed using the SPSS 13.0 statistics program, and significant differences were compared using the Duncan’s multiple range test for each experiment at P<0.05 level. The charts were made using Origin 8.0.

3. Results

3.1. Cis-regulatory element analysis of CmLOX09 promoter

The promoter analysis revealed that the CmLOX09 promoter has various cis-regulatory elements as shown in Fig. S1, such as light responsive elements (3-AF1 binding site, Box 4, ACE, AT1-motif), fungal elicitor responsive elements (Box-W1 element), hormone elements (P-box element), signal substance elements (ABRE element, TCA element), and ci-acting elements involved in defense and stress responsiveness (TC-rich repeats).

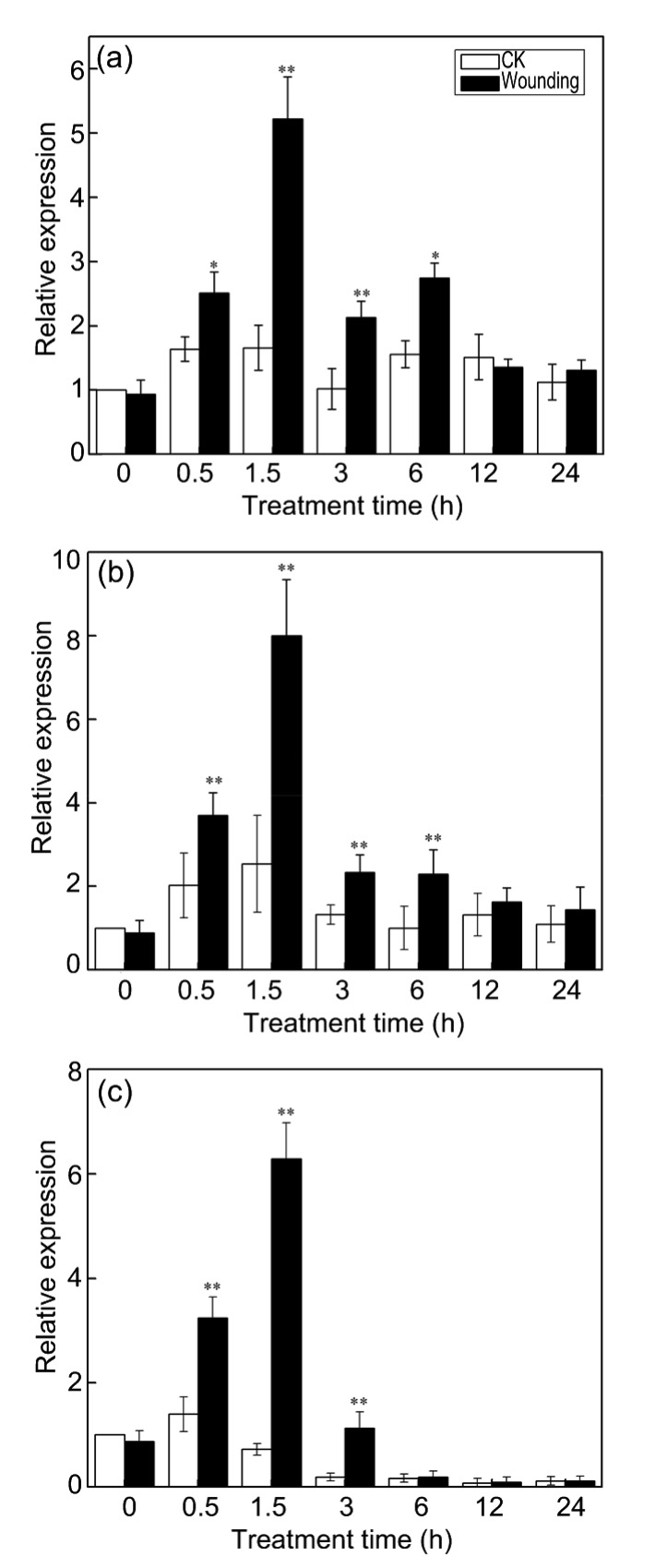

3.2. Effects of wounding on expression of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS in leaves of oriental melon

The expression patterns of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS after wounding treatment were examined to verify whether CmLOX09 is related to wounding treatment. After wounding treatment, the expression of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS began to increase at 0.5 h, and all reached the highest level at 1.5 h. The expression of CmLOX09 and CmHPL was both significantly higher than the controls at 0.5, 1.5, 3, and 6 h (Figs. 1a and 1b). The expression of CmAOS was significantly higher than the controls at 0.5, 1.5, and 3 h, and then returned to normal levels at 6 h (Fig. 1c). This finding suggested that CmLOX09 might play a positive role in plants against wounding treatment through the HPL and AOS pathways.

Fig. 1.

Expression patterns of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS after wounding treatment

(a) Expression pattern of CmLOX09 after wounding treatment. (b) Expression pattern of CmHPL after wounding treatment. (c) Expression pattern of CmAOS after wounding treatment. Data are presented as mean±standard error from three replicates with three biological repeats. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, compared to the respective control (CK) at each point

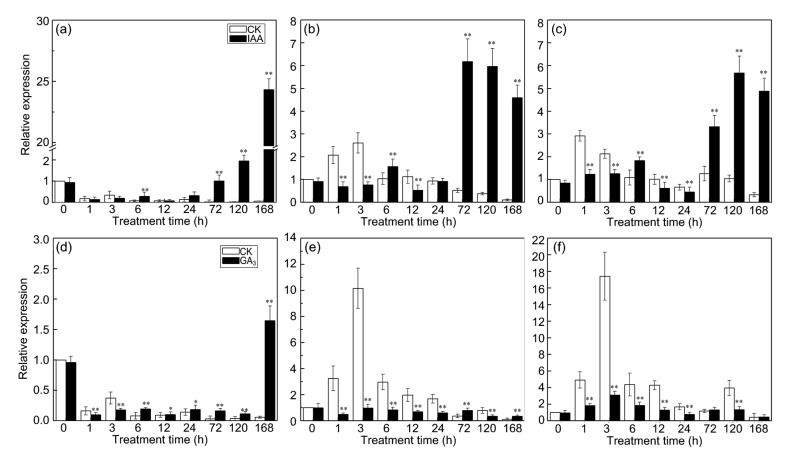

3.3. Effects of hormone treatments on expression of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS in leaves of oriental melon

Since there were cis-acting elements, such as hormone elements (P-box element) in the promoter of CmLOX09, we wanted to check whether the CmLOX09 was regulated by hormones. The expression of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS in oriental melon leaves at the four-leaf stage was analyzed in response to IAA and GA3.

After IAA treatment, CmLOX09 expression was significantly higher than the controls at 6, 72, 120, and 168 h, and reached its highest level at 168 h (Fig. 2a). Basically, the expression trends of CmHPL and CmAOS were similar; the expression was significantly higher than the controls at 6, 72, 120, and 168 h, while it was significantly lower than the controls at 1, 3, and 12 h (Figs. 2b and 2c).

Fig. 2.

Expression patterns of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS after IAA (100 μmol/L) and GA3 (100 μmol/L) treatments

(a) Expression patterns of CmLOX09 after IAA treatment. (b) Expression patterns of CmHPL after IAA treatment. (c) Expression patterns of CmAOS after IAA treatment. (d) Expression patterns of CmLOX09 after GA3 treatment. (e) Expression patterns of CmHPL after GA3 treatment. (f) Expression patterns of CmAOS after GA3 treatment. Data are presented as mean±standard error from three replicates with three biological repeats. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, compared to the respective control at each point

On the contrary, after GA3 treatment, the expression of CmLOX09 was down-regulated at 1 and 3 h. However, the expression of CmLOX09 was significantly higher than the controls from 6 to 168 h, and reached the highest level at 168 h (Fig. 2d). The expression of CmHPL was significantly lower than the controls at all time except at 72 h (Fig. 2e). The expression of CmAOS was significantly lower than the controls except at 72 and 168 h (Fig. 2f). Our results implied that CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS were differentially induced by hormones, which may be caused by the GA elements (P-box element) in the promoter of CmLOX09 showing a differential response to IAA and GA3

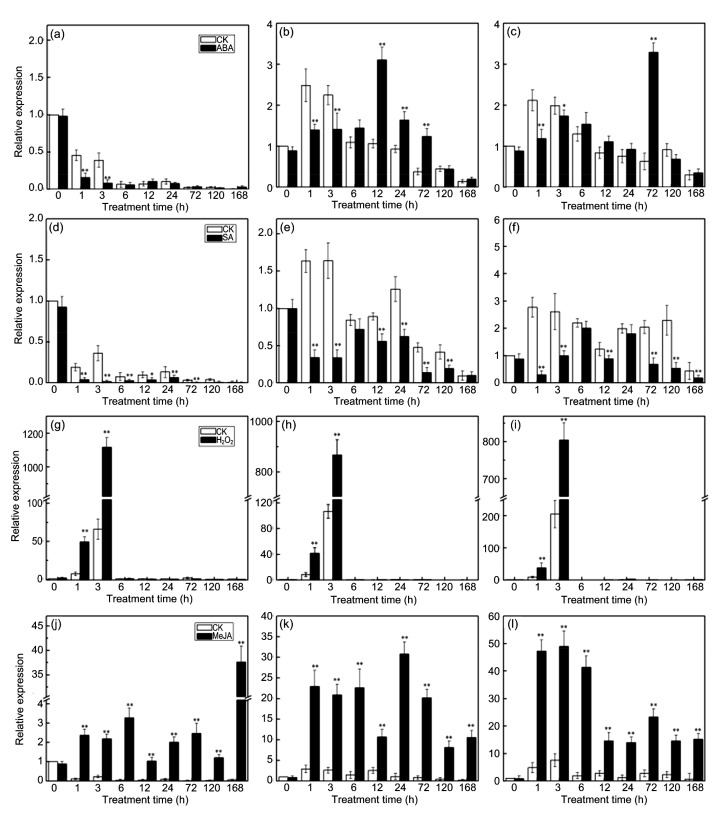

3.4. Effects of signal substances on expression of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS in leaves of oriental melon

ABA, SA, H2O2, and MeJA are important signaling molecules that regulate defense against stresses in plants (Yang et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2016). According to cis-acting elements, ABRE and TCA elements in the promoter of CmLOX09, to test whether the CmLOX09 was regulated by the signal molecules, the expression of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS in oriental melon leaves at the four-leaf stage in response to ABA, SA, H2O2, and MeJA was analyzed.

After ABA treatment, the expression of CmLOX09 was down-regulated significantly at 1 and 3 h (Fig. 3a). The expression of CmHPL reached its maximum level at 12 h and was significantly higher than the controls at 12, 24, and 72 h while being significantly lower than the controls at 1 and 3 h (Fig. 3b). The expression of CmAOS was significantly higher than the control at 72 h and reached the highest level while being significantly lower than the controls at 1 and 3 h (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Expression patterns of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS after ABA (100 μmol/L), SA (5 mmol/L), H2O2(10 mmol/L), and MeJA (100 μmol/L) treatments

(a) Expression patterns of CmLOX09 after ABA treatment. (b) Expression patterns of CmHPL after ABA treatment. (c) Expression patterns of CmAOS after ABA treatment. (d) Expression patterns of CmLOX09 after SA treatment. (e) Expression patterns of CmHPL after SA treatment. (f) Expression patterns of CmAOS after SA treatment. (g) Expression patterns of CmLOX09 after H2O2 treatment. (h) Expression patterns of CmHPL after H2O2 treatment. (i) Expression patterns of CmAOS after H2O2 treatment. (j) Expression patterns of CmLOX09 after MeJA treatment. (k) Expression patterns of CmHPL after MeJA treatment. (l) Expression patterns of CmAOS after MeJA treatment. Data are presented as mean±standard error from three replicates with three biological repeats. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, compared to the respective control at each point

The expression of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS was down-regulated by SA at different degrees. The expression of CmLOX09 was significantly lower than the controls from 1 to 72 h (Fig. 3d). The expression of CmHPL was significantly lower than the controls at the treatment time except at 6 and 168 h (Fig. 3e). The expression of CmAOS was significantly lower than the controls at the treatment time except at 6 and 24 h (Fig. 3f).

The expression of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS was largely up-regulated by H2O2. Basically, the expression trends of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS were similar and significantly higher than the controls at 1 and 3 h, showed its maximal level at 3 h and then declined at 6 h after treatment (Figs. 3g–3i). The expression of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS was up-regulated by MeJA in different degrees. The expression of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS was significantly higher than the controls at the treatment time, and reached its highest levels at 168, 24, and 3 h, respectively (Figs. 3j–3l).

In summary, the expression of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS was induced by H2O2 and MeJA, while inhibited by SA. The expression of CmLOX09 was down-regulated by ABA. The expression of CmHPL and CmAOS was down-regulated by ABA in the early stage while up-regulated in the late stage. Our results showed that CmLOX09 might respond to stresses through the production of signal substances such as H2O2 and MeJA rather than through ABA and SA.

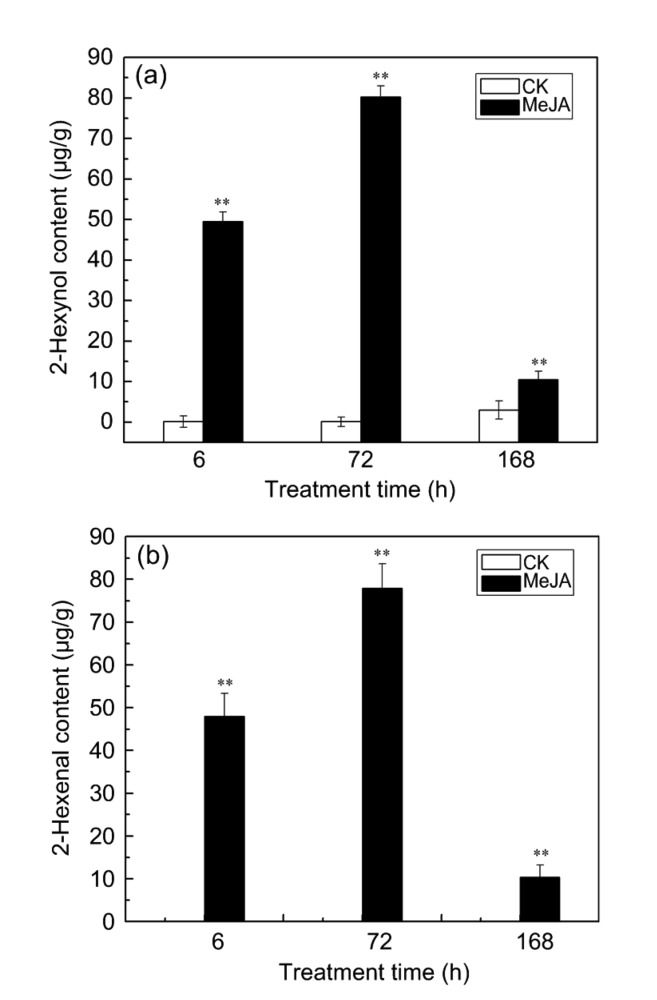

3.5. Effect of MeJA treatment on GLV content in leaves of oriental melon

Based on the expression patterns of CmLOX09 and CmHPL, we found that CmLOX09 and CmHPL exhibited a high-level expression under MeJA treatment compared with other treatments. We therefore hypothesized that CmLOX09 might be involved in MeJA-induced GLV synthesis. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the emission of GLVs in oriental melon leaves after MeJA treatment. The treatment time of 6, 72, and 168 h was selected to verify whether the accumulation of GLVs is induced by high-level CmHPL expression. The results of GC-MS showed that 10 alcohols, 3 aldehydes, 3 esters, 2 ketones, 1 other and 10 alcohols, 1 aldehyde, 5 esters, 1 ketone, 4 others were measured in the control and leaves with MeJA treatment, respectively (Table S1). However, after MeJA treatment, the content of 2-hexynol and 2-hexenal was significantly higher than that of the controls at 6, 72, and 168 h, with the highest level found at 72 h (Figs. 4a and 4b). Taken together, these findings suggested that CmLOX09 response to MeJA might occur through the HPL pathway to produce C6 alcohols and aldehydes. Hence, we speculated that high-level CmHPL expression induced by wounding and H2O2 might promote the accumulation of GLVs to respond to stress.

Fig. 4.

Levels of 2-hexynol and 2-hexenal in oriental melon treatment and control leaves after MeJA treatment

(a) 2-Hexynol release from oriental melon leaves after treatment at 6, 72, and 168 h. (b) 2-Hexenal release from oriental melon leaves after treatment at 6, 72, and 168 h. Data are presented as mean±standard error from three replicates with three biological repeats. ** P<0.01, compared to the respective control at each point

3.6. Effects of inoculation with P. xanthii on expression of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS in leaves of oriental melon

Similarly, there was a fungal elicitor responsive element in the promoter of CmLOX09. To investigate whether CmLOX09 was regulated by fungus, the expression of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS in oriental melon leaves after inoculation with P. xanthii was analyzed. As shown in Fig. 5, the expression of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS was significantly induced by P. xanthii. The expression of CmLOX09 and CmHPL was strongly induced at the mild morbidity level and later tended to be stable but also significantly higher than that at level 0 (Figs. 5b and 5c). The expression of CmAOS was higher in the incidence levels of 1, 2, and 3 than in level 4; however, the expression of level 4 was also significantly higher than that of level 0 (Fig. 5d). These findings indicated that the 9-LOX gene CmLOX09 was involved in biotic stress and might respond to this stress through the HPL or AOS pathway.

Fig. 5.

Expression patterns of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS after inoculation with Podosphaera xanthii treatments

(a) Different disease grades in oriental melon leaves after inoculated with P. xanthii. (b) Expression patterns of CmLOX09 after inoculated with P. xanthii. (c) Expression patterns of CmHPL after inoculated with P. xanthii. (d) Expression patterns of CmAOS after inoculated with P. xanthii. Numbers indicate the different disease grades (0, no lesions; 1, a mild disease, lesion area 0%–25%; 2, the onset of mild, lesion area 25%–50%; 3, moderate incidence, lesion area 50%–75%; 4, severe disease, lesion area >75%). Data are presented as mean±standard error from three replicates with three biological repeats. ** P<0.01 compared to the healthy leaves (0)

3.7. Effect of inoculation with P. xanthii on content of JA in leaves of oriental melon

Studies showed that 13-LOXs were involved in JA accumulation in defense against microbial pathogens (Hu et al., 2013). In this study, the endogenous JA, after inoculation with P. xanthii, was determined to verify whether the 9-LOX gene CmLOX09 was involved in the fungus-induced production of JA. The level of JA in diseased leaves was analyzed using HPLC-MS/MS (Fig. S2). As expected, the content of JA in levels 1 and 3 was significantly higher than that in level 0, and the content of JA in level 4 was significantly lower than that in level 0. However, the content of JA in level 2 did not differ from that in level 0, and the content of JA in diseased leaves was basically consistent with the trend of CmAOS expression (Fig. 6). Collectively, these findings demonstrated that the CmLOX09 response to P. xanthii might work through the AOS pathway to form JA. Whereas, based on the expression patterns of CmLOX09 and CmHPL, the possibility that the CmLOX09 response to P. xanthii occurs through the HPL pathway to produce GLVs could not be denied.

Fig. 6.

Level of JA in oriental melon leaves after inoculation with Podosphaera xanthii

Data are presented as mean±standard error from three replicates with three biological repeats. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, compared to the healthy leaves (0)

4. Discussion

The promoter analysis indicated that the CmLOX09 promoter contained stress response element TC-rich repeats, and the expression pattern of CmLOX09 on hormones, signal substances, and fungi stress was consistent with the prediction results of the promoter analysis. The CmLOX09 promoter had a P-box element and the expression was induced by GA3. CmLOX09 had ABRE and TCA elements and that the expression was inhibited by ABA and SA may be due to the response elements playing a negative role in the expression of CmLOX09. CmLOX09 had Box-W1 elements and its expression was induced by P. xanthii. Although there were no wounding or MeJA elements, the results showed that CmLOX09 was induced by wounding and MeJA.

To date, the best characterized LOX pathways are the HPL and AOS pathways, which were involved in the stress response. The GLVs produced by the HPL pathway played a vital role in defense against herbivores, and showed a certain antibacterial activity (Kallenbach et al., 2011). ZmLOX10 is involved in the wound-induced regulation of GLV biosynthesis (Christensen et al., 2013). LOX-H1 co-suppression decreased the release of GLVs (León et al., 2002). Similar to GLVs, the synthesis of JA, by the AOS pathway, as a signal substance was also involved in the defense response. Studies showed that the tomato TomloxD was involved in wound-induced JA biosynthesis (Yan et al., 2013). The LOX activity increased and the JA content accumulated dramatically in a short time in Arabidopsis thaliana leaves by wounding treatment (Bell et al., 1995). Antisense expression of NaLOX3 significantly reduced wound-induced JA accumulation (Halitschke and Baldwin, 2003). Ginseng responded to wounding that may be involved in the production of GLVs and JA at the wounded sites (Bae et al., 2016). In this study, the expression of CmLOX09 and its downstream genes CmHPL and CmAOS was all induced by wounding, suggesting that CmLOX09 may respond to wounding by both HPL and AOS pathways.

LOXs showed a differential response to hormones. Ethylene, IAA, GA3, and 6-benzylaminopurine (6-BA) are well-known hormones that participate in plant biological processes. Previous studies reported that CaLOX1 expression was significantly induced by ethylene treatment. In this study, CmLOX09 was up-regulated in the late stage of IAA and GA3 treatments; interestingly, CmHPL and CmAOS were up-regulated by IAA treatment and down-regulated by GA3 treatment. The LOX activity of soybean was greatly increased by IAA treatment (Liu et al., 1991). After GA3 treatment, LOX activity was inhibited, the expression of DkLOX01 and DkLOX03 was down-regulated, and then fruit ripening was delayed and fruit firmness was increased (Lv et al., 2014). Studies indicated that various LOX member responses to IAA and GA3 were different, while the specific mechanism still remains unclear.

ABA, SA, H2O2, and MeJA are central signaling molecules in the defense responses to abiotic stresses (Neill et al., 2002; Durrant and Dong, 2004; Zhang et al., 2006; Guo and Stotz, 2007). Studies showed that after ABA, SA, H2O2, and MeJA treatments, CmLOX09 responded rapidly, and the two downstream genes CmHPL and CmAOS actively participated in the stress. The expression of CmLOX09 was inhibited by ABA, but the expression of CmHPL and CmAOS was induced by ABA. Previous studies showed that CmLOX10 and CmLOX12 were up-regulated by ABA; meanwhile, CmLOX13 and CmLOX18 were down-regulated by ABA (Liu et al., 2016). ZmLOX6 declined dramatically starting at 1 h and reached its lowest level at 6 h after treatment with ABA (Gao et al., 2008). In this study, the expression of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS was down-regulated by SA. The expression of CmLOX09 was significantly inhibited from 1 to 72 h. Our previous study showed that only CmLOX12 was induced by SA among the five 13-LOXs; others were inhibited by SA (Liu et al., 2016). However, the 9-LOX gene CaLOX1 was induced by SA treatment (Hwang and Hwang, 2010). The specific reasons for the above differences are not clear; it may be caused by the difference between species and genes. The expression of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS was strongly induced by H2O2 at 3 h and declined after this time. H2O2 was added to the medium and the LOX gene expression and activity of lentil in the roots were increased to some extent (Maccarrone et al., 2000). The expression of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS was induced by MeJA. The expression of CsLOX2 was rapidly up-regulated with MeJA and reached its maximal level up to 100-fold at 3 h after treatment (Yang et al., 2012). CjLOX was strongly induced after spraying with MeJA (Bhardwaj et al., 2011).

Furthermore, based on the expression patterns of the three genes after signal substance treatment, we also investigated the emission of GLVs at 6, 72, and 168 h after MeJA treatment. The 2-hexynol and 2-hexenal content was significantly higher than that of the controls in oriental melon leaves in response to MeJA treatment; these data suggested that CmLOX09 may contribute to the production of C6 volatiles. After wounding treatment, the levels of Z-3-hexenal and Z-3-hexan-1-ol in the leaves of two LOX lines and wild type (WT) plants were significantly higher than those in the untreated leaves; however, the emission of Z-3-hexenal and Z-3-hexan-1-ol from transgenic plants did not result from levels released by the WT plant—this finding suggested that OsHI-LOX does not supply substrates for the production of GLVs in rice (Zhou et al., 2009). The LOX10-2 and LOX10-3 mutants provide substrates for the HPL pathway for GLV production in maize leaves in response to wounding or herbivory by Salix exigua (Christensen et al., 2013).

The 9-LOX gene NaLOX1 was induced in tobacco leaves infected with Phytophtora parasitica var. nicianae (Rancé et al., 1998). The 9-LOX gene GhLOX1 is associated with the hypersensitive reaction of cotton cell death responses to X. campestris pv. malvacearum (Marmey et al., 2007). The CaLOX1 of pepper was distinctively induced by X. campestris pv. vesicatoria, the number of cell death reactions decreased, and it was more susceptible to infection by pathogens in CaLOX1 silence pepper plant, which indicated that CaLOX1 was involved in the defense response of pepper to pathogenic microorganisms and cell death response (Hwang and Hwang, 2010). In the present study, after inoculation with P. xanthii, the expression of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS at different disease levels was significantly higher than that at level 0, which indicated that CmLOX09 was involved in the response to fungus.

Overexpression of TomloxD in transgenic tomatoes increased the content of endogenous JA and enhanced resistance to Cladosporium fulvum compared with non-transformed tomato plants, which suggested that TomloxD was involved in the synthesis of JA (Hu et al., 2013). Tomato plants with suppressed expression of the TomloxD gene have diminished LOX activity and the content of endogenous JA, which finally lead to increase in their susceptibility to microbial pathogens (Hu et al., 2015). Antisense expression of AtLOX2 decreased wound-induced JA accumulation (Bell et al., 1995). CMV inoculation increased the expression of two LOXs genes that participate in JA biosynthesis (la Camera et al., 2009). In Arabidopsis, LOX3 and LOX4 contribute to JA synthesis (Chauvin et al., 2016). In this study, the expression of CmLOX09 was strongly induced by P. xanthii, JA analysis showed that levels 1 and 3 contain higher endogenous JA compared with the level 0, the trend of JA was similar to the expression pattern of CmAOS, and the results indicated that the disease leaves might response to fungal stress by the 9-LOX-AOS pathway; however, the role of CmLOX09 in responses to biotic and abiotic stress needed to be verified using gene editing or overexpressed technique. Since lipid peroxidation closely related to LOX, we will measure malondialdehyde (MDA) or thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) in next work.

5. Conclusions

Here we reported the expression of CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS in the leaves of melon seedlings that were regulated by wounding, hormones (IAA, GA3), signal substances (ABA, SA, H2O2, MeJA), and biotic stresses (P. xanthii), which indicated that CmLOX09, CmHPL, and CmAOS were all induced by mechanical wounding and differentially induced by hormones and signal substances. In addition, we analyzed the content of GLVs after MeJA treatment and the content of JA after inoculation with P. xanthii. Taken together, these results implied that the CmLOX09 response to MeJA might occur through the HPL pathway to produce C6 alcohols and aldehydes; and the CmLOX09 response to P. xanthii might occur through the AOS pathway to form JA. Currently, the molecular mechanism of the CmLOX09-mediated pathway still remains unclear in plant responses. Moreover, the relationship between CmLOX09 and signal molecules is needed to be clarified. In further studies we will use transgenic plant to better understand the role of CmLOX09 in responses to biotic and abiotic stresses.

List of electronic supplementary materials

Cis-regulatory elements analysis of CmLOX09 promoter

Level of JA in oriental melon leaves after inoculation with Podosphaera xanthii analyzed with HPLC-MS/MS

Emission of GLVs in control and MeJA treatment leaves at 6, 72, and 168 h

Footnotes

Project supported by the China Agriculture Research System (No. CARS-25) and the Shenyang Science and Technology Project (No. 17-143-3-00), China

Electronic supplementary materials: The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1631/jzus.B1700388) contains supplementary materials, which are available to authorized users

Compliance with ethics guidelines: Li-jun JU, Chong ZHANG, Jing-jing LIAO, Yue-peng LI, and Hong-yan QI declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Alam MM, Nahar K, Hasanuzzaman M, et al. Exogenous jasmonic acid modulates the physiology, antioxidant defense and glyoxalase systems in imparting drought stress tolerance in different Brassica species . Plant Biotechnol Rep. 2014;8(3):279–293. doi: 10.1007/s11816-014-0321-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ameye M, Audenaert K, de Zutter N, et al. Priming of wheat with the green leaf volatile Z-3-hexenyl acetate enhances defense against Fusarium graminearum but boosts deoxynivalenol production. Plant Physiol. 2015;167(4):1671–1684. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreou A, Feussner I. Lipoxygenases–structure and reaction mechanism. Phytochemistry. 2009;70(13-14):1504–1510. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bae KS, Rahimi S, Kim YJ, et al. Molecular characterization of lipoxygenase genes and their expression analysis against biotic and abiotic stresses in Panax ginseng . Eur J Plant Pathol. 2016;145(2):331–343. doi: 10.1007/s10658-015-0847-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell E, Creelman RA, Mullet JE. A chloroplast lipoxygenase is required for wound-induced jasmonic acid accumulation in Arabidopsis . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(19):8675–8679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhardwaj PK, Kaur J, Sobti RC, et al. Lipoxygenase in Caragana jubata responds to low temperature, abscisic acid, methyl jasmonate and salicylic acid. Gene. 2011;483(1-2):49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birkett MA, Campbell CAM, Chamberlain K, et al. New roles for cis-jasmone as an insect semiochemical and in plant defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(16):9329–9334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160241697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brash AR. Lipoxygenases: occurrence, functions, catalysis, and acquisition of substrate. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(34):23679–23682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.23679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chauvin A, Lenglet A, Wolfender JL, et al. Paired hierarchical organization of 13-lipoxygenases in Arabidopsis . Plants. 2016;5(2):16. doi: 10.3390/plants5020016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christensen SA, Kolomiets MV. The lipid language of plant–fungal interactions. Fungal Genet Biol. 2011;48(1):4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christensen SA, Nemchenko A, Borrego E, et al. The maize lipoxygenase, ZmLOX10, mediates green leaf volatile, jasmonate and herbivore-induced plant volatile production for defense against insect attack. Plant J. 2013;74(1):59–73. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding H, Lai JB, Wu Q, et al. Jasmonate complements the function of Arabidopsis lipoxygenase3 in salinity stress response. Plant Sci. 2016;244:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durrant WE, Dong X. Systemic acquired resistance. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2004;42:185–209. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.42.040803.140421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feussner I, Wasternack C. The lipoxygenase pathway. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2002;53:275–297. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.100301.135248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao XQ, Stumpe M, Feussner I, et al. A novel plastidial lipoxygenase of maize (Zea mays) ZmLOX6 encodes for a fatty acid hydroperoxide lyase and is uniquely regulated by phytohormones and pathogen infection. Planta. 2008;227(2):491–503. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0634-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffiths A, Barry C, Alpuche-Solis AG, et al. Ethylene and developmental signals regulate expression of lipoxygenase genes during tomato fruit ripening. J Exp Bot. 1999;50(335):793–798. doi: 10.1093/jxb/50.335.793. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo XM, Stotz HU. Defense against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in Arabidopsis is dependent on jasmonic acid, salicylic acid, and ethylene signaling. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2007;20(11):1384–1395. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-11-1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halitschke R, Baldwin LT. Antisense LOX expression increases herbivore performance by decreasing defense responses and inhibiting growth-related transcriptional reorganization in Nicotiana attenuata . Plant J. 2003;36(6):794–807. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heitz T, Bergey DR, Ryan CA. A gene encoding a chloroplast-targeted lipoxygenase in tomato leaves is transiently induced by wounding, systemin, and methyl jasmonate. Plant Physiol. 1997;114(3):1085–1093. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.3.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hou YL, Meng K, Han Y, et al. The persimmon 9-lipoxygenase gene DkLOX3 plays positive roles in both promoting senescence and enhancing tolerance to abiotic stress. Front Plant Sci, 6:1073. 2015 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.01073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hou YL, Bai QY, Meng K, et al. Overexpression of persimmon 9-lipoxygenase DkLOX3 confers resistance to Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 and Botrytis cinerea in Arabidopsis . Plant Growth Regul. 2018;84(1):179–189. doi: 10.1007/s10725-017-0331-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu TZ, Zeng H, Hu ZL, et al. Overexpression of the tomato 13-lipoxygenase gene TomloxD increases generation of endogenous jasmonic acid and resistance to Cladosporium fulvum and high temperature. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 2013;31(5):1141–1149. doi: 10.1007/s11105-013-0581-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu TZ, Hu ZL, Zeng H, et al. Tomato lipoxygenase D involved in the biosynthesis of jasmonic acid and tolerance to abiotic and biotic stress in tomato. Plant Biotechnol Rep. 2015;9(1):37–45. doi: 10.1007/s11816-015-0341-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hwang IS, Hwang BK. The pepper 9-lipoxygenase gene CaLOX1 functions in defense and cell death responses to microbial pathogens. Plant Physiol. 2010;152(2):948–967. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.147827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ivanov I, Heydeck D, Hofheinz K, et al. Molecular enzymology of lipoxygenases. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;503(2):161–174. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kallenbach M, Gilardoni PA, Allmann S, et al. C12 derivatives of the hydroperoxide lyase pathway are produced by product recycling through lipoxygenase-2 in Nicotiana attenuata leaves. New Phytol. 2011;191(4):1054–1068. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keereetaweep J, Blancaflor EB, Hornung E, et al. Lipoxygenase-derived 9-hydro(pero)xides of linoleoylethanolamide interact with ABA signaling to arrest root development during Arabidopsis seedling establishment. Plant J. 2015;82(2):315–327. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.la Camera S, Balagué C, Göbel C, et al. The Arabidopsis Patatin-like protein 2 (PLP2) plays an essential role in cell death execution and differentially affects biosynthesis of oxylipins and resistance to pathogens. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2009;22(4):469–481. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-22-4-0469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.León J, Royo J, Vancanneyt G, et al. Lipoxygenase H1 gene silencing reveals a specific role in supplying fatty acid hydroperoxides for aliphatic aldehyde production. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(1):416–423. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107763200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liavonchanka A, Feussner I. Lipoxygenases: occurrence, functions and catalysis. Plant Physiol. 2006;163(3):348–357. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim CW, Han SW, Hwang IS, et al. The pepper lipoxygenase CaLOX1 plays a role in osmotic, drought and high salinity stress response. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015;56(5):930–942. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcv020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu JY, Zhang C, Shao Q, et al. Effects of abiotic stress and hormones on the expressions of five 13-CmLOXs and enzyme activity in oriental melon (Cucumis melo var. makuwa Makino) J Integr Agric. 2016;15(2):326–338. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(15)61135-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu WN, Hildebrand DF, Grayburn WS, et al. Effects of exogenous auxins on expression of lipoxygenases in cultured soybean embryos. Plant Physiol. 1991;97(3):969–976. doi: 10.1104/pp.97.3.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lv JY, Rao JP, Zhu YM, et al. Cloning and expression of lipoxygenase genes and enzyme activity in ripening persimmon fruit in response to GA and ABA treatments. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2014;92:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2014.01.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maccarrone M, van Zadelhoff G, Veldink GA, et al. Early activation of lipoxygenase in lentil (Lens culinaris) root protoplasts by oxidative stress induces programmed cell death. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267(16):5078–5084. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marmey P, Jalloul A, Alhamdia M, et al. The 9-lipoxygenase GhLOX1 gene is associated with the hypersensitive reaction of cotton Gossypium hirsutum to Xanthomonas campestris pv malvacearum . Plant Physiol Biochem. 2007;45(8):596–606. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maschietto V, Marocco A, Malachova A, et al. Resistance to Fusarium verticillioides and fumonisin accumulation in maize inbred lines involves an earlier and enhanced expression of lipoxygenase (LOX) genes. J Plant Physiol. 2015;188:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mostofa MG, Hossain MA, Fujita M. Trehalose pretreatment induces salt tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedlings: oxidative damage and co-induction of antioxidant defense and glyoxalase systems. Protoplasma. 2015;252(2):461–475. doi: 10.1007/s00709-014-0691-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neill SJ, Desikan R, Clarke A, et al. Hydrogen peroxide and nitric oxide as signalling molecules in plants. J Exp Bot. 2002;53(372):1237–1247. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/53.372.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nemchenko A, Kunze S, Feussner I, et al. Duplicate maize 13-lipoxygenase genes are differentially regulated by circadian rhythm, cold stress, wounding, pathogen infection, and hormonal treatments. J Exp Bot. 2006;57(14):3767–3779. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park JH, Halitschke R, Kim HB, et al. A knock-out mutation in allene oxide synthase results in male sterility and defective wound signal transduction in Arabidopsis due to a block in jasmonic acid biosynthesis. Plant J. 2002;31(1):1–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Porta H, Figueroa-Balderas RE, Rocha-Sosa M. Wounding and pathogen infection induce a chloroplast-targeted lipoxygenase in the common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Planta. 2008;227(2):363–373. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0623-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rancé I, Fournier J, Esquerré-Tugayé MT. The incompatible interaction between Phytophthora parasitica var.nicotianae race 0 and tobacco is suppressed in transgenic plants expressing antisense lipoxygenase sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(11):6554–6559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sayegh-Alhamdia M, Marmey P, Jalloul A, et al. Association of lipoxygenase response with resistance of various cotton genotypes to the bacterial blight disease. J Phytopathol. 2008;156(9):542–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0434.2008.01409.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shen JY, Tieman D, Jones JB, et al. A 13-lipoxygenase, TomloxC, is essential for synthesis of C5 flavour volatiles in tomato. J Exp Bot. 2014;65(2):419–428. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tang YF, Zhang C, Cao SX, et al. The effect of CmLOXs on the production of volatile organic compounds in four aroma types of melon (Cucumis melo) PLoS ONE. 2015;10(11):e0143567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang R, Shen WB, Liu LL, et al. A novel lipoxygenase gene from developing rice seeds confers dual position specificity and responds to wounding and insect attack. Plant Mol Biol. 2008;66(4):401–414. doi: 10.1007/s11103-007-9278-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xin ZJ, Zhang LP, Zhang ZQ, et al. A tea hydroperoxide lyase gene, CsiHPL1, regulates tomato defense response against Prodenia litura (Fabricius) and Alternaria alternata f. sp. lycopersici by modulating green leaf volatiles (GLVs) release and jasmonic acid (JA) gene expression. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 2014;32(1):62–69. doi: 10.1007/s11105-013-0599-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan LH, Zhai QZ, Wei JN, et al. Role of tomato lipoxygenase D in wound-induced jasmonate biosynthesis and plant immunity to insect herbivores. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(12):e1003964. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang XY, Jiang WJ, Yu HJ. The expression profiling of the lipoxygenase (LOX) family genes during fruit development, abiotic stress and hormonal treatments in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(2):2481–2500. doi: 10.3390/ijms13022481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang C, Jin Y, Liu JY, et al. The phylogeny and expression profiles of the lipoxygenase (LOX) family genes in the melon (Cucumis melo L.) genome. Scientia Horticulturae. 2014;170:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2014.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang C, Shao Q, Cao SX, et al. Effects of postharvest treatments on expression of three lipoxygenase genes in oriental melon (Cucumis melo var. makuwa Makino) Postharvest Biol Technol. 2015;110:229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2015.08.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang JH, Jia WS, Yang JC, et al. Role of ABA in integrating plant responses to drought and salt stresses. Field Crop Res. 2006;97(1):111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2005.08.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhou GX, Qi JF, Ren N, et al. Silencing OsHI-LOX makes rice more susceptible to chewing herbivores, but enhances resistance to a phloem feeder. Plant J. 2009;60(4):638–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cis-regulatory elements analysis of CmLOX09 promoter

Level of JA in oriental melon leaves after inoculation with Podosphaera xanthii analyzed with HPLC-MS/MS

Emission of GLVs in control and MeJA treatment leaves at 6, 72, and 168 h