Abstract

Provision of effective contraception to HIV positive women of reproductive age is critical to effective management of HIV infection and prevention of both vertical and horizontal HIV transmission in developing countries. This exploratory retrospective study examines contraceptive use during the prolonged postpartum period in a sample of 285 HIV positive and HIV negative women who gave birth at four rural maternity clinics in a high HIV-prevalence region in Mozambique. Multivariate analyses show no significant variations by HIV status in contraceptive timing (mean time to first contraceptive use of 7.1 months) or prevalence (31% at time of survey) but detect a moderating effect of fertility intentions: while HIV status makes no difference for women wishing to stop childbearing, among women who want to continue having children or are unsure about their reproductive plans, HIV positive status is associated with higher likelihood of contraceptive use. Regardless of HIV status, virtually no condom use is reported. These results are situated within the context of a rapidly widening access to postpartum antiretroviral therapy in the study site and similar sub-Saharan settings.

Background and conceptualization

Promotion of family planning to avoid unintended pregnancies is critical for improving health and wellbeing of HIV positive women and for effective prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (Andia et al., 2009; Habte & Namasasu, 2015; Petruney, Robinson, Reynolds, Wilcher, & Cates, 2008; Reynolds, Steiner, & Cates, 2005; Wilcher, Cates, & Gregson 2009). Yet, despite considerable overall advances in the provision of family planning services to both HIV positive and HIV negative women throughout sub-Saharan Africa, contraceptive use on the sub-continent remains limited (Darroch & Singh, 2013; Khan, Mishra, Arnold, & Abderrahim, 2007). In fact, in some countries contraceptive prevalence has recently stagnated and even declined, and unmet need for family planning in the region remains highest in the world (Cleland, Harbison, & Shah, 2014), with less than half of sub-Saharan women who said that they would like to stop or postpone childbearing using contraception (Sedgh, Hussain, Bankole, & Singh, 2007). As a result, unintended pregnancies are common (McCoy et al., 2014; Singh, Sedgh, & Hussain, 2010), compromising the health and well-being of women, children, and families.

Postpartum contraceptive use is particularly low (Winfrey and Rakesh, 2014). It is often hindered by what is said to be traditional practice of prolonged post-partum abstinence; accordingly, health care providers rarely encourage couples to start contraception early because of perceived low risks of conception. Besides, the benefits of antenatal and early postnatal contraceptive advice for postpartum contraceptive uptake are still debated (e.g., Engin-Üstün et al., 2007; Glazer, Wolf, & Gorby, 2011; Smith, van de Spuy, Cheng, Elton, & Glasier, 2002). Yet postpartum contraception has considerable potential in preventing unwanted or mistimed early repeat pregnancies, especially in a context of rapidly eroding traditional post-partum practices (Cleland, Shah, & Daniele, 2015). Moreover, prenatal and perinatal periods, when many women are typically in frequent contact with health providers, offer ideal opportunities for effective family planning counselling (e.g., Rossier & Hellen, 2014).

Evidence on the association of HIV status with fertility intentions and contraception is inconclusive. While several studies have argued that HIV positive women have lower fertility intentions and higher contraceptive use than their HIV negative counterparts (e.g., Bankole, Biddlecom, & Dzekedzeke, 2011; Hoffman et al., 2008; Marlow et al., 2015; Taulo et al., 2009), other research shows considerable variation in fertility intentions and contraceptive use of HIV positive individuals (Blanchard et al., 2011; MacQuarrie et al., 2014; Nattabi et al., 2009). The increasing availability of antiretroviral therapy (ART) may affect the relationship between HIV status and reproductive intentions and behaviour. As access to ART widens, especially during antenatal and postnatal periods, it may boost fertility intentions and increase pregnancy incidence among seropositive women (e.g., Cooper et al., 2009; Kaida et al., 2010; Maier et al., 2009; Makumbi et al., 2011; Myer et al., 2010; Smith & Mbakwem, 2007; Tweya et al., 2013).

Hypotheses

In this exploratory study, we examined postpartum initiation and subsequent use of modern contraception among HIV positive and negative women who gave birth in four clinics in rural southern Mozambique. Guided by the literature on the effects of the rapidly increasing penetration and routinization of antenatal and postnatal ART on fertility, we formulated and tested the following two hypotheses regarding the association of HIV status with postpartum contraceptive uptake and subsequent use and regarding the role of fertility intentions in shaping this association. Overall, given the strong encouragement that HIV positive women typically receive from health providers to use contraception, we hypothesized that seropositive women will start contraceptive use earlier after birth and will be more likely to use it in the long postpartum period, compared to seronegative women (Hypothesis 1). However, we also considered how the intention to stop childbearing may modify the association between HIV status and contraceptive use. We proposed that in the era of near-universal access to postpartum ART, HIV positive women will not differ from HIV negative ones in long-term fertility intentions because access to and experience of ART expand their perceived lifetime horizons. Yet, while increasingly resembling their negative peers in fertility expectations and plans, HIV positive women, encouraged by health providers, may see contraceptive use as a general health management strategy as well as a family planning tool. In contrast, for seronegative women contraception is a more straightforward instrument for achieving desired family size. Based on these propositions, we hypothesized that fertility intentions will affect the timing of postpartum contraceptive initiation and the likelihood of continuous use more strongly among HIV negative women than among their HIV positive counterparts (Hypothesis 2).

The setting

The data used in this study were collected in a district in Gaza Province in southern Mozambique in 2012–13. A former Portuguese colony that gained independence in 1975, Mozambique was mired in a devastating civil war for the first decade and a half of its independent existence. Since the end of the war in 1992 and the introduction of structural reforms in the early 1990s, Mozambique has generally experienced robust macroeconomic growth. Despite this growth, however, Mozambique remains one of the world’s poorest countries, with an annual GDP per capita of about USD 580 (World Bank, 2015). Mozambique is also among the world’s most affected countries by the HIV/AIDS epidemic, with the national HIV prevalence of 12–16% of the adult population, depending on the estimates. The province of Gaza, where data for this study were collected, has the highest estimated HIV infection rate in the country: 25–27% of adults aged 15–49 and as high as 30% among women of that age range (Ministry of Health, 2009; 2014).

Fertility in Mozambique has been persistently high: according to the three Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), the total fertility rate (TFR) was 5.6 in 1997, 5.5 in 2003, and 5.9 in 2011 (National Institute of Statistics, 2013, p. 75). In Gaza province, the DHS data suggest a slight decline of TFR: from 5.9, to 5.4 in 2003, to 5.3 in 2011 (National Institute of Statistics, 2013, p. 76). According to the 2011 Mozambique DHS, modern contraceptive prevalence among women in union aged 15–49 was only 11%, the same level registered in the previous DHS conducted eight years earlier (National Institute of Statistics, 2013, p. 71; National Institute of Statistics, 2005, p. 98). In Gaza, contraceptive prevalence has been slightly higher than the national average, 18%, but has also remained unchanged between the two last DHS (National Institute of Statistics, 2013, p. 72; National Institute of Statistics, 2005, p. 100). Prevalence of condom use, at 1%, was particularly low (National Institute of Statistics, 2005, p. 100). According to the 2011 DHS, 97% of mothers abstained from sex during the first two months after birth, with this percentage declining to 53% at 8–9 months after birth (National Institute of Statistics, 2013, p. 79).

The district where data for this study were collected is a typical land-locked, monoethnic, predominantly Christian district of Gaza province. The majority of its population of about 200,000 lives in rural areas and is engaged in low-yield subsistence agriculture. The precarious nature of local agricultural production and proximity to South Africa, Mozambique’s much more developed neighbour, has resulted in high rates of male labour migration to that country (de Vletter 2007). In addition, the area has also been a source of migrants to other parts of Mozambique, especially the nation’s capital city of Maputo.

At the time of data collection, there were 12 health clinics in the district that provided maternal and child health (MCH) and other medical services to the district’s population. All these facilities are part of the National Health Service (NHS) network and provide all MCH services, as well as HIV testing and ART, free of charge. The area has a relatively high coverage of institutional child deliveries—c.70% (Agadjanian, Yao, & Hayford, 2016); in addition, many of the women who happen to deliver outside a health clinic bring their newborns there for checkups and vaccinations early after the birth. The area has a very high coverage of antenatal care, with almost all pregnant women attending at least one antenatal consultation (Agadjanian, Yao, & Hayford, 2016). All pregnant women receiving antenatal and delivery care are routinely tested for HIV.

Family planning has been provided at all these facilities for many years following the standard Ministry of Health (MOH) guidelines. Initial family planning counselling is typically done at prenatal consultations and then at the first postpartum checkup between 3–7 days after delivery. However, method-specific counselling is typically offered starting only at 4–6 weeks after birth (usually timed with the administration of the polio vaccine to the child). Although HIV positive and HIV negative women are offered the same array of contraceptive options, the Ministry of Health guidelines stress dual protection (i.e., consistent condom use along with another contraceptive method of choice) particularly for the former (Ministry of Health, 2014, p. 77). Reliable statistics on postpartum ART utilization in the district are not available, but observations at local clinics and extensive interactions with health practitioners and administrators suggest a near universal availability and a rapidly growing coverage.

Data and Method

Data

The data come from a survey of women who gave birth in four rural maternity clinics (or brought their newborns there shortly after birth) in 2010–2011. The four clinics included in the study are located in different parts of the district and were purposively selected to represent a range of clinic and community settings. Three of the clinics are of comparable patient load, with 231, 268, and 284 births, respectively, in a twelve-month period. These births were used as a sampling frame in each of these clinics. The fourth clinic is located in a more densely populated area and had a much heavier patient flow. For that reason, in the fourth clinic we sampled births only over a six-month period (during which the clinic reported 403 births). The sampling strategy was guided by our goal to explore variations in contraceptive uptake and use by HIV status; the sample therefore was not meant to reflect HIV prevalence among reproductively active women in the study area. We aimed to sample 75 women from each clinic. Because this study was designed as an exploratory study, we set the target sample size based on the expected degree of heterogeneity in the sample (drawing on our previous research in the study area) and the field team’s capacity to track respondents, rather than on formal power calculations. In building each clinic’s sample, we first selected all HIV positive women who gave birth at that clinic during the reference time period. We then randomly selected HIV negative women from the list of seronegative parturients in each clinic to reach the target sample size. A reserve list of 15 randomly selected HIV negative women per clinic was constructed at the same time to supplement any women from the main list who could not be located.

In 2012–13, interviewers attempted to locate selected women using information available in the clinic delivery records (name, village of residence, and date of delivery). Women from the main list who could not be located were replaced by women from the reserve list. The final localization rate averaged 65% across clinics, being the lowest (47.5%) for the biggest clinic located in the community with the largest population size and highest residential density. All the located women consented to participating in the study and were interviewed using a standardized questionnaire. In all, the final sample consisted of 285 valid cases, including 121 HIV positive women and 164 HIV negative women.

The survey instrument contained detailed questions covering women’s socioeconomic background, marital and household characteristics, health of the focal child and of the respondent, and their interactions with the health care institution. A separate module of the instrument was focused on women’s knowledge and experience of family planning, including questions on family planning counselling received during and after the focal pregnancy, timing of use of specific contraceptive methods, side-effects if any, reasons for discontinuation, etc. Importantly, to minimize interviewer biased, the survey content was HIV-neutral and interviewers did not know the HIV status of respondents. In addition to the survey of women, attempts were made to interview marital partners of those who were in marital partnership about the partners’ knowledge of and attitudes toward family planning use. However, mainly because of high levels of male labour mobility, only forty-two partner interviews were completed. The partner interview data are not used in this analysis because of their small and highly biased sample. Data collection was carried out in collaboration between Arizona State University (USA), Eduardo Mondlane University (Mozambique), and Women’s Forum (Mozambique). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Arizona State University and the Ethics Board of the Ministry of Health (Mozambique).

Method

We first described modern contraceptive use and the timing of contraceptive uptake, (regardless of specific method) comparing women who were HIV positive at the time of the focal birth and those who were not. Survival to contraception initiation after the focal birth for the two groups of women was modelled according to their intention to stop childbearing. The intention to stop childbearing was operationalized as a dichotomy: women who did not want to have any more children were contrasted with women who wanted to have at least one additional child in the future or were not sure about their childbearing plans.

For multivariate analyses, a set of two proportional hazards (Cox) models were first fitted to predict the hazard of contraceptive initiation. The exposure to risk of first contraceptive use was measured in months since the focal birth and was censored at the time of new pregnancy or at the time of the survey interview if no pregnancy occurs before that. Then, two logistic regression models were fitted to predict modern contraceptive use at the time of the survey. In both Cox and logistic regression models, the predictors of interest were respondent’s HIV status at the time of focal delivery and her intention to stop childbearing. We used fertility intentions stated at the time of survey for both the contraception initiation model and the current use model.

Although fertility intentions can change in response to changes in women’s circumstances and constraints, intentions to stop childbearing are likely to be relatively stable over the short term, especially in this sample of women who are, on average, in the middle of their reproductive span. The first model for each outcome of interest tested Hypothesis 1 and included only main effects. To test our hypothesis about moderating effects of fertility intentions on contraceptive uptake and use (Hypothesis 2), the second model in each set added interactions between HIV status and the intention to stop childbearing.

All the models included several characteristics of respondents and their households: age, number of children prior to focal birth, partnership status, education, church attendance, housing quality, and mobile phone ownership. The models also controlled for distance to clinic and antenatal family planning counselling, as well as for survival of the focal child. Both the Cox and logistic regression models were fitted using SAS, version 9, stratifying the analysis by clinic.

Results

Descriptive results

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the sample. Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for the variables of interest for the entire sample and by HIV status. Although fully three-quarters of respondents reported having received family planning counselling at a prenatal consultation or shortly after delivery (Table 1), only 41.4% of them said that they had used a modern contraceptive method, typically the hormonal pills or injectables, at least once since the focal birth. The share of ever-users was nearly the same among HIV positive and HIV negative women. Ever-users started using contraception on average at 7.1 months after the childbirth, again with no difference by HIV status.1 A third (33.7%) of non-pregnant women reported using a contraceptive method at the time of survey, with the percentage of current users among HIV positive women being somewhat higher than among HIV negative ones.2 Finally, 51.9% of the respondents stated that they did not want to have any more children in the future, with this share being somewhat higher among HIV negative women.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (percent unless otherwise noted)

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| HIV positive | 42.5 |

| Time since birth of focal child (months, mean) | 22.3 |

| Age (mean) | 29.5 |

| Number of children ever born (mean) | 3.6 |

| Focal child died | 17.2 |

| Became pregnant after focal child’s birth | 13.3 |

| Marital partnership | |

| No current partner | 30.5 |

| Partner currently stays in same village | 22.5 |

| Partner currently stays outside village | 47.0 |

| Education | |

| Never went to school | 31.2 |

| Completed between 1 and 5 years of school | 39.2 |

| Completed 6 or more years of school | 29.5 |

| Material conditions | |

| Residence roof made of zinc sheets or similar | 55.8 |

| Has a mobile phone | 48.8 |

| Went to a church at least once in past two weeks | 66.0 |

| Distance from residence to clinic of focal birth | |

| Less than 3km | 39.0 |

| 3–7km | 44.9 |

| 8km or more | 16.1 |

| Received antenatal family planning counselling | 75.1 |

| Number of observations | 285 |

Table 2.

Modern contraceptive use and intention to stop childbearing (percent)

| Characteristic | All | HIV+ | HIV− |

|---|---|---|---|

| Used a modern contraceptive method at least once since focal birth | 41.4 | 41.3 | 41.5 |

| Time to first modern contraceptive use since focal birth (months, mean) | 7.1 | 7.2 | 7.1 |

| Was using a modern contraceptive method at time of surveya | 33.7 | 37.2 | 31.1 |

| Wants no more children | 51.9 | 50.4 | 53.1 |

Note:

non-pregnant women only.

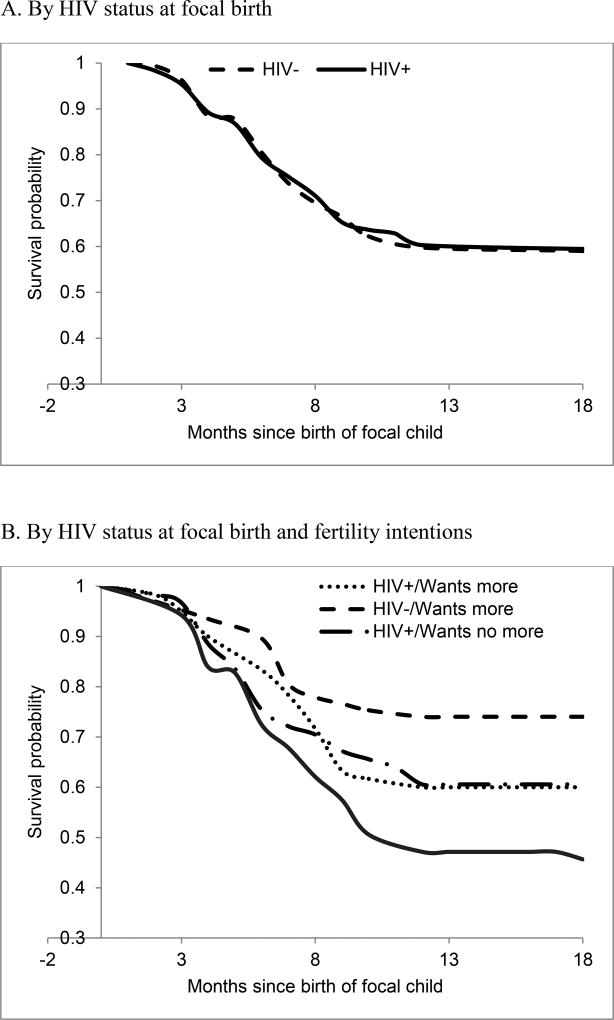

Figure 1A displays Kaplan-Meier estimates of contraceptive initiation for women who were HIV positive and those who were HIV negative at the time of focal birth. Echoing the patterns displayed in Table 2, the timing of contraceptive initiation is almost identical for the two groups: among both HIV positive and negative women, contraceptive use starts relatively early and most contraceptive uptake occurs within ten months of birth, with the mean time to first contraceptive use almost identical among the two categories of women (7.1 and 7.2 months among HIV positive and HIV negative women, respectively). In fact, women who do not start using contraception before the end of the first year after birth are very unlikely to use contraception at all.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of contraceptive initiation (survival to first contraceptive use since focal birth, in months)

Figure 1B subdivides each HIV status group into two subgroups: those who wanted to stop childbearing (50.4% and 53.1% of HIV positive and HIV negative respondents, respectively) and those who wanted to have another child or were not sure about their reproductive intentions (49.6% and 46.9%). It shows a considerable gap between the two subgroups of HIV negative women: as one would expect, women who did not want to have any more children were more likely to start contraception earlier than women who wanted to continue childbearing or were undecided. However, this pattern is absent among HIV positive women: their contraceptive uptake does not seem to be affected by fertility intentions.

Multivariate results

The results of a multivariate proportional hazard (Cox) event-history model predicting the hazard of contraceptive initiation are displayed in Table 3, Section 1A, as parameter estimates and corresponding standard errors. Paralleling the bivariate results presented earlier, the effect of HIV status is very small in magnitude and not statistically significant. Model 1B adds the HIV status-fertility intentions interaction term. In this model, the coefficients for both the main effects of the two variables and for the interaction term are significantly different from zero. As these results show, being infected with HIV significantly increases the hazard of contraceptive initiation for women who want to have another child or are unsure about their future reproductive plans (β =0.64). The main effect of not wanting another child, which now represents HIV negative women, is large in magnitude and highly significant (β=1.18; p<0.01), echoing the pattern displayed in Figure 1B. However, the interaction between being seropositive and wishing to stop childbearing is negative, statistically significant, and relatively large in magnitude (β= −1.28). That is, among seropositive women the net association of wanting no more children with contraceptive use is close to zero (1.18 + (−1.28)).

Table 3.

Proportional hazards models of contraceptive initiation (Models 1A and 1B) and logistic regression models of current contraceptive use (Models 2A and 2B), parameter estimates and standard errors.

| 1. Contraceptive initiation | 2. Current contraceptive use | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1A | 1B | 2A | 2B | |||||

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |

| HIV status at time of focal birth | ||||||||

| HIV positive | −0.09 | 0.20 | 0.64 | 0.31* | 0.19 | 0.30 | 1.23 | 0.48* |

| [HIV negative] | ||||||||

| Fertility intentions | ||||||||

| Wants no more children | 0.58 | 0.22* | 1.18 | 0.30** | 1.12 | 0.34** | 1.99 | 0.47** |

| [Wants more children or unsure] | ||||||||

| Interaction: HIV positive × Wants no more | −1.28 | 0.41** | −1.82 | 0.64** | ||||

| Demographic & health characteristics | ||||||||

| Age | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.04** | 0.10 | 0.04** |

| Parity | −0.11 | 0.08 | −0.11 | 0.08 | −0.23 | 0.12 | −0.22 | 0.12 |

| Has a partnera | 0.02 | 0.24 | 0.01 | 0.23 | ||||

| Has a partner who stays in the village | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | −0.39 | 0.44 | −0.47 | 0.44 |

| Has a partner who stays outside the village | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | −0.29 | 0.38 | −0.30 | 0.38 |

| [Does not have a partner] | ||||||||

| [No education] | ||||||||

| Completed 1–5 years | 0.14 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 0.28 | 0.63 | 0.40 | 0.73 | 0.41 |

| Completed 6 or more years | 0.67 | 0.31* | 0.71 | 0.31* | 1.29 | 0.47** | 1.37 | 0.47** |

| Focal child dieda | −0.68 | 0.35 | −0.79 | 0.35* | −0.58 | 0.43 | −0.64 | 0.44 |

| [Focal child did not die] | ||||||||

| Household & social characteristics | ||||||||

| Residence roof made of zinc sheets or similar | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.34 |

| [Roof made of reed or grass] | ||||||||

| Has a mobile phone | 0.37 | 0.22 | 0.38 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.32 | 0.22 | 0.33 |

| [Does not have a mobile phone] | ||||||||

| Went to church in past 2 weeks | 0.47 | 0.25 | 0.48 | 0.25 | 0.99 | 0.36** | 1.03 | 0.36** |

| [Did not go to church in past 2 weeks] | ||||||||

| Clinic access & and experience | ||||||||

| Distance from residence to clinic | ||||||||

| [Less than 3km] | ||||||||

| 3–7km | −0.02 | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.21 | −0.10 | 0.32 | −0.00 | 0.33 |

| 8km or more | −0.61 | 0.35 | −0.61 | 0.35 | −0.55 | 0.50 | −0.59 | 0.51 |

| Received antenatal FP counseling | 0.77 | 0.29** | 0.76 | 0.29** | 1.31 | 0.46** | 1.35 | 0.47** |

| [Received no antenatal FP counseling] | ||||||||

| −2Log Likelihood | 630 | 621 | 270 | 261 | ||||

| Number of observations | 285 | 285 | 283 | 283 | ||||

Notes: Reference categories in brackets;

time-varying covariates in Cox regression;

Significance levels: *p< .05,

p< .01.

Sections 2A and 2B of Table 3 display the results of two logistic regression models predicting the probability of contraceptive use at the time of survey from the same set of covariates. The results are similar to those of the event history analysis, suggesting that the factors associated with contraceptive uptake also predict continuation of use. While the main effects-only model shows no statistically significant difference between HIV positive and negative women, in the model with the interaction term (2B), the main effect of being HIV positive, β =1.23, which now represents HIV positive women wishing to have more children or those unsure about their reproductive plans, is positive and statistically significant, corresponding to 3.42 times higher odds of using a contraceptive method compared HIV negative women with similar fertility intentions (OR=exp(1.23)=3.42). In this model, the main effect of wanting no more children, now representing HIV negative women wishing to stop childbearing, is also positive, large, and statistically significant, with β=1.99 and the corresponding odds ratio of 7.30. The interaction term is significant and negative, β= −1.82. As in the previous model, the net effect of wanting to stop childbearing is close to zero among HIV positive women (1.99 + (−1.82)).

Among other covariates, age and number of children show no significant associations with the hazard of contraceptive initiation; nor are they significantly related to the likelihood of current contraceptive use. Partnership status is not significant in either pair of models. In comparison, the effect of respondent’s education is positive; notably, however, only the contrast between the lowest and highest educational levels is statistically significant at p<0.05. Household material conditions, represented by the type of roof and mobile phone ownership, show no effect on either outcome. Interestingly, women who attended church were significantly more likely to be using contraceptives than women who did not, echoing the finding of an earlier study in this part of Mozambique (Agadjanian, 2013). Having received family planning advice in the antenatal and perinatal periods is associated with both earlier contraceptive initiation and higher likelihood of current use. The effect of distance to clinic of delivery on both contraceptive initiation and current use is also in the expected direction, but it is not statistically significant at the conventional threshold.

Discussion and Conclusion

The foregoing analysis produced an instructive picture of postpartum contraception in this rural sample. Overall, reported contraceptive use – overwhelmingly oral or injectable hormonal methods – did not vary by HIV status and was relatively high compared to the DHS estimate for Gaza Province. Most users reported having initiated contraception within the first ten months of birth. Interestingly, much contraceptive use starts during postpartum abstinence and before the resumption of menstruation after childbirth. This pattern contradicts the widely held assumption that postpartum amenorrhea and abstinence are barriers to contraceptive uptake in sub-Saharan settings and requires further investigation. At the same time, the very low reported use of condoms, regardless of HIV status, which conforms to DHS data (National Institute of Statistics, 2013, p.100) and parallels evidence from some other resource-limited sub-Saharan settings (e.g., Ngure et al., 2012; Peltzer, Chao, & Dana, 2009), is a reason for concern, especially in light of the MOH continuous efforts to promote condom use for HIV prevention among HIV negative couples and as part of dual protection among HIV-affected couples.

Contrary to Hypothesis 1, there were no overall differences between HIV positive and negative women in timing of contraceptive initiation or in likelihood of using contraception. However, the results did point to a moderating effect of reproductive intentions on the association between HIV status and contraceptive uptake and use, thus lending support to Hypothesis 2. These results suggest that contraception is an important instrument for pursuing reproductive goals among seronegative women who want to end childbearing. However, fertility intentions are not related to contraceptive initiation or use among seropositive women, who use contraception at similar levels regardless of whether they want to have another child in the future. Interestingly, both the risk of contraceptive initiation and the probability of continuing use among HIV positive women are somewhere in between the corresponding values for HIV negative women who wished to stop childbearing and HIV negative women who desired another child or were unsure about future reproductive plans.

Our tentative interpretation of these results builds upon the “now-or-never” approach to HIV and fertility proposed by Hayford, Agadjanian, and Luz (2012). In that study, the authors argued that HIV positive women were more likely both to speed up childbearing and to end it altogether, compared to negative women; these seemingly contradictory tendencies reflected the widespread belief that childbearing is incompatible with HIV in the long run. We propose that these contradictory attitudes have gradually evolved as the increasing coverage and routinization of postpartum ART has expanded the life horizons of HIV positive individuals and transformed HIV from a stigmatized death sentence to a serious yet clinically and socially manageable health condition. This evolution diminishes differences in fertility intentions between HIV positive and negative women, and, in turn, affects the patterns of contraceptive initiation and use among the former. Thus, those HIV positive women who want to have another child may not feel an urgency to become pregnant early as they no longer expect their health to deteriorate quickly. With active encouragement from health providers and probably with support from their partners and significant others, these women may increasingly choose contraception as part of management of their HIV infection by waiting for the “right” time to get pregnant. A direct test of these explanations would require more detailed measures of fertility intentions, including measures of desired timing of birth, as well as detailed data on women’s interactions with providers, partners, and others. At the same time, the rate of contraceptive initiation and the likelihood of current use among seropositive women who wanted to stop childbearing were lower than among seronegative women with similar intentions. It is possible that the nature and strength of the stopping intention differ between HIV positive and negative women, but this proposition also needs further study with more specialized data.

Limitations of our exploratory study must be acknowledged. Our analysis relies on self-reported contraceptive use, and as in any such study, reporting bias and accuracies may exist, especially with given the retrospective nature of the questions. The analysis is based on a relatively small sample from only four rural clinics. In order to maximize statistical power for the comparison of HIV positive and HIV negative women, HIV positive women were oversampled. Still, the sample may be underpowered for the detection of small-size effects, and thus caution must be exercised in interpreting weak statistical associations. HIV status is available only for the time of the focal child delivery. To minimize the interviewer bias and potential for misreporting, the survey instrument was HIV-neutral and did not include questions on ART. In this setting of high male labour mobility and increasing marital instability only a small and probably non-representative fraction of male partners could be interviewed and therefore the input of men into reproductive and contraceptive decisions could not be accounted for. While some covariates in the event-history model are time-varying others could only be measured at the time of survey.

These limitations notwithstanding, our findings illustrate both the change and continuity of reproductive behaviour in the era of widespread access to ART. While rapidly increasing availability of ART greatly diminishes the differences in fertility between HIV positive and HIV negative women observed in earlier stages of the HIV/AIDS pandemic by increasing desires for additional children and pregnancy incidence among seropositive women, it does not completely eliminate doubts and concerns surrounding both short- and longer-term implications of the HIV status for both mother’s and child’s health and wellbeing (O’Shea et al., 2016). Nor does it fully equip women and couples to deal with social and cultural pressures surrounding marriage, sex, and childbearing (Smith & Mbakwem, 2007). These uncertainties often result in inconsistent contraceptive use and lead to unplanned pregnancies (Laryea et al., 2014; Schwartz et al., 2012; Schaan, Taylor, & Marlink, 2014). Although our study focuses on only one high-prevalence sub-Saharan setting and cannot be readily generalized to the rest of the sub-continent, the results of the analysis propose an interesting and important avenue for further examination of reproductive and contraceptive itineraries in other rural sub-Saharan settings with high HIV prevalence and widening access to ART.

Acknowledgments

Data collection for this study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development under grant # R01HD058365.

Footnotes

Notably, the median reported period of postpartum abstinence was about six months, and 15% of women in the sample reported not having sex for at least one year after the pregnancy. The median duration of postpartum amenorrhea was even longer, at nine months. Along with the data on timing of first postpartum contraceptive use, these figures suggest that postpartum abstinence and amenorrhea do not necessarily deter use of contraception. In fact, substantial proportions of eventual users began use before resuming sex (31%) or before having a first post-partum menstruation (47%) (these statistics are not shown in Table 2 but are available from the authors upon request).

Only four respondents reported ever trying a male condom since the birth of the focal child and only two respondents were using condoms at the time of survey. It is possible that condom use was underreported in the survey, although our field observations and interviews with providers suggest that despite the vigorous promotion of condoms by health authorities, condom use in stable partnerships remains infrequent and sporadic.

References

- Andia I, Kaida A, Maier M, Guzman D, Emenyonu N, Pepper L, Hogg RS. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and increased use of contraceptives among HIV-positive women during expanding access to antiretroviral therapy in Mbarara, Uganda. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(2):340–347. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.129528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agadjanian V. Religious denomination, religious involvement and contraceptive use in Mozambique. Studies in Family Planning. 2013;44(3):259–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2013.00357.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agadjanian V, Yao J, Hayford SR. Place, time, and experience: Barriers to universalization of institutional child delivery in rural Mozambique. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2016;42(1):21–31. doi: 10.1363/42e0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankole A, Biddlecom AE, Dzekedzeke K. Women's and men's fertility preferences and contraceptive behaviors by HIV status in 10 sub-Saharan African countries. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2011;23(4):313–328. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.4.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard K, Holt K, Bostrom A, van der Straten A, Ramjee G, de Bruyn G, Chipato T, Montgomery ET, Padian NS. Impact of learning HIV status on contraceptive use in the MIRA trial. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care. 2011;37(4):204–208. doi: 10.1136/jfprhc-2011-0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland J, Harbison S, Shah IH. Unmet need for contraception: issues and challenges. Studies in Family Planning. 2014;45(2):105–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland J, Shah IH, Daniele M. Interventions to improve postpartum family planning in low- and middle-income countries: Program implications and research priorities. Studies in Family Planning. 2015;46(4):423–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2015.00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper D, Moodley J, Zweigenthal V, Bekker LG, Shah I, Myer L. Fertility intentions and reproductive health care needs of people living with HIV in Cape Town, South Africa: implications for integrating reproductive health and HIV care services. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(1):38–46. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9550-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darroch JE, Singh S. Trends in contraceptive need and use in developing countries in 2003, 2008, and 2012: An analysis of national surveys. The Lancet. 2013;381(9879):1756–1762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60597-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vletter F. Migration and development in Mozambique: poverty, inequality and survival. Development Southern Africa. 2007;24(1):137–153. doi: 10.1080/03768350601165975. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Engin-Üstün Y, Üstün Y, Çetin F, Meydanlı MM, Kafkaslh A, Sezgin B. Effect of postpartum counseling on postpartum contraceptive use. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2007;275(6):429–432. doi: 10.1007/s00404-006-0287-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazer AB, Wolf A, Gorby N. Postpartum contraception: needs vs. reality. Contraception. 2011;83(3):238–241. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habte D, Namasasu J. Family planning use among women living with HIV: knowing HIV positive status helps-results from a national survey. Reproductive Health. 2015;12(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s12978-015-0035-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayford SR, Agadjanian V, Luz L. Now or never: perceived HIV status and fertility intentions in rural Mozambique. Studies in Family Planning. 2012;43(3):191–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2012.00317.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman IF, Martinson FE, Powers KA, Chilongozi DA, Msiska ED, Kachipapa EI, Tsui AO. The year-long effect of HIV-positive test results on pregnancy intentions, contraceptive use, and pregnancy incidence among Malawian women. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2008;47(4):477–483. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318165dc52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaida A, Laher F, Strathdee SA, Money D, Janssen PA, Hogg RS, Gray G. Contraceptive use and method preference among women in Soweto, South Africa: the influence of expanding access to HIV care and treatment services. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(11):1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastner J, Matthews LT, Flavia NT, Bajunirwe F, Erickson S, et al. Antiretroviral therapy helps HIV-positive women navigate social expectations for and clinical recommendations against childbearing in Uganda". AIDS Research and Treatment. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/626120. Article ID 626120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S, Mishra V, Arnold F, Abderrahim N. Contraceptive trends in developing countries. [November 30, 2016];Calverton, MD. Macro International Inc. DHS Comparative Reports No. 16. 2007 Retrieved from http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/CR16/CR16.pdf on.

- Laryea DO, Amoako YA, Spangenberg K, Frimpong E, Kyei-Ansong J. Contraceptive use and unmet need for family planning among HIV positive women on antiretroviral therapy in Kumasi, Ghana. BMC Women’s Health. 2014;14:126. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-14-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacQuarrie K, Bradley S, Gemmill A, Staveteig S. DHS Analytical Studies No. 47. Rockville, Maryland, USA: ICF International; 2014. Contraceptive Dynamics Following HIV Testing. [Google Scholar]

- Maier M, Andia I, Emenyonu N, Guzman D, Kaida A, Pepper L, Bangsberg DR. Antiretroviral therapy is associated with increased fertility desire, but not pregnancy or live birth, among HIV+ women in an early HIV treatment program in rural Uganda. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(1):28–37. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9371-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makumbi FE, Nakigozi G, Reynolds SJ, Ndyanabo A, Lutalo T, Serwada D, Gray R. Associations between HIV antiretroviral therapy and the prevalence and incidence of pregnancy in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS Research and Treatment. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/519492. Article ID 519492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlow, et al. HIV status and post-partum contraceptive use in an antenatal population in Durban, South Africa. Contraception. 2015;91(1):39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy SI, Buzdugan R, Ralph LJ, Mushavi A, Mahomva A, Hakobyan A, Padian NS. Unmet need for family planning, contraceptive failure, and unintended pregnancy among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women in Zimbabwe. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8):e105320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health of Mozambique. Report on the revisions of the HIV epidemiological surveillance data from the 2007 round. (in Portuguese) Maputo, Mozambique: Ministry of Health; 2008. Relatório sobre a revisão dos dados de vigilância epidemiológica do HIV – Ronda 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health of Mozambique. National Survey of HIV/AIDS prevalence, behavioral risks, and information (INSIDA), 2009. Maputo, Mozambique: Ministry of Health; 2010. Inquérito nacional de prevalência, riscos comportamentais e informação sobre o HIV e SIDA (INSIDA) 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health of Mozambique. Guidelines for antiretroviral treatment and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults, adolescents, pregnant women, and children. Maputo, Mozambique: Ministry of Health; 2014. Guia de tratamento antiretroviral e infecções oportunistas no adulto, adolescente, grávida e criança. [Google Scholar]

- Myer L, Carter RJ, Katyal M, Toro P, El-Sadr WM, Abrams EJ. Impact of antiretroviral therapy on incidence of pregnancy among HIV-infected women in Sub-Saharan Africa: a cohort study. PLoS Medicine. 2010;7(2):1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Statistics. Demographic and Health Survey 2003, Final Report. Maputo, Mozambique: National Institute of Statistics; 2005. Moçambique: Inquérito Demográfico e de Saúde 2003, Relatório Final. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Statistics. Demographic and Health Survey 2011, Final Report. Maputo, Mozambique: National Institute of Statistics; 2013. Moçambique: Inquérito Demográfico e de Saúde 2011, Relatório Final. [Google Scholar]

- Nattabi B, Li J, Thompson SC, Orach CG, Earnest J. A systematic review of factors influencing fertility desires and intentions among people living with HIV/AIDS: implications for policy and service delivery. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(5):949–968. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9537-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngure K, Mugo N, Celum C, Baeten JM, Morris M, Olungah O, Olenja J, Tamooh H, Shell-Duncan B. A qualitative study of barriers to consistent condom use among HIV-1 serodiscordant couples in Kenya. AIDS Care. 2012;24(4):509–516. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.613911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea MS, Rosenberg NE, Tang JH, Mukuzunga K, Kaliti S, Mwale M, Hosseinipoor MC. Reproductive intentions and family planning practices of pregnant HIV-infected Malawian women on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Care. 2016;28(8):1027–1034. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1140891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K, Chao LW, Dana P. Family planning among HIV positive and negative prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) clients in a resource poor setting in South Africa. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(5):973–979. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9365-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petruney T, Robinson E, Reynolds H, Wilcher R, Cates W. Contraception is the best kept secret for prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2008;86(6) doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.051458. B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds HW, Steiner MJ, Cates W. Contraception’s proved potential to fight HIV. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2005;81(2):184–185. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.012013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossier C, Hellen J. Traditional birthspacing practices and uptake of family planning during the postpartum period in Ouagadougou: qualitative results. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2014;40(2):87–94. doi: 10.1363/4008714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SR, Rees H, Mehta S, Venter WDF, Taha TE, et al. High incidence of unplanned pregnancy after antiretroviral therapy initiation: Findings from a prospective cohort study in South Africa. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4):e36039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaan MM, Taylor M, Marlink R. Reproductive behaviour among women on antiretroviral therapy in Botswana: mismatched pregnancy plans and contraceptive use. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2014;13(3):305–311. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2014.952654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedgh G, Hussain R, Bankole A, Singh S. Women with an Unmet Need for Contraception in Developing Countries and Their Reasons for not using a Method. Alan Guttmacher Institute; New York: 2007. 2007 [Occasional Report No. 37] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Sedgh G, Hussain R. Unintended pregnancy: worldwide levels, trends, and outcomes. Studies in Family Planning. 2010;41(4):241–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DJ, Mbakwem BC. Life projects and therapeutic itineraries: marriage, fertility, and antiretroviral therapy in Nigeria. AIDS. 2007;21:S37–S41. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000298101.56614.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KB, Van der Spuy ZM, Cheng L, Elton R, Glasier AF. Is postpartum contraceptive advice given antenatally of value? Contraception. 2002;65(3):237–243. doi: 10.1016/S0010-7824(01)00308-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taulo F, Berry M, Tsui A, Makanani B, Kafulafula G, Li Q, Taha TE. Fertility intentions of HIV-1 infected and uninfected women in Malawi: a longitudinal study. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(1):20–27. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9547-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tweya H, Feldacker C, Breeze E, Jahn A, Haddad LB, Ben-Smith A, Phiri S. Incidence of pregnancy among women accessing antiretroviral therapy in urban Malawi: a retrospective cohort study. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(2):471–478. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcher R, Cates W, Jr, Gregson S. Family planning and HIV: strange bedfellows no longer. AIDS (London, England) 2009;23(Suppl. 1):S1–6. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000363772.45635.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winfrey W, Rakesh K. DHS Comparative Report. 36. Rockville, Maryland, USA: ICF International; 2014. Use of Family Planning in the Postpartum Period. [Google Scholar]

- [The] World Bank. World Bank Development Indicators. Mozambique. World Bank Publications; 2015. [November 30, 2016]. Retrieved from www.worldbank.org on. [Google Scholar]