Abstract

Background

Linear scleroderma "en coup de sabre" (LSCS) usually affects one side of the face and head in the frontoparietal area with band-like indurated skin lesions. The disease may be associated with facial hemiatrophy. Various ophthalmological and neurological abnormalities have been observed in patients with LSCS. We describe an unusual case of LSC.

Case presentation

A 23 year old woman presented bilateral LSCS and facial atrophy. The patient had epileptic seizures as well as oculomotor and facial nerve palsy on the left side which also had pronounced skin involvement. Clinical features of different stages of the disease are presented.

Conclusions

The findings of the presented patient with bilateral LSCS and facial atrophy provide further evidence for a neurological etiology of the disease and may also indicate that classic progressive facial hemiatrophy (Parry-Romberg syndrome) and LSCS actually represent different spectra of the same disease.

Background

Linear scleroderma "en coup de sabre" (LSCS) is a subtype of localized scleroderma (Tab. 1). LSCS, usually developing in the first or second decade of life, presents as band-like sclerotic lesions with more or less marked skin discoloration of the frontoparietal area. Characteristically, LSCS manifests unilaterally and does not extend below the eyebrow. The active stage usually lasts two to five years. Involutionary atrophy of skin, muscle, and even bone may occur. Neurological and ophthalmological abnormalities are not infrequent in LSCS [1-3]. We present an uncommon case of bilateral LSCS with facial atrophy and several neurological complications.

Table 1.

Variants of localized scleroderma recently classified by Tuffanelli [2]

| I. Localized scleroderma |

| a) Morphea [plaque-type; guttate; profound; nodular; bullous; Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini] |

| b) Linear scleroderma ["en coup de sabre"; with facial atrophy (Parry-Romberg syndrome); acral; with arthritis, myositis, and growth defects of bone; melorheostotic] |

| c) Generalized morphea [pansclerotic; edematous; with lichen sclerosus] |

| II. Localized scleroderma as a component of an overlap syndrome |

| a) Mixed connective tissue disease |

| b) Undifferentiated connective tissue disease |

| c) Sclerodermatomyositis |

| III. Localized scleroderma as a component of eosinophilic fasciitis (Shulman's syndrome) |

Case presentation

A 23-year-old woman presented with band-like sclerotic lesions and cicatricial alopecia on the left frontoparietal area (upper trigeminal dermatome). In this area, there was remarkable atrophy of skin and underlying tissues. She had complete ptosis of the left eye. Veins was clearly seen through the atrophic skin in the left temporal region. There was also a remarkable subcutaneous cleft above the right eyebrow and a nearly complete loss of the left eyebrow (Figs 1,2,3,4,5). The tongue or gums were not involved. The patient refused a skin biopsy from the frontal area. Onset of the disease was reported to have been at age 7, with a small scleroderma-like lesion on the left forehead. The lesion was asymptomatic and not preceded by trauma. Over the succeeding years, the sclerotic changes and atrophy gradually spread over the almost complete left frontoparietal area. The lesions did not respond to various treatment protocols including penicillin G and topical hydrocortisone. At the age of 16, a transcranial orbitotomy and frontal advancement was performed on the left side of the face. Because of her history of two grand-mal seizures, which had occurred during the last two years, she had anticonvulsant therapy with carbamazepine 600 mg daily. There was no family history for scleroderma or hemiatrophies.

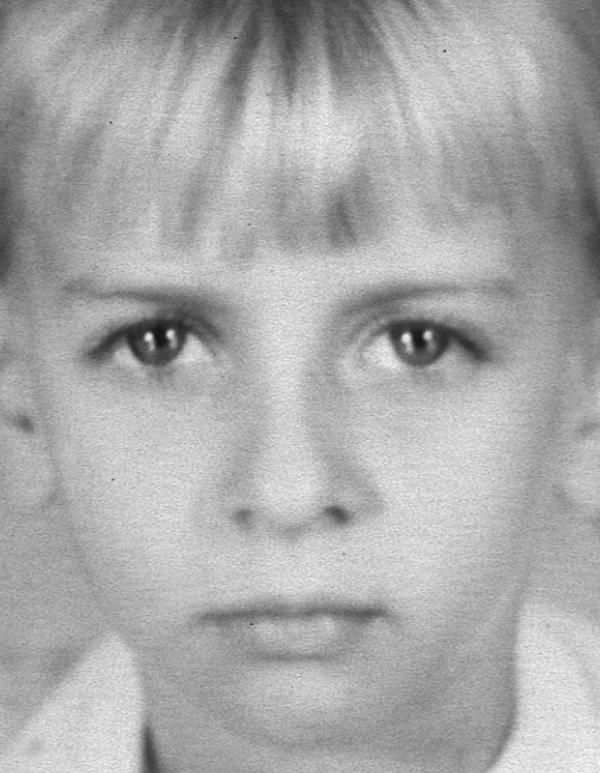

Figure 1.

The 7-year-old girl without recognizable features of LSCS.

Figure 2.

The 11-year-old girl with discrete facial palsy and mild facial atrophy of the left frontoparietal area.

Figure 3.

The 16-year-old girl with facial palsy, complete ptosis, and marked atrophy of subcutaneous and bony structures on the left upper side of the face before surgical intervention. Note the slight cleft above the right eyebrow and rarefication of the left eyebrow.

Figure 4.

The 23-year-old woman with facial palsy, complete ptosis, and improvement of facial asymmetry (as compared to Figure 3). Note the deep subcutaneous cleft above the right eyebrow and almost complete loss of the left eyebrow.

Figure 5.

The 23-year-old woman with LSCS and cicatricial alopecia on the left parietal region.

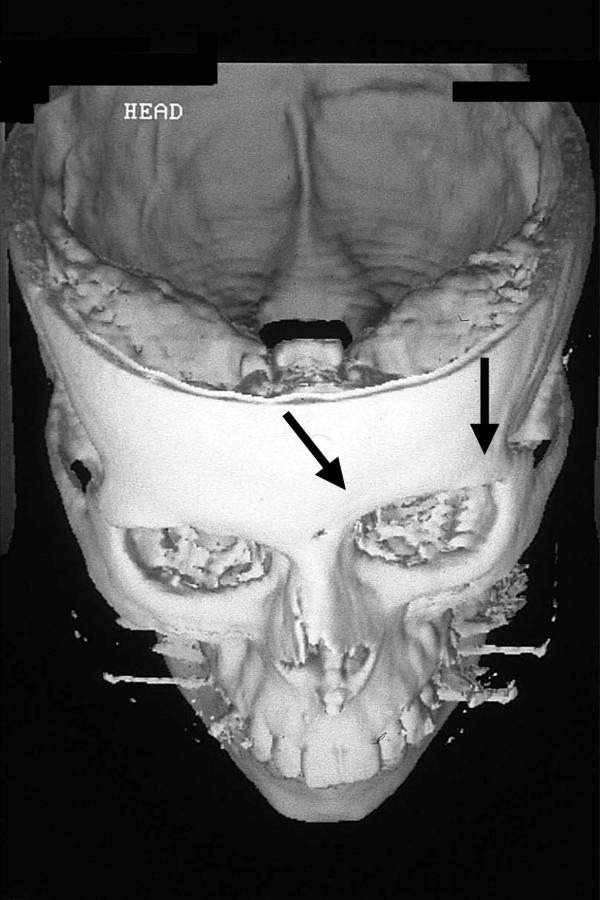

Neurological examination showed peripheral facial nerve palsy on the left side. Complete oculomotor nerve palsy of the left eye was confirmed by ophthalmological investigation. Laboratory investigations, including antinuclear antibodies and serology for B. burgdorferi, electrocardiography, abdominal sonography, and chest X-ray, did not yield abnormalities. Cranial magnetic resonance imaging (sagittal T1, axial T2, FLAIR before and after contrast medium injection) showed no pathological intracranial findings. Since the patient was intended for bony reconstruction surgery, 3-dimensional reconstruction images were performed using a spiral computed tomography scanner (Somatom Plus S, Siemens, Iselin, USA). Contiguous 2 mm axial slices of the facial skull were taken at 2 mm intervals. Oblique coronal, oblique sagittal, and 3-dimensional images were subsequently reconstructed from the data. Hypoplasia of facial bones on the left side were demostrated, in particular involvement of the frontal bone, orbital floor, and maxillary sinus (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

3-dimensional reconstruction image of the 16-year-old girl before urgical intervention. Remarkable hypoplasia of the frontal bone on the left side (arrows).

Discussion

In the present case, band-like scleroderma and facial atrophy of the frontoparietal area was observed. The skin involvement did not extend below the forehead. These features were consistent with a diagnosis of LSCS with facial atrophy [1-3]. In classic progressive facial hemiatrophy or Parry-Romberg syndrome (PRS), cutaneous inflammation, induration, and adhesion are absent or minimal, and atrophy usually involves the one entire side of the face [4-6]. It has been suggested that the term PRS should only be used for progressive hemifacial atrophy occurring without features of scleroderma [2]. However, a clear differentiation between PRS and involutionary LSCS is often not possible, and it is rather an arbitrary approach to differentiate the two diseases because of their extend on the face and more or less sclerosis, despite of all their common features observed. Although preceding sclerosis was never noticed in many cases of PRS, Jablonska and Blaszczyk [1] observed several patients with typical LSCS in children converting within several years into facial hemiatrophy. Thus the time of investigation is of significance when diagnosing either LSCS or PRS. There are no reliable histological criteria to differentiate PRS from involutionary scleroderma. Recently, Blaszczyk et al. [7] reported three cases of primary atrophic profound linear scleroderma with involvement of the subcutis and deeper tissues. In accordance with a previous report of Malandrini et al. [8], deep skin biopsies showed inflammatory infiltrates in the endomysium and perimysium. Interestingly, atrophy was not preceded by clinical evidence of inflammation, discoloration of the skin, or sclerosis. Blaszczyk et al. [7] concluded that PRS could be regarded as a variety of deep linear scleroderma [7,9].

Common theories on the etiology of LSCS are: firstly, that the localized forms of scleroderma are related in the same manner as discoid and systemic lupus erythematosus and thus belonging in the collagen-vascular group of diseases with autoimmune phenomena or secondly, that localized scleroderma is a developmental disease, occasionally associated with other (predetermined) defects [2]. Other theories implicate that viral or bacterial infections (e.g. B. burgdorferi) and genetic factors may play a role in the etiology of LSCS [1]. However, a multifactorial pathogenesis of hemiatrophies is most likely. Ophthalmological (e.g. iridocyclitis, enophthalmus, exophthalmus) and/or neurological (e.g. intracerebral calcification, hemiplegic headaches, epileptic seizures) manifestations have frequently been observed in patients with LSCS and PRS [2-4,10,11]. Besides, non-neurogenic myopathy associated with LSCS has previously been reported [11,12]. However, cranial nerve palsy coexisting with LSCS or PRS is a rarity. The involved areas in LSCS do usually not cross the midline and may resemble innervated fields in a cranial nerve distribution, in particular the upper trigeminal dermatome, raising the possibility of a neurogenic origin. It has therefore been suggested that LSCS and PRS result from hyper- or hypoactivity of sympathetic nervous system or abnormality of the trigeminal nerve. Pathological evidence of intracerebral inflammation in a patient with LSCS has recently been observed by Stone et al. [13]. Accordingly, we suggest that computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are useful diagnostic tools for the investigation of patients with LSCS, in particular for detecting clinically inapparent intracranial changes [13,14]. In the present case, cutaneous atrophy involved both frontal sites. Bilateral lesions of LSCS have been considered to be extremely rare [15]. Lateralization of LSCS possibly indicates a neuropathological etiology of the disease. Notably, there were no preceding clinical features of scleroderma in the atrophic area affecting the right forehead of our patient indicating that the atrophic cleft on the right forehead was caused by profound linear scleroderma [7].

The management of localized scleroderma is still unsatisfactory. Various therapeutic modalities (e.g. topical and pharmacological agents, immunosuppresion, physiotherapy, and phototherapy) have been suggested [16]. In an uncontrolled study, we have recently observed that childhood scleroderma can successfully be treated with topical calcipotriol and low-dose UVA1 phototherapy [17]. However, management of facial atrophy is a challenge. As shown in the presented case, palliative reconstruction surgery is potentially beneficial for patients with disfiguring facial atrophy, and the employment of 3-dimensional reconstuction imaging may be helpful in preoperative scheduling of bony reconstruction surgery [18].

List of abbreviations

LSCS : linear scleroderma "en coup de sabre";

PRS : Parry-Romberg syndrome

Competing interests

None declared

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

We are very grateful to the patient who gave us written consent for publication of her details and figures.

Contributor Information

Thilo Gambichler, Email: t.gambichler@derma.de.

Alexander Kreuter, Email: a.kreuter@derma.de.

Klaus Hoffmann, Email: k.hoffmann@derma.de.

Falk G Bechara, Email: f.bechara@derma.de.

Peter Altmeyer, Email: p.altmeyer@derma.de.

Thomas Jansen, Email: t.janson@derma.de.

References

- Blaszczyk M, Krysicka Janninger C, Jablonska S. Childhood scleroderma and its pecularities. Cutis. 1996;58:141–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuffanelli DL. Localized scleroderma. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1998;17:27–33. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(98)80059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery H. Pediatric scleroderma. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1998;17:41–47. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(98)80061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jappe U, Hölzle E, Ring J. Parry-Romberg syndrome. Review and new observations based on a case with unusual features. Hautarzt. 1996;47:599–603. doi: 10.1007/s001050050475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonska S, Blaszczyk M. Scleroderma-like disorders. Semin Cutan Med Sug. 1998;17:65–76. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(98)80064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann TJA. The Parry-Romberg syndrome of progressive facial hemiatrophy and linear scleroderma en coup de sabre. Mistaken diagnosis or overlapping conditions? J Rheumatol. 1992;19:844–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaszczyk M, Krysicka Janniger C, Jablonska S. Primary atrophic profound linear scleroderma. Dermatology. 2000;200:63–66. doi: 10.1159/000018321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malandrini A, Dotti MT, Federico A. Selective ipsilateral neuromuscular involvement in a case of facial and somatic hemiatrophy. Muscle Nerve. 1997;20:890–892. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(199707)20:7<890::AID-MUS16>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaszczyk M, Jablonska S. Linear scleroderma en coup de sabre. Relationship with progressive facial hemiatrophy (PFH). Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;455:101–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menni S, Marziano AV, Passoni E. Neurologic abnormalities in two patients with facial hemiatrophy and sclerosis coexisting with morphea. Pediatr Dermatol. 1997;14:113–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1997.tb00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suttorp-Schulten MS, Koornnef L. Linear scleroderma associated with ptosis and motility disorders. Br J Ophthalmol. 1990;74:694–695. doi: 10.1136/bjo.74.11.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runne U, Fasshauer K. Idiopathic and sclerodermic facial hemiatrophy with generalized myopathy. Clinical, electromyographic and histologic examinations of six patients. Hautarzt. 1977;28:10–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone J, Franks AJ, Guthrie JA, Johnson MH. Scleroderma "en coup de sabre": pathological evidence of intracerebral inflammation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70:382–385. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.3.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer J, Knollmann FD, Schlecht I, Terstegge K, Felix R. High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging in patients with facial hemiatrophy. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:373–375. doi: 10.1080/000155599750010300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai R, Handa S, Gupta S, Kumar B. Bilateral en coup de sabre – a rare entity. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:222–224. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2000.01757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunzelmann N, Scharffetter Kochanek K, Hager K, Krieg T. Management of localized scleroderma. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1998;17:34–40. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(98)80060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter A, Gambichler T, Avermaete A, Jansen T, Hoffmann M, Hoffmann K, et al. Combined treatment with calcipotriol ointment and low-dose ultraviolet A1 phototherapy in childhood morphea. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:241–245. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2001.018003241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inigo F, Jimenez-Murat Y, Arroyo O, Fernandez M, Yusanza A. Restoration of facial contour in Romberg's disease and hemifacial microsomia: experience with 118 cases. Microsurgery. 2000;20:167–172. doi: 10.1002/1098-2752(2000)20:4<167::AID-MICR4>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]