Abstract

Multicompartmental polymer carriers, referred to as Polyanhy-dride-Releasing Oral MicroParticle Technology (PROMPT), were formed by a pH-triggered antisolvent precipitation technique. Polyanhydride nanoparticles were encapsulated into anionic pH-responsive microparticle gels, allowing for nanoparticle encapsulation in acidic conditions and subsequent release in neutral pH conditions. The effects of varying the nanoparticle composition and feed ratio on the encapsulation efficiency were evaluated. Nanoparticle encapsulation was confirmed by confocal microscopy and infrared spectroscopy. pH-triggered protein delivery from PROMPT was explored using ovalbumin (ova) as a model drug. PROMPT microgels released ova in a pH-controlled manner. Increasing the feed ratio of nanoparticles into the microgels increased the total amount of ova delivered, as well as decreased the observed burst release. The cytocompatibility of the polymer materials were assessed using cells representative of the GI tract. Overall, these results suggest that pH-dependent microencapsulation is a viable platform to achieve targeted intestinal delivery of polyanhydride nanoparticles and their payload(s).

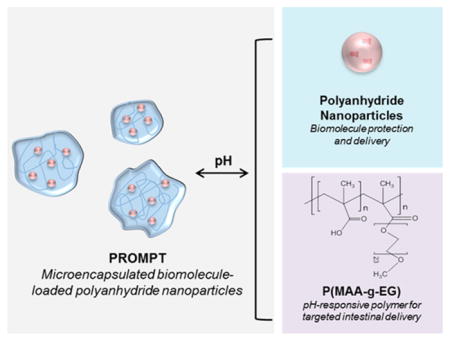

Graphical Abstact

INTRODUCTION

Polymeric carriers have been extensively used for pharmaceutical formulations, providing controlled release of therapeutic agents with tunable control to maintain drug concentration within the therapeutic window.1–3 The increased availability of diverse biological therapeutics has necessitated the development of more complex polymeric systems to achieve payload stability, site-specific targeting, and improved bioavailability.4,5 Macromolecular drugs, a growing subset of biological drugs, includes proteins, peptides, and small interfering RNA (siRNA). These molecules are indicated for use in the treatment, prevention, and management of certain types of cancer therapy, inflammatory diseases, and vaccines. However, the delivery of these macromolecular therapeutics, which are often fragile and poorly absorbed, has largely been restricted to parenteral administration in order to maintain their structure and achieve bioavailability.6

Development of micro- and nanotechnology based formulations offer the opportunity to deliver macromolecular drugs via alternative administration routes with improved patient compliance.7,8 Furthermore, advancement of polymer chemistry has enabled a diversity of intelligent, responsive, and biodegradable carriers in order to tailor release profiles, enhance site-specific targeting, and improve bioavailability.9,10

Oral delivery remains the most desirable delivery route due to the ease of administration. However, development of oral drug delivery systems remains a formidable challenge for sensitive therapeutic agents.11 The gastrointestinal (GI) tract poses harsh barriers to overcome including protein denaturation or degradation in the acidic, proteolytic environment of the stomach, and a narrow delivery window in the highly absorptive region of the small intestine.12 Significant progress has been made in pH-responsive materials that exploit the natural gradient of GI tract to achieve intestinal delivery.13,14 Specifically, pH-responsive hydrogels are a class of materials with extremely desirable properties for oral delivery of protein therapeutics.15–20

In this work, we explored the development of a multi-compartmental system to achieve pH-responsive delivery of biodegradable nanoparticles for the controlled release of biomolecules. This system consists of pH-responsive microgels encapsulating surface-eroding polyanhydride nanoparticles loaded with protein drugs. The pH-responsive microgels are composed of a copolymer of poly(methacrylic acid) (PMAA) with poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) tethers, henceforth designated as P(MAA-g-EG), as shown in Figure 1. Cross-linked P(MAA-g-EG) hydrogels and other similar complexation hydrogel formulations have been developed for oral delivery of therapeutic proteins, such as insulin,21,22 interferon β,23 TNF-α,18 growth hormone,20,24 and even for the design of oral vaccine formulations.25,26 The methacrylic acid has a pKa of 4.8, which corresponds to the natural pH transition between the stomach and small intestine. In the acidic environment of the stomach (pH 1–3), the protonated methacrylic acid in the hydrogel participates in hydrogen bonding and complexation to protect the encapsulated payload. Upon transitioning to the neutral environment of the upper small intestine (pH 5–8), the methacrylic acid deprotonates and the hydrogel swells due to ionization-induced decomplexation and water imbibition to release the payload.27–30 However, cross-linked pH-responsive systems can still face challenges such as low encapsulation efficiency, incomplete release of payload within an efficacious window, and poor encapsulation of hydrophobic and large molecular weight drugs.

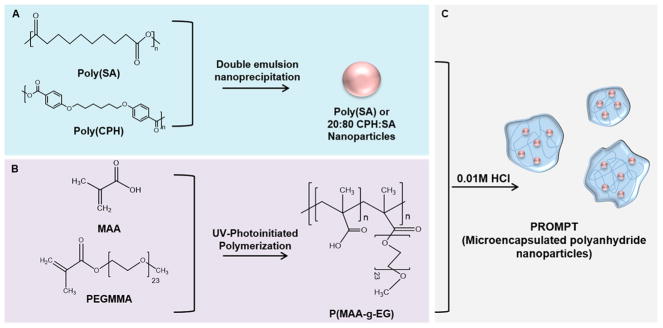

Figure 1.

Synthesis of (A) polyanhydride nanoparticles based on Poly(SA) or 20:80 CPH/SA, and (B) P(MAA-g-EG) polymer by UV-initiated polymerization for (C) the antisolvent precipitation procedure used to produce PROMPT particle dispersions of polyanhydride nanoparticles stabilized by P(MAA-g-EG).

In this work, a pH-triggered self-assembly strategy was explored to improve facile inclusion and release of nano-particles encapsulated within the microgel matrix. The effects of nanoparticle composition and feed ratio during synthesis were investigated with regards to nanoparticle encapsulation efficiency and drug release kinetics from the nanoparticles after their release from the microgel. The encapsulated nanoparticles in the presented studies are composed of polyanhydrides, as described in Figure 1, a class of biodegradable polymers that have been shown to stabilize proteins and sustain their release.31–36 These materials exhibit a surface erosion mechanism that allows the controlled delivery of payloads.37–40 Additionally, manipulation of the polymer hydrophobicity by changing monomer ratios allows for tailored release kinetics and efficient inclusion of hydrophilic and hydrophobic proteins.41–43 In this work, two polyanhydride copolymers based on sebacic acid (SA) and the more hydrophobic 1,6-bis(p-carboxyphenoxy)hexane (CPH) were evaluated.44 Previous work from our laboratories has shown that Poly(SA) and 20:80 CPH/SA are able to preserve protein stability, their release kinetics show an initial burst and sustained release, and both are internalized effectively by different types of immune cells, as shown in Carrillo-Conde et al.45 and Ulery et al.,46 among others. These polyanhydride formulations are also semicrystalline, which was important during the flocculation stage of PROMPT microparticle synthesis.

The multicompartmental system is referred to as Polyanhy-dride-Releasing Oral MicroParticle Technology, or PROMPT. The synthesis, pH-responsive dissociation, and release of a model protein, ovalbumin (ova), were evaluated for potential applications to oral drug delivery. Additionally, cytocompatibility of the polymer materials was assessed using cells representative of the GI tract.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials

All reagents were used as received. Sebacic acid, hydroxybenzoic acid, dibromohexane, 1-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone, meth-acrylic acid (MAA), 1-hydroxycyclohexyl phenyl ketone (Irgacure 184), Span 80, CdSeS/ZnS alloyed quantum dots (λem = 525 nm), and albumin from chicken egg white were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Sodium hydroxide, acetone, sulfuric acid, acetic anhydride, methylene chloride, hexanes, and pentane were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Hanover Park, IL). Polyethylene glycol monomethyl ether methacrylate (PEGMMA, MW 1000) was purchased from Polysciences Inc. (Warrington, PA), and TAMRA-cadaverine was obtained from Biotium (Fremont, CA). (1-Ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride) (EDC) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide and deuterated chloroform were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA). All other solvents and buffers were also obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Reagents used for cell culture were Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), penicillin — streptomycin, and fetal bovine serum from Thermo Fisher Scientific, and L-glutamine from Sigma-Aldrich.

Polyanhydride Monomer and Polymer Synthesis

Prepol-ymers of SA and CPH were synthesized by methods previously described.47,48 Subsequently, poly(SA) homopolymer and 20:80 CPH/SA copolymers were synthesized by melt polycondensation reactions.48,49 The chemical purity and molecular weight of the polymers were characterized with 1H NMR using a Varian VXR 300 MHz spectrometer (Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA). Poly(SA) and 20:80CPH/SA had Mw of 21407 and 17726 Da, respectively.

Polyanhydride Nanoparticle Synthesis

Polyanhydride particles were synthesized via double emulsion nanoprecipitation, as previously described.46 For these studies 20:80 CPH/SA or Poly(SA) (20 mg mL−1) was dissolved in methylene chloride with Span 80 (1% v/v) and the desired payload: either quantum dots (1% v/v) or ova (5 wt %). The polymer solution was sonicated at 50 Hz for 30 s using a probe sonicator (Fisher Scientific Model 50 Sonic Dismembrator) and then rapidly poured into a pentane bath at a solvent to nonsolvent ratio of 1:250. Resulting particles were collected by vacuum filtration (Whatman 50, Fisher Scientific) and their morphology was characterized using scanning electron microscopy, shown in Figure S1 (SEM, Zeiss Supra40 Scanning Electron Microscope, Oberkochen, Germany).

pH-Responsive Polymer Synthesis

P(MAA-g-EG) polymer was synthesized using a UV-initiated free-radical polymerization. Briefly, MAA and PEGMMA were added in a 44:1 molar feed ratio of MAA/PEGMMA, corresponding to a 1:1 molar ratio of hydrogen bonding groups, in a 1:1 (w/w) solution of DI water and ethanol to yield a final 1:5 total monomer to solvent ratio. The photoinitiator Irgacure 184 was added at a 1 wt % with respect to total monomer content. The mixture was homogenized by sonication and then purged of oxygen, a free-radical scavenger, by nitrogen purging the sealed flask for 20 min. Polymerization was initiated using a Dymax BlueWave 200 UV point source (Dymax, Torrington, CT) at 150 mW/cm2 intensity and allowed to proceed for 2 h under constant stirring.

Linear polymer was purified from unreacted monomer by inducing polymerionomer collapse. The polymer solution was adjusted to pH 10 by addition of a 50% sodium hydroxide solution. The polymer was collapsed while keeping the pendant groups ionized by lowering the dielectric constant of the suspension, in this case by addition of acetone, which caused immediate flocculation and sedimentation of the polymer. Polymer was collected by centrifugation (at 4000 rcf for 10 min) and supernatant containing unreacted monomer was removed. The pellet was then resuspended in water and this process was repeated three times. The polymer solution was neutralized, dialyzed against deionized water in 3.5 kDa molecular weight cutoff-dialysis tubing (Spectrum Laboratories, Rancho Dominguez, CA) for 10 water changes and then freeze-dried and stored at room temperature with desiccant.

Copolymer composition was verified by 13C NMR using a Varian DirectDrive 600 MHz nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer (Palo Alto, CA). A minimum of 50 mg of dried polymer was dissolved in 700 μL of D2O. All NMR Spectra were analyzed using MestReNova Software (MestreLab Research, Santiago, Spain). Polymer molecular weight was determined by gel permeation chromatography (GPC) using a Malvern Viscotek TDAmax Triple Detection SEC System (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, Worcestershire, UK), equipped with an A6000 M column. Samples were dissolved in 0.1 M Na2HPO4 to a final concentration of ~4 mg mL−1 for 1 h prior to analysis at 30 °C. For all samples, an injection volume of 100 μL and a flow rate of 1.0 mL min−1 were used. Molecular weight data was calculated using OmniSEC software (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, Worcestershire, U.K.).

Composite Microgel Synthesis

Antisolvent precipitation was used to produce PROMPT formulations by creating particle dispersions of polyanhydride nanoparticles stabilized by P(MAA-g-EG), as demonstrated in Figure 1. Linear P(MAA-g-EG) polymer was dissolved in deionized water (pH 6) at 20 mg mL−1. Polyanhydride nanoparticles were added at varying ratios (10 or 20 wt % relative to polymer content) and sonicated at 50 Hz for 30 s to achieve a dispersed solution. Hydrochloric acid (0.1 N) was used as the antisolvent and introduced at a volumetric ratio of 1:100 to the polymer-nanoparticle dispersion. Upon addition of solvent into the antisolvent phase, particles rapidly formed and began to flocculate. Particles were allowed to flocculate at 4 °C for 30 min before collection by centrifugation (4500 rcf, 5 min) and then dried using a FreeZone freeze dyer (Labconco, Kansas City, MO). The final particles were acquired by crushing the particle pellet with a mortar and pestle to obtain a fine powder.

Scanning Electron Microscopy

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to examine the surface morphology, particle shape, and size of microparticle formulations in the dried state. SEM samples were prepared by dusting carbon-tape covered aluminum stubs with lyophilized and crushed microgels. Samples were coated with 12 nm of platinum/palladium using a Cressington 208HR sputter coater (Watford, England, UK). Coated samples were imaged with a Zeiss Supra 40VP Scanning Electron Microscope (Oberkochen, Germany).

Confocal Microscopy

Confocal microscopy was used to verify nanoparticle incorporation during synthesis. P(MAA-g-EG) was labeled with TAMRA-cadaverine prior to microparticle synthesis by an EDC-NHS reaction. To accomplish this reaction, 200 mg purified P(MAA-g-EG) was mixed with 50 mg EDC and 80 mg NHS in DI water for 2 min, prior to the addition of 52 μL of a 10 mg/mL TAMRA-cadaverine solution. The reaction solution was then incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Labeled P(MAA-g-EG) polymer was washed three times using the ionomer collapse procedure and then freeze-dried.

Polyanhydride nanoparticle formulations encapsulating 1% (v/v) of 525 nm quantum dots were synthesized as described above. Fluorescent P(MAA-g-EG) and quantum dot-loaded nanoparticle formulations were used for microparticle synthesis using the procedure previously described. Fluorescent microgels were sprinkled onto a coverslip and imaged by an FV10i-DOC inverted laser-scanning confocal microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) using a built-in UPLSAPO 10x phase contrast objective (NA = 0.4). All microscope settings were maintained for all images obtained.

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was used to investigate the molecular structure of the polymer starting materials, P(MAA-g-EG) and polyanhydrides, as well as the composite microgels. All spectra were collected from 2500 to 650 cm−1 as the average of 64 scans on a Nicolet iS10 FT-IR Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, U.S.A.) outfitted with Smart iTX accessory for measurement in ATR mode.

pH-Dependent Dissociation

Dissociation of the composite microgels was verified by microscopy using an Olympus IX73 inverted microscope following neutralization of the environmental pH (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Fluorescent microgels containing quantum-dot loaded nanoparticles were hydrated in 0.1 M HCl prior to addition of 50 μL of sodium hydroxide to adjust the pH to 6.5. Bright field and fluorescent images of the dissociation were captured using the 10× objective.

Ovalbumin Release Kinetics from PROMPT Microgels

In vitro release kinetics of ova from PROMPT formulations was quantified using a microbicinchoninic acid (micro BCA) assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Microparticle formulations were suspended at 1 mg/mL in 20 mL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) with 0.01% sodium azide and maintained at 37 °C under constant agitation for the duration of the study. Release samples were collected at 1 h and every other day for 10 days to evaluate sustained release of ova. At each time point, suspensions were centrifuged at 4000 rcf for 10 min, and a 2 mL aliquot was collected and the volume was replaced with fresh PBS. The remaining encapsulated protein was extracted by addition of sodium hydroxide to a final concentration of 50 mM to fully dissociate the polyanhydride nanoparticles.

As a control, the release of ova from the polyanhydride nanoparticle formulations was performed using a similar procedure. Nanoparticles were suspended at 10 mg/mL in PBS with 0.01% sodium azide and maintained at 37 °C under constant agitation for the duration of the study. Release samples were collected via centrifugation (at 10000 rcf for 10 min) at the same time points listed above; supernatant was collected and replenished with fresh buffer. All samples were stored at 4°C until analysis. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Cell Culture

Caco-2 colon adenocarcinoma cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockwell, MD) and cultured in DMEM, supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS, 4 mM L-glutamine, and 1% (v/v) of an antibiotic solution (100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin). Cells were subcultured in T- 75 flasks (at 37 °C) in a 5% CO2 environment. Media was refreshed every 72 h and cells passaged at 80–90% confluency.

In Vitro Cytocompatibility

Cell culture-treated 96-well poly-styrene plates were coated with a 1:100 DPBS/fibronectin solution overnight at 4 °C. The fibronectin solution was aspirated and wells rinsed once with DPBS prior to cell plating. Caco-2 cells were seeded at 25000 cells per well in 200 μL of complete DMEM without phenol red (+10% FBS, 4 mM L-glutamine, 1% P-S). Cells were maintained for 24 h prior to cytocompatibility experiments.

Solutions of microgels were prepared in complete DMEM without phenol red (+10% FBS, 4 mM L-glutamine, 1% P-S) at concentrations ranging from 0.25 to 1 mg/mL. Media was carefully aspirated from all wells and replaced with either 100 μL of a formulation suspension, unmodified growth media as a positive control, or water as a negative control and allowed to incubate for 4 h (at 37 °C and 5% CO2).

Cellular proliferation after formulation exposure was used as an indicator of cell health, as measured by the CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation MTS Assay (Promega, Madison, WI). Briefly, 20 μL of MTS assay solution was added to the treated wells and incubated for 90 min. After incubation, absorbance measurements were made at 490 and 690 nm, using a Biotek Cytation 3 Cell Imaging Multi-Mode Reader (Winoosky, VT, U.S.A.). Cytocompatibility was measured as relative cell proliferation, calculated by subtracting the background absorbance and normalizing to the average absorbance value of the positive control well, using the following equation

| (1) |

The integrity of the cellular membranes after incubation was evaluated using the Promega CytoTox One Homogenous Membrane Integrity Assay (Promega, Madison, WI). A total of 20 min prior to the end of the designated incubation period, plates were removed from the incubator to equilibrate to room temperature. The experimental supernatant (50 μL) was transferred into a fresh black-walled 96-well plate and mixed gently with 50 μL of CytoTox One reagent for 30 s to ensure complete mixing of reagent and supernatant. The samples were incubated for an additional 10 min at room temperature, and then 25 μL of assay stop solution was added to each well. Fluorescence measurements were made with an excitation wavelength of 560 nm and emission wavelength of 590 nm. Percent cytotoxicity was calculated by subtracting the culture medium background (media only, no cells) from all fluorescence values of experimental wells and then normalizing the corrected experimental values relative to the negative control:

| (2) |

Results are reported as relative percent viability, calculated as 100% –% cytotoxicity.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was used to analyze the ova release and cytocompatibility data. Release data was analyzed by two-way ANOVA to compare multiple groups with a posthoc Tukey test to confirm statistical significance between the experimental groups. Cytocompatibility data was also analyzed by ANOVA to compare multiple groups and a posthoc Dunnett’s test was performed to confirm statistical significance of the experimental groups against the media only.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Copolymer Characterization

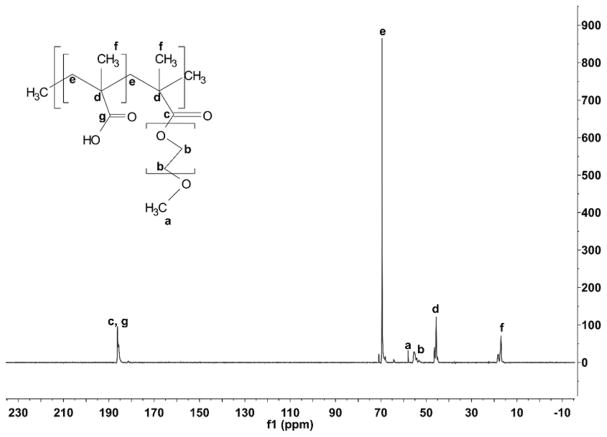

Copolymer composition of the synthesized P(MAA-g-EG) was verified using 13C NMR spectra. The peak assignment and spectra of P(MAA-g-EG) is shown in Figure 2. The relative molar quantity of PEG and MAA in the copolymer was determined by comparing the terminal methyl groups associated with PEG tethers (peak a, 58 ppm) to methyl groups in the copolymer backbone (peak f, 17.3 ppm). Peak assignment was confirmed using 2D Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence Spectroscopy NMR (Figure S2). The resulting P(MAA-g-EG) copolymer was determined to have a 93.9% MAA content, which is in good agreement with the comonomer feed ratio of 95%. Upon analysis by GPC, it was determined that P(MAA-g-EG) had an average molecular weight of 55 kDa.

Figure 2.

13C NMR spectra was used to confirm the molar composition of P(MAA-g-EG) copolymer by comparing the ratio of PEG terminal methyl groups (a) to methyl groups in the polymer backbone (f).

The pH-responsiveness of the copolymer was confirmed by evaluating macromolecular changes in the polymer in response to shifts in environmental pH. Polymer samples were dissolved in aqueous conditions and the pH shifted to 2.0 or 7.0 by addition of hydrochloric acid or sodium hydroxide solutions, respectively, before being lyophilized and analyzed by Attenuated Total Reflection-Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR). Characteristic functional groups were consistent with previously reported spectra, demonstrating ionization of the MAA carboxylic acid group by spectra shifts between pH 2.0 and 7.0 (Figure S3).50–52

PROMPT Microparticle Characterization

Multicompartmental microparticles were prepared by an antisolvent precipitation technique to encapsulate polyanhydride nano-particles with the pH-responsive P(MAA-g-EG) copolymer, as demonstrated in Figure 1. The PROMPT microparticles were synthesized using two different polyanhydride chemistries, Poly(SA) and the more hydrophobic 20:80 CPH/SA.44 Both the composition and the feed ratio were modified in order to evaluate the effects of hydrophobicity during synthesis. Upon transition from neutral to acidic pH conditions, the carboxylic acid groups in P(MAA-g-EG) become protonated, participating in hydrogen bonding to complex the network and providing a more hydrophobic environment favorable for the polyanhydride nanoparticles.27,53

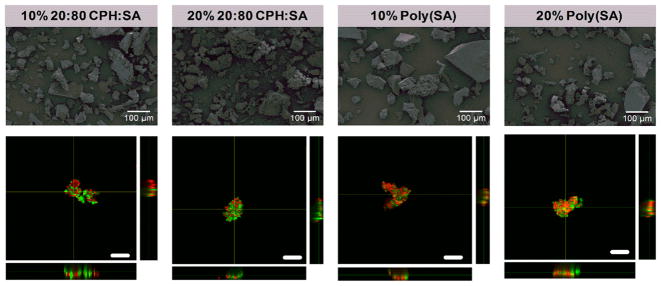

All four formulations exhibit similarly irregular morphology resulting from the preparation process, as shown in the SEM micrographs in Figure 3. Synthesized PROMPT microparticles showed a polydisperse population with a range of sizes from 20 to 200 μm. While SEM micrographs indicated the presence of nanoparticles adsorbed to the microgel surface (Figure 3), confocal microscopy confirmed that nanoparticles were incorporated into the microgels during synthesis. For this experiment, fluorescently tagged P(MAA-g-EG) and quantum dot-loaded nanoparticles were used during synthesis of the microparticles and the corresponding z-stack images obtained. The XY and YZ orthogonal projections from a Z-plane in the middle of the particles, shown in Figure 3, demonstrate that the nanoparticles are incorporated throughout the self-assembled microgels for both the 10% and 20% nanoparticle feed ratios.

Figure 3.

Representative SEM micrographs of PROMPT composite microgels synthesized with 10 and 20% feed ratios of Poly(SA) and 20:80 CPH/SA nanoparticles demonstrate the polydisperse population of particles in the dry state. PROMPT microgels were synthesized as described previously using TAMRA-cadaverine-labeled P(MAA-g-EG) encapsulating polyanhydride nanoparticle formulations with 1% (v/v) quantum dots (λem = 525 nm). Confocal microscopy of fluorescently labeled microgels confirms the inclusion of nanoparticles into the composite microgels during the assembly process. Scale bar = 100 μm.

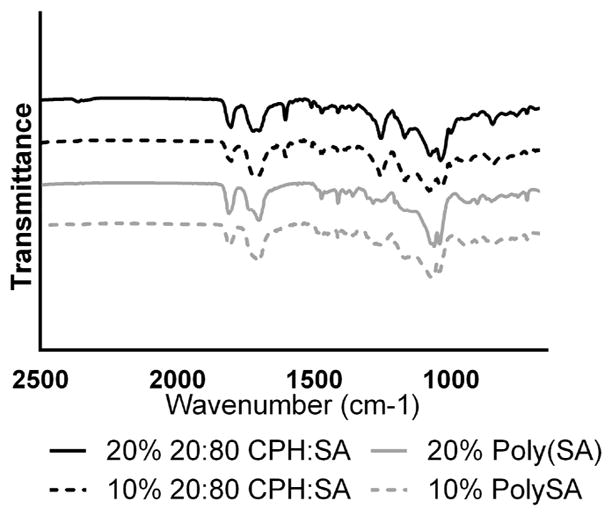

The composition of assembled microparticles was further confirmed by FTIR spectroscopy. The characteristic peak reported for Poly(SA) is the asymmetric carboxyl stretching of the aliphatic anhydride bond at 1810 cm−1 and appeared in the spectra for both the Poly(SA) and 20:80 CPH/SA containing formulations.54,55 Additionally, the 20:80 CPH/SA formulations contain the characteristic CPH peak at 1605 cm−1, indicative of the aromatic ring structure.54,55 As shown in Figure 4, all four formulation spectra are similar, with the primary difference being either the presence of the characteristic CPH peak at 1605 cm−1 in the 20:80 CPH/SA or its absence in the Poly(SA) based formulations. The presence of the P(MAA-g-EG) carboxylic acid peak at 1720–1700 cm−1 confirms the hydrogen bonding or complexation between the polymer and nanoparticles which drives the self-assembly process in acidic conditions.50,51

Figure 4.

ATR-FTIR spectra of PROMPT microgels synthesized by pH-triggered self-assembly of P(MAA-g-EG) and nanoparticle dispersions.

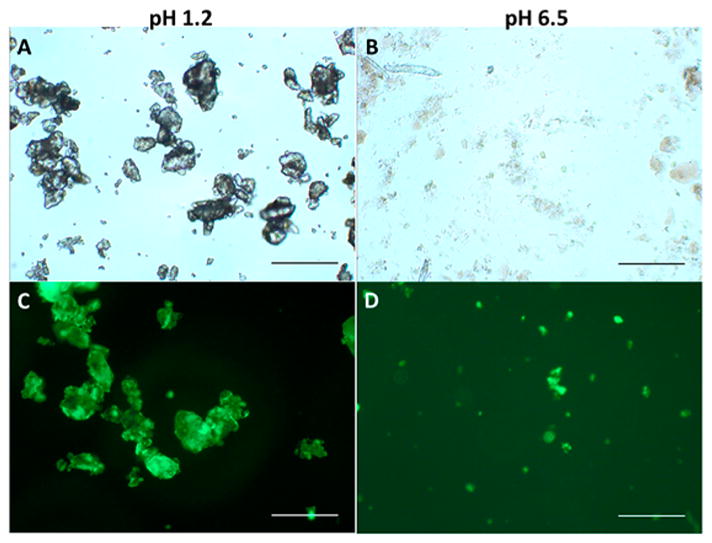

pH-Dependent Dissociation

pH-dependent dissociation of PROMPT formulations to release polyanhydride nano-particles was observed after suspending the microparticles in aqueous solution at pH 1.2 and then adjusting the pH to 6.5. Representative images of 20% Poly(SA) PROMPT microgels demonstrate that the particles remained intact in acidic conditions without an observable release of the fluorescent payload encapsulated within the nanoparticles (Figure 5A,C). The polydispersity of the particle population did not have a significant effect on the rate of dissociation of the microgels, since it occurred very rapidly. Within 1 min of increasing the pH to 6.5 by addition of sodium hydroxide, microgels disintegrated, and released their nanoparticle payload (Figure 5B,D).

Figure 5.

Representative microgel dissociation in intestinal pH conditions. 20% Poly(SA) PROMPT microgels containing PolySA nanoparticles loaded with 1% CdSeS/ZnS quantum dots (λem = 525 nm) remain intact at acidic pH (A, C) and dissociate to release the nanoparticle cargo in neutral pH conditions (B, D). Bright-field (A, B) and fluorescent (C, D) images are shown. Scale bar: 200 μm.

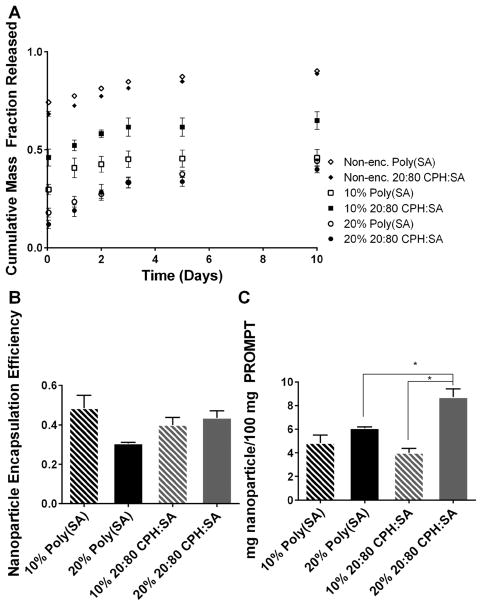

Ovalbumin Release Kinetics from PROMPT Microgels

Release of ova from PROMPT microgels was evaluated to determine (i) the effect of microencapsulation on the release kinetics of the model protein entrapped in the nanoparticles and (ii) the efficiency of the microencapsulation process. Both microencapsulated and nonencapsulated nanoparticles exhibited similar ova release trends, undergoing an initial burst release and subsequent sustained delivery (Figure 6A). However, the burst release of ova from all PROMPT microgel formulations was lower than that observed for the non-encapsulated nanoparticle formulations: ~50% in microgels compared to ~60–70% for nanoparticles. The P(MAA-g-EG) protection shows potential to slow the solvent diffusion into the nanoparticles, thereby mitigating the degree of burst release and enabling a more controlled delivery of encapsulated protein. Furthermore, adjusting the nanoparticle feed ratio during synthesis also had a significant effect on the burst release from the PROMPT formulations. Microgels synthesized with 10% nanoparticle feed ratio exhibited higher fractional burst release when compared to the 20% feed ratio. Dissociation is driven by the hydrophilic nature of the charged groups on P(MAA-g-EG) in neutral pH conditions. Accordingly, microgels synthesized with the lower nanoparticle feed ratio have higher P(MAA-g-EG) content per mass, facilitating a more rapid dissociation of the microgel and exposure of nanoparticle surface area available for protein release.

Figure 6.

Ovalbumin release kinetics from composite microgels. (A) Cumulative mass fraction of ovalbumin released from PROMPT formulations synthesized with 10 and 20% feed ratios of either Poly(SA) or CPH/SA nanoparticle formulations compared to the nonencapsulated (Nonenc.) nanoparticles over the course of 10 days at pH 7.4, as detected by microBCA assay. (B) Encapsulation efficiencies of PROMPT microgels based on nanoparticle feed ratios of 10% and 20% during self-assembly process. (C) Mass of nanoparticles normalized to mass of microgels (n = 3 ± SEM, p < 0.05).

Nanoparticle encapsulation efficiency during the microgel self-assembly process was quantified by comparing the total protein released from PROMPT formulations (determined after extraction) to the total protein loaded into the respective nanoparticle formulation (Figure 6B). The encapsulation efficiency of polyanhydride nanoparticles into the microgel ranged from 30% to 48%, with polyanhydride chemistry having a greater effect than feed ratio. The total mass of the nanoparticles included during the microparticle synthesis was not significantly different between Poly(SA) and 20:80 CPH/SA for the 10% feed ratio, at 4.8 and 3.9 wt %, respectively. However, when the feed ratio was increased to 20% during synthesis, the encapsulated mass of 20:80 CPH/SA significantly increased to 8.7 wt %, maintaining an encapsulation efficiency comparable to that for the 10% feed ratio. However, for the Poly(SA) nanoparticles, the encapsulation efficiency decreased from 48% to 30% as the feed ratio increased from 10% to 20%, with only a slight increase in the mass of nanoparticles included into the composite microparticles, ~6.1 instead of 4.8 wt % (Figure 5C). The increased encapsulation efficiency of 20:80 CPH/SA, as compared to Poly(SA) nanoparticles, is attributed to the more hydrophobic nature of the polymer composition, which would favor the hydrophobic environment created during microgel self-assembly. Conversely, the less hydrophobic Poly(SA) reaches a saturation point during synthesis, after which increased nanoparticle feed ratio does not appear to improve the overall encapsulation efficiency.

These results indicate that higher nanoparticle content in PROMPT microparticles is favorable for reduced burst release of the encapsulated payload and a higher total protein loading. Protein release from PROMPT formulations could ultimately be tailored to achieve a balance between burst release and subsequent sustained delivery by modifying the feed ratio and hydrophobicity of the nanoparticles used during synthesis.

Cytotoxicity

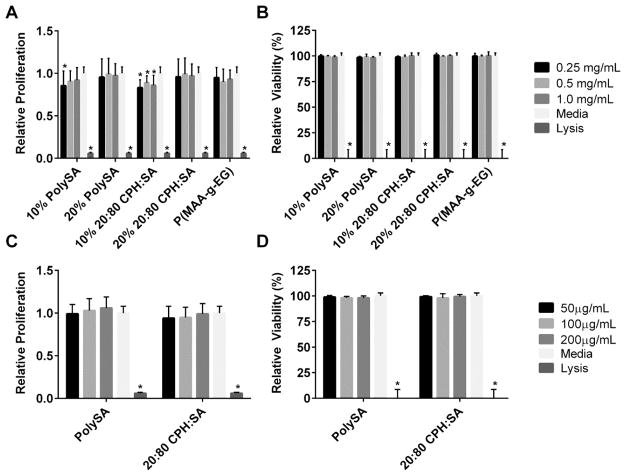

The cytocompatibility of microencapsulated nanoparticle formulations was evaluated in cells representative of the intestinal lining. Caco-2 cells are a human-derived colon carcinoma cell line widely used to evaluate drug absorption across the intestinal epithelium.56,57 Cytocompatibility studies were used to indicate the maximum tolerable concentration without disruption to metabolic activity and membrane integrity (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

In vitro evaluation of the cytocompatibility of PROMPT formulations. Caco-2 colon adenocarcinoma cells were evaluated after 4 h incubations with PROMPT composite microgels (A, B) and their individual components P(MAA-g-EG) (A, B) and polyanhydride nanoparticles (C, D) at varying concentrations. Cytocompatibility was determined by relative cellular proliferation, as measured by MTS proliferation assay (A, C) and membrane integrity, as measured by LDH release using Promega CytoTox One Homogenous Membrane Integrity Assay (B, D) (n = 15 ± SD; *p < 0.05).

Caco-2 cells were exposed to PROMPT composite microgels for 4 h, which corresponds with the average intestinal residence time.58 The relative cellular proliferation of Caco-2 cells incubated with PROMPT microgel formulations, as compared to cells treated with media alone shown in Figure 7A, ranged from 84–99%. The individual components of PROMPT formulations (P(MAA-g-EG) and polyanhydride nanoparticles) were used as controls, as shown in Figure 7A and C, respectively. Interestingly, the only statistically significant effects on cellular proliferation were observed for the 10% Poly(SA) and 10% 20:80 CPH/SA microgel formulations, which have a higher content by mass of P(MAA-g-EG) than the 20% formulations.

Studies have reported reduced viability in the presence of ionizable methacrylic acid groups, which can simultaneously acidify the pH of the cell culture media and chelate the positively charged calcium ions necessary for cellular function.20,59 These observations occurred only at 0.25 mg/mL for the 10% Poly(SA) formulations, but across all concentrations for 10% 20:80 CPH/SA. It is likely this effect is an artifact of the cell culture environment that would not transfer to the much more dynamic physiological environment of the small intestine, in which concentrations of the microgel formulations in contact with cells would not only be much lower, but also subject to constant liquid replacement, that is, perfect sink conditions.20,60 The mild cytotoxicity in the 10% 20:80 CPH/SA formulations could be associated with the slightly increased hydrophobicity of the CPH/SA chemistry, which has been correlated with increased cytotoxicity.61

Nevertheless, a minimum of 80% relative proliferation was observed for all formulations, which has been set as an acceptable threshold to indicate cellular compatibility with biomaterials.20,62,63 In addition to evaluating the effects of the PROMPT particles on cellular proliferation, the effects on cellular membrane integrity were investigated using an LDH membrane integrity assay (Figure 7B). PROMPT individual components were used as controls, as shown in Figure 7B,D. The assay detected release of LDH from disrupted membranes into the culture media by addition of resazurin, which is converted by leached LDH into the detectable fluorescent agent resofurin. PROMPT formulations did not induce any statistically significant release of LDH relative to the cells treated with media, indicating no measurable disruption of the Caco-2 cell membranes.

These results are encouraging, and suggest that the PROMPT formulations represent a promising oral delivery platform. Further evaluation of the safety and efficacy of these systems should be evaluated with prophylactic or therapeutically relevant proteins. One potential application of interest for these systems would be toward development of oral vaccine formulations, in which polyanhydride nanoparticles have demonstrated promising results for subunit antigen administration via the intranasal route and could be tailored for oral delivery.64–66

CONCLUSIONS

A self-assembled microgel strategy was developed for depot delivery of polyanhydride nanoparticles. The P(MAA-g-EG) self-assembly process occurred in a reversible pH-dependent fashion to encapsulate polyanhydride nanoparticles in acidic conditions and selectively release in neutral pH conditions. The multicompartmental PROMPT formulations were synthesized at two feed ratios and with two nanoparticle formulations: Poly(SA) and 20:80 CPH/SA. Modifying the feed ratio and composition of the nanoparticles enabled manipulation of nanoparticle encapsulation efficiency, and accordingly, the release kinetics of encapsulated protein drug. Tailoring the material composition could enable optimization of a desirable balance between burst release and subsequent persistence of the encapsulate payload. Furthermore, PROMPT microgels induced negligible cytotoxic effects in cells representative of the intestinal epithelium. Overall, these results suggest that pH-dependent microencapsulation is a viable platform to achieve targeted intestinal delivery of polyanhydride nanoparticles.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health grant (EB 00246-20), National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (DGE-1610403), and the P.E.O. Scholar Award. The authors would also like to thank the Institute for Cellular and Molecular Biology Microscopy and Imaging Facility for the use of facilities to acquire SEM. B.N. acknowledges the Nanovaccine Institute at Iowa State University and the Vlasta Klima Balloun Faculty Chair.

ABBREVIATIONS

- PMAA

poly(methacrylic acid)

- PEG

poly(ethylene glycol)

- ova

ovalbumin

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- GI

gastrointestinal

- CPH

1,6-bis(p-carboxyphenoxy)hexane

- SA

sebacic acid

- EDC

(1-ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride)

- NHS

N-hydroxysuccinimide

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- GPC

gel permeation chromatography

- FTIR

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

- BCA

bichinchoninic acid

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- P-S

penicillin-streptomycin

Footnotes

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. L.A.S and J.V.R. designed and performed experiments and interpreted the data. L.A.S. wrote the manuscript. O.M.H. executed many of the experiments. K.R. prepared and characterized polyanhydride polymers. B.N. and N.A.P. participated in planning and discussion of the experiments. N.A.P. oversaw the overall execution of the work. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.bio-mac.7b01590.

Further exploration of pH-dependent macromolecular changes and encapsulation of nanoparticles during microparticle self-assembly (PDF).

References

- 1.Liechty WB, Kryscio DR, Slaughter BV, Peppas NA. Polymers for drug delivery systems. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng. 2010;1:149–73. doi: 10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-073009-100847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langer RS, Peppas NA. Present and future applications of biomaterials in controlled drug delivery systems. Biomaterials. 1981;2(4):201–214. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(81)90059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitragotri S, Burke PA, Langer R. Overcoming the challenges in administering biopharmaceuticals: formulation and delivery strategies. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2014;13(9):655–672. doi: 10.1038/nrd4363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh R, Lillard JW., Jr Nanoparticle-based targeted drug delivery. Exp Mol Pathol. 2009;86(3):215–23. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leader B, Baca QJ, Golan DE. Protein therapeutics: a summary and pharmacological classification. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2008;7(1):21–39. doi: 10.1038/nrd2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antosova Z, Mackova M, Kral V, Macek T. Therapeutic application of peptides and proteins: parenteral forever? Trends Biotechnol. 2009;27(11):628–35. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morishita M, Peppas NA. Is the oral route possible for peptide and protein drug delivery? Drug Discovery Today. 2006;11(19–20):905–910. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Škalko-Basnet N. Biologics: the role of delivery systems in improved therapy. Biol: Targets Ther. 2014;8:107–114. doi: 10.2147/BTT.S38387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moghimi SM, Hunter AC, Andresen TL. Factors Controlling Nanoparticle Pharmacokinetics: An Integrated Analysis and Perspective. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;52(1):481–503. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanco E, Shen H, Ferrari M. Principles of nanoparticle design for overcoming biological barriers to drug delivery. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(9):941–951. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moroz E, Matoori S, Leroux JC. Oral delivery of macromolecular drugs: Where we are after almost 100 years of attempts. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2016;101:108–121. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldberg M, Gomez-Orellana I. Challenges for the oral delivery of macromolecules. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2003;2(4):289–295. doi: 10.1038/nrd1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharpe LA, Daily AM, Horava SD, Peppas NA. Therapeutic applications of hydrogels in oral drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Delivery. 2014;11(6):901–915. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2014.902047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mura S, Nicolas J, Couvreur P. Stimuli-responsive nano-carriers for drug delivery. Nat Mater. 2013;12:991–1003. doi: 10.1038/nmat3776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schoener CA, Hutson HN, Peppas NA. pH-responsive hydrogels with dispersed hydrophobic nanoparticles for the oral delivery of chemotherapeutics. J Biomed Mater Res, Part A. 2013;101:2229–36. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshida T, Lai TC, Kwon GS, Sako K. pH- and ion-sensitive polymers for drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Delivery. 2013;10(11):1497–1513. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2013.821978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koetting MC, Peppas NA. pH-Responsive poly(itaconic acid-co-N-vinylpyrrolidone) hydrogels with reduced ionic strength loading solutions offer improved oral delivery potential for high isoelectric point-exhibiting therapeutic proteins. Int J Pharm. 2014;471(1–2):83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carrillo-Conde BR, Brewer E, Lowman A, Peppas NA. Complexation Hydrogels as Oral Delivery Vehicles of Therapeutic Antibodies: An in Vitro and ex Vivo Evaluation of Antibody Stability and Bioactivity. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2015;54:10197–10205. doi: 10.1021/acs.iecr.5b01193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knipe JM, Strong LE, Peppas NA. Enzyme- and pH-Responsive Microencapsulated Nanogels for Oral Delivery of siRNA to Induce TNF-α, Knockdown in the Intestine. Biomacromolecules. 2016;17:788–797. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.5b01518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steichen S, O’Connor C, Peppas NA. Development of a P((MAA-co-NVP)-g-EG) Hydrogel Platform for Oral Protein Delivery: Effects of Hydrogel Composition on Environmental Response and Protein Partitioning. Macromol Biosci. 2017;17(1):1600266. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201600266. n/a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowman AM, Peppas NA. Molecular analysis of interpolymer complexation in graft copolymer networks. Polymer. 2000;41:73–80. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ichikawa H, Peppas NA. Novel complexation hydrogels for oral peptide delivery: in vitro evaluation of their cytocompatibility and insulin-transport enhancing effects using Caco-2 cell monolayers. J Biomed Mater Res. 2003;67:609–17. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamei N, Morishita M, Chiba H, Kavimandan NJ, Peppas NA, Takayama K. Complexation hydrogels for intestinal delivery of interferon β, and calcitonin. J Controlled Release. 2009;134:98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carr DA, Gómez-Burgaz M, Boudes MC, Peppas NA. Complexation Hydrogels for the Oral Delivery of Growth Hormone and Salmon Calcitonin. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2010;49:11991–11995. doi: 10.1021/ie1008025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshida M, Kamei N, Muto K, Kunisawa J, Takayama K, Peppas NA, Takeda-Morishita M. Complexation hydrogels as potential carriers in oral vaccine delivery systems. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2017;112:138–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2016.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durán-Lobato M, Carrillo-Conde B, Khairandish Y, Peppas NA. Surface-Modified P(HEMA-co-MAA) Nanogel Carriers for Oral Vaccine Delivery: Design, Characterization, and In Vitro Targeting Evaluation. Biomacromolecules. 2014;15:2725–2734. doi: 10.1021/bm500588x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lowman AM, Peppas NA. Analysis of the Complexation/Decomplexation Phenomena in Graft Copolymer Networks. Macromolecules. 1997;30:4959–4965. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drescher B, Scranton AB, Klier J. Synthesis and characterization of polymeric emulsifiers containing reversible hydrophobes: poly(methacrylic acid-g-ethylene glycol) Polymer. 2001;42:49–58. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peppas NA, Klier J. Controlled release by using poly(methacrylic acid-g-ethylene glycol) hydrogels. J Controlled Release. 1991;16:203–214. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klier J, Scranton AB, Peppas NA. Self-associating networks of poly(methacrylic acid-g-ethylene glycol) Macromolecules. 1990;23:4944–4949. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tabata Y, Gutta S, Langer R. Controlled Delivery Systems for Proteins Using Polyanhydride Microspheres. Pharm Res. 1993;10(4):487–496. doi: 10.1023/a:1018929531410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Determan AS, Trewyn BG, Lin VS, Nilsen-Hamilton M, Narasimhan B. Encapsulation, stabilization, and release of BSA-FITC from polyanhydride microspheres. J Controlled Release. 2004;100(1):97–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torres MP, Determan AS, Anderson GL, Mallapragada SK, Narasimhan B. Amphiphilic polyanhydrides for protein stabilization and release. Biomaterials. 2007;28(1):108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bakhru SH, Furtado S, Morello AP, Mathiowitz E. Oral delivery of proteins by biodegradable nanoparticles. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2013;65(6):811–821. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mathiowitz E, Jacob JS, Jong YS, Carino GP, Chickering DE, Chaturvedi P, Santos CA, Vijayaraghavan K, Montgomery S, Bassett M, Morrell C. Biologically erodable microspheres as potential oral drug delivery systems. Nature. 1997;386:410. doi: 10.1038/386410a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carino GP, Jacob JS, Mathiowitz E. Nanosphere based oral insulin delivery. J Controlled Release. 2000;65(1):261–269. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00247-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carrillo-Conde BR, Darling RJ, Seiler SJ, Ramer-Tait AE, Wannemuehler MJ, Narasimhan B. Sustained release and stabilization of therapeutic antibodies using amphiphilic polyanhydride nanoparticles. Chem Eng Sci. 2015;125:98–107. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ross KA, Loyd H, Wu W, Huntimer L, Wannemuehler MJ, Carpenter S, Narasimhan B. Structural and antigenic stability of H5N1 hemagglutinin trimer upon release from polyanhydride nanoparticles. J Biomed Mater Res, Part A. 2014;102(11):4161–4168. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vela Ramirez JE, Roychoudhury R, Habte HH, Cho MW, Pohl NLB, Narasimhan B. Carbohydrate-functionalized nanovaccines preserve HIV-1 antigen stability and activate antigen presenting cells. J Biomater Sci, Polym Ed. 2014;25(13):1387–1406. doi: 10.1080/09205063.2014.940243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haughney SL, Petersen LK, Schoofs AD, Ramer-Tait AE, King JD, Briles DE, Wannemuehler MJ, Narasimhan B. Retention of structure, antigenicity, and biological function of pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA) released from polyanhydride nanoparticles. Acta Biomater. 2013;9(9):8262–8271. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vogel BM, Mallapragada SK. Synthesis of novel biodegradable polyanhydrides containing aromatic and glycol functionality for tailoring of hydrophilicity in controlled drug delivery devices. Biomaterials. 2005;26(7):721–728. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Torres MP, Vogel BM, Narasimhan B, Mallapragada SK. Synthesis and characterization of novel polyanhydrides with tailored erosion mechanisms. J Biomed Mater Res, Part A. 2006;76A:102–110. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Determan AS, Graham JR, Pfeiffer KA, Narasimhan B. The role of microsphere fabrication methods on the stability and release kinetics of ovalbumin encapsulated in polyanhydride micro-spheres. J Microencapsulation. 2006;23(8):832–843. doi: 10.1080/02652040601033841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lopac SK, Torres MP, Wilson-Welder JH, Wannemuehler MJ, Narasimhan B. Effect of polymer chemistry and fabrication method on protein release and stability from polyanhydride microspheres. J Biomed Mater Res, Part B. 2009;91B:938–947. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carrillo-Conde B, Schiltz E, Yu J, Chris Minion F, Phillips GJ, Wannemuehler MJ, Narasimhan B. Encapsulation into amphiphilic polyanhydride microparticles stabilizes Yersinia pestis antigens. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:3110–9. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ulery B, Phanse Y, Sinha A, Wannemuehler M, Narasimhan B, Bellaire B. Polymer Chemistry Influences Monocytic Uptake of Polyanhydride Nanospheres. Pharm Res. 2009;26(3):683–690. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9760-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shen E, Pizsczek R, Dziadul B, Narasimhan B. Microphase separation in bioerodible copolymers for drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2001;22:201–210. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kipper MJ, Wilson JH, Wannemuehler MJ, Narasimhan B. Single dose vaccine based on biodegradable polyanhydride microspheres can modulate immune response mechanism. J Biomed Mater Res, Part A. 2006;76(4):798–810. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kipper MJ, Shen E, Determan A, Narasimhan B. Design of an injectable system based on bioerodible polyanhydride microspheres for sustained drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2002;23(22):4405–12. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Torres-Lugo M, Peppas NA. Preparation and Characterization of P(MAA-g-EG) Nanospheres for Protein Delivery Applications. J Nanopart Res. 2002;4(1–2):73–81. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim B, Peppas NA. Analysis of molecular interactions in poly(methacrylic acid-g-ethylene glycol) hydrogels. Polymer. 2003;44:3701–3707. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brock Thomas J, Creecy CM, McGinity JW, Peppas NA. Synthesis and Properties of Lightly Crosslinked Poly((meth)acrylic acid) Microparticles Prepared by Free Radical Precipitation Polymerization. Polym Bull. 2006;57:11–20. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Madsen F, Peppas NA. Complexation graft copolymer networks: swelling properties, calcium binding and proteolytic enzyme inhibition. Biomaterials. 1999;20(18):1701–1708. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(99)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thorstenson JB, Petersen LK, Narasimhan B. Combinatorial/High Throughput Methods for the Determination of Polyanhydride Phase Behavior. J Comb Chem. 2009;11:820–828. doi: 10.1021/cc900039k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vogel BM, Cabral JT, Eidelman N, Narasimhan B, Mallapragada SK. Parallel Synthesis and High Throughput Dissolution Testing of Biodegradable Polyanhydride Copolymers. J Comb Chem. 2005;7(6):921–928. doi: 10.1021/cc050077p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hubatsch I, Ragnarsson EGE, Artursson P. Determination of drug permeability and prediction of drug absorption in Caco-2 monolayers. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(9):2111–2119. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Artursson P, Karlsson J. Correlation between oral drug absorption in humans and apparent drug permeability coefficients in human intestinal epithelial (Caco-2) cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;175:880–885. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91647-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davis SS. Formulation strategies for absorption windows. Drug Discovery Today. 2005;10:249–257. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03351-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Foss AC, Peppas NA. Investigation of the cytotoxicity and insulin transport of acrylic-based copolymer protein delivery systems in contact with caco-2 cultures. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2004;57:447–455. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lai SK, Wang Y-Y, Hanes J. Mucus-penetrating nanoparticles for drug and gene delivery to mucosal tissues. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2009;61(2):158–171. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim ST, Saha K, Kim C, Rotello VM. The role of surface functionality in determining nanoparticle cytotoxicity. Acc Chem Res. 2013;46(3):681–691. doi: 10.1021/ar3000647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carr DA, Peppas NA. Assessment of poly(methacrylic acid-co-N-vinyl pyrrolidone) as a carrier for the oral delivery of therapeutic proteins using Caco-2 and HT29-MTX cell lines. J Biomed Mater Res, Part A. 2010;92A(2):504–512. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Knipe JM, Chen F, Peppas NA. Multiresponsive polyanionic microgels with inverse pH responsive behavior by encapsulation of polycationic nanogels. J Appl Polym Sci. 2014;131(7):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vela Ramirez JE, Tygrett LT, Hao J, Habte HH, Cho MW, Greenspan NS, Waldschmidt TJ, Narasimhan B. Polyanhydride Nanovaccines Induce Germinal Center B Cell Formation and Sustained Serum Antibody Responses. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2016;12(6):1303–1311. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2016.2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Phanse Y, Lueth P, Ramer-Tait AE, Carrillo-Conde BR, Wannemuehler MJ, Narasimhan B, Bellaire BH. Cellular Internalization Mechanisms of Polyanhydride Particles: Implications for Rational Design of Drug Delivery Vehicles. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2016;12(7):1544–1552. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2016.2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ulery BD, Petersen LK, Phanse Y, Kong CS, Broderick SR, Kumar D, Ramer-Tait AE, Carrillo-Conde B, Rajan K, Wannemuehler MJ, Bellaire BH, Metzger DW, Narasimhan B. Rational design of pathogen-mimicking amphiphilic materials as nanoadjuvants. Sci Rep. 2011;1:198–198. doi: 10.1038/srep00198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.