Abstract

Background

We conducted this prospective controlled observational study to compare the effect of ethnicity on the risk of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) between moderate to high-risk African and non-African patients undergoing general anesthesia.

Methods

Using Apfel score risk factors and predicted length of surgery (>30 minutes), 89 moderate to high risk patients undergoing general anesthesia were recruited in a university hospital between March 2009 and November 2010. Thirty patients in the non-African group and 59 patients in the African group were allocated using an ethnicity self identification questionnaire. Intraoperative anesthesia was standardized. PONV was assessed at 0 minutes, 15 minutes, 90 minutes, 180 minutes, and 24 hours. Generalized linear mixed effects models was used to determine the effect of ethnicity on PONV.

Results

Despite similar Apfel scores, cumulative incidence of postoperative nausea was higher in the non-African group at 0 minutes (46.67% vs 22.03%, P = 0.019), 15 minutes (70% vs 23.73%, p<0.001) and 90 minutes (36.67% vs 16.95%, P = 0.04). The non-African group had more episodes of vomiting over 24 hours (13.33% vs 1.69%, P = 0.055). Non-Africans had a 25 times higher reported nausea incidence than Africans over 24 hours.

Conclusion

The incidence of PONV in non-Africans is significantly higher than in Africans. Non-African ethnicity is an independent risk factor for PONV. Current risk prediction models may be limited in multi-ethnic populations and further investigations are warranted to examine ethnicity as a risk factor.

Introduction

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is common after administration of general anesthesia with an overall incidence of 30%, while in high-risk patient groups the incidence may be as high as 70–80% despite newer antiemetic drugs1,2. Although not associated with increased mortality, PONV is uncomfortable for patients, can prolong hospital stay, reduce patient satisfaction and increase costs3,4.

Available scoring systems can predict the risk of PONV with reasonable accuracy facilitating planning of prophylactic and therapeutic strategies. The Apfel scoring system is commonly used and determines the risk of PONV based on four risk factors: female gender, history of motion sickness or PONV, non-smoking status and the use of perioperative opioids1. Ethnicity is not included in the Apfel scoring system which may have an effect on the incidence of PONV. In a metanalysis of studies examining patients undergoing gynecological surgery, country of origin influenced variations of PONV incidence5. Furthermore both laboratory-induced motion sickness, where healthy subjects are seated on a motorised chair simulating motion, and administration of opioids demonstrate an ethnicity bias for nausea and vomiting6–8.

In a non-controlled observational trial Rodseth et al identified ethnicity, defined as the non-African cohort in South Africa, as a significant risk factor for PONV9. A limitation of this study was that the anesthetic technique was not standardized, and a smaller percentage of patients received anti-emetic prophylaxis.

We hypothesize that non-African South African ethnicity increases the risk of PONV following general anesthesia. The primary and secondary objectives of the study were to determine the effect of ethinicity on post operative nausea and post operative vomiting respectively.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Approval

Ethical approval for this study (ethics committee number: M071102) was provided by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa (Chairperson Prof PE Cleaton-Jones) on 23 January 2008.

Institutional approval was obtained from the management of the hospital. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 1975, as revised in 2000. All patients recruited into the study gave written informed consent.

Selection and Description of Participants

Adult patients at moderate to high risk for PONV presenting for elective surgery between March 2009 and November 2010 were recruited on a convenience sampling basis. Risk assessment was performed prior to recruitment using the scheme adapted from Habib et al (Table 1)10. This scheme uses five risk factors: the four factors from the Apfel risk score and expected surgical duration of greater than 30 minutes. The Apfel risk score gives one point each to female gender; history of PONV or history of motion sickness; expected use of perioperative opioids and non-smoking1. Inclusion criteria included 18–70 year old patients presenting for elective surgery, able to give informed written consent, receiving general anesthesia of at least 30 minutes duration with perioperative opioid use expected, ASA 1–3 and at moderate to high risk for PONV. Exclusion criteria included patients who were expected to undergo total intravenous anesthesia or sole regional anesthesia, emergency surgery, and inability to understand the visual analogue scale (VAS) or study questions.

Table 1.

Risk stratification for PONV (Adapted from Habib et al)10.

| Low to Moderate Risk | Moderate to High Risk | High Risk | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria |

A* after one previous procedure OR 2 factors from B† |

A after one previous procedure PLUS ≥ 1 factor from B OR ≥ 3 factors from B |

A after more than one previous procedure PLUS ≥ 1 factor from B |

| Prophylaxis | One Agent | Dual Agent | Multimodal (anti emetic drugs and changing modifiable risk factors) |

A: History of PONV

B: Female gender, Postoperative opioid use, history of motion sickness, non-smoker, expected surgery greater than 30 mins duration

Ethnicity was determined using a self-identification questionaire which is widely thought to be the most appropriate method to categorise patients into racial groups for research, and has been previously validated11. The two ethnicity groups defined a priori were African (indigenous black South African) and non-African (non-black South African).

Conduct of the Study

Intraoperative anesthesia was standardized as follows: dual agent prophylaxis was given to all patients as a combination of ondansetron and dexamethasone at 0.1mg/kg each up to a maximum of 4mg; both prophylactic drugs were given at the time of induction; no nitrous oxide was used and the inhalational agent used for maintenance was isoflurane; propofol was the induction agent for the anesthetic, and a single dose of neostigmine (2.5mg) was given to reverse the neuromuscular blocker. The remainder of the anesthetic was left to the discretion of the anesthesia provider. Postoperative management of nausea and vomiting was at the discretion of the anesthesia provider and the floor nurse.

A 10 point visual analogue scale (VAS) was used to assess the degree and presence of postoperative nausea (PON) at 0, 15, 90 and 180 minutes and 24 hours. The use of a VAS at these time points has been validated in previous studies for assessing PONV12. All patients were interviewed by a single researcher at all time intervals and asked the question “Do you feel nauseous?”. The degree of nausea was assessed with a VAS if the patient responded “yes”. All questions were in the patient’s native language. Zero on the VAS was considered to be no nausea, and 10 was considered to be the worst possible nausea. T0 was defined when the patient was alert (Glasgow Coma Score of 15) and able to answer questions in the recovery room. Any episode of postoperative vomiting (POV) within 24 hours of surgery was recorded.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R (Version 3.2.1)13. Demographic and intraoperative data was analysed using Student t-test or Pearson Chi Squared test where appropriate. A Bonferroni corrected alpha (α = 0.003) was used to indicate statistical significance for intraoperative variables. To account for the within-patient correlations of nausea incidence over time, generalized linear mixed effects models (GLMMs) were used to examine the incidence of nausea over time. Using the glmer() function in the “lme4” package, a random intercept by patient was included in all the GLMMs13,14.

To examine the incidence of vomiting across the 24 hour period, generalized linear models (GLMs) were modeled using the “glm()” function in the base R13.

Sample size was calculated using G-Power (Franz Fauk, University of Kiel, Version 3.1.8). A power of 0.95, an alpha of 0.05 and a Cohen’s f2 effect size of 0.15 (medium effect) resulted in a required total sample size of 89. The sample size calculation was initially computed for the incidence of PONV as the outcome variable using ethnicity as the main independent variable. Other co-variates included were gender, smoking status, expected perioperative opioid use and a history of PONV or motion sickness. Although the sample size was calculated for multiple logistic regression, once recruitment had commenced, it was deemed more suitable to use GLMM to take into account the repeated nature of the dichotomous nausea incidence reports over time. Given that only a few incidences of vomiting was reported across the 24 hour period, GLM was more appropriate to model the dichotomous nature of vomiting incidence.

Results

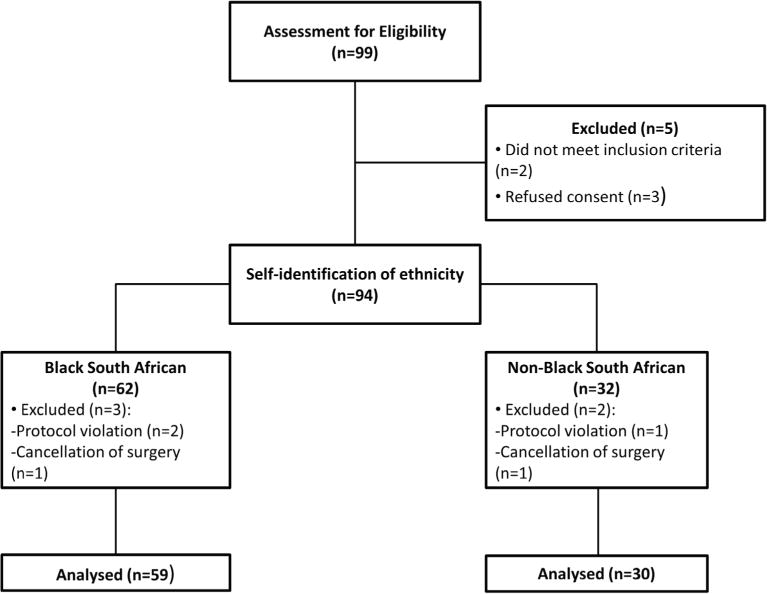

A total of 94 patients were recruited, with 5 exclusions due to: protocol violation in 2 cases; cancellation of surgery in 2 cases and loss to follow-up in 1 case (Figure 1). There were 59 patients in the African group and 30 patients in the non-African group.

Fig. 1.

Recruitment diagram showing the flow of participants through the study.

Demographic and Intraoperative Variables

Demographic data and procedure type are shown in Table 2. Although there were fewer patients with a history of PONV and less non-smokers in the African patient group, the mean Apfel scores between the two groups were not different.

Table 2.

Comparison of baseline variables.

| All (n=89) | African (n = 59) | Non-African (n=30) | P- value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age (yrs) | 41 ± 12 | 39 ± 10 | 44 ± 14 | 0.035 |

|

| ||||

| Anesthetic duration (mins) | 120 ± 67 | 120 ± 73 | 122 ± 5 | 0.909 |

|

| ||||

| ASA, Median [Range] | 1 [1–3] | 1 [1–3] | 1 [1–2] | 0.670 |

|

| ||||

| Gender (% Female) | 81 | 81 | 80 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||

| History of PONV (%) | 18 | 12 | 30 | 0.070 |

|

| ||||

| History of motion sickness (%) | 30 | 27 | 37 | 0.495 |

|

| ||||

| Smokers (%) | 9 | 2 | 23.33 | 0.003 |

|

| ||||

| Procedure (%) | 0.036 | |||

| Gynecology | 48 | 54 | 37 | |

| Orthopedics | 1 | 2 | 0 | |

| Breast | 8 | 7 | 10 | |

| Otolaryngology | 9 | 10 | 7 | |

| Maxillofacial | 13 | 17 | 7 | |

| Plastics | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| Opthalmology | 6 | 6 | 10 | |

| General Surgery | 11 | 3 | 27 | |

|

| ||||

| Apfel Score(mean±SD) | 3.13±0.43 | 3.14± 0.39 | 3.13 ± 0.51 | 0.982 |

| Median [Range] | 3[3–4] | 3[2–4] | 3[2–4] | |

PONV; postoperative nausea and vomiting

ASA-American Society of Anesthesiologists score

All patients in the non-African group were Caucasian in origin. African patients were significantly younger than non-African patients, were less likely to have history of PONV or reported as smokers. The proportions of types of procedures also differed by ethnicity. This is apparent with more patients in the African group undergoing gynecological surgery and more patients in the non-African group undergoing general surgical procedures. This is an unsurprising result, as the majority of patients presenting for gynecological surgery in our hospital are of black South African ethnic origin, with less proportionately black South African patients presenting for general surgeries. Other surgical procedures also had similar differences.

Differences in intraoperative variables between African and non-African patients are presented in Table 3. Using a Bonferroni corrected α of 0.003, as calculated for 19 variables, there were no significant differences in intraoperative variables. All patients received intraoperative opioids. Postoperatively, there was no additional opioid or antiemetic given to patients from both groups between T0 and 15 minutes. Data for opioid and anti-emetic ingestion from 15 minutes to 24 hours was not collected.

Table 3.

Comparison of intraoperative variables. Values are given are given as mean ± standard deviation.

| All (n= 89) |

African (n = 59) |

Non-African (n = 30) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystalloid (ml) | 1069 ± 402 | 1097 ± 404 | 1013 ± 400 |

| Colloid (ml) | 58 ± 176 | 79 ± 203 | 17 ±91 |

| FiO2 (Fraction) | 0.54 ± 0.06 | 0.54 ± 0.07 | 0.55 ± 0.06 |

| Neostigmine (mg) | 2.19 ± 0.82 | 2.20 ±0.82 | 2.17 ± 0.86 |

| Propofol (mg) | 159 ± 50 | 158 ± 44 | 160 ± 61 |

| Fentanyl (mcg) | 100 ± 82 | 98 ± 77 | 103± 92 |

| Morphine (mg) | 8 ± 4 | 8 ± 5 | 7 ± 4 |

| Sufentanil (mcg) | 0.5 ± 4 | 0 | 1 ± 7 |

| Alfentanil (mcg) | 53 ± 220 | 68± 254 | 23 ± 128 |

| IV paracetamol (g) | 1 ± 1.5 | 1 ± 1 | 1 ± 2 |

| Remifentanil (ng/kg/min) | 55 ± 111 | 65 ± 125 | 35 ± 74 |

| Midazolam (mg) | 1 ± 0.4 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.03 ± 0.2 |

| Ketorolac (mg) | 7 ± 13 | 7 ± 13 | 6 ± 12 |

| Atracurium (mg) | 32 ± 21 | 36 ± 19 | 25 ± 22 |

| Rocuronium (mg) | 5± 16 | 1.7± 9 | 10±24 |

| Cisatracurium (mg) | 0.24 ± 1.4 | 0.05 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 2 |

| Vecuronium (mg) | 0.13 ± 1.3 | 0 | 0.4 ± 2.2 |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate (g) | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 1.2±0.8 | 1±0.7 |

| Cefazolin (g) | 0.20±0.5 | 0.2±0.4 | 0.2±0.6 |

| Postop (T0-15mins) Opioid | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Antiemetics | 0 | 0 | 0 |

VAS Scores

The average VAS scores for postoperative nausea in African and non-African patients are presented in table 4.

Table 4.

Average VAS scores for postoperative nausea. Values are given are given as mean ± standard deviation.

| Time | African (n=59) |

Non-African(br.)(n=30) | P- value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 min | 1±2 | 1.9±2.67 | 0.07 |

| 15 min | 0.84±1.74 | 3.06±3.18 | < 0.0001 |

| 90 min | 0.38±0.93 | 1.30±2.07 | 0.0052 |

| 180 min | 0.17±0.95 | 0.46±1.52 | 0.26 |

| 24 hrs | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

Incidence of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting

The incidence of PON and POV at different time points for African and non-African patients based on the total event rate and the total number of observations across all participants is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting based on total event rate.

| Time | African (n=59) |

Non-African (n=30) |

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PON | n | (%) | n | % | |

| 0 min | 13 | (22.03) | 14 | (46.67) | 0.02 |

| 5min | 14 | (23.73) | 21 | (70.00) | < 0.0001 |

| 90 min | 10 | (16.95) | 11 | (36.67) | 0.04 |

| 180 min | 3 | (5.08) | 3 | (10) | 0.39 |

| 24 hrs | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 1.00 |

| 0–24 hours | 40 | (13.55) | 49 | (32.67) | <0.0001 |

| POV | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| 0–24 hours | 1 | (1.69) | 4 | (13.33) | 0.024 |

There was a significantly higher incidence of PON in the non-African group, with exceptions at 180 minutes and 24 hours. At 180 minutes, the incidence of PON was higher in the non-African group, but not significant. At 24 hours there were no incidents of PON in both groups. Over the total 24 hour study period, the incidence of PON was higher in the non-African group (32.67%) as compared with the African group (13.56%).

As none of the patients reported more than one episode of vomiting over the 24-hour period, the incidence of POV was accumulated over the 24 hours study period after surgery. During this period there were a total of 5 (5.62%) incidences of POV; 1 (1.69%) in African patients and 4 (13.33%) in non-African patients reported incidences of POV.

When the incidence of PON is calculated based on a maximum of a single PON event per patient, a similar result is obtained. On examining early PON, between 0–2 hours, non-Africans had a much higher incidence of PON at 73.4% versus Africans at 27.1%. Equally over the whole 24 hr period, non-Africans demonstrated a higher incidence of PON (73.4%) than Africans(28.8%)(Table 6).

Table 6.

Incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting based on any one single event.

| PON | African (n=59) |

Non-African (n=30) |

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| Time period | |||||

| 0–24 hours | 17 | (28.81) | 22 | (73.40) | <0.0001 |

| 0–2 hours | 16 | (27.10) | 22 | (73.40) | < 0.0001 |

| 2–24 hours | 3 | (5.08) | 3 | (10) | 0.40 |

| POV | n | (%) | n | (%) | 0.10 |

| 0–24 hours | 1 | (1.69) | 4 | (13.33) | |

Data Modeling For the Risk of Postoperative Nausea

Among the four risk factors used to compute Apfel scores, only history of PONV was found to be associated with increased odds of PON (P = 0.02) among all patients in the current sample. Thus, Model 1 examined the effect of ethnicity on incidences of nausea over time, controlling for patients’ age and history of PONV. Given that Apfel scores are used to determine the risk of PONV, Model 2 examined the effect of ethnicity on incidences of nausea over time, controlling for patient’ ages and Apfel scores (Table 7).

Table 7.

Results for GLMM analysis of postoperative nausea.

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | 95%CI | P value | OR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Model 1 | Intercept | −2.86 | 1.72 | −6.93, 0.18 | 0.096 | 0.057 | |||||

| Time (hour) | −1.26 | 0.23 | −1.77, −0.84 | <0.0001 | 0.285 | ||||||

| Age | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.09, 0.07 | 0.731 | 0.987 | ||||||

| History of PONV | 2.01 | 1.18 | −0.24, 4.75 | 0.089 | 7.435 | ||||||

| Ethnicity (non-African) | 3.25 | 1.14 | 1.34, 5.97 | 0.004 | 25.695 | ||||||

| σ2 intercept | 11.20 | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Model 2 | Intercept | −8.87 | 3.67 | −17.58, −2.40 | 0.016 | 0 | |||||

| Time | −1.25 | 0.23 | −1.76, −0.84 | <0.0001 | 0.286 | ||||||

| Age | −0.003 | 0.04 | −0.08, 0.07 | 0.931 | 0.997 | ||||||

| Apfel Score | 1.89 | 1.00 | 0.01, 4.21 | 0.057 | 6.642 | ||||||

| Ethnicity(non-African) | 3.52 | 1.13 | 1.64, 6.22 | 0.002 | 33.863 | ||||||

| σ2 intercept | 10.70 | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Model 3 | Intercept | −3.06 | 1.78 | −7.33, 0.02 | 0.085 | 0.047 | |||||

| Time | −1.26 | 0.24 | −1.79, −0.84 | <0.0001 | 0.283 | ||||||

| Age | −0.001 | 0.04 | −0.08, 0.08 | 0.983 | 0.999 | ||||||

| Smoker | −3.19 | 1.86 | −7.69, 0.14 | 0.087 | 0.041 | ||||||

| Ethnicity(non-African) | 4.16 | 1.34 | 2.04, 7.50 | 0.002 | 63.912 | ||||||

| σ2 intercept | 11.40 | ||||||||||

Model 1 showed that one unit (i.e., one minute) increase in the amount of postoperative time is associated with a 0.02 unit decrease in the expected log odds of nausea incidence. The odds of reporting a nausea incident is statistically lower with increased postoperative time (P< 0.01). Controlling for the other variables, patients’ age is not associated with odds of nausea incidence. The odds of reporting PON are 7 times higher for patients with history of PONV than those with no history of PONV: however after controlling for postoperative time, patients’ age and ethnicity, this association did not reach statistical significance. Taking into account the other variables in the model, non-African patients are expected to have 3.3 higher log odds of reporting PON across time than African patients. Even after controlling for patients’ age and history of PONV, the odds of reporting PON are approximately 25 times higher for non-African patients than African patients (P = 0.004) when averaged over 24 hours.

Results in Model 2 showed that non-African patients are expected to have 3.5 higher log odds of reporting PON across time than African patients. Even after controlling for patients’ age and Apfel score, the odds of reporting PON are approximately 33 times higher for non-African patients than African patients (P = 0.002). Similarly, the odds of reporting PON are 6 times higher for patients with one unit increase in Apfel score, after controlling for patients’ age and ethnicity; however, this association did not reach statistical significance. Taken together, results in Models 1 and 2 indicate that patients’ ethnicity has a significant effect on incidence of PON, with non-African patients much more likely to report PON.

Results in Model 3 showed that smokers are 0.04 times less likely to report PON although this was not statistically significant (P = 0.087).

Data Modeling For the Risk of Postoperative Vomiting

As previously described, incidences of POV were accumulated over the 24-hour period after surgery. In order to compare results estimating incidence of POV to those estimating PON, the same control variables, with the exception of postoperative time, were used. Results of the GLMs are summarized in Table 8.

Table 8.

Results for GLM analysis of postoperative vomiting.

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | 95%CI | p-value | OR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Model 1 | Intercept | −3.356 | 1.651 | −7.1, −.37 | 0.042 | 0.035 | ||||

| Age | −0.023 | 0.038 | −0.1, 0.05 | 0.535 | 0.977 | |||||

| History of PONV | 0.978 | 1.069 | −1.3, 3.09 | 0.36 | 2.658 | |||||

| Ethnicity (non-African) | 2.158 | 1.172 | 0.1, 5.19 | 0.066 | 8.658 | |||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Model 2 | Intercept | −7.645 | 3.471 | −15.04, −1.06 | 0.028 | 0 | ||||

| Age | −0.021 | 0.037 | −0.10, 0.05 | 0.575 | 0.979 | |||||

| Apfel Score | 1.339 | 0.974 | −0.59, 3.34 | 0.169 | 3.817 | |||||

| Ethnicity (non-African) | 2.343 | 1.188 | 0.28, 5.40 | 0.049 | 10.41 | |||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Model 3 | Intercept | −3.438 | 1.757 | −7.34, −0.22 | 0.05 | 0.032 | ||||

| Age | −0.016 | 0.039 | −0.10, 0.06 | 0.681 | 0.984 | |||||

| Smoker | −16.878 | 2246.232 | NA, 255.99 | 0.994 | 0 | |||||

| Ethinicity (non-African) | 2.579 | 1.171 | 0.54, 5.61 | 0.028 | 13.181 | |||||

Results in Model 1 showed that neither patients’ age nor history of PONV was associated with incidences of POV. After controlling for patients’ age and history of PONV, non-African patients are expected to have 2.2 higher log odds of reporting POV than African patients, suggesting that the odds of reporting POV are approximately 8 times higher for non-African patients than African patients. However, such difference did not reach statistical significance.

Similar results were found in Model 2; POV incidence was not associated with patients’ age or Apfel scores. Compared to African patients, non-African patients are expected to have 2.3 higher log odds of reporting POV, after controlling for patients’ age and Apfel scores, indicating the odds of reporting POV are approximately 10 times higher for non-African patients than African patients. Although the difference reached statistical significance (P = 0.049), it is premature to draw conclusions based on such few incidences of POV among the study sample. None of the patients who experienced POV were smokers and therefore the interpretation of Model 3 is limited.

Discussion

The incidence of PONV in the non-African group is similar to the predicted risk given by the Apfel score1: however this overestimated the PONV risk in the African patient group at each time point. Despite the Apfel score predicting a 39% to 78% risk of PONV for both groups, the incidence of PON from 0 to 180 minutes was significantly lower at each time point in the the African patient group. In addition, the cumulative incidence of PON over the 24 hour study period was higher in non-African patients based on any single event per patient reporting and total nausea events reporting.

Our results are consistent with Rodseth et al, who demonstrated that African ethnicity decreased the incidence of PONV9. An observational study from Ugochukwu et al demonstrated a lower than predicted incidence of PONV in Nigerian patients undergoing obstetric and gynecology procedures. The authors conclude that this result may be due to ethnic or racial variations15. There is no data currently available directly examining variations in PONV risk based on non-African ethnicity.

The effect of ethnicity on PONV is likely to be multifactorial and may be related to both pharmacogenetic and cultural factors. Patient response to both anti-emetics and pro-emetics (such as opioids) differs based on pharmacogenetic mechanisms. Genetic polymorphisms in the cytochrome P450 system, particularly the number of alleles of CYP2D6, affect the efficacy of 5HT3 receptor antagonists16–19. Variations of 5-HT3A/B receptor genes (HTR3A/HTR3B) have been shown to be associated with the individual risk of developing POV20. Opioid efficacy is affected by genetic polymorphisms of the OPRM1 A118G mu-opioid receptor gene21. implying that the more efficacious an opioid, the higher the risk of PONV, however this has been refuted in a study by Zhang et al22. Other receptor polymorphisms such as the dopamine D2 receptor Taq 1A polymorphism have also been associated with PONV23. These pharmacogenetic mechanisms may be vertically transmitted, and would explain ethnicity related differences in PONV.

A genome wide association study by Janicki et al found that at least one single nucleotide polymorphism was associated with PONV susceptibility24. Based on the results in this study, further studies of genetic association examining PONV susceptibility may be strengthened by the purposeful inclusion of various ethnicities from different geographic locations.

Cultural factors may play a role in the assessment of PONV. Although not in the context of PONV, there is evidence of differences between ethnic and cultural groups in the perception of pain25. This could also potentially be applied to explain ethnic group differences in PONV perception. Further work needs to be done to investigate the possible sociocultural and psychological factors that may influence the assessment and therefore the incidence of PONV.

Our study has several limitations. The sample size was smaller than recommended for studying PONV, but repeated measurements for nausea and vomiting over the study period were utilized12. The use of GLMMs and GLMs for analysis of this longitudinal data was therefore considered appropriate.

Patients were recruited on a convenience basis and not consecutively. This factor and the proportion of ethnic groups presenting to the study hospital played a role in determining the unequal group sizes. However, despite using convenience sampling, no significant differences in baseline variables were present.

Postoperative opioid and anti-emetic data was only available for T0 to 15 minutes. Postoperative medications of this nature could have an effect on PONV. However, the highest incidences of PONV were at T0 and 15 minutes. Therefore, only measurement points after 15 minutes would have been possibly affected by any additional pro or anti-emetic medication given.

Although these results are strictly only applicable to South African, and potentially sub-Saharan African patients, this study does add to the pool of existing international literature suggesting that ethnic origin may be an independent risk factor for PONV. Furthermore such data could be used in the design of further trials to provide insight into the underlying molecular mechanisms responsible for PONV and development of new antiemetic molecules.

In summary, the utility of current risk prediction models may be limited in multi-ethnic populations and further work needs to be done on modified prediction models to include ethnicity as an independent risk factor for PONV as well as determining if such risk is vertically transmitted within population groups.

References

- 1.Apfel CC, Laara E, Koivuranta M, Greim CA, Roewer N. A simplified risk score for predicting postoperative nausea and vomiting: conclusions from cross-validations between two centers. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:693–700. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199909000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen MM, Duncan PG, Deboer DP, Tweed WA. The postoperative interview: assessing risk factors for nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 1994;78:7–16. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gold BS, Kitz DS, Lecky JH, Neuhaus JM. Unanticipated admission to the hospital following ambulatory surgery. JAMA. 1989;262:3008–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myles PS, Williams DL, Hendrata M, Anderson H, Weeks AM. Patient satisfaction after anesthesia and surgery: results of a prospective survey of 10 811 patients. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84:6–10. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bja.a013383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haigh CG, Kaplan LA, Durham JM, Dupeyron JP. Nausea And vomiting after gynaecological surgery: A meta-analysis of factors affecting their incidence. Br J Anaesth. 1993;71:517–22. doi: 10.1093/bja/71.4.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stern RM, Hu S, Leblanc R, Koch K. Chinese hypersusceptibility to vection-induced motion sickness. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1993;64:827–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klosterhalfen S, Kellermann S, Pan F, Stockhorst U, Hall G, Enck P. Effects of ethnicity and gender on motion sickness susceptibility. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2005;76:1051–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cepeda MS, Farrar JT, Baumgarten M, Boston R, Carr DB, Strom B. Side effects of opioids during short term administration: Effect of age, gender, and race. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;74:102–12. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(03)00152-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodseth RN, Gopalan PD, Cassimjee HM, Goga S. Reduced incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting in black South Africans and its utility for a modified risk scoring system. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:1591–4. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181da9005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Habib AS, Gan TJ. Evidence-based management of postoperative nausea and vomiting: a review. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:326–41. doi: 10.1007/BF03018236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Risch N, Burchard E, Ziv E, Tang H. Categorization of humans in biomedical research: genes, race and disease. Genome Biol. 2002;3:1–12. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-comment2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Apfel CC, Roewer N, Korttila K. How to study postoperative nausea and vomiting. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2002;46:921–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2002.460801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Core R, Team R . A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2015. Available from: http://www.R-project.org/. [Accessed 02 February 2016] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bates D, Machler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ugochukwu O, Adaobi A, Ewah R, Obioma O. Postoperative nausea and vomiting in a gynecological and obstetrical population in South Eastern Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2010;7 doi: 10.4314/pamj.v7i1.69111. Epub (19 October 2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Candiotti KA, Birnbach DJ, Lubarsky DA, et al. The impact of pharmacogenomics on postoperative nausea and vomiting: do CYP2D6 allele copy number and polymorphisms affect the success or failure of ondansetron prophylaxis? Anesthesiology. 2005;102(3):543–9. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200503000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sweeney BP. Why does smoking protect against PONV? Br J Anaesth. 2002;89:810–3. doi: 10.1093/bja/aef269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaiser R, Sezer O, Papies A, et al. Patient-tailored antiemetic treatment with 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptor antagonists according to cytochrome P-450 2D6 genotypes. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2805–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brockmoller J, Kirchheiner J, Meisel C, Roots I. Pharmacogenetic diagnostics of cytochrome P450 polymorphisms in clinical drug development and in drug treatment. Pharmacogenomics. 2000;1:125–51. doi: 10.1517/14622416.1.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rueffert H, Thieme V, Wallenborn J, et al. Do variations in the 5-HT3A and 5-HT3B serotonin receptor genes (HTR3A and HTR3B) influence the occurrence of postoperative vomiting? Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1442–7. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181b2359b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chou WY, Wang CH, Liu PH, Liu CC, Tseng CC, Jawan B. Human opioid receptor A118G polymorphism affects intravenous patient-controlled analgesia morphine consumption after total abdominal hysterectomy. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:334–7. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200608000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang W, Yuan JJ, Kan QC, Zhang LR, Chang YZ, Wang ZY. Study of the OPRM1 A118G genetic polymorphism associated with postoperative nausea and vomiting induced by fentanyl intravenous analgesia. Minerva Anestesiol. 2011;77:33–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakagawa M, Kuri M, Kambara N, et al. D2 receptor Taq IA polymorphism is associated with postoperative nausea and vomiting. J Anesth. 2008;22:397–403. doi: 10.1007/s00540-008-0661-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janicki PK, Vealey R, Liu J, Escajeda J, Postula M, Welker K. Genome-wide Association study using pooled DNA to identify candidate markers mediating susceptibility to postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:54–64. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31821810c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rahim-Williams B, Riley Jl, III, Williams AK, Fillingim RB. A Quantitative Review of Ethnic Group Differences in Experimental Pain Response: Do Biology, Psychology, and Culture Matter? Pain Med. 2012;13:522–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01336.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]