Abstract

Nobel Prize is the highest honor in the scientific community that is bestowed for the contribution of eminent scientists in various spheres of science. Since its inception in 1901, many renowned scientists have received this award. However, when compared to men, women's share as recipients is abysmally low. Although the contribution of female scientists has tremendously increased in the last few decades, yet the lack of proportionate increase in recognition is conspicuous by its disproportionate number of women recipients. This paper addresses this issue and underlines some of the reasons contributing to an underrepresentation of women scientists among Nobel Laureates.

Keywords: Nobel prize, Women, Science, Gender bias

Introduction

Nobel Prize, by far is the most honorable and prestigious award in the academic field particularly research. One hundred fifteen years since its first award ceremony in 1901, it has transformed into a very prestigious honor in the world, though nothing has changed with respect to the proportion of women Nobel laureates having received this coveted award in the past century. Although there has been an increase in the number of women aspirants in the field of research in the recent past, the percentage of women scientists holding the top positions in research or having won this award is very low. A cursory analysis of the sheer number of chief editors of top research journals reveals the dominance of male scientists providing leadership in research publications. Besides, the share of female scientists in academic societies is also negligible. Are these trends the result of persistent male dominance and gender discrimination across the globe? An attempt is made here to examine why women have always encountered discrimination leading to serious handicaps in securing recognition in the scientific world.

Sixty Years to Find Another Curie?

A very small fraction of Nobel laureates, accounting for a total of 46 females (with Marie Curie having been awarded twice), makes the analysis of Nobel Prize award very compelling. Out of these 46 women, only 16 were awarded Nobel Prize for their contribution in research while the remaining 30 women obtained the prize in economics, literature and peace.

The first woman Nobel Laureate in the field of Physics was Marie Curie who was awarded for her work on radiation in year 1903 [1]. For the next about 6 decades, none of the women physicists was found eligible to receive this honor. Sixty years later, Maria Goeppert-Mayer, another female physicist, shared this prestigious award with Wigner and Jensen in 1963. In 1911 again, Marie Curie became the first woman to have been bestowed with this honour in Chemistry followed by her daughter Irene-Joliet Curie who was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1935. In Physiology and Medicine, after Gerty Cori (awarded in 1947), the gap was filled by Rosalyn Yalow after 30 years (awarded in 1977). It is difficult to explain as to why such few women scientists were able to receive this recognition in science, especially when on revisiting history one is reminded of several notable women scientists who did contribute substantially to scientific research during these 60 years. The work of Nattic Maria Stevens proved a landmark in sex determination, as it was her work that led to conclusion that a combination of X and Y chromosomes in a particular pattern could determine the sex of an individual. Rosalin Franklin's outstanding research on X-ray diffraction provided an insight that DNA was a double helical structure, which laid down the foundation for molecular structure of DNA. Later, Watson and Crick, taking a clue from her X-ray diffraction patterns, proposed double helical DNA structure for which they were rewarded with the Nobel Prize in 1962. Maud Leonara Menten worked with Leonor Michaelis and deduced the Michaelis-Menten equation to understand enzyme kinetics. Ida Noddack, another well-known women scientist, was the first to propose the concept of nuclear fission. However, despite their outstanding contribution to innovative scientific research Nobel nomination eluded them.

Women Laureates and Challenges

An objective analysis of the possible reasons for such a disproportionate sex ratio among Nobel laureates indicates that more than one factor seem to have contributed to such a gap. Many commentators feel that it is more challenging for women scientists to seek recognition because most of the committees, including Nobel Prize screening committees, are male dominated, with very few women members. Some of the factors responsible for this low proportion of women Nobel Laureates are discussed below.

Research as a Career

One of the possible reasons believed to contribute to fewer women Nobel Laureates is a small number of women pursuing their higher education in research. However, the proportion of women pursuing research is much higher in developed countries in comparison to the developing ones [2]. Such a trend is attributed to the fact that a larger proportion of bright school girls does not take research as a career or change their career path after graduation in comparison to their male counterparts. Even if they continue their education in this field, most of them drop out in favor of non-research jobs. However, the trend has changed in the last 30 years and more women are taking up research as a career. Modern women have become career oriented and in the last few decades, there has been an increased participation of women in research. However, if we examine the ratio between women Nobel Laureates and women in the scientific profession, the gap has increased during the last few decades. This contradicts the earlier argument that fewer women Nobel laureates in science could be a consequence of a low proportion of women in research field. It has been found that the female researchers lack motivation in the absence of female role models [3, 4, 5, 6]. It is interesting to note that in a recent study, both male and female college students failed to list any women scientists or women Nobel laureates in a self-generated list of creative persons [7].

Social Responsibility

Gender discrimination in workplace or home continues to exist. Women are believed to take their responsibility more seriously towards the family than male counterparts and many of them prefer quitting their professional life in favor of household responsibilities [8]. Giving birth to children and raising them continue to be the prime responsibility of women even today [9]. Men on the other hand, giving minimal time to family, are seen as continuing to pursue research activity uninterrupted. Women who have been trying to balance the 2 roles, that is, homemaking and scientific research, have often ended up with breaks in their career, thus experiencing a retarded career growth in science because of juggling between family and work. Research being a time-consuming and long-term process, proves to be much more challenging for women in comparison to men due to the difficulties in maintaining family-work balance [10].

Moreover, gendered division of work exists for men and women. Women are supposed to be restricted to private sphere such as family and household, while men participate more in the public sphere getting better life and work opportunities. Women who crossed the line between the private and the public were once believed to lose femininity [11]. Rousseau, the author of “Emily,” promoted the complementarities theory, wherein men and women instead of being equals are considered to be complementary to each other, supported by the fact that there are biological differences between the 2 genders. The separation of men and women on the basis of private and public spheres results in a serious inequality of opportunities between men and women. The private and public spheres not only differ but also get hierarchized, resulting in men getting into an advantageous position due to their proximity to the public sphere. All scientific knowledge emanates from research organized in institutions situated in public sphere, while the knowledge produced in private sphere fails to enjoy the same credibility. Since women only had a private sphere outside universities to enhance their knowledge, their work was not valued [11].

In a study at the University of California, Berkeley, Mary Ann Goulden et al. [12] found that male and female postdocs without children were equally likely to decide against research career. However, female postdocs who either have become parents or plan to have children in future abandon research careers twice as often as men in comparable circumstances.

Gender Bias

No doubt the women have become more career oriented and society has also accepted the role of women in research; yet, even today, they do not receive an equal recognition for their achievements [13]. Women struggle to get enrolled under the advanced courses or PhD programs due to the reluctance of some faculty to mentor a women candidate, as women are more likely to get married during the research tenure thus disrupting the project at hand. Even though this is debatable, it is postulated that they tend to choose family in place of career and get distracted from scientific research [14]. Others argue that in the eastern world, encouragement from family to continue research is generally less for females when compared to males.

That gender discrimination continues to be a big issue in pursuit of science and research has been corroborated by Handelsman et al. [15] in her study, which confirmed that faculty members in Science belonging to both genders showed gender bias though at a subconscious level. In this study, the researchers asked more than one hundred Professors of Biology, Chemistry and Physics in 6 Universities of the United States to evaluate CVs of 2 fictitious College students, with a male and female name each, for a the job of laboratory manager. Interestingly, even though both the students had identical CVs, the Professors agreed to offer US$ 3,730 less per year to Jennifer than the other student named John. Further, they showed a greater willingness to be mentors for John in comparison to Jennifer [15]. These findings were further supported by another study conducted by the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 2010. Out of 1,300 respondents, 52% women reported to have encountered gender bias during their career, in comparison to a negligible proportion of men, that is, 2% [16].

It is therefore not surprising to find very few women at leadership positions, while most women settle for passive roles in research [6]. They are usually posted as part-time or adjunct faculty [17, 18]. Gender discrimination in academic rank promotion is also a significant contributor to less recognition of women in research, which is often argued as resulting from very few female chairpersons of academic committees [19].

More men hold top positions in the institutes that help them to establish their labs by providing support and resources [20]. This helps in increasing the productivity and increased publications of male scientists. On the other hand, due to fewer resources for women [21] publication index for women remains low, making it difficult for them to be nominated to the prestigious award.

However, there have been exceptions. For instance, Marie Curie was a woman par excellence and an exceptionally remarkable woman scientist who not only matched the standards set by most renowned male scientists in her research productivity and excellence but also raised her 2 daughters as a single mother after the untimely death of her husband. It is notable however that Madame Curie was not elected in French Academy of Sciences in 1911 even though she had great potential. She had to face rejection and criticism to such an extent that she decided not to try subsequently. Similarly, her daughter Irene Joliot-Curie applied for three times and was not selected even once, while on the other hand, her husband Jean Frederic Joliot Curie faced no problem to enter the Society. The gender discrimination in selection procedure proves to be arduous for women interested in pursuing scientific career and is generally believed as one of the important hurdles for them in achieving scientific excellence.

Gerty Cori, a Nobel Prize winner in Physiology or Medicine, too, was recognized by her institute only after she received the award. She attained the rank of a full professor at an age of 51, after receiving the Nobel Prize [22]. Anna Comstock, another pioneering woman scientist in the field of natural sciences, was not appointed as the assistant professor at Cornell and had to work as instructor with a lesser salary. The American Association of University Women has also reported the same trend for selection of women at higher positions at the Science institutes. Studies at the institutional level published in American Association of University Women Journal on the basis of number, rank and salaries of women at the institutes has documented no significant difference in the position of women along with a persistence of inferior treatment to women [23].

Studies show that although the work of several female researchers was admired by the academies and institutions, they were not hired at leadership positions raising questions about the equality label widely promoted by most world class universities. Maria Winkelmann, for example, in spite of her important discoveries and publications, which were published in high impact journals, could not move beyond an Assistant to her father and therefore continued to work at the same post even with her husband. Unfortunately, even after death of her husband she was denied a senior position in Akademie der Wissenschaften in Berlin, even though she had rich experience having worked with her husband. A male astronomer was employed on the position instead and she had to work under him, making her work less visible and noticeable. The situation did not change even for her children. All her three children studied astronomy, while only her son worked as an astronomer at Akademie der Wissenschaften, and the 2 daughters had to assist him [6].

A survey conducted in 1954–1955 revealed the condition of women in education according to which there were almost 3,600 women scientists, but most of them worked at the relatively less productive institutions. Again in 1960, the condition did not improve, as a study conducted at the 20 top universities showed that women representation in physics and biological sciences was almost negligible [24]. The share of women in institutions continued to be woefully low even in late nineties. A survey by NSF in 1999 and National Academy of Sciences supported the fact that women continued to work at lower ranks [25].

For each female candidate, there were several male candidates. In this competition, the members always elected the male candidate. The fear that an academy of science might lose its high status played an important role in this preference for male scientists [6]. It was observed that first women were elected as members of local academies, which were less prestigious than national academies. However, electing female members did not mean that the mechanism of excluding women disappeared. Rossiter wrote about new strategies to exclude women when their numbers increased. One strategy was the introduction of hierarchical differences between different members. Female newcomers, therefore, got lower positions as associate members as compared to older male members who were corporate members [26]. Another curious strategy consisted of excluding women from special meetings in the US academies by introducing “smokers” where cigars could be smoked. It was not appropriate for women to visit “smokers” because this could damage their reputation. Some men did not agree with this strategy and invited women to come to academy dinner meetings. Mary Whitney, for example, got a special invitation from the President of the American Astronomical Society to such a dinner, as he believed in gender equality [26]. Before 1950, only a few women were elected, while most of the female members were elected after 1970. However, this increase in female members does not make them less exceptional in these organizations, which contain a much larger proportion of men ranging from 85% (Turkey) to 99% (Spain). The history of the first female members clearly shows that the doors were opened to women only by progressive male members who tried to convince other male members of the scientific capabilities of some exceptional women, as can be seen in the case of Maria Winkelmann in Germany and Marie Curie in France. Once women became full members, they were able to open the doors to other women [1]. Only when the male-dominated environment within the academies changed and members realized that academies of sciences are not as gender neutral as they ought to be, the number of female members increased.

In earlier days, research was banned for women in US universities where women were allowed only as students or teachers and not as researchers [6]. The criteria to become a member of the National Academy of Sciences were such that no woman was eligible to enter the Academy. To be a member of this prestigious Academy, the person must have university education with a high rank in a University. Since only a few women were selected for full-time professorship, the percentage of women fulfilling the criteria was also low. Men's share as professors worldwide was 80–95% even in 1990. Thus, a vicious circle was formed wherein women could not pursue career in research as a result of which they were unable to get full-time professorship and eventually failed to fulfill the criteria for being members of the professional academy [27]. Moreover, women scientists had to face a biased attitude at the professional level, mainly from the successful and high ranking male scientists. For instance, grant applications for Swedish Medical Research Council for postdoctoral posts were subjected to biased judgment as reported in an article in Nature. Out of 52 applications submitted by women only 4 were funded as compared to 16 men out of 62 male applications [28].

In India, too, the participation of women at various academic levels is comparatively low. In a report published by INSA in year 2004, the number of women enrolled for higher studies in universities and women scientists recruited in major Government institutes like DBT, CSIR, ICMR, DAE, ICAR, IISc, JNU and University of Hyderabad were analyzed. It was found that although there was a rise in the number of women pursuing higher education, yet the gender gap persisted. The number of women employed in federal government organizations, both at scientific and technical levels, was below 15%. It was also reported that the participation of women even in advisory committees of institutes was very low [29].

Although the situation has changed, yet science continues to be gendered in that fewer women than men have been opting for science as a career. In a recent study, it has been confirmed that women tend to be outnumbered by men in science both in education as well as professions, not only in the developing but even in the most developed countries. The study was conducted by the Organization for Women in Science for the Developing World with the aid of a 2010 Elsevier Foundation grant [30].

Shielding Effect/Masking Effect

The lack of recognition of women in scientific world is another cause for reduced popularity of women scientists as nominators for Nobel Prizes [31]. The research work by women either remains shielded by their husbands working in the same field or by other male colleagues who are well recognized by virtue of being socially well networked in the society. Women's scientific contribution in Nobel Prize winning discoveries has therefore been generally overlooked. The fact that Lise Meitner who worked closely with Otto Hahn was completely neglected while Otto Hahn won the Nobel Prize remains a standing reminder of the situation.

It has also been argued that men married to women in the same academic career luckily obtained unacknowledged assistance from their wives [32]. Mileva Maric, wife of Albert Einstein, was a great physicist, but her efforts and contribution was negatively affected by her marriage as the credit was secured to Albert Einstein alone [33]. To take another illustration, Rosalind Franklin's work provided an indication suggesting DNA to be of the double helical structure but her work was masked by Watson and Crick, who received the Nobel Prize for giving the structure of DNA [34, 35]. X-ray diffraction pattern of B-DNA provided by Franklin clearly hinted towards the existence of DNA in the helical form, but the credit was given to male scientists 4 years after the death of Franklin. Another untold story was that of Jocelyn Bell Burner, who was an exceptionally bright graduate student and who discovered pulsars during her thesis. Her mentor received the Nobel Prize for the pulsar discovery, while Burner remained behind the scene. Such incidents of unacknowledged contribution have negative effect on female researchers. In cases where couples worked in the same fields, husbands tended to mask the talent of wives, who remained just informal advisors to their husbands as illustrated in the earlier case study. Marie Curie is believed to have understood this fact and thus published a single-author paper without collaboration with her husband at a very early stage of her career [36].

Likewise, the female astronomers could not develop their own projects and mostly wrote about the discoveries of the male astronomers, their work remained largely invisible. In England, Caroline Herschel worked as an assistant to her brother William, who worked as astronomer for the Royal Society in London [37]. She was allowed to work without any access to his telescope, which she could get only when William Herschel was abroad. She was the first woman who published her discoveries in the “Philosophical Transactions” of the Royal Society of London and was honored by the Royal Astronomical Society with a Gold Medal. In 1838, she was elected as a foreign member by the Royal Irish Academy when she was 88 years old. However, she never was elected as a member of the Royal Society in London [37].

These observations sufficiently affirm that female scientists have to live a very challenging life whether it pertains to obtaining admission to a degree course in a college, applying as a professor or as a member of a scientific academy. They have always failed to receive the recognition they deserved and hence always remained behind the scene. The condition was even worse before 1972 when the Equal Employment Opportunity Act had not been enacted. Before the implementation of this Act, state laws and policies as well as university rules and regulations proved to be great hurdles in the professional career of women. The university policies denied jobs to the wives of university employees. This implied that universities hiring a husband for a job excluded his wife to take up a job in the same university. In this way, if a husband and wife worked as a team, only the husband received compensation and recognition, while his wife just remained his shadow.

Science as a Gendered Profession

Julie Des Jardins in her book “The Madame Curie Complex” has presented a comparison between the lives of male and female scientists in order to understand the relationship between gender and science as a profession [38]. She studied the lives of Jane Goodall, Rosalind Franklin, Rosalyn Yalow, Barbara McClintock, Rachel Carson and the women actors of the Manhattan Project. She presented a comparison between the lives of these women scientists with those of Albert Einstein, Robert Oppenheimer and Enrico Fermi and showed how the working style, methods of work and work experience tend to vary between male and female scientists, primarily as a consequence of gender socialization. While women tend to have limited access to professional training and resources and suffer exclusion from professional and social networks largely dominated by men, they still have made enormous contributions to science and scientific knowledge. She demonstrates how science has a culture that is gendered in that the questions posed, the methods used and explanations offered, tend to vary between women and men scientists, indicating the gendered culture of science.

Helen Shen in an article entitled “Inequality quantified: Mind the Gender Gap” published in the Journal “Nature” March 6, 2013, has demonstrated that women scientists continue to face discrimination, unequal pay and funding disparities, leading to a gender inequality in science as a profession [39]. Sexism therefore continues to prevail, mainly placing women scientists at a receiving end. A study on doctoral students in Chemistry by the Royal Society of Chemistry in London in 2006 found that more than 70% of the 1st year women students indicated that they planned a career in research, but by the time they reached the 3rd year, only 37% were found to be pursuing that aim in comparison to 59% of the male students [40]. One explanation suggested for such a trend is that there are no role models for female researchers in science and they fail to find mentors for themselves. In one such study, female Chemistry researchers were found to be exhibiting lower self confidence in comparison to male researchers [41]. In a study in Spain, it has been found that it is a much more difficult task for women to secure a good career in science in comparison to men. In this study, men were found to be 2.5 times more likely to come up to the rank of full Professor in comparison with their women colleagues with comparable age, experience and publications [42].

Recognition Eludes Women Scientists

Recent research in the most developed countries of the world confirms that recognition still eludes women scientists despite their competence and caliber. In one such news released from Southern Methodist University in February 22, 2011, authors have shown that women scientists win fewer awards for their research, while they get more public recognition for service and teaching. Authors in this news release entitled “Gender Gap: Selection bias snubs scholarly achievements of female scientists,” on the basis of their analysis of data from 13 disciplinary societies, found that the proportion of female prize winners in 10 disciplinary societies was much lower in comparison to women full professors in each discipline. Research pointed out that the chances of a woman scientist winning the award increase if the selection committee has a woman member. However, most of the committees do not have women members. Moreover, the study found that the recommendation letters of women candidates use very stereotypical adjectives to describe the women scientists, that is, cooperative, dependable and so on. Therefore, women are seldom recognized for their professionalism and merit, pushing them down in career graph [43].

In one significant study, Wenneras and Wold in Sweden found that women applicants had to score 2.5 times higher on an index of publication impact than male applicants to be judged the same stereotyped perceptions towards women scientists have always made recognition much more difficult for them in comparison to their male colleagues [44]. Even in the case of Marie Curie, she was not recognized by Americans as a scientist but mainly as a benevolent woman, who was motivated like a good woman to help cancer patients. Jardins in her work built up a case for gendering the scientific culture.

A Ray of Hope/Changing Scenario

The patents and trademarks with the names of women are only 2.8% per year as recorded by US Patent and Trademark Office records in 1980s. There was a sudden rise in the proportion of women awardees in 1998 when 10.3% of the total US patents granted annually were received by women. Women Patentees included Katherine Holloway and Chen Zhao for protease inhibitors and Diane Pennica for the discovery of tissue plasminogen activator [45]. The rapid increase in participation of women scientists provided a hope that this percentage would increase continuously. Another US survey on a thousand researchers put forth names of 20 scientists under the age of 40, who have great scientific vision. Nine out of 20 selected persons were females, making women contribution almost 50% [45].

China has increased total share of GDP from 1.75 to 2.2% for research and development in its 12th five year plan [46]. These initiatives have included empowering women scientists as a part of their agenda. Loreal UNESCO was founded in 1998 to encourage women scientists by awarding elite scientists with “Women in Science” award. Each year, 5 women scientists are given this award for their contribution to science [47]. Therefore, more women have successfully entered the scientific arena as scientists and have begun to receive recognition. Jardins in her work [48] cited above has highlighted how some women scientists and professionals at the end of 20th century demolished the stereotyped image of women as “amateur scientists.” According to her, women increasingly received recognition as scientists and professionals in the postatomic age.

Share of Women in Nobel Nominations

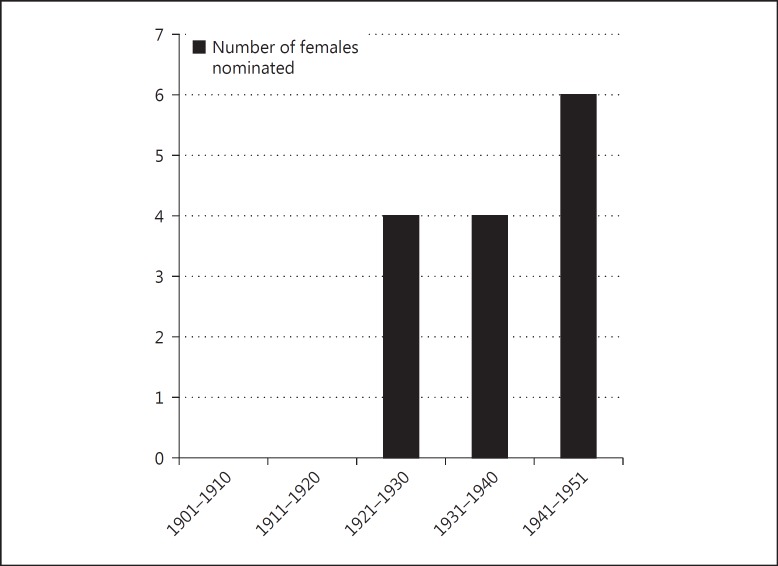

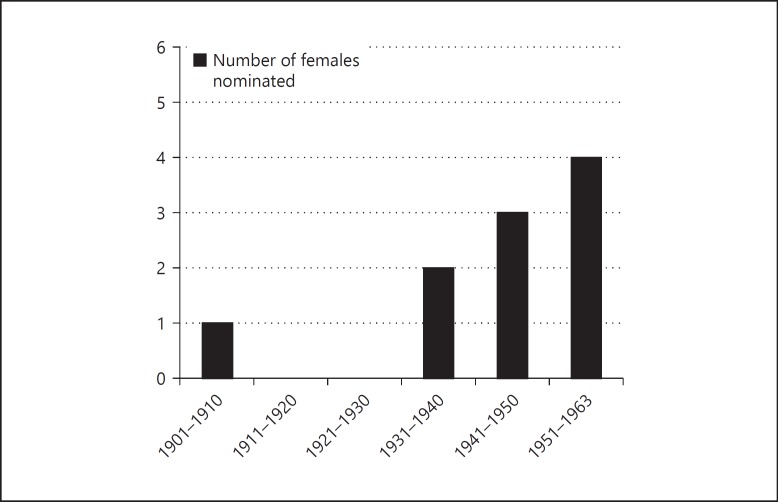

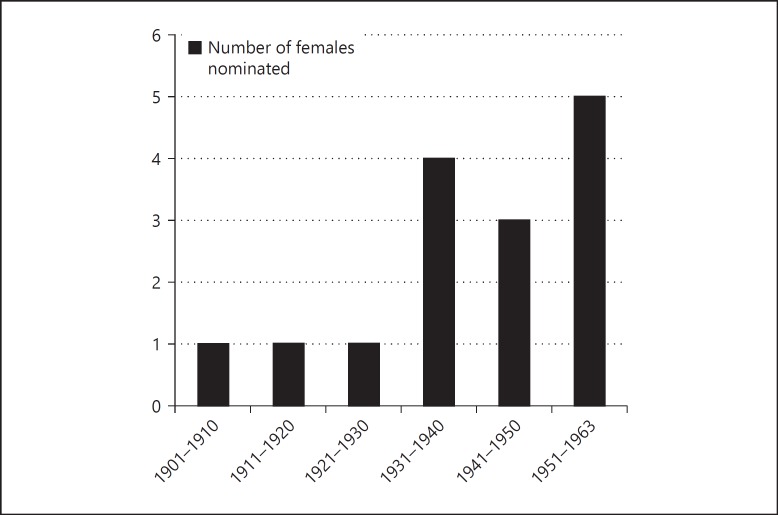

In the year 2014, the nomination archive was made public by the Nobel Prize committee. We examined the number of female scientists who were nominated in comparison to their male counterparts. We searched the nomination archive for Physics, Chemistry and Medicine to analyze the results (http://www.nobelprize.org/). Each year the total number of nominations, the number of women nominated and number of time each female scientist was nominated in a particular year in the field of Medicine (Table 1; Fig. 1), Physics (Table 2; Fig. 2) and Chemistry (Table 3; Fig. 3) was calculated. From the tables it can be seen that in all the three disciplines only 22 women scientists were nominated. Although many of these women were nominated more than once, only 5 of them viz. Marie Curie, Irene Joliot Curie, Gerty Cori, Maria Geoppert Mayer and Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin were able to receive the honour. Lise Mietner was nominated 27 times in Physics and 19 times in Chemistry but was not awarded the Nobel Prize. Gladys Dick (19 times nominated) and Helen Taussig (17 times nominated) are other 2 names, who despite nominations in the field of medicine, could not obtain the award.

Table 1.

Year-wise nominations for Nobel Prize in medicine from 1901 to 1951

| Medicine | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| year | nominations total | total females | name | number of times each female nominated | nominees |

| 1901 | 128 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1902 | 90 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1903 | 81 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1904 | 117 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1905 | 142 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1906 | 98 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1907 | 94 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1908 | 121 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1909 | 125 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1910 | 159 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1911 | 92 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1912 | 131 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1913 | 152 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1914 | 170 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1915 | 65 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1916 | 71 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1917 | 79 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1918 | 65 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1919 | 119 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1920 | 141 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1921 | 110 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1922 | 86 | 1 | Cecile Vogt | 3 | Emil Holmgren, G Bergmark, Robert Barany |

| 1923 | 141 | 2 | Maud Slye, | 1 | Albert Soiland |

| Cecile Vogt | 1 | Karl Kleist | |||

| 1924 | 102 | Nil | NA | ||

| 1925 | 155 | 1 | Gladys Dick | 5 | A Hewlett, Ludwig Hektoen, Arthue Elliott, W Howel, Wilfred Manwaring |

| 1926 | 102 | 2 | Cecile Vogt | 1 | Wilhelm Weygandt |

| Gladys Dick | 2 | Ulrich Friedemann, Fred Neufeld | |||

| 1927 | 108 | 1 | Gladys dick | 1 | Robert legge |

| 1928 | 147 | 2 | Cecile Vogt | 1 | E. Foerstor |

| Gladys Dick | 11 | Dallas Phemister, Archibald Church, Clifford Grulee, James Gill, R Woodyatt, Oliver Ormsby, Chas. Elliott, Thor Rothstein, Frederick Meuller, J Miller, James Herrick | |||

| 1929 | 139 | 1 | Cecile Vogt | 1 | Karl Kleist |

| 1930 | 121 | 2 | Cecile Vogt | 1 | A. Policard |

| Alice Bernheim | 1 | William Clarke | |||

| 1931 | 161 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1932 | 117 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1933 | 80 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1934 | 211 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1935 | 177 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1936 | 155 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1937 | 180 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1938 | 111 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1939 | 98 | 3 | Susan Smith | 1 | Osvaldo Polimanti |

| Marion Blankenhorn | 2 | Primo Dorello, Osvaldo Polimanti | |||

| Lady May Mellanby | 3 | Sir Charles Sherrington, Sir Frederick Hopkins, J Burn | |||

| 1940 | 58 | 1 | Olive smith | 1 | Frank Pemberton |

| 1941 | 68 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1942 | 50 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1943 | 28 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1944 | 23 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1945 | 47 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1946 | 86 | 2 | Gerty Cori; | 1 | Joseph Erlanger |

| M Ljubimova | 1 | Leon Orbeli | |||

| 1947 | 85 | 2 | Gerty Cori; | 1 | Joseph Erlanger |

| Helen Taussig | 1 | R Ghormley | |||

| 1948 | 148 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1949 | 103 | 1 | Helen Taussig | 2 | George Whipple, Corneille Heymans |

| 1950 | 121 | 2 | Cecile Vogt; | 1 | Franz Volhard |

| Helen Taussig | 7 | FV Brucke, CFW Illingworth, W Denk, H Kleinschmidt, H Hellner, P Plum, R Schoen | |||

| 1951 | 109 | 4 | Cecile Vogt; | 1 | P Vogel |

| Miriam Menkin, Helen | 1 | B Szabuniewicz | |||

| Tausig, | 7 | Neils Dungal, C De Garis, O Ullrich, G Morin, H Elbel, Heckenroth, G Jangle | |||

| Madge Macklin | * | * | |||

Nominator's name not mentioned on site.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of number of females nominated in the field of medicine.

Table 2.

Year-wise nominations for Nobel Prize in physics from 1901 to 1963

| Physics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| year | total nominations | number of females | name | times | nominator |

| 1901 | 30 | Nil | |||

| 1902 | 25 | 1 | Marie Curie | 2 | Gaston Darboux, Emil Warburg |

| 1903 | 35 | 1 | Marie Curie | 1 | Charles Bauchard |

| 1904 | 24 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1905 | 27 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1906 | 18 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1907 | 18 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1908 | 24 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1909 | 49 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1910 | 58 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1911 | 27 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1912 | 28 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1913 | 39 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1914 | 38 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1915 | 18 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1916 | 32 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1917 | 34 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1918 | 29 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1919 | 30 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1920 | 28 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1921 | 31 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1922 | 47 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1923 | 16 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1924 | 32 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1925 | 31 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1926 | 42 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1927 | 33 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1928 | 32 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1929 | 58 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1930 | 40 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1931 | 26 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1932 | 41 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1933 | 48 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1934 | 54 | 1 | Irene-joliot Curie | 9 | Reinhold Furth, Pierre Seve, Egon von Schweidler, Hantaro Nagaoka, Hans Thirring, Giulio Dalla Noce, Quirizo Majorana, Giorgio Todesco, Gustav Jager, Stefan Mayer |

| 1935 | 39 | 1 | Irene-joliot Curie | 6 | Prince Loius victor de-Broglie, David Enskog, Werner Heisenberg, Maurice de Broglie, Aime cotton, Neils Bohr |

| 1936 | 30 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1937 | 54 | 1 | Lise Meitner | 2 | Werner Heisenberg, Max von Laue |

| 1938 | 25 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1939 | 42 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1940 | 36 | 1 | Lise Meitner | 3 | Arthur Compton, James Franck, Dirk Coster |

| 1941 | 15 | 1 | Lise Meitner | 1 | James Franck |

| 1942 | 20 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1943 | 20 | 1 | Lise Meitner | 1 | James Franck |

| 1944 | 17 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1945 | 20 | 1 | Lise Meitner | 1 | Oskar Klein |

| 1946 | 26 | 1 | Lise Meitner | 5 | Max von Laue, Neils Bohr, Oskar Klein, Egil Hylleraas, James Franck |

| 1947 | 31 | 1 | Lise Meitner | 6 | Arthur Compton, Max Planck, Maurice de Broglie, Oskar Klein, Egil Hylleraas, Prince Victor de Broglie |

| 1948 | 35 | 1 | Lise Meitner | 2 | Herald Wergerland, Otto Hahn |

| 1949 | 53 | 1 | Lise Meitner | 1 | Georg Hettner |

| 1950 | 42 | 2 | Marietta Blau | 1 | Erwin Schrodinger; |

| Hertha Wambacher | 1 | Erwin Schrodinger | |||

| 1951 | 50 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1952 | 45 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1953 | 51 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1954 | 53 | 1 | Lise Meitner | 1 | Max Born |

| 1955 | 58 | 3 | Marrietta Blau | 1 | Hans Thirring |

| Lise Meitner | 1 | Georg Hettner | |||

| Maria Geoppert Mayer | 1 | Max born | |||

| 1956 | 72 | 4 | Marrietta Blau; | 1 | Erwin Schrodinger |

| Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin; | 1 | Sir Robert Robinson; | |||

| Maria Geoppert Mayer, | 6 | E Justi, M Kohler, H Urey, Karl Freudenberg, G Rathenau, James Franck | |||

| Lise Meitner | 1 | James Franck | |||

| 1957 | 65 | 2 | Dorothy Hodgkin, | 1 | John Bernal; |

| Maria G Mayer | 2 | James Franck, Karl Feudenberg | |||

| Marietta Blau | 1 | Erwin Schrödinger | |||

| 1958 | 50 | 1 | Maria GMayer | 1 | James Franck |

| 1959 | 62 | 3 | Lise Meitner, | 1 | J Rotblat; |

| Maria Geoppert Mayer, | 2 | Karl Freudenberd, Max Born | |||

| Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin | 1 | John Bernal | |||

| 1960 | 80 | 2 | Dorothy Crowfoot | 3 | H Lipson, W Bragg |

| Hodgkin, | Sir Cyril Norman Hinshelwood, | ||||

| Maria Geoppert Mayer | 4 | B Flowers, H Urey, Karl Freudenberg, Emilio Segrè | |||

| 1961 | 54 | 2 | Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin, | 2 | Sir Lawrence Bragg, John Bernal |

| Lise Meitner | 1 | J Rotblat | |||

| 1962 | 79 | 1 | Maria Geoppert Mayer | 6 | James Franck, M Kohler, Willard Frank Libby, H Maier Leibnitz, Lamek Hulthen, Torsten Gustafson |

| 1963 | 79 | 1 | Maria Geoppert Mayer | 2 | Torsten Gustafson, A de Shalit |

Fig. 2.

Distribution of number of females nominated in the field of physics.

Table 3.

Year-wise nominations for Nobel Prize in chemistry from 1901 to 1963

| Chemistry | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| year | total nominations | number of females | name | times | nominator |

| 1901 | 20 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1902 | 24 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1903 | 23 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1904 | 32 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1905 | 38 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1906 | 19 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1907 | 30 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1908 | 34 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1909 | 27 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1910 | 22 | 1 | Walthere Spring | 1 | Jean Krutwig |

| 1911 | 19 | 1 | Marie Curie | 2 | Gasten Darbaux, Svante Arrhenius |

| 1912 | 31 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1913 | 31 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1914 | 28 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1915 | 30 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1916 | 27 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1917 | 17 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1918 | 11 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1919 | 22 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1920 | 29 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1921 | 46 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1922 | 34 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1923 | 16 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1924 | 35 | 1 | Lise Meitner | 1 | Heinrich Goldschmidt |

| 1925 | 25 | 1 | Lise Meitner | 2 | Heinrich Goldschmidt, Kasimir Fajans |

| 1926 | 37 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1927 | 30 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1928 | 39 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1929 | 61 | 1 | Lise Meitner | 1 | Max Planck |

| 1930 | 29 | 1 | Lise Meitner | 1 | Max Planck |

| 1931 | 43 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1932 | 40 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1933 | 39 | 2 | Ida Noddack | 2 | Walther Nernst, Karl Wagner |

| Lise Meitner | 1 | Max Planck | |||

| 1934 | 41 | 1 | Lise Meitner | 1 | Max planck |

| 1935 | 50 | 2 | Irene joliot Curie | 3 | Ernest Lord Rutherford, Hans von Euler chelpin, Theodor Svedberg |

| Ida Noddack | 1 | Wolf Muller | |||

| 1936 | 38 | 1 | Lise Meitner | 2 | Adolf Deissmann, Max Planck |

| 1937 | 37 | 2 | Lise Meitner | 2 | Adolf Deissmann, Max Planck |

| Ida Noddack | 1 | Anton Skrabal | |||

| 1938 | 17 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1939 | 35 | 2 | Dorothy Wrinch; | 2 | Ernst Alexanderson, Irving Langmuir, Theodor Svedberg |

| Lise Meitner | 1 | ||||

| 1940 | 34 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1941 | 23 | 1 | Lise Meitner | 1 | Frans Jaeger |

| 1942 | 27 | 1 | Lise Meitner | 1 | Wilhelm Palmaer |

| 1943 | 18 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1944 | 37 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1945 | 24 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1946 | 33 | 1 | Lise Meitner | 1 | Kasimir Fajans |

| 1947 | 29 | 1 | lise Meitner | 2 | Niels Bohr, Nil Dhar |

| 1948 | 74 | 1 | lise Meitner | 2 | Oskar Klein, Niels Bohr |

| 1949 | 59 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1950 | 68 | 2 | Dorothy Hodgkin | 1 | Joseph Donnay |

| Therese Trefouel | 1 | Pauline-Ramart Lucas | |||

| 1951 | 55 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1952 | 67 | 1 | Marguerite Perry | 1 | Louis Hackspill |

| 1953 | 39 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1954 | 72 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1955 | 74 | Nil | NA | NA | NA |

| 1956 | 80 | 2 | Dorothy Hodgkin | 1 | Sir Robert Robinson |

| Joan folkes | 1 | John Northrop | |||

| 1957 | 95 | 2 | Marietta Blau | 1 | Erwin Schrodinger |

| Dorothy t Hodgkin | 4 | W Lipscomb, William Wardlaw, Robert Livingston, Leopold Ruzicka | |||

| 1958 | 85 | 2 | Marguerite Perry, | 1 | Georges Chaudron, |

| Maria G Mayer | 1 | Willis Lamb Jr. | |||

| 1959 | 69 | 1 | Dorothy Hodgkin | 3 | O Bastiansen, Johannes Bijvoet, C Martius |

| 1960 | 82 | 1 | Dorothy Hodgkin | 1 | Richard L Synge |

| 1961 | 80 | 2 | Dorothy Hodgkin, | 2 | Sir Robert Robinson, Sir Lawrence Bragg |

| Mireille Perry | 1 | Clement Courty | |||

| 1962 | 69 | 1 | Dorothy Hodgkin | 1 | Arne Westgren |

| 1963 | 88 | 1 | Dorothy Hodgkin | 3 | John Cowdery Kendrew, Max Ferdinand Perutz, W Bragg |

Fig. 3.

Distribution of number of females nominated in the field of chemistry.

Conclusions

The above discussion has brought out the perpetuation of gender disparities in the field of science, wherein it has been extremely challenging for women scientists to pursue a career in research, build a professional career as scientists, gain entry into the professional academic bodies of scientist and get rewarded for the professional excellence displayed by them. The reasons that can be attributed to such a trend are manifold. The binary between man and woman, projecting the woman as emotional, irrational and feminine, has been greatly responsible for such a state of affairs. Even the constitutional rights granted to women in employment and educational sectors have failed to bring gender equality in the field of science, mainly due to the strong conventional norms pushing them towards homemaking and domesticity. Even the secular and democratic culture of modern societies has not been able to dismantle the stereotypes placing women in subjugation to men both in private and public spheres. It is however all the more shocking to notice the gender discrimination in the profession of science, which itself is based on the principles of objectivity and secularism. Persistence of femininity and masculinity as the governing principles in every society has contributed immensely to the professional segregation of women into relatively low positions despite their caliber and talent. As Simon de Beauvoir has commented “she is the incidental, the inessential. He is the Subject; he is the Absolute - she is the Other.” This “otherness” necessarily implies that she is not equal to men and they cannot share the world and its fruits equally.

Generally, science is seen as a virtue that is said to be a necessary component of an emancipator project. People from all sections of society take science for granted for its rationality, secularism and fairness in objectivity. But we have all possible reasons to doubt its neutrality because it has got its gender bias with regard to Nobel Prizes. One should take cognizance of the fact that it is evident that the underrepresentation of women as scientists has not been a result of any biological handicap or natural incapacity, but this has largely been a consequence of the cultural norms eulogizing women as mothers and homemakers, instead of scientists or professionals. Women all over the world have been labeled as emotional, submissive and kind, while doing science has been considered a prerogative of men. There has been enormous change however due to feminist movement, rise of technology and increase in the number of women scientists over the years. That women too are capable of producing scientific knowledge and scientific innovations has finally been realized. The women's productivity and sincerity of purpose for research is no less valuable than that of men's and it is for the national and international societies to take upon themselves the task of not only encouraging science and research by rewarding women awardees but more importantly, by replacing the Nobel nomination procedure for women. This will go a long way in identifying the Nobel worthy scientists in the field for various spheres for which Nobel Foundation was set up.

Ethical Approval

None.

Disclosure Statement

Authors declare they have no competing financial interests. This article complies with International Committee of Medical Journal editor's uniform requirements for manuscript.

Funding Sources

The authors have no funding to declare.

Author Contribution

A.A. conceptualized the paper, S.M. drafted the paper, R.G., V.L.S., and S.V. edited it.

Acknowledgements

None.

References

- 1.Noordenbos G. Women in academies of sciences: from exclusion to exception. In Womens Stud Int Forum. 2002;25:127–137. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nussbaum MC. Women's education: a global challenge. Signs. 2004;29:325–355. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson CV. Women in science: in pursuit of female chemists. Nature. 2011;476:273–275. doi: 10.1038/476273a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buck GA, Clark VLP, Leslie-Pelecky D, Lu Y, Cerda-Lizarraga P. Examining the cognitive processes used by adolescent girls and women scientists in identifying science role models: a feminist approach. Sci Educ. 2008;92:688–707. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hackett G, Esposito D, O'Halloran MS. The relationship of role model influences to the career salience and educational plans of college women. J Vocat Behav. 1989;35:164–180. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Betz NE, Fitzgerald LF. The Career Psychology of Women. Academic Press. 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charyton C, Basham KM, Elliott JO. Examining gender with general creativity and preferences for creative persons in college students within the sciences and the arts. J Creat Behav. 2008;42:216–222. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charyton C, Elliott JO, Rahman MA, Woodard JL, DeDios S. Gender and science: women nobel laureates. J Creat Behav. 2011;45:203–214. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yabiku ST, Schlabach S. Social change and the relationships between education and employment. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2009;28:533–549. doi: 10.1007/s11113-008-9117-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emans SJ, Austin SB, Goodman E, Orr DP, Freeman R, Stoff D, Irwin CE. Improving adolescent and young adult health - training the next generation of physician scientists in transdisciplinary research. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schiebinger L. The Mind Has no Sex?: Women in the Origins of Modern Science. Harvard University Press. 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goulden M, Frasch K, Mason MA. Berkeley: Center for American Progress; 2009. Staying Competitive: Patching America's Leaky Pipeline in the Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koppel NB, Cano RM, Heyman SB, Kimmel H. Single Gender Programs: Do They Make a Difference? In Frontiers in Education. FIE 2003. 2003 33rd Annual (Vol. 1, pp. T4D-12). IEEE. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roe A. Women in science. Pers Guid J. 1996;44:784–787. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moss-Racusin CA, Dovidio JF, Brescoll VL, Graham MJ, Handelsman J. Science faculty's subtle gender biases favor male students. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:16474–16479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211286109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barriers for Women Scientists Survey Report, AAAS, 2010

- 17.Wolfinger NH, Mason MA, Goulden M. Problems in the pipeline: gender, marriage, and fertility in the ivory tower. J Higher Educ. 2008;79:388–405. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kulis S, Sicotte D, Collins S. More than a pipeline problem: labor supply constraints and gender stratification across academic science disciplines. Res High Educ. 2002;43:657–691. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cole JR, Zuckerman H. Marriage, motherhood and research performance in science. Sci Am. 1987;256:119–125. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0287-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie Y, Shauman KA, Shauman KA. No. 73. vol. 26. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2003. Women in Science: Career Processes and Outcomes; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ivie R, Tesfaye CL. Women in physics. Phys Today. 2012;65:47. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolfson AJ. One hundred years of American Women in biochemistry*. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2006;34:75–77. doi: 10.1002/bmb.2006.49403402075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levine S. Degrees of Equality: The American Association of University Women and the Challenge of Twentieth-Century Feminism. Temple University Press. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rossiter MW. Women Scientists in America: Before Affirmative Action, 1940–1972. JHU Press. 1988;(vol. 2) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Long JS., (ed) From Scarcity to Visibility: Gender Differences in the Careers of Doctoral Scientists and Engineers. National Academies Press. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossiter MW. Women Scientists in America: Struggles and Strategies to 1940. JHU Press. 1984;(vol. 1) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lie S, Malik L., (eds) World Yearbook of Education 1994: The Gender Gap in Higher Education. Routledge. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wenneras C, Wold A. Nepotism and Sexism in Peer-Review. Women, Science, and Technology. Routledge. 2001:pp 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marg BZ. Science Career for Indian Women: An Examination of Indian Women's Access to and Retention in Scientific Careers. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elan S. Pervasive Barriers Restrict Women's Participation in Science and Technology Fields Even in the Wealthiest Nations. Elsevier Connect. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lincoln AE, Pincus S, Koster JB, Leboy PS. The matilda effect in science: awards and prizes in the United States, 1990s and 2000s. Soc Stud Sci. 2012;42:307–320. doi: 10.1177/0306312711435830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kohlstedt SG. Sustaining gains: reflections on women in science and technology in 20th-century United States. NWSA J. 2004;16:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Troemel-Ploetz S. Mileva Einstein-Marić: the woman who did Einstein's mathematics. Index Censorship. 1990;19:33–36. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hubbard R. Science, power, gender: how DNA became the book of life. Signs. 2014:40. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maddox B. The double helix and the ‘wronged heroine’. Nature. 2003;421:407–408. doi: 10.1038/nature01399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pycior HM. Reaping the benefits of collaboration while avoiding its pitfalls: marie curie's rise to scientific prominence. Soc Stud Sci. 1993;23:301–323. doi: 10.1177/030631293023002003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alic M. Hypatia's Heritage: A History of Women in Science from Antiquity through the Nineteenth Century (No. 720) Beacon Press. 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Des Jardins J. The Madame Curie Complex: The Hidden History of Women in Science. Feminist Press at CUNY. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Des Jardins J. The Madame Curie Complex: The Hidden History of Women in Science. Feminist Press at CUNY. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen H. Inequality quantified: mind the gender gap. Nature. 2013;495:22–24. doi: 10.1038/495022a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Royal Society of Chemistry Change of Heart Career Intentions and the Chemistry PhD. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Newsome JL. The Chemistry PhD: The Impact on Women's Retention. Royal Society of Chemistry and the U.K. Resource Centre for Women in SET. 2008:p 38. [Google Scholar]

- 43.White Paper on the Position of Women in Science in Spain, UMYC

- 44.Southern Methodist University, News http://blog.smu.edu/research/2011/02/17/gender-gap-selection-bias-snubs-scholarly-achievements-of-female-scientists-with-fewer-awards-for-research. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wenneras C, Wold A. Nepotism and sexism in peer-review. Nature. 1997;387:341–343. doi: 10.1038/387341a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kurtz J. Mothers of invention: women in technology. Indiana Business Rev. 2003;78:1. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Casey J, Koleski K. Backgrounder: China's 12th Five-Year Plan. US-China Economic and Security Review Commission. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ip NY. Career development for women scientists in Asia. Neuron. 2011;70:1029–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]