Abstract

Background:

Breast cancer affects patients’ lives. Many breast cancer patients have problems with coping and they need support from their families. Family involvement based on the FOCUS program is designed to support breast cancer survivors within their families. The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of family involvement based on the FOCUS program on coping in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy in academic centers in Urmia in 2016.

Methods:

In this randomized controlled trial study, sixty breast cancer survivors were randomly assigned into intervention (N=30) and control (N=30) groups. The FOCUS program family-based intervention featured six sessions covering subject areas of family involvement, optimism, cancer coping, uncertainty reduction and symptom management. The instruments used were demographic and cancer coping questionnaires. Data were analyzed with SPSS 20 software.

Result:

The findings revealed a significant improvement in total cancer coping scores (t= -12/39, p<0.001), in all subscales including individual (t= -11/52, p<0.001), positive focus (t= -7/03, p<0.001), coping (t= -7/28, p<0.001), diversion (t= -11/76, p<0.001), planning (t=-4/91, p<0.001) and in interpersonal (t=-11/14, p<0.001). No significant changes were observed for the control group.

conclusion:

The results showed that family involvement based on the FOCUS program increases the ability to cope in breast cancer survivors.

Keywords: Breast cancer, coping, family support

Introduction

The breast cancer illness trajectory poses several challenges for women: adjusting to the initial news of having breast cancer; planning and recovering from any surgical management of the disease; questioning the most appropriate course of adjuvant therapy; overcoming the side-effects of treatment; awaiting word of being disease free or having a recurrence; and preparing for death in the case of progressive disease (Hack and Degner, 2004; Tabrizi, 2015; Sadeghi et al., 2016). Breast cancer patients need different coping skills to dealing with such psychological consequences. Coping strategies including but not limited to positive cognitive restructuring, wishful thinking, emotional expression, disease acceptance, increased religious practice, yoga, exercise and family and social support (Aldwin, 2007; Al-Azri et al., 2009; Tabrizi et al., 2016; Tabrizi et al., 2017). Support from significant others important for women in coping with the disease is the supportive role of a spouse and relatives. Women believed their family’s support is one of the important elements in their coping better with the disease and mentioned (Taleghani et al., 2006; Arora et al., 2007). If the family support is enough, it makes it easy to cope with the disease, but if not, it has a negative effect on coping (Henderson, 2003). Support from other family members may play a particularly salient role in coping with illness (Walker et al., 2006). Family-based interventions for patients with cancer have the potential to reduce marital and psychological distress and to promote their coping strategies (McMillan et al., 2006; Northouse et al., 2007; Northouse et al., 2010). Family-intervention programs based on FOCUS are designed to support patients and also their families and as well as to engage them.Studies show that patients are receiving FOCUS progmram, will have more positive results in coping and improvmet in their quality of life (8-10). FOCUS program contains the following steps:

F: Family involvement effectiveness, Family involvment is known as the most important factor in post-traumatic growth or post-traumatic stress by scientists. Family involvment encourages the couple to communicate with the patient and support her and work the problem in a group (Northouse et al., 2007; Northouse et al., 2010; Northouse et al., 2012).

O: Optimistic attitude, optimism and hope toward pleasant events in life can reduce depression, anxiety and mental and psychological disorders. Optimistic attitude will help the family by keeping hope and focusing on achieving short-term goals.(Northouse et al., 2007; Northouse et al., 2010; Northouse et al., 2012)

C: Coping effectiveness, the coping process emphasizes the techniques that reduce stress and effective adaptation strategies and healthy lifestyle behaviors. These strategies contain plans that were created in new conditions and will guide the patient to use appropriate solutions (Northouse et al., 2007; Northouse et al., 2010; Northouse et al., 2012).

U: Uncertainty reduction, The patients have a negative attitude and uncertainty toward the disease .Uncertainty reduction on diagnosis, treatment process or disease can affect the survival and health of the patient Considerations on uncertainty reduction provide some information about how to get information and live without doubt (Northouse et al., 2007; Northouse et al., 2010; Northouse et al., 2012).

S: symptoms management includes self-care strategies to control symptoms and experiences. These patients need help to cope with their disease and supply their disturbed needs in order to return to normal life (Akin et al., 2008).

In Iran, several studies have been done on the field of coping strategies in the breast cancer patients (Karimoi et al., 2006; Taleghani et al., 2006; Rohani et al., 2015). But it seems that what patients suffer more is how to adapt these coping methods with breast cancer and lack of knowledge about the effect of family support on coping process. So, further studies need be done on this field. Therefore, this study was designed to determine the effect of family intervention based on FOCUS program on coping with cancer in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy in medical-educational centers of Urmia in 2016.

Materials and Methods

Description of the Randomization Conditions

The double-blind randomized clinical trial (Registration ID in IRCT; IRCT2016052820778N16) was conducted (master’s degree thesis of midwifery student) in Urmia, in North West of Iran. Eligible subjects were: aged 20 to 60, understanding the Persian language, having breast cancer and chemotherapy in Stage 1, 2 and 3 and having no other cancer and have mastectomy. Women with general health disorders (screened by General Health Questionnaire).

Breast cancer patients who consented to participate were randomly assigned into 2 groups by using odd and even numbers.

Sample size was calculated based on the results of a study conducted by Behzadipour et al was estimated that 26 subjects were needed in each group and 20 percent attrition was added to the sample (n=30) (Behzadipour, 2013).

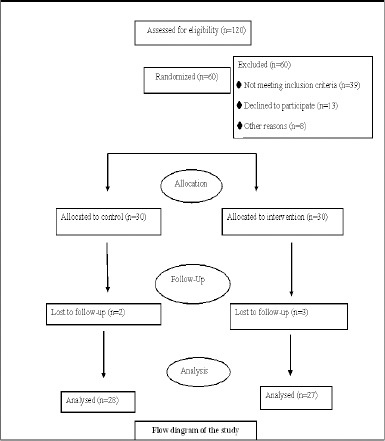

As illustrated in the CONSORT flowchart (Figure 1) 120 breast cancer patients and their families were invented for the study, 60participants were excluded because of not meeting inclusion criteria (n=39), declining to participate (n=13) and other reasons (n=7). Finally, 60 participants were included in the study and randomized, 30 allocated to the intervention and 30 to the control group. Finally there were 3 lost cases in the intervention group and 2 lost in the control group.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of the Study

Measures

Demographic characteristic

A brief questionnaire was completed to obtain demographic information, such as age, type of surgery, stage of disease, marital status, education level, economic status and living with whom was designed by the researcher.

General Health Questionnaire (GHQ 28)

General Health Questionnaire (GHQ 28) was used to screen the subjects’ mental health. The GHQ28 consists of four subscales including somatic symptoms (items 1-7), anxiety/insomnia (items 8-14), social dysfunction (items 15-21) and severe depression (items 22-28). All items are responded on a 4-pointLikert scale of none, mild, moderate, and severe which are scored from zero to three. The score 23 or above was the cut-off point for probability of having a mental health disorder (Goldberg, 1992). Accordingly, women who obtained scores >23 were excluded from the study. The Persian version of GHQ 28 questionnaire was validated by Yaghoubi, as cited in Ozgoli et al., (2009) and its sensitivity and specificity were calculated to be 86.5 and 82, respectively.

The Cancer Coping Questionnaire

This questionnaire consists of 21 items rated on a 4-point scale ranging from one (not at all) to four (very often). It is divided into two sections: Total Individual Scale (Items 1–14), which includes coping (Items 2, 6, 7, 11, 12), positive Focus (Items 1, 9, 14), diversion (Items 3, 4, 8) and planning (Items 5, 10, 13); and Interpersonal Scale (Items 15–21).(Moorey et al., 2003). In the study of Atef-vahid in Iranian cancer patients, the Chronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.92.(Atef-Vahid et al., 2011) This questionnaire was delivered to 10 experts in the field of cancer to evaluate content validity. The content validity ratio (CVR) was 37/75 and content validity index (CVI) was 82/32 which are acceptable.

Ethical Considerations

The research protocol was approved by the institutional review board and the ethics committee of the Urmia University of Medical Sciences (Ir.umsu.rec.1395.109). Participants were provided with detailed information about the study and were assured that confidentiality would be maintained at all times. Written consent was obtained prior to data collection.

Intervention

The intervention includes individual and group consultation for family, in 6 sessions with 5-6 patients and one active family member. Every session lasted 1.5-2 hours in each week. Through the sessions, first, the researcher discussed every simple item in FOCUS and explained all items. Every patient received a notebook to record their thoughts, feelings and all experiences toward the coping strategies. Also, they were encouraged to keep records of the assignments that were supposed to be done at home. In last 20 minutes, the researcher provided a summary about the discussed issues. It should be noted that, due to ethical reasons, after intervention, there were two more sessions for people in control groups.

| Session content | Meeting’s subject |

|---|---|

| -Introducing and making friends and doing pre-test and asking about the present condition and problems of the patient. - Providing strategies for the patients to receive physical, mental and emotional family support. - Emphasizing the family role in improvement of the current condition and coping with cancer. |

Session one Family involvement effectiveness |

| Optimistic attitude and its influence on coping- Being positive by challenging negative thoughts Increasing positive excitements. Emphasizing daily use of optimistic strategies by patients and their family.- |

Session two Optimistic attitude |

| -Discussing best ways to havecalm in order to reduce stress and providng solutions to tolerate problems. - Providing ways to cope with cancer effect on appearance and family and normal life. - Introducing successful scenarios in society on coping with cancer |

Session three Coping effectiveness |

| - Encouraging patients to talk about the ambiguities and ask their questions about the disease. - Inspiring patients to ask doctors their questions and trying to make clear the ambiguities about the challenges through group discussions. - Sharing patients and their family’s concerns about treatment expenses and providing solutions to receive financial support as: joining association of cancer patients, receiving help from a social worker. |

Session four Uncertainty reduction |

| - Providing solutions on self-care to control the symptom, side effects of the treatment, communicating effectively with therapeutic team to control the symptoms - debating about ways to manage concerns and feelings and sharing participant’s experiences and methods to control stress like relaxing muscles and body |

Session five Symptoms management |

| - Increasing family involvement by FOCUS - Reaching to a conclusion using previously discussed issues - Performing post-test. |

Session six |

Analytical statistics were used to analyze the data and in order to analyze hypothesis, t test was applied. Data was analyzed by SPSS 20 software.

Results

The results showed that demographic and clinical characteristics characters of the women with breast cancer in both groups of intervention and control were similar (p>0.05) (Table 1). The average age for women with breast cancer in intervention group is 47/03±7/73 and in control group 46/16±7/59(t=0/45 and p-value=0/65).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Breast Cancer Patients

| variable | Intervention | Control | Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Educational Status | Under Diploma | 18 | 60 | 19 | 63/3 | X2=0/5 |

| Diploma | 6 | 20 | 7 | 23/3 | Df=2 | |

| Collegiate | 6 | 20 | 4 | 13/3 | P* =0/77 | |

| Marital Status | Married | 29 | 96/7 | 26 | 86/7 | Pfisher=0/41 |

| Divorced | 1 | 3/3 | 2 | 06/7 | ||

| Widow | 0 | 0 | 2 | 06/7 | ||

| Economic Status | No money problem | 10 | 33/3 | 8 | 26/7 | Pfisher=0/92 |

| Fair | 17 | 56/7 | 19 | 63/3 | ||

| Not enough | 3 | 10 | 3 | 10 | ||

| Type Of Surgery | Total Mastectomy | 24 | 80 | 26 | 86/7 | X2=0/48 |

| Df=1 | ||||||

| Partial Mastectomy | 6 | 20 | 4 | 13/3 | P=0/48 | |

| Life Status | With Husband and Children | 29 | 96/7 | 27 | 90 | Pfisher= 0/74 |

| Parent | 1 | 3/3 | 1 | 03/3 | ||

| Alone | 0 | 0 | 1 | 03/3 | ||

| Stage | I | 6 | 20 | 4 | 13/3 | X2=0/78 |

| II | 15 | 50 | 16 | 53/3 | Df=2 | |

| II | 9 | 30 | 10 | 33/3 | P=0/48 | |

Regarding the effects of intervention our findings revealed a significant promotion in total cancer coping scores (t=-12/39, p<0.001) and in it’s all subscales including individual (t=-11/52, p<0.001), positive focus (t=-7/03, p<0.001), coping(t=-7/28, p<0.001), diversion (t=-11/76, p<0.001), planning (t=-4/91, p<0.001) and in interpersonal subscale (t=-11/14, p<0.001). But there was no significant difference in control group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Changes in Coping Scores in Intervention and Control Group

| variable | Mean | SD | (t) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | intervention | Pre-test | 35/81 | 8/78 | -11/52 | <0/001 |

| Post-test | 42/11 | 6/97 | ||||

| control | Pre-test | 35/32 | 8/21 | -1/65 | 0/10 | |

| Post-test | 35/82 | 8/18 | ||||

| Coping | intervention | Pre-test | 12/70 | 3/59 | -7/28 | <0/001 |

| Post-test | 14/66 | 2/88 | ||||

| control | Pre-test | 12/64 | 3/09 | -0/54 | 0/58 | |

| Post-test | 12/78 | 3/27 | ||||

| Positive focus | intervention | Pre-test | 8/29 | 221 | -7/03 | <0/001 |

| Post-test | 9/81 | 1/61 | ||||

| control | Pre-test | 7/82 | 249 | -1/46 | 0/88 | |

| Post-test | 7/96 | 237 | ||||

| Diversion | intervention | Pre-test | 7/14 | 1/91 | 11/76 | <0/001 |

| Post-test | 9 | 1/59 | ||||

| control | Pre-test | 7/14 | 1/81 | -1/50 | 0/14 | |

| Post-test | 7/50 | 215 | ||||

| Planning | intervention | Pre-test | 7/66 | 214 | -4/91 | <0/001 |

| Post-test | 8/62 | 1/92 | ||||

| control | Pre-test | 7/60 | 214 | 0/17 | 0/86 | |

| Post-test | 7/47 | 3/19 | ||||

| Interpersonal | intervention | Pre-test | 19/59 | 4/18 | -11/14 | <0/001 |

| Post-test | 22/70 | 3/14 | ||||

| control | Pre-test | 19/71 | 4/44 | -1 | 0/32 | |

| Post-test | 19/96 | 4/13 | ||||

| Total scores of coping | intervention | Pre-test | 55/40 | 12/43 | -12/39 | >0/001 |

| Post-test | 64/81 | 9/53 | ||||

| control | Pre-test | 55/03 | 12/20 | -1/65 | 0/10 | |

| Post-test | 55/78 | 11/87 |

Discussion

The current resaerch was designrd and conducted on family involvement effect based on FOCUS program on coping with breast cancer in women who were under chemotherapy in medical-educational centers in Urmia in 2016. The results on coping with cancer and individual and interpersonal dimensions of the qustionnaire, indicated significant promotion in intervention group compared to the control group. In the other word the present study highlited the family members role in facilitating cancer coping process. Regarding coping subscale the result of our study mentioned that perciving family members support is essential to cope with cancer.

Indead the present study demonstrated the crucial role of family involvement in coping with breast cancer. Other studies confirm the results of the present study about the crucial role of family members as an influential factor to facilitate the coping process in these women (Taleghani et al., 2006; Alcalar et al., 2012). In this line the results of other study conducted by Manne et al., (2014) showed a significant relation between lack of husband’s support and low degree of adaptation with cancer. Other studies pointed out the more the family support, the more recovery probability and adaption (Arora et al., 2007; Shoaa kazemi, 2014).

Also Taleghani et al., (2006) in their study revealed that, patients and their family members require family support to cope with cancer. Further, Alcalar et al., (2012) showed that in breast cancer patients there is a significant association among depression level, disappointment, anxiety and weak coping.

One of the individual scales of the questionnaire is “positive focus”, which emphasizing positive making plans for the future life, the skills of concentration on positive aspects of life, positive thought, thinking about advantages of life base on the items described in this section of the questionnaire. In this view there was a significant improvement in the intervention group compared to control group who received only routine care. In agreement with the present study David et al., (2006) demonstrated that the degree of optimism and pessimism is directly related to anxiety during surgery in patients with breast cancer. Positive thinking and optimism are associated with high expectations of success and increase motivation. Besides, optimist people show affective coping behavior and higher social communications, higher flexibility, psycho-somatic wellbeing in comparison to pessimist people. Optimist thinking lead to increase in person’s ability to overcome obstacles and create other choices to obtain the goals (Scheier et al., 1994; Shaheen et al., 2014). Women with breast cancer experience less positive excitements and are reluctant toward happiness, they rarely present their positive feelings. Based on a relationship between emotions and affection with immune system of the body function, the immune system of these people acts weakly so makes them more vulnerable to disease (Hodges and Winstanley, 2012). Friedman et al ., (2006) illustrated that encouraging positive expectations and facilitating social support help the women with breast cancer to overcome stressful process of the diagnosis and have a better treatment period.

Thought diversion is an adaptation strategy that causes to better adapting of people with life changes. In this respect, the families have declared that they have avoided talking about their cancer. The researchers have tried to convince patients into doing new and amusing activities in order not to think about their disease. In concurrence to our study Devries et al., (2014) pictured that women with cancer use excitement based strategies to overcome the fear of recurring their cancer. In various studies thought diversion is emphasized.’ Thought diversion’ is to think about anything but the present problem (Czerw et al., 2016; Sadruddin et al., 2017).

Planning for the future based on the questionnaire’s items includes planning about the most priority life issues, enjoying leisure time and planning to do the rest of the chores, the results showed that there is significant difference after intervention in intervention group in comparison to control group; in other words, family involvement could empower the women to make plans for the future. Patients with cancer are losing their hope about future and it seems that challenging nature of the disease leads to an ambiguity situation about future. Hope allows human beings to overcome stressful situations and enable him to make a steady effort to achieve his goal (Folkman, 2010). Zhang et al., (2010) displayed that there is a significant relationship between the degree of coping and hope in patients with breast cancer. Demiling et al., (2006) showed that the least common types of coping mechanisms used by people with cancer are acceptance and planning, and the highest rates are denial and escape. That rejection is correlated with greater anxiety, depression and cancer-related concerns, which leads to the inability of a person to plan for the future.

On the interpersonal dimension, based on the items in the questionnaire, including asking for help from the spouse and relatives, talking with the spouse about the negative effects of the illness, discussing with husband about the disease, considering the disease as a family problem, talking to husband and relatives about better managing of the chores in order to reduce stress, the study results indicate a significant increase in this dimension in the intervention group after intervention compared to control group. In this area, we tried to create some information about tangible and instrumental support of family, emotional support and personal information support by family for the patients. In accordance with the present study, Deckham et al., (2015) conducted a study, applying FOCUS intervention program on patients with breast cancer and their nurses at home. The results showed physical and emotional improvement in life quality of the patients. Another research carried out by Northouse et al., (2010) showed that family support leads to improvement in life quality in cancer patients.

The current study’s results show that family support of breast cancer patients can be a positive factor in order to recover and increase patient’s ability to cope with current condition. The results showed that these skills and abilities can be taught and with enough time and effort, they can be added to coping process framework of the patient. Based on the effect of various factors on patient’s ability in coping with cancer, such as her friends and the relation of patient with them, designing similar involvements are recommended.

In conclusion, the results of our study depicted that family members involvement in order to create support for women with breast cancer play an instructive and illuminating role for enabling women to apply for positive strategies in order to obtain promotion in cancer coping. The results showed that these skills and abilities can be taught with spending time and being patient encounter with persons with cancer and even they can be included to coping process framework of the patients. Based on the effective and practical roles of family members in regard to obtain the sufficient cancer coping in patients, designing and including these critical programs in cancer care services are recommended.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

Acknowledgements

This research is a midwifery Master’s Degree thesis with ethic code of IR.umsu.rec.1395.109 at Urmia University of Medical Sciences. Special thanks to research principal of the University and all cancer patients and their families who took part in this research.

References

- 1.Al-Azri M, Al-Awisi H, Al-Moundhri M. Coping with a diagnosis of breast cancer-literature review and implications for developing countries. Breast J. 2009;15:615–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2009.00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alcalar N, Ozkan S, Kucucuk S, et al. Association of coping style, cognitive errors and cancer-related variables with depression in women treated for breast cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2012;42:940–7. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hys119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aldwin CM. Stress, coping, and development:An integrative perspective, Guilford Press. Clin Soc Rew. 2007;15:210–11. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arora NK, Finney Rutten LJ, Gustafson DH, et al. Perceived helpfulness and impact of social support provided by family, friends, and health care providers to women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2007;16:474–86. doi: 10.1002/pon.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atef-Vahid M-K, Nasr-Esfahani M, Esfeedvajani MS, et al. Quality of life, religious attitude and cancer coping in a sample of Iranian patients with cancer. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16:928–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behzadipour S SM, Keshavarzi F, Farzad V, Naziri G. The effectiveness of cognitive behavioral stress management intervention on quality of life and coping strategies in women with breast cancer. J Methods psychol Mod. 2013;3:29–46. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Czerw A, Religioni U, Deptała A. Assessment of pain, acceptance of illness, adjustment to life with cancer and coping strategies in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer. 2016;23:654–61. doi: 10.1007/s12282-015-0620-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.David D, Montgomery GH, Bovbjerg DH. Relations between coping responses and optimism–pessimism in predicting anticipatory psychological distress in surgical breast cancer patients. Personal Individ Differ. 2006;40:203–13. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Vries J, Den Oudsten BL, Jacobs PM, et al. How breast cancer survivors cope with fear of recurrence:a focus group study. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:705–12. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2025-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deimling GT, Wagner LJ, Bowman KF, et al. Coping among older-adult, long-term cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2006;15:143–59. doi: 10.1002/pon.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dockham B, Schafenacker A, Yoon H, et al. Implementation of a psychoeducational program for cancer survivors and family caregivers at a cancer support community affiliate:A pilot effectiveness study. Cancer Nurs. 2015;39:169–80. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folkman S. Stress, coping, and hope. Psychooncology. 2010;19:901–8. doi: 10.1002/pon.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedman LC, Kalidas M, Elledge R, et al. Optimism, social support and psychosocial functioning among women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15:595–603. doi: 10.1002/pon.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg LR. The development of markers for the Big-Five factor structure. Psychol Assess. 1992;4:26. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hack TF, Degner LF. Coping responses following breast cancer diagnosis predict psychological adjustment three years later. Psychooncology. 2004;13:235–47. doi: 10.1002/pon.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henderson P. African American women coping with breast cancer:a qualitative analysis. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003;30:641–7. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.641-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodges K, Winstanley S. Effects of optimism, social support, fighting spirit, cancer worry and internal health locus of control on positive affect in cancer survivors:a path analysis. Stress Health. 2012;28:408–15. doi: 10.1002/smi.2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karimoi M, Pourdehghan M, Faghihzadeh S, et al. The eeffects of group counseling on symptom scales of life quality in patients with breast cancer treated by chemotherapy. J Kermanshah Univ Med Sci. 2006;10:44–52. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manne S, Kashy DA, Siegel S, et al. Unsupportive partner behaviors, social-cognitive processing, and psychological outcomes in couples coping with early stage breast cancer. J Fam Psychol. 2014;28:214. doi: 10.1037/a0036053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McMillan SC, Small BJ, Weitzner M, et al. Impact of coping skills intervention with family caregivers of hospice patients with cancer. Cancer. 2006;106:214–22. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moorey S, Frampton M, Greer S. The cancer coping questionnaire:A self-rating scale for measuring the impact of adjuvant psychological therapy on coping behaviour. Psychooncology. 2003;12:331–44. doi: 10.1002/pon.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Schafenacker AM, et al. The impact of caregiving on the psychological well-being of family caregivers and cancer patients. Seminars in oncology nursing. Elsevier. 2012:236–45. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, et al. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients:meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:317–39. doi: 10.3322/caac.20081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Northouse LL, Mood DW, Schafenacker A, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a family intervention for prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Cancer. 2007;110:2809–18. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozgoli G, Selselei EA, Mojab F, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of Ginkgo biloba L. in treatment of premenstrual syndrome. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:845–51. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rohani C, Abedi H-A, Omranipour R, et al. Health-related quality of life and the predictive role of sense of coherence, spirituality and religious coping in a sample of Iranian women with breast cancer:a prospective study with comparative design. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:40. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0229-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sadeghi E, Gozali N, Moghaddam Tabrizi F. Effects of energy conservation strategies on cancer related fatigue and health promotion lifestyle in breast cancersurvivors:a Randomized control trial. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:4783–90. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2016.17.10.4783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sadruddin S, Jan R, Jabbar AA, et al. Patient education and mind diversion in supportive care. Br J Nurs. 2017;26:14–9. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2017.26.10.S14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem):a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67:1063. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaheen N, Andleeb S, Ahmad S, et al. Effect of optimism on psychological stress in breast cancer women. J Soc Sci. 2014;8:84–90. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shoaa kazemi M HS, Saadati M. Relation between family social support &coping strategies in recovery breast cancer. Iran J Breast Dis. 2014;6:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tabrizi FM. Health promoting behavior and influencing factors in Iranian breast cancer survivors. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:1729–36. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.5.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tabrizi FM, Alizadeh S, Barjasteh S. Managerial self-efficacy for chemotherapy-related symptoms and related risk factors in women with breast cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18:1549–53. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.6.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tabrizi FM, Radfar M, Taei Z. Effects of supportive-expressive discussion groups on loneliness, hope and quality of life in breast cancer survivors:a randomized control trial. Psychooncology. 2016;25:1057–63. doi: 10.1002/pon.4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taleghani F, Yekta ZP, Nasrabadi AN. Coping with breast cancer in newly diagnosed Iranian women. J Adv Nurs. 2006;54:265–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03808_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walker MS, Zona DM, Fisher EB. Depressive symptoms after lung cancer surgery:Their relation to coping style and social support. Psychooncology. 2006;15:684–93. doi: 10.1002/pon.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang J, Gao W, Wang P, et al. Relationships among hope, coping style and social support for breast cancer patients. Chin Med J. 2010;123:2331–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]