Abstract

The abuse potential of gabapentin is well documented; with gabapentin having been noted as an agent highly sought after for use in potentiating opioids. When combined with opioids, the risk of respiratory depression and opioid-related mortality increases significantly. In the US, gabapentin was approved by the Food and Drug Administration as a non-controlled substance. To date, and in spite of empirical evidence suggestive of diversion and abuse with opioids, gabapentin remains a non-controlled substance at the federal level. This has forced individual US states and jurisdictions – often significantly impacted by the opioid epidemic – to forge ahead with legislative initiatives designed to reclassify and/or monitor the use of gabapentin. Since August 1, 2016, 14 of 51 US states and jurisdictions have either implemented legislative mandates requiring pharmacovigilance programs, amended rules and regulations, are in the throes of crafting policy, or are in the midst of gathering additional data for decision making. This fragmented geographic approach yields only a modest benefit in combating the abuse of gabapentin and/or the national opioid epidemic. Herein, we report state-by-state efforts to enhance pharmacovigilance and call for a re-evaluation of the schedule status of gabapentin at the federal level, and design and implementation of a national pharmacovigilance program.

Keywords: gabapentin, prescription drug abuse, opioids, pharmacovigilance, health policy

Introduction

In the USA, ~2.1 million individuals have been diagnosed with opioid use disorder defined as abuse with illicit and/or prescription medications,1 thereby resulting in significant morbidity, mortality, and an increase in state and federal health service expenditures.2 In light of these events, federal and state regulatory agencies and legislative bodies have mandated, enacted, and implemented harm reduction and abuse mitigation strategies pertaining to opioids, such as limiting prescription days’ supply, quantity dispensed, and dose;3 support for development of abuse-deterrent opioids;4 and requiring use of Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs).5 Given tighter regulation, it has become somewhat more difficult for persons with opioid use disorder to obtain opioids in the absence of a legitimate medical need.6 Gabapentin, a structural analog of gamma-aminobutyric acid that is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for post-herpetic neuralgia and as an adjunctive therapy for partial seizures, has been deemed an opportunistic drug of abuse, due to low cost, classification as a non-controlled substance,7 and increasing rates of on- and off-label prescribing8 attributable to clinician’s desire for an alternative to opioids for pain management.9–11

In the first national (US) assessment of the prevalence of gabapentin abuse, gabapentin displayed similar abuse patterns to medications previously identified as demonstrating abuse potential and was either prescribed or diverted at average daily dosages exceeding that of the FDA maximum daily recommendation by threefold.12 While these findings are of concern, the most pressing issue is the abuse of gabapentin as an adjunct to opioids to potentiate “opioid high”. This has been subjectively reported by patients, though was briefly documented in the literature in two small reports, one small survey examining abuse of methadone13 and one case report of buprenorphine/naloxone abuse.14

In a subsequent national (US) assessment of medical harm resulting from gabapentin and opioid co-abuse, ~24% of patients with sustained co-prescription of gabapentin and opioids had at least three prescription claims exceeding established dosage thresholds; as compared to the 3% and 8% of patients prescribed gabapentin or opioids alone, respectively.15 This is of particular concern, as abuse of gabapentin in concert with opioids has been associated with a fourfold increased risk of respiratory depression,15 the primary cause of death in opioid-related overdose.16 Research suggests that gabapentin, at doses exceeding 900 mg, may lead to as much as a 60% increase in the odds of opioid-related death relative to abuse of opioids alone.17

The abuse potential of gabapentin has stimulated an interest in regulatory review in jurisdictions experiencing high rates of opioid addiction. In the State of West Virginia, a state experiencing a high rate of opioid addiction,18 Federal Senator Manchin announced his support in December 2017 for an inquiry into the role of gabapentin in relationship to opioid abuse.19 Subsequently, Dr Gottlieb, Commissioner of the US FDA, announced the agency would pursue an investigation of the abuse potential of gabapentin.20 That said, other federal agencies, inclusive of the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have yet to publicly express a viewpoint or initiate an inquiry.

Given the increasing social and economic consequences of the opioid epidemic, legislatures and regulatory bodies in US states and jurisdictions have taken, and are initiating, actions to mitigate gabapentin abuse, either alone or in concert with opioids. Herein, we present the status of these state-level initiatives as of March 1, 2018 and call for federal reclassification of gabapentin as a controlled substance and a national framework for pharmacovigilance.

Materials and methods

This inquiry focused on the regulatory and pharmacovigilance policies of US states and jurisdictions and was primarily conducted via searches of the world-wide-web via the following terms, either alone or in concert: prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP); gabapentin; Schedule-V; controlled substance; “drug of concern”. Two researchers verified the information obtained via world-wide-web. In the absence of results collected via the above methodology, or the need for further clarification, telephone and email inquiries were conducted with officials from state PDMPs and State Boards of Pharmacy. The specific information sought was whether gabapentin was a controlled substance at the state level and/or a mandatory reportable medication to state-level PDMP. This search was performed through March 1, 2018.

Results

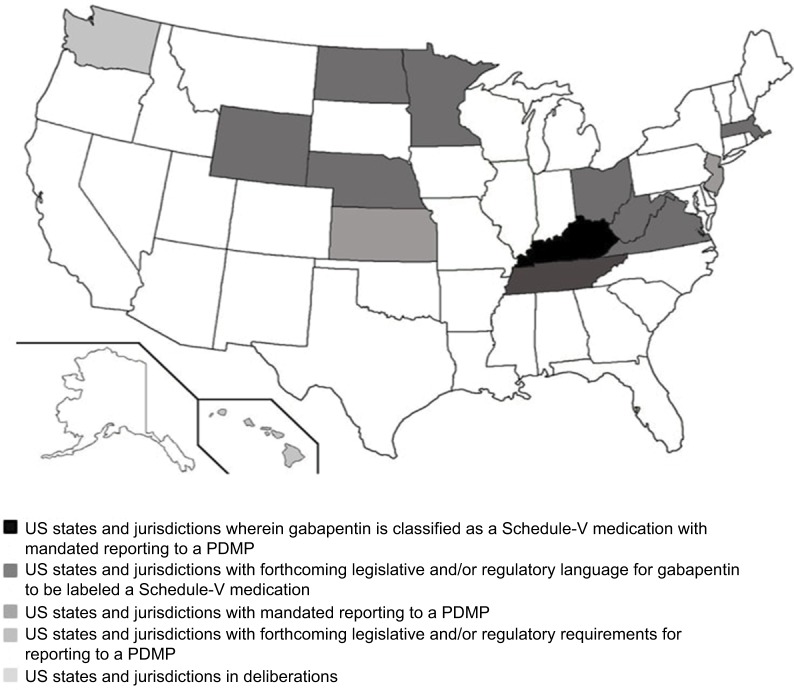

Figure 1 and Table 1 depict a visual and tabulated summary of findings in the following categories: 1) US states and jurisdictions wherein gabapentin is classified as a Schedule-V medication with mandated reporting to a PDMP; 2) US states and jurisdictions with mandated reporting to a PDMP; 3) US states and jurisdictions with forthcoming legislative and/or regulatory requirements for reporting to a PDMP; 4) US states and jurisdictions with forthcoming legislative and/or regulatory language for gabapentin to be labeled a Schedule-V medication; and (5) US states and jurisdictions in deliberations. Table 2 provides a state-by-state tabulation of when the above information was collected and the contact.

Figure 1.

Gabapentin regulation, legislation, and monitoring requirements within each US state as of March 1, 2018.

Abbreviation: PDMP, Prescription Drug Monitoring Program.

Table 1.

US state-level regulation, legislation, and monitoring requirements for gabapentin as of March 1, 2018

| Status of gabapentin oversight | State(s) | Effective date and/or status |

|---|---|---|

| US states and jurisdictions wherein gabapentin is classified as a Schedule-V medication with mandated reporting to a PDMP | Kentucky | July 1, 2017 |

|

| ||

| US states and jurisdictions with forthcoming legislative and/or regulatory language for gabapentin to be labeled a Schedule-V medication | Tennessee | Schedule-V proposal scheduled for review on February 27–28, 2018. If approved, effective July 1, 2018 |

|

| ||

| US states and jurisdictions with mandated reporting to a PDMP | Minnesota | August 1, 2016 |

| Ohio | December 1, 2016 | |

| Virginia | February 23, 2017 | |

| Wyoming | May 17, 2017 | |

| West Virginia | July 7, 2017 | |

| Massachusetts | August 1, 2017 | |

| North Dakota | August 1, 2017 | |

| Nebraskaa | January 1, 2018 | |

|

| ||

| US states and jurisdictions with forthcoming legislative and/or regulatory requirements for reporting to a PDMP | Kansas | “Drug of concern” and PDMP proposal out for public comment until March 8, 2018. If approved, effective date TBD |

| New Jersey | PDMP reporting proposal out for public comment until March 3, 2018. If approved, effective date is TBD | |

|

| ||

| US states and jurisdictions in deliberations | Washington | Interprofessional review underway |

| Hawaii | Monitoring national trends | |

Note:

The State of Nebraska: all prescription medications reported to PDMP regardless of scheduling status.

Abbreviations: PDMP, Prescription Drug Monitoring Program; TBD, to be determined.

Table 2.

US state-level information source

| State | Timeframe of data collection: November 30, 2017 through March 1, 2018 |

|---|---|

| AL | Nancy Bishop, RPh; November 30, 2017 email correspondence |

| State Pharmacy Director, Alabama Department of Public Health | |

| AK | Alaska’s Prescription Drug Monitoring Program, Controlled Substance Legislative Update – August 2017; available at: https://www.commerce.alaska.gov/web/portals/5/pub/PDMP_EffectiveDates_08.2017.pdf |

| AZ | Douglas Skvarla, RPh; December 4, 2017 email correspondence |

| Controlled Substance Prescription Monitoring Program Director, Arizona State Board of Pharmacy | |

| AR | Denise Robertson; December 5, 2017 email correspondence |

| Prescription Monitoring Program Administrator, Arkansas Department of Health | |

| CA | Tina Farales; December 5, 2017 email correspondence |

| Controlled Substance Utilization Review and Evaluation System Program Manager, California Department of Justice | |

| CO | Mark O-Neill, RPh; December 5, 2017 email correspondence |

| Program Manager, Colorado Prescription Drug Monitoring Program | |

| CT | Operator; January 11, 2018 telephone correspondence |

| Connecticut Prescription Monitoring Program Assistance Line | |

| DE | Jason Slavoski, PharmD; December 7, 2017 email correspondence |

| Pharmacist Administrator, State of Delaware | |

| FL | Rebecca Poston, RPh, MHL; December 6, 2017 email correspondence |

| Program Manager, Florida Prescription Drug Monitoring Program | |

| GA | Kimberly Emm, Attorney; December 6, 2017 email correspondence |

| Attorney, Georgia Board of Dentistry & Pharmacy | |

| HI | Hawaii Board of Pharmacy meeting minutes; available at: https://cca.hawaii.gov/pvl/files/2013/06/170817-min.doc.pdf47 and https://cca.hawaii.gov/pvl/files/2013/06/170921-min.doc.pdf48 |

| ID | Teresa Anderson; December 12, 2017 email correspondence |

| Program Information Coordinator, Idaho Board of Pharmacy | |

| IL | Illinois General Assembly, Section 316. Prescription Monitoring Program; available at: http://www.ilga.gov/legislation/ilcs/fulltext.asp?DocName=072005700K31649 |

| IN | Indiana Professional Licensing Agency, Laws & Regulations; available at: http://www.in.gov/pla/inspect/2442.htm50 |

| IA | Terry Witkowski; December 5, 2017 email correspondence |

| Executive Officer, Iowa Board of Pharmacy | |

| KS | Kansas State Board of Pharmacy Proposed Regulatory Changes to KAR 68-21-7; available at: http://pharmacy.ks.gov/docs/default-source/statues-regulations/kar-68-21-7.pdf?sfvrsn=4da4a601_051 |

| KY | Important Notice: Gabapentin Becomes a Schedule 5 Controlled Substance in Kentucky; available at: http://chfs.ky.gov/NR/rdonlyres/92D10F1A-8842-4E6D-B9D2-935741E2926E/0/KentuckyGabapentinFactSheet.pdf52 |

| LA | Joseph Fontenot, RPh; December 10, 2017 email correspondence |

| Assistant Executive Director, Louisiana Board of Pharmacy | |

| ME | Operator; December 13, 2017 telephone correspondence |

| Maine Department of Health and Human Service, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Assistance Line | |

| MD | Kate Jackson, MPH; December 6, 2017 email correspondence |

| Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Coordinator, Maryland Department of Health | |

| MA | Massachusetts PMP Data Submission Dispenser Guide; available at: https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2017/09/12/pmp-data-submission-guide.pdf53 |

| MI | Operator; December 7, 2017 email correspondence |

| Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs, Bureau of Professional Licensing, Drug Monitoring Section, Michigan Automated Prescription System | |

| MN | Minnesota PMP Data Uploaders; available at: http://pmp.pharmacy.state.mn.us/pmp-data-uploaders.html54 |

| MS | Dana Crenshaw; December 6, 2017 email correspondence |

| Prescription Monitoring Program Director, Mississippi Board of Pharmacy | |

| MO | Operator; January 17, 2018 telephone correspondence |

| Missouri Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs Assistance Line | |

| MT | John Douglas, RPh; December 7, 2017 email correspondence |

| Inspector, Montana Board of Pharmacy | |

| NE | Balick R. Nebraska pharmacists will report all prescriptions to state PDMP. Pharmacy Today. 2017 Nov;23(11):50–51.55 |

| NV | Yenh Long, PharmD, BCACP; January 10, 2018 telephone correspondence |

| Program Administrator, Nevada Board of Pharmacy | |

| NH | Operator; January 17, 2018 telephone correspondence |

| New Hampshire Office of Professional Licensure and Certification Main Telephone Line | |

| NJ | New Jersey Division of Consumer Affairs, Rule Proposal; available at: http://www.njconsumeraffairs.gov/Proposals/Pages/directorsoffice-01022018-proposal.aspx56 |

| NM | Maria Gonzales; January 3, 2018 email correspondence |

| Prescription Monitoring Program Manager, New Mexico Board of Pharmacy | |

| NY | New York State Department of Health, Internet System for Tracking Over-Prescribing – Prescription Monitoring Program; available at: https://www.health.ny.gov/professionals/narcotic/prescription_monitoring/57 |

| NC | John Womble; January 16, 2018 email correspondence |

| Program Consultant, Controlled Substances Reporting System, North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services | |

| ND | North Dakota Board of Pharmacy Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Law; available at: https://www.nodakpharmacy.com/pdfs/PDMPlaws.pdf58 |

| OH | Ohio Laws and Rules, Dangerous drug monitoring; available at: http://codes.ohio.gov/oac/4729-37-1259 |

| OK | Brian Veazey; December 7, 2017 email correspondence |

| Agent in Charge, Oklahoma Bureau of Narcotics & Dangerous Drugs Control | |

| OR | Drew Simpson; December 11, 2017 email correspondence |

| Program Coordinator, Prescription Drug Monitoring Program, Public Health Division | |

| PA | Carrie Thomas, PhD; January 16, 2018 email correspondence |

| Epidemiologist, Prescription Drug Monitoring Program, Pennsylvania Department of Health | |

| RI | Peter Ragosta, RPh; December 11, 2017 email correspondence |

| Chief Administrative Officer, Rhode Island Board of Pharmacy, Division of Customer Services | |

| SC | Christie Frick, RPh; December 7, 2017 email correspondence |

| Director of Prescription Monitoring Program, South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control, Bureau of Drug Control | |

| SD | Kari Shanard-Koenders, RPh; December 7, 2017 email correspondence |

| Executive Director, South Dakota Board of Pharmacy | |

| TN | Tennessee House Bill 1832; available at: http://www.capitol.tn.gov/Bills/110/Bill/HB1832.pdf60 |

| TX | Allison Benz, RPh, MS; December 7, 2017 email correspondence |

| Executive Director/Secretary, Texas State Board of Pharmacy | |

| UT | David Furlong; December 11, 2017 email correspondence |

| Chief Investigator, Utah Division of Occupational and Professional Licensing, Utah Department of Commerce | |

| VT | Carrie Phillips, MS, PharmD; January 17, 2018 email correspondence |

| Executive Officer, Vermont Pharmacy Board, Office of Professional Regulation | |

| VA | Virginia House Bill 2164; available at: http://leg1.state.va.us/cgi-bin/legp504.exe?171+ful+HB2164ER+pdf61 |

| WA | Washington State Pharmacy Quality Assurance Commission Meeting Minutes, December 15, 2017; available at: https://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/Mtgs/2017/20171215-MN-PH.pdf62 and https://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/Mtgs/2017/20171215-AG-PH.pdf63 |

| WDC | Tadessa Nichols, Program Specialist; January 25, 2018 email correspondence |

| Pharmaceutical Control Division, Department of Health, Health Regulation & Licensing Administration | |

| WV | West Virginia PDMP PowerPoint; available at: http://qioprogram.org/sites/default/files/editors/141/WV_PDMP_Recording_508.pdf64 |

| WI | Nicole Anspach; December 14, 2017 email correspondence |

| Public Information Officer, Wisconsin Department of Safety and Professional Services | |

| WY | Wyoming Prescription Drug Monitoring Program, available at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B8cDfZ_Wrtc8bFBUWGd5VDdJYU0/view65 |

Abbreviations: BCACP, Board Certified Ambulatory Care Pharmacist; KAR, Kansas Administrative Regulation; MHL, Master’s in Health Law; MPH, Master of Public Health; MS, master-level degree; PDMP, Prescription Drug Monitoring Program; PharmD, Doctor of Pharmacy; PhD, doctoral-level degree; PMP, Prescription Monitoring Program; RPh, registered pharmacist.

Schedule-V controlled substance and mandated reporting to PDMP

The State of Kentucky is, and to date, remains, the only state to have reclassified gabapentin as a Schedule-V controlled substance.21 Effective July 1, 2017, the prescribing of gabapentin is limited to authorized practitioners, defined as practitioners registered with the US DEA.21 Thus, mid-level practitioners, specifically, Physician Assistants, are no longer eligible to prescribe gabapentin, as they are not permitted to prescribe controlled substances in the State of Kentucky.21 Advanced Practice Registered Nurses may prescribe gabapentin if they obtain a DEA license.21 Furthermore, gabapentin prescriptions are now limited to a maximum of five authorized refills, or a 6 months’ supply, after the issuance date of the original prescription, which corresponds with the restrictions placed on all Schedule-V medications in the State of Kentucky.21 The dispensing of gabapentin is subject to reporting to the State of Kentucky All Schedule Prescription Electronic Reporting system, the PDMP in the State of Kentucky.21

Mandated reporting to PDMP

To date, the most common state-level legislative and/or regulatory approach to monitor the dispensing of gabapentin is to require the reporting of said event to a PDMP. Eight states (Minnesota,22 Ohio,23 Virginia,24 Wyoming,25 West Virginia,26 Massachusetts,27 North Dakota,28 and Nebraska29) have implemented this policy (effective dates ranging from August 1, 2016 in Minnesota22 to January 1, 2018 in Nebraska).29 Monitoring of dispensing will facilitate uniform collection and subsequent analysis of data, with the potential to detect and mitigate outliers in the prescribing of gabapentin.

Forthcoming changes to mandate reporting to PDMP

The State of Kansas has motioned to amend the list of “drugs of concern”, thereby clearing the way to add gabapentin.30 The proposal is out for public comment, with a public hearing scheduled for March 8, 2018.30 If approved, all listed medications will be monitored through the State of Kansas Prescription Monitoring Program (Kansas Tracking and Reporting of Controlled Substances Program, more commonly known as K-TRACS), the PDMP of the State of Kansas.30 Similarly, the State of New Jersey has motioned to amend the rules pertaining to the State of New Jersey Prescription Monitoring Program, the PDMP of the State of New Jersey.31 Presently, this proposal is out for public comment through March 3, 2018, with an effective date to be determined.31

Forthcoming changes to convert gabapentin to Schedule-V controlled substance

In the State of Tennessee, a legislative bill was filed in January 2018 that motioned to procedurally add gabapentin to the compendium of Schedule-V medications.32 This bill is scheduled for review by the State of Tennessee Senate Judiciary Committee on February 27, 2018 and by the State of Tennessee Criminal Justice Committee on February 28, 2018.32 If approved by both bodies, the proposed change will be effective as of July 1, 2018.32 By nature of becoming a Schedule-V medication, gabapentin refills and days’ supply limits would be restricted in the State of Tennessee in the same manner as is mandated in the State of Kentucky.32 The dispensing of gabapentin would be subject to reporting to the State of Tennessee Controlled Substance Monitoring Database, which is the PDMP of the State of Tennessee.32 The legislation provides that in the State of Tennessee, both Physician Assistants and Advanced Practice Registered Nurses would be able to prescribe a Schedule-V medication so long as the practitioner holds a DEA license.32

Current deliberation

In the State of Washington, the Pharmacy Quality Assurance Commission was provided with data on abuse and overdose of gabapentin by the State of Washington Poison Center on December 15, 2017.33 This presentation was at the behest of the State of Washington Department of Health, the entity responsible for the State of Washington PDMP.34 Members of the Pharmacy Quality Assurance Commission motioned to consult with the State of Washington Commissions or Boards of Medicine, Nursing, Dentistry, Osteopathic Medicine, and Podiatry prior to reaching a decision.33 In the State of Hawaii, the State Board of Pharmacy issued a report on national trends in state-level gabapentin rules and regulations in both August 201735 and September 2017.36 To date, no further action has been taken.

Limitations

The information included herein is time sensitive and, thus, should be interpreted as a national assessment of gabapentin policy as of March 1, 2018. Given that gabapentin abuse has just recently received national attention from the FDA,20 it is likely that states will begin to implement more stringent criteria in the near future pending federal oversight.

Discussion and conclusion

The US is in the throes of an opioid epidemic, and while the national focus on opioid addiction is important from a social, economic, and public health perspective, it has overshadowed the growing diversion and concomitant abuse of other prescription medications used to potentiate an “opioid high”.2,6 Gabapentin presents as an opportunistic prescription drug of abuse, given its relatively low cost and non-schedule status at the federal level.15

In the absence of federal efforts to reclassify gabapentin as a controlled substance, a small number of US states have implemented a number of regulatory approaches to mitigate diversion and abuse. Primary strategies include the reclassification of gabapentin as a controlled substance and mandating the reporting of the prescribing and/or dispensing of gabapentin to a state-level PDMP.37 These efforts are progressive both nationally and globally, as gabapentin is not classified as a controlled substance in Europe38 despite previous European reports of gabapentin abuse,39–42 nor is it a controlled substance in Australia or Canada.43,44

While state-level efforts to combat the diversion and abuse of gabapentin, and thus the opioid epidemic, are to be commended, such efforts are not a substitute for a strategic national approach. Given the growing empirical evidence surrounding both the diversion and abuse of gabapentin, we call for reclassification as a controlled substance at the federal level and implementation of a national pharmacovigilance program.45,46 Additionally, future research is needed to identify the degree of regulatory oversight needed to effectively detect and mitigate gabapentin abuse.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.National Institute on Drug Abuse America’s addiction to opioids: heroin and prescription drug abuse. [Accessed March 16, 2018]. Available from: https://www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/legislative-activities/testimony-to-congress/2016/amer-icas-addiction-to-opioids-heroin-prescription-drug-abuse.

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services The opioid epidemic: by the numbers. [Accessed February 7, 2018]. Available from: https://www.accesskent.com/Health/SubAbuse/pdfs/DrugOD_USOpioidEpidemic_factsheet.pdf.

- 3.National Conference of State Legislatures Prescribing policies: states confront opioid overdose epidemic. [Accessed February 7, 2018]. Available from: www.ncsl.org/research/health/prescribing-policies-states-confront-opioid-overdose-epidemic.aspx.

- 4.U.S. Food and Drug Administration FDA takes important step to increase the development of, and access to, abuse-deterrent opioids. [Accessed February 8, 2018]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAn-nouncements/ucm492237.htm.

- 5.Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Training and Technical Assistance Center Prescription drug monitoring frequently asked questions (FAQ) [Accessed February 8, 2018]. Available from: www.pdmpassist.org/content/prescription-drug-monitoring-frequently-asked-questions-faq.

- 6.Raji MA, Kuo YF, Adhikari D, Baillargeon J, Goodwin JS. Decline in opioid prescribing after federal rescheduling of hydrocodone products. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2018;27(5):513–519. doi: 10.1002/pds.4376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peckham AM, Fairman KA, Sclar DA. Policies to mitigate non-medical use of prescription medications: how should emerging evidence of gabapentin misuse be addressed? Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2018;17(5):519–523. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2017.1390081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.QuintilesIMS Institute Medicines use and spending in the U.S. [Accessed February 7, 2018]. Available from: https://morningconsult.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/IMS-Institute-US-Drug-Spending-2015.pdf.

- 9.Goodman CW, Brett AS. Gabapentin and pregabalin for pain – is increased prescribing a cause for concern? N Engl J Med. 2017;377(5):411–414. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1704633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fukada C, Kohler JC, Boon H, Austin Z, Krahn M. Prescribing gabapentin off label: perspectives from psychiatry, pain and neurology specialists. Can Pharm J. 2012;145(6):280–284. doi: 10.3821/145.6.cpj280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mack A. Examination of the evidence for off-label use of gabapentin. J Manag Care Pharm. 2003;9(6):559–568. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2003.9.6.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peckham AM, Fairman KA, Sclar DA. Prevalence of gabapentin abuse: comparison with agents with known abuse potential in a commercially insured US population. Clin Drug Investig. 2017;37(8):763–773. doi: 10.1007/s40261-017-0530-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baird CR, Fox P, Colvin LA. Gabapentinoid abuse in order to potentiate the effect of methadone: a survey among substance misusers. Eur Addict Res. 2014;20(3):115–118. doi: 10.1159/000355268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reeves RR, Ladner ME. Potentiation of the effect of buprenorphine/naloxone with gabapentin or quetiapine. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(6):691. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13111526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peckham AM, Fairman KA, Sclar DA. All-cause and drug-related medical events associated with overuse of gabapentin and/or opioid medications: a retrospective cohort analysis of a commercially insured US population. Drug Saf. 2018;41(2):213–228. doi: 10.1007/s40264-017-0595-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization Information sheet on opioid overdose. [Accessed February 23, 2018]. Available from: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/information-sheet/en/

- 17.Gomes T, Juurlink DN, Antoniou T, et al. Gabapentin, opioids, and the risk of opioid-related death: a population-based nested case-control study. PLoS Med. 2017;14(10):e1002396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holden W. Manchin asks FDA, DEA to consider rescheduling gabapentin. [Accessed February 23, 2018]. Available from: http://www.register-herald.com/news/manchin-asks-fda-dea-to-consider-rescheduling-gabapentin/article_442fa04b-7ed9-5bf8-8d19-b5440e9c278b.html.

- 19.The Fiscal Times How West Virginia became ground zero for the opioid epidemic. [Accessed March 16, 2018]. Available from: http://www.thefiscaltimes.com/2016/12/19/How-West-Virginia-Became-Ground-Zero-Opioid-Epidemic.

- 20.U.S. Food and Drug Administration Remarks by Dr. Gottlieb at the public workshop on strategies for promoting the safe use and appropriate prescribing of prescription opioids. [Accessed February 23, 2018]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Speeches/ucm596893.htm.

- 21.Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services Important notice: gabapentin becomes a schedule 5 controlled substance in Kentucky. [Accessed February 26, 2018]. Available from: http://chfs.ky.gov/NR/rdonlyres/92D10F1A-8842-4E6D-B9D2-935741E2926E/0/KentuckyGabapentinFactSheet.pdf.

- 22.Minnesota Prescription Monitoring Program PMP data uploaders. [Accessed February 26, 2018]. Available from: http://pmp.pharmacy.state.mn.us/pmp-data-uploaders.html.

- 23.LAWriter Ohio Laws and Rules. 4729-37-12 Dangerous drug monitoring. [Accessed February 26, 2018]. Available from: http://codes.ohio.gov/oac/4729-37-12.

- 24.Virginia Acts of Assembly Chapter. §54.1-345.1 of the Code of Virginia. [Accessed February 26, 2018]. Available from: http://leg1.state.va.us/cgi-bin/legp504.exe?171+ful+HB2164ER+pdf.

- 25.Controlled Substance Act Chapter 8 – Prescription Drug Monitoring Program. [Accessed February 26, 2018]. Available from: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B8cDfZ_Wrtc8bFBUWGd5VDdJYU0/view.

- 26.Quality Improvement Organizations West Virginia Prescription Drug Monitoring Program. [Accessed February 26, 2018]. Available from: http://qioprogram.org/sites/default/files/editors/141/WV_PDMP_Recording_508.pdf.

- 27.Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Department of Public Health PMP AWARxE Prescription Monitoring Program. [Accessed February 26, 2018]. Available from: https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2017/09/12/pmp-data-submission-guide.pdf.

- 28.North Dakota Board of Pharmacy Chapter 19-03.5 Prescription Drug Monitoring Program. [Accessed February 26, 2018]. Available from: https://www.nodakpharmacy.com/pdfs/PDMPlaws.pdf.

- 29.Balick R. Nebraska pharmacists will report all prescriptions to state PDMP. Pharm Today. 2017;23(11):50–51. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kansas State Board of Pharmacy Proposed Regulatory Changes to KAR 68-21-7. [Accessed February 26, 2018]. Available from: http://pharmacy.ks.gov/docs/default-source/statues-regulations/kar-68-21-7.pdf?sfvrsn=4da4a601_0.

- 31.New Jersey Division of Consumer Affairs Rule Proposal. [Accessed February 26, 2018]. Available from: http://www.njconsumeraffairs.gov/Proposals/Pages/directorsof-fice-01022018-proposal.aspx.

- 32.The General Assembly of the State of Tennessee House Bill 1832. [Accessed February 26, 2018]. Available from: http://www.capitol.tn.gov/Bills/110/Bill/HB1832.pdf.

- 33.State of Washington Department of Health Washington State Pharmacy Quality Assurance Commission Meeting Minutes December 15, 2017; [Accessed February 26, 2018]. Available from: https://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/Mtgs/2017/20171215-MN-PH.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 34.State of Washington Department of Health Washington State Pharmacy Quality Assurance Amended Business Meeting Agenda December 15, 2017; [Accessed February 26, 2018]. Available from: https://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/Mtgs/2017/20171215-AG-PH.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hawaii Board of Pharmacy Minutes of Meeting August 17, 2017; [Accessed February 26, 2018]. Available from: https://cca.hawaii.gov/pvl/files/2013/06/170817-min.doc.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hawaii Board of Pharmacy Minutes of Meeting September 21, 2017. [Accessed February 26, 2018]. Available from: https://cca.hawaii.gov/pvl/files/2013/06/170921-min.doc.pdf.

- 37.U.S. Department of Justice, Drug Enforcement Administration, Diversion Control Division State Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs. [Accessed February 27, 2018]. Available from: https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/faq/rx_monitor.htm.

- 38.European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction Substances and classifications table (31/10/2008) [Accessed May 14, 2018]. Available from: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/html.cfm/index5733EN.html.

- 39.Gabapentin and pregabalin: abuse and addiction. Prescrire Int. 2012;21(128):152–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kapil V, Green JL, Le Lait MC, Wood DM, Dargan PI. Misuse of the γ-aminobutyric acid analogues baclofen, gabapentin and pregabalin in the UK. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78(1):190–191. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Häkkinen M, Vuori E, Kalso E, Gergov M, Ojanperä I. Profiles of pregabalin and gabapentin abuse by postmortem toxicology. Forensic Sci Int. 2014;241:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2014.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chiappini S, Schifano F. A decade of gabapentinoid misuse: an analysis of the European medicines agency’s ‘suspected adverse drug reactions’ database. CNS Drugs. 2016;30(7):647–654. doi: 10.1007/s40263-016-0359-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Australian Government Department of Health Therapeutic Goods Administration Scheduling basics. [Accessed May 14, 2018]. Available from: https://www.tga.gov.au/scheduling-basics.

- 44.Government of Canada Justice Laws website Controlled drugs and substances act. [Accessed May 14, 2018]. Available from: http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-38.8/

- 45.Peckham AM, Fairman KA, Sclar DA. Call for increased pharmacovigilance of gabapentin. BMJ. 2017;359:54–56. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peckham AM, Evoy KE, Covvey JR, Ochs L, Fairman KA, Sclar DA. Predictors of gabapentin overuse with or without concomitant opioids in a commercially insured U.S. population. Pharmacotherapy. 2018;38(4):436–443. doi: 10.1002/phar.2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. cca.hawaii.gov . Minutes of Meeting. Hawaii Board of Pharmacy; [Accessed December 7, 2017]. [updated August 17, 2017]. Available from: https://cca.hawaii.gov/pvl/files/2013/06/170817-min.doc.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 48. cca.hawaii.gov . Minutes of Meeting. Hawaii Board of Pharmacy; [Accessed December 7, 2017]. [updated September 21, 2017] Available from: https://cca.hawaii.gov/pvl/files/2013/06/170921-min.doc.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 49. ilga.gov . Illinois Compiled Statutes Section 316. Illinois General Assembly; [Accessed January 17, 2018]. Available from: http://www.ilga.gov/legislation/ilcs/fulltext.asp?DocName=072005700K316. [Google Scholar]

- 50. in.gov . Laws and Regulations. Indiana Professional Licensing Agency; 2018. [Accessed January 3, 2018]. Available from: https://www.in.gov/pla/inspect/2442.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 51. pharmacy.ks.gov . Proposed Regulatory Changes to KAR 68-21-7. Kansas Board of Pharmacy; [Accessed December 8, 2017]. {Updated September 7, 2017}. Available from: http://pharmacy.ks.gov/docs/default-source/statues-regulations/kar-68-21-7.pdf?sfvrsn=4da4a601_0. [Google Scholar]

- 52. pharmacy.ky.gov . Important Notice: Gabapentin Becomes a Schedule 5 Controlled Substance in Kentucky. Kentucky Board of Pharmacy; [Accessed December 8, 2017]. [Updated March 3, 2017]. Available from: https://pharmacy.ky.gov/Documents/Gabapentin%20-%20Schedule%20V%20Controlled%20Substance.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 53. mass.gov . Massachusetts PMP Data Submission Dispenser Guide. Massachusetts Prescription Monitoring Program; [Accessed December 13, 2017]. [updated August 30, 2017.] Available from: https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2017/09/12/pmp-data-submission-guide.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 54. pmp.pharmacy.state.mn.us . Minnesota PMP Data Uploaders. Minnesota Board of Pharmacy; [Accessed January 3, 2018]. [updated April 2017]. Available from: http://pmp.pharmacy.state.mn.us/pmp-data-uploaders.html. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Balick R. Nebraska pharmacists will report all prescriptions to state PDMP. Pharmacy Today. 2017 Nov;23(11):50–51. [Google Scholar]

- 56. njconsumeraffairs.gov . Rule Proposal. New Jersey Division of Consumer Affairs; [Accessed January 11, 2018]. [updated January 9, 2018]. Available from: https://www.njcon-sumeraffairs.gov/Proposals/Pages/directorsoffice-01022018-proposal.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 57. health.ny.gov . Internet System for Tracking Over-Prescribing – Prescription Monitoring Program. New York State Department of Health; [Accessed January 3, 2018]. [updated March 2017]. Available from: https://www.health.ny.gov/professionals/narcotic/prescription_monitoring/ [Google Scholar]

- 58. nodakpharmacy.com . Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Law. North Dakota Board of Pharmacy; [Accessed December 7, 2018]. Available from: https://www.noda-kpharmacy.com/pdfs/PDMPlaws.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 59. codes.ohio.gov . Dangerous drug monitoring. Ohio General Assembly; [Accessed December 8, 2017]. [updated December 1, 2016]. Available from: http://codes.ohio.gov/oac/4729-37-12. [Google Scholar]

- 60. capitol.tn.gov . House Bill 1832. General Assembly Of The State Of Tennessee; 2018. [Accessed January 24, 2018]. Available from: http://www.capitol.tn.gov/Bills/110/Bill/HB1832.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 61. lis.virginia.gov . HB 2164 Drugs of concern; drug of concern. Virginia General Assembly; [Accessed January 4, 2018]. [updated February 23, 2017]. Available from: https://lis.virginia.gov/cgi-bin/legp604.exe?171+sum+HB2164. [Google Scholar]

- 62. doh.wa.gov . Washington State Pharmacy Quality Assurance Commission Meeting Minutes. Washington State Department of Health; [Accessed January 24, 2018]. [updated December 15, 2017]. Available from: https://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/Mtgs/2017/20171215-MN-PH.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 63. doh.wa.gov . Washington State Pharmacy Quality Assurance Commission Meeting Minutes Draft. Washington State Department of Health; [Accessed January 24, 2018]. [updated October 27, 2017]. Available from: https://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/Mtgs/2017/20171215-AG-PH.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 64. qioprogram.org . West Virginia Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) Quality Improvement Organizations; [Accessed December 12, 2017]. [updated October 2017]. Available from: https://qioprogram.org/sites/default/files/editors/141/WV_PDMP_Recording_508.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 65. drive.google.com . Wyoming Prescription Drug Monitoring Program. Wyoming State Board of Pharmacy; [Accessed on December 13, 2017]. [updated October 27, 2017]. Available from: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B8cDfZ_Wrtc8bF-BUWGd5VDdJYU0/view. [Google Scholar]