Abstract

In the U.S. Black women with HIV face numerous psychosocial challenges, particularly trauma, racism, HIV-related discrimination, and gender role expectations, that are associated with negative HIV health outcomes and low medical treatment adherence. Yet many of these factors are unaddressed in traditional cognitive behavioral approaches. This study presents a case series of a tailored cognitive behavioral treatment approach for Black women living with HIV. Striving Towards EmPowerment and Medication Adherence (STEP-AD) is a 10-session treatment aimed at improving medication adherence for Black women with HIV by combining established cognitive behavioral strategies for trauma symptom reduction, strategies for coping with race- and HIV-related discrimination, gender empowerment, problem-solving techniques for medication adherence, and resilient coping. A case series study of five Black women with HIV was conducted to evaluate the preliminary acceptability and feasibility of the treatment and illustrate the approach. Findings support the potential promise of this treatment in helping to improve HIV medication adherence and decrease trauma symptoms. Areas for refinement in the treatment as well as structural barriers (e.g., housing) in the lives of the women that impacted their ability to fully benefit from the treatment are also noted.

Keywords: black women, HIV, trauma, medication adherence, cognitive behavioral therapy

Black women account for over 62% of women living with HIV in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016). In addition, Black women living with HIV (BWLWH) are less likely to be HIV virally suppressed (i.e., viral load at an undetectable level) and more likely to die from HIV-related illnesses (McFall et al., 2013) than White women, which in part is due to suboptimal HIV medication adherence. Optimal adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) is necessary to prevent the virus from replicating, transition from HIV to AIDS, and eventually death due to HIV-related complications (Lee et al., 2017). With adequate ART adherence, the HIV virus can become suppressed and there is a significant decrease in the risk of death from HIV-related complications (Hoffman & Gallant, 2014; Lee et al., 2017) as well as decreased risk of transmitting the virus to someone else. The optimal level of ART adherence is estimated to be at 80% or above (Bangsberg et al., 2000), but among racial/ethnic minority women estimated adherence is 45% to 64% (Howard et al., 2002).

A few psychosocial factors have been shown cross-sectionally to be particularly relevant for medication adherence among BWLWH, including histories of trauma/abuse, racial discrimination, HIV-related discrimination, and prescribed gender roles (e.g., ways women and girls are expected to behave, think, and feel; Brody, Stokes, Kelso, et al., 2014; Katz et al., 2013; Kelso et al., 2013; Leserman et al., 2007; Machtinger et al., 2012). For instance, over 67% of 2,000 HIV-positive and 500 HIV-negative participants in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) reported histories of physical, sexual, or emotional abuse (Cohen et al., 2000; Cohen et al., 2004) and abuse histories have been linked to medication nonadherence and increased mortality (Machtinger et al., 2012). Some women with histories of trauma/abuse may develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which is a combination of reexperiencing the trauma (e.g., nightmares, flashbacks), avoidance (e.g., pushing away thoughts, staying away from people who are reminders), negative changes in thoughts and mood (e.g., self-blame), and changes in reactivity (e.g., exaggerated startle response; APA, 2013). For women with HIV, receiving the HIV diagnosis is a traumatic stressor that may lead to PTSD symptoms (Nightingale, Sher, & Hansen, 2010).

Discrimination experiences based on race and HIV status are also ongoing stressors that Black women with HIV face. Authors of the Black Women’s Health Study found that 66% of Black women experienced discrimination on a monthly basis on the job, in housing, and/or by the police (Mouton et al., 2010) and HIV researchers have noted significant associations between racial discrimination and HIV medication nonadherence among African Americans (Bogart, Wagner, Galvan, & Klein, 2010). Similarly, BWLWH face HIV-related discrimination, which has also been associated with medication nonadherence among African Americans (Bogart et al., 2010). Black women are also socialized with traditional female gender roles (e.g., expectation to sacrifice self-needs in order to care for others; Bowleg, Belgrave, & Reisen, 2000), which are higher among women with HIV and have been linked with low ART adherence (Brody, Stokes, Kelso, et al., 2014; Brody, Stokes, Dale, et al., 2014). Given the relationships between trauma/abuse, racism, HIV-related discrimination, and gender roles with medication adherence among BWLWH, a treatment incorporating existing cognitive behavioral treatment strategies and addressing coping strategies for these issues might be beneficial in improving medication adherence.

Elements of established cognitive behavioral treatments for trauma/posttraumatic stress disorder (i.e., Cognitive Processing Therapy [CPT] and Prolonged Exposure Therapy) may be beneficial in a treatment for women with HIV and histories of abuse (Foa, Rothbaum, Riggs, & Murdock, 1991; Resick, Nishith, Weaver, Astin, & Feuer, 2002). Elements include delivering information about PTSD, writing an impact statement about the traumatic event, and exploring and correcting negative thoughts (e.g., low self-worth) relating to the traumatic event that may interfere with self-care behaviors (e.g., medication adherence; Foa et al., 1991; Resick et al., 2002). A limited number of treatment studies specifically address trauma among individuals with HIV, and these have shown significant decreases in trauma symptoms and sexual risk behaviors (Sikkema et al., 2008; Sikkema et al., 2007; Wyatt et al., 2004). Of these three studies, one examined medication adherence and did not show an effect, while two studies did not examine medication adherence (Sikkema et al., 2008; Sikkema et al., 2007; Wyatt et al., 2004). In addition, existing trauma-focused treatments for women with HIV do not include, as part of the treatment, potentially important components such as discrimination experiences for BWLWH.

A few interventions incorporating gender empowerment among women with and at risk for HIV have shown efficacy in reducing sexual risk behaviors (DiClemente & Wingood, 1995; Wingood et al., 2004). For instance, DiClemente and Wingood's (1995) intervention Sisters Informing Sisters About Topics on AIDS (SISTA), which includes content on gender pride and assertiveness skills, showed efficacy in decreasing sexual risk behaviors for heterosexual African American women. Similarly, the Women Involved in Life Learning From Other Women (WiLLOW) intervention for women living with HIV encourages gender pride and has demonstrated efficacy in decreasing sexual risk behaviors among diverse groups of women (Wingood et al., 2004). However, there is currently no existing efficacious intervention for women with HIV that incorporates gender roles and empowerment (e.g., assertive communication with providers), as part of ways to increase medication treatment adherence.

Behavioral treatments that directly aim to increase ART adherence also need additional refinement. To date, the majority of interventions to increase ART adherence among HIV-infected participants have yielded modest effects (Amico, Harman, & Johnson, 2006; Simoni, Pearson, Pantalone, Marks, & Crepaz, 2006). One approach to enhance the efficacy of these interventions is to address co-occurring psychosocial problems (such as depression), given their relationship with nonadherence. In individuals with HIV and depression, for example, Life-Steps, a single-session cognitive-behavioral problem-solving intervention for medication adherence (Safren, Otto, & Worth, 1999; Safren et al., 2001), has shown efficacy when combined with CBT strategies addressing depression (Safren et al., 2009; Safren et al., 2012 ). More specifically, Life-Steps includes psychoeducation on the benefits of being adherent with ART, review and brief modification of participants’ nonadaptive cognitions about taking their medications, review of commons barriers to adherence, and teaching of problem-solving techniques for problematic areas with adherence (Safren et al., 1999; Safren et al., 2001). Combining the single session of Life-Steps with tools addressing psychosocial issues for BWLWH might be beneficial.

While there are no interventions that have shown to increase adaptive coping with racism and HIV-related discrimination, there are existing coping strategies that have been noted in the literature among BWLWH and Black individuals in general (Bogart et al., 2016; Dale et al., 2017; Forsyth & Carter, 2012). Coping strategies for racial discrimination highlighted in these studies include social support, assertiveness, caution, ignoring the perpetrator, taking legal action, spirituality, racial consciousness (i.e., connecting with one's cultural heritage to take action against racism), and bargaining (e.g., changing one's behavior to manage others' perceptions). Forsyth and Carter (2012) suggested having clients examine the pros and cons of these coping strategies (e.g. bargaining) and enhance racial consciousness. Existing literature suggests that Black women living with HIV may cope with discrimination via selective/nondisclosure of their HIV status, education/knowledge, and avoidance, internalized stigma (e.g., self-hate), seeking support, and praying (Dale et al., 2017; Varni, Miller, McCuin, & Solomon, 2012).

Other resilient coping strategies may also promote medication adherence, but efficacy/effectiveness also remains unexplored. Resilience can include personal characteristics such as commitment, sense of humor, optimism, self-efficacy, self-esteem, having a realistic sense of control, being action and goal-oriented, viewing stress as a challenge/opportunity, and being able to adapt to change (Connor & Davidson, 2003). Three studies on resilience among women with HIV were conducted and greater than 80% of the sample was Black. Findings showed that (a) higher resilience (characteristics noted above) was associated with undetectable viral load and higher medication adherence, (b) resilience buffered the relationships between abuse histories and ART adherence, and (c) higher resilience was associated with lower traditional gender role beliefs (Dale, Cohen, Kelso, et al., 2014; Dale, Cohen, Weber, et al., 2014; Dale et al., 2015).

Description of Treatment Approach

Overview of Approach

Interviews with BWLWH were previously conducted, qualitatively analyzed, and published (Dale et al., 2017), and those findings were used to inform the development of the Striving Toward EmPowerment and Medication Adherence (STEP-AD) intervention. As depicted in Table 1, the STEP-AD treatment consists of 10 sessions delivered on a weekly basis with content on (a) Life-Steps for Medication Adherence, (b) Psychoeducation on the CBT treatment model, (c) PTSD and Cognitive Strategies, (d) Strategies for Racial Discrimination and HIV Discrimination, (e) Gender-Related Coping and Resilience, and (f) Practice, Review, and Relapse Prevention. These are detailed below.

Table 1.

Striving Towards Empowerment and Medication Adherence (STEP-AD) Manual Components

| Sessions | Focus |

|---|---|

| 1. Life-Steps for Medication Adherence (session 1) | 1. Use a tailored version of Safren’s Life-Steps (Safren et al., 2001) intervention with cognitive-behavioral, problem-solving, and motivational interviewing techniques to promote adherence. |

| 2. Psychoeducation on the Treatment Model (session 2) | 1. Present connections between symptoms of trauma/abuse, racial discrimination, and gender related coping with medication nonadherence and how adaptive strategies for addressing trauma, coping with racial discrimination, and enhancing gender empowerment and resilience may moderate effects. |

| 3. PTSD and Cognitive Strategies (sessions 3 & 4) | 1. Provide in-depth psychoeducation on trauma,

PTSD, and how trauma symptoms/cognitions (e.g. negative self-worth) are

linked to medication nonadherence. 2. Teach strategies to correct negative thoughts from trauma linked to nonadherence. |

| 4. Strategies for Racial Discrimination and HIV Discrimination (sessions 5 & 6) | 1. Review the link between racial and HIV discrimination with medication adherence, discuss different strategies for coping with racism and HIV discrimination, explore coping strategies the participant tends to utilize, assist the participant in weighing the benefits and/or costs of using these various coping strategies, minimize use of nonadaptive strategies, and enhance use of adaptive strategies. |

| 5. Gender-Related Coping and Resilience (sessions 7 & 8) | 1. Review gender-related coping strategies

that women tend to utilize, minimizing use of strategies that relate to

medication nonadherence and enhancing use of adaptive strategies (e.g.

self-advocacy). 2. Define the resilience concept and its association with medication adherence, discuss coping strategies and techniques (e.g. viewing obstacles as challenges) utilized by resilient individuals following trauma, and assist the participant in eliciting evidence of her resilience and coping strategies to optimize her resilience in terms of adherence. |

| 6. Practice, Review, and Relapse Prevention (sessions 9 & 10) | 1. Continue to reinforce the correction of

negative trauma thoughts and coping strategies for racial and HIV

discrimination, gender empowerment, and resilience that are related to

medication adherence. 2. Discuss relapse prevention and continue to reinforce coping and adherence skills. |

Life-Steps for Medication Adherence (Session 1)

Lifesteps (Safren et al., 2001) is a one-session intervention with cognitive-behavioral, problem-solving, and motivational interviewing techniques to promote adherence. The Life-Steps session includes psychoeducation on the benefits of being adherent with ART, modification of participants’ nonadaptive cognitions about taking their medications, review of common barriers to adherence, and teaching of problem-solving techniques for problematic areas with adherence.

Psychoeducation on the Treatment Model (Session 2)

Starting with Session 2, at the beginning of each session participants’ medication adherence and trauma symptoms are reviewed. The purpose of Session 2 is to lay the groundwork for future sessions, with particular focus on the impact of their trauma and the various stressors typically faced by Black women living with HIV. Accordingly, there are three main components to this session that involve interactively discussing (a) connections between trauma/abuse, race- and HIV-related discrimination, and gender-related coping with self-care (e.g., medication adherence, engagement in enjoyable activities), (b) how adaptive strategies for addressing trauma, coping with race- and HIV-related discrimination, and enhancing gender empowerment and resilience may mitigate the negative effects of these stressors, and (c) the symptoms of trauma and PTSD. A visual model is presented to the participants to communicate that adversities may have or continue to invalidate their sense of self/worth and may be linked to neglecting their self-care (e.g., medication adherence). Session 2 also consists of having participants set personal goals for the treatment (e.g., adherence, overall engagement in care, decrease maladaptive coping), discussing the importance of self-care (e.g., medication adherence and engagement in enjoyable activities), and having the participant select and/or generate a list of self-care activities (e.g., bubble bath, walking). In preparation for between-session homework, participants have an opportunity to briefly discuss a primary traumatic memory to work on during this treatment. For between-sessions homework, participants are then asked to (a) plan two (or more) daily self-care activities (at least one around health engagement/adherence) and monitor their mood before and after each activity and (b) write their impact statement about how the traumatic event influenced who they are today, how they feel, and how they think about themselves, their future, and others. Instead of the term “impact statement,” used in existing evidence-based trauma treatments such as CPT (Resick et al., 2002), throughout this treatment women’s essays are referred to as “survival stories” and go beyond the impact of trauma, per se, to include how they were/are impacted by racism, HIV discrimination/stigma, and gender roles. After initially writing their survival stories about a key traumatic event, women are asked to rewrite their survival stories in between sessions (similar to rewriting the impact statement in CPT) and each time include how an additional adversity has impacted them (e.g., adding racism between Sessions 4 and 5). Women are also given the option to audio record their stories and/or tell them to the clinician. In addition, the clinician emphasizes to each woman that while writing her story she should not be concerned with grammar and spelling, because however she writes her story is how it needs to be told.

Addressing Trauma Symptoms via Cognitive Strategies (Sessions 3 and 4)

Sessions 3 and 4 consist of (a) having participants read their survival stories, (b) helping them to pull out the negative cognitions within their survival stories, (c) presenting/discussing common negative cognitions (e.g., negative self-worth) held by trauma survivors and how they may be linked to medication nonadherence, and (d) teaching participants a cognitive restructuring technique to correct negative thoughts from trauma, especially those linked to nonadherence. We use a metaphor of a prosecutor versus a defense lawyer and frame negative cognitions as things that a prosecutor might say to keep someone caged by their past trauma and frame adaptive thoughts as things that a defense lawyer would say to help someone move and live free, despite their past. Our approach is similar to an aspect of trial-based cognitive therapy that uses courtroom nomenclature to label and teach cognitive therapy strategies (De Oliveira et al., 2012). Women are encouraged to practice being their own best “defense attorney” against the negative cognitions trauma left behind.

Following Session 3, between-sessions practice involves working with participants to try to (a) plan two (or more) self-care activities (at least one on health engagement/adherence) and monitor their mood before and after each activity, (b) track negative and positive cognitions they have, and (c) rewrite their survival story about how the traumatic event influenced who they are today, how they feel, and how they think about themselves, their future, and others. After Session 4 between-session work involves helping participants (a) plan two (or more) self-care activities (at least one around health engagement/adherence) and monitor their mood before and after each activity, (b) track and practice being their own “defense attorney” against negative cognitions, and (c) rewrite their "survival story" about their trauma and now add how their experiences with racism (in preparation for the next session) has influenced who they are today, how they feel, and how they think about themselves, their future, and others.

Coping Strategies for Racial Discrimination and HIV Discrimination (Sessions 5 and 6)

Sessions 5 and 6 are dedicated to (a) reviewing the link between race- and HIV-related discrimination with medication adherence, (b) discussing different strategies for coping with racism and HIV-related discrimination, (c) exploring coping strategies the participant tends to utilize, (d) assisting the participant in weighing the benefits and/or costs of using these various coping strategies, minimize use of nonadaptive strategies (e.g., self-hate, changing one's behavior to manage others' perceptions), and enhance use of adaptive strategies (e.g., racial consciousness, advocacy, seeking support, selective disclosure of HIV status).

After Session 5, between-session work involves helping participants to (a) plan two (or more) self-care activities (at least one around health engagement/adherence) and monitor their mood before and after each activity, (b) track and practice being their own defense attorney against negative cognitions, (c) track and note what coping strategies they utilized around any experiences with racial discrimination, (d) rewrite their "survival story" about their trauma and racism and now add how their experiences with HIV-related discrimination/stigma (in preparation for the next session) has influenced who they are today, how they feel, and how they think about themselves, their future, and others. Following Session 6, the between-sessions homework is the same with the exceptions of (a) also tracking and noting what coping strategies they utilize around any experiences with HIV-related discrimination and (b) including in their survival story how their experiences with gender-related stressors (in preparation for the next session) has influenced who they are today, how they feel, and how they think about themselves, their future, and others.

Gender-Related Coping and Resilience (Sessions 7 and 8)

The purpose of Sessions 7 and 8 is to (a) review gender-related coping strategies that women tend to utilize, minimizing use of strategies that relate to medication nonadherence (e.g., sacrificing their own needs to care for others, self-silencing their thoughts and feelings to maintain harmony with others) and enhancing use of adaptive strategies (e.g., self-advocacy, prioritizing their own needs) and (b) define the resilience concept and its association with medication adherence, discuss coping strategies and techniques (e.g., viewing obstacles as challenges) utilized by resilient individuals following trauma, and assist the participants in eliciting evidence of their resilience and coping strategies to optimize their resilience in terms of adherence. Following Session 7, the work outside of sessions maintains the same structure as prior sessions, with the exceptions of (a) also tracking and noting what coping strategies they utilized around any experiences with gender-related stressors, and (b) including in their survival story how they have been resilient and have coped adaptively in the face of adversities.

Practice, Review, and Relapse Prevention (Sessions 9 and 10)

Sessions 9 and 10 provide an opportunity to (a) continue to work on the correction of negative trauma thoughts and the use of adaptive coping strategies for race- and HIV-related discrimination, gender empowerment, and resilience that are related to medication adherence and (b) discuss relapse prevention.

To further elaborate on the STEP-AD treatment approach below, we discuss the study procedures and measures, followed by five case descriptions of BWLWH who were enrolled in the open pilot phase.

Participants and Procedures

Participants were recruited in an urban city in the Northeastern United States by distributing flyers in community-based clinics and organizations as well as presenting information about the study at community events and to providers who service BWLWH. After hearing about the study or seeing a posted flyer potential participants contacted the study research coordinator via phone. The research coordinator conducted a phone screen and if the potential participant met the screening criteria, they were scheduled for a baseline visit. The baseline visit was conducted across two visits with a 2-week interval. At the initial baseline visit, participants were engaged in the informed consent process, and completed self-report and clinician-administered measures (e.g., Davidson Trauma Scale), described below in the measures section. Participants then received a Wisepill adherence monitor (see Haberer et al., 2010) to use over the two weeks. The Wisepill device is a pillbox that tracks when it is opened and closed in real-time and sends a signal to a central server for monitoring.

At the second baseline visit participants were provided feedback on their assessment and informed that they qualified for the treatment if they met all of the following inclusion criteria: (a) HIV-positive, (b) identify as Black or African American, (c) age 18 or older, (d) natal female, (e) basic proficiency in English, (f) currently taking ART medication and low ART adherence (<80 %) or detectable viral load within the past 6 months, and (g) history of abuse/trauma. Exclusion criteria included: (a) inability (e.g., due to cognitive or psychiatric difficulties) or unwillingness to provide informed consent, (b) significant mental health diagnosis requiring treatment (e.g., unstable bipolar disorder; any psychotic disorder), or (c) recent (past 6 months) behavioral treatment for ART adherence or trauma. Fifteen participants assessed at baseline were not included in the treatment because they did not meet all inclusion criteria (e.g., were adherent to their medication above the 80% cutoff and had an undetectable viral load for the past 6 months) or met an exclusion criteria (e.g., significant unaddressed mental health diagnosis). All five participants included in the treatment were asked to continue to use the Wisepill adherence throughout the treatment and follow-up period. The 10-session treatment was delivered by a race and gender-matched (Black female) psychologist on a weekly basis within approximately 3 months. The Black female psychologist grew up and lived in a majority Black and low-income community similar to (and often the same) as study participants. However, recognizing that the composition of the Black community is diverse and multifaceted, the psychologist was mindful of assumed norms, lifestyles, and values and sought to see each woman and her specific story. All assessment measures given at baseline were readministered at 3 and 6 months from the initial baseline by postbaccalaureate and doctoral-level Black women who served as independent assessors. Participants received $50 for each major assessment (baseline, 3-month FU, 6-month FU) and $25 for each weekly visit. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Partners HealthCare.

Measures

ART Adherence

HIV medication adherence was captured via the Wisepill medication monitor (Haberer et al., 2010). With Wisepill a single medication (which the participant took the most frequently, or which they had the most difficulty in taking) was monitored. Percent ART adherence (days Wisepill was opened ÷ total days) was calculated for the 2 weeks preceding the second baseline visit and the follow-up visits (3 and 6 months).

Viral Load

Medical records were reviewed for available information on participants' HIV viral load within the 6 months preceding baseline, after treatment completion, and during/after follow-up. Undetectable viral load was less than 20 copies/mL, with values at or above 20 copies/mL indicating a detectable viral load and higher amounts of HIV in the blood.

The Davidson Trauma Scale (Davidson et al., 1997)

The DTS is a measure (17 items) of PTSD symptoms with good internal consistency (r = .99). Each item assesses both the frequency (4 = “every day”) and severity (0 = “not at all distressing”) of a symptom within the past week. The total score ranges from 0 to 136. In the general population average DTS scores were found to be 64.4 ± 29.7 for a subgroup with threshold PTSD, 31.9 ± 28.2 for a subgroup with subthreshold PTSD and impairment, and 19.6 ± 16.7 for a subgroup with nonimpaired subthreshold PTSD (Davidson, Tharwani, & Connor, 2002).

Case Examples

For each of the five case examples, we describe background information, adherence level and trauma symptoms at baseline, course of STEP-AD, and outcome data. In order to protect participant confidentiality, we changed some details about each participant.

Case Study 1

Background

Maya was a 42-year-old Black woman who was originally born in the Caribbean and for whom English was a second language. At baseline Maya’s ART adherence was 71% and her HIV viral load was detectable within the past 6 months. She was prescribed 1 ART pill to take once per day. Maya reported several past traumatic events, including childhood sexual abuse by her stepfather, physical and verbal abuse by her ex-partner from whom she contracted HIV, and first learning of her HIV-positive status in the ER as her partner was passing away from AIDS. Of these traumatic events Maya stated that her memories and thoughts of her childhood sexual abuse bothered her the most and she scored 73 on the DTS, which is above threshold PTSD symptoms. Maya had previously been employed as a medical assistant; however, she was in the process of applying for SSDI. Maya resided in her own apartment with her two sons (an adolescent and an adult), with whom she has close relationships. She also stayed in contact with her mother and siblings, who resided locally, as well as extended family members who lived in the Caribbean. Maya reported that she spent most of her days indoors at home.

Course of STEP-AD

In the Life-Steps adherence counseling session, Maya was able to discuss the important reasons why she wanted to be optimally adherent to her HIV medication (e.g., to be healthy and alive for her kids) and problem-solve ways to improve communication with her care team. However, one major barrier to her adherence was that when she looked at her medicines, she would typically think negative thoughts (e.g., “I hate myself”; “I should have known better”; “Is the medication really working?”). This became the basis for some of the cognitive restructuring in later sessions. Additionally, a second barrier that emerged for her was effectively communicating with her treatment team. Maya felt uncomfortable expressing issues (e.g., medication side-effects) to her providers. Per the Life-Steps intervention, Maya and the clinician utilized index cards for her to bring to her next appointment, and wrote down questions she wanted to ask. In addition, Maya’s discomfort with speaking with providers was addressed in the session on gender roles (described later).

Session 2 presented the treatment model, which conveys that adversities such as trauma, racism, HIV-related discrimination, and gender roles can negatively impact a Black woman’s self-worth and self-esteem and lead to neglecting self-care (e.g., not taking medications) and unhealthy coping. As this was done interactively, Maya stated that she felt that the treatment model resonated with her negative experiences and how they made her feel and behave. She expressed that she was eager to learn tools to address her trauma, feel more empowered in who she was, and take better care of her health. Her primary goal for the course of the treatment was to take her medication everyday and to stop the negative thoughts (about HIV and past trauma) that she has when she is about to take her ART medication that sometimes prevents her from taking them. She also expressed that many of the symptoms of trauma were things that she continues to struggle with (e.g., intrusive memories, flashbacks, negative beliefs/feelings). Maya selected/generated a list of self-care activities (e.g., exercise, cook, watch comedy clips) she could engage in as part of her self-care homework between sessions. While Maya was initially hesitant about writing her survival story between sessions due to anticipated distress, she stated that she understood the rationale for writing it and felt comforted by the planning done with the clinician (e.g., take multiple breaks as needed, engage in a self-care activity immediately after).

Maya was very engaged over the course of the three sessions that focused on processing the trauma she wrote about in her survival story, eliciting her trauma-related cognitions, and learning/practicing cognitive restructuring skills. Maya wrote about the impact of the childhood sexual abuse on how she thought about herself in a negative light and was very insightful in connecting her childhood sexual abuse history and parental neglect with her risk for entering in an abusive relationship with her ex-partner from whom she contracted HIV. Maya quickly grasped the metaphor of being her own best defense attorney against the negative trauma-related cognitions that arise throughout her day and especially in the context of taking her HIV medications.

For the sessions on racial discrimination and HIV-related discrimination, Maya shared adaptive (e.g., blaming the appropriate person and focusing on her internal power) and unhelpful coping strategies she had been using (e.g., avoiding HIV facilities/organizations). She was able to weigh the pros and cons of various strategies and the importance of going to facilities that increase her access to health resources.

The session on gender roles resonated well with Maya because she reported self-silencing (not speaking up) with providers about medication side effects and her preferences. She also prioritized the desires of others above her own. For instance, she reported going without basic needs (e.g., shoes) in order to purchase brand-named sneakers for her son and finding it difficult to say no to family members in the Caribbean who called and asked for money on a monthly basis. Via this session and highlighting the potential benefits of self-advocacy and self-primary, Maya spoke with a treatment provider and had a medication adjusted (led to a decrease in her side-effects) and began to try to set limits with family members around how much money she could give.

Across sessions on resilience and relapse prevention, Maya enthusiastically shared the ways she had been resilient in the past and how the skills she was practicing (e.g., cognitive restructuring) throughout the treatment had increased her resilience to help her to (a) move beyond her past trauma, (b) better adhere to her medication, and (c) cope with discrimination and gender roles.

Outcome Data

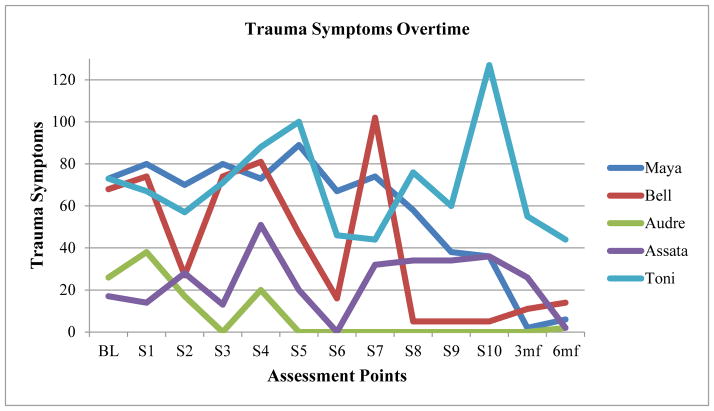

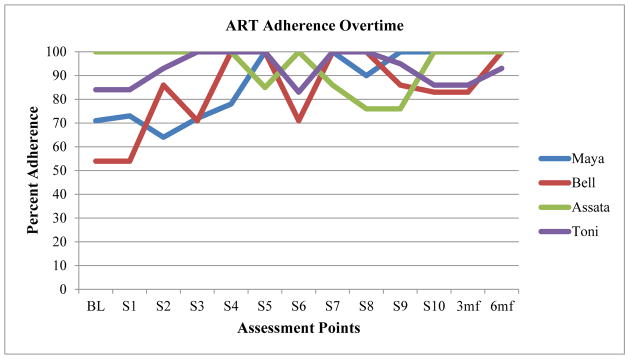

Throughout the treatment Maya attended all sessions as scheduled and completed all homework assignments (e.g., survival story, enjoyable activities). As depicted in Figures 1 and 2 and Table 2, in comparison to her baseline scores by her 3-month and 6-month follow-ups, Maya had an increase in her HIV medication adherence and decrease in her PTSD symptoms on the Davidson Trauma Scale. Maya’s medical records did not include information on HIV viral load near the 3-month follow-up and near the 6-month follow-up her viral load was detectable at a level close to her baseline viral load.

Figure 1.

Trauma Symptoms Overtime for Open Pilot Case Series

Figure 2.

ART Adherence Overtime for Open Pilot Case Series

Table 2.

Baseline and Follow-up Assessment Results for Open Pilot Case Series

| % ART Adherence | Viral load /status | Trauma symptoms | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case Study 1: Maya | |||

| Baseline | 71 | 1100 (detectable) | 73 |

| 3 month | 100 | Not available | 2 |

| 6 month | 100 | 1000 (detectable) | 6 |

| Case Study 2: Bell | |||

| Baseline | 54 | 20 (detectable) | 68 |

| 3 month | 83 | Not available | 11 |

| 6 month | 100 | 44 (detectable) | 14 |

| Case Study 3: Audre | |||

| Baseline | Did not start ART | 295 (detectable) | 26 |

| 3 month | Did not start ART | 473 (detectable) | 0 |

| 6 month | Started ART | 0 undetectable | 2 |

| Case Study 4: Assata | |||

| Baseline | 100 | 524 (detectable) | 17 |

| 3 month | 100 | Not available | 26 |

| 6 month | 100 | Not available | 2 |

| Case Study 5: Toni | |||

| Baseline | 84 | 32 (detectable) | 73 |

| 3 month | 86 | Not available | 55 |

| 6 month | 93 | 66 (detectable) | 44 |

Case Study 2

Background

Bell was a 37-year-old African-American female who migrated from another state within the past decade. She was previously employed as a nurse and currently received SSDI as her primary source of income. Bell resided in her own apartment and maintained contact with her family (mother, siblings, and children/grandchildren), who lived in her state of origin. At baseline Bell’s ART adherence was 50% and her HIV viral load was detectable within the past 6 months. She was prescribed 1 ART pill to take once per day. Bell reported several traumatic events that had occurred in the past, including physical and emotional abuse by an ex-partner who choked her until she lost consciousness and losing her father to cancer with minimal notice. The choking/near-death experience was the trauma that continued to bother her the most and she scored 68 on the DTS, which is above threshold PTSD symptoms.

Course of STEP-AD

The LifeSteps session elucidated barriers to Bell’s medication adherence, such as thoughts of hoping that one day she will never have to take them again (“her body will heal itself”), stressors, low mood, and forgetfulness. Bell generated reasons (e.g., grandchildren) for taking her medication and generated strategies to help her to remember, such as taking her medication at mealtime and posting brightly colored stickers provided by the clinician throughout her apartment.

Bell was engaged in Session 2 as she and her clinician discussed the treatment model and learned via psychoeducation about the impact of trauma. Many of her PTSD symptoms were symptoms she had struggled with in the past and continued to struggle with (e.g., avoiding thinking about the trauma, avoiding reminders, unable to feel sad or loving feelings). Her primary goal for the course of the treatment was to deal with situations more effectively and not become irritated or angry quickly (e.g., “not be easily upset by disappointments”), improve her ART adherence to prevent developing any medication-resistance, and engage in more self-care activities. Bell selected/generated self-care activities to do for between-sessions homework (e.g., bubble baths, praying, and going for walks). Similar to other participants Bell was hesitant to write her survival story, but discussing with the clinician when she could write (night or morning before session) and how she could cope with emotions that came up was beneficial.

Bell’s PTSD symptoms were activated over the course of Sessions 3 and 4 and focused on processing the trauma she wrote about in her survival story, eliciting her trauma-related cognitions (especially in the context of ART adherence), and learning/practicing cognitive restructuring skills. However, she remained engaged, utilized skills that she learned, and experienced a sharp drop in PTSD symptoms following Session 5. There was a spike in Bell’s PTSD symptoms again at Session 7 when her adult daughter was hospitalized due to suicidal ideations, but Bell’s PTSD symptoms immediately decreased thereafter and remained lower throughout the remainder of the treatment and across follow-up visits.

Bell was actively engaged in Sessions 5 and 6 on racial discrimination and HIV-related discrimination and she was able to note the coping strategies she had previously used (e.g., advocacy, spirituality, selective disclosure) and weigh the pros and cons of the coping strategies discussed. For instance, she spoke about being aware that racism is ongoing and needing to be flexible in her coping responses (e.g., stopping legal action against the police) in order to prioritize her personal safety and prevent potential retaliation.

Session 7 on gender roles was timely as the participant saw the echoes of gender roles in the pressure from family members to move back to her state of origin. Bell was able to discuss alternative ways of coping (e.g., prioritizing self-care) and how remaining in this state provided housing stability, access to resources, and consistent medical care, which in turn increased her ability to visit her family and provide help as needed. Bell also began to set firmer boundaries and limited the frequency of phone contact with some family members whose conversation often elevated her distress.

Throughout the remaining sessions (8 and 9) Bell was able to reflect on evidence of her resilience, skills learned in the treatment, as well as draft a relapse prevention plan. Bell was excited about the decrease in her PTSD symptoms and the improvement in her medication adherence. However, she was also concerned about being able to maintain her gains without ongoing weekly sessions with the clinician.

Outcome Data

Throughout the treatment Bell attended all sessions as scheduled and completed the majority of homework assignments (e.g., enjoyable activities, survival story), except for the week her daughter was hospitalized. From baseline to follow-up visits (see Figures 1 and 2 and Table 2) there was an increase in Bell’s HIV medication adherence and decrease in her PTSD symptoms. Bell’s medical records did not include information on HIV viral load close to the 3-month follow-up and close to the 6-month follow-up her viral load was detectable at a level near her baseline viral load value.

Case Study 3

Background

Audre was a 53-year-old African American woman who was residing with her lifelong male partner, who was also living with HIV. Audre volunteered part-time at a nonprofit organization and received SSDI benefits. In early childhood an adult family member threw a brick at Audre’s head and that resulted in her being in a coma for several months in childhood. However, Audre read well and demonstrated sufficient cognitive skills to benefit from the treatment. In addition to this trauma, Audre had experienced intimate partner violence, physical abuse as a child, and exposure to domestic violence as a child. Audre reported that the past intimate partner violence (5 year span) was the trauma that continued to bother her the most and she scored 26 on the DTS, which falls midway between nonimpaired subthreshold PTSD and subthreshold PTSD with impairment. At baseline Audre was not taking HIV medication and had a detectable viral load. According to Audre and her providers, Audre’s viral load had been detectable yet stable for over 10 years/since she was diagnosed and Audre was opting not to take ART (despite her doctor’s recommendation). An exception was made to enroll Audre in the treatment despite her not being on ART, to address her PTSD symptoms and increase her openness to taking ART.

Course of STEP-AD

The Life-Steps session was used to discuss potential barriers Audre anticipated if she began taking ART (e.g., forgetting to take medication, side-effects) and to generate potential solutions (e.g., phone alarm, taking ART at a routine time, asking providers about different ART regimens and ways to minimize side-effects). Audre articulated the reason why she is choosing not to take ART (e.g., HIV viral load remains low and stable) and a reason why she would begin taking ART (if her viral load started to increase and her health was compromised).

In Session 2 Audre and the clinician discussed the treatment model and Audre shared that the content around using unhealthy methods (especially substance use) to cope with adversity resonated with her. This is because Audre reported using heroin and alcohol for years in the past (abstinent from both for 9 years). As part of the discussion, Audre generated several specific self-care activities that she would like to engage in (e.g., Zumba, dance, listen to music, read, exercise). Audre’s personal goals for the program were to continue to attend her medical appointments, continue her sobriety from alcohol and crack cocaine, and eat healthy.

When it was time to write the survival story, Audre chose to write about a trauma she witnessed as a child (i.e., domestic violence, mother assaulting a friend with a knife), her mother’s addiction, the constant presence of “strange men” in her home, and abuse that her mother perpetrated on her. Audre shared the insight that she felt that the cause of her mother being abusive and neglectful to her may have been due to “the cycle of abuse” in that her mother was also abused as a child. In general, Audre was engaged throughout Sessions 3 to 4 around the processing of her traumatic memories, discussing trauma-related cognitions, and learning/practicing cognitive restructuring skills. Her PTSD symptoms consistently remained at 0 from Session 5 and onward.

During Session 5 Audre shared stories of racial discrimination and trauma she experienced as a younger child (e.g., having White students threaten to assault her and other Black students with bats and sticks), ways she coped then (e.g., seeking support from classmates/teachers), and how now having a greater awareness of racism helps her to cope with even the more subtle forms of racism and micro-aggressions. Audre was also able to weigh the pros and cons of different coping responses to racism. Similar to Session 5, in Session 6, Audre shared her memory of first contracting HIV and her experiences of HIV discrimination/stigma (e.g., as an adult being kicked out of family housing because of her HIV status) and ways she copes today (e.g., viewing her HIV status in a positive way [Heaven in View], seeking support, and selectively disclosing her HIV status).

Session 7 focused on gender roles and adaptive ways to cope with gender role expectations. Audre was able to highlight ways in which family members and others expect her to prioritize their needs (e.g., babysitting, giving money), the negative impact of putting others first (e.g., exhaustion, not having money to take care of her needs), and ways she is learning to set boundaries and put herself first (e.g., going home to rest after volunteering and saying no to babysitting). Audre also discussed the positives of sharing household tasks, resources, and decision-making power with her partner.

In Session 8, Audre reported that she was excited to share her revised survival story that incorporated evidence of her resilience over the years and how she plans on staying resilient moving forward (e.g., loving herself, remaining sober, continuing to volunteer). Several of the resilient coping strategies discussed in session (e.g., humor, believing in her ability to adapt) resonated with Audre and she had seen the benefit of using them previously.

Across Sessions 9 and 10 Audre remained engaged as the treatment content and skills were reviewed, continued to practice skills (e.g., cognitive restructuring) and engage in enjoyable activities, and developed a plan for relapse prevention. Audre remained committed to attending her doctors’ visits to check her HIV viral load regularly and expressed that she would start ART if her viral load increased at her next bi-annual visit.

Outcome Data

Audre attended all the sessions and was actively engaged in discussions about the session content. She also completed all homework assignments (e.g., enjoyable activities, survival story) and often wrote long and insightful survival stories. By her 3- and 6- month follow-up visits there was a significant decrease in Audre’s PTSD symptoms (see Figure 1 and Table 2) and close to her 6-month visit she began taking ART as indicated in her medical records. According to her medical records, near her 3-month follow-up Audre had a detectable viral load—however, near her 6-month follow-up her viral load was undetectable.

Case Study 4

Background

Assata was a 49-year-old African-American woman who worked part-time as a home health aide, attended college part-time in pursuit of a certificate in counseling, and received SSDI benefits. She was also in a current relationship with evidence of verbal abuse although she expressed no concerns about her physical well-being. In addition, Assata had a history of abusing cocaine and heroin, but she was sober for 7 months at the start of this study. At baseline Assata’s ART adherence was 100%, but she had a detectable viral load within the past 6 months. She was prescribed 2 ART pills to take once per day. Assata also reported a pattern of going off of her medication (“medication vacation”) when she experienced stressors. She reported a history of multiple traumas, including childhood sexual and physical abuse by an older brother, a near lethal stabbing by the same brother as an adult, witnessing domestic violence in her family, and seeing the shooting death of an adolescent in her community. Assata noted that the childhood sexual abuse was the traumatic event that stuck with her the most and she scored 17 on the DTS, which falls 2 points below the average for nonimpaired subthreshold PTSD.

Course of STEP-AD

In the Life-Steps sessions Assata was able to generate reasons why she wanted to adhere to her HIV medication (e.g., staying alive and avoiding complications) and shared negative cognitions about her medications (e.g., “I caused it on myself”; “HIV medication is toxic”), but noted no logistical barriers to taking her medication (e.g., obtaining, storing) nor issues communicating with her providers. Assata was receptive to utilizing reminders (e.g., placing stickers around the house) and a schedule for when she takes her medication.

In Session 2 Assata expressed distress about issues in her intimate relationship and was momentarily tearful; nonetheless, she was engaged in Session 2. She was able to draw connections between (a) the treatment model and her current relationship stressors and (b) psychoeducation on the impact of trauma and how her own trauma history may be connected to her ongoing feelings of low self-worth. Her primary goals for the course of the treatment were to take care of her physical health (take medication and "no medication vacations"; lose weight) and have a healthier intimate relationship. Assata selected/generated self-care activities to do for between-sessions homework (e.g., watch movies, join support groups for women, exercise). Also, Assata planned to write her survival story the morning before the next session in order to be able to process any emotional distress the same day.

The purpose of Sessions 3 to 5 was to process the trauma Assata wrote about in her survival story, elicit her trauma-related cognitions (especially in context of ART adherence), and assist her in learning/practicing cognitive restructuring skills. However, Assata avoided writing about her trauma because she wanted to remain in the “here and now” and feared that looking back at her past trauma would make her sad and trigger a substance use relapse. Instead, Assata chose to write about her journey to recovery from substance, her recent decision to break up with her partner, and adaptive coping strategies she was using (e.g., seeking support, going to school). Assata was also open to discussing some ways that past trauma impacted her as an adult (substance use, abuse in relationships, view of the world as a dangerous place). At Session 3, Assata also shared that there was a recent shooting at her apartment building, which increased her PTSD symptoms (e.g., fear, hypervigilance, hyperarousal, and sleep disturbance). As a result, these sessions focused on enhancing Assata’s day-to-day coping (e.g., self-care activities) and having her practice restructuring unhelpful negative cognitions, and less emphasis was placed on revisiting her past trauma.

Assata reported an elevated level of distress in Session 4 due to ongoing triggers (e.g., a civilian walking in her building with a weapon), difficulty getting her housing transfer paperwork approved, and her recent breakup. Due to her elevated distress, the clinician and Assata decided to suspend the treatment content on cognitive restructuring and instead provide present-focused support for her distress, discussing coping strategies, problem solving (e.g., community resources), and exploring the potential for hospitalization (she went to see a psychiatrist after the session).

Although Assata and the clinician spent the first half of Session 5 on providing support and problem-solving for ongoing stressors, they spent the second half focusing on racial discrimination and Assata was able to weigh the pros and cons of various coping strategies. During that discussion Assata shared a racial trauma she experienced and talked about the importance of seeking support, containing her emotions in the moment, and focusing on herself/goals despite discrimination. Similarly, Assata was engaged during the Session 6 discussions about HIV discrimination/stigma, shared relevant examples, and weighed the pros and cons of various coping strategies (e.g., seeking support, HIV nondisclosure).

In Session 7 Assata and the clinician discussed gender roles for women, including self-silencing and not voicing one’s thoughts or feelings to maintain harmony, and sacrificing one’s needs to care for others. These resonated with Assata as she was struggling to communicate her thoughts and feelings to providers at a nonprofit organization and her Alcoholics Anonymous sponsor. Assata talked about learning (via the emphasis on self-care) to put herself first and stand up for her needs in relationships with intimate partners, children/grandchildren, and providers. For instance, she spoke about asserting herself with her daughter, who made disrespectful comments at times. Via a brief role-play the clinician and Assata practiced how to communicate assertively to a provider Assata planned on speaking with after session.

Following Session 7, Assata called and told the clinician that she wanted to stop the study because she was busy working and searching for housing, and as a result felt overwhelmed. The clinician and Assata discussed the pros and cons of taking a break from therapy and together concluded that Assata would stop her participation for now, but call back if and when she was ready. Assata called back 6 weeks later to continue in the study.

Throughout Sessions 8 through 10 Assata was able to reflect on evidence of her resilience, review skills learned in the treatment, as well as draft a relapse prevention plan. In Session 8, Assata spoke about experiencing medication fatigue (tired of taking the medication), especially in the context of searching for new housing and working. However, she was able to recall and, with the help of the clinician, articulate reasons why she needed to remain adherent (e.g., staying alive) and ways to strike a balance between work, school, and self-care activities.

Outcome Data

With ongoing stressors, Assata attended Sessions 1 to 7 every 2 weeks, and Session 8 occurred 6 weeks after Session 7. She also did not consistently complete work outside of the sessions related to the treatment (e.g., self-care activities, survival story). Due to a combination of the traumatic event (the shooting) that occurred during the course of the treatment, ongoing stressors, and Assata’s avoidance in processing her past trauma(s), her PTSD symptoms fluctuated (peaked after the shooting) throughout the treatment (see Figures 1 and 2 and Table 2). Therapeutically, Assata’s avoidance of in-depth processing of her past traumas may have been adaptive because doing so, even in a supportive treatment, may have increased her distress and taxed her ability to cope with the ongoing stressors and recent trauma. However, by the 6-month follow-up her PTSD symptoms on the DTS were lower than at baseline. Assata’s ART adherence began at 100% at baseline and was at or above 80% at every visit except one (76%). Her point of lowest adherence came after the shooting in her building (see Figures 1 and 2 and Table 2). By Session 10 and at her 3- and 6-month follow-up visits her adherence was back at 100%. Information on her HIV viral load at both 3- and 6- month follow-ups were not available in her medical records.

Case Study 5

Toni was a 47-year-old African-American woman who was married, currently unemployed, received SSDI, and in search of a new apartment. At baseline, Toni reported discontent with her marriage due to the absence of sexual intimacy and communication, frustrations with the housing search process due to gentrification-related rent increase and a lack of affordable housing in communities she grew up in and wanted to live, and struggles with building healthy relationships with her adult children as a result of strains imposed by periods of incarceration for both Toni and her children. Toni reported a history of several traumatic events including incarceration (self-defined as trauma), verbal abuse (especially in childhood by her mother), childhood sexual abuse, physical abuse, witnessing domestic violence as a child, and intimate partner violence as an adult. She noted that all of the traumas continued to have an impact on her life. Toni could not choose one trauma to focus on, but she scored 73 on the DTS, which is above threshold PTSD symptoms. Toni’s HIV medication adherence at baseline was 84% and she had a detectable viral load within the past 6 months. She was prescribed 1 ART pill to take twice per day and another pill to take once per day. It is noteworthy that Toni met for heroin and marijuana substance use dependence within the past 12 months and reported marijuana use three times per month and heroin use daily. At baseline she had been abstinent from heroin for 6 weeks.

Course of STEP-AD

The Life-Steps session highlighted barriers to Toni’s medication adherence, such as negative thoughts and emotions, side effects, forgetfulness, HIV stigma, and relapsing on substance (i.e., heroin). Toni explained that she had several negative cognitions/emotions around ART: “I don’t like it, it’s shameful . . . reminds me that I have HIV, is it poisonous, what is it doing to my liver.” However, Toni also articulated reasons for taking ART, including increasing her lifespan, being at peace with herself, being around for her children and grandchildren, setting a good example for her grandchildren, and living to experience a loving relationship. Given that substance use was noted as a barrier, time was also spent discussing coping strategies and resources to continue on her sobriety journey.

Toni was excited to learn about the treatment model provided in Session 2 and shared several experiences that resonated with the model (e.g., feelings of low self-worth stemming from her trauma histories and racism). The clinician provided psychoeducation on the impact of trauma and Toni shared that she continued to struggle with many PTSD symptoms (e.g., hypervigilance, difficulty concentrating, flashbacks, dreams). Her primary goal for the course of the treatment was to take her ART medication at the same time each day, start doing physical exercises, and reduce instances of self-defined “overeating.” Toni generated/selected self-care activities to do for between-sessions homework (e.g., massages, do hair and nails, and go shopping). Toni understood the rationale for writing her survival story about her traumas and with the clinician she planned when and where she would write it as well as strategies to use (e.g., take multiple breaks as needed, engage in a self-care activity immediately after).

In Session 3 Toni shared that she did not write her survival story because of difficulty finding housing and relationship stressors, which led to two instances of heroin use. In addition, Toni shared that the thought of revisiting her trauma in addition to her ongoing stressors elicited “anger.” The clinician helped Toni to process the stressors and her emotions (i.e., anger, avoidance). After discussing the pros and cons of writing her survival story, Toni then agreed to write her survival story in session and the clinician stepped out of the room and provided her with privacy. Thereafter Toni read and discussed her survival story with the clinician. As part of this, the impact of cycles of trauma in her family, along with structural factors (poverty, racism), emerged. Similar to CPT, Toni rewrote her survival story between Sessions 3 and 4, adding details on emotions and negative cognitions, and was very engaged in Session 4, which focused on continuing to process the traumas, eliciting her trauma-related cognitions (especially in the context of ART adherence), and learning/practicing cognitive restructuring skills.

Although Toni continued to not complete most of the between-sessions homework (except for occasionally doing self-care activities), in Sessions 5 and 6, which focused on racial discrimination and HIV-related discrimination, she shared past and present experiences of racism and HIV. Toni also shared the coping strategies she uses now or used previously (e.g., self-advocacy, legal action, HIV nondisclosure) and insightfully discussed the pros and cons of various strategies. For instance, Toni shared how she recently had to obtain a copy of her birth certificate and it had the term “colored” on it, which she successfully advocated to have removed and replaced with “Black.” (In the 1960s the term “Black” replaced “colored” because of its negative association with slavery and Jim Crow.)

The Session 7 content on gender roles occurred at a time when Toni reported recent conflicts (e.g., arguments) with her adult children (who were staying in her current apartment) and her husband. Toni was therefore engaged in discussing gender role expectations (e.g., to self-silence, do what others need/desire, look pretty/sexy) from her adult children, husband, and others. Toni was able to talk about adaptive strategies she is trying to use now (self-advocacy, prioritizing the self, and engaging in self-care activities [e.g. she went to the beach]) instead of nonadaptive responses (e.g. self-blame, sacrificing for others).

Throughout Sessions 8 through 10, Toni reflected on evidence of her resilience, reviewed skills learned in the treatment (e.g., prioritizing self-care), and drafted a relapse prevention plan. However, in the background there was a traumatic event and major stressors that were associated with increased PTSD symptoms and were discussed for the first portion of each session. Toni was choked by her husband during a fight at home and as a result he was arrested and incarcerated. In addition, Toni relocated from her familiar neighborhood to another area. As a result of these stressors there was a 6-week gap between Sessions 9 and 10.

Outcome Data

The treatment was delivered over the course of 7 months instead of 3 months because of Toni’s struggles with finding new housing, domestic violence resulting in the arrest of her husband and separation, and transportation difficulties when she eventually relocated to a town further away from the study site. Also, a portion of each session was spent processing her current stressors and problem solving (e.g., safety planning following domestic violence, discussing housing resources). Nonetheless, Toni was engaged as the clinician and she discussed content specifically intended for the treatment. In addition, Toni often did not complete the homework between sessions (e.g., self-care activities, survival story) or practice how to challenge her negative thoughts. As depicted in Figures 1 and 2 and Table 2, by the acute study visit when she finished the treatment at 7 months from baseline (labeled as 3 month follow-up) and the second follow-up visit at 10 months from baseline (labeled as 6 month follow-up), Toni had an improvement in ART adherence as well as a decrease in her PTSD symptoms. In addition, Toni reported ongoing sobriety from heroin. Her medical records did not include information on HIV viral load near her 3-month follow-up and near her 6-month follow-up her viral load was detectable at a level close to her baseline viral load.

Discussion

Five Black women with HIV, histories of trauma, and suboptimal adherence (< 80%) and/or detectable HIV viral loads within the past 6 months completed an open pilot trial of the 10-week STEP-AD treatment aimed at improving HIV medication adherence and decreasing trauma symptoms. The aim of the open pilot was to assess the preliminary acceptability and feasibility of the STEP-AD treatment, which was based on empirically validated CBT approaches for trauma and tailored for BWLWH, as well as consider ways that the treatment can be improved. All five women had lower PTSD symptoms on the DTS at the 6-month follow-up compared to baseline. Of the 4 women who were taking ART, 3 had higher ART adherence (all above 80%) at 3- and 6-month follow-ups compared to baseline, and 1 participant began with a 100% adherence and maintained that level of adherence at 3- and 6-month follow-ups. Medical record information on the women’s viral loads was unavailable for 4 of 5 women at the 3-month follow-up and unavailable for 1 of 5 women at the 6-month follow-up. For the 4 women with 6-month viral load data, 3 maintained a detectable viral load status and 1 woman’s status changed from detectable at baseline to undetectable at the 6-month follow-up. However, perhaps most important to note are the issues that were highlighted across the case studies and briefly synthesized below.

Themes Across Cases

Intersection of Trauma Reoccurrence and Unstable Housing

The first issue is the reoccurrence of trauma and considerable ongoing major life stressors. Both Assata and Toni were retraumatized during the course of the treatment, which increased their PTSD symptoms. Perhaps because they were involved in a trauma-focused treatment at the time of the new traumatic events their PTSD symptoms at follow-ups were lower than at baseline. Housing is the second issue that was particularly relevant for Toni and Assata. While both women had a physical apartment, both apartments were undesirable and one was unsafe. Toni was in search of an apartment that would have more space and be located in a familiar neighborhood; however, she was faced with the reality of high rent prices, gentrification, and racism when she approached potential landlords. Assata’s apartment building was the scene of a shooting and remained unsafe with illegal activities and visible weapons. For both women, finding new housing was a major stressor that they brought up at each visit. Although both women had case managers who were assisting them with housing searches, the process was taking considerable time.

The reoccurring trauma coupled with the housing issue negatively impacted Toni and Assata’s ability to attend sessions regularly, complete homework/practice skills between sessions, and finish the treatment on schedule. In addition, although the women were engaged in sessions, for ethical reasons and to prioritize their immediate needs, a large portion of several sessions was spent addressing their major stressors (problem solving around housing) and recent traumas (e.g., safety planning). Nonetheless, both Toni and Assata still appeared to benefit from the treatment in terms of lowered PTSD symptoms and staying adherent above 80%.

Toni's and Assata’s case suggest that ongoing structural issues such as housing and poverty, as well as continued exposure to trauma, may prevent women from maximizing the potential benefit of a treatment such as STEP-AD. However, the treatment may help women in similar situations to still adhere to ART in the midst of chaos by providing a space to revisit adaptive coping, focus on self-care, and engaging in adaptive problem solving. It is likely that some BWLWH and histories of trauma may benefit the most from STEP-AD when it is coupled with effective case management to address issues such as housing. Consistent with this point, the other three participants (Bell, Audre, and Maya), who appeared to benefit the most from the treatment in terms of the level of decline in PTSD symptoms and improvement in adherence, had stable/safe housing throughout the study and were not retraumatized.

Attendance and Skills Practice

In addition to not being retraumatized and residing in stable housing, Bell, Audre, and Maya also completed the majority of between-sessions homework, practiced skills, attended sessions on a regular basis, and completed the treatment on schedule. Therefore, session attendance, skills practice, and finding ways to maximize participants’ ability to do treatment-related work outside of the sessions is important.

Substance Use

Substance use history was another factor that became evident across 4 of 5 participants, including women’s efforts in maintaining sobriety. STEP-AD incorporates and discusses substance use as an unhelpful coping response to the various adversities and stressors the women face as well as promotes engagement in self-care activities (e.g., walking, reading) as strategies to address substance use (Daughters, Magidson, Schuster, & Safren, 2010). Nonetheless, a formal section of the treatment dedicated to substance use would be beneficial in future iterations of STEP-AD.

STEP-AD for ART Uptake

At the start of treatment, Audre was not taking ART and had a detectable viral load, but by the 6-month follow-up visit she began to take ART. She also experienced and maintained a reduction in her PTSD symptoms during the treatment and throughout follow-up visits. Although originally thought of as a treatment for BWLWH who were taking ART and struggling to adhere at an optimal level, it appears that STEP-AD might be applicable for women not yet on ART but who would be candidates for ART.

Future Directions

This treatment study, unlike a majority of CBT treatment trials, is working with participants with significant past and present life stressors and complex comorbidities as well as Black women who are often not represented in clinical trails (Spinazzola, Blaustein, & van der Kolk, 2005). As CBT treatments need to be disseminated to underserved populations, the examples provided here follow an evidence-informed treatment in the context of significant and ongoing life stressors, lending evidence for flexibility in delivering evidence-based CBT and matching treatment approaches to participants' ongoing needs.

Future iterations of this study should also directly assess HIV viral load at the follow-up periods, instead of reviewing participants’ medical records, in order to fully examine the potential impact of this intervention on HIV viral load status. A randomized control trial comparing STEP-AD to a control condition would be needed to evaluate the efficacy of STEP-AD and determine whether the results obtained are directly related to this intervention as developed or related to the time and interaction with study staff. Future efficacy data from an RCT may also inform whether case management after the STEP-AD intervention is needed to maintain long-term effects (e.g., reduced viral load). In addition, more process-focused research looking at changes in the client’s personal narratives and thoughts about the nature of the pilot intervention could also be beneficial in informing future directions for STEP-AD.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the case studies of five Black women living with HIV and histories of trauma who participated in the STEP-AD treatment provides support for the preliminary feasibility and acceptability of the treatment. However, some refinement may be needed (e.g., content on substance use, case management) to maximize the potential benefit of the treatment. In addition, a closer look at the process that took place during the intervention sessions may help to highlight mechanisms that facilitated change and inform ways to further enhance STEP-AD.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

A case series of a tailored CBT approach for Black women living with HIV

10-session treatment to improve medication adherence and decrease trauma symptoms

To enhance coping with race- and HIV- related discrimination and gender roles

Presents the cases of five Black women with HIV who completed the treatment

Treatment shows promise for improving adherence and decreasing trauma symptoms

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants, community stakeholders, and research staff, who gave their time and effort and made this research possible. The research reported in this publication and the principal investigator (Dr. Sannisha Dale) were funded by 1K23MH108439 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Preliminary work that informed the development of the treatment manual described was supported by a scholar award (PI Dr. Sannisha Dale) from the Harvard University Center for AIDS Research (HU CFAR National Institute of Health /National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease fund 2P30AI060354-11). Dr. Steven Safren was funded by grant K24 DA040489. The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Sannisha K. Dale, University of Miami and Massachusetts General Hospital

Steven A. Safren, University of Miami

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Amico KR, Harman JJ, Johnson BT. Efficacy of antiretroviral therapy adherence interventions: A research synthesis of trials, 1996 to 2004. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2006;41(3):285–297. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000197870.99196.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangsberg DR, Hecht FM, Charlebois ED, Zolopa AR, Holodniy M, Sheiner L, … Moss A. Adherence to protease inhibitors, HIV-1 viral load, and development of drug resistance in an indigent population. AIDS. 2000;14(4):357–366. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200003100-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart LM, Dale SK, Christian J, Patel K, Daffin GK, Mayer KH, Pantalone DW. Coping with discrimination among HIV-positive Black men who have sex with men. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 2017 doi: 10.1080/13691058.2016.1258492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart LM, Wagner GJ, Galvan FH, Klein DJ. Longitudinal relationships between antiretroviral treatment adherence and discrimination due to HIV-serostatus, race, and sexual orientation among African–American Men with HIV. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;40(2):184–190. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9200-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L, Belgrave FZ, Reisen CA. Gender roles, power strategies, and precautionary sexual self-efficacy: Implications for Black and Latina women's HIV/AIDS protective behaviors. Sex Roles. 2000;42(7):613–635. doi: 10.1023/A:1007099422902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brody LR, Stokes LR, Kelso GA, Dale SK, Cruise RC, Weber KM, … Cohen MH. Gender role behaviors of high affiliation and low self-silencing predict better adherence to antiretroviral therapy in women with HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDS. 2014;28(9):459–461. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody LR, Stokes LR, Dale SK, Kelso GA, Cruise RC, Weber KM, … Cohen MH. Gender roles and mental health in women with and at risk for HIV. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2014;38(3):311–326. doi: 10.1177/0361684314525579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Women, Gender, HIV by Group, HIV/AIDS, CDC. 2016 Mar 16; Retrieved May 31, 2016, from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/women/index.html.

- Cohen M, Deamant C, Barkan S, Richardson J, Young M, Holman S, … Melnick S. Domestic violence and childhood sexual abuse in HIV-infected women and women at risk for HIV. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:560–565. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.4.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MH, Cook JA, Grey D, Hanau LH, Levine AM, Wilson TE, … Young M. Medically eligible women who do not use HAART: The importance of abuse, drug use, and race. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(7):1147–1151. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor KM, Davidson JRT. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) Depression and Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale SK, Cohen MH, Kelso GA, Cruise RC, Weber KM, Watson C, … Brody LR. Resilience among women with HIV: Impact of silencing the self and socioeconomic factors. Sex Roles. 2014;70(5–6):221–231. doi: 10.1007/s11199-014-0348-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale S, Cohen M, Weber K, Cruise R, Kelso G, Brody L. Abuse and resilience in relation to HAART medication adherence and HIV viral load among women with HIV in the United States. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2014;28(3):136–143. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale SK, Weber KM, Cohen MH, Kelso GA, Cruise RC, Brody LR. Resilience moderates the association between childhood sexual abuse and depressive symptoms among women with and at-risk for HIV. AIDS and Behavior. 2015;19(8):1379–1387. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0855-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale SK, Pierre-Louis C, Bogart LM, O’Cleirigh C, Safren SA. Still I Rise: The need for self-validation and self-care in the midst of adversities faced by Black women with HIV. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2017 doi: 10.1037/cdp0000165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughters SB, Magidson JF, Schuster RM, Safren SA. ACT HEALTHY: A combined cognitive-behavioral depression and medication adherence treatment for HIV-infected substance users. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2010;17(3):309–321. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JR, Book SW, Colket JT, Tupler LA, Roth S, David D, … Feldman ME. Assessment of a new self-rating scale for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27(1):153–160. doi: 10.1017/S0033291796004229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]