Abstract

Suicide ideation and behavior among U.S. Hispanics has increased notably in the last decade, especially among youth. Suicide risk increases across generations of Hispanics, with risk greatest amongst U.S.-born Hispanics. Acculturative stress has been linked to increased risk for suicide ideation, attempts, and fatalities among Hispanics. Acculturative stress may increase suicide risk via disintegration of cultural values (such as familism and religiosity) and social bonds. Culturally-tailored prevention efforts are needed that address suicide risk among Hispanics. We propose a conceptual model for suicide prevention focused on augmenting cultural engagement among at risk Hispanics.

Keywords: United States Hispanics, suicide risk, suicide prevention

Introduction

As of 2010, the Hispanic1 population in the United States (U.S.) reached 50.5 million, making Hispanics the largest ethnic or racial minority group in the country [1]. The U.S. Hispanic population is expected to double by 2060 [2], constituting over 25% of the nation's population. Historically, compared to other ethnic or racial groups, Hispanics have been at decreased risk for suicide ideation, attempts, and death in the U.S. [3-5]. However, suicide rates among U.S. Hispanics have steadily risen since 2000 [5]. Despite the population size, suicide among Hispanics remains relatively understudied and little is known about how to prevent suicide in this population.

In 2015, suicide was the 11th leading cause of death among Hispanics of all ages (a rate of 5.84 per 100,000) in the U.S., but the 3rd leading cause of death among Hispanics aged 10-34 [5, 6]. Compared to Non-Hispanic Whites, Puerto Ricans and Mexican-Americans have fewer suicides annually per case of major depression [3]. Based on the National Institute of Mental Health funded Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiological Surveys (2001-2003), rough estimates place lifetime prevalence of suicide ideation and attempts among Hispanics around 11.35% and 5.11%, respectively [7]. Known as the “Latino Paradox,” Hispanic mortality – including suicide – is not as high as expected given degree of socioeconomic disadvantage [8]. This paradox may explain why suicide among Hispanics has not been seen as a pressing issue.

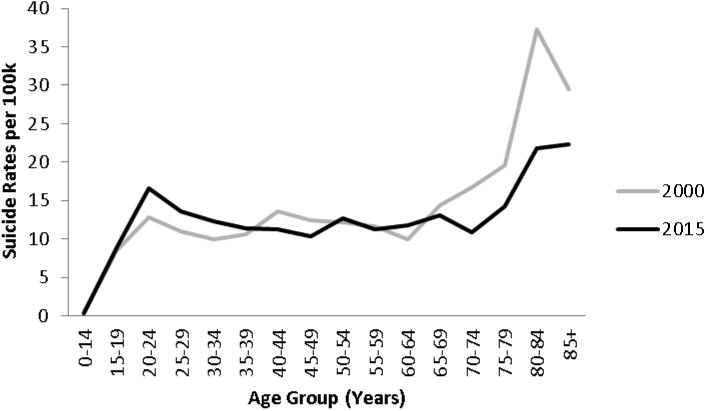

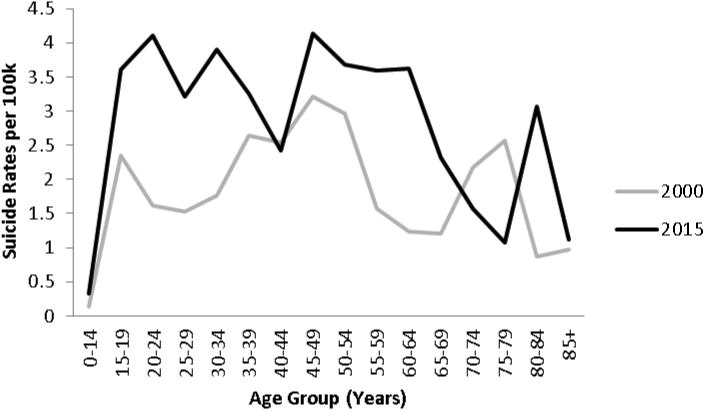

Recent research, however, has indicated a drastic rise in suicide rates among Hispanics in the U.S. in the last decade [9-11]. The rise in suicide rates among Hispanics seems to be attributable to Hispanic females, particularly among young adults. Mortality data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [5] suggests that, for Hispanic males, suicide rates have remained relatively stable from 2000 to 2015 across the lifespan, showing only a slight decrease (see Figure 1). However, during the same time frame, the rates among Hispanic females have increased by 50% overall, while increasing nearly 100% among young adults and those in mid-life (see Figure 2) [5].

Figure 1.

U.S. Hispanic male suicide rates by age group, 2000 vs. 2015, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [5]. Note: Y-axis differs from Figure 2.

Figure 2.

U.S. Hispanic female suicide rates by age group, 2000 vs. 2015, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [5]. Note: Y-axis differs from Figure 1.

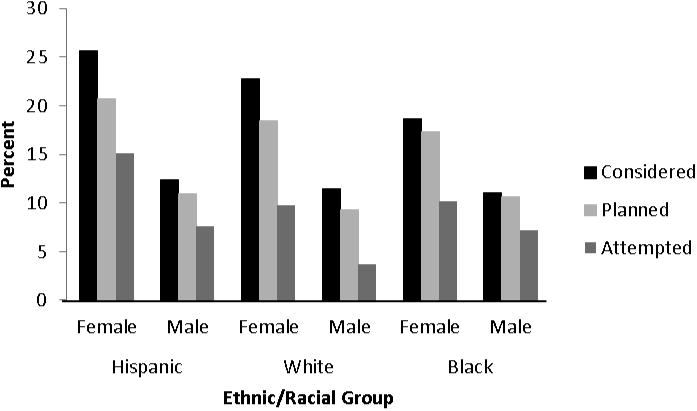

Although Hispanics still have lower rates of suicide compared to other ethnic or racial groups, Hispanic youth are significantly more likely to report suicide ideation and attempts than their Non-Hispanic counterparts [12]. Results from the 2015 national school-based Youth Risk Behavior Survey indicated that Hispanic youth (grades 9-12) in the U.S. were more likely to report seriously considering attempting suicide, making a suicide plan, and attempting suicide than their Non-Hispanic peers (see Figure 3) [12]. This trend is not new; previous research indicated that Hispanic adolescents in the early to mid-1990s reported significantly more frequent suicide ideation and attempts than their Anglo or European American counterparts [13-16]. The higher prevalence of ideation and attempts seems to be especially elevated among Hispanic adolescent females [12, 16]. Overall, these studies highlight the increased risk for suicide among Hispanic adolescents.

Figure 3.

Past year prevalence of serious suicide consideration, plans, and attempts among youth (grades 9-12) from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System [12].

Across Immigrant Generations

Effects of demographic, cultural, and economic characteristics on Hispanic suicide risk also vary across nationality, as well as native-born (i.e., U.S.-born) and immigrant (i.e., foreign-born) populations. Hispanics who have immigrated to or have family in the U.S. have higher rates of suicide behavior compared to Hispanics that have not immigrated or do not have family in the U.S., irrespective of migration selection bias [17]. Furthermore, Hispanics of Puerto Rican descent report the highest frequency of suicide ideation and attempts compared to Hispanics of Mexican or Cuban descent, as well as Non-Hispanic Whites2 [10, 18, 19]. The higher frequency of ideation and attempts among Puerto Rican adults compared to Non-Hispanic White adults [19] is notable, considering that Hispanic adults are generally at decreased risk for suicide. These studies highlight that Hispanics are not a monolithic group and that risk can vary across national-origin.

Foreign-born Hispanics in the U.S., across multiple national and regional cohorts, also tend to have lower rates of suicide than U.S.-born natives [4, 20]. Along these lines, lifetime prevalence of suicide ideation and attempts is also higher among U.S.-born Hispanics compared to foreign-born Hispanics [7, 21], especially when compared to foreign-born prior to migration [7]. Although some studies have found the opposite (i.e., immigrants at higher risk) [22, 23], this relationship may depend on the relative size of the Hispanic immigrant community in the area [22]. Specifically, Wadsworth and Kubrin [22] noted that immigrants were at greater risk for suicide than native-born counterparts in areas with smaller immigrant populations, whereas native-born Hispanics had a greater risk in areas with larger immigrant populations.

Immigrant generation status is also related to suicide attempts for Hispanic youth, such that second generation youth (i.e., U.S.-born Hispanics with immigrant parents) were almost three times more likely to attempt suicide than first generation (i.e., foreign-born) youth [24]. Suicide rates increase across Hispanic generations, with later generations of U.S.-born Hispanic youth (i.e., with U.S.-born parents) being around three and a half-times more likely to attempt suicide than first generation youth [24].

Protective and Risk Factors

Considering that Hispanics can face very stressful life conditions such as poverty, migration, cultural estrangements, and discrimination that may place them at risk for mental health problems [15], why are they generally at decreased risk for death by suicide? And why are specific subsets of Hispanics significantly at greater risk for suicide ideation and attempts?

Hispanic ethnic identity (i.e., perceived belonging to a particular ethnic/cultural group) may be closely tied with cultural values (e.g., religiosity, familism) that reduce risk for suicide despite the presence of mental health problems and socioeconomic stressors [25]. Greater degree of religious influence has been associated with decreased suicide ideation among Hispanic immigrants [26]. A recent study [23] found that religion significantly affected Hispanic suicide rates, with U.S.-born Hispanics benefitting from religious communities, regardless of denomination, and foreign-born Hispanics benefitting specifically from Catholicism. Hispanics also reported more perceived survival and coping abilities, responsibility to family, and moral objections to suicide than Non-Hispanic counterparts [9].

Familism, a social value that places the needs of the family before those of the individual, seems to be particularly related to suicide resiliency among Hispanics. A close relationship with family [9, 18], parental and familial connectedness and bonding [27], and positive relationships with parents [28] have been identified as protective factors for suicidality among Hispanics. Longer residence with family and greater familial support is also associated with fewer suicide attempts among Hispanic youth [29].

Wadsworth and Kubrin [22] suggest that a sense of ethnic or cultural integration and identity may help to attenuate feelings of alienation, isolation, and community disorganization among Hispanics, thus preventing suicide. Therefore, assimilation into mainstream culture (or acculturation), via the disintegration of traditional culturally and ethnically based belief systems and social networks, may lead to higher suicide rates among certain subsets of Hispanics [10, 21, 30]. Consistent with this, greater acculturation3 has been positively associated with suicide ideation (based on cross-sectional survey data) [31], attempts (based on longitudinal survey data) [32], and fatalities (based on CDC mortality and 2000 Census data) [22] among Hispanics. Acculturative stress—conflict or stress experienced by minority group members in the process of adapting to the majority group's culture—may lead to social group disintegration, role conflicts, and threats to the stability and durability of social relationships (e.g., loss of family structure and supports) [18]. Indeed, facets of familism (perceived familial obligation and viewing family as referents) decrease in importance among more acculturated Hispanics [33].

Certain aspects of acculturative stress, including exposure to discrimination, lower ethnic identity, greater family conflict, and a low sense of belonging, have been specifically associated with suicide ideation among Hispanic immigrants [25]. In a large, nationally-representative sample, researchers found that younger age at migration, longer time in the U.S., higher degree of English-language orientation, smaller Hispanic social network, lower Hispanic ethnic identity, and perceived discrimination were associated with increased lifetime risk for suicide ideation and attempts [34]. Similarly, social acculturative stress (i.e., quality of social relationships) and discrimination have been associated with over three times increased odds of suicide attempts among Hispanic emerging adults[35].

Suicide Prevention Interventions among Hispanics

The growing suicide risk among Hispanics is particularly concerning given that Hispanic youth report less favorable attitudes toward help-seeking [36] and Hispanics are less likely to utilize mental health services compared to the general population [37, 38]. Hispanic adults who report suicide ideation or attempts are also less likely than non-Hispanic Whites to have sought or received psychiatric services in the past year [39]. Furthermore, during a suicide crisis, Hispanics are less likely than non-Hispanics to use a crisis line [40].

Low mental health literacy, stigma, and beliefs about treatment may be barriers to mental health care for Hispanics [41]. Dueweke and Bridges [42] examined whether passive psychoeducation (via brochures) would improve suicide literacy, stigma, and help-seeking attitudes among Hispanic immigrants. Results indicated that although suicide literacy improved, stigma toward suicidal individuals and attitudes toward seeking help did not. It may be that more active and culturally-tailored approaches are needed to impact attitudes about suicide and help-seeking behaviors among Hispanics.

One such culturally-tailored prevention intervention is Familias Unidas, a family-based intervention designed to prevent and reduce risky behaviors (e.g., drug/alcohol use and risky sexual behavior) among Hispanic adolescents by improving family functioning. Familias Unidas consists of eight multi-parent group sessions focused on parenting-skills, followed by four family sessions. Familias Unidas has been shown to prevent and reduce conduct problems, risky behaviors, and internalizing symptoms (e.g., depression) among Hispanic adolescents [43-45]. Although not designed as a suicide prevention program, Familias Unidas has also significantly reduced suicide attempts among Hispanic adolescents with low levels of baseline parent-adolescent communication [46].

Problematically, a review of the literature revealed no culturally-tailored suicide prevention programs designed for Hispanics. Suicide prevention programs in Spanish are also lacking, which is concerning given that about 34% of Hispanics do not speak English proficiently in the U.S. [47]. Importantly, Hispanic youth and community leaders have suggested that culturally tailored depression/suicide prevention interventions for Hispanic youth should: (1) utilize multiple strategies (e.g., public awareness/educational outreach, skill-building activities) that are sustainable, (2) seek to raise awareness about depression in culturally meaningful ways, and (3) promote social connection and cultural enrichment activities [48].

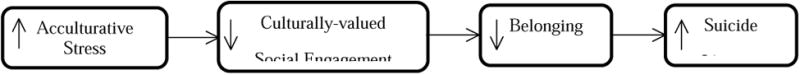

Thus, we suggest a conceptual model (Figure 4) for suicide prevention among Hispanics informed by the interpersonal theory of suicide [49]. The interpersonal theory of suicide [49, 50] proposes that low belonging (perceived connectedness to others) and perceived burdensomeness (perceived liability to others) are proximal risk factors for suicide by causing suicide ideation. Numerous studies support this premise [51]. Our conceptual model proposes that greater acculturative stress leads to decreased engagement (degree of participation) in culturally-valued social activities. Culturally-valued social activities are those involving interaction with others important to or prioritized by Hispanic culture, such as those related to familism, religion, and cultural traditions. Decreased engagement in culturally-valued social activities, in turn, decreases belonging and increases suicide ideation (see Figure 4). This model suggests that augmenting culturally-valued social engagement may reduce suicide risk among at risk Hispanics. Consistent with this model, research has found that, among Hispanic adolescent females, greater cultural involvement has been associated with better mother-daughter relationships and reduced likelihood of suicide attempts [52]. This model suggests that data indicating that Hispanic suicide varies depending on the size of the immigrant population [22] may be related to differences in cultural engagement and belonging.

Figure 4.

Conceptual model.

Conclusion

The variation of suicide risk among Hispanics highlights the need for additional culturally-relevant suicide research for this population. Estimates of suicide ideation, attempts, and fatalities may not be reliable, given that Hispanics face barriers to inclusion in research (e.g., language). Furthermore, more research is needed to understand how traditionally protective cultural-values (such as familism) influence suicide risk across the lifespan. For example, familism may place some individuals at risk as they age if they do not feel like they contribute to their family (burden).

The “Latino Paradox” means that suicide (and mortality) among Hispanics in general is not considered a health disparity and, thus, has not received greater attention. We believe that the need for suicide prevention research among Hispanics is imperative. We anticipate a large rise in suicide behavior among Hispanics as current high-risk cohorts of Hispanic adolescents reach midlife – a time of heightened risk [53] – in coming decades. Researchers have suggested that in order to reduce suicidality among Hispanics, common suicide risk factors (e.g., psychiatric problems) as well as culturally unique risk factors need to be addressed [25]. Family-based interventions may be beneficial for Hispanics [54], particularly those that capitalize on promoting cultural engagement and values.

The changing cultural demographics in the United States have important implications for suicide research. At the time of the 2010 U.S. Census, 16% of the population identified as Hispanic or Latino [1], a 43% increase since 2000. In light of this, and the increasing risk for suicide among Hispanics, there is a pressing need for the development of culturally-appropriate suicide assessment and prevention programs available in both English and Spanish. Preventing suicide among Hispanics across the lifespan must be considered a public health priority.

Highlights.

Hispanics are the largest ethnic/racial minority group in the United States.

Suicide behaviors have grown among Hispanics in the last decade, especially for females and youth.

Acculturation is associated with increased suicide risk among Hispanics.

Culturally-tailored interventions are needed to reduce suicide risk among Hispanics.

Footnotes

We use the term Hispanic throughout this article to refer to persons of Spanish-speaking origin or ancestry. Latino can be a broader term, referring to persons of Latin American origin or ancestry, including Portuguese and Brazilians. We note, however, that the two terms are often used interchangeably in the literature.

Those of Mexican descent had similar rates to Non-Hispanic Whites, with those of Cuban descent having significantly lower rates of suicide compared to those of Puerto Rican descent and Non-Hispanic Whites [19].

As measured by self-report measures of acculturative stress [31, 32] or an index representing metropolitan statistical area patterns of Hispanic immigration and cultural assimilation [22].

Declaration of Interest: Conflicts of interest: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ennis SR, Rio-Vargas M, Albert NG. The Hispanic population: 2010. 2010 Census Briefs. 2011 Retrieved from: http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf.

- 2.Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the size and composition of the U.S. population: 2014 to 2060. Current Population Reports. 2015 Retrieved from: http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf.

- 3.Oquendo MA, Ellis SP, Greenwald S, Malone KM, Weissman MM, Mann JJ. Ethnic and sex differences in suicide rates relative to major depression in the United States. Am J Psychiat. 2001 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorenson SB, Golding JM. Prevalence of suicide attempts in a Mexican-American population: Prevention implications of immigration and cultural issues. Suicide Life-Threat. 1988;18(4):322–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278x.1988.tb00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2017. Fatal injury reports, national, regional and state, 1981-2015. Retrieved from: http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/mortrate.html. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2017. Leading causes of death reports, 1981-2015. Retrieved from: https://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/leadcause.html. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borges G, Orozco R, Rafful C, Miller E, Breslau J. Suicidality, ethnicity and immigration in the USA. Psychol Med. 2012;42(6):1175–1184. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraido-Lanza AF, Dohrenwend BP, Ng-Mak DS, Turner JB. The Latino mortality paradox: a test of the “salmon bias” and healthy migrant hypotheses. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(10):1543–1548. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.10.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oquendo MA, Dragatsi D, Harkavy-Friedman J, Dervic K, Currier D, Burke AK, Grunebaum MF, Mann JJ. Protective factors against suicidal behavior in Latinos. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2005;193(7):438–443. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000168262.06163.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oquendo MA, Lizardi D, Greenwald S, Weissman MM, Mann JJ. Rates of lifetime suicide attempt and rates of lifetime major depression in different ethnic groups in the United States. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;110(6):446–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zayas LH, Lester RJ, Cabassa LJ, Fortuna LR. Why do so many Latina teens attempt suicide? A conceptual model for research. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75(2):275–287. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12**.Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Hawkins J, Queen B, Lowry R, Olsen EO, Chyen D, et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance - United States, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016;65(6):1–174. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6506a1. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/ss/ss6506a1.htm. An examination of population-based data on health-risk behaviors among youth in the United States from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (reporting period covered 09/2014-12/2015). Report provides a detailed summary of over 100 different health behaviors from national, state, and school district surveys conducted among students (grades 9-12). Summary includes information on suicide thoughts and behaviors among youth across different ethnic/racial groups, gender, and grades. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olvera RL. Suicidal ideation in Hispanic and mixed-ancestry adolescents. Suicide Life-Threat. 2001;31(4):416–427. doi: 10.1521/suli.31.4.416.22049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts RE, Chen YW. Depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation among Mexican-origin and Anglo adolescents. J Am Acad Child Psy. 1995;34(1):81–90. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199501000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tortolero SR, Roberts RE. Differences in nonfatal suicide behaviors among Mexican and European American middle school children. Suicide Life-Threat. 2001;31(2):214–223. doi: 10.1521/suli.31.2.214.21519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rew L, Thomas N, Horner SD, Resnick MD, Beuhring T. Correlates of recent suicide attempts in a triethnic group of adolescents. J Nurs Scholarship. 2001;33(4):361–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borges G, Breslau J, Su M, Miller M, Medina-Mora ME, Aguilar-Gaxiola S. Immigration and suicidal behavior among Mexicans and Mexican Americans. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(4):728–733. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.135160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ungemack JA, Guarnaccia PJ. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Cuban Americans. Transcult Psychiatry. 1998;35(2):307–327. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baca-Garcia E, Perez-Rodriguez MM, Keyes KM, Oquendo MA, Hasin DS, Grant BF, Blanco C. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among Hispanic subgroups in the United States: 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. J Psychiat Res. 2011;45(4):512–518. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh GK, Hiatt RA. Trends and disparities in socioeconomic and behavioural characteristics, life expectancy, and cause-specific mortality of native-born and foreign-born populations in the United States, 1979–2003. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(4):903–919. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fortuna LR, Perez DJ, Canino G, Sribney W, Alegria M. Prevalence and correlates of lifetime suicidal ideation and attempts among Latino subgroups in the United States. J Clin Psychiat. 2007;68(4):572–581. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wadsworth T, Kubrin CE. Hispanic suicide in US Metropolitan Areas: Examining the effects of immigration, assimilation, affluence, and disadvantage. Am J Sociol. 2007;112(6):1848–1885. [Google Scholar]

- 23*.Barranco RE. Suicide, religion, and Latinos: A macrolevel study of US Latino suicide rates. Sociol Quart. 2016;57(2):256–281. An examination of the influence of religion on suicide rates among Hispanic in the United States using CDC Multiple Cause-of-Death mortality and 2010 Census data. Highlights differences among native and foreign-born Hispanics on religious variables most associated with reduced suicide rates. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peña JB, Wyman PA, Brown CH, Matthieu MM, Olivares TE, Hartel D, Zayas LH. Immigration generation status and its association with suicide attempts, substance use, and depressive symptoms among Latino adolescents in the USA. Prev Sci. 2008;9(4):299–310. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0105-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25*.Fortuna L, Álvarez K, Ortiz ZR, Wang Y, Alegría XM, Cook B, Alegría M. Mental health, migration stressors and suicidal ideation among Latino immigrants in Spain and the United States. Eur Psychiat. 2016;36:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.03.001. A study examining factors associated with suicide ideation among Hispanic immigrants in the United States, as well as Spain. Highlights the role of specific aspects of acculturative stress (i.e., discrimination, ethnic identity, family conflict, and low belonging) and psychiatric disorders on lifetime and past month suicide ideation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hovey JD. Religion and suicidal ideation in a sample of Latin American immigrants. Psychol Rep. 1999;85(1):171–177. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1999.85.1.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borowsky IW, Ireland M, Resnick MD. Adolescent suicide attempts: Risks and protectors. Pediatrics. 2001;107(3):485–493. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Locke TF, Newcomb MD. Psychosocial predictors and correlates of suicidality in teenage Latino males. Hispanic J Behav Sci. 2005;27(3):319–336. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maimon D, Browning CR, Brooks-Gunn J. Collective efficacy, family attachment, and urban adolescent suicide attempts. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(3):307–324. doi: 10.1177/0022146510377878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zayas LH, Kaplan C, Turner S, Romano K, Gonzalez-Ramos G. Understanding suicide attempts by adolescent Hispanic females. Soc Work. 2000;45(1):53–63. doi: 10.1093/sw/45.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hovey JD. Acculturative stress, depression, and suicidal ideation in Mexican immigrants. Cult Divers Ethn Min. 2000;6(2):134–151. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.6.2.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vega W, Gil AG, Zimmerman R, Warheit G. Risk factors for suicidal behavior among Hispanic, African-American, and non-Hispanic white boys in early adolescence. Ethnic Dis. 1993;3(3):229–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sabogal F, Marín G, Otero-Sabogal R, Marín BV, Perez-Stable EJ. Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn't? Hispanic J Behav Sci. 1987;9(4):397–412. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perez-Rodriguez MM, Baca-Garcia E, Oquendo MA, Wang S, Wall MM, Liu SM, Blanco C. Relationship between acculturation, discrimination, and suicidal ideation and attempts among US Hispanics in the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiat. 2014;75(4):399–407. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gomez J, Miranda R, Polanco L. Acculturative stress, perceived discrimination, and vulnerability to suicide attempts among emerging adults. J Youth Adolescence. 2011;40(11):1465–1476. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9688-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36*.De Luca S, Schmeelk-Cone K, Wyman P. Latino and Latina Adolescents' help-seeking behaviors and attitudes regarding suicide compared to peers with recent suicidal ideation. Suicide Life-Threat. 2015;45(5):577–587. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12152. A study examining help-seeking attitudes and behaviors among Hispanic adolescents compraed to Non-Hispanics peers. Highlights the decreased likelihood of help-seeking among Hispanic adolescents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alegría M, Mulvaney-Day N, Woo M, Torres M, Gao S, Oddo V. Correlates of past-year mental health service use among Latinos: Results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):76–83. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cabassa LJ, Zayas LH, Hansen MC. Latino adults' access to mental health care: A review of epidemiological studies. Adm Policy Ment Hlt. 2006;33(3):316–330. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0040-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahmedani BK, Perron B, Ilgen M, Abdon A, Vaughn M, Epperson M. Suicide thoughts and attempts and psychiatric treatment utilization: Informing prevention strategies. Psychiat Serv. 2012;63(2):186–189. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Larkin GL, Rivera H, Xu H, Rincon E, Beautrais AL. Community responses to a suicidal crisis: Implications for suicide prevention. Suicide Life-Threat. 2011;41(1):79–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2010.00013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity—ASupplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 42*.Dueweke AR, Bridges AJ. The effects of brief, passive psychoeducation on suicide literacy, stigma, and attitudes toward help-seeking among Latino immigrants living in the United States. Stigma Hlth. 2017;2(1):28–42. A study examining the effects of passive psychoeducation material (i.e., brochure) on improving suicide literacy, stigma toward suicidal individual, and help-seeking among Hispanic immigrants in the United States. Highlights the need for more active intervention approaches to improve stigma and help-seeking attitudes. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prado G, Pantin H, Briones E, Schwartz SJ, Feaster D, Huang S, Sullivan S, Tapia MI, Sabillon E, Lopez B. A randomized controlled trial of a parent-centered intervention in preventing substance use and HIV risk behaviors in Hispanic adolescents. J Consult Clin Psych. 2007;75(6):914–926. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prado G, Cordova D, Huang S, Estrada Y, Rosen A, Bacio GA, Jimenez GL, Pantin H, Brown CH, Velazquez MR. The efficacy of Familias Unidas on drug and alcohol outcomes for Hispanic delinquent youth: Main effects and interaction effects by parental stress and social support. Drug Alcohol Depen. 2012;125:S18–S25. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perrino T, Pantin H, Prado G, Huang S, Brincks A, Howe G, Beardslee W, Sandler I, Brown CH. Preventing internalizing symptoms among Hispanic adolescents: A synthesis across Familias Unidas trials. Prev Sci. 2014;15(6):917–928. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0448-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46**.Vidot DC, Huang S, Poma S, Estrada Y, Lee TK, Prado G. Familias Unidas' crossover effects on suicidal behaviors among Hispanic adolescents: Results from an effectiveness trial. Suicide Life-Threat. 2016;46(S1):S8–S14. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12253. A study examining the impact of Familias Unidas, a family-based prevention program for risky behaviors for Hispanic adolescents, on suicidal behaviors. Highlights the moderating effect of parental-adolescent communication quality at baseline on intervention effects. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ryan C. American Community Survey Reports. U.S. Census Bureau; Washington, DC: 2013. Language use in the United States: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 48**.Ford-Paz RE, Reinhard C, Kuebbeler A, Contreras R, Sánchez B. Culturally tailored depression/suicide prevention in Latino youth: Community perspectives. J Behav Health Ser R. 2015;42(4):519–533. doi: 10.1007/s11414-013-9368-5. A qualitative study using focus groups with Hispanic youth and community leaders to inform the development of culturally-tailored depression/suicide prevention programs for Hispanic youth. Highlights the importance of community-based participatory research in intervention development for underserved/minority populations. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Joiner TE. Why People Die By Suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev. 2010;117(2):575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Joiner TE, Ribeiro JD, Silva C. Nonsuicidal self-injury, suicidal behavior, and their cooccurrence as viewed Through the lens of the interpersonal theory of suicide. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2012;21(5):342–347. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zayas LH, Hausmann-Stabile C, Kuhlberg J. Can better mother-daughter relations reduce the chance of a suicide attempt among Latinas? Depress Res Treat. 2011;2011:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2011/403602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Phillips JA, Robin AV, Nugent CN, Idler EL. Understanding recent changes in suicide rates among the middle-aged: Period or cohort effects? Public Health Rep. 2010;125(5):680–688. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zayas LH, Pilat AM. Suicidal behavior in Latinas: Explanatory cultural factors and implications for intervention. Suicide Life-Threat. 2008;38(3):334–342. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.3.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]