Abstract

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are rare tumors of gastrointestinal (GI) tract with mesenchymal cell origin. Extragastrointestinal stromal tumors (EGISTs) are unusual tumors that exhibit the same immunohistochemical and genetic abnormalities as GISTs and most commonly affect the omentum and mesentery. EGISTs of the pelvis and the female reproductive system are exceedingly rare and a frequent diagnostic pitfall. In this report, we present two cases of EGISTs along with a review of the literature.

Keywords: Extragastrointestinal stromal tumor, Vagina, Pelvic cavity

Highlights

-

•

All pelvic and vaginal EGISTs summarized

-

•

Presentation of pelvic EGISTs is nonspecific leading to delay in diagnosis.

-

•

Surgery +/− imatinib potentially curative for vaginal and pelvic EGISTs.

-

•

C-kit testing is essential to differentiate EGISTs from other gynecological tumors.

1. Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), which are classified as soft tissue sarcomas due to mesenchymal origin, comprise around 1% of all primary gastrointestinal cancers (Ivkoviæ et al., 2002). They are most common in the stomach (40 to 60%), jejunum/ileum (25 to 30%), duodenum (5%) and colorectum (5 to 15%) (Ivkoviæ et al., 2002). They are postulated to arise from a precursor cell of the interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC), also known as intestinal “pacemaker” cells, due to the expression of CD117 (c-kit) on both the tumor cells and the ICC. Most GISTs harbor c-kit gene mutation (most frequently in exon 9 and 11) or platelet derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA) gene that results in activation of a c-kit receptor tyrosine kinase, and subsequent cell proliferation induction and apoptosis inhibition (Yamamoto et al., 2004; West et al., 2004). Imatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has shown dramatic and sustained clinical benefit in GIST. Imatinib works by blocking the ATP-binding pocket required for phosphorylation and activation of the KIT and/or PDGFRA signaling pathways.

GISTs can be subserosal and extend into the abdominopelvic cavity or alternatively can arise from organs outside the luminal gastrointestinal tract and is termed extragastrointestinal stromal tumor (EGIST). Most commonly, EGISTs occur in the mesentery, omentum and retroperitoneum (Yamamoto et al., 2004; Miettinen et al., 1999). They have also been found to occur less commonly as free masses in the pelvic cavity (Peitsidis et al., 2008; Matteo et al., 2008; Angioli et al., 2009), bladder (He et al., 2014; Shin et al., 2011; KROKOWSKI et al., 2003), vagina (Weppler & Gaertner, 2005; Nagase et al., 2007; Ceballos et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2016) and the rectovaginal septum (Nasu et al., 2004; Lam et al., 2006; Melendez et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2009; Vázquez et al., 2012; Muñoz et al., 2013). In this report, two cases of EGISTs; one occurring in the vagina and one in the pelvic cavity are discussed, along with a brief review of EGISTs occurring in the pelvic cavity and vagina. The purpose of the review is to summarize clinical presentations, typical imaging, pathological findings, and treatment modalities.

2. Case 1

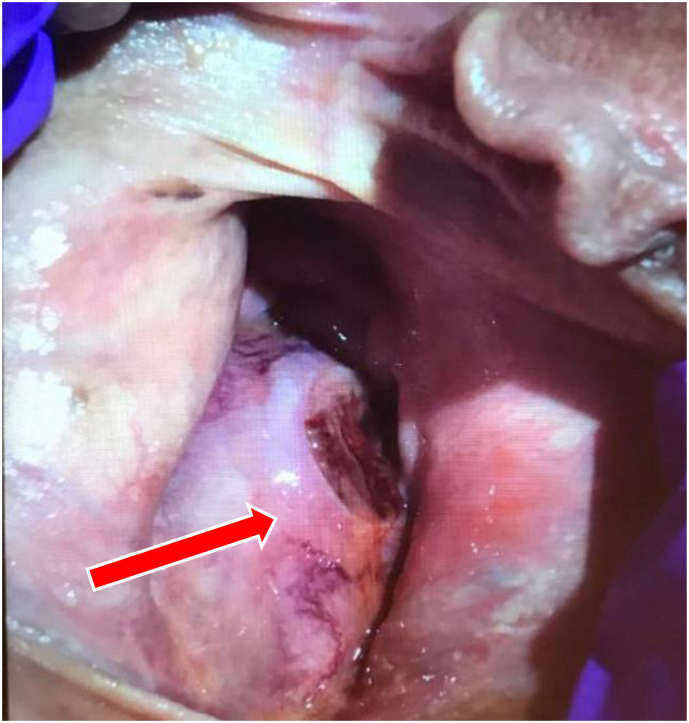

A 58-year-old female with a past medical history of a Bartholin's cyst presented with postmenopausal vaginal bleeding. On pelvic exam the patient was found to have a large intravaginal tumor that was spontaneously bleeding with a necrotic component (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Large Intravaginal mass (arrow) with necrotic component seen to be spontaneously bleeding on physical examination.

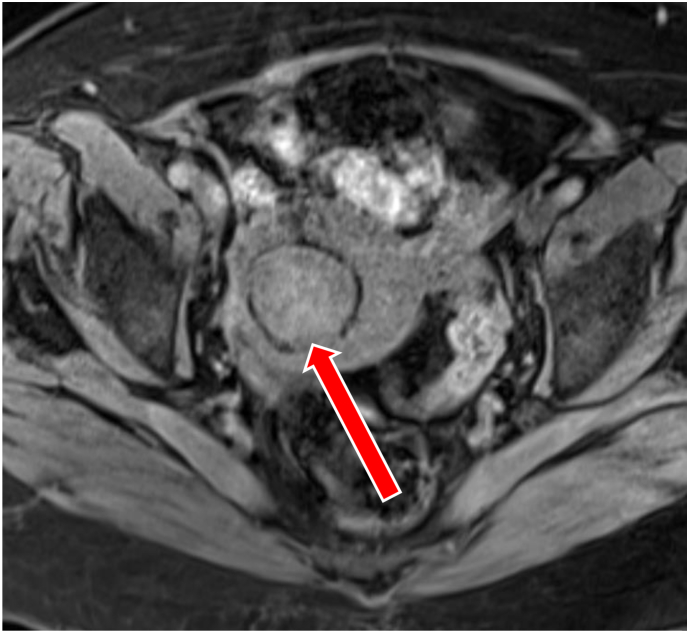

Transabdominal ultrasonography showed an intravaginal mass that appeared to communicate with the cervix. This raised suspicion of a malignancy and further imaging was obtained to evaluate the perineal area. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a 6.1 × 5.2 × 8.9 cm enhancing mass arising from the posterior wall of the vagina without definite involvement of the rectum, cervix, or pelvic floor musculature (Fig. 2). Proctoscopy showed that the tumor had not infiltrated into the rectum. The mass was biopsied and pathology revealed an EGIST, spindle cell type, with a mitotic rate of 4 per 50 high power fields (HPF). Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD117, DOG1, and caldesmon, but negative for desmin and smooth muscle actin. Molecular profiling of the tumor revealed an exon 11 KIT mutation. Given the size of the tumor and potential for invasion of surrounding organs the decision was made to initiate neoadjuvant treatment with imatinib for at least 6 months. After 3 months of imatinib therapy, there was favorable treatment response with shrinkage of tumor size to 3.6 × 3.6 × 5.9 cm compared with the above dimensions. The plan is to continue neoadjuvant therapy until surgery is deemed appropriate Fig. 3.

Fig. 2.

Magnetic Resonance Image of the pelvis showing an 8.9 cm enhancing mass (arrow) arising from the posterior wall of the vagina without definite involvement of the rectum, cervix, or pelvic floor musculature.

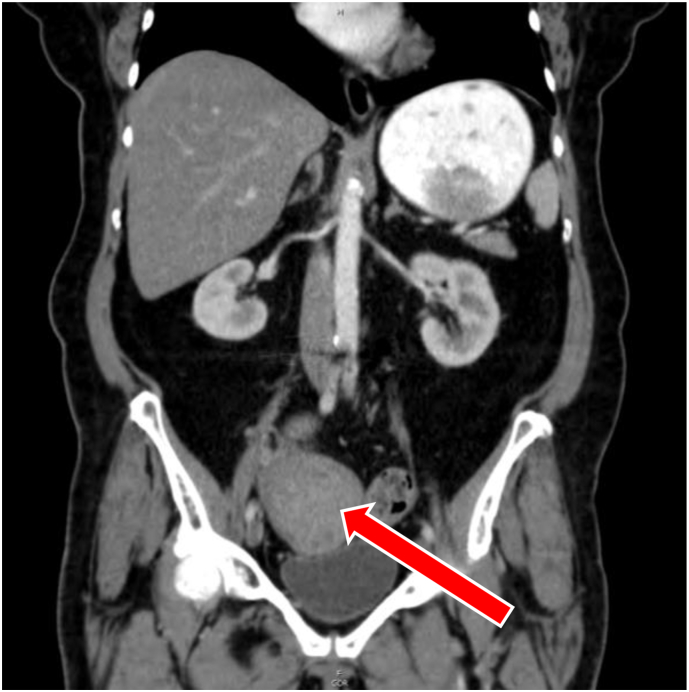

Fig. 3.

Computed tomography 8 cm well-circumscribed mass (arrow) in the right adnexal region which is in close association with the uterine fundus and adjacent bowel.

3. Case 2

A 73-year-old female with a past medical history of uterine fibroids presented to the emergency department with complaints of abdominal distension and suprapubic discomfort. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a large well-circumscribed mass near the right adnexa, in close association with the uterine fundus and adjacent bowel. Transvaginal ultrasonography was suspicious for malignant degeneration of uterine leiomyoma given the findings of bridging vessels between the tumor and the uterus.

These findings prompted an exploratory laparotomy which revealed an 8 cm tumor in the anterior cul-de-sac over the surface of the bladder. The mass was firmly attached to the bladder, anterior abdominal wall and loop of small bowel. The patient underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oopherectomy with partial bladder resection. The pelvic mass was ultimately diagnosed as an EGIST, spindle cell type, with 45 per 50 HPF mitotic rate (45/50HPF). Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD117, DOG1, and caldesmon, but negative for desmin and actin. Molecular profiling revealed an exon 11 KIT mutation.

The patient is currently undergoing adjuvant therapy with imatinib. After 8 months of therapy, there is no evidence of disease as seen on follow up imaging.

4. Discussion

Primary EGISTs originating from pelvic organs appear to be a diagnostic challenge and are frequently not on the clinician's differential diagnosis. Comprehensive literature review using PubMed, MEDLINE, and Google Scholar using the keywords: GIST, EGIST, vagina, and pelvis identified total of 37 cases of EGIST. After further screening to exclude EGISTs affecting the abdominal wall, seminal vesicle, omentum, liver, pancreas and prostate, 23 cases of pelvic organ EGISTs were identified. Five cases were of primary vaginal EGIST (Table 1) and 3 cases were of primary EGIST of the pelvic cavity (Table 2). Clinical, pathological and initial management features of previously published case reports (along with our cases) are summarized in the tables below in an attempt to reveal any similarities in presentation that may aid in the diagnosis of these rare tumors. (Refer to Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1.

Vaginal EGISTs.

| Case | Age | Presentation/Physical exam | Imaging | Pathology | IHC | Mutational analysis | Management | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E.H. Weppler & E.M. Gaertner (2005) (Weppler & Gaertner, 2005) | 66 | Postmenopausal bleeding, 8 cm posterior vaginal wall mass. | Poorly visualized on CT | Macroscopic: Irregularly shaped and light tan Microscopic: Spindle cell Mitotic rate: >5/50HPF |

Positive for: CD117, CD34, vimentin. | Not reported | Unresectable mass. Monotherapy with Imatinib. | Not reported |

| Liu QY et al. (2016) (Liu et al., 2016) | 41 | Painless, 8 cm mass in the posterior vaginal wall. | TVUS: Reported as cervical leiomyoma MRI: elliptical mass in the cervix and posterior vaginal wall with a clear margin consistent with leiomyoma. |

Macroscopic: Well-circumscribed mass surrounded by a fibrous capsule with hemorrhage and necrosis Microscopic: Spindle cell Mitotic rate: 25/50HPF | Positive for: CD117, CD34, DOG1. | KIT exon 11 | Surgical resection with adjuvant imatinib. | Follow-up after 5 months showed no recurrence or metastasis. |

| Ceballos et al. (2004) (Ceballos et al., 2004) | 75 | 5 cm posterior vaginal mass bulging into the introitus with intact overlying vaginal mucosa. | Pelvic imaging was unremarkable | Macroscopic: Well-circumscribed, tan, and lobulated mas, with a fleshy appearance and focal necrosis Microscopic: Spindle cell Mitotic rate: 12–15/50HPF | Positive for: CD117, vimentin, CD34, and h-caldesmon. | Not reported | Surgical excision with positive margins. | Follow-up at 10 months showed no recurrence. |

| S. Nagase et al. (2007) (Nagase et al., 2007) | 42 | 3.5 cm movable mass protruding into the vagina from the posterior vaginal wall. | Not reported | Macroscopic: Well-circumscribed mass with a fibrous capsule Microscopic: Spindle cell Mitotic rate: 1/50HPF | Positive for: CD34, CD117, and vimentin. | Not reported | Enucleation and excision without further treatment. | Follow-up at 4 years showed no recurrence. |

| S. Nagase et al. (2007) (Nagase et al., 2007) | 66 | Recurrent right vaginal wall mass (5 cm mass initially that was excised and embolized diagnosed as leiomyosarcoma. Two cm mass recurred 10 months later) | CT: well-circumscribed dense soft-tissue mass with no evidence of distant metastasis or lymph node swelling. | Macroscopic: not reported Microscopic: spindle cell Mitotic rate: 1–2/50HPF | Positive for: CD34, CD117, and vimentin. | KIT exon 11 | Surgical excision of 2 cm mass showing EGIST. (Review of previous mass 10 months prior confirms recurrent EGIST). Recurrence at 3 months treated with repeat excision and adjuvant imatinib (for 1 month). | No recurrence at 6-month follow up. |

| Our case | 58 | Postmenopausal bleeding. Large spontaneously bleeding intravaginal tumor with necrotic component | TVUS: intravaginal mass that appears to communicate with the cervix MRI: 8.9 cm enhancing mass arising from the posterior vaginal wall without definite involvement of the rectum, cervix, or pelvic floor musculature | Macroscopic: not reported Microscopic: spindle cell Mitotic rate: 4/50HPF | Positive for: caldesmon, C-kit (CD117) and DOG-1. | KIT exon 11 | Neoadjuvant imatinib. |

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; TVUS, transvaginal ultrasound; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; IHC, immunohistochemistry, HPF: high power field.

Table 2.

Primary pelvic EGIST.

| Case | Age | Presentation/Physical Exam | Imaging | Pathology | IHC | Mutational analysis | Management | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. Peitsidis et al. (2008) (Peitsidis et al., 2008) | 70 | Lower abdominal pain with feeling of bloating followed by acute abdomen. Uterus larger than normal, nonmobile, and painful during bimanual Palpation. | US: 10 cm hypoechoic enlarged uterus and mild collection of fluid in the pouch of Douglas | Macroscopic: Ruptured tumor in the pouch of Douglas Microscopic: epithelioid component and spindle cell component.Mitotic rate: 3/50HPF | Positive for: CD117, CD34, PDGFR, actin, vimentin. | Not reported | Urgent surgical intervention. Followed by low-dose imatinib for 1 year. | Follow up at 1 year, no sign of recurrence or metastasis |

| Angioli et al. (2009) (Angioli et al., 2009) | 38 | Abdominal distension Physical exam: large and compact pelvic mass extending to the periumbilical area was noted. | TVUS: heterogeneous and vascularized mass with predominantly solid components. MRI: 18 cm complex mass occupying the pelvis. Heterogeneous with necrotic areas originating from the peritoneum. | Macroscopic: white-grey containing hemorrhagic and necrotic areas Microscopic: elongated cells, arranged in fascicles (spindle cell) Mitotic rate: 17/50HPF | Positive for: CD117, vimentin, CD34, actin. | Not reported | Surgical resection of tumor followed by unspecified medical treatment. | Not reported |

| D. Matteo (2008) (Matteo et al., 2008) | 56 | Shortness of breath and abdominal distension. | CT: 30 cm heterogeneously enhancing mass with both cystic and solid components, arising from the pelvis. | Macroscopic: yellow-tan,firm and lobulated with cystic and hemorrhagic areas Microscopic: spindled and epithelioid morphology Mitotic rate: 18/50HPF | Positive for: CD117, CD34, vimentin. | Not reported | Surgical excision of two largest tumors. Followed by adjuvant Imatinib for metastatic deposits. | Follow-up at 6 months showed no residual tumor. |

| Our case | 73 | Abdominal distension, suprapubic pain. | CT: 8 cm well-circumscribed mass in the right adnexal region which is in close association with the uterine fundus and adjacent bowel | Macroscopic: tan, focally hemorrhagic, encapsulated mass Microscopic: spindle cell Mitotic rate: 45/50HPF | Positive for: CD117, DOG-1, caldesmon. | KIT exon 11 | Surgical resection. Followed by adjuvant Imatinib. |

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; TVUS, transvaginal ultrasound; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; IHC, immunohistochemistry; HPF, high power field.

5. Vaginal EGISTs

Our literature review identified 5 cases of vaginal EGISTs. All patients with vaginal EGISTs were postmenopausal and the tumor frequently presented itself as a mass protruding from the vaginal introitus. Average tumor size in largest diameter was 4.5 cm (range 2–8 cm). Vaginal EGISTs most commonly arose from the posterior vaginal wall. Case reports of EGISTs arising from the rectovaginal septum (Nasu et al., 2004; Lam et al., 2006; Melendez et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2009; Vázquez et al., 2012; Muñoz et al., 2013) suggested that these tumors arise from the rectovaginal septum or extended from the rectum, as opposed to arising from the vaginal wall stroma.

Pathological findings were certainly the most consistent across all of the cases. All tumors were well-circumscribed masses that may initially resemble leiomyomas. Spindle cell morphology (which is the most common morphology in GIST) was seen in 100% of the cases as well. As is typical with GISTs, CD117 was expressed on 100% of the cases. Desmin, smooth muscle actin (SMA), S100 were not expressed on any of the tumors further excluding the diagnosis of smooth muscle tumors and melanomas. Molecular profiling was performed on only 2 out of 5 cases. It revealed exon 11 KIT mutation similar to the case presented here. Vaginal EGISTs had a mitotic rate ranging between 1 and 25/50HPF and none were metastatic on presentation. This suggests that these tumors are indolent and have a low rate of metastatic potential. Four out of five patients were treated surgically. The unresectable tumor was treated with imatinib for an unspecified amount of time and no follow up was documented. Furthermore, out of the four cases where follow up was documented (Nagase et al., 2007; Ceballos et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2016), only one had a local recurrence which was subsequently treated with repeat surgical excision and adjuvant imatinib (Nagase et al., 2007; Ceballos et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2016). All four cases eventually went into complete remission without local or distant recurrence.

6. Pelvic EGISTs

Our literature review identified 3 reported cases of pelvic EGISTs. These tumors were consistently located in the rectouterine pouch (posterior cul-de-sac). Their clinical presentation and imaging findings are very similar to the presentation of ovarian malignancies. The most common presentation was that of abdominal distension and lower abdominal pain; however, they can also present as an acute abdomen requiring urgent surgical intervention (Peitsidis et al., 2008). All tumors were large in size, occupying the entire abdominopelvic cavity likely due to delay in diagnosis given the non-specific presenting symptoms. The average size was 16.5 cm (range 8–30 cm) in longest diameter. The behavior of pelvic EGISTs was variable, some tumors exhibited extensive metastatic deposits throughout the pelvic cavity while others were localized tumors. Exploratory laparotomy was consistently conducted to perform surgical staging and for tumor excision. After surgical resection, two out of three cases were treated with at least 6 months of imatinib with follow up revealing no recurrence or metastasis. The remaining case received unspecified medical therapy. Having a tissue diagnosis of EGIST before surgical intervention may be of clinical utility, largely because most of the tumors were large and could have potentially benefited from neoadjuvant imatinib. The presence of these tumors in the rectouterine pouch suggests that a transrectal ultrasound guided biopsy could be potentially feasible. As shown by Takano et al., diagnosis of a rectal GIST was made pre-operatively via an endoscopic needle biopsy (Takano et al., 2006).

Interestingly, no cases of males affected by pelvic cavity EGISTs have been described. Primary pelvic cavity EGISTs are an elusive entity, especially because it is difficult to determine the tumor's origin. Whether the tumors arise from the peritoneum or from the serosal surface of the bowel or mesentery remains inconclusive.

7. Conclusion

EGISTs affecting the female reproductive tract and the pelvic cavity are rare entities. Their presentation and imaging findings are nonspecific and this contributes to delays in diagnosis and treatment. Immunohistochemistry remains the most definitive method to diagnose EGISTs and differentiate them from other mesenchymal tumors. The current standard of care for EGIST is surgical resection as depicted in most of the cases. Neoadjuvant imatinib may be beneficial for locally advanced EGISTs because of the potential for shrinkage of the tumor prior to definitive surgery. Adjuvant therapy with imatinib should be considered for high risk EGIST (Eisenberg, 2013). Currently there is no data demonstrating the outcome and prognosis of EGISTs, however, it is safe to assume that the outcome for EGISTs is comparable to that of GISTs given the similarities in molecular alterations.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Angioli R., Battista C., Muzii L., Terracina G.M., Cafà E.V., Sereni M.I. A gastrointestinal stromal tumor presenting as a pelvic mass : a case report. Oncol. Rep. 2009:899–902. doi: 10.3892/or_00000301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos K.M., Francis J.-A., Mazurka J.L. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor presenting as a recurrent vaginal mass. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2004;128:1442–1444. doi: 10.5858/2004-128-1442-GSTPAA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg B.L. The SSG XVIII/AIO Trial. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. [Internet]. 2013;36(1):89–90. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e31827a7f55. http://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?sid=WKPTLP:landingpage&an=00000421-201302000-00016 Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He F., Fang Z., Zhu P., Huang W., Li L. Bladder extragastrointestinal stromal tumor in an adolescent patient: A case-based review. Mol. Clin. Oncol. [Internet] 2014:960–962. doi: 10.3892/mco.2014.366. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivkoviæ V. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs): definition, clinical, histological, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic features, and predictors of malignant potential and differential diagnosis. Arch. Oncol. 2002;10(4):267–271. [Google Scholar]

- KROKOWSKI M., JOCHAM D., CHOI H., FELLER A., HORNY H. Malignant Extragastrointestinal stromal tumor of bladder. J. Urol. [Internet] 2003;169(5):1790–1791. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000062606.13148.04. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0022534705636749 Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam M.M., Corless C.L., Goldblum J.R., Heinrich M.C., Downs-Kelly E., Rubin B.P. Extragastrointestinal stromal tumors presenting as vulvovaginal/rectovaginal septal masses. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. [Internet] 2006;25(3):288–292. doi: 10.1097/01.pgp.0000215291.22867.18. http://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?sid=WKPTLP:landingpage&an=00004347-200607000-00016 (Available from) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q.Y., Yun-Zhen Kan, Meng-Yang Zhang, Ting-Yi Sun, Kong L.-F. Primary extragastrointestinal stromal tumor arising in the vaginal wall: Significant clinicopathological characteristics of a rare aggressive soft tissue neoplasm. World J. Clin. Cases 2016 [Internet] 2016;4(4):118–124. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v4.i4.118. www.wjgnet.com (Available from) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matteo D., Dandolu V., Lembert L., Thomas R.M., Chatwani A.J. Unusually large extraintestinal GIST presenting as an abdomino-pelvic tumor. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2008;278(1):89–92. doi: 10.1007/s00404-007-0528-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melendez Marcos N., Revello Rocio, Cuerva Marcos J., De Santiago Javier, Zapardiel I. Misdiagnosis of an Extragastrointestinal stromal tumor in the rectovaginal septum. J. Low Genit. Tract Dis. 2014;18(3):66–70. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e3182a72156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen M., Monihan J., Sarlomo-Rikala M., Kovatich A.J., Carr N.J., Emory T.S. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors/smooth muscle tumors (GISTs) primary in the Omentum and mesentery: Clinicopathologic and Immunohistochemical study of 26 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1999;23(9):1109–1118. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199909000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz M., Echeverri C., Ramirez P.T., Echeverri L., Pareja L.R. Extragastrointestinal stromal tumor in the rectovaginal septum in an adolescent. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. [Internet]. 2013;5:67–69. doi: 10.1016/j.gynor.2013.05.004. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase S., Mikami Y., Moriya T., Niikura H., Yoshinaga K., Takano T. Vaginal tumors with histologic and immunocytochemical feature of gastrointestinal stromal tumor: two cases and review of the literature. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2007;17(4):928–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasu K., Ueda T., Kai S., Anai H., Kimura Y., Yokoyama S. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor arising in the rectovaginal septum. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2004;14(2):373–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1048-891x.2004.014230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peitsidis P., Zarganis P., Trichia H., Vorgias G., Smith J.R., Akrivos T. Extragastrointestinal stromal tumor mimicking a uterine tumor. A rare clinical entity. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2008;18(5):1115–1118. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin H.-S., Cho C.-H., Kum Y.-S. Extragastrointestinal stromal tumor of the urinary bladder: a case report. Urol. J. [Internet]. 2011;8(2):165–167. http://www.urologyjournal.org/index.php/uj/article/view/1033/559 Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano M., Saito K., Kita T., Furuya K., Aida S., Kikuchi Y. Preoperative needle biopsy and immunohistochemical analysis for gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the rectum mimicking vaginal leiomyoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2006;16(2):927–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez J., Pérez-Peña M., González B., Sánchez A. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor arising in the rectovaginal septum. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2012;16(2):158–161. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e31823b52af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weppler E.H., Gaertner E.M. Malignant extragastrointestinal stromal tumor presenting as a vaginal mass: report of an unusual case with literature review. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2005;15(6):1169–1172. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2005.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R.B., Corless C.L., Chen X., Rubin B.P., Subramanian S., Montgomery K. The novel marker, DOG1, is expressed ubiquitously in gastrointestinal stromal tumors irrespective of KIT or PDGFRA mutation status. Am. J. Pathol. [Internet] 2004;165(1):107–113. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63279-8. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Hidetaka, Oda Yoshinao, Kawaguchi Ken-ichi, Nakamura Norimoto, Takahira Tomonari, Tamiya Sadafumi, Saito Tsuyoshi, Oshiro Yumi, Ohta Yumi, Yao Takashi, Tsuneyoshi T. C-kit and PDGFRA mutations in Extragastrointestinal stromal. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2004;28(4):479–488. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200404000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Peng Z., Xu L. Extragastrointestinal stromal tumor arising in the rectovaginal septum: report of an unusual case with literature review. Gynecol. Oncol. [Internet]. 2009;113(3):399–401. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.02.019. (Available from) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]