Abstract

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are secreted by many cell types and are increasingly investigated for their role in human diseases including cancer. Here we focus on the secretion and potential physiological function of non-pathological EVs secreted by polarized normal mammary epithelial cells. Using a transwell system to allow formation of epithelial polarity and EV collection from the apical versus basolateral compartments, we found that impaired secretion of EVs by knockdown of RAB27A or RAB27B suppressed the establishment of mammary epithelial polarity, and that addition of apical but not basolateral EVs suppressed epithelial polarity in a dose-dependent manner. This suggests that apical EV secretion contributes to epithelial polarity, and a possible mechanism is through removal of certain intracellular molecules. In contrast, basolateral but not apical EVs promoted migration of mammary epithelial cells in a motility assay. The protein contents of apical and basolateral EVs from MCF10A and primary human mammary epithelial cells were determined by mass spectrometry proteomic analysis, identifying apical-EV-enriched and basolateral-EV-enriched proteins that may contribute to different physiological functions. Most of these proteins differentially secreted by normal mammary epithelial cells through polarized EV release no longer showed polarized secretion in MCF10A-derived transformed epithelial cells. Our results suggest an essential role of EV secretion in normal mammary epithelial polarization and distinct protein contents and functions in apical versus basolateral EVs secreted by polarized mammary epithelia.

Keywords: Extracellular Vesicles, Epithelial Polarization, Mammary Gland, Proteomics

Introduction

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are lipid membrane-enclosed particles secreted by virtually all cell types to excrete or transfer protein, RNA, and even DNA cargo to neighboring and distant cells, where they can influence physiological processes such as angiogenesis and migration. Most EV research has focused on the role of EVs in pathological settings such as cancer where they participate in the initiation, progression, and metastasis of cancer [1, 2]. However, despite the advances in our understanding of EVs in the context of disease, the physiological function of non-pathological EVs, particularly those secreted by normal epithelial cells, is poorly understood.

EV-mediated communication is an ancient process that can also be found in archaea, bacteria, and fungi [3] as well as mammals, suggesting that this mechanism has an important evolutionarily conserved role. However, our understanding of EV’s role in intercellular communication is complicated by their phenomenal diversity. The same cell can secrete many subtypes of EVs based on their size and origin, ranging in size from the most commonly studied exosomes, which are 30–100 nm in diameter and are formed from intraluminal budding of endosomes, to large oncosomes, which can be over 1 μm and are formed from plasma membrane blebbing [4]. Furthermore, the compositions of these EVs undergo dynamic shifts in response to different cellular stresses and signals including hypoxia [5–11], acidity [12], and senescence [13–15], reflecting the ability of EVs to respond and adapt to alterations in the microenvironment and cellular homeostasis. Perhaps the most striking observation in EV heterogeneity is the diversity of EVs secreted under the same conditions by the same cell into different physiological compartments.

Epithelial cells are highly polarized with distinct apical and basolateral domains which serve as the boundary between the epithelial cell and different physiological microenvironments. This system can be modeled in vitro by culturing epithelial cells on top of transwell inserts. If the cells are seeded at high confluency they can form electrically tight confluent monolayers over time which can be monitored by assessing trans-epithelial electrical resistance (TEER) or diffusion of phenol red. Damage to the monolayer or incomplete polarization lowers the difference in electrical resistance between the upper and lower wells, as a result TEER has become a gold standard for monitoring monolayer integrity. Early studies using this system have demonstrated that EVs secreted by intestinal epithelial cells containing apical or basolateral markers have differences in their protein composition [16, 17], suggesting that EVs shed into the apical and basolateral spaces may be functionally distinct. In order to help standardize the methods used for studying EVs, the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV) proposed several proteins as markers for EVs including tetraspanins such as CD63 and ESCRT (the endosomal sorting complex required for transport)-related proteins such as TSG101 [18]. Polarized MDCK cells secrete CD63-enriched EVs from their apical side, and TSG101-enriched EVs from their basolateral side [19], hinting that the general EV markers used by the research community may be marking specific populations of vesicles selectively secreted at specific membrane domains. This is consistent with the finding that EpCAM-containing EVs, which are presumably of apical origin, are enriched in the classical apical trafficking molecules CD63 in EVs secreted from colon carcinoma cells [16, 20]. It is important to note that enrichment of certain protein markers in either apical or basolateral EVs could be context-specific. For example, TSG101 has also been shown to be enriched in apical EVs from porcine retinal pigment epithelial cells [21]. The Drosophila ortholog of TSG101 is found to alter the localization of the apical determinant Crumbs in Drosophila eyes [22], suggesting its trafficking to the apical compartment.

Distinct loading mechanisms for apical versus basolateral cargo have been suggested. Polarized secretion of EVs allows for targeted delivery of specific EV populations to recipient cells as a result of the organized tissue architecture. For instance, αB Crystallin is selectively loaded into apical EVs secreted by retinal pigment epithelial cells. This allows them to deliver αB Crystallin to the apically located photoreceptors to protect them from oxidative stress [23]. Due to the structure of epithelial tissue, cells are often positioned so that the apical and basolateral sides of the cell are in contact with different cell types. Polarized secretion of EV populations would allow the cell to coordinate with each of these cell types. However, EV research is often performed on cells grown in two dimensions on tissue-culture plastic at sub-confluent densities in which EVs from various compartments are co-isolated [24, 25], making functional characterization of these vesicles extraordinarily difficult.

In this study, we determined the protein composition of apical and basolateral EVs secreted by polarized mammary epithelial cells to explore the potential physiological role of EVs in the mammary gland, which may shed light on the effect of dysregulated EV secretion during the loss of polarity and malignant transformation of epithelial cells.

Results

Polarization of mammary epithelial cells and collection of EVs

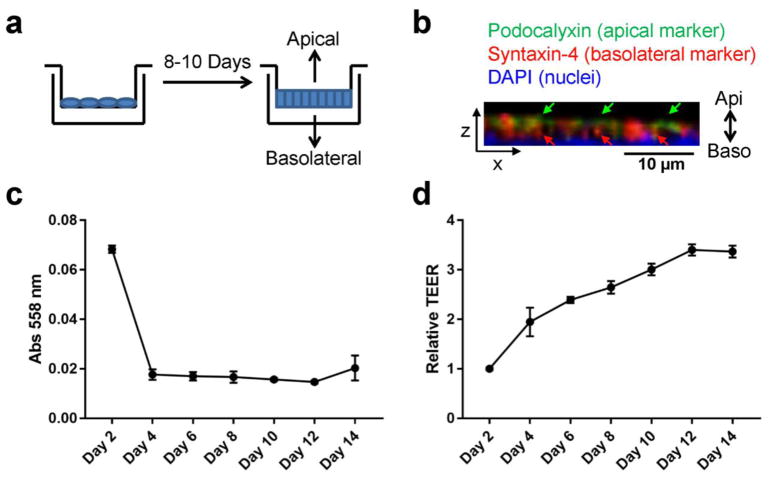

To collect EVs secreted from the apical and basolateral compartments of mammary epithelia, MCF10A human mammary epithelial cells were seeded onto transwells with 0.4 μm pore polycarbonate membrane insert and allowed to polarize for 8–10 days before conditioned medium (CM) collection from the upper well (for apical EVs) and the lower well (for basolateral EVs) (Fig. 1a). Immunostaining of the monolayer following CM collection demonstrated apical staining of Podocalyxin and basolateral staining of Syntaxin-4, indicating formation of apical-basolateral polarity (Fig. 1b). The integrity of the monolayer was measured every other day by diffusion of phenol red and TEER. MCF10A cells formed a tight monolayer with minimal diffusion of phenol red from the upper well to the lower well by day 4 and TEER measurements plateaued around day 12 (Fig. 1c, d). We chose to collect EVs from day 8 and day 10 to avoid those secreted from cells that were not fully polarized.

Fig. 1. Polarization of mammary epithelial cells.

(a) Transwell system for the polarization of mammary epithelial cells and collection of apical and basolateral EVs. (b) Immunofluorescence assay of polarized MCF10A cells showing polarized expression of Podocalyxin (an apical marker) and Syntaxin-4 (a basolateral marker). DAPI staining indicates the nuclei. Z-stack images are reconstructed in 3D and the XZ-view is shown. Green and red arrows indicate apical staining of Podocalyxin and basolateral staining of Syntaxin-4, respectively. (c) Time course for diffusion of phenol red from the upper chamber to the lower chamber of MCF10A transwell culture. (d) Time course of trans-epithelial electrical resistance (TEER) from MCF10A cells grown on 10-cm transwell filters.

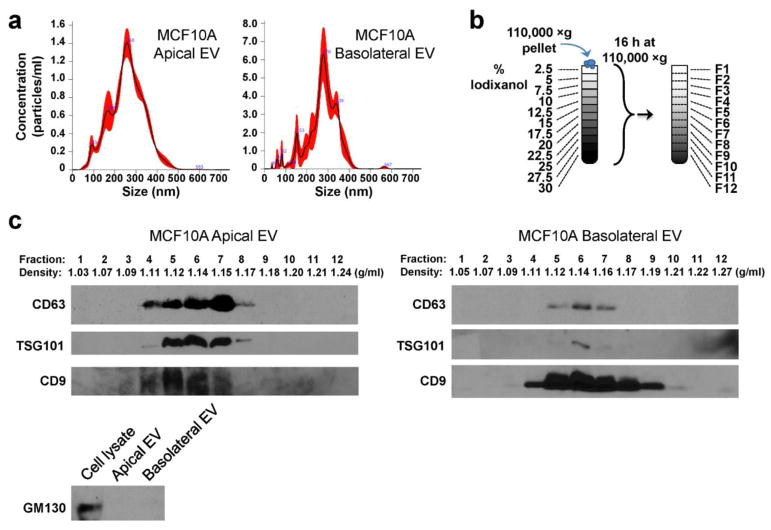

EVs were isolated from CM collected from the upper (apical EVs) and lower (basolateral EVs) chambers by ultracentrifugation and characterized by nanoparticle tracking analysis, indicating heterogeneous populations of vesicles varying in size and possibly representing single and aggregated exosomes as well as other types of vesicles such as microvesicles (Fig. 2a). The EVs were further characterized by OPTIPREP density gradient centrifugation and Western blotting for EV markers. Fractions 5–7 corresponding to densities 1.12–1.15 g/ml, around the density of exosomes, were most enriched in the EV markers CD63 and TSG101 in MCF10A apical and basolateral EVs (Fig. 2b, c). TSG101 was primarily found at 1.14 g/ml in MCF10A basolateral EVs and also from apical EVs (Fig. 2c). In both samples CD9 was found in a greater range of fractions, indicating that it marks a broad range of EV subpopulations. GM130, a Golgi marker and negative control for EV proteins, was undetectable in both apical and basolateral EVs.

Fig. 2. Characterization of EVs.

(a) EVs pelleted at 110,000 ×g were analyzed by nanoparticle tracking analysis. The black line indicates mean, whereas the red shaded area indicates SEM. (b) A schematic representation of the gradient separation procedure to further characterize the 110,000 ×g pellets. (c) Western blot and density measurement of fractions collected from gradient separation or unfractionated EV.

EV secretion is required for the establishment of epithelial polarity

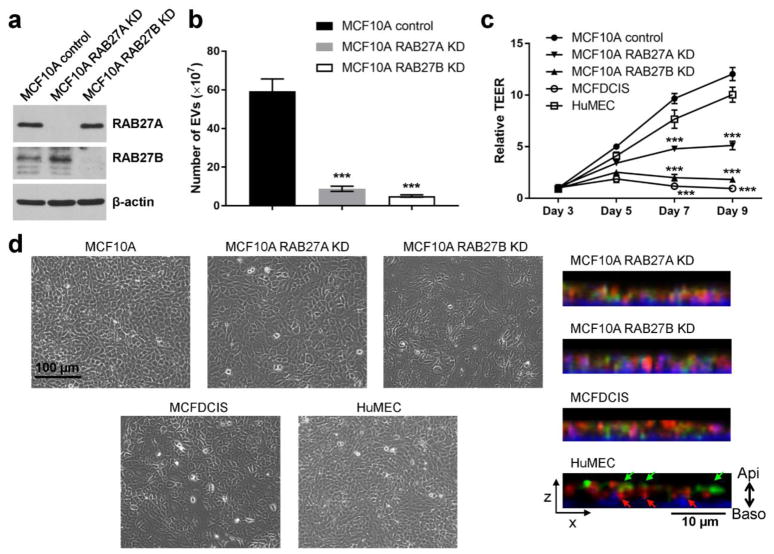

In order to understand potential functions for EVs secreted from mammary epithelial cells we generated MCF10A lines with stable knockdown of RAB27A or RAB27B (RAB27A KD and RAB27B KD, respectively; Fig. 3a). Both lines with RAB27 gene knockdown had significantly decreased EV secretion compared to the control MCF10A cells (Fig. 3b). When cultured on a transwell filter, both RAB27A KD and RAB27B KD cells had significantly lower TEER compared to control MCF10A cells (Fig. 3c), suggesting that EV secretion is important for the formation of polarity. Primary human mammary epithelial cells (HuMECs) also formed polarity on a transwell filter over a time course similar to MCF10A cells. In contrast, epithelial polarity was disrupted in MCF10A-derived MCFDCIS cells (Fig. 3c). The MCFDCIS cells are derived from a xenograft lesion originating from the premalignant MCF10AT cells (HRAS-transformed MCF10A cells) that were injected into immune-deficient mice, and form comedo ductal carcinoma in situ-like lesions that spontaneously progress to invasive tumors [26, 27]. Compared to MCF10A and HuMECs, the RAB27 KD cells and MCFDCIS cells displayed altered morphology including enlarged cell size and a less packed monolayer, as well as misdistributions of the apical and basolateral markers Podocalyxin and Syntaxin-4 (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3. EV secretion is required for the establishment of epithelial polarity.

(a) Western blot showing indicated protein levels in MCF10A control and RAB27 KD cells. (b) Numbers of EVs secreted by equal number of indicated cells were determined by nanoparticle tracking analysis. *** P < 0.001 compared to the MCF10A control cells. (c) MCF10A (control or RAB27 KD), MCFDCIS, and HuMEC cells were seeded on 24-well transwell inserts and TEER was measured over the indicated time course. *** P < 0.001 compared to the MCF10A control cells. (d) Left: Phase contrast images of indicated cells grown on tissue culture dishes. Right: The XZ-view of reconstructed Z-stack images showing the immunofluorescence staining of Podocalyxin (green) and Syntaxin-4 (red) in cells grown on filters. DAPI staining (blue) indicates the nuclei. Green and red arrows indicate apical staining of Podocalyxin and basolateral staining of Syntaxin-4, respectively.

Apical and basolateral EVs display different functions in cell polarity and migration

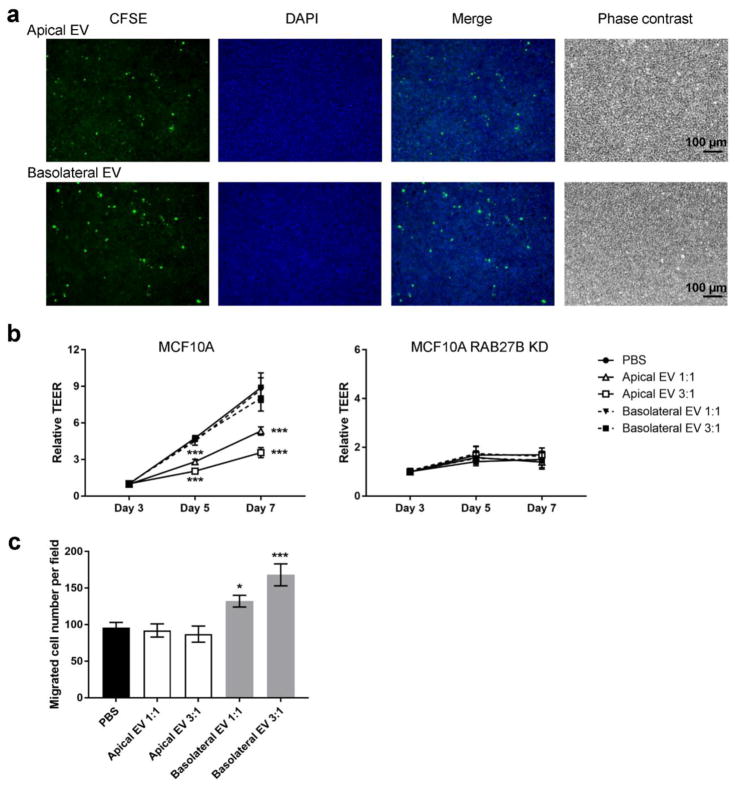

The disruption of epithelial polarity in MCF10A RAB27 KD cells could be due to the potential function of EVs to either intercellularly transfer cargo essential to facilitate epithelial polarization, or remove certain molecules that would otherwise hinder polarization. To examine these two different possibilities, we isolated apical and basolateral EVs from polarized MCF10A cells to examine their effect on polarity formation. The isolated EVs were added to transwell inserts containing unpolarized MCF10A cells seeded 1 day prior to treatment and polarization was monitored by TEER. Internalization of EVs was confirmed by incubating fluorescently labeled EVs with MCF10A cells grown on filters and detecting the fluorescence after 24 hr in the recipient cells (Fig. 4a). Interestingly, addition of apical but not basolateral EVs inhibited TEER at day 5 and 7 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4b). Neither types of EVs showed any effect on the TEER of MCF10A RAB27B KD cells, which were unable to form epithelial polarity (Fig. 4b). These results suggest that it could be the removal of cellular components through apical EVs that facilitates polarization rather than the uptake of EVs from other mammary epithelial cells. We then tested the transwell migration of MCF10A cells in the presence or absence of EVs, and found that basolateral but not apical EVs increased the motility of MCF10A cells (Fig. 4c). Thus, apical and basolateral EVs from polarized MCF10A cells exhibit distinct functions. Further experiments need to be done to understand what molecules are responsible for these specific effects of EVs.

Fig. 4. Different effects of apical and basolateral EVs on cell polarity and migration.

(a) MCF10A cells grown on filters were incubated with CFSE-labelled apical or basolateral MCF10A EVs (green) for 24 h and fixed before fluorescent and phase contrast images were captured. DAPI staining (blue) indicates the nuclei. (b) MCF10A (control or RAB27B KD) cells seeded on transwell filters were treated with apical or basolateral MCF10A EVs isolated from equal number (1:1) or three folds (3:1) of polarized MCF10A cells on day 1 and then on day 3. EVs were added to the upper chambers of transwell inserts. TEER was measured on day 3, 5, and 7. *** P < 0.001 compared to the PBS group. (c) MCF10A cells were mixed with apical or basolateral MCF10A EVs isolated from equal number (1:1) or three folds (3:1) of polarized MCF10A cells, and added to the upper chamber in transwell migration assays. After 24 h, cells that had migrated to the underside of transwell filters were counted. * P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001 compared to the PBS group.

Distinct protein composition of apical and basolateral mammary epithelial EVs

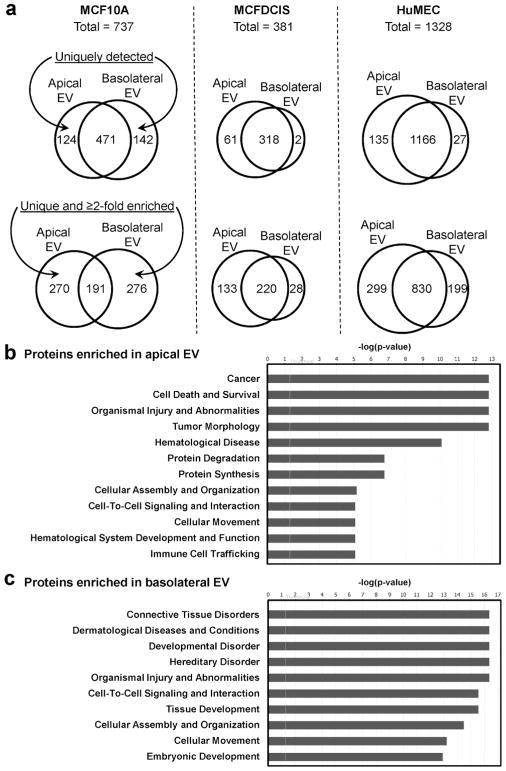

To determine the EV content that may be associated with epithelial polarization and other EV functions, we characterized the protein cargo of EVs isolated from MCF10A cells and primary HuMECs as models of normal epithelia, and from MCFDCIS as a model of disrupted polarity associated with oncogenic transformation. EVs were collected from the apical and basolateral compartments of cells grown in the transwell system described above on day 8 and day 10; collections from the two days were pooled to achieve the yield required for proteomic profiling by mass spectrometry. Among all proteins identified, we focused on those with at least 4 peptide matches. The numbers of proteins exclusively detected from one but not the other compartment, together with or without whose enriched by at least 2 folds in one compartment, are summarized by Venn diagrams for each cell model (Fig. 5a). We further screened for proteins that are unique or enriched by at least 2 folds in either apical or basolateral EVs in both MCF10A cells and HuMECs, as these proteins reflect common differences of polarized EV secretion in both models and may be less related to contextual factors. Following this strategy, we identified 62 proteins enriched in apical EVs, including 29 exclusively detected in the apical but not basolateral EVs of MCF10A (Table 1), as well as 27 proteins enriched in basolateral EVs, including 11 exclusively detected in MCF10A basolateral EVs (Table 2). Many of these proteins associated with polarized EV secretion in normal mammary epithelial cells were not significantly different between the EVs collected from the upper (apical) and lower (basolateral) wells of MCFDCIS cells cultured in the same system (Supplemental Table 1).

Fig. 5. Identification of proteins in apical and basolateral EVs by mass spectrometry.

(a) Venn diagrams showing the numbers of proteins with at least 4 peptide matches in the apical and basolateral EVs from the MCF10A, MCFDCIS (which shows impaired polarity), and HuMEC models. Numbers of proteins that are uniquely detected from one sample (top), or also including whose enriched by at least 2 folds (bottom) are shown. (b, c) EV proteins identified by mass spectrometry with at least 4 peptide matches and enriched by at least 2 folds in apical (b) or basolateral (c) EVs from both MCF10A and HuMEC models were analyzed by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis for the prediction of associated diseases and functions.

Table 1.

Proteins enriched in the apical EVs of MCF10A and primary HuMECs*.

| Symbol | Entrez Gene Name | Location |

|---|---|---|

| ANXA1, ANXA3, ANXA4, ANXA5 | annexin A1, annexin A3, annexin A4, annexin A5 | Plasma Membrane; Cytoplasm |

| AKR1B1 | aldo-keto reductase family 1 member B | Cytoplasm |

| ATP5A1 | ATP synthase, H+ transporting, mitochondrial F1 complex, alpha subunit 1, cardiac muscle | Cytoplasm |

| CKMT1A | creatine kinase, mitochondrial 1A | Cytoplasm |

| CAV1 | caveolin 1 | Plasma Membrane |

| CANX | calnexin | Cytoplasm |

| CCT5 | chaperonin containing TCP1 subunit 5 | Cytoplasm |

| CKAP4 | cytoskeleton associated protein 4 | Cytoplasm |

| EPS8L1, EPS8L2 | EPS8 like 1, EPS8 like 2 | Cytoplasm |

| GRHPR | glyoxylate and hydroxypyruvate reductase | Cytoplasm |

| HIST1H1B, HIST1H2AB, HIST1H2BB, HIST1H4A | histone cluster 1 H1 family member b, histone cluster 1 H2A family member b, histone cluster 1 H2B family member b, histone cluster 1 H4 family member a | Nucleus |

| KTN1 | kinectin 1 | Plasma Membrane |

| LMNA | lamin A/C | Nucleus |

| MVP | major vault protein | Nucleus |

| MYH9 | myosin heavy chain 9 | Cytoplasm |

| NAMPT | nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase | Extracellular Space |

| NCL | nucleolin | Nucleus |

| NPM1 | nucleophosmin | Nucleus |

| PDIA6 | protein disulfide isomerase family A member 6 | Cytoplasm |

| PHB, PHB2 | prohibitin, prohibitin 2 | Nucleus; Cytoplasm |

| PLS3 | plastin 3 | Cytoplasm |

| PPIB | peptidylprolyl isomerase B | Cytoplasm |

| PPL | periplakin | Cytoplasm |

| PSMB1 | proteasome subunit beta 1 | Cytoplasm |

| PTBP1 | polypyrimidine tract binding protein 1 | Nucleus |

| RPL3, RPL4, RPL6, RPL7, RPL7A, RPL8, RPL9, RPL12, RPL13, RPL14, RPL15, RPL17, RPL21, RPL27, RPL28, RPLP2, RPS3A, RPS4X, RPS7, RPS14, RPS18, RPS23 | ribosomal protein L3, L4, L6, L7, L7a, L8, L9, L12, L13, L14, L15, L17, L21, L27, L28, lateral stalk subunit P2, S3A, S4, X-linked, S7, S14, S18, S23 | Cytoplasm; Nucleus |

| RPN1, RPN2 | ribophorin I, II | Cytoplasm |

| RUVBL2 | RuvB like AAA ATPase 2 | Nucleus |

| SPTBN1 | spectrin beta, non-erythrocytic 1 | Plasma Membrane |

| TPM1 | tropomyosin 1 (alpha) | Cytoplasm |

| VDAC1 | voltage dependent anion channel 1 | Cytoplasm |

| ZNF185 | zinc finger protein 185 with LIM domain | Plasma Membrane |

Proteins exclusively detected in the apical but not basolateral EVs of MCF10A are indicated in italics.

Table 2.

Proteins enriched in the basolateral EVs of MCF10A and primary HuMECs*.

| Symbol | Entrez Gene Name | Location |

|---|---|---|

| AHCYL1 | adenosylhomocysteinase like 1 | Cytoplasm |

| CD44 | CD44 molecule (Indian blood group) | Plasma Membrane |

| COL17A1 | collagen type XVII alpha 1 chain | Extracellular Space |

| CTNNB1 | catenin beta 1 | Cytoplasm; Nucleus |

| DLG1 | discs large MAGUK scaffold protein 1 | Plasma Membrane |

| DYNC1I2 | dynein cytoplasmic 1 intermediate chain 2 | Cytoplasm |

| FN1 | fibronectin 1 | Extracellular Space |

| GNAI1 | G protein subunit alpha i1 | Plasma Membrane |

| GNG12 | G protein subunit gamma 12 | Plasma Membrane |

| HLA-A | major histocompatibility complex, class I, A | Plasma Membrane |

| ITGA2, ITGA3, ITGA6, ITGB1, ITGB4 | integrin subunit alpha 2, alpha 3, alpha 6, beta 1, beta 4 | Plasma Membrane |

| LAMA3, LAMB3, LAMC2 | laminin subunit alpha 3, beta 3, gamma 2 | Extracellular Space |

| LCP1 | lymphocyte cytosolic protein 1 | Cytoplasm |

| PLXNB2 | plexin B2 | Plasma Membrane |

| PROM2 | prominin 2 | Plasma Membrane |

| PTGFRN | prostaglandin F2 receptor inhibitor | Plasma Membrane |

| ROCK1 | Rho associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase 1 | Cytoplasm |

| SLC1A5 | solute carrier family 1 member 5 | Plasma Membrane |

| TGFBI | transforming growth factor beta induced | Extracellular Space |

| THBS1 | thrombospondin 1 | Extracellular Space |

| YWHAE | tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5- monooxygenase activation protein epsilon | Cytoplasm |

Proteins exclusively detected in the basolateral but not apical EVs of MCF10A are indicated in italics.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) predicted that the top diseases and functions associated with proteins enriched in apical EVs included cancer, cell death and survival, organismal injury and abnormalities, protein degradation and synthesis, as well as cellular assembly and organization, etc. (Fig. 5b; Supplemental Table 2). In contrast, proteins enriched in basolateral EVs included integrins (α2, α3, α6, β1, and β4) and extracellular matrix proteins (FN1/fibronectin 1; LAMA3/laminin subunit alpha 3; LAMB3/laminin subunit beta 3; LAMC2/laminin subunit gamma 2; and COL17A1/collagen type XVII alpha 1 chain), and were associated with diseases and functions such as connective tissue disorders, developmental disorder, and cell-to-cell signaling and interaction (Fig. 5c; Supplemental Table 2).

Discussion

Virtually all cells in the body secrete EVs, but the potential function of these EVs in epithelial tissues is poorly understood for most tissues. Here we used a transwell system to collect EVs secreted from the apical and basolateral compartments of mammary epithelial cells. Our results are consistent with previously reported findings that used a similar transwell system or immune-affinity to suggest that EVs secreted from the apical versus basolateral sides of the cell contained differences in protein content [16, 17]. Inhibition of EV secretion by knockdown of Rab27a/b inhibited polarization of mammary epithelial cells, suggesting that the secretion of EVs is important for the establishment of polarity. Rab27a/b has been implicated in the regulation of cell polarity through EV-independent mechanisms, including the transport of vesicles to the apical membrane for plasma membrane delivery of proteins such as Podocalyxin and inducing the expression of the tight junction protein Claudin-2 [28, 29]. For many of Rab27’s effects Rab27a and Rab27b are able to at least partially compensate for each other, including the regulation of Claudin-2 expression, however Rab27a and Rab27b have differing roles in the secretion of EVs [30] and as such knocking out either one results in a strong inhibition of EV secretion and polarization. Therefore, we believe that Rab27a/b knockdown inhibits the establishment of polarity primarily through inhibition of EVs. IPA analysis predicted that apical EVs from MCF10A and HuMECs were enriched in proteins associated with metabolic and protein metabolism, e.g., ATP5A1/ATP synthase, H+ transporting, mitochondrial F1 complex, alpha subunit 1, cardiac muscle; CKMT1A/creatine kinase, mitochondrial 1A; AKR1B1/aldo-keto reductase family 1 member B; GRHPR/glyoxylate and hydroxypyruvate reductase; NAMPT/nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase; as well as multiple ribosomal proteins (Table 1; Supplemental Table 2). Our in vitro studies suggest that apical EVs may function through the removal of cellular components rather than addition of effector molecules through EV uptake (Fig. 4b). A similar process has been shown during the maturation of reticulocytes in which exosomes selectively remove many plasma membrane proteins that are absent in mature reticulocytes [31, 32]. Immature reticulocyte-derived exosomes contain transferrin receptors as well as the glucose, nucleoside, and amino acid transporting activities, which are known to diminish or disappear following reticulocyte maturation [33]. Therefore, it is possible that the secretion of apical EVs aids in the establishment of an apical compartment with relatively low metabolic activity and protein synthesis via removing excessive proteins related to these functions. As nutrients would be expected to enter through the basolateral compartment due to its proximity to blood vessels, cellular metabolism and protein synthesis would likely occur closer to the sites of nutrient import. The fate of the excreted apical EVs is unclear but may include their re-uptake by surrounding ductal epithelial cells. The removal, and possibly the re-uptake, of apical EV proteins could allow for their recycling to more synthetically active areas of the tissue.

Apical EVs may also act as a buffering system for mammary epithelial cells. By secreting EVs into the ductal lumen, a shared pool of apical EVs is formed which may help maintain cellular homeostasis. While healthy ductal cells may not need the metabolic constituents of apical EVs, the latter could be important for the survival and recovery of stressed cells. Cellular stresses such as acidity [12] and radiation [34, 35] enhance the uptake of EVs resulting in delivery of proteins that inhibit cell death and promote protein synthesis. Other stresses such as hypoxia may also increase EV uptake as hypoxia results in a downregulation of CAV1 in stromal cells [36, 37], leading to increased EV uptake [38]. This would allow healthy cells to support mildly stressed cells, allowing them to survive and quickly recover to maintain overall ductal integrity. In addition, the enriched presence of annexins (A1, A3, A4, and A5) in apical EVs could suggest a potential role in facilitating the engulfment of apoptotic cells during epithelial polarization and ductal lumen formation.

As the basolateral compartment faces a diverse spectrum of cells including myoepithelial, endothelial, fibroblast, adipocyte, and immune cells, the presence of integrins and signaling molecules (e.g., CTNNB1/catenin beta 1; GNAI1/G protein subunit alpha i1; GNG12/G protein subunit gamma 12; and ROCK1/Rho associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase 1) may mediate the cellular tropism and potential intracellular effects of basolateral EVs upon their transfer to other cells. Since integrins have been shown to determine the organotropism of exosomes [39], this may indicate that basolateral EVs may act over a longer distance than apical EVs and display a more specific cellular tropism. Interestingly ITGB4 and ITGA6 were the most enriched proteins in MCF10A basolateral EVs. These integrins bind to laminin, one of the most abundant extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules in the breast microenvironment, which can anchor the EVs to the ECM to give cells time for interaction with the EVs [39].

Addition of basolateral EVs had no apparent effect on polarization, however it cannot be ruled out that this is due to a limitation in our system as basolateral EVs would likely only be taken up through the basolateral compartment in mammary epithelial cells. Instead, we show that basolateral but not apical EVs can promote cell migration (Fig. 4c). EVs secreted by migrating cells have been shown to promote directional migration through ECM molecules such as fibronectin [40]. We found that basolateral mammary epithelial EVs contain fibronectin, which could be involved in their effect on promoting migration. In a healthy mammary duct the epithelial cells are surrounded by supportive stromal cells, which may take up basolateral epithelial EVs. Disruption of the stromal layer would result in EVs leaking out into the surrounding microenvironment where they can bind to the laminin-rich ECM through integrins such as ITGB4 and ITGA6, generating a trail of EVs which can guide the migration of stromal cells to the epithelium. Once the mammary epithelial cells are surrounded by supportive stromal cells, they may continue to secrete these EVs to protect against potential insults. Thus, there is a possibility that EVs secreted from mammary epithelial cells contribute to the maintenance of ductal homeostasis by rapidly inducing repairs within the duct through apical EVs and outside the duct through basolateral EVs. Future experiments are needed to examine these speculations.

Materials and Methods

Cells and reagents

The non-cancerous human mammary epithelial cell line MCF10A was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA) and cultured as reported [41, 42]. MCF- 10DCIS.com (MCFDCIS) cells were purchased from Asterand (Detroit, MI) and cultured in MCF10A media. HuMECs were purchased from ATCC and cultured in HuMEC Ready Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA). For EV collection, MCF10A and MCFDCIS cells were grown in media containing EV-depleted horse serum generated by spinning medium-diluted horse serum at 110,000 × g for 16 hr and discarding the EV pellet. The following antibodies were used for Western blot: CD9 (catalog # 13403; Cell Signaling Technology; Danvers, MA), CD63 (catalog # sc-59286; Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Santa Cruz, CA), TSG101 (catalog # MA1-23296; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and GM130 (catalog # 12480; Cell Signaling Technology). Rab27a/b knockdown cell lines were generated by clonal selection of cells transduced with lentivirus carrying MISSION pLKO.1-puro-RAB27A or -RAB27B shRNA (RAB27A: catalog # SHCLNG-NM_004580, TRC # TRCN0000380306; RAB27B: catalog # SHCLND-NM_004163, TRC # TRCN0000294016) or pLKO.1-puro empty vector control (catalog # SHC001) from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

EV isolation

Apical and basolateral media was spun down at 500 × g for 5 min in a tabletop centrifuge at 4 °C to remove any cellular contaminants. The supernatant was spun at 18,700 × g for 20 min in a Sorvall Lynx 6000 (Fisher Scientific) centrifuge to remove cellular debris. EVs were pelleted by spinning the supernatant at 110,000 × g for 70 min at 4 °C in a LE-80 ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter; Indianapolis, IN). The EV-depleted supernatant was removed and the EV pellet was washed with PBS and spun again at 110,000 × g for 70 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was removed by aspiration and the pellet was resuspended in a small volume of PBS. When indicated, CFSE (carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added into the PBS at 5 μM and incubated for 20 min before the washing spin, followed by an additional wash to remove the excess dye. For gradient separation we used a protocol modified from [43–45]. EVs isolated by ultracentrifugation were loaded onto a 12-step iodixanol (OptiPrep; Sigma-Aldrich) gradient consisted of 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 12.5, 15, 17.5, 20, 22.5, 25, 27.5, and 30% iodixanol fractions (from top to bottom) in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.2), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na3VO4, and 50 mM NaF. After centrifugation in a SW 40 Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter) at 110,000 × g at 4°C for 16 hr, 12 1-ml fractions were collected. Each fraction was individually diluted in PBS, and EVs were pelleted by spinning at 110,000 × g for 70 min in a LE-80 ultracentrifuge. EV pellets were resuspended in protein lysis buffer for Western blot analysis.

Transwell insert culture

For transwell insert culture, 8 × 106 cells were seeded into 10-cm polycarbonate membrane transwells (Corning; Corning, NY) and were grown for 8 days before further experiments unless otherwise specified. Media was changed every other day. Apical media was collected from the transwell insert, while basolateral media was collected from the lower chamber (Fig. 1a). TEER was assessed using an EVOM2 Epithelial Volt/Ohm (TEER) Meter (World Precision Instruments; Sarasota, FL) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Diffusion of phenol red was performed as described [46]. In brief, phenol red-containing media was added to the transwell insert and phenol red-free media to the lower chamber, so that phenol red was allowed to diffuse in the cell culture incubator. After 1 hr, media was collected from the lower chamber, titrated to pH 11, and incubated at room temperature for 1 hr. The intensity of phenol red was measured by assessing the absorbance at 558 nm.

Immunofluorescence assay

Immunofluorescence was performed as described [47] using antibodies against Podocalyxin (catalog # PA1-46169; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Syntaxin-4 (catalog # 610439; BD Biosciences; San Jose, CA). Confocal analyses were performed using an Olympus FV3000 confocal microscopy system (Olympus; Waltham, MA).

Transwell migration assay

Migration assays were performed utilizing 5 μm pore, 6.5 mm polycarbonate transwell filters (Corning). Cells (1.5 × 105 per well) were mixed with EVs as indicated and seeded in serum-free medium onto the upper surface of the filters and allowed to migrate. After 24 hr, the cells on the upper surface of the filters were wiped off with a cotton swab. Cells that had migrated to the filter underside were fixed, stained with crystal violet, and counted by bright field microscopy.

Mass spectrometry proteomic analysis

EVs were diluted in pre-chilled HPLC-MS grade water to reach a volume of 400 μl. Then, 100 μl of freshly prepared 100% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was added to each sample. Samples were vortexed and incubated on ice for 15 min before centrifugation for 15 min at top speed (16,000 × g) in a microfuge at 4 °C. Pellets were washed in 1 ml of 10% TCA, and then washed twice in 1 ml of cold acetone. Pellets were then dried by speed-vac for 10 min, before submission to the Taplin Biological Mass Spectrometry Facility (Boston, MA) for enzyme digestion and microcapillary liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry peptide sequencing using an Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for protein identification.

Statistical analysis

All results were confirmed in at least three independent experiments, and data from one representative experiment are shown. All quantitative data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.) unless otherwise specified. One-way or two-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey tests were used for comparison between independent groups. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Cancer Institute (NCI) grants R01CA166020 (SEW), R01CA218140 (SEW), and R01CA206911 (SEW). Research reported in this publication included work performed in core facilities supported by the NIH/NCI under grant number P30CA23100 (UCSD Cancer Center) and P30CA33572 (City of Hope Cancer Center).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

A.R.C. and S.E.W. conceived ideas and contributed to project planning. A.R.C. and S.E.W. designed and performed most of the experiments. W.Y., M.C., and X.L. assisted with EV characterization and Western analyses. A.R.C. and S.E.W. wrote the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Chin AR, Wang SE. Cancer Tills the Premetastatic Field: Mechanistic Basis and Clinical Implications. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(15):3725–33. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chin AR, Wang SE. Cancer-derived extracellular vesicles: the ‘soil conditioner’ in breast cancer metastasis? Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2016;35(4):669–76. doi: 10.1007/s10555-016-9639-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deatherage BL, Cookson BT. Membrane vesicle release in bacteria, eukaryotes, and archaea: a conserved yet underappreciated aspect of microbial life. Infect Immun. 2012;80(6):1948–57. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06014-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Vizio D, Kim J, Hager MH, Morello M, Yang W, Lafargue CJ, et al. Oncosome formation in prostate cancer: association with a region of frequent chromosomal deletion in metastatic disease. Cancer Res. 2009;69(13):5601–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salomon C, Ryan J, Sobrevia L, Kobayashi M, Ashman K, Mitchell M, et al. Exosomal signaling during hypoxia mediates microvascular endothelial cell migration and vasculogenesis. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e68451. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kucharzewska P, Christianson HC, Welch JE, Svensson KJ, Fredlund E, Ringnér M, et al. Exosomes reflect the hypoxic status of glioma cells and mediate hypoxia-dependent activation of vascular cells during tumor development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(18):7312–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220998110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King HW, Michael MZ, Gleadle JM. Hypoxic enhancement of exosome release by breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park JE, Tan HS, Datta A, Lai RC, Zhang H, Meng W, et al. Hypoxic tumor cell modulates its microenvironment to enhance angiogenic and metastatic potential by secretion of proteins and exosomes. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9(6):1085–99. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900381-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramteke A, Ting H, Agarwal C, Mateen S, Somasagara R, Hussain A, et al. Exosomes secreted under hypoxia enhance invasiveness and stemness of prostate cancer cells by targeting adherens junction molecules. Mol Carcinog. 2015;54(7):554–65. doi: 10.1002/mc.22124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray WD, French KM, Ghosh-Choudhary S, Maxwell JT, Brown ME, Platt MO, et al. Identification of therapeutic covariant microRNA clusters in hypoxia-treated cardiac progenitor cell exosomes using systems biology. Circ Res. 2015;116(2):255–63. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.304360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salomon C, Kobayashi M, Ashman K, Sobrevia L, Mitchell MD, Rice GE. Hypoxia-induced changes in the bioactivity of cytotrophoblast-derived exosomes. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e79636. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parolini I, Federici C, Raggi C, Lugini L, Palleschi S, De Milito A, et al. Microenvironmental pH is a key factor for exosome traffic in tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(49):34211–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.041152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahashi A, Okada R, Nagao K, Kawamata Y, Hanyu A, Yoshimoto S, et al. Exosomes maintain cellular homeostasis by excreting harmful DNA from cells. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15287. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lehmann BD, Paine MS, Brooks AM, McCubrey JA, Renegar RH, Wang R, et al. Senescence-associated exosome release from human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68(19):7864–71. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Effenberger T, von der Heyde J, Bartsch K, Garbers C, Schulze-Osthoff K, Chalaris A, et al. Senescence-associated release of transmembrane proteins involves proteolytic processing by ADAM17 and microvesicle shedding. FASEB J. 2014;28(11):4847–56. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-254565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tauro BJ, Greening DW, Mathias RA, Mathivanan S, Ji H, Simpson RJ. Two distinct populations of exosomes are released from LIM1863 colon carcinoma cell-derived organoids. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12(3):587–98. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.021303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Niel G, Raposo G, Candalh C, Boussac M, Hershberg R, Cerf-Bensussan N, et al. Intestinal epithelial cells secrete exosome-like vesicles. Gastroenterology. 2001;121(2):337–49. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.26263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lötvall J, Hill AF, Hochberg F, Buzás EI, Di Vizio D, Gardiner C, et al. Minimal experimental requirements for definition of extracellular vesicles and their functions: a position statement from the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 2014;3:26913. doi: 10.3402/jev.v3.26913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Q, Takada R, Noda C, Kobayashi S, Takada S. Different populations of Wnt-containing vesicles are individually released from polarized epithelial cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35562. doi: 10.1038/srep35562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang L, Shen Y, Guo D, Yang D, Liu J, Fei X, et al. EpCAM-dependent extracellular vesicles from intestinal epithelial cells maintain intestinal tract immune balance. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13045. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klingeborn M, Dismuke WM, Skiba NP, Kelly U, Stamer WD, Bowes Rickman C. Directional Exosome Proteomes Reflect Polarity-Specific Functions in Retinal Pigmented Epithelium Monolayers. Scientific reports. 2017;7(1):4901. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05102-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moberg KH, Schelble S, Burdick SK, Hariharan IK. Mutations in erupted, the Drosophila ortholog of mammalian tumor susceptibility gene 101, elicit non-cell-autonomous overgrowth. Dev Cell. 2005;9(5):699–710. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sreekumar PG, Kannan R, Kitamura M, Spee C, Barron E, Ryan SJ, et al. αB crystallin is apically secreted within exosomes by polarized human retinal pigment epithelium and provides neuroprotection to adjacent cells. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e12578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang YT, Huang YY, Zheng L, Qin SH, Xu XP, An TX, et al. Comparison of isolation methods of exosomes and exosomal RNA from cell culture medium and serum. Int J Mol Med. 2017;40(3):834–44. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szatanek R, Baran J, Siedlar M, Baj-Krzyworzeka M. Isolation of extracellular vesicles: Determining the correct approach (Review) Int J Mol Med. 2015;36(1):11–7. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu M, Yao J, Carroll DK, Weremowicz S, Chen H, Carrasco D, et al. Regulation of in situ to invasive breast carcinoma transition. Cancer Cell. 2008;13(5):394–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.03.007. S1535-6108(08)00091-3 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller FR, Santner SJ, Tait L, Dawson PJ. MCF10DCIS.com xenograft model of human comedo ductal carcinoma in situ. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(14):1185–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.14.1185a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yasuda T, Saegusa C, Kamakura S, Sumimoto H, Fukuda M. Rab27 effector Slp2-a transports the apical signaling molecule podocalyxin to the apical surface of MDCK II cells and regulates claudin-2 expression. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23(16):3229–39. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-02-0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galvez-Santisteban M, Rodriguez-Fraticelli AE, Bryant DM, Vergarajauregui S, Yasuda T, Banon-Rodriguez I, et al. Synaptotagmin-like proteins control the formation of a single apical membrane domain in epithelial cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(8):838–49. doi: 10.1038/ncb2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ostrowski M, Carmo NB, Krumeich S, Fanget I, Raposo G, Savina A, et al. Rab27a and Rab27b control different steps of the exosome secretion pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(1):19–30. doi: 10.1038/ncb2000. sup pp 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harding C, Heuser J, Stahl P. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of transferrin and recycling of the transferrin receptor in rat reticulocytes. J Cell Biol. 1983;97(2):329–39. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.2.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pan BT, Johnstone RM. Fate of the transferrin receptor during maturation of sheep reticulocytes in vitro: selective externalization of the receptor. Cell. 1983;33(3):967–78. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnstone RM, Adam M, Hammond JR, Orr L, Turbide C. Vesicle formation during reticulocyte maturation. Association of plasma membrane activities with released vesicles (exosomes) J Biol Chem. 1987;262(19):9412–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hazawa M, Tomiyama K, Saotome-Nakamura A, Obara C, Yasuda T, Gotoh T, et al. Radiation increases the cellular uptake of exosomes through CD29/CD81 complex formation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;446(4):1165–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mutschelknaus L, Peters C, Winkler K, Yentrapalli R, Heider T, Atkinson MJ, et al. Exosomes Derived from Squamous Head and Neck Cancer Promote Cell Survival after Ionizing Radiation. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0152213. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Trimmer C, Lin Z, Whitaker-Menezes D, Chiavarina B, Zhou J, et al. Autophagy in cancer associated fibroblasts promotes tumor cell survival: Role of hypoxia, HIF1 induction and NFκB activation in the tumor stromal microenvironment. Cell Cycle. 2010;9(17):3515–33. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.17.12928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pavlides S, Tsirigos A, Vera I, Flomenberg N, Frank PG, Casimiro MC, et al. Loss of stromal caveolin-1 leads to oxidative stress, mimics hypoxia and drives inflammation in the tumor microenvironment, conferring the "reverse Warburg effect": a transcriptional informatics analysis with validation. Cell Cycle. 2010;9(11):2201–19. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.11.11848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Svensson KJ, Christianson HC, Wittrup A, Bourseau-Guilmain E, Lindqvist E, Svensson LM, et al. Exosome uptake depends on ERK1/2-heat shock protein 27 signaling and lipid Raft-mediated endocytosis negatively regulated by caveolin-1. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(24):17713–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.445403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoshino A, Costa-Silva B, Shen TL, Rodrigues G, Hashimoto A, Tesic Mark M, et al. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature. 2015;527(7578):329–35. doi: 10.1038/nature15756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sung BH, Ketova T, Hoshino D, Zijlstra A, Weaver AM. Directional cell movement through tissues is controlled by exosome secretion. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7164. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Debnath J, Mills KR, Collins NL, Reginato MJ, Muthuswamy SK, Brugge JS. The role of apoptosis in creating and maintaining luminal space within normal and oncogene-expressing mammary acini. Cell. 2002;111(1):29–40. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou W, Fong MY, Min Y, Somlo G, Liu L, Palomares MR, et al. Cancer-Secreted miR-105 Destroys Vascular Endothelial Barriers to Promote Metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(4):501–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.03.007. S1535-6108(14)00116-0 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tauro BJ, Greening DW, Mathias RA, Ji H, Mathivanan S, Scott AM, et al. Comparison of ultracentrifugation, density gradient separation, and immunoaffinity capture methods for isolating human colon cancer cell line LIM1863-derived exosomes. Methods. 2012;56(2):293–304. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kowal J, Arras G, Colombo M, Jouve M, Morath JP, Primdal-Bengtson B, et al. Proteomic comparison defines novel markers to characterize heterogeneous populations of extracellular vesicle subtypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(8):E968–77. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521230113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li X, Galli T, Leu S, Wade JB, Weinman EJ, Leung G, et al. Na+-H+ exchanger 3 (NHE3) is present in lipid rafts in the rabbit ileal brush border: a role for rafts in trafficking and rapid stimulation of NHE3. J Physiol. 2001;537(Pt 2):537–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00537.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Briske-Anderson MJ, Finley JW, Newman SM. The influence of culture time and passage number on the morphological and physiological development of Caco-2 cells. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1997;214(3):248–57. doi: 10.3181/00379727-214-44093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gillespie JL, Anyah A, Taylor JM, Marlin JW, Taylor TA. A Versatile Method for Immunofluorescent Staining of Cells Cultured on Permeable Membrane Inserts. Med Sci Monit Basic Res. 2016;22:91–4. doi: 10.12659/MSMBR.900656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.