Abstract

The chemokine CCL28 is constitutively expressed in mucosal tissues and is abundant in low-salt mucosal secretions. Beyond its traditional role as a chemoattractant, CCL28 has been shown to act as a potent and broad-spectrum antimicrobial agent with particular efficacy against the commensal fungus and opportunistic pathogen Candida albicans. However, the structural features that allow CCL28 to perform its chemotactic and antimicrobial functions remain unknown. Here, we report the structure of CCL28, solved using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. CCL28 adopts the canonical chemokine tertiary fold, but also has a disordered C-terminal domain that is partially tethered to the core by a non-conserved disulfide bond. Structure-function analysis reveals that removal of the C-terminal tail reduces the antifungal activity of CCL28 without disrupting its structural integrity. Conversely, removal of the nonconserved disulfide bond destabilizes the tertiary fold of CCL28 without altering its antifungal effects. Moreover, we report that CCL28 unfolds in response to low pH but is stabilized by the presence of salt. To explore the physiologic relevance of the observed structural lability of CCL28, we investigated the effects of pH and salt on the antifungal activity of CCL28 in vitro. We found that low pH enhances the antifungal potency of CCL28, but also that this pH effect is independent of CCL28’s tertiary fold. Given its dual role as a chemoattractant and antimicrobial agent, our results suggest that changes in the salt concentration or pH at mucosal sites may fine-tune CCL28’s functional repertoire by adjusting the thermostability of its structure.

Keywords: NMR, Candida, pH, Salt, Chemokine

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION

Chemokines (i.e., chemotactic cytokines) are a family of ~50 small, secreted proteins that act to orchestrate leukocyte migration through their interactions with G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) [1]. However, it is becoming increasingly recognized that chemokines have roles beyond the coordination of cellular chemotaxis, and a number of chemokines have now been identified as antimicrobial proteins [2]. Antimicrobial proteins and peptides (AMPs) are small, cationic, and frequently amphipathic peptides that directly kill bacterial pathogens by interacting with and/or translocating across the negatively-charged bacterial membranes [3–5]. As nearly all chemokines are positively-charged at physiologic pH (i.e., chemokine pI values range from 8–12), a charge interaction is similarly thought to be an important factor for their antibacterial mechanism of action [2]. Importantly, several chemokines (e.g., CCL20, CXCL14, and CCL28) and other traditional AMPs (e.g., LL-37, Histatin 5, and β-defensins) possess the ability to directly kill fungal pathogens [6–11]. Though the antifungal mechanism of action for chemokines is less well understood, their antifungal activity is similar to that of the traditional antifungal AMPs (i.e., IC50 values in the low μM range) [5,11,12].

CCL28, also known as mucosae-associated epithelial chemokine (MEC), is a chemokine constitutively expressed in a number of mucosal tissues and is well-established as an important mediator of mucosal immunity [13]. CCL28 elicits cellular chemotaxis through interactions with two G protein-coupled receptors: CCR10, expressed primarily on lymphocytes, and CCR3, expressed primarily on eosinophils [14,15]. In addition to its chemotactic capabilities, CCL28 has been identified as a potent and broad-spectrum antimicrobial protein with activity against bacteria, fungi, and protozoa [11,16,17]. Like other antimicrobial proteins, the antimicrobial activity of CCL28 has been shown to be highly salt-dependent, with even physiologic concentrations of salt (i.e., >50 mM NaCl) significantly disrupting antimicrobial efficacy in vitro [2,3,11]. Consistent with these findings, CCL28 is secreted at high levels in human saliva (i.e., 30–230 nM) and milk (i.e., 13–34 nM) [11], where salt concentrations are relatively low (i.e., 2–50 mM and 5–8 mM, respectively) [2], suggesting that CCL28 may act as an antimicrobial protein at these sites in vivo. Moreover, CCL28 is particularly effective against the fungal species Candida albicans, the commensal microbe and opportunistic pathogen abundant in the mouth and gastrointestinal tract, sites where CCL28 is abundantly expressed [11,14,18]. Previously, Hieshima and colleagues demonstrated that C-terminal domain of CCL28 (i.e., the last 28 amino acid residues) has considerable sequence homology to the salivary antifungal peptide histatin-5 (i.e., 32% sequence identity, 53% sequence similarity), and that a peptide consisting solely of CCL28’s C-terminal domain retains much of the in vitro candidacidal activity observed for the full-length protein (i.e., only a 2-fold change in IC50 value) [11].

Decades of structural studies have confirmed that chemokines share a common tertiary fold consisting of an unstructured N-terminal domain, 1–2 disulfide bonds, a three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet, and a C-terminal α-helix [19]. Though most chemokines have only 1–2 disulfide bonds, five human chemokines in the CC subfamily (i.e., CCL1, CCL15, CCL21, CCL23, and CCL28) have two additional cysteine residues capable of forming a unique third disulfide bond (termed 6C chemokines). The NMR solution structures of CCL1 [20], CCL15 [21], CCL21 [22], and CCL23 [23] have shown that the structural consequences of an additional disulfide bond for chemokines can vary. For example, the additional disulfide bond present in CCL21 exists within its unstructured C-terminal domain [22], and the additional disulfide bond present in CCL15 and CCL23 links the short helical region that precedes the first β-strand to the C-terminal α-helix [21,23]. The additional disulfide present in CCL1 links the first β-strand and the unstructured C-terminal tail, creating a unique structural region not seen in other chemokines [20]. Though Sticht and colleagues demonstrated that mutagenic disruption of the additional disulfide bond present in CCL15 minimally perturbs the structure, functional consequences were not investigated [21]. Overall, the structural or functional significance of the additional disulfide bonds in 6C chemokines remains largely uninvestigated.

In this study, we investigate the unique structural features of CCL28 and their role in antimicrobial efficacy against Candida albicans. We present the solution structure of CCL28, solved by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR). The structure reveals that CCL28 adopts the canonical chemokine tertiary fold, but has distinctive structural features including an additional disulfide bond linking its first β-strand to its unstructured C-terminal tail. We find that CCL28 undergoes a pH-dependent fold transition near pH 5, a phenomenon that can be stabilized by the addition of 150mM NaCl. We show that mutagenic disruption of the additional disulfide bond significantly destabilizes the tertiary fold of CCL28, while removal of the C-terminal tail minimally alters the CCL28 stability. In vitro Candida killing assays with purified human recombinant CCL28 protein revealed that while the fold of CCL28 is necessary for in vitro chemotaxis [24], it is not necessary for direct fungal killing. Additionally, while disruption of the additional disulfide bond has a minimal effect on both in vitro GPCR activation and in vitro fungal killing, removal of the 28-amino acid C-terminal domain of CCL28 significantly reduces antifungal potency without altering CCL28’s capacity for GPCR activation. Finally, we observed a pH-dependence to the fungicidal activity of CCL28, with low pH enhancing CCL28’s antifungal activity. Collectively, these findings support a model in which the structural lability of CCL28 may be important for its dual functions in vivo.

RESULTS

The NMR Solution Structure of CCL28 Reveals Unique Structural Features

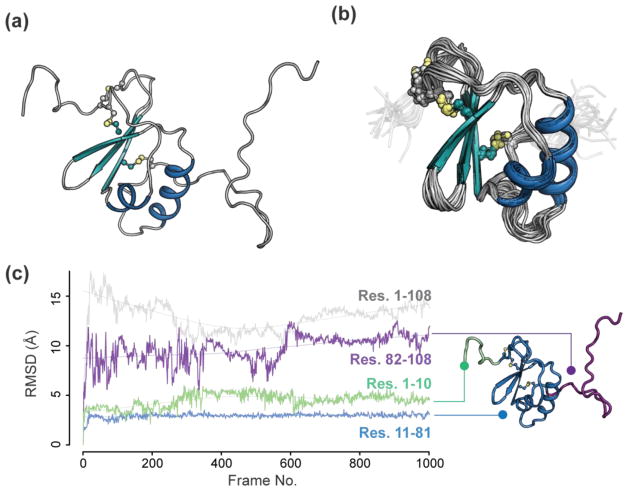

In a previous study, we used mass spectrometry and NMR to demonstrate that CCL28 has a third disulfide bond [24]. In order to understand the role of the third disulfide bond on CCL28 structure, we solved the NMR solution structure of CCL28 and observed structural features distinguishing CCL28 from other chemokines (Fig. 1, Table 1). At its core, CCL28 adopts the canonical chemokine tertiary fold of a three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet and α-helix (Fig. 1A), and the NMR structural ensemble shows good agreement in this region (i.e., average pairwise Cα RMSD of residues 11–81 = 0.84; Fig. 1B). In addition to the two canonical disulfide bonds present near the N-terminus of the protein, our structure verified that CCL28 has an additional disulfide bond linking a portion of the C-terminal tail to the first β-strand of the chemokine core (Fig. 1A–B). This additional disulfide bond facilitates the formation of an ordered loop between the end of the α-helix and the disulfide bond. Following the additional disulfide bond is a 28 residue C-terminal tail which is largely unstructured following His 85, in agreement with our previous 1H, 15N heteronuclear NOE analysis [24].

Figure 1. NMR Solution Structure of CCL28.

(a) Cartoon representation of full-length CCL28, disulfide bonds are show as yellow spheres. (b) Ensemble of the top 20 NMR structures. Residues shown represent those used to calculate structural statistics (residue numbers 11–81), with N-terminal residues 8–10 and C-terminal 82–86 shown in transparent. (c) A 500 ns, 1000 frame MD simulation of the NMR structure of CCL28 with Cα root mean square deviation (RMSD) plotted by frame number for different portions of the protein (residue numbers indicated in figure).

Table 1.

Statistics for the 20 CCL28 Conformers

| Experimental constraints | |||

|

| |||

| Distance constraints for each monomer | |||

| Residues | 1–108 | 11–81 | |

| Long | 390 | 385 | |

| Medium [1<(i−j)≤5] | 278 | 274 | |

| Sequential [ (i−j) = 1] | 345 | 318 | |

| Intraresidue [i=j] | 369 | 313 | |

| Total | 1382 | 1290 | |

| Dihedral angle constraints (ϕ and ψ) | 105 | 103 | |

| Number of restrains per residue | 13.7 | 19.6 | |

| Number of long-range restrains per residue | 3.6 | 5.4 | |

|

| |||

| Average atomic R.M.S.D. to the mean structure (Å) | |||

| Residues | 11–81 | ||

| Backbone (Cα , C′, N) | 0.56 ± 0.11 | ||

| Heavy atoms | 1.09 ± 0.13 | ||

|

| |||

| Deviations from idealized covalent geometry | |||

| Bond lengths | RMSD (Å) | 0.012 | |

| Torsion angle violations | RMSD (°) | 1.3 | |

|

| |||

| Constraint violations | |||

| NOE distance | Number > 0.5 Åa | 0 ± 0 | |

| NOE distance | RMSD (Å) | 0.019 ± 0.001 | |

| Torsion-angle violations | Number > 5 °b | 0.0 ± 0 | |

| Torsion-angle violations | RMSD (°) | 0.618 ± 0.091 | |

|

| |||

| Global quality scores (raw/Z score)c | |||

| Verify3D | 0.28/–2.89 | ||

| Prosall | 0.47/-0.74 | ||

| PROCHECK (ϕ–ψ)d | -0.51/-1.69 | ||

| PROCHECK (all)d | -0.44/-2.60 | ||

| MolProbity clash score | 20.29/-1.96 | ||

|

| |||

| Ramachandran statistics (% of all residues)e | |||

| Most favored | 87.5 | ||

| Additionally allowed | 9.1 | ||

| Generously allowed | 1.6 | ||

| Disallowed | 1.8 | ||

The largest NOE violation in the ensemble of structures was 0.25 Å.

The largest torsion-angle violation in the ensemble of structures was 4.3°.

Calculated using PSVS version 1.5

Based on ordered residues 11–81 and.

Ramachandran statistics calculated using PROCHECK for residues 11–81.

To further investigate the dynamics of the unique C-terminal domain, we performed a 0.5 microsecond molecular dynamics simulation of CCL28 in the presence of explicit solvent (Fig. 1C). In agreement with the NMR structural ensemble, the core chemokine domain of CCL28 is stable over the course of the simulation, with a mean Cα RMSD value for residues 11–81 of approximately 2.9 Å. Additionally, the N- and C-terminal domains are dynamic throughout the simulation, with the C-terminal tail experiencing more dramatic fluctuations than the N-terminal domain (i.e., the mean the Cα RMSD for tail residues ~ 9.6 Å, the mean the Cα RMSD for N-terminal residues ~ 4.5 Å). Notably, the third disulfide stabilizes the C-terminus beyond the αhelix up through Cys 80 (i.e., residues 70–80), creating a relatively structured loop with a mean Cα RMSD of ~ 2.8 Å over the course of the simulation.

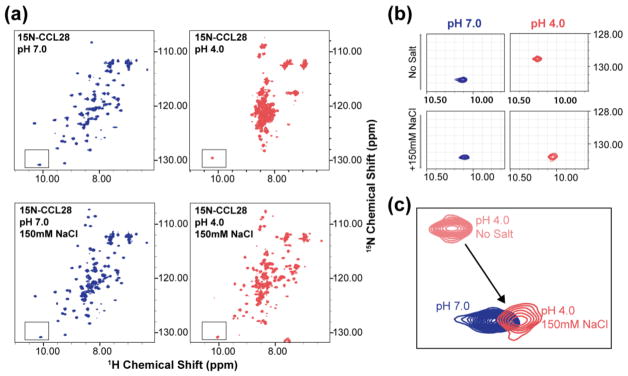

The Tertiary Fold of CCL28 is Sensitive to pH and Salt

In our efforts to experimentally determine the NMR solution structure of CCL28, we were surprised to find that the tertiary fold of CCL28 is sensitive to changes in pH and salt (Fig. 2). At pH 7, the 1H, 15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectrum of 15N-CCL28 demonstrates peaks of uniform intensity and with favorable chemical shift dispersion in both the 1H and 15N dimension, features indicative of a well-folded protein (Fig. 2A, Top Left). However, when the pH is reduced to 4, the chemical shift dispersion in the 1H dimension collapses, and spectral crowding predominates near 8.5 ppm, findings consistent with an unfolded protein (Fig. 2A, Top Right). In the presence of 150 mM NaCl, the transition to pH 4 also induces a change in the HSQC spectrum (Fig. 2A, Bottom), but significant chemical shift dispersion persists at the lower pH. Inspection of the indole nitrogen (NεH) peak of tryptophan 65 (W65) reveals that a pH-dependent shift in the 1H and 15N dimensions is largely suppressed when 150 mM NaCl is added to the sample (Fig. 2B–C). By inspecting both the 1H chemical shift of the W65 NεH peak (Fig. 3A, Bottom) and the relative chemical shift dispersion in the 1H dimension (Fig. 3A–B) as the pH of the sample was titrated from pH 7 to pH 4, we found that the fold transition occurs between pH 5.5 and pH 4.5.

Figure 2. The tertiary fold of CCL28 is destabilized at near-physiologic pH and can be stabilized by physiologic concentrations of salt.

(a) 1H, 15N HSQC spectra of full-length CCL28 at pH 7 (blue) and pH 4 (red) without salt (top) and in the presence of 150 mM NaCl (bottom). (b) Highlighting the W65 NεH peak position. (c) Overlay of the W65 NεH peak position at different pH and salt conditions.

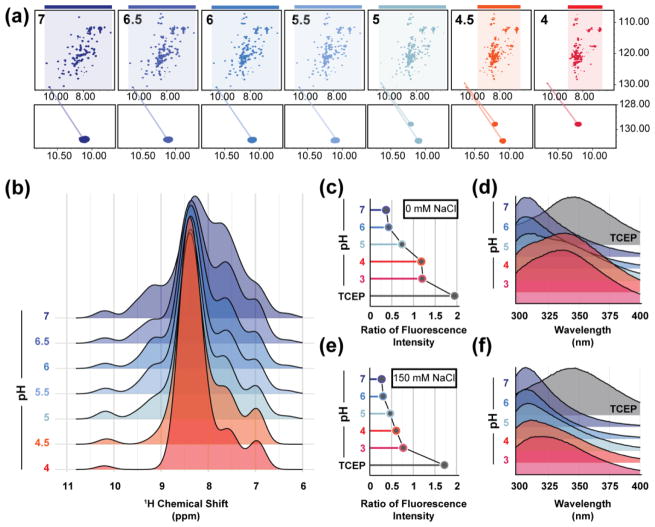

Figure 3. CCL28 unfolds in response to low pH and can be stabilized by physiologic concentrations of salt.

(a) A pH titration monitored by 1H, 15N HSQC highlighting the structural change that occurs between pH 5.5 and 4.5. Bottom panels highlight the NεH peak position. (b) A histogram showing the relative 1H chemical shift distribution. (c) The ratio of fluorescence intensity at the unfolded (348 nm) and folded (308 nm) λmax for WT-CCL28 in the absence of salt (0 mM NaCl) at pH 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, and pH 7 with the addition of TCEP (disulfide reducing agent, dark grey). (d) Intrinsic tryptophan emission spectra for WT-CCL28 in the absence of salt (e) The ratio of fluorescence intensity at the unfolded (348 nm) and folded (308 nm) λmax for WT-CCL28 in the presence of salt (150 mM NaCl) at pH 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, and pH 7 with the addition of TCEP (disulfide reducing agent, dark grey). (f) Intrinsic tryptophan emission spectra for WT-CCL28 in the presence of salt.

Finally, to investigate the pH-dependent structural lability of CCL28 using a complementary method, an analogous pH titration was performed but instead monitored by intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence (Fig. 3C–F). By comparing the emission spectra of CCL28 before and after reduction of all three disulfide bonds, we discovered that the intrinsic fluorescence of W65 is strongly quenched in the folded state (Fig. 3D, 3F). Therefore, the λmax of the emission spectrum of folded CCL28 corresponds to the intrinsic fluorescence of tyrosine residues in the C-terminal domain of CCL28 (λmax = 308 nm). However, sequential reduction in pH leads to an increase in fluorescence emission intensity at 348 nm, the λmax of a solvent-exposed tryptophan residue. The fluorescence emission spectrum of CCL28 experiences a red shift in the λmax from 308 nm to 348 nm between pH 6 and pH 4, in agreement with the NMR results (Fig. 3C–F). Moreover, addition of 150 mM NaCl protects against the pH-dependent structural lability, and even at pH 3 the ratio of fluorescence emission intensity of the unfolded (348 nm) to folded (308 nm) wavelengths is < 1 (Fig. 3E).

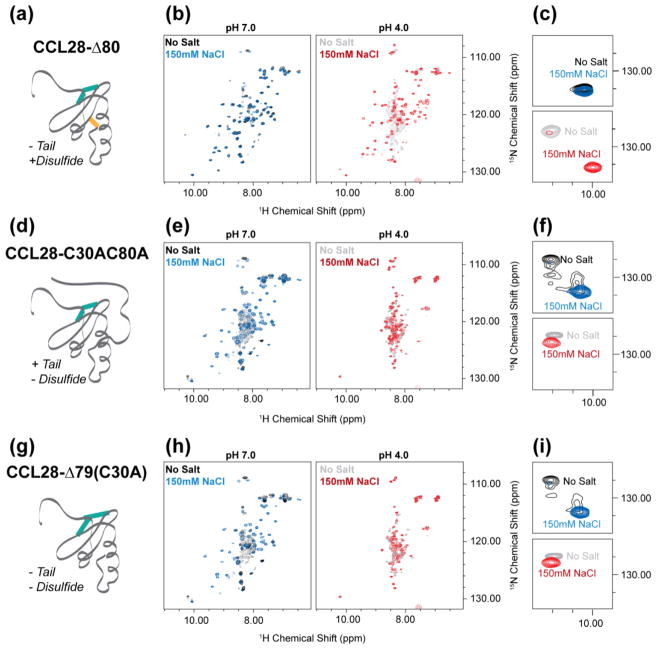

Removal of the Additional Disulfide Bond Significantly Destabilizes the Tertiary Fold of CCL28

To investigate the role of the unique C-terminal domain in CCL28’s pH-dependent structural lability, three CCL28 variants were generated: CCL28-Δ80 (i.e., C-terminally truncated with an intact additional disulfide bond), CCL28-C30AC80A (i.e., full length CCL28 without the additional disulfide bond), and CCL28-Δ79 (C30A) (i.e., C-terminally truncated without the additional disulfide bond) (diagrammed in Fig. 4). Interestingly, we observed a WT-like pattern of pH-dependent structural changes with the C-terminally truncated variant (CCL28-Δ80; Fig. 4B–C), indicating the extended C-terminal domain likely does not play a role in this phenomenon. In contrast, loss of the additional disulfide bond significantly alters the pattern of pH-dependent structural changes. At pH 7, the HSQC spectrum of 15N-CCL28-C30AC80A contains broad peaks of non-uniform intensity (Fig. 4E, Left) and inspection of the W65 NεH peak reveals apparent exchange (Fig. 4F, Top), features indicative of an unstable tertiary fold. However, addition of 150 mM NaCl increases chemical shift dispersion in the 1H dimension and collapses the W65 NεH peak to the folded position indicating a salt-dependent stabilization of the tertiary fold of CCL28-C30AC80A at pH 7 (Fig. 4E–F, Blue). In a similar fashion to WT-CCL28 and CCL28-Δ80, acidification of the sample disrupts the tertiary fold of CCL28-C30AC80A (Fig. 4E, Right). However, in contrast to CCL28 variants with an intact disulfide bond between C30 and C80, addition of 150 mM NaCl fails to rescue this pH-dependent fold alteration for CCL28-C30AC80A (Fig. 4E–F, Red). Moreover, we observed a similar effect for pH- and salt-dependent fold alterations of CCL28-Δ79 (C30A), a variant lacking both the C- terminal extension and the additional disulfide bond (Fig. 4H–I).

Figure 4. NMR reveals that the non-conserved disulfide bond functions to stabilize the fold of CCL28.

(a) A schematic cartoon representation of C-terminally truncated CCL28 (i.e., CCL28-Δ80). (b) 1H, 15N HSQC spectra of CCL28-Δ80 at pH 7 (left) and pH 4 (right) in the presence (blue, red) and absence (black, grey) of salt. (c) Highlighting the W65 NεH peak position for CCL28-Δ80 spectra. (d) A schematic cartoon representation of the CCL28 variant lacking the additional disulfide bond (i.e., CCL28-C30AC80A). (e) 1H, 15N HSQC spectra of CCL28-C30AC80A at pH 7 (left) and pH 4 (right) in the presence (blue, red) and absence (black, grey) of salt. (f) Highlighting the W65 NεH peak position for CCL28-C30AC80 spectra. (g) A schematic cartoon representation of the CCL28 variant lacking the additional disulfide bond and C-terminal extension (i.e., CCL28-Δ79(C30A)). (h) 1H, 15N HSQC spectra of CCL28-Δ79(C30A) at pH 7 (left) and pH 4 (right) in the presence (blue, red) and absence (black, grey) of salt. (i) Highlighting the W65 NεH peak position for CCL28-Δ79(C30A) spectra.

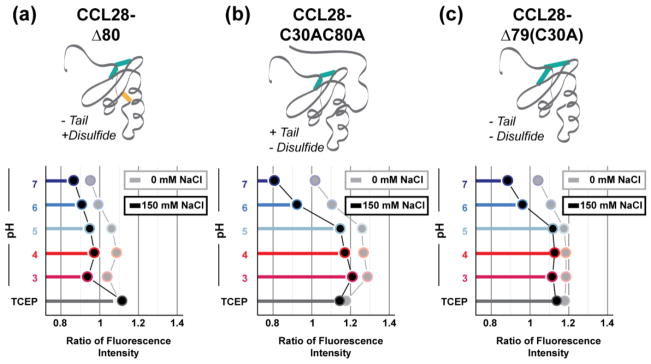

In addition to the aforementioned NMR experiments, we analyzed the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence emission spectra of CCL28-Δ80, CCL28-C30AC80A, and CCL28-Δ79 (C30A) (Fig. 5). Interestingly, we observed that the intrinsic fluorescence of W65 is only quenched in the presence of the additional disulfide bond. As CCL28-Δ80 lacks tyrosine residues that would shift the λmax to shorter wavelengths (as is seen in WT-CCL28), the folded λmax values of the C-terminal variants were between 330 nm (CCL28-C30AC80A) and 335 nm (CCL28-Δ79(C30A), CCL28-Δ80). In agreement with the NMR results, we observed a pH-dependent red shift in the λmax, and a consequent increase in the ratio of fluorescence intensities at the unfolded (348 nm) to folded λmax of each of the C-terminal variants of CCL28 (i.e., ratio > 1) (Fig. 5). Addition of 150 mM NaCl resulted in a decrease in the ratio of fluorescence intensities for each of the C-terminal variants of CCL28 (indicative of a more hydrophobic environment for the tryptophan residue), but variants lacking the additional disulfide bond only experienced a drastic shift (i.e., to ratio value < 1) at pH values > 5.

Figure 5. Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence reveals that the non-conserved disulfide bond functions to stabilize the fold of CCL28.

The ratio of fluorescence intensity at the unfolded (348 nm) and folded λmax for CCL28-Δ80 (a, folded λmax = 335 nm), CCL28-C30AC80A (b, folded λmax = 330 nm), and CCL28-Δ79(C30A) (c, folded λmax = 335 nm) in the presence and absence of salt (0 mM NaCl, light grey; 150mM NaCl, black) at pH 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, and pH 7 with the addition of TCEP (disulfide reducing agent, dark grey).

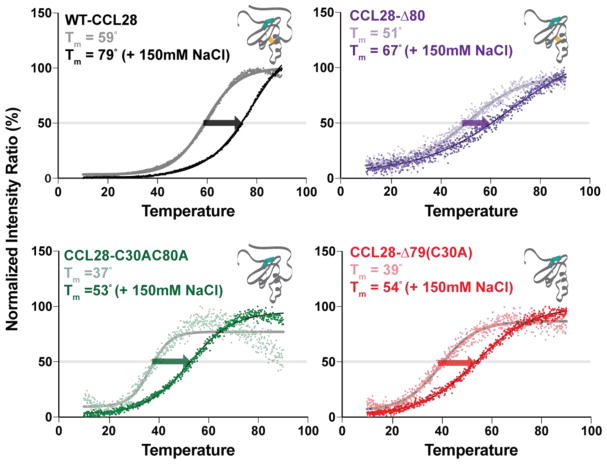

To further investigate the relative stability and salt sensitivity of the C-terminal variants of CCL28, a thermal denaturation assay was performed at pH 7, monitored by intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence (Fig. 6). For all proteins tested, addition of salt resulted in a rightward shift in the Tm, corroborating the NMR results suggesting the salt-induced stabilization of CCL28. For the variant lacking the additional disulfide bond (CCL28-C30AC80A), we observed a 23 C or 26 C reduction in the Tm compared to WT-CCL28 in the absence of presence of 150 mM NaCl, respectively, indicating destabilization of the tertiary fold (Fig. 6, Bottom). Indeed, the Tm values for CCL28-C30AC80A and CCL28-Δ79 (C30A) were near physiologic temperature (i.e., 37 C and 39 C, respectively). In contrast, truncation of the C-terminal domain alone minimally altered protein stability (Fig. 6, Top Right). Collectively, these results strongly suggest the additional disulfide bond acts to stabilize the tertiary fold of CCL28.

Figure 6. Thermal denaturation of CCL28 and Variants.

Results from a thermal denaturation assay as monitored by ratio of intensity at the unfolded (348 nm) and folded λmax for full-length (WT) CCL28 (black; folded λmax = 308 nm; Tm (No Salt) = 59.4 ± 0.1 C, Tm (150mM NaCl) = 78.8 ± 0.2 C), CCL28-Δ80 (purple; folded λmax = 335 nm; Tm (No Salt) = 51.1 ± 0.3 C, Tm (150mM NaCl) = 67.4 ± 1.0 C), CCL28-C30AC80A (green; folded λmax = 330 nm; Tm (No Salt) = 36.6 ± 0.3 C, Tm (150mM NaCl) = 52.5 ± 0.1 C), and CCL28-Δ79(C30A) (red; folded λmax = 335 nm; Tm (No Salt) = 39.4 ± 0.2 C, Tm (150mM NaCl) = 54.0 ± 0.1 C). Experiments were performed in the presence (dark curves) and absence (light curves) of 150 mM NaCl, with the salt-induced stabilization in melting temperature (Tm) indicated by an arrow. Tm values are indicated in each respective panel.

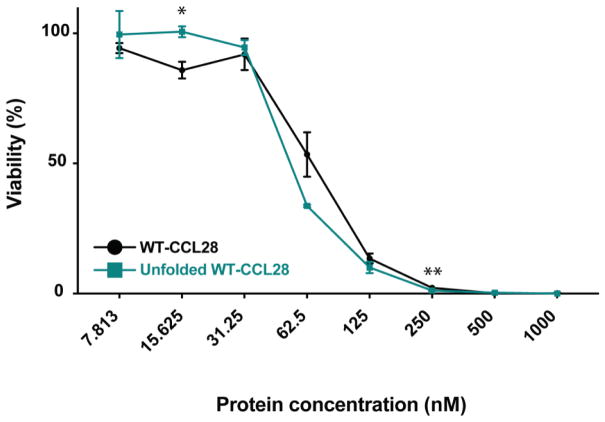

The Tertiary Fold of CCL28 is Not Necessary for Antifungal Activity

In a previous study, we identified that the tertiary fold of CCL28 is absolutely necessary for its in vitro chemotactic activity and its ability to drive the pathologic symptoms of asthma in vivo [24]. Since CCL28 exhibited unfolding behavior with relatively modest changes in solution conditions, we investigated the importance of its tertiary structure for antimicrobial activity. As expected, we found that recombinant human CCL28 is a potent antifungal agent against Candida albicans in an in vitro killing assay, in agreement with previous studies [11]. Interestingly, we found that unfolded CCL28 is as potent and efficacious as folded CCL28, indicating the tertiary fold of CCL28 is dispensable for its antifungal activity in vitro (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. The tertiary fold is not necessary for antifungal activity.

The results of an in vitro Candida killing assay performed at pH 7 in the absence of salt (0 mM NaCl) plotted as the concentration (μM) of CCL28 (or unfolded CCL28) by the percent viability remaining after CCL28 treatment. The WT-CCL28 response is plotted in black (IC50 = 70 ± 4 nM), and the response from unfolded WT-CCL28 is plotted in teal (IC50 = 54 ± 2 nM). Values represent mean ± SEM *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. Data shown represent the results of a single 96-well plate experiment with each protein concentration tested in triplicate.

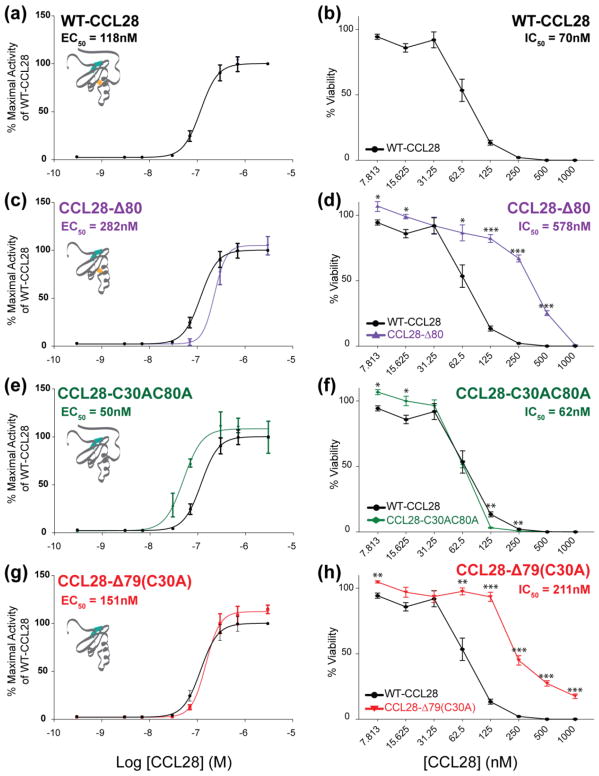

Removal of the C-terminal tail Reduces the Antifungal Potency of CCL28 while Minimally Disrupting GPCR activation

A previous study showed that CCL28 can kill Candida albicans and the unstructured C-terminal domain exerts antifungal activity in isolation [11]. For each of the C-terminal variants of CCL28, we measured CCR10-dependent calcium responses and candidacidal activity in vitro (Figure 8). We observed that although loss of the C-terminal domain only slightly decreases the potency of the calcium response at CCR10 (Fig. 8C), the antifungal potency of CCL28-Δ80 is decreased ~8-fold compared to WT-CCL28 (Fig. 8D). Mutational loss of the additional disulfide bond results in a ~2-fold increase in the potency of the calcium response at CCR10 (Fig. 8E), and no significant change in antifungal potency (Fig. 8F). Combinatorial loss of the C-terminal domain and additional disulfide bond (i.e., CCL28-Δ79 (C30A)) had no observable change on the potency of the CCR10-dependent calcium response in vitro (Fig. 8G), yet similar to C-terminal truncation alone (i.e., CCL28-Δ80), we observed a ~3-fold decrease in antifungal potency (Fig. 8H). Taken together, these results indicate that while the C-terminal domain of CCL28 has only minor effects on CCR10 activation in vitro, the unstructured C-terminal domain contributes significantly to in vitro antifungal potency.

Figure 8. Removal of the C-terminal tail significantly disrupts antifungal potency without interfering with CCR10 activation.

Left column - Results of calcium mobilization assays performed in triplicate on three separate days plotted as the log of CCL28 (or CCL28 variant) concentration (M) by the relative calcium response (RFU) as a percent activity of WT-CCL28 (i.e., 100% activity corresponds to WT-CCL28 at a concentration of 3 μM). The WT-CCL28 response curve (a) is plotted in black on all panels (LogEC50 = −6.93 ± 0.03 M). CCL28-Δ80 is plotted in purple (c; LogEC50 = −6.642 ± 0.045 M), CCL28-C30AC80A is plotted in green (e; LogEC50 = −7.299 ± 0.041 M), and CCL28-Δ79(C30A) is plotted in red (g; LogEC50 = −6.821 ± 0.035 M). EC50 values are noted in each respective panel. Right column - Results of in vitro Candida killing assays performed in triplicate plotted as the concentration (nM) of CCL28 (or CCL28 variant) by the percent viability remaining after CCL28 treatment. The WT-CCL28 response (b) is plotted in black on all panels (IC50 = 70 ± 4 nM). CCL28-Δ80 is plotted in purple (d; IC50 = 578 ± 325 nM), CCL28-C30AC80A is plotted in green (f; IC50 = 62 ± 2 nM), and CCL28-Δ79(C30A) is plotted in red (h; IC50 = 211 ± 12 nM). Values represent mean ± SEM *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Data shown represent the results of a single 96-well plate experiment with each protein concentration tested in triplicate.

The Antifungal Activity of CCL28 is Sensitive to pH and Salt

As our structural analysis revealed a pH- and salt-dependence of the tertiary fold of CCL28, we sought to determine the effects of pH and salt on the antifungal activity of CCL28. In agreement with previous studies, we observed that the antifungal activity of CCL28 is salt-dependent, whereby the presence of 150 mM NaCl completely inhibits the antifungal efficacy of CCL28 in vitro, for both WT-CCL28 (Fig. 9A) and CCL28-C30AC80A (Fig. 9B). However, we also found that the antifungal potency of CCL28 is sensitive to changes in pH. At low pH (i.e., pH 4), we observed an increase in the antifungal potency for WT-CCL28 (i.e., ~3-fold) and CCL28-C30AC80A (i.e., ~4-fold) (Fig. 9A, 9B). Even at low pH, addition of salt completely inhibited the antifungal efficacy of WT-CCL28 and CCL28-C30AC80A (Fig. 9A, 9B). To investigate whether the observed pH-dependence of the antifungal potency of CCL28 was related to the tertiary fold, we tested the pH-dependence of the chemically unfolded WT-CCL28 variant against both folded WT-CCL28 (Fig. 9C) and CCL28-C30AC80A (Fig. 9D). We observed that similar to the folded proteins, unfolded WT-CCL28 experienced an increase in antifungal potency at low pH (i.e., pH 4, Fig. 9C–D, maroon curve). Collectively, these results suggest that a decrease in pH independently increases the antifungal potency of CCL28, regardless of the tertiary fold. As the antimicrobial activities of chemokines and other antimicrobial peptides are thought to be highly dependent on charge [3,5], and as CCL28 contains a large number of histidine residues (i.e., 11 histidine residues out of 108 total residues), the decrease in pH may increase the antifungal potency by protonating histidine residues.

Figure 9. The antifungal activity of CCL28 is sensitive to changes in pH and salt.

Results of in vitro Candida killing assays plotted as the concentration (nM) of CCL28 (or CCL28 variant) by the percent viability remaining after CCL28 treatment. (a–b) Testing the effect of buffer pH and NaCl on the ability of WT-CCL28 (a; pH 7 IC50 = 47 ± 3 nM, pH 4 IC50 = 16 ± 2 nM) and CCL28-C30AC80 (b; pH 7 IC50 = 30 ± 3 nM, pH 4 IC50 = 7.1 ± 0.3 nM) to kill Candida albicans in vitro. Salt inhibits antifungal efficacy regardless of pH. (c) A chemically unfolded variant of WT-CCL28 is more potent at pH 4 (red curve; IC50 = 15 ± 1 nM) than at pH 7 (teal curve; IC50 = 38 ± 2 nM) similar to WT-CCL28 (pH 7 IC50 = 34 ± 2 nM, pH 4 IC50 = 10 ± 1 nM). (d) A chemically unfolded variant of WT-CCL28 is more potent at pH 4 (red curve; IC50 ~ 15 nM) than at pH 7 (teal curve; IC50 = 34 ± 2 nM) similar to CCL28-C30AC80A (pH 7 IC50 = 27 ± 1 nM, pH 4 IC50 = 7 ± 1 nM). Each panel represents the results of a single 96-well plate experiment with each protein concentration tested in triplicate. Each protein and buffer condition was run on two separate plates, and we observed identical curve shape across multiple experiments.

DISCUSSION

It is becoming increasingly recognized that chemokines have functions beyond the direction of cell migration, and one such function is direct antimicrobial activity against invading pathogens. Indeed, the immunologic functions of both chemokines and antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) have considerable overlap, with members of each family acting as both chemoattractants and antimicrobial agents [25–27]. The physiologic significance of the antimicrobial functions of chemokines remains unclear, but it has been proposed that they may allow for a more robust immunologic response to microbial infection in vivo [27]. Additionally, it has been suggested that the antimicrobial activities of homeostatic chemokines may be important for controlling commensal microbial populations [5]. For example, a recent study by Matsuo et al. revealed that colonic microbiota of CCL28-deficient mice was significantly altered compared to wild-type controls, a finding that may be related to the direct antimicrobial activity of CCL28 [28].

In this study, we found that the CCL28 native state structure is sensitive to changes in pH and salt concentration, whereby the tertiary fold of CCL28 is destabilized at low pH (i.e., pH <5.5) and stabilized by the addition of 150 mM NaCl (Figure 10). Although this type of pH- and salt-dependent structural lability for the tertiary fold of a chemokine is unique, the quaternary structures of many chemokines have been shown to be highly sensitive to changes in pH and salt. For example, CXCL12 exists in a monomer-dimer equilibrium, but the dimer dissociation Kd has been shown to be highly dependent on pH and salt whereby the monomeric form is favored in acidic environments [29]. Similarly, CCL11 has been shown to exist in a monomer-dimer equilibrium at physiologic pH (i.e., pH 7) but forms a stable monomer in an acidic environment (i.e., pH 5) [30]. CCL5 exists as a stable monomer at low pH (i.e., pH 2.5), but forms large oligomers and even aggregates at more neutral pH (i.e., pH > 3.5) [31,32]. CCL4 exists as a discrete and stable dimer in acidic environments (i.e., pH 2.5) but similarly forms large aggregates at pH > 3.5 [33,34]. The metamorphic chemokine XCL1 experiences a salt- and temperature-sensitive change in tertiary and quaternary structure, whereby conditions of high salt and low temperature (i.e., 200 mM NaCl, 10 C) favor the formation of a monomer with the traditional chemokine tertiary fold, and conversely conditions of low salt and high temperature (i.e., 0 mM NaCl, 40 C) favor the formation of a non-canonical dimer [35,36]. Although XCL1 experiences such a drastic conformational change with alterations in salt and temperature, it is insensitive to changes in pH (i.e., between pH 5 and 8) as it contains no histidine residues [35]. CCL28 has the highest number of histidine residues of any chemokine (i.e., 11 histidine residues), and over half of CCL28’s histidine residues are located in the disordered C-terminal tail. As our results indicate that CCL28 undergoes a pH-dependent fold change between pH 6 and 4, it is possible that protonation of histidine residues could be a driving factor for CCL28’s pH sensitivity, similar to what has been reported for the pH-sensitive oligomerization of CXCL12 [29].

Figure 10.

A model for the pH- and salt-dependent structural lability of CCL28.

The tertiary fold of chemokines is largely stabilized by 2 characteristic disulfide bonds which link the flexible N-terminus to the chemokine core. For some chemokines, such as CXCL8, loss of either of these canonical disulfide bonds results in the disruption of tertiary structure and consequent loss of biologic activity [37,38]. However, this doesn’t seem to be the case for all chemokines, as chemical reduction and subsequent alkylation of the cysteine residues in CXCL10 did not alter CXCL10’s biologic activity [39]. CCL28 is one of five human chemokines that have a third, non-canonical disulfide bond (i.e., CCL1, CCL15, CCL21, CCL23, and CCL28). Structural and functional analysis of CCL28 variants lacking this non-canonical disulfide bond (i.e., CCL28-C30AC80A and CCL28-Δ79(C30A)) indicates that it functions primarily to stabilize CCL28’s tertiary fold, with only a minimal effect on either CCR10 activation or antifungal activity. A previous report of CCL15 revealed that mutational elimination of its non-canonical disulfide bond had only minor effects on its tertiary fold, indicating that the large structural changes observed for CCL28 upon elimination of its additional disulfide bond are unique [21].

In addition to having a third, non-canonical disulfide bond, CCL28 has an extended C-terminal domain of 28 residues which follows the most C-terminal cysteine residue (cysteine 80). Our structural and functional analyses revealed that the extended C-terminal domain of CCL28 is unstructured and dynamic, and that it has a minimal effect on either the structural stability of CCL28 or CCL28’s activation of the chemokine receptor CCR10 in vitro. Our results suggest that the C-terminal tail of CCL28 functions primarily to drive the antimicrobial activity of CCL28, a finding consistent with previous reports [11,17]. Hieshima et al. first established the significance of the C-terminal domain in CCL28’s antifungal activity by showing that a peptide of the C-terminal domain alone (i.e., residues 81–108) retains much of the antifungal activity of the full-length protein, with only a two-fold decrease in antifungal potency [11]. In the present study, we analyzed the in vitro antifungal activity of a CCL28 variant lacking the C-terminal domain (i.e., CCL28-Δ80) and found that it has an eight-fold decrease in antifungal potency compared to the full-length protein, corroborating the notion that the C-terminal domain is the primary contributor to the antifungal activity of CCL28.

In our efforts to understand how the pH- and salt-dependent structural lability of CCL28 may be altering its function, we observed that the antifungal activity of CCL28 is similarly pH- and salt-dependent (Figure 10). While it has been previously established that high salt conditions disrupt the antimicrobial effects of CCL28 and other chemokines [2,11], the effect of pH on the antifungal activity of CCL28 has not been previously described. We observed that low pH (i.e. pH 4) actually enhances the antifungal potency of CCL28, and that this pH-dependent increase in antifungal potency was independent of CCL28’s tertiary fold. As Candida albicans and other fungal species can survive in more acidic environments including the vagina (pH 4-4.5) and phagolysosomes [40,41], the ability of CCL28 to remain efficacious at low pH is important for understanding its role in controlling Candida pathogenesis and development of CCL28 as a therapeutic agent [42,43].

In summary, here we report the first structure of CCL28, solved by NMR spectroscopy. We observed that the tertiary fold of CCL28 is sensitive to changes in pH and salt across a physiologically relevant range, and that the additional disulfide bond acts to stabilize the tertiary fold of CCL28. In addition, we found that the unstructured C-terminal tail does not significantly alter CCR10 activation or structural stability of CCL28, but consistent with other reports, the C-terminal tail has a large effect on the antifungal activity of CCL28. Finally, we show that the tertiary fold of CCL28 is not necessary for its antifungal activity, and that the antifungal potency of CCL28 is enhanced at low pH. We propose that the pH-dependent structural lability of CCL28 is important for its role as both a chemoattractant and antimicrobial agent (Figure 10).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein Production and Purification

The human CCL28 gene lacking its signal peptide (Genescript; UniProt ID: Q9NRJ3 [44]) was cloned into a previously described pET28a vector [45–47]. Isotopically labeled protein used for NMR structural studies was produced using M9 minimal media containing 15NH4Cl and [U-13C]-glucose as previously described [29]. The protein was isolated, refolded, and purified using established protocols [29]. Purity, identity, and molecular weight of the purified protein were verified by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and linear trap quadrupole (LTQ) mass spectrometry.

Protein Unfolding and Alkylation

Purified recombinant CCL28 was diluted to a concentration of 1mg/mL in a buffer containing 100 mM NH4HCO3 and 6M Urea at pH 7.8. All disulfide bonds were reduced by addition of dithiothreitol (DTT) to a final concentration of 5 mM and incubated for 45 minutes at 37° C with shaking. All cysteine residues were alkylated by addition of iodoacetamide to a final concentration of 20 mM and incubated in the dark for 60 minutes at room temperature. The alkylation reaction was quenched by the addition of 5 mM DTT. The alkylated product was then dialyzed (with buffer changed 3x) in 100 mM NH4HCO3. The sample precipitated during the dialysis but was brought into solution by dropping the pH to ~6.2. The solubilized alkylated product was filtered and subsequently purified by HPLC. Molecular weight of the product was confirmed by LTQ mass spectrometry.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

Heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) experiments were performed on a Bruker Avance 500 MHz spectrometer equipped with a triple-resonance cryogenic probe. One-dimensional 1H NMR and two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC NMR experiments were collected at 25 °C (specified in text) using a sample with 250 μM protein in a solution of 25 mM deuterated MES, 10% D2O, and 0.02% NaN3. For pH titration HSQC experiments, pH ranged from 4 to 7 (specified in text). NMR data were processed with NMRPipe [48] and XEASY [49] was used to visualize spectra.

Structure Determination

The NMR experiments for structure determination of CCL28 were performed on a Bruker DRX 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a 1H, 15N, 13C TXI cyroprobe at 298K. The NMR spectra for structural determination were obtained using a sample with 700μM recombinant human CCL28 protein in a solution of 25mM deuterated MES, 10% D2O, and 0.02% NaN3 at pH 6.2. Resonance assignments (1H, 15N, and 13C) for the backbone of CCL28 were obtained as previously described [24]. Resonance assignments (1H, 15N, and 13C) for the amino acid side-chains of CCL28 were completed using the following additional experiments: HBHACONH, HCCH-TOCSY, HCCONH. Distance constraints were obtained from the following experiments: 3D 15N-edited NOESY-HSQC, 3D 13C-edited NOESY-HSQC, and 13C(aromatic)-edited NOESY-HSQC. Backbone dihedral angle constraints were generated by TALOS+ using 1Hα, 13Cα, 13Cβ, 13C’, and 15N chemical shift information [20]. NMR data were processed with NMRPipe [24] and XEASY [21] was used to visualize spectra for assignment and manual refinement. The NOEASSIGN module of the torsion angle dynamics program CYANA 2.1 was used to calculate NOE distance constraints and initial structures were generated using the CANDID module of CYANA [13]. Iterative manual refinement followed to eliminate remaining constraint violations. Further structural refinement was performed on the 20 CYANA conformers with the lowest target function using XPLOR-NIH explicit water refinement [14,15].

Protein Data Bank and Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank Deposition

NMR parameters for the CCL28 structure have been deposited in the Biologic Magnetic Resonance Bank (BMRB) with accession number 30445. The structure of CCL28 has been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with PDB ID 6CWS.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation

The average, minimized structure from the NMR structural ensemble of CCL28 was prepared for simulation by using the Protein Preparation Wizard of Maestro (Schrödinger) to perform H-bond optimization and protein minimization [50]. The System Builder in Maestro (Schrödinger) was then used to place CCL28 into a box of explicit solvent, with sodium and chloride ions added to neutralize the system and reach a final concentration of 150 mM. The viparr and build_constraints utilities of Desmond were used to adjust the force field parameters to utilize the CHARMM 36 force field and the TIP3P water model [51,52]. The system was equilibrated and the molecular dynamics simulation was performed with randomized starting velocities for 500 ns (with a 500 picosecond recording interval) at 300K and 1.01325 bar in the NPT ensemble using a Nose-Hoover thermostat and a Martyna-Tobias-Klein barostat with a 2.0 picosecond relaxation time. The resulting trajectory was analyzed using Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD) [53]and the R package Bio3D [54].

Intrinsic Tryptophan Fluorescence

Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence emission spectra were measured in a Photon Technology International (PTI) spectrofluorometer in a temperature-controlled cuvette at 25°C containing 200 μL of a 0.5 mg/mL protein sample. All protein samples were in a buffer of 25 mM MES, with pH values between 2–7, and either with or without 150 mM NaCl (specified in text). An excitation wavelength of 283 nm with a 4 nm excitation slit width was used and fluorescence emission was collected between 290–400 nm with a 6 nm emission slit width [55]. Raw emission intensity values were plotted and the λmax values were calculated using a custom R script. For thermal denaturation experiments, temperature was steadily increased from 10°C to 90°C by an external circulating water bath. An excitation wavelength of 283 nm (4 nm excitation slit width) was used and the fluorescence emission intensity was measured at the folded (λmax = 308–340 nm, depending on variant; specified in text) and unfolded (λmax = 348 nm) wavelengths (6 nm emission slit width). The ratio of emission intensity at the unfolded and folded wavelengths was calculated and plotted using Prism (GraphPad). Melting temperatures (Tm values) were determined by fitting the data to a Boltzmann sigmoidal equation using Prism (GraphPad).

Calcium Mobilization

Ready-to-Assay® Chem-1 cells (Eurofins) expressing human CCR10 were prepared to assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were incubated at 37°C, 5%CO2 for 24 hours. Following the 24-hour incubation period, calcium flux assays were performed as previously described [56]. Experiments were recorded in triplicate on three separate days. The averages from each experiment were normalized to the maximal response of WT-CCL28 (100% activity). Data were plotted on a log scale and fit to a variable slope four parameter equation in Prism (GraphPad) to calculate EC50 values.

Candida Assays

One single clone of the Candida albicans strain CAF2-1 was cultured in yeast peptone dextrose (YPD) medium at 30°C and 250 rpm for 16–20 hours. Cultured Candida was then washed twice in 1mM potassium phosphate buffer (PPB) and diluted to 10mL stock at final concentration of 5X10^4 cell/mL for each buffer used: 1mM PPB at pH 7, 1mM PPB at pH 7 with 150 mM NaCl, 1mM PPB at pH 4, and 1mM PPB at pH 4 with 150 mM NaCl. Lyophilized powder of wild type (WT) CCL28 and CCL28 variants (i.e., CCL28-Δ80, CCL28-C30AC80A, CCL28-Δ79(C30A), and unfolded CCL28) were reconstituted in 1mM PPB to a final concentration of 400uM and aliquoted to 50 μl vials and stored at -20°C. The Candida killing assay was adapted from previously described methods (Hieshima et al, 2003). Serial dilutions of protein were mixed 1:1 with 5 x 104 cells/ml Candida stock in each respective buffer to a final volume of 100 μl in a 96 well plate. Each condition was tested in triplicate and assays were performed at least in duplicate. No-protein controls were set up with each tested buffer condition. The plate was incubated at room temperature for 2 hours with gentle shaking (50–60 rpm). After appropriate dilutions with each respective buffer, solutions were plated on YPD agar plates and incubated 48 hours at 30°C. Colonies were enumerated and percentage viability was calculated in comparison to the colony number of the no-protein controls of the respective buffer. Data were fit to a variable slope four parameter equation in Prism (GraphPad) to calculate IC50 values. Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test. Significance was set at p < 0.05. Data shown in figures represent the results of a single 96-well plate experiment with each protein concentration tested in triplicate. While individual plates revealed differences in IC50 value, trends were consistent across plates.

HIGHLIGHTS.

CCL28 is a chemokine with chemoattractant and antimicrobial capabilities

CCL28 has an extended, dynamic C-terminal tail and an additional disulfide bond

CCL28 unfolds at low pH, but the fold can be stabilized by salt

The antifungal activity of CCL28 is enhanced by low pH but abrogated by salt

CCL28’s pH-dependent structural lability may be important for antifungal activity

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Davin Jensen and Amanda Nevins for molecular cloning of WT-CCL28 and the CCL28 variants. This research was completed in part with computational resources and technical support provided by the Research Computing Center at the Medical College of Wisconsin. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants F30 HL134253 (MAT), K08 DE026189 (ARH), R01 AI120655 (BFV). ARH was also supported by the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin Research Institute. MAT is a member of the NIH supported (T32 GM080202) Medical Scientist Training Program at MCW.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS: BFV and ARH conceived the project. MAT and JH performed and analyzed all experiments. MAT and FCP collected and analyzed all NMR data, as well as calculated and validated the NMR structure. MAT wrote the original manuscript draft. MAT, BFV, and ARH revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript before submission.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS: BFV has ownership interests in Protein Foundry, LLC.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Stone MJ, Hayward JA, Huang C, Huma ZE, Sanchez J. Mechanisms of Regulation of the Chemokine-Receptor Network. Ijms. 2017;18:342. doi: 10.3390/ijms18020342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yung SC, Murphy PM. Antimicrobial chemokines. Front Immunol. 2012;3:276. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahlapuu M, Håkansson J, Ringstad L, Björn C. Antimicrobial Peptides: An Emerging Category of Therapeutic Agents. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2016;6:194. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang G. Human antimicrobial peptides and proteins. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2014;7:545–594. doi: 10.3390/ph7050545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolf M, Moser B. Antimicrobial activities of chemokines: not just a side-effect? Front Immunol. 2012;3:213. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bahar AA, Ren D. Antimicrobial peptides. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2013;6:1543–1575. doi: 10.3390/ph6121543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Weerden NL, Bleackley MR, Anderson MA. Properties and mechanisms of action of naturally occurring antifungal peptides. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:3545–3570. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1260-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swidergall M, Ernst JF. Interplay between Candida albicans and the antimicrobial peptide armory. Eukaryotic Cell. 2014;13:950–957. doi: 10.1128/EC.00093-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maerki C, Meuter S, Liebi M, Mühlemann K, Frederick MJ, Yawalkar N, et al. Potent and broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity of CXCL14 suggests an immediate role in skin infections. J Immunol. 2009;182:507–514. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang D, Chen Q, Hoover DM, Staley P, Tucker KD, Lubkowski J, et al. Many chemokines including CCL20/MIP-3alpha display antimicrobial activity. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:448–455. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0103024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hieshima K, Ohtani H, Shibano M, Izawa D, Nakayama T, Kawasaki Y, et al. CCL28 has dual roles in mucosal immunity as a chemokine with broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity. The Journal of Immunology. 2003;170:1452–1461. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helmerhorst EJ, Van't Hof W, Veerman EC, Simoons-Smit I, Nieuw Amerongen AV. Synthetic histatin analogues with broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity. Biochem J. 1997;326(Pt 1):39–45. doi: 10.1042/bj3260039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hernández-Ruiz M, Zlotnik A. Mucosal Chemokines. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2017;37:62–70. doi: 10.1089/jir.2016.0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan J, Kunkel EJ, Gosslar U, Lazarus N, Langdon P, Broadwell K, et al. A novel chemokine ligand for CCR10 and CCR3 expressed by epithelial cells in mucosal tissues. The Journal of Immunology. 2000;165:2943–2949. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.2943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang W, Soto H, Oldham ER, Buchanan ME, Homey B, Catron D, et al. Identification of a novel chemokine (CCL28), which binds CCR10 (GPR2) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:22313–22323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001461200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Söbirk SK, Mörgelin M, Egesten A, Bates P, Shannon O, Collin M. Human chemokines as antimicrobial peptides with direct parasiticidal effect on Leishmania mexicana in vitro. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e58129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu B, Wilson E. The antimicrobial activity of CCL28 is dependent on C-terminal positively-charged amino acids. Eur J Immunol. 2009;40:186–196. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conti HR, Gaffen SL. IL-17-Mediated Immunity to the Opportunistic Fungal Pathogen Candida albicans. J Immunol. 2015;195:780–788. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandez EJ, Lolis E. Structure, Function, and Inhibition of Chemokines. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2002;42:469–499. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.091901.115838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keizer DW, Crump MP, Lee TW, Slupsky CM, Clark-Lewis I, Sykes BD. Human CC chemokine I-309, structural consequences of the additional disulfide bond. Biochemistry. 2000;39:6053–6059. doi: 10.1021/bi000089l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sticht H, Escher SE, Schweimer K, Forssmann WG, Rösch P, Adermann K. Solution structure of the human CC chemokine 2: A monomeric representative of the CC chemokine subtype. Biochemistry. 1999;38:5995–6002. doi: 10.1021/bi990065i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Love M, Sandberg JL, Ziarek JJ, Gerarden KP, Rode RR, Jensen DR, et al. Solution structure of CCL21 and identification of a putative CCR7 binding site. Biochemistry. 2012;51:733–735. doi: 10.1021/bi201601k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajarathnam K, Li Y, Rohrer T, Gentz R. Solution structure and dynamics of myeloid progenitor inhibitory factor-1 (MPIF-1), a novel monomeric CC chemokine. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:4909–4916. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005085200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas MA, Buelow BJ, Nevins AM, Jones SE, Peterson FC, Gundry RL, et al. Structure-Function Analysis of CCL28 in the Development of Post-viral Asthma. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:4528–4536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.627786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCormick TS, Weinberg A. Epithelial cell-derived antimicrobial peptides are multifunctional agents that bridge innate and adaptive immunity. Periodontol 2000. 2010;54:195–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2010.00373.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mansour SC, Pena OM, Hancock REW. Host defense peptides: front-line immunomodulators. Trends Immunol. 2014;35:443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crawford MA, Margulieux KR, Singh A, Nakamoto RK, Hughes MA. Mechanistic insights and therapeutic opportunities of antimicrobial chemokines. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuo K, Nagakubo D, Yamamoto S, Shigeta A, Tomida S, Fujita M, et al. CCL28-Deficient Mice Have Reduced IgA Antibody-Secreting Cells and an Altered Microbiota in the Colon. J Immunol. 2017:ji1700037. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veldkamp CT. The monomer-dimer equilibrium of stromal cell-derived factor-1 (CXCL 12) is altered by pH, phosphate, sulfate, and heparin. Protein Science. 2005;14:1071–1081. doi: 10.1110/ps.041219505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crump MP, Spyracopoulos L, Lavigne P, Kim KS, Clark-Lewis I, Sykes BD. Backbone dynamics of the human CC chemokine eotaxin: fast motions, slow motions, and implications for receptor binding. Protein Science. 1999;8:2041–2054. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.10.2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X, Watson C, Sharp JS, Handel TM, Prestegard JH. Oligomeric structure of the chemokine CCL5/RANTES from NMR, MS, and SAXS data. Structure. 2011;19:1138–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skelton NJ, Aspiras F, Ogez J, Schall TJ. Proton NMR assignments and solution conformation of RANTES, a chemokine of the C-C type. Biochemistry. 1995;34:5329–5342. doi: 10.1021/bi00016a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lodi PJ, Garrett DS, Kuszewski J, Tsang ML, Weatherbee JA, Leonard WJ, et al. High-resolution solution structure of the beta chemokine hMIP-1 beta by multidimensional NMR. Science. 1994;263:1762–1767. doi: 10.1126/science.8134838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ren M, Guo Q, Guo L, Lenz M, Qian F, Koenen RR, et al. Polymerization of MIP-1 chemokine (CCL3 and CCL4) and clearance of MIP-1 by insulin-degrading enzyme. Embo J. 2010;29:3952–3966. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tuinstra RL, Peterson FC, Kutlesa S, Elgin ES, Kron MA, Volkman BF. Interconversion between two unrelated protein folds in the lymphotactin native state. Proc Natl Acad Sci USa. 2008;105:5057–5062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709518105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuloğlu ES, McCaslin DR, Markley JL, Volkman BF. Structural rearrangement of human lymphotactin, a C chemokine, under physiological solution conditions. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:17863–17870. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200402200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clark-Lewis I, Dewald B, Loetscher M, Moser B, Baggiolini M. Structural requirements for interleukin-8 function identified by design of analogs and CXC chemokine hybrids. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:16075–16081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rajagopalan L, Chin CC, Rajarathnam K. Role of intramolecular disulfides in stability and structure of a noncovalent homodimer. Biophys J. 2007;93:2129–2134. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.108761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crow M, Taub DD, Cooper S, Broxmeyer HE, Sarris AH. Human recombinant interferon-inducible protein-10: intact disulfide bridges are not required for inhibition of hematopoietic progenitors and chemotaxis of T lymphocytes and monocytes. J Hematother Stem Cell Res. 2001;10:147–156. doi: 10.1089/152581601750098417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Danby CS, Boikov D, Rautemaa-Richardson R, Sobel JD. Effect of pH on in vitro susceptibility of Candida glabrata and Candida albicans to 11 antifungal agents and implications for clinical use. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1403–1406. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05025-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Erwig LP, Gow NAR. Interactions of fungal pathogens with phagocytes. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14:163–176. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2015.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chaillot J, Tebbji F, García C, Wurtele H, Pelletier R, Sellam A. pH-Dependant Antifungal Activity of Valproic Acid against the Human Fungal PathogenCandida albicans. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1956. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Foley EJ, Herrmann F, Lee SW. The effects of pH on the antifungal activity of fatty acids and other agents; preliminary report. J Invest Dermatol. 1947;8:1–3. doi: 10.1038/jid.1947.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.The UniProt Consortium. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D158–D169. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Veldkamp CT, Seibert C, Peterson FC, De la Cruz NB, Haugner JC, Basnet H, et al. Structural Basis of CXCR4 Sulfotyrosine Recognition by the Chemokine SDF-1/CXCL12. Science Signaling. 2008;1:ra4–ra4. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.1160755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Veldkamp CT, Ziarek JJ, Su J, Basnet H, Lennertz R, Weiner JJ, et al. Monomeric structure of the cardioprotective chemokine SDF-1/CXCL12. Protein Sci. 2009;18:1359–1369. doi: 10.1002/pro.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takekoshi T, Ziarek JJ, Volkman BF, Hwang ST. A locked, dimeric CXCL12 variant effectively inhibits pulmonary metastasis of CXCR4-expressing melanoma cells due to enhanced serum stability. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2012;11:2516–2525. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson E, Butcher EC. CCL28 controls immunoglobulin (Ig)A plasma cell accumulation in the lactating mammary gland and IgA antibody transfer to the neonate. J Exp Med. 2004;200:805–809. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hieshima K, Kawasaki Y, Hanamoto H, Nakayama T, Nagakubo D, Kanamaru A, et al. CC chemokine ligands 25 and 28 play essential roles in intestinal extravasation of IgA antibody-secreting cells. The Journal of Immunology. 2004;173:3668–3675. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sastry GM, Adzhigirey M, Day T, Annabhimoju R, Sherman W. Protein and ligand preparation: parameters, protocols, and influence on virtual screening enrichments. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2013;27:221–234. doi: 10.1007/s10822-013-9644-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Best RB, Zhu X, Shim J, Lopes PEM, Mittal J, Feig M, et al. Optimization of the additive CHARMM all-atom protein force field targeting improved sampling of the backbone φ, ψ and side-chain χ(1) and χ(2) dihedral angles. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012;8:3257–3273. doi: 10.1021/ct300400x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bowers K, Chow E, Xu H, Dror R, Eastwood M, Gregersen B, et al. Scalable Algorithms for Molecular Dynamics Simulations on Commodity Clusters. ACM/IEEE SC 2006 Conference (SC'06); IEEE; n.d. pp. 43–43. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:33–8. 27–8. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grant BJ, Rodrigues APC, ElSawy KM, McCammon JA, Caves LSD. Bio3d: an R package for the comparative analysis of protein structures. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2695–2696. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morteau O, Gerard C, Lu B, Ghiran S, Rits M, Fujiwara Y, et al. An indispensable role for the chemokine receptor CCR10 in IgA antibody-secreting cell accumulation. J Immunol. 2008;181:6309–6315. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ziarek JJ, Getschman AE, Butler SJ, Taleski D, Stephens B, Kufareva I, et al. Sulfopeptide Probes of the CXCR4/CXCL12 Interface Reveal Oligomer-Specific Contacts and Chemokine Allostery. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:1955–1963. doi: 10.1021/cb400274z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]