Abstract

Objective

Half of the TB patients in India seek care from private providers resulting in incomplete notification, varied quality of care and out-of-pocket expenditure. The objective of this study was to describe the characteristics of TB patients who remain outside the coverage of treatment in public health services.

Methods

Cross-sectional data from National Family Health Survey-4 (2015–16) were analyzed using logistic regression analysis. TB treatment was the dependent variable. Sociodemographic factors and place where households generally seek treatment were independent variables.

Results

Prevalence of self-reported TB was 308.17/100,000 population (95%CI:309.44–310.55/100000 population) and 38.8% (95%CI: 36.5%–41.1%) of TB patients were outside care of public health services − 3.3% did not seek treatment and 35.3% accessed treatment from private sector. Factors associated with not seeking treatment were age <10 years [OR=3.43;95 %CI (1.52–7.77);p=0.00]; no/preschool education [OR=1.82;95%CI(1.10–3.34);p=0.02]; poorest wealth index [OR=1.86;95%CI(1.01–3.34);p=0.04] and household’s general rejection of the public sector when seeking health care [OR=1.69;95%CI(1.69–2.26);p=0.00]. Factors associated with seeking treatment from private providers were female sex [OR=1.29; 95%CI(1.11-1.50); p=0.001], younger age of the patient [OR=2.39; 95%CI (1.62–3.53); p=0.00], higher education [OR=1.82; CI (1.11–2.98); p=0.02] and household’s general rejection of the public sector when seeking health care [OR=4.56; 95%CI (3.95–5.27); p=0.00]. Patients from households reporting ‘poor quality of care’ as the reason for not generally preferring public health services were more likely (OR=1.48, 95%CI=1.19–1.65; p=00) to access private treatment.

Conclusion

The study provides insights for efforts to involve the private health sector for accurate surveillance and patient groups requiring targeted interventions for linking them to the national program.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, RNTCP, Public health services, Private health services, Notification

INTRODUCTION

With a TB (tuberculosis) incidence rate of 211 per 100,000 population, India has the largest number of incident TB cases globally [1]. The Revised National Tuberculosis Control Program (RNTCP), which was launched in 1997 and achieved nationwide coverage in March 2016, aims to achieve universal access to affordable and quality care for all TB patients in the country [2]. However, studies have estimated that 40%–53% of TB patients in India are treated in the private sector [3, 4].

In India health care services are provided by a multitude of agencies in the public, private and voluntary health sectors. The public sector provides services in rural areas through a three-tier system of sub-centers, primary health centers and community health centers and in urban areas through the urban health centers and hospitals run by local government bodies. The private sector is a major provider of curative health services in the urban areas. For tuberculosis, the government provides free diagnostic and treatment services through its national program, the RNTCP, which has more than 16,000 microscopy centers and more than 600,000 DOTS (Directly Observed treatment- Short course) providers. Though private and NGO (Non-Government Organization) sectors can also participate in case finding and treatment activities under the public-private partnership initiative under RNTCP, treatment in the private sector usually entails out-of-pocket expenditure for diagnosis and treatment [5]. In spite of the fact that tuberculosis has been a notifiable disease since 2012, many patients treated in the private sector are not notified to the national surveillance system [1, 6], leading to an underestimation of the burden of disease. For patients, the quality and standards for appropriate treatment regimens in the private sector are often inadequate and varied [7–10].

Considering these implications we analyzed the data collected during the National Family Health Survey - 4 (NFHS-4) to understand the characteristics of the TB patients who remain outside the coverage of treatment in public health services. The number and characteristics of these missed cases will help policy makers to understand the magnitude and nature of TB as a public health problem and provide insights for linking these patients to the national program.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

We obtained the data for this study from the NFHS − 4, a large-scale, multi-round survey conducted in a nationally representative probability sample of households covering all 640 districts in 29 states and 7 union territories throughout India [11]. This cross-sectional survey was conducted in 2015–16 and was designed along the lines of the Demographic and Health Surveys for collecting demographic, socioeconomic and health information [12]. The sample is a stratified two-stage sample with an overall response rate of 98%. The analysis presented here focuses on persons who self-reported TB in the household in response to survey questions.

Dependent variable

In NFHS-4, trained interviewers visited the households in the representative sample and any adult member of the household who was capable of providing information for the Household Questionnaire served as the respondent. Generally questions were asked to a single individual, but if necessary the interviewer consulted other members of the household for specific information [12]. The following questions were asked to the respondent about persons suffering from tuberculosis in the household:

Any usual resident who suffers from tuberculosis?

Has he/she received medical treatment for the tuberculosis? If yes, where did he/she go for treatment?

The response options were categorized as: Not receiving treatment; receiving treatment from public sector only, receiving treatment from private health sector only, receiving treatment from both public and private sector and don’t know.

The data about the diagnosis of TB and how the patient received treatment were collected during the household survey without any cross-checking documentation from the public/private sector, as this was not within the scope of standard NFSH-4 data collection methods. The dependent variables were ‘treatment sought’ and ‘type of health service provider’ from whom treatment was sought for tuberculosis.

Independent variables

The independent variables considered in this study were age, gender [male, female], education [no education, primary, secondary, higher education], wealth index [poorest, poorer, middle, richer, richest], residence [urban, rural], household structure [nuclear, non-nuclear] and type of health service provider from where the household members generally seek treatment. For type of health service providers where household members generally go for treatment, ‘NGO/Trust Hospital clinic, private health sector’ were grouped into ‘others’ group and compared with ‘public health sector’. The reasons for not generally seeking care from public health services were considered.

Data collection

The survey was conducted using an interviewer-administered questionnaire in the native language of the respondent [12]. The questionnaires were pretested and the field staff involved in data collection were trained. Multiple levels of monitoring and supervision of the fieldwork, use of Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing, daily transfer of field data to the nodal agency, extensive data quality checks and provision of real-time feedback to field agencies ensured data quality.

Statistical analysis

Analysis was conducted with Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 21 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY, United States). Descriptive statistics such as frequency and proportions were calculated. Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) were used to assess multicollinearity of the independent variables. As all independent variables had VIF <2, they were included in the model. Logistic regression analysis was conducted to assess the relationship between treatment seeking practices and the independent variables. Independent variables which showed a significant association (p<0.05) on univariate regression were included in multivariate regression analysis. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratio with 95% confidence intervals are reported. The pattern of treatment seeking in patients belonging to households not generally seeking treatment from public health services according to reasons was assessed using Chi square test and odds ratio with 95% confidence intervals. In the survey, as certain states and categories of households were oversampled, household weights were used to restore the representativeness of the sample. The estimation of confidence intervals takes into account the effects of the complex sample design.

Ethical considerations

NFHS data are available for download through Demographic Health Survey (DHS) data distribution system. All DHS datasets are free to download and use after registration. The protocol for the NFHS-4 survey was approved by the IIPS Institutional Review Board and the ICF Institutional Review Board. Each respondent’s informed consent for participation in the survey was obtained. The results presented in this study are based on the analysis of existing survey data which do not contain patients’ name and other identifying information.

RESULTS

A total of 8696 self-reported TB cases were identified among 2,821,818 usual residents in the households covered during the survey [prevalence of self-reported TB: 308.17/100,000 population (95%CI:309.44–310.55/100,000 population)]. Table 1 describes the profile of the self-reported TB patients.

Table 1.

Profile of self-reported TB patients identified in NFHS − 4 (2015–16)

| Variables | Frequency N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (N=8696) | |

| 0–10 yrs | 287 (3) |

| 11–20 yrs | 559 (6) |

| 21–30 yrs | 1091 (13) |

| 31–40 yrs | 1307(15) |

| 41–50 yrs | 1539 (18) |

| 51–60 yrs | 1866 (22) |

| >60 yrs | 2047 (24) |

| Gender (N=8696) | |

| Female | 3112 (36) |

| Male | 5584 (64) |

| Education (N=8670) | |

| No education, Preschool | 4130 (47) |

| Primary | 1704(20) |

| Secondary | 2516(29) |

| Higher | 320 (4) |

| Wealth index (N=8696) | |

| Poor | 5016 (58) |

| Middle | 1610 (18) |

| Rich | 2070 (24) |

| Residence (N=8696) | |

| Rural | 6334 (73) |

| Urban | 2362(27) |

| Household structure (N=8696) | |

| Non-nuclear | 4661 (54) |

| Nuclear | 4035 (46) |

| Type of health service provider where household members generally go for treatment (N=8696) | |

| Other Health Services | 4537 (52) |

| Public Health services | 4159 (48) |

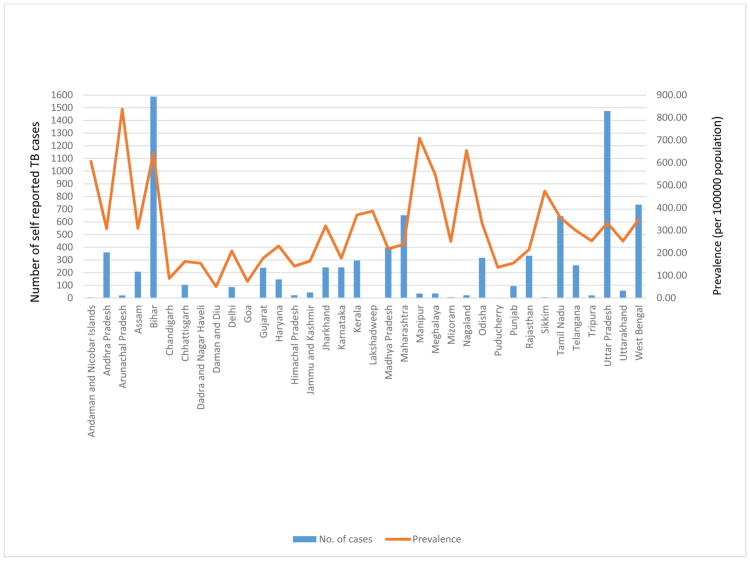

The prevalence of self-reported TB ranged from 50.46 to 837/100,000 population among the states and union territories. (Figure 1). The details of treatment sought was not reported for 21(0.24%) patients. 4757 [54.7% [95%CI: 53.1%–56.3%)] TB patients reported to be seeking treatment from the public sector and 566 [6.5 (95%CI: 6.5%–7.2%)] TB patients sought treatment from both public and private sector. 3352 [38.6% (95%CI: 36.5%–40.8%)] TB patients were outside care of public health services − 284 [3.3% (95%CI: 2.8%–3.9%)] patients not seeking any treatment and 3068 [35.3% (95%CI: 33.7%–36.9%)] patients accessing treatment from the private sector.

Figure 1.

State-wise number and prevalence of self-reported TB during NFHS-4 (2015–16)

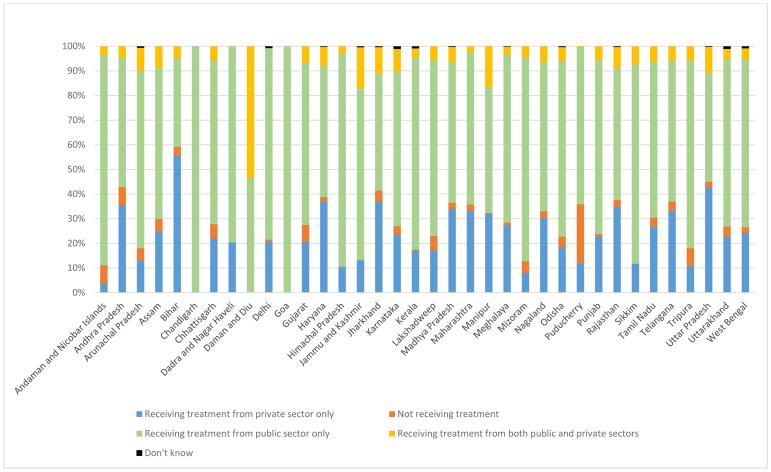

More than 40% of the patients with self-reported TB in Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand and Andhra Pradesh were outside coverage of treatment in public health services (Figure 2). There were two groups of tuberculosis patients who remained outside of the coverage of treatment under public health services. The first group was those patients who were not taking any treatment for TB and the other group was of TB patients accessing care from private health service providers. Patients who reported to be accessing treatment from ‘both public and private health services’ and patients accessing treatment from ‘public health services only’ were categorized as taking treatment from ‘public health services’ (N=5323).

Figure 2.

State-wise treatment accessed for self-reported TB - NFHS 4 (2015–16)

Table 2 compares the characteristics of patients who were not taking any treatment with those taking treatment from public health services. Unadjusted logistic regression found age, sex, education, wealth index and place where household members generally go for treatment to be significantly associated with not accessing TB treatment. Adjusted odds ratio shows that compared to patients in the age group 21 to 30 years, patients aged <10 years (OR=3.43;95%CI=1.52–7.77;p=0.00) and 31–40 years (OR=1.67,95%CI=1.05–2.65)] were more likely to not access TB treatment; patients with no/preschool education were 1.82 times (OR=1.82;95%CI=1.10–3.01;p=0.02) more at risk of not accessing TB treatment; those in the poorest wealth index (OR=1.86;95%CI=1.01–3.34;p=0.04) and patients from households which generally seek care from health care services other than public health services (OR=1.69;95%CI=1.26–2.26;p=0.00) were more likely to not seek TB treatment from public health services.

Table 2.

TB patients not accessing any treatment compared with patients accessing treatment from public health services in NFHS-4 (2015–16)

| Variables | TB treatment accessed from public health services | Univariate logistic regression | Multivariate logistic regression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No N=284 |

Yes N=5323 |

Total N=5607 |

P value | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

| Age | |||||||

| 0–10 yrs | 14 (10) | 124 (90) | 137(100) | 0.002 | 3.20 (1.51–6.81) | 0.003 | 3.43 (1.52–7.77) |

| 11–20 yrs | 11 (3) | 317 (97) | 328(100) | 0.89 | 1.06 (0.47–2.36) | 0.59 | 1.25 (0.56–2.79) |

| 21–30 yrs | 24 (3) | 705 (97) | 728(100) | Ref | Ref | ||

| 31–40 yrs | 48 (6) | 795 (94) | 843(100) | 0.02 | 1.77 (1.12–2.82) | 0.03 | 1.67 (1.05–2.65) |

| 41–50 yrs | 54 (5) | 944 (95) | 998(100) | 0.04 | 1.68 (1.01–2.81) | 0.14 | 1.50 (0.88–2.57) |

| 51–60 yrs | 58 (5) | 1183 (95) | 1241(100) | 0.14 | 1.44 (0.89–2.35) | 0.45 | 1.24 (0.70–2.19) |

| >60 yrs | 77 (6) | 1255 (94) | 1332(100) | 0.01 | 1.82 (1.15–2.87) | 0.07 | 1.59 (0.96–2.63) |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 116 (6) | 1778 (94) | 1894 (100) | 0.03 | 1.38 (1.04–1.84) | 0.15 | 1.24 (0.93–1.67) |

| Male | 168 (5) | 3545 (95) | 3713 (100) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Education | |||||||

| No education, Preschool | 189 (7) | 2506 (93) | 2695 (100) | 0.00 | 2.42 (1.57–3.69) | 0.02 | 1.82 (1.10–3.01) |

| Primary | 38 (3) | 1104 (97) | 1142 (100) | 0.75 | 1.10 (0.61–2.01) | 0.76 | 0.89 (0.45–1.79) |

| Secondary | 48 (3) | 1545 (97) | 1593 (100) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Higher | 8 (5) | 152 (95) | 160 (100) | 0.11 | 1.74 (0.88–3.44) | 0.08 | 2.01 (0.91–4.45) |

| Wealth index | |||||||

| Poor | 198 (6) | 3062 (97) | 3260 (100) | 0.009 | 2.0 (1.19–3.37) | 0.04 | 1.86 (1.01–3.34) |

| Middle | 47 (4) | 1071 (96) | 1118 (100) | 0.29 | 1.37 (0.76–2.44) | 0.32 | 1.38 (0.73–2.59) |

| Rich | 38 (3) | 1190 (97) | 1228 (100) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Residence | |||||||

| Rural | 215 (5) | 3846 (95) | 4061 (100) | 0.36 | 1.19 (0.82–1.72) | NA | NA |

| Urban | 69 (5) | 1477 (95) | 1546 (100) | Ref | |||

| Household structure | |||||||

| Nuclear | 146 (5) | 2549 (95) | 2695 (100) | 0.37 | 0.87 (0.65–1.17) | NA | NA |

| Non-nuclear | 138 (5) | 2774 (95) | 2912 (100) | Ref | |||

| Type of health service provider where household members generally go for treatment for other illnesses | |||||||

| Other Health Services | 150 (7) | 2079 (93) | 2229 (100) | 0.00 | 1.75 (1.31–2.33) | 0.00 | 1.69 (1.26–2.26) |

| Public Health services | 134 (4) | 3244 (96) | 3378 (100) | Ref | Ref | ||

Table 3 compares the characteristics of private TB patients to those of public sector patients. Unadjusted logistic regression shows age, gender, education, wealth index, household structure and place where household members generally go for treatment were significantly associated with type of health care provider. Adjusted regression analysis shows that compared to patients >60 years, children <10 years (OR=2.39; 95%CI=1.62–3.53; p=0.00) were two times more likely to seek treatment from private service providers. Female patients (OR=1.29; 95%CI=1.11–1.50; p=0.001) and those with secondary (OR=1.22; 95%CI=1.02–1.48; p=0.03) and higher education (OR=1.82; 95%CI=1.11–2.98; p=0.02) were more likely to seek treatment from private providers. Patients from households which generally reported to seek care from providers other than public health services were 4.6 times more likely (OR=4.56;95%CI=3.95–5.27;p=0.00) to seek TB care from private providers.

Table 3.

Type of health service providers from whom TB treatment was being accessed in NFHS-4 (2015–16)

| Variables | Type of health service providers | Univariate logistic regression | Multivariate logistic regression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private Health Services N=3068 |

Public health Services N=5323 |

Total N=8391 |

P value | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

| Age | |||||||

| 0–10 yrs | 149 (55) | 124 (45) | 273 (100) | 0.00 | 2.13 (1.48–3.05) | 0.00 | 2.39 (1.62–3.53) |

| 11–20 yrs | 230 (42) | 316 (58) | 546 (100) | 0.06 | 1.29 (0.99–1.69) | 0.28 | 1.19 (0.87–1.61) |

| 21–30 yrs | 360 (34) | 704 (66) | 1064 (100) | 0.43 | 0.91 (0.71–1.16) | 0.08 | 0.78 (0.59–1.03) |

| 31–40 yrs | 463 (37) | 795 (66) | 1258 (100) | 0.76 | 1.03 (0.85–1.26) | 0.57 | 1.07 (0.85–1.33) |

| 41–50 yrs | 533 (36) | 944 (64) | 1477 (100) | 0.99 | 1.00 (0.81–1.23) | 0.61 | 1.06 (0.84–1.34) |

| 51–60 yrs | 625 (34) | 1184 (66) | 1808 (100) | 0.47 | 0.94 (0.78–1.12) | 0.65 | 0.95 (0.78–1.17) |

| >60 yrs | 708 (36) | 1125 (64) | 1963 (100) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 1210 (40) | 1778 (60) | 2988 (100) | 0.00 | 1.30 (1.14–1.48) | 0.001 | 1.29 (1.11–1.50) |

| Male | 1858 (34) | 3545 (66) | 5403 (100) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Education | |||||||

| No education, Preschool | 1423 (36) | 2506 (64) | 3929 (100) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Primary | 562 (34) | 1104 (66) | 1666 (100) | 0.77 | 0.89 (0.77–1.05) | 0.89 | 1.01 (0.84–1.22) |

| Secondary | 916 (37) | 1545 (63) | 2461 (100) | 0.59 | 1.05 (0.89–1.23) | 0.03 | 1.22 (1.02–1.48) |

| Higher | 160 (51) | 152 (49) | 312 (100) | 0.001 | 1.86 (1.27–2.72) | 0.02 | 1.82 (1.11–2.98) |

| Wealth index | |||||||

| Poor | 1743 (36) | 3062 (64) | 4804 (100) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Middle | 490 (31) | 1071 (69) | 1561 (100) | 0.01 | 0.80 (0.68–0.96) | 0.09 | 0.85 (0.69–1.03) |

| Rich | 361 (46) | 422 (54) | 745 (100) | 0.02 | 1.23 (1.03–1.47) | 0.63 | 1.05 (0.85–1.30) |

| Residence | |||||||

| Rural | 2558 (37) | 3846 (63) | 6104 (100) | 0.47 | 1.07 (0.89–1.29) | NA | NA |

| Urban | 810 (35) | 1477 (65) | 2287 (100) | Ref | |||

| Household structure | |||||||

| Non-nuclear | 1738 (38) | 2774 (62) | 4512 (100) | 0.007 | 1.20 (1.05–1.37) | 0.09 | 1.14 (0.98–1.32) |

| Nuclear | 1330 (34) | 2549 (66) | 3879 (100) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Type of health service provider where household members generally go for treatment for other illnesses | |||||||

| Other Health Services | 2295 (52) | 2079 (48) | 4374 (100) | 0.00 | 4.63 (3.99–5.38) | 0.00 | 4.56 (3.95–5.27) |

| Public Health services | 773 (19) | 3244 (81) | 4017 (100) | Ref | Ref | ||

A total of 4524 TB patients belonged to households not generally accessing treatment from public health services for other illnesses. Table 4 describes the pattern of treatment-seeking according to reasons for generally not accessing treatment from public health services among these patients. The reasons ‘no nearby facility’ and ‘poor quality of care’ showed significant association with TB treatment seeking practices. Patients from households reporting ‘no nearby facility’ as a reason for not generally seeking treatment from public health services were 1.37 times (OR=1.37; 95% CI=1.21–1.54;p=0.00) more likely to seek TB treatment from public health services than patients from households not reporting this reason. Patients from households reporting ‘poor quality of care’ as a reason for not generally seeking treatment from public health services were 1.44 times (OR=1.45; 95% CI=1.28–1.63;p=0.00) more likely to remain outside the coverage of TB treatment in public health services. The other reasons did not show any significant association with the TB treatment seeking practices.

Table 4.

Pattern of treatment seeking among TB patients belonging to households which generally do not seek treatment from public health services for other illnesses

| Reasons for generally not seeking treatment from public health services for other illness | Treatment seeking for TB | Chi square; p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not seeking any treatment n=150 N (%) |

Seeking treatment from public/public and private health services n=2079 N (%) |

Seeking treatment from private health services only n=2295 N (%) |

Total n=4524 N (%) |

||

| No nearby facility | |||||

| Yes | 76 (4) | 1000 (50) | 912 (46) | 1988 (100) | 33.81; 0.00 |

| No | 74 (3) | 1079 (43) | 1383 (54) | 2536 (100) | |

| Facility timing not convenient | |||||

| Yes | 48 (4) | 613 (45) | 689 (51) | 1350 (100) | 0.49; 0.78 |

| No | 102 (3) | 1466 (46) | 1606 (51) | 3174 (100) | |

| Health personnel often absent | |||||

| Yes | 23 (3) | 354 (48) | 364 (49) | 741 (100) | 1.21; 0.55 |

| No | 127 (3) | 1725 (46) | 1931 (51) | 3783 (100) | |

| Waiting time too long | |||||

| Yes | 65 (4) | 794 (44) | 928 (52) | 1787 (100) | 3.25; 0.20 |

| No | 85 (3) | 1285 (47) | 1367 (50) | 2737 (100) | |

| Poor quality of care | |||||

| Yes | 76 (3) | 1026 (42) | 1355 (55) | 2457 (100) | 42.11; 0.00 |

| No | 74 (4) | 1053 (51) | 940 (45) | 2067 (100) | |

| Other reasons | |||||

| Yes | 2 (1) | 104 (49) | 106 (50) | 212 (100) | 4.26; 0.12 |

| No | 148 (3) | 1975 (46) | 2189 (51) | 4312 (100) | |

DISCUSSION

In this analysis of NFHS data, 39% of the TB patients were outside the coverage of treatment under public health services with 35% reported to be taking care from the private sector. However, of the total 1,754,957 cases notified under RNTCP in the year 2016, only 19% were notified from private sector [13]. Our results suggest that there may be a large underestimate of TB cases who are never notified by the private health sector. The prevalence of TB in this study was 316/100,000 population. Other studies and reports have reported a prevalence rate of TB ranging from 195 to 390 cases per 100,000 population [3, 14, 15]. Comparing these prevalence rates and the current notification rates of 135 cases/100,000 [13], it is estimated that nearly 34% of the estimated cases i.e. nearly a million TB patients may be outside the care under RNTCP. This extrapolation matches with our estimates of 35% TB patients who remain outside TB care in public health services and other estimates of under-reported TB cases based on pharmacy sales [5], and strengthens the evidence that surveillance efforts must expand in order to accurately reflect TB disease burden. RNTCP is scheduled to release results of a nationwide TB prevalence survey in 2018/2019, which may define the current burden more accurately

TB patients reported to be not accessing any treatment (3%) are patients who could have been diagnosed in the public/private sector but were not accessing any treatment during the survey. These patients can be classified as initial defaulters/pretreatment lost-to-follow-up or treatment defaulters. The proportion of initial default ranges from 4% to 38% [16–19]. Initial defaulters are infectious and experience high morbidity and mortality [20,21]. Treatment default for new and previously treated TB patients under RNTCP is 5% and 11% respectively [13]. There could be an underestimation of this group in our study due to social desirability bias in which respondents may have not reported about TB patients not taking any treatment. In our study, factors significantly associated with this group were patient’s age, educational status, wealth index and type of health services from where treatment was sought for other illnesses. Other studies too have reported age, illiteracy, and poor socioeconomic status as risk factors for default [16, 22–25]. There is a need to focus on this high risk group with enhanced counselling and follow up services to retain them in the treatment network.

Younger age, female gender and higher education were significantly associated with accessing treatment from private health sector. These groups of patients are likely to be under-reported in the surveillance system under RNTCP. In a study from Kerala in which women were less likely to participate in Directly Observed Treatment (DOT), social stigma was identified to be the most common reason for non-participation among women, indicating the program’s perceived lack of confidentiality and fear of social stigma and rejection [26]. Of note, parents of children were more than twice as likely to seek care outside of the public health services. Diagnosing childhood TB is difficult and studies have shown that health-seeking behavior and associated delays can impact treatment initiation [27]. A recent study in Delhi described an association between first provider and number of providers seen with regard to the health system delay in seeking care for childhood tuberculosis [28]. Specific interventions aimed at encouraging adults to bring their children in to the RNTCP for care may help to close the gap.

There was no significant association between wealth index and type of health service provider for TB treatment with 46% of the patients in richest wealth index and 36 % of patients in lower wealth indices seeking care from the private sector. This entails out-of-pocket expenditure for TB patients irrespective of their socioeconomic status.

The strongest statistically significant finding of our study, the odds of seeking treatment outside of the public health services being four times as high for households generally seeking care in the private sector, indicates that this population is following a pattern of care-seeking behavior. Care-seeking behavior is notoriously complex, and changing it will require strategic efforts for streamlining patients into the national program.

The pattern of treatment seeking for TB according to the reasons for not generally accessing treatment from public health services is interesting. A significant proportion of patients from households which perceived ‘ no nearby facility’ to be a reason for not accessing treatment from government health facility for other illnesses were accessing treatment for TB from public health services. This highlights the success of the RNTCP strategy in which DOT services are provided near patients’ residence ensuring proximity and convenience [29]. Patients from households reporting poor quality of services to be the reason for not utilizing government health facilities were more likely to remain outside the coverage of TB treatment in public health services. In a study among TB patients attending a private hospital in Mumbai, 68% reported reservations about the quality of health care in government hospitals, general lack of trust in government services, lack of attention, long waits, poor hygiene and suspect quality of drugs [30]. Our analysis shows that the decentralized DOTS services have been successful in overcoming barriers such as distance, non-availability of health personnel and waiting time related to public health services but the perception of poor quality of care continues to be a major barrier for improving the coverage of treatment for TB under public health services.

TB patients switch from one health service provider to another during the course of treatment [31, 32]. Though this aspect was not captured in this cross-sectional survey, 7% of the TB patients were found to be accessing care from both private and public health services. Studies need to be conducted to understand the reasons for accessing treatment from multiple health care providers.

The data about the diagnosis of TB and the treatment seeking were collected during the household survey without cross-checking of source documentation from the public/private sector. During the NFHS-4 survey any adult member of the household served as the respondent. This suggests that during NFHS-4, TB data would have been reported only if the respondent was aware of the TB case in the household and willing to identify a TB case. As other details of treatment were not asked during the survey, the study could not identify if any patients who were taking care from the private health sector were enrolled for DOTS under public private partnership initiative of RNTCP [33]. These factors can cause an underestimation of TB prevalence and misclassification of type of health service providers from whom TB treatment was being sought.

Despite these limitations, the study provides insights toward the intense efforts that will be required to involve the private health sector in accurate surveillance and linking patient groups requiring targeted interventions to the national program.

Conclusion

Enhanced counselling and follow-up services for patients with low socio-economic status who are at high risk of default will ensure their retention in the treatment network. Considering the large proportion of TB patients being managed in the private sector, it is imperative that the public-private initiative under RNTCP is strengthened along with the notification and surveillance systems. Improving the quality of public health services in general along with their perception in the community and ensuring patient confidentiality will help improve the coverage of TB treatment in public health services.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Geeta Pardeshi and Andrea Deluca were supported by the BJGMC JHU HIV TB Program funded by the Fogarty International Center, NIH (D43TW009574). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report - 2017. Geneva: 2017. (Available from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/259366/1/9789241565516-eng.pdf?ua=1) [10 November 2017] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. A brief history of tuberculosis control in India. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Satyanarayana S, Nair SA, Chadha SS, et al. From Where Are Tuberculosis Patients Accessing Treatment in India? Results from a Cross-Sectional Community Based Survey of 30 Districts. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hazarika I. Role of Private Sector in Providing Tuberculosis Care: Evidence from a Population-based Survey in India. J Glob Infect Dis. 2011;3(1):19–24. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.77291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arinaminpathy N, Batra D, Khaparde S, et al. The number of privately treated tuberculosis cases in India: an estimation from drug sales data. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(11):1255–1260. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30259-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anand T, Babu R, Jacob AG, Sagili K, Chadha SS. Enhancing the role of private practitioners in tuberculosis prevention and care activities in India. Lung India. 2017;34(6):538–544. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.217577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satyanarayana S, Subbaraman R, Shete P, et al. Quality of tuberculosis care in India: a systematic review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19(7):751–63. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.15.0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murrison LB, Ananthakrishnan R, Sukumar S, et al. How Do Urban Indian Private Practitioners Diagnose and Treat Tuberculosis? A Cross-Sectional Study in Chennai. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0149862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Satyanarayana S, Kwan A, Daniels B, et al. Use of standardised patients to assess antibiotic dispensing for tuberculosis by pharmacies in urban India: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(11):1261–1268. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30215-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das J, Kwan A, Daniels B, et al. Use of standardized patients to assess quality of tuberculosis care: a pilot, cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(11):1305–1313. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00077-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The DHS Program, India. [accessed on 2 Jan 2018];Standard DHS,-2015–16. from (Available from https://dhsprogram.com/data/dataset/India_Standard-DHS_2015.cfm?flag=0) [2 January 2018]

- 12.International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015–16: India. Mumbai: IIPS; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Central TB Division. RNTCP Annual status report, 2017 Directorate General of Health Services Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Govt of India; Mar, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report. Geneva: 2016. (Available from http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s23098en/s23098en.pdf) [11 November 2017] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report. Geneva: 2015. (Available from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/191102/1/9789241565059_eng.pdf) [11 November 2017] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sai Babu B, Satyanarayana AV, Venkateshwaralu G, et al. Initial default among diagnosed sputum smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Andhra Pradesh, India. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12(9):1055–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehra D, Kaushik RM, Kaushik R, Rawat J, Kakkar R. Initial default among sputum-positive pulmonary TB patients at a referral hospital in Uttarakhand, India. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2013;107(9):558–65. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trt065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacPherson P, Houben RMGJ, Glynn JR, Corbett EL, Kranzer K. Pre-treatment loss to follow-up in tuberculosis patients in low- and lower-middle-income countries and high-burden countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2014;92:126–138. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.124800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jayabal L, Frederick A, Mehendale S, Banurekha V. Indicators to Ensure Treatment Initiation of All Diagnosed Sputum Positive Pulmonary Tuberculosis Patients under Tuberculosis Control Programme in India. Indian J Community Med. 2017 Oct-Dec;42(4):238–241. doi: 10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_361_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Squire SB, Belaye AK, Kashoti A, et al. ‘Lost’ smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis cases: where are they and why did we lose them? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9:25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tiemersma EW, van der Werf MJ, Borgdorff MW, Williams BG, Nagelkerke NJ. Natural history of tuberculosis: duration and fatality of untreated pulmonary tuberculosis in HIV negative patients: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saibannavar A, Desai S. Risk factors associated with default among smear positive TB patients under RNTCP in western Maharashtra. OSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences. 2016;15( 3):50–56. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Babiarz KS, Suen S, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD. Tuberculosis treatment discontinuation and symptom persistence: an observational study of Bihar, India’s public care system covering >100,000,000 inhabitants. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:418. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vijay S, Kumar P, Chauhan LS, Vollepore BH, Kizhakkethil UP, Rao SG. Risk Factors Associated with Default among New Smear Positive TB Patients Treated Under DOTS in India. PLoS One. 2010 Apr 6;5(4):e10043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asati A, Nayak S, Indurkar M. A study on Factors associated with non-adherence to ATT among pulmonary tuberculosis patients under RNTCP. International Journal of Medical Science and Clinical Inventions. 2017;4(3):2759–2763. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balasubramanian VN, Oommen K, Samuel R. DOT or not? Direct observation of anti-tuberculosis treatment and patient outcomes, Kerala State, India. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000;4(5):409–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sullivan BJ, Esmaili BE, Cunningham CK. Barriers to initiating tuberculosis treatment in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review focused on children and youth. Global Health Action. 2017;10:1, 1290317. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1290317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalra A. Care seeking and treatment related delay among childhood tuberculosis patients in Delhi, India. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2017;21(6):645–650. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.16.0563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nirupa C, Sudha G, Santha T, et al. Evaluation of directly observed treatment providers in the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme. Indian J Tuberc. 2005;52:73–77. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pinto LM, Udwadia ZF. Private patient perceptions about a public programme; what do private Indian tuberculosis patients really feel about directly observed treatment? BMC Public Health. 2010;10:357. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mistry N, Rangan S, Dholakia Y, Lobo E, Shah S, Patil A. Durations and Delays in Care Seeking, Diagnosis and Treatment Initiation in Uncomplicated Pulmonary Tuberculosis Patients in Mumbai, India. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0152287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yellappa V, Lefèvre P, Battaglioli T, Devadasan N, Van der Stuyft P. Patients pathways to tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment in a fragmented health system: a qualitative study from a south Indian district. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:635. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4627-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Central TB Division. Directorate of Health Services National Guidelines for partnership Revised National Tuberculosis Program Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Govt. of India; 2014. [Google Scholar]