Abstract

Background

In Thailand, pharmaceutical care has been recently introduced to a tertiary hospital as an approach to improve adherence to tuberculosis (TB) treatment in addition to home visit and modified directly observed therapy (DOT). However, the economic impact of pharmaceutical care is not known.

Objective

The aim of this study was to estimate healthcare resource uses and costs associated with pharmaceutical care compared with home visit and modified DOT in pulmonary TB patients in Thailand from a healthcare sector perspective inclusive of out-of-pocket expenditures.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study using data abstracted from the hospital billing database associated with pulmonary TB patients who began treatment between 2010 and 2013 in three hospitals in Thailand. We used generalized linear models to compare the costs by accounting for baseline characteristics. All costs were converted to international dollars (Intl$)

Results

The mean direct healthcare costs to the public payer were $519.96 (95%confidence interval [CI] 437.31–625.58) associated with pharmaceutical care, $1020.39 (95% CI 911.13–1154.11) for home visit, and $887.79 (95% CI 824.28–955.91) for modified DOT. The mean costs to patients were $175.45 (95% CI 130.26–230.48) for those receiving pharmaceutical care, $53.77 (95% CI 33.25–79.44) for home visit, and $49.33 (95% CI 34.03–69.30) for modified DOT. After adjustment for baseline characteristics, pharmaceutical care was associated with lower total direct costs compared with home visit (−$354.95; 95% CI −285.67 to −424.23) and modified DOT (−$264.61; 95% CI −198.76 to −330.46).

Conclusion

After adjustment for baseline characteristics, pharmaceutical care was associated with lower direct costs compared with home visit and modified DOT.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s41669-017-0053-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| In Thailand, pharmaceutical care is a more recent and relatively simple approach to improve adherence to pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) treatment compared with home visit and modified directly observed therapy (DOT). |

| Our findings shed light on the potential role of the clinical pharmacist in pulmonary TB outpatient services. Timely pharmacist-led patient education for every outpatient visit and pharmacist-provided telephone consultation required less healthcare resources. |

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Thailand is one of the 22 high-burden countries for tuberculosis (TB) with nearly 160,000 TB patients, and 11,900 TB-related deaths in 2014 [1]. In 2014, the domestic funding for the Thai National TB program exceeded the contributions from international donors, with only 11% of the budget funded internationally [1]. Most TB patients seek healthcare in public hospitals where TB diagnosis and treatment are covered by Thai public insurance schemes. Healthcare for people with TB-related symptoms usually starts with initial clinical consultation, diagnostic tests, and non-TB specific medications [2, 3]. The TB diagnostic process may require multiple visits to complete the tests and meet healthcare professionals for medical diagnosis [4, 5]. Before TB diagnosis and during TB treatment, healthcare may include hospitalization, treatment of adverse drug reactions (ADRs), and augmenting nutrition.

Although WHO recommends directly observed therapy (DOT) to promote adherence for pulmonary TB patients [6], it is not feasible to widely implement DOT for TB control in Thailand, especially in the large hospitals due to healthcare resource constraints. Therefore, the national TB program adopts a daily dose regimen whereby patients take the TB medications themselves at home and visit a health center or a district hospital at least once a month to refill their prescriptions. Hospitals adopt different supervision approaches, including home visit and modified DOT (see below for details). Recently, pharmaceutical care, a pharmacist-led patient education program, was adopted in a tertiary hospital to improve adherence to TB treatment.

According to our previous retrospective cohort study [7], all three TB treatment adherence enhancement strategies that are currently adopted in Thai referral hospitals provided very similar TB treatment success rates and were associated with high rates of success and exceeded the WHO treatment success target of 85%. However, there is little evidence on the economic implications associated with these strategies. Healthcare resource uses and costs have been recognized as important pieces of information to inform health policy making, especially in allocating public funds in resource-constrained contexts. Therefore, this study is a cost-minimization analysis, from a healthcare sector perspective, inclusive of out-of-pocket expenditures. The objective of this study is to estimate and compare direct costs associated with pharmaceutical care compared with home visit and modified DOT in pulmonary TB patients in Thailand.

Methods

Data Sources

This was a retrospective study based on patient medical records, TB registration records, and the billing database at three public referral hospitals in Songkhla province, southern Thailand: Songklanagarind hospital, Hatyai hospital, and Songkhla hospital, where pharmaceutical care, home visit, and modified DOT, respectively, have been adopted. Songklanagarind hospital is an 850-bed teaching hospital affiliated to the Prince of Songkla University (PSU). Hatyai hospital (700-bed, tertiary care) and Songkhla hospital (480-bed, secondary care) are the main provincial referral hospitals under the Ministry of Public Health. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at each of the participating hospitals.

Pharmaceutical care provides pharmacist-led patient education at every outpatient visit and telephone consultation at any time via mobile phone regarding disease, medications, possible ADRs, and lifestyle modifications. The home visit approach provides regular home visit until treatment completion. The modified DOT provides direct observation, but only for the first 2 weeks of TB treatment, followed by regular home visit. The description of each of these TB treatment adherence enhancement strategies is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of each treatment strategy

| Services | Pharmaceutical care | Home visit | Modified DOT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outpatient visits | |||

| Who provides the services? | Clinical pharmacist | Nurse | Nurse or pharmacist |

| Activities | Pharmacist-led patient education Monitoring and management of ADRs Identifying other drug-related problems Evaluation of treatment adherence Providing pharmacist’s telephone consultation |

Nurse-led patient education Monitoring and management of ADRs Evaluation treatment adherence |

Nurse- or pharmacist-led patient education Monitoring and management of ADRs Evaluation of treatment adherence |

| Follow-up frequencya | Days 0, 14, 60, 120, 180 or Days 0, 14, 60, 90 or 120, 150, 180 |

Days 0, 14, (30), 60, 90, (120), 150, 180 | Days 0, 30, 60, 90, 150, 180 |

| Supervision activities | |||

| Who provides the services? | None | Non-medical staff | Non-medical staff |

| Activities | None | Home visit Patients take medications by themselves at home with regular home visit |

DOT Patients take medications under direct supervision Home visit Patients take medications by themselves at home with regular home visit |

| Visit schedule | None | Home visit Once a week in the first 2 months Once a month until treatment completion |

Daily DOT First 2 weeks of treatment Home visit Twice a week for the first month Once a week in the second month Twice a month until treatment completion |

ADRs adverse drug reactions, DOT directly observed therapy

a The outpatient follow-up frequency depends on patient’s individual condition and the occurrence of ADRs

Patient Eligibility Criteria

The eligibility criteria for this cost analysis included age ≥18 years, pulmonary TB confirmed by a physician and classified bacteriologically as smear-positive or smear-negative, TB treatment started between October 2010 and September 2013, and a treatment period of ≥2 months in the study hospitals.

Recommended TB Treatment in Thailand

First-line anti-TB medications include isoniazid (H), rifampicin (R), pyrazinamide (Z), ethambutol (E), and streptomycin (S). The standard treatment regimen for drug-susceptible pulmonary TB is a daily combination of four first-line antibiotics (2HRZE/4HR) for at least 6 months divided into two treatment phases: an intensive phase (first 2 months) and a continuous phase (the remaining 4 months). Re-treatment patients are treated with an 8-month re-treatment regimen (2HRZES/1HRZE/5HRE), while patients with multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) require second-line agents (at least 20 months) as recommended by WHO [1].

Healthcare Resource Uses and Costs

The cost analysis was conducted from a healthcare sector perspective inclusive of out-of-pocket expenditures, which included direct healthcare costs to the public payer and to the patients. Costs were estimated separately for the pre-TB treatment period (from illness onset to TB diagnosis) and the TB treatment period (from the start to the completion of TB treatment). These costs were considered as costs associated with TB diagnosis and treatment if patients were diagnosed with at least one of the two ICD-10 codes for respiratory TB (A15 or A16). There are a few other relevant healthcare resource uses (e.g., treatment of ADRs, hospitalization, nutrition, and others). Therefore, costs incurred with some ICD-10 codes needed to be investigated concurrently with other information (e.g., type of outpatient service, laboratory investigation, patient’s medical record, and TB registration record) before they were determined to be associated with TB diagnosis and treatment (see Appendix Table 1 in the electronic supplementary material).

The Thai population has been covered under one of the three public insurance schemes: the civil servant medical benefits scheme (CSMBS), the social security scheme (SSS), and the universal coverage scheme (UC), all funded through general tax revenues [8]. The CSMBS covers government employees, pensioners, and their dependents in which insured persons can access, free of charge, medical services at all government hospitals. The SSS is for private employees who can freely access medical services at a contracted hospital. Every Thai citizen not covered under the CSMBS or the SSS is covered by the UC, but needs to pay all medical costs out of pocket if they seek healthcare services outside their primary residential area. As of 2015, 75% of the Thai population is covered under the UC [9].

Following the Thai Comptroller General’s Department’s healthcare service classification, we categorized direct costs into seven categories: medications, laboratory investigation and pathology, diagnostic radiology, medical services, supervision activities, hospitalization, and miscellaneous costs. Except medications costs, which were calculated using a mark-up method, unit costs of services in all remaining categories were set by factoring the costs related to labor, material, capital, overhead, and future development costs. Direct costs for each healthcare service in the hospitals were calculated by multiplying the natural units for the services with the corresponding unit costs. Costs associated with implementing supervision activities (i.e., the home visit at Hatyai hospital and the modified DOT at Songkhla hospital) were estimated separately as non-medical staff must be hired to provide these services. In addition to the salary paid from hospital, the global fund paid these staff 600 baht for each smear-positive drug-susceptible patient who successfully completed treatment, and 300 baht monthly for supervising each MDR-TB patient.

Methods for handling missing information varied depended on the type of data. Missing resource use items for laboratory investigation and diagnostic radiology were replaced by using each hospital’s standard procedures for pulmonary TB care, while missing quantities of medication used were estimated from patients’ drug regimen.

Out-of-pocket expenditures not covered by patients’ health insurance were also retrieved from hospital billing databases. These costs included copayment, non-essential drugs (NEDs), food nutrition, and non-covered medical costs (e.g., costs incurred to patients when accessing services provided outside their district).

All costs were calculated in Thai currency (Thai baht), adjusted with the cumulative inflation rate from the year of data collection to 2015 [10], and then converted to international dollars using the 2015 purchasing power parity (PPP) conversion factor of private consumption (LCU per international $) [11].

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses of demographic data were conducted to describe the patient population included in the cost analyses. Categorical variables were analyzed using a Chi squared test, unless expected cell counts were low, in which case Fisher’s exact test was used. Mean and standard deviation (SD) was calculated for continuous variables and differences were evaluated using analysis of variance (ANOVA).

For the cost data, measures other than the arithmetic mean (e.g., median costs, log transformed costs) do not provide information about the costs of treating all patients, which is more informative for healthcare policy decisions [12]. Therefore, we reported arithmetic mean costs with SD. Since the Shapiro–Wilk test indicated that all costs data were positively skewed, a nonparametric bootstrap technique was used to compare arithmetic mean costs and to derive the 95% confidence intervals (CI) [13].

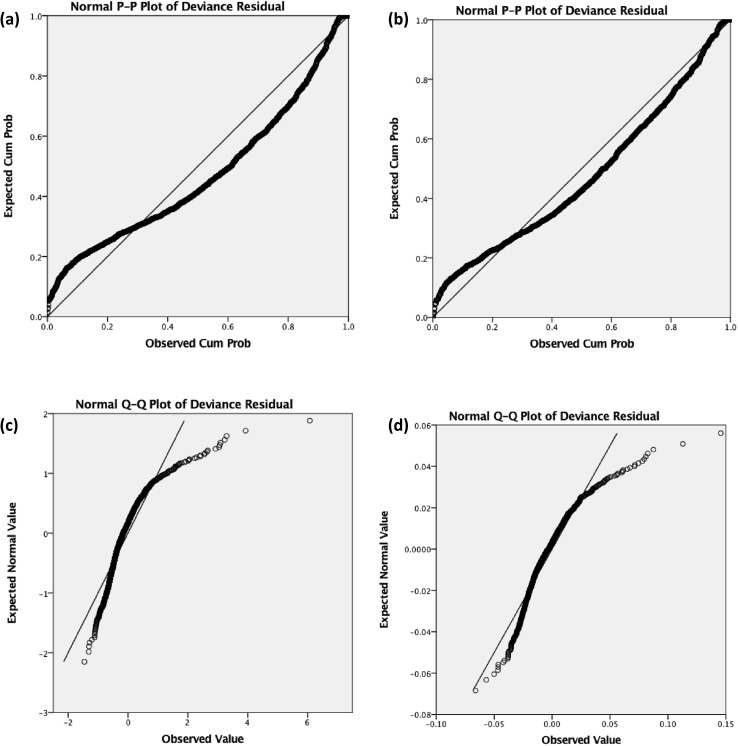

Differences in the total costs between treatment strategies adjusted for baseline demographics were investigated by generalized linear models (GLMs) [14, 15]. The performance of GLMs with the inverse Gaussian and gamma distribution were investigated. Two different link functions (e.g., the identity and log link) were compared. Covariates act additively in the identity-link model, and multiplicatively in the log-link model [14]. Thus, GLMs using an identity link estimate the difference in costs, while those using a log link estimate a ratio. The model included six baseline covariates of treatment strategy, sex, age, habitat, health insurance, and HIV status. Model performance was assessed by using normal probability plots (P–P plots), normal quantile plots (Q–Q plots) of deviance residuals [14, 16], and Akaike information criterion (AIC) [14, 17]. Smaller AIC values indicate better-fitting models; differences of ten or more in AIC indicate that the better-fitting model should be strongly preferred [14]. Normal plots were assessed visually. When points fall close to the reference line this indicates that model assumptions are suitable [14, 16, 18]. Data analyses were performed using SPSS software [19].

Results

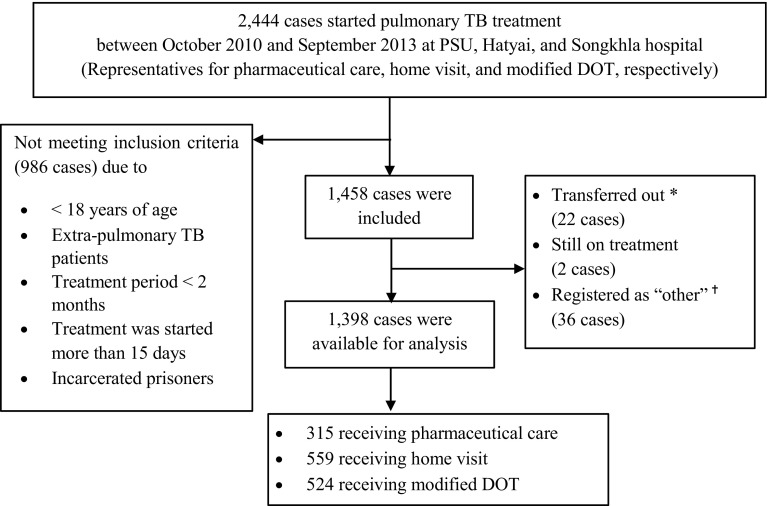

Between October 2010 and September 2013, 2444 adult patients started pulmonary TB treatment in the three study hospitals and 1398 patients met our eligibility criteria and were included in the analysis. There were 315 patients on pharmaceutical care, 559 on home visit, and 524 on modified DOT (Fig. 1). Baseline characteristics and complications in TB treatment of the included patients are described in Table 2.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study participants. Asterisk indicates ‘Transferred out’ are patients who have started the TB treatment, then relocated to new address. Therefore, they were transferred to new district. Transferred patients for whom the treatment outcome was unknown were excluded. Dagger indicates patients were categorized as ‘other’ by using the available medical record and their provided information. ‘Other cases’ are all cases that do not fit the definitions of ‘new’, ‘previously treated’ (e.g., relapse, treatment after failure, treatment after default), and ‘transfer in’, such as patients for whom it is not known whether they have been previously treated; who were previously treated but with unknown treatment outcome; who have returned to treatment with smear-negative pulmonary TB or bacteriologically negative extrapulmonary TB. DOT directly observed therapy, PSU Prince of Songkla University, TB tuberculosis

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics and complications in tuberculosis treatment of 1398 participants categorized by treatment strategy

| Variables | 1398 cases | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical care (n = 315) n (%) |

Home visit (n = 559) n (%) |

Modified DOT (n = 524) n (%) |

||

| Baseline characteristics | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 192 (61.0) | 388 (69.4) | 342 (65.3) | 0.037 |

| Female | 123 (39.0) | 171 (30.6) | 182 (34.7) | |

| Mean age (SD), years | 49.90 (18.42) | 44.85 (15.83) | 45.38 (16.56) | <0.001a |

| Age group, years | ||||

| 18–24 | 34 (10.8) | 52 (9.3) | 44 (8.4) | <0.001 |

| 25–34 | 46 (14.6) | 114 (20.4) | 110 (21.0) | |

| 35–44 | 39 (12.4) | 129 (23.1) | 127 (24.2) | |

| 45–54 | 66 (21.0) | 117 (20.9) | 96 (18.3) | |

| ≥55 | 130 (41.3) | 147 (26.3) | 147 (28.1) | |

| Live in Songkhla | ||||

| Yes | 178 (56.5) | 559 (100) | 524 (100) | <0.001 |

| No | 137 (43.5) | 0 | 0 | |

| Health insuranceb | ||||

| UC | 95 (30.2) | 375 (67.1) | 352 (67.2) | <0.001 |

| CSMBS | 132 (41.9) | 32 (5.7) | 61 (11.6) | |

| SSS | 12 (3.8) | 113 (20.2) | 92 (17.6) | |

| Not covered by public health insurance | 76 (24.1) | 39 (7.0) | 19 (3.6) | |

| HIV status | ||||

| Yes | 10 (3.2) | 99 (17.7) | 100 (19.0) | <0.001 |

| No | 256 (81.3) | 445 (79.6) | 420 (80.2) | |

| Unknown | 49 (15.6) | 15 (2.7) | 4 (0.8) | |

| Co-morbidity | ||||

| Yes | 157 (49.8) | 154 (27.5) | 140 (26.7) | <0.001 |

| No | 158 (50.2) | 405 (72.5) | 384 (73.3) | |

| Sputum smear | ||||

| Positive | 271 (86.0) | 455 (79.6) | 348 (66.4) | <0.001 |

| Negative | 44 (14.0) | 114 (20.4) | 176 (33.6) | |

| Registration | ||||

| New | 288 (91.4) | 539 (96.4) | 473 (90.3) | <0.001 |

| Re-treatment | 27 (8.6) | 20 (3.6) | 51 (9.7) | |

| Complications in TB treatment | ||||

| Develop MDR-TB | ||||

| Yes | 5 (1.6) | 2 (0.0 4) | 1 (0.2) | 0.019c |

| No | 308 (97.8) | 557 (99.6) | 522 (99.6) | |

| MDR-TB at baseline | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 1 (0.02) | |

| Re-challenge anti-TB drug use | ||||

| Yes | 27 (8.6) | 63 (11.3) | 43 (8.2) | 0.186 |

| No | 288 (91.4) | 496 (88.7) | 481 (91.8) | |

| Hepatotoxicity with anti-TB drugs | ||||

| Yes | 19 (6.0) | 40 (7.2) | 26 (5.0) | 0.320 |

| No | 396 (94.0) | 519 (92.8) | 498 (95.0) | |

| Adverse events | ||||

| No adverse events | 146 (46.3) | 389 (69.6) | 429 (81.9) | <0.001 |

| Severe | 28 (8.9) | 63 (11.3) | 45 (8.6) | |

| Mild | 141 (44.8) | 107 (19.1) | 50 (9.5) | |

| Hospitalization for TB | ||||

| Yes | 7 (2.2) | 127 (22.7) | 145 (27.7) | <0.001 |

| No | 308 (97.8) | 432 (77.3) | 379 (72.3) | |

Variables were analyzed using Chi squared test, unless expected cell counts were low, in which case Fisher’s exact test was used

ANOVA analysis of variance, DOT directly observed therapy, MDR-TB multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis, TB tuberculosis

a One-way ANOVA

b Thai population have been covered under one of the three public insurance schemes, namely the civil servant medical benefits scheme (CSMBS), the social security scheme (SSS), and the universal coverage (UC)

c Fisher’s Exact test

Forty-three percent of patients in the pharmaceutical care group traveled from a neighboring province to seek TB care at the study hospital, while all patients in the home visit and the modified DOT groups lived in Songkhla province. Sixty-seven percent of patients each in the home visit and the modified DOT groups were covered by the UC, compared with only 30.2% in the pharmaceutical care group. The pharmaceutical care group had more patients who accessed healthcare that was not covered by their public insurance (24.1, 7.0, and 3.6% for patients receiving pharmaceutical care, home visit, and modified DOT, respectively). Only 2% of patients in the pharmaceutical care group were hospitalized, while 22.7 and 27.7% were hospitalized in home visit and modified DOT groups, respectively. Durations of the intensive phase were 2.5, 2.7, and 2.5 months while the continuous phase took 4.6, 5.2, and 4.0 months on average in the patients receiving pharmaceutical care, home visit, and modified DOT, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Drug regimen and treatment duration of 1398 included patients categorized by treatment strategy

| Variable | 1398 cases | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical care (n = 315) | Home visit (n = 559) | Modified DOT (n = 524) | ||

| Initial treatment regimen, n (%) | ||||

| 2HRZE/4HR | 309 (98.1) | 546 (97.7) | 517 (98.7) | 0.164a |

| 2HRZES/1HRZE/5HRE | 4 (1.3) | 13 (2.3) | 6 (1.1) | |

| Others | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | |

| Treatment duration, mean (SD) | ||||

| Duration of intensive phase, months | 2.5 (1.4) | 2.7 (1.1) | 2.5 (0.99) | 0.001b |

| Duration of continuation phase, months | 4.6 (2.2) | 5.2 (3.1) | 4.0 (1.4) | <0.001b |

ANOVA analysis of variance, DOT directly observed therapy, E ethambutol, H isoniazid, R rifampicin, S streptomycin, Z pyrazinamide

a Fisher’s Exact test

b One-way ANOVA

Healthcare Resource Uses and Direct Costs Incurred Before and During TB Treatments

In the pre-TB treatment period, the primary healthcare resource use in the patients receiving pharmaceutical care was laboratory investigation $100.55 (95% CI 94.82–106.46); while for those receiving home visit and modified DOT, the main resource use was hospitalization ($137.64, 95% CI 100.92–180.73; and $137.77, 95% CI 111.45–164.91, respectively).

During TB treatment period, the main resource use for the patients receiving pharmaceutical care was medications ($269.33, 95% CI 227.40–324.52). For patients receiving home visit and modified DOT, the main health resource uses included medications, supervision activities, and hospitalization (Table 4).

Table 4.

Mean direct costs per patient by cost category (in 2015 international dollars) incurred to health services and to 1398 patients before and during TB treatment categorized by treatment strategy

| Services | Pharmaceutical care (n = 315) | Home visit (n = 559) | Modified DOT (n = 524) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arithmetic mean (SD) | 95% CI | Arithmetic mean (SD) | 95% CI | Arithmetic mean (SD) | 95% CI | |

| Pre-TB treatment | ||||||

| Medications | 2.51 (8.97) | 1.62–3.61 | 0.16 (1.39) | 0.06–0.28 | 1.96 (9.59) | 1.30–2.75 |

| Laboratory investigation | 100.55 (52.57) | 94.82–106.46 | 27.50 (25.21) | 25.55–29.66 | 21.33 (27.86) | 18.75–23.79 |

| Diagnostic radiology | 28.50 (62.65) | 22.51–35.51 | 18.90 (41.47) | 15.71–22.73 | 14.90 (40.21) | 12.19–18.31 |

| Medical services | 10.47 (26.78) | 7.80–13.19 | 3.32 (2.28) | 3.14–3.52 | 5.26 (4.38) | 4.91–5.66 |

| Miscellaneous costs | 0.46 (3.10) | 0.18–0.83 | 0.55 (1.12) | 0.46–0.65 | 0.04 (0.29) | 0.02–0.06 |

| Hospitalization | 18.02 (218.66) | 2.53–43.98 | 137.64 (502.38) | 100.92–180.73 | 137.77 (348.95) | 111.45–164.91 |

| Total costs | 160.51 (239.07) | 141.26–185.59 | 188.08 (492.02) | 151.99–228.63 | 181.27 (345.40) | 150.99–210.55 |

| Costs to health services | 108.23 (128.51) | 94.11–122.86 | 180.30 (491.39) | 144.04–220.70 | 160.16 (311.25) | 134.71–187.11 |

| Costs to patients | 52.28 (227.35) | 34.73–77.77 | 7.79 (57.64) | 4.01–12.76 | 21.11 (165.22) | 9.53–37.15 |

| TB treatment | ||||||

| Medications | 269.33 (431.09) | 227.40–324.52 | 281.57 (213.33) | 266.33–297.36 | 212.66 (158.38) | 202.55–225.86 |

| Laboratory investigation | 154.53 (133.98) | 140.97–171.08 | 107.58 (70.64) | 102.12–113.33 | 127.81 (104.53) | 119.40–137.27 |

| Diagnostic radiology | 38.47 (43.85) | 34.46–43.28 | 22.46 (15.39) | 21.28–23.80 | 26.66 (30.21) | 24.38–29.30 |

| Medical services | 27.55 (31.48) | 24.45–31.21 | 30.50 (40.51) | 27.72–33.98 | 36.11 (38.74) | 33.23–39.64 |

| Supervision activities | 0 | 218.23 (178.05) | 205.47–232.03 | 217.67 (182.09) | 201.83–233.64 | |

| Miscellaneous costs | 2.60 (16.38) | 1.22–4.57 | 4.08 (8.38) | 3.48–4.70 | 1.93 (4.26) | 1.60–2.29 |

| Hospitalization | 42.42 (624.54) | 0–113.08 | 221.65 (1237.85) | 135.60–326-58 | 133.03 (557.95) | 90.32–181.95 |

| Total costs | 534.91 (879.99) | 451.33–650.14 | 886.07 (1286.99) | 789.66–995.53 | 755.86 (656.35) | 700.76–817.97 |

| Costs to health services | 411.73 (863.56) | 330.99–521.12 | 840.09 (1270.06) | 745.59–948.39 | 727.63 (644.72) | 675.15–789.90 |

| Costs to patients | 123.18 (327.19) | 88.56–165.54 | 45.98 (275.80) | 27.58–70.07 | 28.22 (112.17) | 19.13–38.91 |

| Total | ||||||

| Total costs | 695.41 (904.88) | 609.34–813.10 | 1074.16 (1465.81) | 964.49–1211.83 | 937.12 (768.00) | 872.79–1009.90 |

| Total costs to health services | 519.96 (883.05) | 437.31–625.58 | 1020.39 (1455.52) | 911.13–1154.11 | 887.79 (747.26) | 824.28–955.91 |

| Total costs to patients | 175.45(432.88) | 130.26–230.48 | 53.77 (298.17) | 33.25–79.44 | 49.33 (219.93) | 34.03–69.30 |

Medical services included medical supplies, special diagnostics, medical equipment, operations services, outpatient services, and physical therapy. Miscellaneous costs included food solution, ambulatory care, copayments, other non-medical services, and special physician fees

DOT directly observed therapy, TB tuberculosis

The mean direct costs per patient to the public healthcare payer were $519.96 (95% CI 437.31–625.58), $1020.39 (95% CI 911.13–1154.11), and $887.79 (95% CI 824.28–955.91) for those receiving pharmaceutical care, home visit, and modified DOT, respectively (Table 4). The mean costs to patients were $175.45 (95% CI 130.26–230.48), $53.77 (95% CI 33.25–79.44), and $49.33 (95% CI 34.03–69.30) for those receiving pharmaceutical care, home visit, and modified DOT, respectively (Table 4). The mean total direct costs per patient were $695.41 (95% CI 609.34–813.10), $1074.16 (95% CI 964.49–1211.83), and $937.12 (95% CI 872.79–1009.90) for those receiving pharmaceutical care, home visit, and modified DOT, respectively (Table 4). There was significant difference in mean total costs when comparing pharmaceutical care with either home visit or modified DOT.

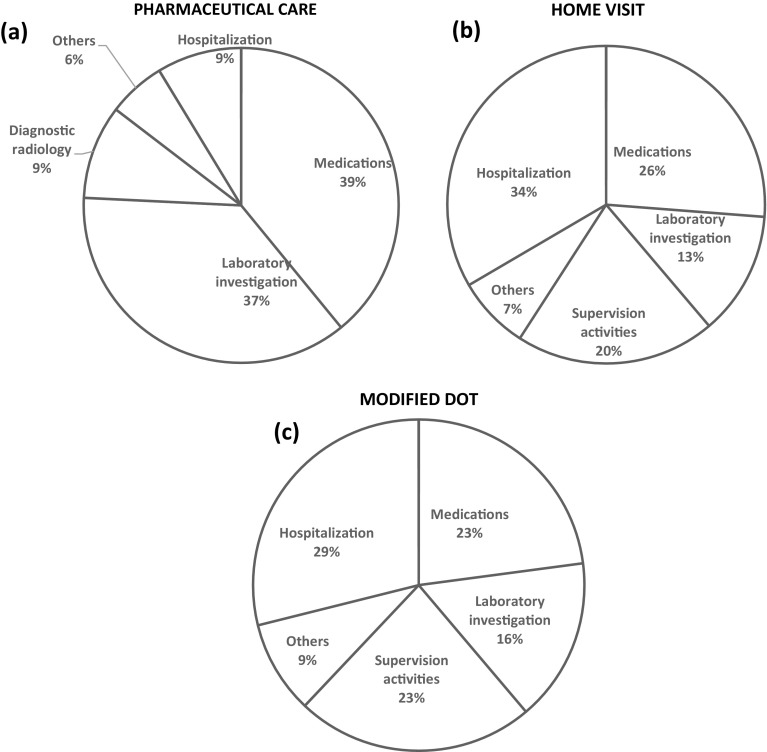

The main expenses for pharmaceutical care were medications and laboratory investigation (39.0 and 36.7% of total costs, respectively). On the other hand, the three largest contributors to total costs in home visit and modified DOT were hospitalizations, medications, and supervision activities (33.4, 26.2, and 20.3% in home visit; 28.9, 22.9, and 23.2% in modified DOT) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Breakdown of total costs incurred for each treatment strategy: a pharmaceutical care, b home visit, and c modified directly observed therapy (DOT). Percentages are proportion of respective sub-component cost out of the total costs

The differences in mean total costs between treatment strategies when adjusted for baseline characteristics were investigated by the GLMs. The P–P and Q–Q plots were similar for models with the same distribution regardless of the link function (Fig. 3). The model performance assessment using the AICs (Table 5) and graphical analyses indicated that the GLMs with the inverse Gaussian distribution and identity link were the best model. After adjustment for baseline characteristics, pharmaceutical care was associated with statistically significant lower direct costs compared with home visit (−$354.95, 95% CI −285.67 to −424.23) and modified DOT (−$264.61, 95% CI −198.76 to −330.46) (Table 6).

Fig. 3.

Normal probability plots (P–P plots) of deviance residuals for the GLMs: a gamma family and identity link; b inverse Gaussian family and identity link. Normal quantile plots (Q–Q plots) of deviance residuals for the GLMs: c gamma family and identity link; d inverse Gaussian family and identity link. Similar plots are obtained with a log link. GLMs generalized linear models

Table 5.

Comparison of GLMs with two different types of distributions and either identity or log link for models including six baseline covariates

| Distributions | Link functions | AIC |

|---|---|---|

| Gamma | Identity | 21,220.19 |

| Log | 21,223.12 | |

| Inverse Gaussian | Identity | 20,720.10 |

| Log | 20,724.58 |

AIC Akaike information criterion, GLMs generalized linear models

Table 6.

Difference in mean total direct costs between the specified group compared with reference group when impact of differences in baseline characteristics was adjusted by GLMs with inverse Gaussian distribution and the identity link

| Variable | Difference in mean costs | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervision strategy | |||

| Home visit | 354.95 | 285.67 to 424.23 | <0.001 |

| Modified DOT | 264.61 | 198.76 to 330.46 | <0.001 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | −5.39 | −54.73 to 43.94 | 0.830 |

| Age group, years | |||

| 25–34 | 123.52 | 44.88 to 202.16 | 0.002 |

| 35–44 | 121.94 | 42.06 to 201.83 | 0.003 |

| 45–54 | 206.00 | 124.45 to 287.56 | <0.001 |

| >55 | 216.28 | 136.55 to 296.02 | <0.001 |

| Local | −148.43 | −232.50 to −64.35 | 0.001 |

| Health insurance | |||

| CSMBS | 18.58 | −55.37 to 92.53 | 0.622 |

| SSS | −98.71 | −168.63 to 28.79 | 0.006 |

| Not covered by public health insurance | 40.14 | −40.19 to 120.46 | 0.327 |

| HIV status | |||

| Yes | 780.04 | 605.67 to 954.41 | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 41.30 | −63.77 to 146.36 | 0.441 |

Statistically significant differences in mean total direct costs are highlighted in bold

References used in each category were supervision strategy (pharmaceutical care), gender (female), age group (18–24 years), habitat (non-local), health insurance (UC), HIV status (no). Significance for all statistical analyses was p < 0.05

CSMBS Civil Servant Medical Benefits Scheme, GLMs generalized linear models, SSS Social Security Scheme, UC Universal Coverage

Discussion

Our previous study has shown that TB treatment success rates for pharmaceutical care are very similar to those for home visit or modified DOT [7]. This cost analysis shows that the pharmaceutical care approach is a relatively simple strategy that requires less healthcare resources and costs compared with the other two approaches. The main health resource uses in the pharmaceutical care group were medications and laboratory investigation. In contrast, the supervision activities were one of the three main resource uses for both home visit and modified DOT groups.

Differences in patient characteristics across treatment strategies may have explained the difference in some healthcare resource uses. The pharmaceutical care group had lower hospitalization costs because almost half (43.5%) of patients traveled from a neighboring province seeking TB care at the study hospital. This implies that their illness might not be severe. If these patients had any severe respiratory condition or required emergency admission, they would have accessed local hospitals. In contrast, the home visit and the modified DOT groups had higher hospitalization costs because these two hospitals are the main provincial referral hospitals under the Ministry of Public Health and generally have higher numbers of TB patients as well as more severe cases. These hospitals are the first choice for local patients who need free and urgent TB care.

The large variation in costs observed in our study is consistent with a systematic review by Laurence et al. [20]. They reported that the costs to healthcare providers varied widely across different and within country income-level groups. Hospitalization accounted for 74% of all provider-incurred costs for treating drug-susceptible TB in all country income groups, but only 12% in upper middle-income countries. They also reported that the mean outpatient costs were 12 times less than hospitalization costs. However, direct costs have reduced over time (between 1990 and 2015) due to the lower admission rates and more ambulatory care in many countries. These trends are supported by previous studies indicating that ambulatory care was clinically effective and cheaper than inpatient hospital care during the first 2 months (intensive phase) [21, 22]. The ambulatory model, therefore, has become the standard of TB care in high-burden countries [23], including Thailand.

Obviously, patients in the pharmaceutical-care group paid 3-fold higher out-of-pocket costs for the TB treatments compared with those receiving home visit and modified DOT. Most of these expenses were direct healthcare costs incurred when patients accessed services outside their district. Apart from the issue of a hospital’s location, the insurance policy is founded on the referral system. Patients in need of specialized treatment would be referred directly to the hospitals under the Ministry of Public Health. Since the study hospital is an academic tertiary hospital, a possible explanation for these patients’ willingness to pay out of pocket may be that they had more confidence in the quality of care provided in this hospital.

In Thailand, the provision for home visit and modified DOT is funded by the Ministry of Public Health, in alignment with the WHO’s recommended strategy and the global fund’s incentives for patient supervision. Advantages of these supervisory activities are to provide close observation in patients’ homes to check if patients have had any difficulty taking TB medications, and to ensure TB screening of the index patients’ family members. In contrast, pharmaceutical care is more recent and differs from the WHO’s recommended strategy, which emphasizes the importance of direct supervision in the initial 2 months of treatment [24]. Our findings shed light on the potential role of the clinical pharmacist in TB outpatient services. Timely pharmacist-led patient education for every outpatient visit and pharmacist-provided telephone consultation required less healthcare resources compared with the other two approaches. A larger scale, prospective study is warranted to generate more robust evidence to support Thai policy making about the most efficient uses of limited resources to fight TB in this developing country.

Our study has limitations. The data used in the analysis came from a retrospective hospital database review. A number of patients had missing information and the approach to handling missing information depended on the type of data. Since this study abstracted costs from hospital databases, only direct healthcare costs were included. In addition, a large proportion of the patients in the pharmaceutical care group came from other regions, the direct non-medical costs and indirect costs (income loss and productivity loss) incurred by them would be expected to be higher than those in the other two hospitals. Further research on the financial burden of TB borne by patients, and health-related quality of life associated with each strategy, was conducted for properly assessing these adherence improvement strategies.

Conclusion

After adjustment for baseline characteristics, pharmaceutical care was associated with lower direct costs compared with home visit and modified DOT.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Eleanor Pullenayegum for her guidance with the statistics used in this study.

Author contributions

All authors developed the conception and design of the study; PT performed the data collection, analyzed the data, and prepared the manuscript; FX, ML, and JD performed critical revision of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

All authors (PT, FX, ML, and JD) have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to protecting participant confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Transparency declaration

This research was a part of a retrospective cohort study in which the result on the comparative effectiveness of pharmaceutical care versus to home visit and modified DOT was previously publish in the Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics [7], whereas this study focused on health care resource uses and costs associated to those three different strategies. The material regarding study participants was reproduced from the published article [7] with permission from the copyright owner (John Wiley and Sons).

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). Global tuberculosis report 2015. 2015. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/gtbr15_main_text.pdf. Accessed 20 Dec 2015.

- 2.Cambanis A, Ramsay A, Yassin MA, Cuevas LE. Duration and associated factors of patient delay during tuberculosis screening in rural Cameroon. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12(11):1309–1314. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramsay A, Al-Agbhari N, Scherchand J, Al-Sonboli N, Almotawa A, Gammo M, et al. Direct patient costs associated with tuberculosis diagnosis in Yemen and Nepal. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14(2):165–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cambanis A, Yassin MA, Ramsay A, Squire SB, Arbide I, Cuevas LE. A one-day method for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in rural Ethiopia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10(2):230–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirao S, Yassin MA, Khamofu HG, Lawson L, Cambanis A, Ramsay A, et al. Same-day smears in the diagnosis of tuberculosis. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12(12):1459–1463. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization (WHO). Treatment of Tuberculosis: guidelines, 4th ed. 2010. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241547833_eng.pdf. Accessed 10 Sept 2013.

- 7.Tanvejsilp P, Pullenayegum E, Loeb M, Dushoff J, Xie F. Role of pharmaceutical care for self-administered pulmonary tuberculosis treatment in Thailand. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2017;42(3):337–344. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tangcharoensathien V, Patcharanarumol W, Chitpranee, Prakongsai P, Jongudomsuk P, Srithamrongsawat S, et al. Thailand health financing review 2010. 2010. http://ssrn.com/abstract=1623260. Accessed 10 June 2016.

- 9.World Health Organization (WHO). Global tuberculosis report 2016. 2016. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/250441/1/9789241565394-eng.pdf. Accessed 20 March 2017.

- 10.World Bank. Inflation, consumer prices (annual %) in the World Bank Database. 2015. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FP.CPI.TOTL.ZG?end=2014&locations=TH&start=2011. Accessed 11 June 2016.

- 11.World Bank. PPP conversion factor, private consumption (LCU per international $) in the World Bank Database. 2015. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/PA.NUS.PRVT.PP?end=2015&locations=TH&start=2011. Accessed 11 June 2016.

- 12.Thompson SG, Barber JA. How should cost data in pragmatic randomised trials be analysed? BMJ. 2000;320(7243):1197–1200. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7243.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barber JA, Thompson SG. Analysis of cost data in randomized trials: an application of the non-parametric bootstrap. Stat Med. 2000;19(23):3219–3236. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20001215)19:23<3219::AID-SIM623>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barber J, Thompson S. Multiple regression of cost data: use of generalised linear models. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2004;9(4):197–204. doi: 10.1258/1355819042250249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dodd S, Bassi A, Bodger K, Williamson P. A comparison of multivariable regression models to analyse cost data. J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12(1):76–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moran JL, Solomon PJ, Peisach AR, Martin J. New models for old questions: generalized linear models for cost prediction. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13(3):381–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindsey JK, Jones B. Choosing among generalized linear models applied to medical data. Stat Med. 1998;17(1):59–68. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19980115)17:1<59::AID-SIM733>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gan FF, Koehler KJ, Thompson JC. Probability plots and distribution curves for assessing the fit of probability models. Am Stat. 1991;45:14–21. [Google Scholar]

- 19.IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0. 2015.

- 20.Laurence YV, Griffiths UK, Vassall A. Costs to health services and the patient of treating tuberculosis: a systematic literature review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(9):939–955. doi: 10.1007/s40273-015-0279-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Jonghe E, Murray CJ, Chum HJ, Nyangulu DS, Salomao A, Styblo K. Cost-effectiveness of chemotherapy for sputum smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis in Malawi, Mozambique and Tanzania. Int J Health Plann Manag. 1994;9(2):151–181. doi: 10.1002/hpm.4740090204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray CJ, DeJonghe E, Chum HJ, Nyangulu DS, Salomao A, Styblo K. Cost effectiveness of chemotherapy for pulmonary tuberculosis in three sub-Saharan African countries. Lancet. 1991;338(8778):1305–1308. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92600-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dye C, Floyd K, et al. Tuberculosis. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, et al., editors. Disease control priorities in developing Countries. 2. Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank Group; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization (WHO). What is DOTS?: A guide to understanding the WHO-recommended TB control strategy known as DOTS. 1999. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/65979/1/WHO_CDS_CPC_TB_99.270.pdf. Accessed 5 Aug 2016.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.