Abstract

Stevia rebaudiana is an important source of natural steviol glycosides and is of increasing interest in various fields of study. Therefore, understanding the molecular processes regulating its metabolism is of great importance. In this study, the stability of seven reference genes (18S ribosomal RNA, Actin, Aquaporin, Calmodulin, Eukaryote elongation factor 1-α, Malate dehydrogenase, and Ubiquitin) under the effect of three stress-related elicitors (methyl jasmonate, salicylic acid, and spermidine) was evaluated in stevia plants. We used RefFinder software, which makes use of the four main currently available algorithms for reference gene selection: geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, and the Comparative ∆Ct method. The results indicated that Ubiquitin and Actin can be used as reference genes under all tested experimental conditions. The genes, 18S ribosomal RNA, traditionally used as a reference gene, along with Calmodulin, showed the lowest stability. The expression of Deoxyxylulose-5-phosphate synthase and Kaurenoic acid hydroxylase genes was used to confirm the validated reference genes, showing that inadequacy of the reference gene may lead to erroneous results. This is the first study on the stability of reference genes in Stevia rebaudiana plants, and is of great relevance for further analysis of the gene expression of the steviol glycoside biosynthetic pathway.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12298-018-0583-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Gene expression, Methyl jasmonate, Salicylic acid, Spermidine, Stevia, Transcript normalization

Introduction

Stevia rebaudiana (Bert.), known as stevia, is a perennial herb of the family Asteraceae, and the extracts from its leaves have been used for decades to sweeten foods and beverages in North Korea, Japan, and China (Madan et al. 2010). The primary components responsible for the sweetness of this plant are steviol glycosides (SGs), which according to Ceunen and Geuns (2013), are a mixture of at least 34 different compounds including stevioside and rebaudioside A, the major components found in stevia leaves.

Stevia plants have received increasing attention in different fields of research, mainly due to a number of medicinal properties, e.g. antihyperglycemic (Jeppesen et al. 2002), antihypertensive (Melis and Sainati 1991; Melis 1995), antioxidant, and anticancer effects (Tadhani et al. 2007; Jayaraman et al. 2008; Kumar et al. 2012). Parallel to this, stevia shows great potential as an agricultural crop for the production of a high-potency natural sweetener (Lemus-Mondaca et al. 2012). In short, stevia-based sweeteners are being intensively investigated and the search for new compounds is ongoing (Wölwer-Rieck et al. 2012).

SG biosynthesis occurs mainly in the leaves (Brandle and Telmer 2007) and partially shares some pathway steps with gibberellic acid (GA) biosynthesis. Two enzymes seem to play a central role in this process. These include deoxyxylulose-5-phosphate synthase (DXS), the first enzyme of 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate (MEP) pathway, and kaurenoic acid hydroxylase (KAH), an important branch point of divergence of steviol biosynthesis from gibberellin biosynthesis, since KAH catalyses the hydroxylation of kaurenoic acid into steviol, which is a common precursor for SG biosynthesis (Brandle and Telmer 2007; Cordoba et al. 2009).

Chen et al. (2014) identified over 100 genes involved in the biosynthetic pathway of SGs. In another approach, Singh et al. (2017), through sequencing analysis, revealed potential targets for manipulating these paths.

Although the biosynthesis of SGs is well-elucidated, the expression of the genes involved in this pathway, as well as the physiological processes that define expression levels in stevia plants are little understood. Overall, there is scarce information regarding the regulation of the SG biosynthesis pathway as well as the transcription factors and master switches involved in this regulation (Lucho et al. 2018). To assess changes in gene expression, reverse transcription followed by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) is one of the most widely used techniques due to its high sensitivity, reproducibility, and specificity (Bustin et al. 2010; Derveaux et al. 2010; Yi et al. 2012). The most commonly used approach to normalize data of gene expression by RT-qPCR is the use of one or more reference genes (Radoni et al. 2004; Hugget et al. 2005).

Genes involved in basic cellular processes, primary metabolism, and cellular maintenance are commonly used as reference genes. Actin (ACT), Ubiquitin (UBQ), Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), ribosomal genes (18S and 28SrRNA), Cyclophilin (CYP), Eukaryotic elongation factor 1-α (eEF-1α), and Malate dehydrogenase (MAL) are a few of the most traditional reference genes used in gene expression studies (Kim et al. 2003; Reid et al. 2006; Lee et al. 2010; Mallona et al. 2010; Moraes et al. 2015; Rickes et al. 2016). However, recent studies have indicated that the expression of these traditional reference genes is not stable, especially when tested in other species or under a wide range of experimental conditions (Radoni et al. 2004; Czechowski et al. 2005). Seven candidate reference genes were selected and tested in this study: ACT, UBQ, and 18S have already been used in gene expression analysis with stevia plants (Hajihashemi et al. 2013; Modi et al. 2014; Hajihashemi and Geuns 2016), MAL and eEF-1 (Reid et al. 2006; Moraes et al. 2015) are traditionally used in other species, while CALM and AQP are new reference genes.

In view of the wide range of possibilities regarding the use of stevia plants, in-depth studies at the molecular level are necessary, because there are no data in the literature regarding the transcriptional profile under the effect of elicitor agents. Elicitors may be chemical or biological agents, able to induce morphological or physiological alterations in the organism under study (Zhao et al. 2005).

Elicitor-containing media have been indicated as stimulators of biosynthesis of secondary metabolites in plant tissue culture, by altering metabolic pathways and qualitatively and quantitatively affecting the resulting bioactive molecules (Djilianov et al. 2005). Among the plant elicitors, methyl jasmonate (MeJa) (Wang et al. 2013), salicylic acid (SA) (Rodrigues-Brandão et al. 2014; Loc et al. 2016), and polyamines, particularly spermidine (SPD) (Liu et al. 2007; Khalil et al. 2016), are the most studied, due to their involvement in the cascade of events that cause an increase in the accumulation of secondary metabolites.

The objective of this work was to evaluate the expression stability of reference genes to be used in RT-qPCR studies in the leaves of stevia plants in response to the stress-related elicitor agents methyl jasmonate, salicylic acid, and spermidine. To demonstrate the effectiveness of the selected references genes, we analysed the expression of two target genes, Deoxyxylulose-5-phosphate synthase (DXS) and Kaurenoic acid hydroxylase (KAH), both involved in the SG biosynthesis pathway.

Materials and methods

Plant material and experimental conditions

In our laboratory, stevia plants were established in vitro from nodal explants and micropropagated on MS basal medium (Murashige and Skoog 1962), supplemented with 30 g L−1 sucrose, 100 mg L−1 myo-inositol, 7 g L−1 agar, and 1 mI L−1 of Plant Preservative Mixture™ (Apollo Scientific Ltd., UK). All cultures were maintained at 25 ± 2 °C in a growth chamber with a 16 h photoperiod (22 µmol m−2 s−1 PAR).

After 30 days of in vitro culture, stevia plants were removed from the culture medium and the roots washed in water to remove residues of the culture medium, and transferred to plastic trays (20 × 7 × 3 cm), containing the substrates Plantmax® and vermiculite (1:1). The plants were watered every two days, and treated every three days with half strength Hoagland nutrient solution (Hoagland and Arnon 1950), for 30 days in a growth room under a 16 h photoperiod, at 25 °C ± 1.

Thereafter, plants were transferred to a continuous-flow hydroponic system with floating roots and half-strength Hoagland solution for 2 days, to acclimate the roots to the system. The control treatment was half-strength Hoagland solution (T1), and the other treatments consisted of the same solution with 100 μM methyl jasmonate (T2), 100 μM spermidine (T3), and 100 μM salicylic acid (T4). The leaves of these plants were collected over a period of 4 days at intervals of 24 h and named according to the period of elicitation (C1, C2, C3, and C4, i.e. C1 = 24 h, C2 = 48 h, C3 = 72 h, and C4 = 96 h).

The experiment was arranged in a completely randomized 4x4 factorial design, with three elicitor agents plus a control (without elicitors) and four periods of exposure to the elicitor agents. For each combination, three biological repetitions were performed, each of which consisted of one pot with five plants.

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from 100 mg of leaves using Plant RNA Reagent Purilink® (USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA concentration and purity were determined with a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies, USA), and the RNA quality and integrity were assessed by 1.0% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Two micrograms of total RNA were reverse transcribed into cDNA with a final volume of 20 µL, using the kit oligo (dT) primer and Super Script First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen®-18080093, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Selection of reference genes and primer design

Seven candidate reference genes were selected for qPCR analysis in this study (ACT, UBQ, 18S, MAL, eEF-1α, CALM, and AQP). Primers were designed based on S. rebaudiana oligonucleotide sequences from the GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/), using the software PerlPrimer, and set as follows: a melting temperature (Tm) of 58–62 °C and a guanine-cytosine (GC) content between 45 and 55%. All primer sequences and relevant gene information are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Candidate reference gene description and parameters derived from RT-qPCR analysis

| Gene symbol | Primer sequence (5′–3′) (forward/reverse) | Gene Bank accession | Amplicon lenght | Efficiency | Product Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18S b | CCGGCGACGCATCATT/AGGCCACTATCCTACCATCGAA | AB457558 | 59 | 1.86 | 73.5 |

| ACT a | CGCCATCCTCCGTCTTGATCTTGC/CCGTTCGGCGGTGGTGGTAA | ` | 100 | 1.98 | 75.5 |

| AQP | AATCTGTGGTGTGGGTTTGG/TTCTCTTAGGATCAGTAGCCGA | DQ269455 | 97 | 2.19 | 79.0 |

| CALM | TGATGCTGATGGAAATGGGA/CAACTTCTCACCAAGATTTGTC | AF468661 | 183 | 2.13 | 74.5 |

| eEF-1a | ATGCTCTTCTTGCTTTCACTC/GATTTCTTCATACCTCGCCT | AY157315 | 103 | 1.99 | 74.5 |

| MAL | TCATCTCCATCCTTCAAATGTCC/TTGACCAATTCCTCCAGCAG | DQ269456 | 126 | 2.17 | 77.0 |

| UBQ a | TCACTCTTGAAGTGGAGAGTTCCGA/GCCTCTGTTGGTCCGGTGGG | AF548026 | 90 | 2.10 | 76.5 |

| DXS a | AAGGTCGAATTCGCTGGGG/TCCTGAGTGGTGAGGTTTTTCA | AF548026 | 89 | 2.05 | 78.5 |

| KAH a | AACTCTGGCACTCCTACGTG/CAAAACGGTCGCCAAACAAC | AF548026 | 119 | 1.89 | 81.0 |

RT-qPCR reactions

RT-qPCR reactions were performed in a Bio-Rad CFX Real Time Thermal Cycler, USA, using the Universal FastStart SYBR Green Master (Rox) kit (Hoffmann-la Roche®) under the following amplification conditions: 95 °C for 10 min; 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s; 60 °C for 1 min, and a melting curve analysis at 65–95 °C, with temperature increments of 5 °C for each fluorescence measurement. Each assay included three technical and biological replicates.

PCR efficiency (E) was determined at four serial cDNA dilutions (1:1, 1:5, 1:25, and 1:125). The E value was estimated by the equation E = 10(−1/slope) (Rasmussen 2001), where the slope corresponds to the inclination of the line obtained from the regression between the cycle quantification (Cq) values of the transcripts and the logarithm values of the different cDNA dilutions (standard efficiency curve). Efficiency values between 1.8 and 2.2 were considered as acceptable, i.e. a reaction efficiency between 90 and 110%. Three technical replicates were performed for each reaction.

Data analyses and statistical tools for normalization

The expression of the seven reference genes was indicated by the cycle quantification (Cq) value, the number of cycles required until fluorescence reached a certain detection threshold. To estimate the stability of the reference genes, we used four tools: Comparative ∆Ct method, BestKeeper, NormFinder, and geNorm (Vandesompele et al. 2002; Andersen et al. 2004; Pfaffl et al. 2004; Silver et al. 2006). The final rank of the reference genes was determined with the RefFinder program (Xie et al. 2012), a tool developed for the assessment and screening of reference genes, which integrates the Comparative ΔCt method, BestKeeper, NormFinder, and geNorm approaches (Xie et al. 2012).

The Comparative ∆Ct method determines the most stable reference genes by comparing the relative expression levels of “pairs of genes” in each sample or treatment considering the means of the SD values (Andersen et al. 2004), while the BestKeeper algorithm evaluates the stabilities of candidate reference genes based on CV ± SD values and its relationship to the BestKeeper index (Pearson correlation coefficient r and p values) (Pfaffl et al. 2004). The NormFinder algorithm uses ANOVA for the analyses of inter and intra-group variations among samples to determine the stability value (Andersen et al. 2004). geNorm classifies the stability of gene expression by calculating the average expression stability (M). Stably expressed genes have values below 1.5, while an M-value of more than 1.5 indicates a lower expression stability (Vandesompele et al. 2002).

The optimal number of reference genes for normalization

The optimal number of reference genes to be used for data normalization was calculated using the geometric mean of the most stable genes. The variation of consecutive pairs was then calculated as suggested by the geNorm algorithm (Vandesompele et al. 2002).

Validation of the reference genes

To confirm the reliability of potential reference genes, the expression profile of DXS (Deoxyxylulose-5-phosphate synthase) and KAH (Kaurenoic acid hydroxylase), two enzymes involved in steviol glycoside biosynthesis were quantified and normalized with the two most stable (UBQ and ACT) and least stable genes (18S and CALM), as determined by RefFinder, when all treatments were analysed together. The RT-qPCR amplification conditions were as described above. The data of relative expression were calculated according to the method 2−ΔΔCq (Livak and Schmittgen 2001). For statistical analyses, one-way ANOVA and the post hoc Tukey test (5%) were performed using the R software.

Results and discussion

Amplification specificity and efficiency of candidate reference genes

In this study, specific amplification of reference genes was confirmed by the existence of a single peak in the melting curve (see Supplementary Figure 1). In addition, no amplification signals were detected in the control samples (no template), or in the reactions of the negative control for reverse transcriptase. The efficiency of amplification (E) of the candidate reference genes ranged from 1.86 (18S) to 2.19 (AQP), indicating high efficiency. The Tm for all PCR products ranged from 73.5 °C (18S) to 79 °C (AQP), i.e. the expected range for amplicons based on the GC composition (in %) and length, used as criterion for the primer design (Table 1).

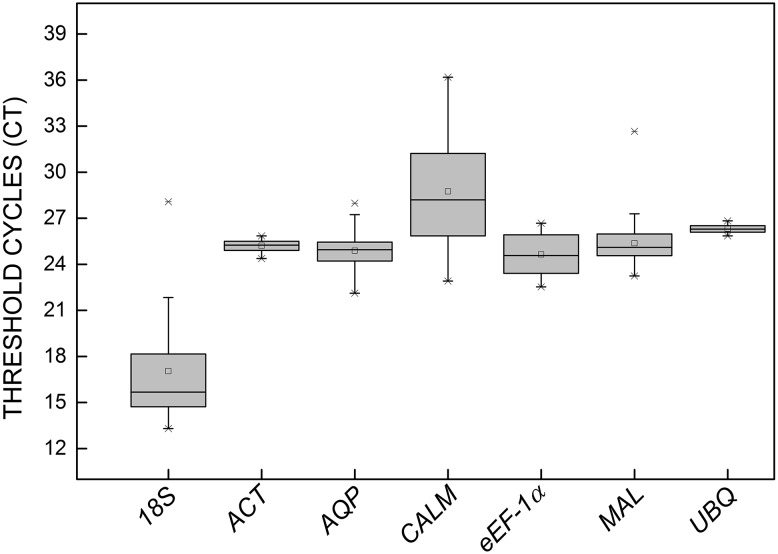

To be considered as a reference gene, the expression levels should remain constant in the evaluated samples. Therefore, to determine transcript levels for each reference gene we used the quantification cycle (Cq) values. The results show that CALM was the least expressed gene, with the highest mean Cq in the samples (28.74), whereas 18S was the most expressed gene, with the lowest mean Cq (17.04). In addition, the variation in expression levels of CALM and 18S was greater than of the other genes, which can be seen by the larger whisker caps and boxes (Fig. 1), while UBQ and ACT had the lowest variation in expression.

Fig. 1.

Expression levels of different reference genes. Expression data displayed as RT-qPCR quantification cycle (Cq) values for each reference gene of Stevia rebaudiana. The line across the box represents the median. The box indicates the 25th and 75th percentiles and whisker caps represent the maximum and minimum values. The higher the boxes and whiskers, the greater is the variation

Galli et al. (2015) evaluated the expression levels of reference genes in two subsets samples composed of a combination of strawberry cultivars, and subjected to two osmotic stress conditions (salinity and drought). In both subsets, the expression level of the 18S gene was the highest of the reference genes. Similar results were reported by Wei et al. (2013) in an evaluation of 10 reference genes in sesame samples subjected to different stresses and hormone treatments; the 18S gene also showed the highest expression.

Expression stability of candidate reference genes under the effect of elicitors

The ideal reference gene should have comparable expression regardless of experimental conditions, including different developmental stages, tissues, and sample treatments. Therefore, to allow the evaluation of target gene expression in stevia plants in response to stress-related elicitors (MeJa, SA, and SPD), it is extremely important to identify reference genes with a stable expression to normalize expression data. The stability of the candidate reference genes was evaluated through the Comparative ∆Ct method, BestKeeper, geNorm, NormFinder, and RefFinder.

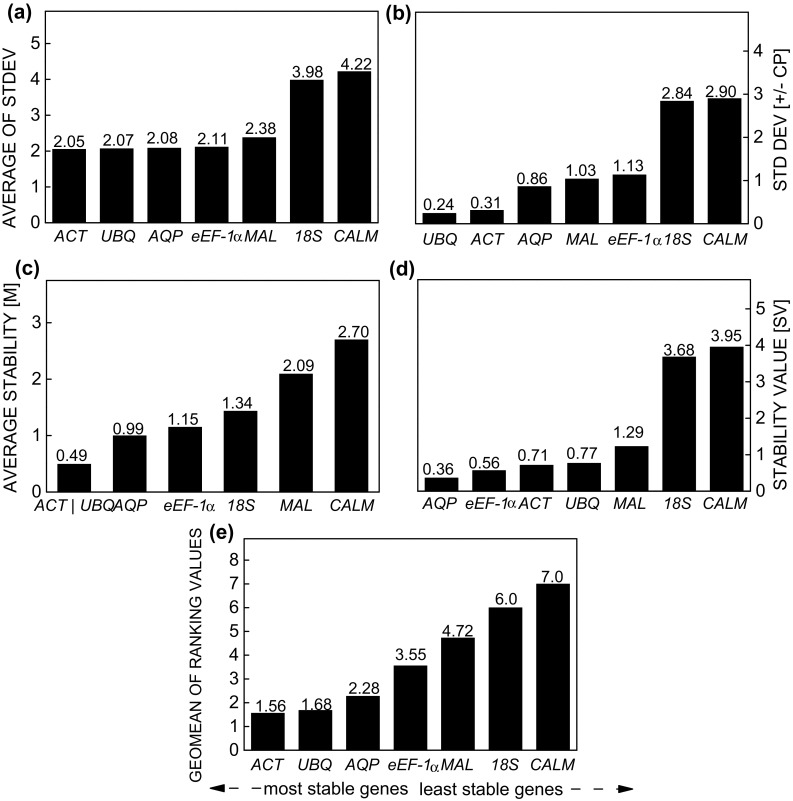

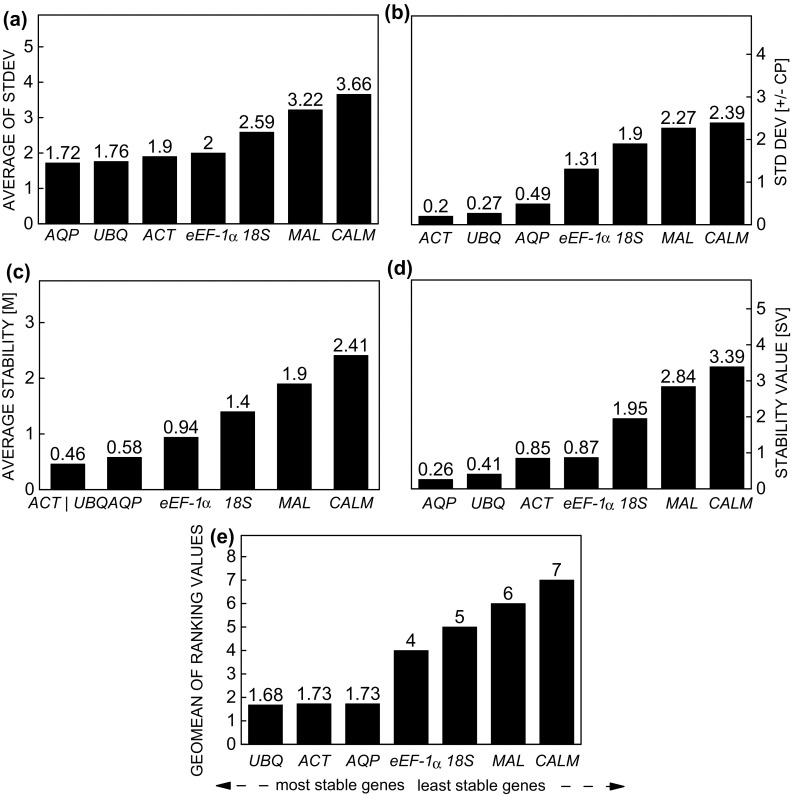

In general, the results of each of the methods were similar, when all treatments were analysed together (Fig. 2). The most unstable gene was CALM, followed by 18S, except for when analysed with geNorm, in which instability was highest for MAL, suggesting that these genes are inadequate for the normalization of RT-qPCR data under the experimental conditions evaluated. Among the candidate reference genes assessed by the Comparative ∆Ct method, the most stable gene was ACT, followed by UBQ and AQP (Fig. 2a). This stability of expression was also observed for BestKeeper, where UBQ, ACT, and AQP were the only genes with a standard deviation (SD) below 1.0 (Fig. 2b). However, by geNorm, only MAL and CALM had values above the mean expression stability (M) > 1.5 (the cut-off), and thus were considered the most unstable, while by this same method, ACT, UBQ, and AQP were the most stable (Fig. 2c). In addition to these genes, NormFinder also identified eEF-1α as stable (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2.

Expression stability of reference genes in Stevia rebaudiana under the separate effects of three elicitors (methyl jasmonate, salicylic acid, and spermidine), calculated by the comparative ∆Ct method (a), BestKeeper (b), geNorm (c), NormFinder (d), and RefFinder (e)

Although the algorithms of each method are based on different approaches (Andersen et al. 2004), the order of stability of the reference genes remained similar in the samples evaluated. To obtain clearer results for the most stable reference genes, as recommended by the others methods, we calculated the geometric mean of corresponding rankings for each reference gene when all treatments were analysed together, according to the RefFinder approach (Stajner et al. 2013). According to these results, the ranking of stability was ACT > UBQ > AQP > eEF-1α > MAL > 18S > CALM (Fig. 2e).

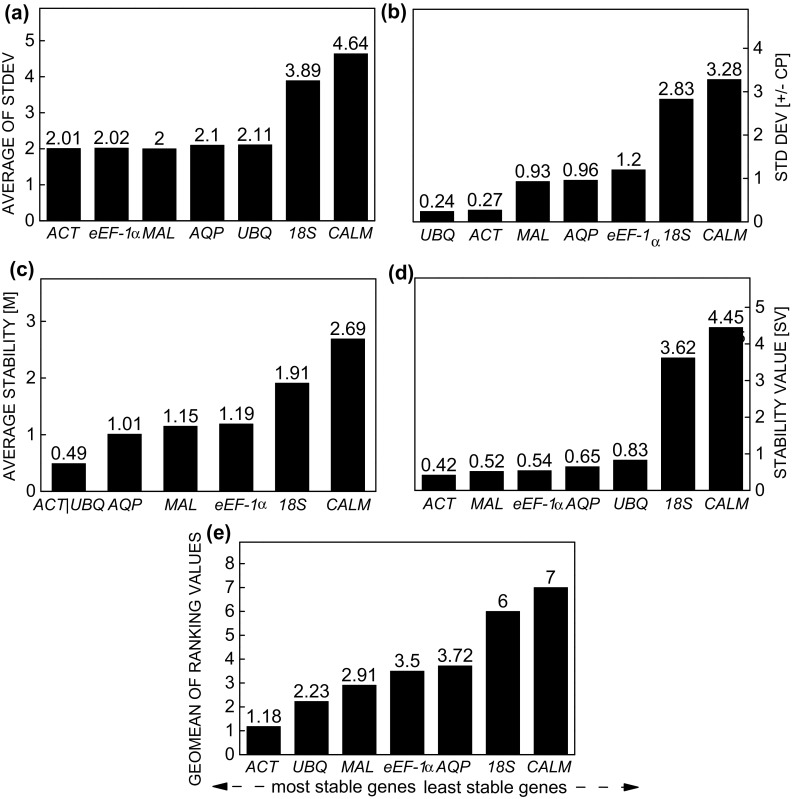

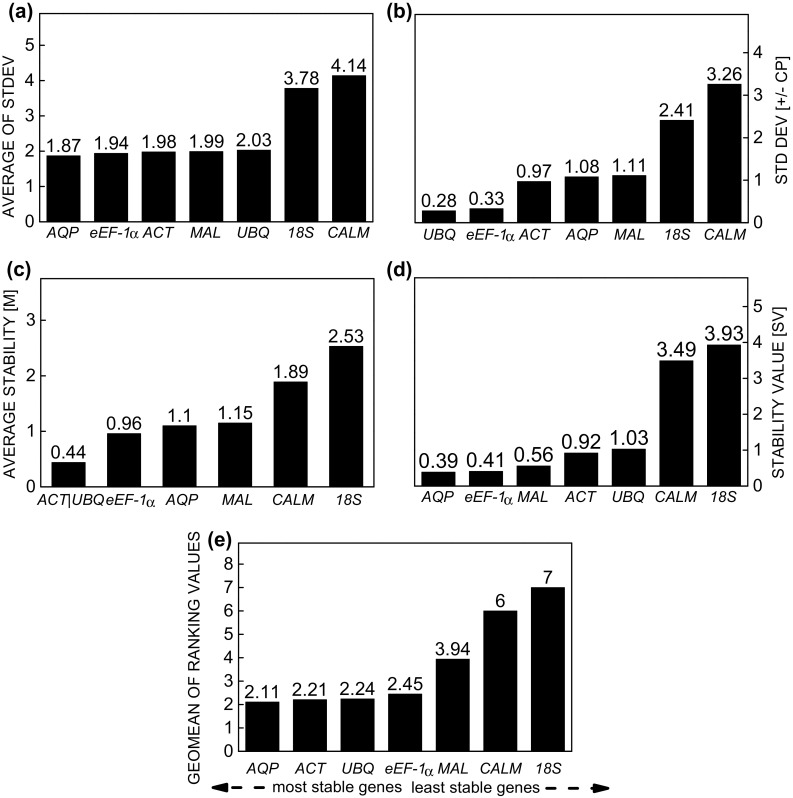

When using the elicitor agent MeJa, the stability level of reference genes ACT, eEF-1α, MAL, AQP, and UBQ was highest by the Comparative ∆Ct method (Fig. 3a). By the BestKeeper method, UBQ was the most stable gene, followed by ACT, since these two genes showed the lowest standard deviation (0.24 and 0.27, respectively), while MAL and AQP were also below the cut-off point (Fig. 3b). As in the previous method, geNorm identified ACT and UBQ as the most stable reference genes; however, only 18S and CALM had an M value below the cut-off point (Fig. 3c). According to NormFinder, the candidate reference genes ACT, MAL, eEF-1α, AQP, and UBQ were the most stable (Fig. 3d). Based on these results, the ranking of gene stability recommended for the elicitor MeJa, indicated by the integrated analysis of RefFinder, was: ACT > UBQ > MAL > eEF-1α > AQP > 18S > CALM (Fig. 3e).

Fig. 3.

Expression stability of reference genes in Stevia rebaudiana under effect of the elicitor methyl jasmonate calculated by the comparative ∆Ct method (a), BestKeeper (b), geNorm (c), NormFinder (d), and RefFinder (e)

For the elicitor SA, the Comparative ∆Ct method and NormFinder indicated that AQP and UBQ were the most stable genes (Fig. 4a, d). When geNorm and BestKeeper were used, the most stable genes were ACT/UBQ and ACT and UBQ, respectively (Fig. 4b, c). However, instability increased in all methods when CALM was used as a reference gene. The ranking of stability by RefFinder was: UBQ > ACT > AQP > eEF-1α > 18S > MAL > CALM (Fig. 4e).

Fig. 4.

Expression stability of the reference genes in Stevia rebaudiana under effect of the elicitor salicylic acid, calculated by the comparative ∆Ct method (a), BestKeeper (b), geNorm (c), NormFinder (d), and RefFinder (e)

According to NormFinder and the Comparative ∆Ct method, the stability of AQP and eEF-1α was greatest when using SPD (Fig. 5a, d). For BestKeeper, the genes UBQ, eEF-1α, and ACT were the most stable and the only genes with values below the cut-off point (Fig. 5b), while ACT/UBQ and eEF-1α were the least stable for geNorm; only CALM and 18S exceeded the cut-off point (Fig. 5c). According to RefFinder, stability was ranked: AQP > ACT > UBQ > eEF-1α > MAL > CALM > 18S (Fig. 5e). Although the most unstable genes remained the same, the reference genes with the highest stability varied between treatments, confirming that different experimental conditions induced different responses at the cellular level.

Fig. 5.

Expression stability of the reference genes in Stevia rebaudiana under effect of the elicitor spermidine, calculated by the comparative ∆Ct method (a), BestKeeper (b), geNorm (c), NormFinder (d), and RefFinder (e)

Overall, in our study, one of the most unstable genes in all samples was 18S, indicating its inadequacy for the normalization of expression of RT-qPCR data, corroborating other studies, where this gene has been suggested to be inappropriate for use as a reference gene in maize grain (Galli et al. 2013), strawberry (Giri and Zaheer 2016), rice (Li et al. 2009), and radish samples (Xu et al. 2012). Furthermore, the stability of gene CALM was also low, which can be explained by its involvement in many cellular processes, responding to a series of environmental stimuli (Knight and Knight 2001; Reddy et al. 2016; Yang et al. 2013). The eEF-1α gene, another traditional reference gene, presented substantial variation in our study, as well as in studies on rice (Moraes et al. 2015) and sugar cane (Guo et al. 2014; Ling et al. 2014).

The genes ACT and UBQ are traditionally used as reference genes, and our results shows that their stability was high in all treatments, confirming the findings of several other studies (Jian et al. 2008; Chang et al. 2012; Duhoux and Dlye 2013; Fan et al. 2013; Chen et al. 2015). Additionally, the AQP gene was stable in plants treated with SA and SPD, and can be used as a new reference gene when stevia plants are subjected to these treatments. Our results confirm that, generally speaking, no reference gene is universally applicable for all experimental conditions and that the traditional reference transcripts do not always represent the constitutive expression, as is often assumed.

The optimal number of reference genes for normalization

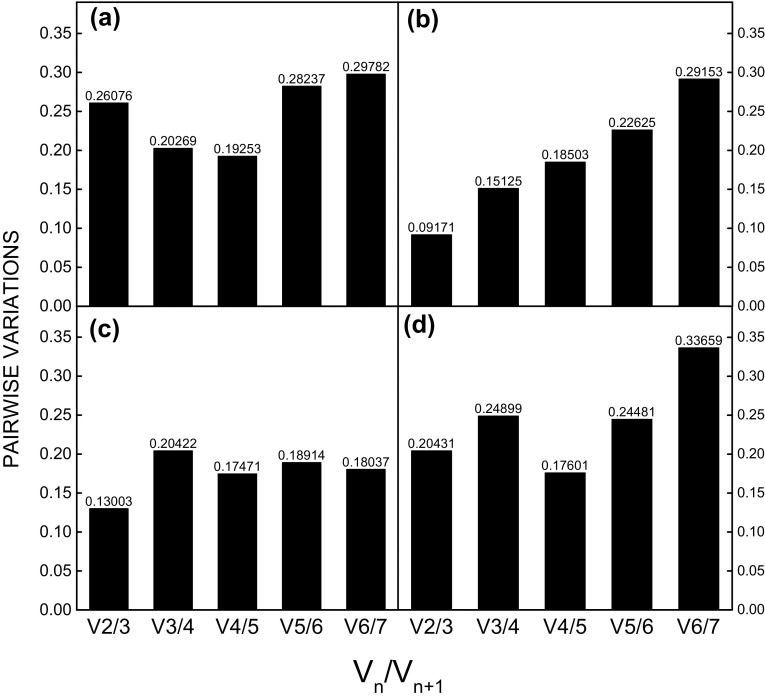

The optimal number of reference genes required for gene expression normalization for the various sample groups was determined using geNorm. Variation greater than 0.15 was assumed to be significant (Vandesompele et al. 2002), and according to this criterion, V2/3 values below the cut-off (0.15) were registered when using the elicitors MeJa and SA (0.130 and 0.091, respectively) (Fig. 6b, c), suggesting that two reference genes are sufficient to normalize expression data in these samples.

Fig. 6.

Pairwise variation (V) calculated by geNorm to determine the minimum number of reference genes for accurate normalization in. Stevia rebaudiana samples. a Elicitors agents (methyl jasmonate, salicylic acid, and spermidine) analyzed together, b methyl jasmonate, c salicylic acid and d spermidine

When the elicitor agent SPD and all treatments were analysed together the values exceeded the cut-off point (Fig. 6a, d), although it has been suggested that this cut-off value is too strict (Vandesompele et al. 2002). Therefore, for these two conditions, we recommend the use of at least four reference genes, with values within an acceptable range for certain groups of samples (Hellemans et al. 2007; Chen et al. 2015).

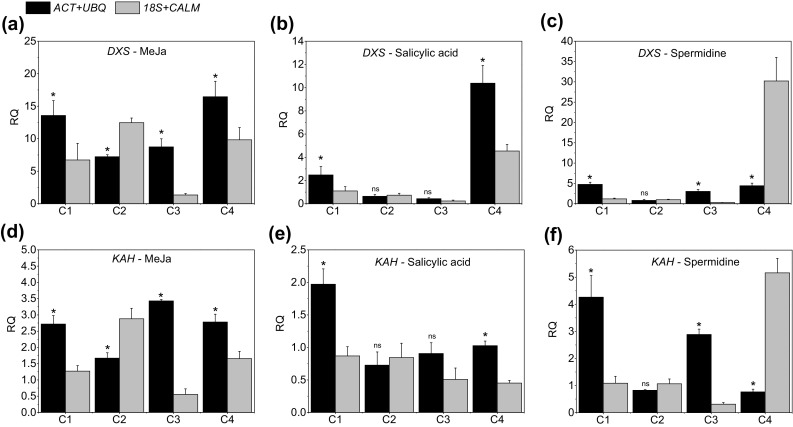

Validation of the reference genes

The DXS and KAH genes encode enzymes involved in steviol glycoside biosynthesis, and their expression is altered by a series of factors, such as growth regulators and chemical compounds (Kumar et al. 2012; Hajihashemi et al. 2013; Modi et al. 2014). Therefore, to detect the influence of different genes on data normalization, we assessed the relative expression of DXS and KAH by using the best (ACT and UBQ) and the least stable (18S and CALM) reference genes.

In the assessment of the gene expression of DXS in MeJa-treated plants, a significant difference (P < 0.05) was observed at all sampling times, especially for C3, which showed up to 6.5-fold difference, depending on the combination of normalization used (Fig. 7a). This significant difference was also observed for the elicitor SA in C1 and especially in C4 (Fig. 7b). For SPD, there was a significant difference only in C2 (Fig. 7c). The result for the KAH gene was statistically equal to that found for DXS. Expression stimulated by the elicitor MeJA showed the largest difference at C3 (Fig. 7d). However, for the elicitors SA and SPD the expression difference was mainly evident in C1 and C4 (Fig. 7e, f).

Fig. 7.

Expression profile of DXS (a–c) and KAH (d–f) in Stevia rebaudiana plants under effect of the elicitors methyl jasmonate, salicylic acid, and spermidine, respectively, at four sampling times. The most stable combination of reference genes (ACT and UBQ) and the two least stable reference genes (18S and CALM) were used to normalize expression data. Samples from the control treatment were used as reference samples. The data show the mean expression ± standard deviation, calculated from three biological replicates

Conclusions

The evaluation of the expression of seven reference genes in Stevia rebaudiana leaves under the effect of the three stress-related elicitors (MeJa, SA, and SPD) showed that ACT and UBQ can be used as reference genes in all treatments. On the other hand, the stability of the gene expression of 18S, traditionally used as a reference gene, and of CALM, was insufficient and therefore not indicated in this study. The analysis of the expression of DXS and KAH confirms the importance of validating genes of reference to achieve accurate results in RT-qPCR. This study is highly relevant for further analysis of the gene expression of the SG biosynthetic pathway.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 1 Specificity of reference genes for Stevia rebaudiana under the effect of elicitors agents (methyl jasmonate, salicylic acid, and spermidine) (TIFF 1526 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico) for their financial support and research fellowship EJBB, the CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior) and the FAPERGS (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Rio Grande do Sul) for supporting the research.

Abbreviations

- ACT

Actin

- AQP

Aquaporin

- CALM

Calmodulin

- CYP

Cyclophilin

- DXS

Deoxyxylulose-5-phosphate synthase

- eEF-1α

Eukaryotic elongation factor 1-α

- GA

Gibberellic acid

- GAPDH

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase

- KAH

Kaurenoic acid hydroxylase

- MAL

Malate dehydrogenase

- MeJa

Methyl jasmonate

- MEP

2-c-methyl-D-erythritol-4 phosphate

- SA

Salicylic acid

- SGs

Steviol glycosides

- SPD

Spermidine

- UBQ

Ubiquitin

- 18S

18S ribosomal RNA

Authors’ contribution

Conceived and designed the experiments: SRL, LCB, AMK, and EJBB. Performed the experiments: SRL, CM and AMK. Analysed the data: SRL, MNA, VJB and EJBB. Wrote the paper: SRL and MNA. Corrected the manuscript: LCB, VJB and EJBB.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Andersen CL, Jensen JL, Orntoft TF. Normalization of real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR data: a model-based variance estimation approach to identify genes suited for normalization, applied to bladder and colon cancer data sets. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5245–5250. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandle JE, Telmer PG. Steviol glycoside biosynthesis. Phytochem. 2007;68:1855–1863. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin S, Beaulieu JF, Huggett J, Jaggi R, Kibenge FSB, Olsvik PA, Penning LC, Toegel S. MIQE précis: practical implementation of minimum standard guidelines for fluorescence-based quantitative real-time PCR experiments. BMC Mol Biol. 2010;11:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-11-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceunen S, Geuns JMC. Steviol glycosides: chemical diversity, metabolism, and function. J Nat Prod. 2013;76:1201–1228. doi: 10.1021/np400203b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang E, Shi S, Liu J, Cheng T, Xue L, Yang X, Yang W, Lan Q, Jiang Z. Selection of reference genes for quantitative gene expression studies in Platycladus orientalis (cupressaceae) using real-time PCR. PLoS ONE. 2012 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Hou K, Qin P, Liu H, Yi B, Yang W, Wu W. RNA-Seq for gene identification and transcript profiling of three Stevia rebaudiana genotypes. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:571. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Li X, Wang D, Li L, Zhou H, Liu Z, Wu J, Wang P, Jiang X, Fabrice MR, Zhang S, Wu J. Identification and testing of reference genes for gene expression analysis in pollen of Pyrus bretschneideri. Sci Hortic (Amsterdam) 2015;190:43–56. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2015.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cordoba E, Salmi M, León P. Unraveling the regulatory mechanisms that modulate the MEP pathway in higher plants. J Exp Bot. 2009;60:2933–2943. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czechowski T, Stitt M, Altmann T, Udvardi MK. Genome-wide identification and testing of superior reference genes for transcript normalization. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:5–17. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.063743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derveaux S, Vandesompele J, Hellemans J. How to do successful gene expression analysis using real-time PCR. Methods. 2010;50:227–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djilianov D, Genova G, Parvanova D, Zapryanova N, Konstantinova T, Atanassov A. In vitro culture of the resurrection plant Haberlea rhodopensis. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2005;80:115–118. doi: 10.1007/s11240-004-8835-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duhoux A, Délye C. Reference genes to study herbicide stress response in Lolium sp.: up-regulation of P450 genes in plants resistant to acetoacetate-synthase inhibitors. PLoS ONE. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan C, Ma J, Guo Q, Li X, Wang H, Lu M. Selection of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR in bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) PLoS ONE. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli V, Messias RS, Silva SDA, Rombaldi CV. Selection of reliable reference genes for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction studies in maize grains. Plant Cell Rep. 2013;32:1869–1877. doi: 10.1007/s00299-013-1499-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli V, Borowski JM, Perin EC, Messias Rda S, Labonde J, Pereira Idos S, Silva SD, Rombaldi CV. Validation of reference genes for accurate normalization of gene expression for real time-quantitative PCR in strawberry fruits using different cultivars and osmotic stresses. Gene. 2015;554:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giri CC, Zaheer M. Chemical elicitors versus secondary metabolite production in vitro using plant cell, tissue and organ cultures: recent trends and a sky eye view appraisal. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2016;126:1–18. doi: 10.1007/s11240-016-0985-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Ling H, Wu Q, Xu L, Que Y. The choice of reference genes for assessing gene expression in sugarcane under salinity and drought stresses. Sci Rep. 2014;4:7042. doi: 10.1038/srep07042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajihashemi S, Geuns JMC. Gene transcription and steviol glycoside accumulation in under polyethylene glycol-induced drought stress in greenhouse cultivation. FEBS Open Bio. 2016;6(9):937–944. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajihashemi S, Geuns JMC, Ehsanpour AA. Gene transcription of steviol glycoside biosynthesis in Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni under polyethylene glycol, paclobutrazol and gibberellic acid treatments in vitro. Acta Physiol Plant. 2013;35:2009–2014. doi: 10.1007/s11738-013-1226-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hellemans J, Mortier G, De Paepe A, Speleman F, Vandesompele J. qBase relative quantification framework and software for management and automated analysis of real-time quantitative PCR data. Genome Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-2-r19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagland DR, Arnon DI (1950) The water-culture method for growing plants without soil. Calif Agric Exp Stn Circ 347:1-32. citeulike-article-id:9455435

- Huggett J, Dheda K, Bustin S, Zumla A. Real-time RT-PCR normalisation; strategies and considerations. Genes Immun. 2005;6:279–284. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraman S, Manoharan MS, Illanchezian S. In-vitro antimicrobial and antitumor activities of Stevia rebaudiana ( Asteraceae ) leaf extracts. Trop J Pharm Res. 2008;7:1143–1149. doi: 10.4314/tjpr.v7i4.14700. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeppesen PB, Gregersen S, Alstrup KK, Hermansen K. Stevioside induces antihyperglycaemic, insulinotropic and glucagonostatic effects in vivo: studies in the diabetic Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rats. Phytomedicine. 2002;9:9–14. doi: 10.1078/0944-7113-00081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jian B, Liu B, Bi Y, Hou W, Wu C, Han T. Validation of internal control for gene expression study in soybean by quantitative real-time PCR. BMC Mol Biol. 2008;9:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-9-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil SA, Kamal N, Sajid M, Ahmad N, Zamir R, Ahmad N, Ali S. Synergism of polyamines and plant growth regulators enhanced morphogenesis, stevioside content, and production of commercially important natural antioxidants in Stevia rebaudiana. Bert Vitr Cell Dev Biol Plant. 2016;52:74–184. doi: 10.1007/s11626-016-0054-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BR, Nam HY, Kim S, Kim S, Chang Y. Normalization of reverse transcription quantitative-PCR with housekeeping genes in rice. Biotechnol Lett. 2003;25:1869–1872. doi: 10.1023/A:1026298032009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight H, Knight MR. Abiotic stress signalling pathways: specificity and cross-talk. Trends Plant Sci. 2001;6:262–267. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(01)01946-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar H, Kaul K, Bajpai-Gupta S, Kaul VK, Kumar S. A comprehensive analysis of fifteen genes of steviol glycosides biosynthesis pathway in Stevia rebaudiana (Bertoni) Gene. 2012;492:276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JM, Roche JR, Donaghy DJ, Thrush A, Sathish P. Validation of reference genes for quantitative RT-PCR studies of gene expression in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) BMC Mol Biol. 2010;11:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-11-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemus-Mondaca R, Vega-Gálvez A, Zura-Bravo L, Ah-Hen K. Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni source of a high-potency natural sweetener: a comprehensive review on the biochemical, nutritional and functional aspects. Food Chem. 2012;132:1121–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.11.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li QF, Sun SSM, Yuan DY, Yu H, Gu M, Liu Q. Validation of candidate reference genes for the accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data in rice during seed development. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 2009;28:49–57. doi: 10.1007/s11105-009-0124-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ling H, Wu Q, Guo J, Xu L, Que Y. Comprehensive selection of reference genes for gene expression normalization in sugarcane by real time quantitative RT-PCR. PLoS ONE. 2014 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JH, Kitashiba H, Wang J, Ban Y, Takaya Moriguchi T. Polyamines and their ability to provide environmental stress tolerance to plants. Plant Biotechnol. 2007;24:117–126. doi: 10.5511/plantbiotechnology.24.117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loc NH, Giang NT, Huy ND. Effect of salicylic acid on expression level of genes related with isoprenoid pathway in centella (Centella asiatica (L.) Urban) cells. 3. Biotech. 2016;6:86. doi: 10.1007/s13205-016-0404-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucho SR, Amaral MN, Milech C, Ferrer MA, Antonio Asensio Calderón AA, Bianchi VJ, Braga EJB. Elicitor-induced transcriptional changes of genes of the steviol glycosides biosynthesis pathway in Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni. J Plant Growth Regul. 2018;37:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s00344-018-9795-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madan S, Ahmad S, Singh GN, Kohli K, Kumar Y, Singh R, Garg M. Stevia rebaudiana (Bert.) Bertoni—a review. Indian J Nat Prod Resour. 2010;1:267–286. [Google Scholar]

- Mallona I, Lischewski S, Weiss J, Hause B, Egea-Cortines M. Validation of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR during leaf and flower development in Petunia hybrida. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melis MS. Chronic administration of aqueous extract of Stevia rebaudiana in rats: renal effects. J Ethnopharmacol. 1995;47:129–134. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(95)01271-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melis MS, Sainati AR. Effect of calcium and verapamil on renal function of rats during treatment with stevioside. J Ethnopharmacol. 1991;33:257–262. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(91)90086-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modi A, Litoriya N, Prajapati V, Rafalia R, Narayanan S. Transcriptional profiling of genes involved in steviol glycoside biosynthesis in Stevia rebaudiana bertoni during plant hardening. Dev Dyn. 2014;243:1067–1073. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.24157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraes GP, Benitez LC, do Amaral MN, Vighi IL, Auler PA, da Maia LC, Bianchi VJ, Braga EJB. Evaluation of reference genes for RT-qPCR studies in the leaves of rice seedlings under salt stress. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14:2384–2398. doi: 10.4238/2015.March.27.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15:473–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW, Tichopad A, Prgomet C, Neuvians TP. Determination of stable housekeeping genes, differentially regulated target genes and sample integrity: bestkeeper–excel-based tool using pair-wise correlations. Biotechnol Lett. 2004;26:509–515. doi: 10.1023/B:BILE.0000019559.84305.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radoni A, Thulke S, Mackay IM, Landt O, Siegert W, Nitsche A. Guideline to reference gene selection for quantitative real-time PCR. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;313:856–862. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen R. Quantification on the LightCycler. Rapid Cycle Real Time PCR Methods Appl. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Reddy DS, Bhatnagar-Mathur P, Reddy PS, Cindhurim KS, Ganesh AS, Sharma KK. Identification and validation of reference genes and their impact on normalized gene expression studies across cultivated and wild Cicer species. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:1–19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid KE, Olsson N, Schlosser J, Peng F, Lund ST. An optimized grapevine RNA isolation procedure and statistical determination of reference genes for real-time RT-PCR during berry development. BMC Plant Biol. 2006;6:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-6-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickes LN, Klumb EK, Benitez LC, Braga EJB, Bianchi VJ. Stable reference genes for studies of gene expression in Prunus persica under water stress. Aust J Crop Sci. 2016;10:1348–1356. doi: 10.21475/ajcs.2016.10.09.p7864. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues-Brandão I, Kleinowski AM, Einhardt AM, Lima MC, Amarante L, Peters JA, Braga EJB. Salicylic acid on antioxidant activity and betacyan in production from leaves of Alternanthera tenella. Ciênc Rural. 2014;44:1893–1898. doi: 10.1590/0103-8478cr20130873. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silver N, Best S, Jiang J, Thein SL. Selection of housekeeping genes for gene expression studies in human reticulocytes using real-time PCR. BMC Mol Biol. 2006;7:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-7-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh G, Singh G, Singh P, Parmar R, Paul N, Vashist R, Swarnkar MK, Kumar A, Singh S, Singh AK, Kumar S, Sharm RM. Molecular dissection of transcriptional reprogramming of steviol glycosides synthesis in leaf tissue during developmental phase transitions in Stevia rebaudiana Bert. Sci Rep. 2017;7:11835. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12025-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stajner N, Cregeen S, Javornik B. Evaluation of reference genes for RT-qPCR expression studies in hop (Humulus lupulus L.) during infection with vascular pathogen Verticillium albo-atrum. PLoS ONE. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadhani MB, Patel VH, Subhash R. In vitro antioxidant activities of Stevia rebaudiana leaves and callus. J Food Compos Anal. 2007;20:323–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2006.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vandesompele J, Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van Roy N, De Paepe A, Speleman F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang QJ, Zheng LP, Sima YH, Yuan HY, Wang JW. Methyl jasmonate stimulates 20-hydroxyecdysone production in cell suspension cultures of Achyranthes bidentate. Plant Omics. 2013;6:116–120. [Google Scholar]

- Wei L, Miao H, Zhao R, Han X, Tide Z, Haiyang Z. Identification and testing of reference genes for Sesame gene expression analysis by quantitative real-time PCR. Planta. 2013;237:873–889. doi: 10.1007/s00425-012-1805-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolwer-Rieck The leaves of Stevia rebaudiana (Bertoni), their constituents and the analyses thereof: a review. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:886–895. doi: 10.1021/jf2044907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie F, Xiao P, Chen D, Xu L, Zhang B. miRDeepFinder: a miRNA analysis tool for deep sequencing of plant small RNAs. Plant Mol Biol. 2012;80:75–84. doi: 10.1007/s11103-012-9885-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Zhu X, Gong Y, Xu L, Wang Y, Liu L. Evaluation of reference genes for gene expression studies in radish (Raphanus sativus L.) using quantitative real-time PCR. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;424:398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.06.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T, Peng H, Whitaker BD, Jurick WM. Differential expression of calcium/calmodulin-regulated SlSRs in response to abiotic and biotic stresses in tomato fruit. Physiol Plant. 2013;148:445–455. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi S, Qian Y, Han L, Sun Z, Fan C, Liu J, Ju G. Selection of reliable reference genes for gene expression studies in Rhododendron micranthum Turcz. Sci Hortic (Amsterdam) 2012;138:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2012.02.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Davis LC, Verpoorte R. Elicitor signal transduction leading to production of plant secondary metabolites. Biotechnol Adv. 2005;23:283–333. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 1 Specificity of reference genes for Stevia rebaudiana under the effect of elicitors agents (methyl jasmonate, salicylic acid, and spermidine) (TIFF 1526 kb)