Abstract

Background

Recently a hyperthermic rat hippocampal slice model system has been used to investigate febrile seizure pathophysiology. Our previous data indicates that heating immature rat hippocampal slices from 34 to 41°C in an interface chamber induced epileptiform-like population spikes accompanied by a spreading depression (SD). This may serve as an in vitro model of febrile seizures.

Results

In this study, we further investigate cellular mechanisms of hyperthermia-induced initial population spike activity. We hypothesized that GABAA receptor-mediated 30–100 Hz γ oscillations underlie some aspects of the hyperthermic population spike activity. In 24 rat hippocampal slices, the hyperthermic population spike activity occurred at an average frequency of 45.9 ± 14.9 Hz (Mean ± SE, range = 21–79 Hz, n = 24), which does not differ significantly from the frequency of post-tetanic γ oscillations (47.1 ± 14.9 Hz, n = 34) in the same system. High intensity tetanic stimulation induces hippocampal neuronal discharges followed by a slow SD that has the magnitude and time course of the SD, which resembles hyperthermic responses. Both post-tetanic γ oscillations and hyperthermic population spike activity can be blocked completely by a specific GABAA receptor blocker, bicuculline (5–20 μM). Bath-apply kynurenic acid (7 mM) blocks synaptic transmission, but fails to prevent hyperthermic population spikes, while intracellular diffusion of QX-314 (30 mM) abolishes spikes and produces a smooth depolarization in intracellular recording.

Conclusion

These results suggest that the GABAA receptor-governed γ oscillations underlie the hyperthermic population spike activity in immature hippocampal slices.

Background

Febrile seizures are the most prevalent type of seizures experienced by children, affecting up to 5% of the world's population [1]. Although most febrile seizures are benign and do not require treatment, they are distressing to parents, and in a few circumstances, can increase the risk of subsequent epilepsy [2]. In clinical practice, therapy for febrile seizures presently is unsatisfactory, since clinical data are insufficient to document efficacy of most anti-epileptic drugs [3]. The most commonly used drug, phenobarbital, has significant deleterious effects on learning and behavior.

A better understanding of the underlying mechanisms of febrile seizures might lead to new strategies of prevention or treatment [4]. Recent work has identified several genes associated with familial febrile seizure tendencies [5-7]. Some of these genes code for ion channels that govern excitability of nerve tissue. We recently published a study of the characteristic hyperthermic responses represented as epileptiform-like population spike activity accompanied by spreading depression (SD) in a rat hippocampal slice, which may serve as an in vitro model of febrile seizures [8]. The hyperthermic response was age-dependent, occurring almost exclusively in young, but not newborn, rats. The primary underlying abnormality in this model was inability of neuronal tissue properly to regulate extracellular potassium concentrations. During heating of the slice, extracellular potassium concentrations rose transiently from the normal 5 mM to as high as 40 mM and extracellular field potential shitted about 20 mV negative, a reversible condition known as SD. During the early phases of SD, neurons burst synchronously in a pattern analogous to seizures. Since hyperthermic epileptiform-like population bursts exhibited the frequency of γ oscillations (30–100 Hz), we hypothesized that GABAA receptor-governed γ oscillations might underlie the cellular basis of hyperthermic epileptiform-like population spike activity.

The γ frequency oscillations (30–100 Hz) are characteristic of responses to sensory input measured by cortical EEG [9]. In the hippocampal slice preparation, γ oscillations can be evoked by brief, high frequency tetanic stimuli to region CA1 [10-13]. The extracellular field potential response during these oscillations takes the form of a train of population spikes in stratum pyramidal at γ and β (15–30 Hz) frequencies [14]. Intracellular recordings during γ oscillations induced by tetanic stimulation reveal a slow membrane depolarization in conjunction with GABAA receptor-mediated inhibitory postsynaptic potentials [11,15]. This synaptic inhibition-based γ activity entrains action potential generation in pyramidal neurons, leading to the population spikes at γ band frequencies. The specific GABAA receptor antagonist, bicuculline, blocks the γ oscillations [14,16], an action that can be modeled by simulated neuronal networks [17]. The γ band oscillations appear to play an important role in generation of ictal epileptiform activity in hippocampal slices [18]. This study explores the role of γ oscillations in epileptiform activity in the hyperthermic rat hippocampal slice.

Results

Hyperthermia-induced epileptiform-like population spike activity

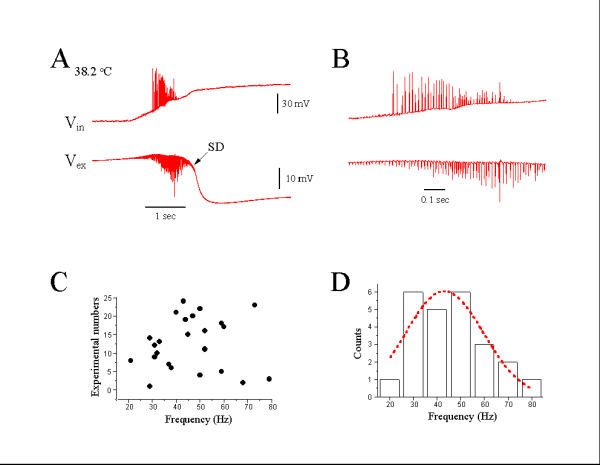

More than 90% of slices heated to 40°C showed a "febrile-seizure like event," represented as initial epileptiform-like population bursts, followed by SDs. Figure 1A shows a typical "febrile seizure-like event" elicited by heating a hippocampal slice from 33.9 to 38.2°C. The epileptiform discharges demonstrated a frequency of 80 Hz (Fig. 1B), within the 30–100 Hz γ oscillation range. Summary of data from 24 slices showed that 71% (17/24) of hyperthermic epileptiform-like population spike activity fired at a frequency range between 30–50 Hz (Fig. 1C,D), with a mean oscillation frequency of 45.9 ± 3.0 (mean ± SE, n = 24).

Figure 1.

Hyperthermia-induced γ oscillation. (A): Heating hippocampal slice to 38.2°C induced epileptiform-like spikes, followed by a slow spreading depression (SD) recorded by intracellular (Vin) and extracellular (Vex) electrodes simultaneously. (B): Expanded time scale from (A) to show initial epileptiform-like spikes. (C): Distribution of frequency of initial epileptiform spikes in 24 experimental cases. (D): Gaussian-fitting shows a γ band frequency (30–80 Hz) distribution of hyperthermia-induced epileptiform spikes.

Comparison of post-tetanic γ oscillation and hyperthermic population spike activity

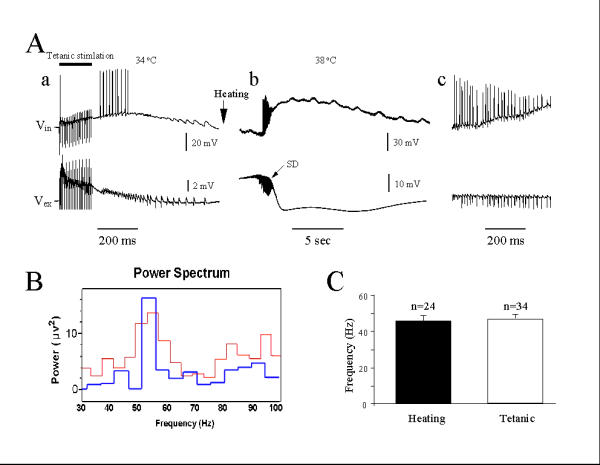

Figure 2 shows the comparison between hyperthermic population spike activity and post-tetanic γ oscillations. In standard artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF), a tetanic stimulation at 100 Hz, 100 μsec, 2 mA, for 200 ms (20 trains) elicited γ and β frequency population spikes, visible both with intracellular and extracellular recordings. In the same slice, heating to 38°C (2Ab) evoked population oscillation very similar to those of post-tetanic γ oscillations. Power spectrum analysis of the population of responses among all slices, showed similar frequency peak of hyperthermic and post-tetanic gamma oscillations (Fig. 2B). Among all slices, hyperthermic oscillations occurred at a frequency of 45.9 ± 3.0 Hz (mean ± SE, n = 24) and post-tetanic gamma oscillations at 47.1 ± 2.6 (mean ± SE, n = 34). These two frequencies do not significantly differ (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Comparison of hyperthermic and post-tetanic γ oscillations. (A): a. Post-tetanic stimulation (100 Hz, 20 trains, 2 mA, 100 μs) induced γ oscillation at 34°C. b. Heating the same recorded slice to 38°C induced an initial γ oscillation accompanied by a slow SD. c. Expanded time scale shows the similar frequency ranges of post-tetanic and hyperthermic oscillations. (B): Comparison of frequency power by power spectrum analysis between Aa and Ab. (C) There is no significant difference of average frequency between post-tetanic and hyperthermic oscillations.

Effects of high intensity tetanic stimulation

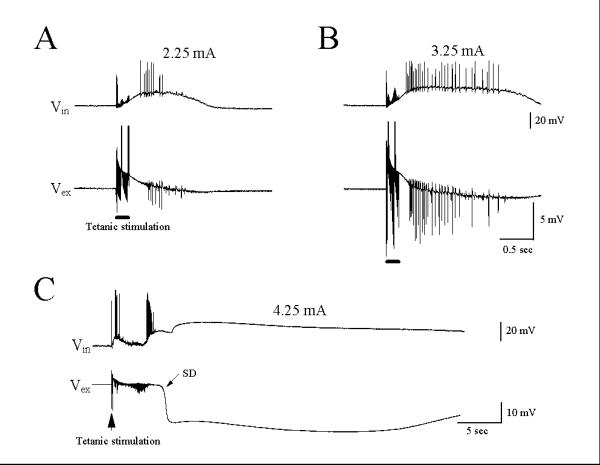

Results from this and our previous study showed that the SD always followed hyperthermic bursts [8], but tetanic stimulation induced only γ oscillations in the absence of SD (Fig. 2). Therefore, we investigated whether high-intensity tetanic stimulation could induce γ oscillations followed by SD. Fig. 3A illustrates a weak γ oscillation of field potential in response to tetanic stimulation at 2.25 mA. Tetanic stimulation at 3.25 mA induced a strong γ oscillation with a large field burst amplitude and long-lasting depolarization (Fig. 3B). In 6 of 7 tested slices, tetanic stimulation at 4.25 mA induced, not only prominent γ oscillations, but also SDs (Fig. 3C). These post-tetanic depolarizations had duration and time course very similar to those of hyperthermic SDs (Fig. 1A,2Ab).

Figure 3.

Post-tetanic stimulation at high intensity induced γ oscillations followed by a slow SD. (A): Post-tetanic stimulation at 2.25 mA elicited a rudimentary γ oscillation. (B): Post-tetanic stimulation at 3.25 mA induced a typical γ oscillation with large amplitude and long duration. (C): Post-tetanic stimulation at 4.25 mA induced a γ oscillation followed by a slow SD. Traces A-C are recorded from the same slice, which is a typical representative of five experiments.

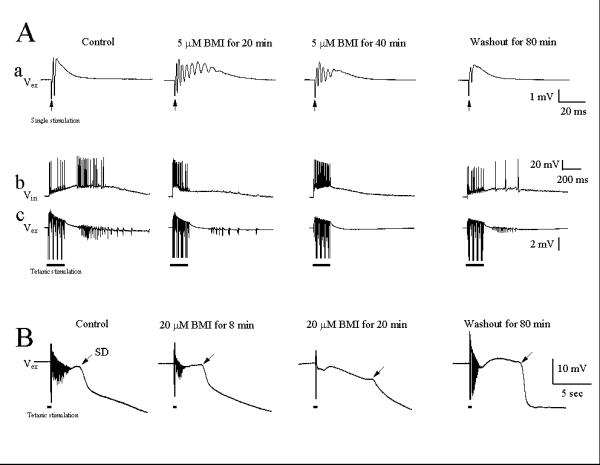

Effects of bicuculline

We utilized the specific GABAA receptor antagonist, bicuculline methiodide (BMI), to ascertain whether γ oscillations were dependent upon GABAergic mechanisms. The effect of BMI on the field potential in region CA1 is shown in Fig. 4. Bath-applied BMI (5 μM) changed the single evoked population spike to multiple spikes, in a reversible manner. In the same slice, tetanic stimulation delivered in control artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) induced typical γ oscillations, and these γ oscillations were abolished by addition of BMI to the perfusate. γ oscillations recovered partially by 80 minutes of wash in ACSF. Figure 4B shows another case in which high intensity of tetanic stimulation was applied to elicit γ oscillations and SDs. Addition of 20 μM BMI reversibly blocked γ oscillations, but not the SD.

Figure 4.

The GABAA receptor antagonist, bicuculline (BMI), blocks post-tetanic γ oscillations. (A): a. BMI (5 μM) induced multiple field potential spikes to a single stimulation, b and c. BMI reversibly blocked post-tetanic γ oscillations. (B) BMI (20 μM) blocked high intensity (4 mA) tetanic stimulation-induced γ oscillation, but not the slow SD. The traces in (A) were recorded from the same neuron (n = 6 experiments) and in (B) from another neuron (n = 4 experiments).

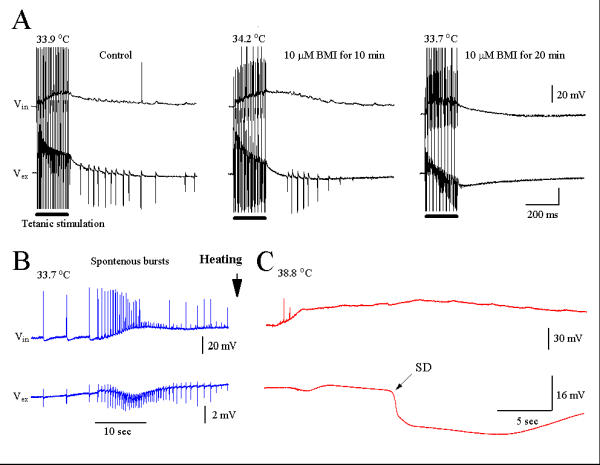

In a second set of experiments using five slices (Fig. 5), we examined the effects of BMI on hyperthermic epileptiform-like population bursts. Bath-application of 10 μM BMI for 20 min abolished post-tetanic γ oscillations. After several minutes of exposure to BMI, slices demonstrated rhythmic spontaneous bursts of population spikes (Fig. 5B), indicating that GABAA receptors have been blocked by BMI. Under these conditions, heating of the slice only evoked the SD without the initial population spikes (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

(A): BMI (10 μM) blocked post-tetanic γ oscillations. (B): Persistence of spontaneous spikes and bursts after BMI block of γ oscillation. (C): In the presence of BMI, heating the slice to 38.8°C induced a slow SD without initial γ oscillations. Traces A-C were recorded from the same neuron (n = 6 experiments).

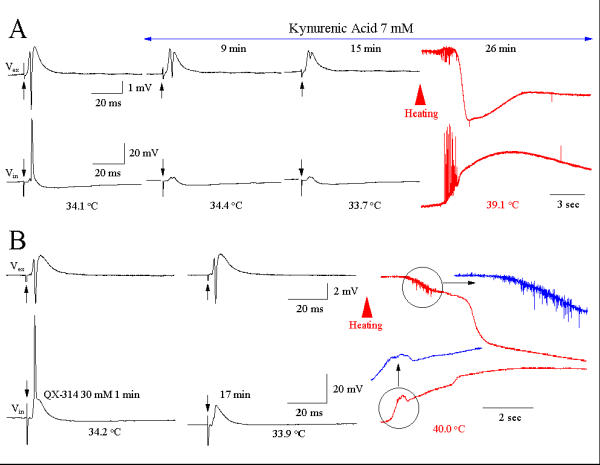

Effects of kynurenic acid and QX 314

Figure 6A shows the effect of the ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonist, kynurenic acid (Kyn-A, 7 mM), on γ oscillations. Kyn-A dramatically attenuated evoked synaptic transmission, but failed to prevent hyperthermia-induced γ oscillations and slow SDs, suggesting that excitatory synaptic transmission is not necessary for hyperthermic γ oscillations and SDs. In Fig. 6B, 30 mM QX-314 was incorporated into the recording electrode. The action potentials were blocked by intracellular QX-313 diffusion. Heating the slice to 37°C elicited a γ oscillation followed by a slow SD in the extracellular field recording. However, the intracellularly-recorded hyperthermic γ oscillation disappeared and was replaced by a smooth depolarization (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

(A): Kynurenic acid (Kyn, 7 mM) blocked evoked synaptic transmission, but failed to prevent γ oscillations and SDs elicited by heating the slice. Traces illustrate four slice recordings. (B): QX-314 blocks hyperthermia-induced γ oscillation in the intracellular recording from three slices.

Discussion

This study suggests that GABAA receptor-governed γ oscillations underlie the hyperthermic population spike activity in immature hippocampal slices.

Gamma oscillations underlie hyperthermic epileptiform-like population spikes

Gamma oscillations are defined as coherent cortical oscillations at γ (30–100 Hz) band frequency frequencies in in vivo and in vitro models. In hippocampal slice preparations, γ oscillations can be triggered by high frequency tetanic stimuli, called post-tetanic γ oscillations [10-13]. In addition to post-tetanic γ oscillations, the γ oscillations also can be elicited by metabotropic glutamate receptor agonists, carbacol, or free extracellular Mg2+[18,19]. In this study, we report that γ oscillations can occur in a model of a clinical disorder, namely hyperthermia. Hyperthermic epileptiform-like population spikes occur within the band of γ frequencies (30–100 Hz). Post-tetanic γ oscillations can be mimicked by hyperthermic stimulation in the same slice. Tetanic stimulation at high intensity induces initial γ oscillations followed by a slow SD which resembles hyperthermic epileptiform-like population spikes followed by a slow SD. Finally, both post-tetanic γ oscillations and hyperthermic epileptiform-like population spikes were completely blocked by a GABAA receptor antagonist, BMI. This experimental evidence suggests that the GABAA receptor-governed γ oscillations underlie the hyperthermic population spikes in our in vitro model system.

Possible mechanisms of hyperthermic γ oscillation

Accumulating lines of evidence demonstrate that the genesis mechanisms for post-tetanic γ oscillations involve slow GABAA receptor-mediated depolarization, extracellular K+ elevation and field effects [10-13]. The present study showed that these three major factors also underlie hyperthermic γ oscillations. As shown in Fig. 1A and 2A, the hyperthermic γ oscillations always overlie the slow membrane depolarizations. For post-tetanic γ oscillations, the slow depolarizations were mediated by tetanic stimulation-induced GABAergic depolarizing action [20-23]. This GABAergic depolarization is attributed to the tetanic stimulation-induced accumulation of intracellular chloride [24] and extracellular potassium [22]. For hyperthermic γ oscillations, heating causes a Na+/K+ pump failure [8], in turn resulting in the accumulation of intracellular Na+ and Cl-, as well as extracellular K+, finally causing a slow membrane depolarization. In our previous report, the extracellular K+ indeed elevated dramatically during hyperthermia-induced epileptiform-like population spikes and SDs [8]. Field effects further contribute to post-tetanic γ oscillations [25,26]. High Frequency tetanic stimuli leads to cellular swelling [27,28], increasing extracellular resistance. According to Ohm's law, this increases the voltage deflection recorded for a given current flowing through this extracellular resistance. Current generated by the active population travels through the resistances of the extracellular space and of the nearby inactive cells, therefore producing the extracellular population spikes and meanwhile depolarizing the inactive cells. In this manner, inactive cells are brought closer to threshold, enhancing their opportunity to firing together [29-31]. The extracellular resistance is the major determinant of field-effect strength [32]. Since the extracellular volume fraction in CA1 stradium pyramidal is only 12% compared with approximately 18% in CA3 and granule cells [33], the CA1 pyramidal cells are particularly susceptible to field effects. The accumulation of extracellular K+ during hyperthermic SDs depolarizes membrane potential, which triggers initial γ oscillations. Cell swelling reduces the extracellular space, which triggers slow SDs [8], (Fig. 1A and 2A). In Fig. 6A, after blockade of synaptic transmission by kynurenic acid (7 mM), heating the slice still induced γ-oscillation followed by SD, suggesting that a non-synaptic mechanism (local field effect) may be involved in the generation of hyperthermic γ-oscillations and SDs. Figure 6B demonstrated that hyperthermic γ-oscillations disappear in the presence of an intracellularly delivered Na+ channel blocker (QX 314, 30 mM).

Gamma oscillations and seizures

Epileptic activity can result from an imbalance between glutamatergic excitation and GABAergic inhibition. However, this simple balance model has been challenged by findings that GABAergic transmission remains effective in some epilepsy models, in epileptogenic human tissue [34-40], and by current findings of the excitatory effects of GABA [18,22,23]. Therefore, the GABA excitatory effects may work as a possible ictogenic mechanism under some special condition such as tetanic stimulation. Indeed, recently Köhling et al. reported that under epileptogenic condition (free Mg 2+ in ACSF), γ band oscillations arise from GABAergic depolarizations and that this activity may lead to the generation of ictal discharges [18]. It has been reported that prolonged periods of γ oscillations are associated with temporal lobe seizures in in vivo rats [41]. Furthermore, human EEG studies with subdural recording electodes showed that a γ band oscillation could be recorded at the start of typical seizure activity [42]. In this respect, the hyperthermic γ oscillations may also play a critical role in generation of neuronal epileptiform activity. The extent to which the hyperthermic slice serves as a model of febrile seizures remains to be determined. If γ oscillations do prove to be important in clinical febrile seizures, then future work might profitably examine the therapeutic potential of mild disinhibition to disrupt inhibitory GABA-mediated synchrony at the start of ictal activity.

Conclusions

In the in vitro hippocampal slice preparation, hyperthermia-induced epileptiform-like population spikes are at γ band frequencies, and can be blocked by BMI. Therefore, the GABAA receptor-governed γ oscillations underlie the hyperthermic population spikes in immature hippocampal slices.

Materials and methods

Experiments were performed on transverse hippocampal slices prepared from Sprague-Dawley rats, ages 17 to 29 days. Rats were anesthetized with halothane and decapitated. The brain tissue was removed rapidly and placed in iced artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF). Brain tissue was then glued to a cryotome, and a few 450–500 μ transverse slices were cut through the hippocampal formations. Slices were allowed to incubate and recover for at least an hour in room temperature ACSF comprised of the following composition (mM): NaCl 117; KCl 5.4; NaHCO3 26; MgSO4 1.3; NaH2PO4 1.2; CaCl2 2.5; glucose 10, continuously bubbled with 95% O2 plus 5% CO2.

Slice were transferred one at a time to the recording chamber (FST, air-liquid interface chamber), and suspended on nylon net at the interface. Carbogen (95% O2 plus 5% CO2) was bubbled across the upper surface of the slice. Temperature was regulated by a feedback circuit, accurate to 0.5 ± 0.2°C. Baseline temperature was 34°C. After verification of evoked population spike stability for three consecutive stimuli over a time course of 15–30 minutes, bath temperature set-point was increased to 41°C and notation was made of actual temperature measured by a thermistor probe.

Extracellular field potentials were recorded with a borosilicate glass micropipette pulled to a tip diameter of 1 μ, filled with 2 M sodium chloride and with resistance approximately 1–10 MΩ. Intracellular recordings were performed with a pulled-glass fine tip micropipette (< 1 μ), with resistance approximately 80–110 MΩ, filled with 4 M potassium acetate. Hyperthermic spreading depressions (SDs) were considered to have occurred when all of the following conditions were met: 1. At least 10 mV extracellular negativity; 2. Duration of extracellular negativity at the half-height of at least 10 seconds; 3. Loss of evoked field in CA1; and recovery of field to at least 50% of control amplitude within 30 minutes of cooling to baseline temperature. Electrophysiological data were stored on a computer (Axon scope), and played back on a laser printer. Slow potentials, including extracellular field during SD also were recorded on a continuous rectilinear chart recorder. To measure oscillation frequency, we chose a slice oscillation range beginning at 200 ms, then used the "frequency count" function of the Origin program to get average frequency from each slice. Chemicals used in the experiment consisted of bicuculline methiodide (BMI), kynurenic acid (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and QX-314 (Tocris). All animal experiments were in accord with Institutional animal welfare committee guidelines.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

All authors were supported by the Marjorie Newsome and Sandra Solheim Aiken Funds for Epilepsy and the Womens' Board of the Barrow Neurological Institute. RSF was supported by the Maslah Saul Chair and the James and Carrie Anderson Laboratory fund for epilepsy research.

Contributor Information

Jie Wu, Email: jwu2@chw.edu.

Sam P Javedan, Email: Lsjavedan@hotmail.com.

Kevin Ellsworth, Email: Kevine@imapz.asu.edu.

Kris Smith, Email: Ksmith6@chw.edu.

Robert S Fisher, Email: rfisher@stanford.edu.

References

- Farwell JR, Blackner G, Sulzbacher S, Adelman L, Voeller M. First febrile seizures. Characteristics of the child, the seizure, and the illness. clin Pediatr (Phila) 1994;33:263–267. doi: 10.1177/000992289403300502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poth RA, Belfer RA. Febrile seizures: a clinical review. Compr Ther. 1998;24:7–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantala H, Tarkka R, Uhari M. A meta-analytic review of the preventive treatment of recurrences of febrile seizures. J Pediatr. 1997;131:922–925. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RS, Wu J. Basic electrophysiology of febrile seizures. Febrile Seizures (Edited by Tallie Z. Baram and Shiomo Shinnar) Academic Press. 2001. pp. 231–247.

- Wallace RH, Wang DW, Singh R, Scheffer IE, George AL, Jr, Phillips HA, Saar K, Reis A, Johnson EW, Sutherland GR, Berkovic SF, Mulley JC. Febrile seizures and generalized epilepsy associated with a mutation in the Na+-channel betal subunit gene SCN1B. Nat Genet. 1998;19:366–370. doi: 10.1038/448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace RH, Berkovic SF, Howell RA, Sutherland GR, Mulley JC. Suggestion of a major gene for familial febrile convulsions mapping to 8q13-21. J Med Genet. 1996;33:308–312. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.4.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EW, Dubovsky J, Rich SS, O'Donovan CA, Orr HT, Anderson VE, Gil-Nagel A, Ahmann P, Dokken CG, Schneider DT, Weber JL. Evidence for a novel gene for familial febrile convulsions, FEB2, linked to chromosome 19p in an extended family from the Midwest. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:63–67. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Fisher RS. Hyperthermic spreading depressions in the immature rat hippocampal slice. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:1355–1360. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.3.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallon-Baudry C, Bertrand O, Peronnet F, Pernier J. Induced gamma-band activity during the delay of a visual short-term memory task in humans. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4244–4254. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-11-04244.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittington MA, Stanford IM, Colling SB, Jefferys JG, Traub RD. Spatiotemporal patterns of gamma frequency oscillations tetanically induced in the rat hippocampal slice. J Physiol (Lond) 1997;502:591–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.591bj.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracci E, Vreugdenhil M, Hack SP, Jefferys JG. On the synchronizing mechanisms of tetanically induced hippocampal oscillations. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8104–8113. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-18-08104.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doheny HC, Traub RD, Faulkner HJ, Gruzelier J, Whittington MA. Receptive field-specific habituation of tetanus-induced gamma oscillations in the hippocampus in vitro. NeuroReport. 2000;11:1–5. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200008210-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittington MA, Doheny HC, Traub RD, LeBeau FEN, Buhl EH. Differential expression of synaptic and nonsynaptic mechanisms underlying stimulus-induced gamma oscillations in vitro. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1727–1738. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01727.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner HJ, Traub RD, Whittington MA. Anaesthetic/amnesia agents disrupt beta oscillations associated with potentiation of excitatory synaptic potentials in the rat hippocampal slice. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128:1813–1825. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub RD, Whittington MA, Buhl EH, Jefferys JGR, Faulkner HJ. On the mechanisms of the γ→β shift in neuronal oscillations induced in rat hippocampal slices by titanic stimulation. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1088–1105. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-03-01088.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner HJ, Traub RD, Whittington MA. Disruption of synchronous gamma oscillations in the rat hippocampal slice: a common mechanism of anaesthetic drug action. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;125:483–492. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittington MA, Traub RD, Jefferys JG. Synchronized oscillations in interneuron networks driven by metabotropic glutamate receptor activation. Nature. 1995;373:612–615. doi: 10.1038/373612a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhling R, Vreugdenhil M, Bracci E, Jefferys JGR. Ictal epileptiform activity is facilitated by hippocampal GABAA receptor-mediated oscillations. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6820–6829. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-06820.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub RD, Whittington MA, Cooling SB, Buzsaki GB, Jefferys JGR. Analysis of g rhythms in the rat hippocampaus in vitro and in vivo. J Physiol. 1996;492:471–484. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alger BE, Nicoll RA. GABA-mediated biphasic inhibitory responses in hippocampus. Nature. 1979;281:15–317. doi: 10.1038/281315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherubini E, Gaiarsa JL, Ben-Ari Y. GABA: an excitatory transmitter in early postnatal life. Trends Neurosci. 1991;14:515–519. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90003-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaila K, Lamsa K, Smirnov S, Taira T, Voipio J. Long-lasting GABA-mediated depolarization evoked by high-frequency stimulation in pyramidal neurons of rat hippocampal slice is attributable to a network-driven, bicarbonate-dependent K+ transient. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7662–7672. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-20-07662.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taira T, Lamsa K, Kaila K. Posttetanic excitation mediated by GABAA receptors in rat CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:2213–2218. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.4.2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley KJ, Soldo BL, Proctor WR. Ionic mechanisms of neuronal excitation by inhibitory GABAA receptors. Science Wash DC. 1995;269:977–981. doi: 10.1126/science.7638623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub RD, Dudek FE, Taylor CP, Knowles WD. Stimulation of hippocampal afterdischarges synchronized by electrical interactions. Neuroscience. 1985;14:1033–1038. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90274-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber DS, Korn H. Electrical field effects: their relevance in central neural networks. Physiol Rev. 1989;69:821–863. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1989.69.3.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochman DW, Baraban SC, Owens JWM, Schwartzkroin PA. Dissociation of synchronization and excitability in furosemide blockade of epileptiform activity. Science Wash DC. 1995;270:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5233.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutschmidt KU, Stenkamp K, Buchheim K, Heinemann U, Meierkord H. Anticonvulsant actions of furosemide in vitro. Neuroscience. 1999;91:1471–1481. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(98)00700-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferys JGR, Haas HL. Synchronized bursting of CA1 hippocampal pyramidal cells in the absence of synaptic transmission. Nature Lond. 1982;300:448–450. doi: 10.1038/300448a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferys JG. Nonsynaptic modulation of neuronal activity in the brain: electric currents and extracellular ions. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:689–723. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.4.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudek FE, Obenaus A, Tasker JG. Osmolarity-induced changes in hippocampal electrogenesis: importance of nonsynaptic mechanisms. Neurosci Lett. 1990;120:267–270. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90056-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber DS, Korn H. Electrical field effects: their relevance in central neural networks. Physiol Rev. 1989;69:821–863. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1989.69.3.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBain CJ, Traynelis SF, Dingledine R. Regional variation of extracellular space in hippocampus. Science. 1990;249:674–677. doi: 10.1126/science.2382142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince DA, Wilder BJ. Control mechanisms in cortical epileptogenic foci: "surround" inhibition. Arch Neurol. 1967;16:194–202. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1967.00470200082007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elger CE, Speckman EJ. Penicillin-induced epileptic foci in the motor cortex: vertical inhibition. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1983;56:604–622. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(83)90028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tancredi V, Hwa GGC, Zona C, Brancati A, Avoli M. Low magnesium epileptogenesis in the rat hippocampal slice: electrophysiological and pharmacological features. Brain Res. 1990;511:280–290. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90173-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelson HB, Lothman EW. Ontogeny of epileptogenesis in the rat hippocampus: a study of the influence of GABAergic inhibition. Dev Brain Res. 1992;66:237–243. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(92)90085-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerhoff CHA, Domann R, Witte OW. Inhibitory mechanisms in epileptiform activity induced by low magnesium. Pflügers Arch. 1995;430:238–245. doi: 10.1007/BF00374655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esclapez M, Hirsch JC, Khazipov R, Ben-Ari Y, Bernard C. Operative GABAergic inhibition in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons in experimental epilepsy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12151–12156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhling R, Lücke A, Straub H, Speckmann EJ, Tuxhorn I, Wolf P, Pannek H, Oppel F. Spontaneous sharp waves in human neocortical slices excised from epileptic patients. Brain. 1998;121:1073–1087. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.6.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsáki G, Ponomareff GL, Bayardo F, Ruiz R, Gage FH. Neuronal activity in the subcortically denervated hippocampus: a chronic model of epilepsy. Neuroscience. 1989;28:527–538. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RS, Webber WR, Leeser RP, Arroyo S, Uematsu S. High frequency EEG activity at the start of seizures. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1992;9:441–448. doi: 10.1097/00004691-199207010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]