Abstract

Background

The synanthropic house fly, Musca domestica (Diptera: Muscidae), is a mechanical vector of pathogens (bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites), some of which cause serious diseases in humans and domestic animals. In the present study, a systematic review was done on the types and prevalence of human pathogens carried by the house fly.

Methods

Major health-related electronic databases including PubMed, PubMed Central, Google Scholar, and Science Direct were searched (Last update 31/11/2017) for relevant literature on pathogens that have been isolated from the house fly.

Results

Of the 1718 titles produced by bibliographic search, 99 were included in the review. Among the titles included, 69, 15, 3, 4, 1 and 7 described bacterial, fungi, bacteria+fungi, parasites, parasite+bacteria, and viral pathogens, respectively. Most of the house flies were captured in/around human habitation and animal farms. Pathogens were frequently isolated from body surfaces of the flies. Over 130 pathogens, predominantly bacteria (including some serious and life-threatening species) were identified from the house flies. Numerous publications also reported antimicrobial resistant bacteria and fungi isolated from house flies.

Conclusions

This review showed that house flies carry a large number of pathogens which can cause serious infections in humans and animals. More studies are needed to identify new pathogens carried by the house fly.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12889-018-5934-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Bacteria, Fungi, House fly, House fly control, Mechanical transmission, Parasites, Pathogens, Viruses

Background

The house fly, Musca domestica L. (Diptera: Muscidae), is the most common and widespread species of fly in the world. It is said to have originated from the savannahs of Central Asia and spread throughout the world, and can be found in both rural and urban areas of tropical and temperate climates [1, 2]. The house fly belongs to a group of flies often referred to as “filth flies”; the other members belong to the families Calliphoridae and Fanniidae [3]. The house fly has been in existence since the origin of human life [4] and well adapted to life in human habitations [5]. M. domestica is an eusynanthropic, endophilic species, i.e. it lives closely in association with humans and is able to complete its entire lifecycle within habitations of humans and domestic animals [6]. House flies are often found in abundance in areas of human activities such as hospitals, food markets, slaughter houses, food centers or restaurants, poultry and livestock farms where they constitute a nuisance to humans, poultry, livestock and other farm animals, and also act as potential vector of diseases [7].

The house fly is known to carry pathogens that can cause serious and life-threatening diseases in humans and animals. Over 100 pathogens including bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites (protozoans and metazoans) have been associated with the insect [8, 9]. Molecular analysis revealed that house flies carry very diverse groups of microorganisms [10]. Evidence supporting the role of the house fly in transmission of diseases are mostly circumstantial, with the strongest evidence pointing to the correlation between the rise in incidence of diarrhoea and an increase in the fly population [11–14].

The characteristics of the pathogens carried by house flies depend on the area where the insect is collected; house flies captured from the hospital environment or animal farms (where there is extensive use of antibiotics as growth promoters) commonly carry antimicrobial resistant bacteria and fungi [9, 15–20]. More so, house flies presenting in the hospital environment may also be associated with the transmission of nosocomial infections [9, 21].

House fly causes mechanical transmission of pathogens, which is the most widely recognised mechanism [22–24]. This occurs when pathogens are transmitted from one vertebrate hosts to another without amplification or development of the organism within the vector [22]. House flies usually feed and reproduce in feces, animal manure, carrion and other decaying organic substances, and thus live in intimate association with various microorganisms including human pathogens, which may stick to body surfaces of the fly. The constant back and forth movement of house flies between their breeding sites and human dwellings can lead to the transmission of pathogens to humans and animals.

Currently, there is no systematic review on the pathogens carried by the house fly. The aim of this systematic review was to identify the types and prevalence of human pathogens carried by the house fly.

Methods

For this systematic review, we did a literature search to identify scientific articles reporting pathogens (bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites) that has been isolated from the house fly (Musca domestica). The current study conforms to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [25] (Additional file 1).

Search strategy and selection criteria

Relevant studies were searched in health-related electronic databases including PubMed, PubMed Central, Google Scholar and Science Direct using the keywords: House fly OR Musca domestica OR Pathogens OR bacteria OR fungi OR parasites OR viruses.

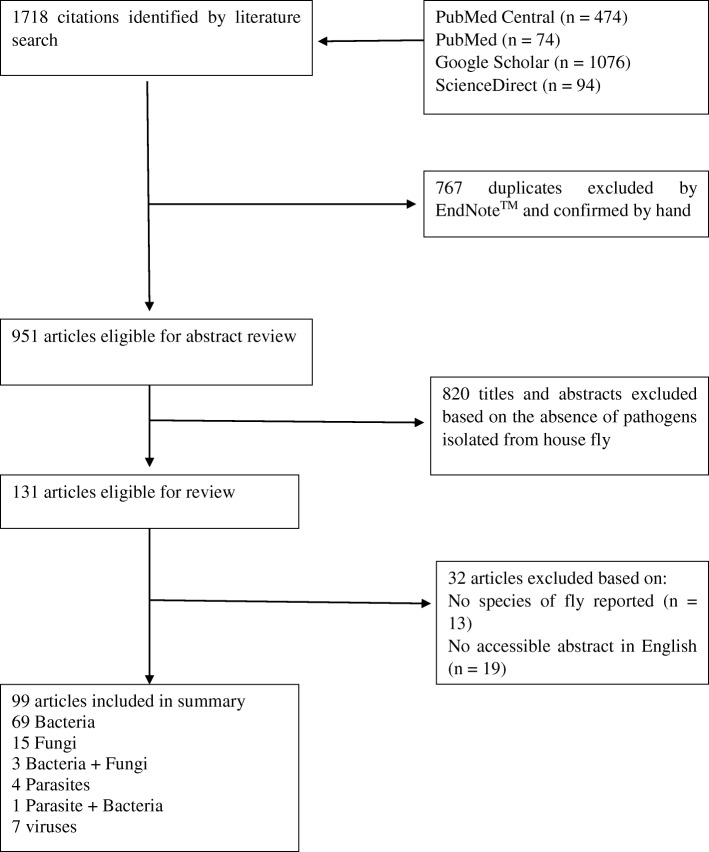

The search was limited to the studies published in English or containing at least an English abstract until November 2017. Subsequently, the titles and abstracts of the selected articles were examined by 2 reviewers, independently (parallel method) to identify articles reporting pathogens isolated from the house fly. When there was any discrepancy in their report, a third reviewer was invited to resolve the issue. Relevant papers were also manually cross checked in order to identify further references. In the selected articles, the following data were extracted by the first reviewer and checked by the second reviewer. The data included type and species of pathogen isolated, stage of house fly from which pathogen was isolated, frequency of occurrence of pathogen, method used in isolation of pathogen, type of study (field or experimental), site of the house fly from where the pathogen was isolated, nature of pathogen isolated (whether the pathogen was carrying genes that were resistant to antimicrobials or not), and location of capture of the house fly (human residents, animal farms, markets/shops, hospitals etc.). Excluded articles were those reporting pathogens isolated from flies in general without specifying the fly species. The selection process is detailed in Fig.1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the selection process for publications included in this review

Risk of bias in individual studies

Level of risk of bias for the study was likely to be high mainly because of differences in study and the methods used to isolate pathogens from the house fly. Most of the studies were not designed to isolate all the types of pathogens. Moreover, studies using molecular methods (PCR and/or sequences) yielded more pathogens compared to studies using standard cultural methods.

Results

Figure 1 (PRISMA flowchart) provides a four-phase study selection process in the present systematic review study. A total of 1718 studies were identified in the initial search. After the title and abstract screening, 131 full- text articles were retrieved. Of these, a final 99 articles were identified for this review [2–24, 26–93]

Seventy-three 73 (73.73%) of the works described bacterial pathogens (Table 1), 18 (18.18%) fungi (Table 2), 5 (5.05%) parasites (Table 3) and 7 (7.07%) described viruses. The selected studies were done in 21 countries and the study period covered the years 1970–2017. Sixty-eight of the studies were field studies (performed on house flies caught in the wild) (68.69%) while 31 were experimental studies (performed in the laboratory) (31.31%). Of the 68 field studies, 12 described pathogens isolated from house flies caught in the wild in Europe, 16 in the Middle East, 15 in Africa, 13 in USA, 10 in Asia, and 2 in South America. Twenty studies (28.88%) reported on house flies that were caught from within human habitation, 28 (28.28%) from animal farms (including poultry, dairy and piggery farms), 10 (10.10%) from the surroundings, 10 (10.10%) from food centers (including cafeteria, restaurants), 7 (7.07%) from markets or shops, 14 (14.14) from hospitals, 7 (7.07%) from dump sites or sanitary landfills while 4 (4.04%) were from gardens or farms.

Table 1.

Bacteria species that have been isolated from house flies, including the site of isolation, the frequencies and their distribution

| Bacteria genera | Species | Medical and/or veterinary importance | Geographical occurrence | Site of specimen collection | Host stage infected | Prevalence | Lab or field study | Site of isolation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helicobacter | H. pylori | Medical | Worldwide | Laboratory reared | Adult | – | Lab | External surfaces/internal organs | [70–72] |

| Campylobacter | C. jejuni | Medical and veterinary | Worldwide | Poultry, piggery | Adult/larvae | 6.2% | Field/ Lab | External surfaces/internal organs | [73, 74, 87, 90] |

| C. coli | Medical and veterinary | Worldwide | Poultry, piggery | Adult | 90.1% | Field | External surfaces/internal organs | [74] | |

| Others | Medical and veterinary | Worldwide | Restaurant, refuse dumps, barbecue shops, fruits and food vendors, markets, poultries (broiler farms) | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces/internal organs | [38, 75] | |

| Salmonella | S. typhimurium | Medical | Worldwide | Laboratory experiment | Adult | – | Lab | [37] | |

| S. enterica serovar Enteritidis | Medical | Worldwide | Poultry, dumpsters | Adult/larvae | 6–70% | Lab/field | External surfaces/internal organs | [23, 28, 39] | |

| Others | Medical | Worldwide | Restaurant, refuse dumps, barbecue shops, fruits and food vendors, markets, fish vendors, human habitation | Adult | 11.8–66.67% | Field | External surfaces/internal organs | [25, 27, 29, 70–72, 91] | |

| Escherichia | E. coli | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation, cafeteria and food centers, hospitals, open fields, poultry farms, slaughter houses, cattle farms, animal hospitals | Adult/larvae | 10.5–76.3% | Field/lab | External surfaces/internal organs | [2–24, 29–38, 40, 43–46, 48, 89, 92] |

| Bacillus | B. anthrax | Medical and veterinary | Worldwide | Laboratory reared | Adult | – | Lab | External surfaces/Internal organs | [76] |

| B. megatarium | non | Worldwide | Cafeteria and food centers | Adult | 50% | Field | External surfaces/Internal organs | [7] | |

| B. sphaericus | Medical | Worldwide | Cafeteria and food centers | Adult | 50% | Field | External surfaces/Internal organs | [7] | |

| B. cereus | Medical | Worldwide | Fresh fish | Larvae | – | Field | External surfaces/Internal organs | [46, 53] | |

| B. alvei | Medical | Worldwide | Cafeteria and food centers | Adult | 50% | Field | External surfaces/Internal organs | [7] | |

| B. pumilus | Medical | Worldwide | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces/Internal organs | [46] | ||

| B. thuringiensis | non | Worldwide | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces/Internal organs | [46] | ||

| Others | Medical | Worldwide | Dairy farms, hospitals, slaughter houses, fruit and food centers | Adult | 31.1% | Field | External surfaces | [10, 20, 44, 61, 89] | |

| Staphylococcus | S. aureus | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation, fresh fish | Adult/ larvae | 26.9% | Field | External surfaces/Internal organs | [40, 45, 53, 77, 92] |

| S. epidermidis | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces/Internal organs | [40] | |

| S. sciuri | Medical/veterinary | Worldwide | Dumpsters of restaurants | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces | [46] | |

| S. saprophyticus | Medical | Worldwide | Dumpsters of restaurants | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces | [46] | |

| S. xylosus | Medical | Worldwide | Dumpsters of restaurants | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces | [46] | |

| Others | Medical/veterinary | Worldwide | Poutry, animal farms, garden, garbage/dump areas, restaurants/cafeteria, markets, human habitation, hospitals | Adult | 22.9–28.2% | Field | External surfaces/Internal organs | [10, 20, 48, 78, 79, 89, 91] | |

| Enterococcus | E. faecalis | Medical | Worldwide | Restaurants, piggery farms | Adult | 55.5–88.2% | Field/lab | External surfaces/Internal organs | [21, 49, 50] |

| E. faecium | Medical | Worldwide | Restaurants, piggery farms | Adult | 6.8–12.8% | Field/lab | External surfaces/Internal organs | [49, 50] | |

| E. casseliflavus | Medical | Worldwide | Restaurants, piggery farms | Adult | 4.9–6.7% | Field/lab | External surfaces/Internal organs | [49, 50] | |

| E. hirae | Medical/veterinary | Worldwide | piggery farms | Adult | 12.8% | Field/lab | External surfaces/Internal organs | [50] | |

| Aeromonas | A. caviae | Medical | Worldwide | Hospitals, streets, slaughter houses (abattoir) | Adult | 39–78% | Field | Internal organs | [48, 80, 81] |

| A hydrophila | Medical | Worldwide | Open field | Adult | – | Field | Internal organs | [82] | |

| Others | Medical | Worldwide | Poutry, animal farms, garden, garbage/dump areas, restaurants/cafeteria, markets, human habitation, hospitals | Adult | – | Field | Internal organs | [79] | |

| Shigella | S. sonnei | Medical | Worldwide | Hospitals, streets, slaughter houses | Adult | – | Field | Internal organs | [48] |

| S. dysenteriae | Medical | Worldwide | Dumpsters of restaurants | Adult | – | Field | Internal organs | [46] | |

| Others | Medical | Worldwide | Poultry, animal farms, garden, garbage/dump areas, restaurants/cafeteria, markets, human habitation, hospitals | Adult | 4.8–66.67% | field | External surfaces/ internal organs | [11, 13, 29, 38, 40, 43, 79, 91] | |

| Klebsiella | K. pneumoniae | Medical | Worldwide | Hospitals, human habitation, slaughter houses | Adult | 11.3–82% | field | External surfaces/ internal organs | [15, 47, 82] |

| K. oxytoca | Medical | Open field | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces | [83] | ||

| Others | Medical | Poutry, animal farms,garden, garbage/dump areas, restaurants/cafeteria, markets, human habitation, hospitals, slaughter houses, open field | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces | [40, 44, 48, 61, 79, 89] | ||

| Pseudomonas | P. aeruginosa | Medical | Worldwide | Dump sites, slaughter houses, open field, human habitation, fresh fish, hospitals | Adult/larvae | 37% | field | External surfaces/internal organs | [15, 19, 53, 61, 84] |

| Others | Medical | Worldwide | Hospitals, streets, slaughter houses, | Adult | 21.8% | Field | External surfaces/internal organs | [44, 48, 92] | |

| Proteus | P. mirabilis | Medical | Worldwide | Slaughter houses, hospitals | Adult | 29.1% | field | External surfaces/internal organs | [15] |

| P. vulgaris | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces/internal organs | [40] | |

| Proteus sp. | Medical | Worldwide | Slaughter houses, dump sites, open fields, human habitations | Adult | 14.8% | Field | External surfaces/internal organs | [61, 89, 92] | |

| Citrobacter | C. freundi | Medical | Worldwide | Cafeteria and food centers, Slaughter houses, hospitals | Adult | 28.4% | field | External surfaces/internal organs | [7, 15] |

| Chronobacter | C. turicensis, | Medical | Worldwide | Poultry, dumpsters | Adult/larvae | 14% | Field/lab | External surfaces/internal organs | [23, 28] |

| C. universalis | Medical | Worldwide | Poultry, dumpsters | Adult/larvae | – | Field/lab | External surfaces/internal organs | [23, 28] | |

| C. sakazakii | Medical | Worldwide | Poultry, dumpsters | Adult/larvae | – | Field/lab | External surfaces/internal organs | [23, 28, 46] | |

| Listeria | L. monocytogenes | Medical | Worldwide | Poultry, dumpsters | Adult/larvae | 3–49.4% | Field/lab | External surfaces/internal organs | [23, 28, 54] |

| Others | Medical/veterinary | Worldwide | Animal farms | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces/internal organs | [78] | |

| Streptococcus | S. pyogenes | medical | Worldwide | Fresh fish, human habitation | Adult/larvae | – | Field | External surfaces/internal organs | [40, 53] |

| S. faecalis | Medical | Worldwide | Fresh fish | Larvae | – | Field | External surfaces/internal organs | [53] | |

| Others | Medical | Worldwide | Hospitals, slaughter houses, streets, dump sites, open fields, human habitation | Adult | 66.67% | Field | External surfaces/internal organs | [48, 61, 89, 91] | |

| Alternaria | Alternaria spp. | Medical | Worldwide | Fresh fish, Human habitation | Larvae | 1.4–6% | Field | [15, 53, 55] | |

| Serratia | Serratia spp. | Medical | worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | – | Field | Internal organs | [40] |

| Enterobacter | Enterobacter spp. | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | – | Field | Internal organs | [40, 89] |

| Edwardsiella | Edwardsiella spp. | Medical | Worldwide | Poultry | Adult | – | field | External surfaces/internal organs | [43] |

| Providencia | Providencia spp. | Medical | Worldwide | Poultry, animal farms, garden, garbage/dump areas, restaurants/cafeteria, markets, human habitation, hospitals, slaughter houses, open field | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces/ internal organs | [43, 79] |

| Vibrio | Vibrio cholera non O1 | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | 45.7% | Field | Internal organs | [29] |

| Others | Medical / veterinary | Worldwide | Animal farms | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces/ internal organs | [78] | |

| Morganella | M. morgana | Medical | Worldwide | Poutry, animal farms,garden, garbage/dump areas, restaurants/cafeteria, markets, human habitation, hospitals, slaughter houses, open field | Adult | 16.67% | Field | External surfaces/Internal organs | [7, 79] |

| Clostridium | Clostridium spp. | Medical | Worldwide | Dairy farms | Adult | – | Field | Internal organs | [10] |

| Corynebacterium | Corynebacterium spp. | Medical | Worldwide | Dairy farms | Adult | – | Field | Internal organs | [10] |

| Lactobacillus | Lactobacillus spp. | Medical | Worldwide | Dairy farms | Adult | – | Field | Internal organs | [10] |

| Yersinia | Y. enterocolitica | Medical | Worldwide | Hospitals, streets, slaughter houses | Adult | – | Field | Internal organs | [48] |

| Burkholderia | B. pseudomallei | Medical | Worldwide | Open field | Adult | – | Field | Internal organs | [83] |

| Acinetobacter | A. baumanni | Medical | worldwide | Poultry, dumpsters | Adult | – | Field | Internal organs | [46, 89] |

| Methylobacterium | M. persicinum | Medical | Worldwide | Poultry, dumpsters | Adult | – | Field | Internal organs | [46] |

| Micrococcus | Micrococcus sp. | Medical | Worldwide | Garbage/dump areas, poultry, restaurants | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces/Internal organs | [89] |

Table 2.

Fungi species that have been isolated from house flies, including the site of isolation, the frequencies and their distribution

| Fungi genera | Species | Medical, veterinary or agricultural importance | Geographical occurrence | Site of specimen collection | Host stage infected | Prevalence | Lab or field study | Site of isolation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cladosporum | C. cladosporoides | Medical | Worldwide | Cattles diagnosed with bovine ringworm, animal pens, dump sites | Adult/larvae | 4.7–85% | Field/lab | External surfaces | [56, 57] |

| Others | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation | Larvae | 0.2 | Field | External surfaces | [53, 55] | |

| Penicillium | P. axalicum | Medical | Worldwide | Fresh fish | Larvae | – | Field | External surfaces | [53] |

| P. corylophilum | Medical | Worldwide | Animal pens, dump sites | Larvae | – | Field | External surfaces | [57] | |

| P. fellutanum | Medical | Worldwide | Animal pens, dump sites | Larvae | 11.9% | Field | External surfaces | [57] | |

| P. verrucosum | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces | [60] | |

| P. aurantiogriseum | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces | [60] | |

| Others | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation, Cattles diagnosed with bovine ringworm, hospitals, slaughter houses | adult | 3.4–21% | Field/lab | External surfaces | [55, 56, 58, 59] | |

| Aspergillus | A. flavus | Medical | Worldwide | Animal pens, dump sites, poultry farms, dairy, piggery, slaughter houses, open field | Adult/larvae | 23.8% | Field | External surfaces | [52, 57, 60] |

| A niger | Medical | Worldwide | Animal pens, dump sites | Adult/larvae | 14.4–85.71% | Field | External surfaces | [7, 57] | |

| A fumigatus | Medical | Worldwide | Cafeteria and food centers | Adult | 85.71 | Field | External surfaces | [7] | |

| A tamari | Medical | Worldwide | Fresh fish | Larvae | – | Field | External surfaces | [53] | |

| A parasiticus | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces | [60] | |

| Others | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation, Cattles diagnosed with bovine ringworm, hospitals, slaughter houses | Adult | 2.8–67.4% | Field/lab | External surfaces | [55, 56, 58, 59] | |

| Beauveria | B. bassiana | Medical | Worldwide | Poultry farms, dairy, piggery, open field, slaughter houses | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces | [52] |

| Mucor | M. cirinelloides | Medical | Worldwide | Cafeteria and food centers | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces | [7] |

| Others | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | 2% | Field | External surfaces | [55] | |

| Alternaria | A. alternata | Medical | Worldwide | Animal pens, dump sites | Adult/larvae | 1.4–11.9% | Field | External surfaces | [53, 55, 57, 58] |

| Fusarium | F. oxysporum | Medical | Worldwide | Fresh fish | Larvae | – | Field | External surfaces | [53] |

| F. verticilliodes | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces | [60] | |

| F. proliferatum | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces | [60] | |

| Others | Medical | Worldwide | Animal pens, dump sites, Human habitation, hospitals, slaughter houses | Larvae | 4.7–17% | Field | External surfaces | [55, 57, 58] | |

| Curvularia | C. brachyspora | Medical | Worldwide | Animal pens, dump sites | Adult | 2.4% | Field | External surfaces | [57] |

| Mycelia | M. sterilia | Medical | Worldwide | Animal pens, dump sites | Adult | 2.4% | Field | External surfaces | [57] |

| Candida | C. albicans | Medical | Worldwide | Pig pen, Human habitation | Adult | 44.6% | Field | External surfaces | [51, 54] |

| C. glabrata | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | 23% | Field | External surfaces | [51] | |

| C. krusei | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | 19.6% | Field | External surfaces | [51] | |

| C. tropicalis | Medical | Worldwide | Pig pen, Human habitation | Adult | 7.4% | Field | External surfaces | [51, 54] | |

| C. dubliniensis | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | 3.6% | Field | External surfaces | [51] | |

| C. parapsilisis | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | 1.8% | Field | External surfaces | [51] | |

| Others | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | 10.5% | Field | External surfaces | [59] | |

| Microsporum | M. canis | Veterinary | Worldwide | Laboratory experiment | Adult/larvae | – | Field | External surfaces/internal organs | [85] |

| M. gypseum | Medical | Worldwide | Hospitals, slaughter houses | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces | [58] | |

| Chrysosporium | Chrysosporium spp. | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | 2% | Field | External surfaces | [55] |

| Curvalaria | Curvalaria spp. | Agricultural | Worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | 0.4% | Field | External surfaces | [55] |

| Epicoccum | Epicoccum spp. | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | 1% | Field | External surfaces | [55] |

| Eupenicillium | Eupenicillium spp. | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | 1% | Field | External surfaces | [55] |

| Moniliella | Moniliella spp. | Medical and veterinary | Worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | 9% | Field | External surfaces | [55] |

| Nigrospora | Nigrospora spp. | Agricultural | Worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | 1% | Field | External surfaces | [55] |

| Rhizopus | Rhizopus spp. | Veterinary | Worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | 2% | Field | External surfaces | [55] |

| Scopulariopsis | Scopulariopsis spp. | Veterinary | Worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | 2% | Field | External surfaces | [55] |

| Mucorales | Mucorales spp. | Medical | Worldwide | Hospitals | Adult | 11% | Field | External surfaces | [59] |

| Rhodotorula | Rhodotorula spp. | Medical/veterinary | Worldwide | Hospitals | Adult | 8.4% | Field | External surfaces | [59] |

| Moniliella | M. suaveolans | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces | [60] |

Table 3.

Parasites that have been isolated from house flies, including the site of isolation, the frequencies and their distribution

| Parasite genera | Species | Medical or veterinary importance | Geographical occurrence | Site of specimen collection | Host stage infected | Prevalence | Lab or field study | Site of isolation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascaris | A. lumbricoides | Medical | Worldwide | Slaughter houses, dump sites, human habitation, open fields | Adult | 12.6–14.29% | Field | External surfaces | [61–63, 98, 99] |

| A. suum | Veterinary | Worldwide | piggery | Adult | 62% | Field/lab | External surfaces/internal organs | [54] | |

| Entamoeba | E. histolytica | Medical | Worldwide | Slaughter houses, dump sites, human habitation, open fields | Adult | 35.43–53.57% | Field | External surfaces | [61–63] |

| Hookworm | Ancylostoma duodenale/Necator americanus | Medical | Worldwide | Slaughter houses, dump sites, human habitation, open fields | Adult | 8.93% | Field | External surfaces | [61, 62, 64] |

| Trichuris | T. trichiura | Medical | Worldwide | Slaughter houses, dump sites, human habitation, open fields, piggery | Adult | 12.5–74.0% | Field | External surfaces | [61–64] |

| T. suis | Medical/veterinary | Worldwide | Piggery | Adult | – | Field/lab | External surfaces/internal organs | [54] | |

| Strongyloides | S. stercoralis | Medical | Developing countries | Slaughter houses, dump sites, human habitation, open fields | Adult | 10.7% | Field | External surfaces/internal organs | [61] |

| S. ransomi | Veterinary | Tropical regions | Piggery | Adult | 21% | Field | External surfaces | [54] | |

| Metastrongylus | M. spp | Veterinary | Worldwide | Piggery | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces/internal organs | [54] |

| Haematopinus | H. suis | Veterinary | Worldwide | Piggery | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces/internal organs | [54] |

| Crytosporidium | C. parvum | Medical/ Veterinary | Worldwide | Laboratory experiment | Adult/larvae | – | Lab | Internal organs | [65] |

| Giardia | G. lamblia | Medical | Developing countries | Human habitation, refuse dumps, tomato/vegetable and soft drink shops | Adult | 23.62% | Field | External surfaces | [3, 63] |

| Enterobius | E. vermicularis | Medical | Worldwide but more prevalent in developed world | Poultry | Adult | – | Field | External surfaces | [3] |

| Taenia | T. spp. | Medical/veterinary | Worldwide | Human habitation, refuse dumps, tomato/vegetable and soft drink shops | Adult | 15.75% | Field | External surfaces | [63, 64] |

| Hymenolepis | H. nana | Medical | Worldwide | Human habitation, refuse dumps, tomato/vegetable and soft drink shops | Adult | 5.51% | Field | Internal organs | [63] |

Pathogens were isolated more frequently from the body surfaces of the flies as reflected from 44 studies (44.44%), followed by 33 studies (33.33%) reporting isolation from both the body surfaces and the gut, while 22 studies (22.22%) indicated isolation from the gut. Most studies reported isolation of pathogens from adult flies 91 (91.92%), followed by larvae 5 (5.05%) and from both the adults and the larvae 3 (3.03%).

The most frequent method used in the isolation of pathogens was standard cultural methods 77 (77.78%), followed by molecular methods (such as polymerase chain reaction [PCR] or sequencing) 14 (14.14%) and other parasitological techniques 8 (8.08%).

Among the bacterial pathogens isolated, 7 studies reported virulent bacteria (8.97%), 14 reported bacteria carrying genes which confer resistance to multiple antibiotics (17.95%), and the enteric bacteria were the most frequently isolated bacteria as shown in 55 studies (70.51%) (Table 1). Among the parasites, Ascaris spp. Entamoeba spp., hookworms and Trichiuris spp. were most frequently reported (Table 2). Among the fungi, Penicillum spp., Aspergillus spp., and Candida spp. were the most frequently reported (Table 3). Very few studies reported on viruses isolated from the house fly, most of which were experimental studies (Table 4).

Table 4.

Viruses that have been isolated from house flies, including the site of isolation, the frequencies and their distribution

| Virus family | Common name | Medical or veterinary importance | Geographical occurrence | Site of specimen collection | Host stage infected | Prevalence | Lab or field study | Site of isolation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Picornavirus | Senecavirus A | Medical/veterinary | Worldwide | Laboratory experiment | Adult | – | Lab | Internal organs | [65] |

| Filoviridae | Ebola virus | Medical | West and Central Africa | Laboratory experiment | Adult | – | Lab | Internal organs | [68] |

| Arteriviridae | Porcine reproductive and respirator syndrome virus | Veterinary | Worldwide | Piggery | Adult | – | Lab | Internal organs | [86] |

| Orthomyxoviridae | Avian Influenza virus H5N1 | Veterinary | Worldwide | Laboratory experiment | Adult | – | Lab | Internal organs | [66] |

| Hytrosaviridae | Musca domestica salivary gland hypertrophy virus (MdSGHV) | Veterinary | Worldwide | Laboratory experiment | Adult | 3–24% | Lab | Internal organs | [88] |

| Paramyxoviridae | Newcastle disease virus | Medical/veterinary | Worldwide | Laboratory experiment | Adult | – | Lab | Internal organs | [67] |

Discussion

This systematic review revealed a total of at least 130 pathogens that have been isolated from the house fly. Bacterial pathogens were by far the most frequently reported, suggesting the house fly may play an important role as vector of bacterial diseases. Fungi were the second most frequently isolated pathogens followed by parasites, and viruses were the least frequent. The differences in the rate of isolation of these pathogens could be attributed to individual biases at the level of the study, pertaining to the method used in the isolation of the pathogens. Most of the articles reviewed used standard cultural methods for the isolation of pathogens, which may have skewed the outcome towards bacterial pathogens; more advanced methods including cell culture and PCR, which are required for the detection of viruses, are expensive and not readily available. This may explain the low number of reports on isolation of viruses from house flies.

Pathogens were more frequently isolated from the body surfaces of house flies, especially from those captured from within human habitations and animal farms. House flies habitually feed on feces, animal manure, carrion and other decaying organic matter. In the process of feeding, pathogens stick on their mouth parts, wings, legs and other body surfaces, which they carry back to human habitations and animal farms, where they live and complete their lifecycle [6]. The constant movement of the house fly back and forth from feces (or other animal waste) to food and drinking water therefore places humans and animals at risk of infection. The frequent isolation of pathogens from the body surfaces of the flies makes it plausible that when house flies transmit pathogens, they only act as mechanical vectors [22–24, 26]. Unlike in biological transmission, there is no multiplication (amplification) of the pathogen in the host in mechanical transmission. However, the fly has been demonstrated to carry sufficient quantity of pathogens on its body surface, enough to cause an infection [27]. The quantity of pathogens present in the gut is usually higher than the quantity present on the body surfaces, suggesting that feces and vomitus may also serve as a major route of transmission of pathogens [28, 94].

Enteric bacteria were the most frequently isolated bacteria [2–24, 27, 29–35, 37–39]. This could be due to the fact that house flies feed mainly on feces and other animal waste, which is a rich source of enteric bacteria. Some of the bacteria isolated from house flies were highly virulent species including enteropathogenic strains such as enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC), enterohaemorhagic E. coli (EHEC), enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC), and enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) [18, 29–34], Vibrio cholera and Bacillus anthracis that cause enteric diseases, cholera and anthrax respectively. Others including Klebsiella spp., Pseudomonas, Staphylococci, Streptococci, Clostridium spp. and Enterococci to name just a few, are also important causes of diseases in humans (including nosocomial infection). Furthermore, several studies reported bacteria that were resistant to multiple antibiotics including E. coli (20,35,36), Klebsiella pneumoniae [15, 47] and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [15, 19, 48]. Most of the antibiotic resistant bacteria were isolated from flies caught in and around hospital environments and animal farms (where there is an extensive use of antibiotics as growth promoters) [15, 17–20, 49, 50], suggesting that house flies may also play a role in the dissemination of antibiotic resistant bacteria to different environments [17].

Fungi species frequently isolated from the house fly belonged to the genera: Candida, Aspergillus, and Penicillium [7, 51–60]. Some of these genera (including Candida and Aspergillus) contain fungi species that are important human pathogens, but most others contain fungi species that are of veterinary (e.g. Microsporum, Rhizopus, Scopularipsis and Rhodotorula) and agricultural importance (e.g. Curvalaria and Nigrospora). Furthermore, genera Epicoccum contain fungi species which are important allergens. Some species of fungi that have been isolated from the house fly were resistant to multiple antifungals, example of which includes Candida [51]. Most of the fungi that have been isolated from the house fly were reportedly isolated from the outer cuticle of the insect and rarely from internal organs, feces or vomitus.

Very few studies reported the isolation of parasites from the house fly. Among these studies, almost all the parasites described were isolated from the body surfaces of the flies. The parasites species frequently reported belonged to the genera: Ascaris, Entamoeba, Trichiuris, and the hookworms [61–64]. These parasites commonly cause enteric diseases in humans and their frequent occurrence on the house fly could also be attributed to the food source of the house fly. Parasites of the genera Metastrongylus and Heamatopinus, which are known to be strict pathogens of domestic animals including pigs were also reported [54].

Reports of the isolation of viruses from wild-caught flies are very rare. However, house flies were reported to be capable of carrying a number of viruses in laboratory experiments. The majority of these viruses were of veterinary importance including the Senecavirus A whose natural hosts are pigs and cows [65]; the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus which causes a disease of pigs called porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS), also referred to as the blue-ear pig disease; Avian influenza virus and Newcastle disease virus which cause diseases in birds including poultry [66, 67]. In addition, one study demonstrates the ability of the house fly to carry the Ebola virus in laboratory experiments [68]. However, its role in the transmission of the virus is still to be confirmed.

Study limitations

Although this systematic review addresses a key gap in the evidence base by identifying the types and prevalence of pathogens carried by the house fly, there are some key limitations in the evidence collected. Firstly, the survival of these pathogens on the house fly and the house fly’s role in the transmission of these pathogens to humans and animals remains largely undefined. Secondly, it is unclear how representative these pathogens reported are of the wider population of pathogens that are carried by the house fly.

Future perspectives

Mechanical transmission of pathogens by arthropods including house flies is often overlooked because too much importance is given to biologically transmitted diseases such as malaria, yellow fever etc. [26]. Nevertheless, there is enough evidence to show that house flies can carry pathogens capable of causing serious diseases in humans and domestic animals, and should therefore be controlled. The control of the house fly can be achieved by physical (such as composting manure [95, 96]), chemical and biological methods. The use of chemical pesticides, which is the most common method today, is fast losing grounds due to the growing resistance by the house fly and other pests, couple to the effects they may have on non-target organisms [97–99], have led to the consideration of other methods, including biological control. Biological control agents including fungi of the genera Metarhizium and Beauveria, and bacteria including Bacillus thuringiensis can be used to control the housefly [93, 97]. Furthermore, the sequencing of the genome of the house fly presents new opportunities for the identification of novel targets for controlling the housefly and also for understanding the mechanism of resistance to insecticides as well as the genetic adaptation of the house fly to high pathogen loads [69].

Conclusion

This review showed that the common house fly is a mechanical vector of a diverse range of pathogens including bacteria, fungi, viruses and parasites. However, more studies on identifying new pathogens and the survival of these pathogens are needed.

Additional file

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) Checklist. (PDF 490 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Health Policy Research Center (HPRC) of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. Acknowledgments also go to Dr. Natasha Potgieter and Dr. Farhat Afrin for the kind comments.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The original research articles included in this systematic review are publicly available.

Abbreviations

- EAEC

Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli

- EHEC

Enterohaemorhagic Escherichia coli

- EPEC

Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli

- ETEC

Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- PRRS

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome

Authors’ contributions

FK and KET conceived of the idea and participated in the design of this study. FK, KBL, BH and KET read and approved the final version of the paper.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hussein SA, John LC. Housefly, Musca domestica Linnaeus (Insecta: Diptera: Muscidae) Inst Food Agric Scie. 2014;47:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ommi D, Hashemian SM, Tajbakhsh E, Khamesipour F. Molecular detection and antimicrobial resistance of Aeromonas from houseflies (Musca domestica) in Iran. Revista MVZ Córdoba. 2015;20(Suppl):4929–4936. doi: 10.21897/rmvz.8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szalanski AL, Owens CB, McKay T, Steelman CD. Detection of Campylobacter and Escherichia coli O157:H7 from filth flies by polymerase chain reaction. Medical and Veterinary Entomology. 2004;18:241–246. doi: 10.1111/j.0269-283X.2004.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waheeda I, Muhammad FM, Muhammad KS, Iqra A, Iram N, Aqsad R. Role of housefly (Musca domestica, Diptera; Muscidae) as a disease vector. J. Entomol. & Zool. 2014;2(2):159–163. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization . Guidelines for the Control of Shigellosis, Including Epidemics of Child and Adolescent Health and Development. Geneva: WHO; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smallegange RC, den Otter CJ. Houseflies, annoying and dangerous. In Emerging pests and Vector-borne diseases in Europe Vol 1. Takken W and Knols BGJ. Wageningen Academic Publishers: The Netherlands. 2007. Pg. 281–292.

- 7.Awache I, Farouk AA. Bacteria and fungi associated with houseflies collected from cafeteria and food Centres in Sokoto. FUW Trends Scie Technol J. 2016;1(1):123–125. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsagaan A, Kanuka I, Okado K. Study of pathogenic bacteria detected in fly samples using universal primer-multiplex PCR. Mongolian J Agricultural Scie. 2015;15(2):27–32. doi: 10.5564/mjas.v15i2.541. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nassiri H, Zarrin M, Veys-Behbahani R, Faramarzi S, Nasiri A. Isolation and identification of pathogenic filamentous fungi and yeasts from adult house fly (Diptera: Muscidae) captured from the hospital environments in Alivaz city, Southwestern Iran. J Med Entomol. 2015;52(6):1351–1356. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjv140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bahrndorff S, de Jonge N, Skovgård H, Nielsen JL. Bacterial Communities Associated with Houseflies (Musca domestica L.) Sampled within and between Farms. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(1):e0169753. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levine OS, Levine MM. Houseflies (Musca domestica) as mechanical vectors of shigellosis. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13(4):688–696. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.4.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nichols GL. Fly Transmission of Campylobacter. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11(3):361–364. doi: 10.3201/eid1103.040460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farag TH, Faruque AS, Wu Y, Das SK, Hossain A, Ahmed S, Ahmed D, Nasrin D, Kotloff KL, Panchilangam S, Nataro JP, Cohen D, Blackwelder WC, Levine MM. Housefly Population Density Correlates with Shigellosis among Children in Mirzapur, Bangladesh: A Time Series Analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(6):e2280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.AHA K, Akram W. The effect of temperature on the toxicity of insecticides against Musca domestica L.: Implications for the effective management of diarrhea. PLos One. 2014;9(4):e95636. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davari B, Kalantar E, Zahirnia A, Moosa-Kazemi SH. Frequency of Resistance and Susceptible Bacteria Isolated from Houseflies. Iran J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2010;4(2):50–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang W. Houseflies as Potential Vectors for Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria. THESIS. Graduate Program in Food Science and Nutrition: The Ohio State University; 2013.

- 17.Zurek L, Ghosh A. Insects represent a link between food animal farms and the urban environment for antibiotic resistance traits. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80(12):3562–3567. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00600-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Solà-Ginés M, González-López JJ, Cameron-Veas K, Piedra-Carrasco N, Cerdà-Cuéllar M, Migura-Garcia L. Houseflies (Musca domestica) as Vectors for Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli on Spanish Broiler Farms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81(11):3604–3611. doi: 10.1128/AEM.04252-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hemmatinezhad B, Ommi D, Hafshejani TT, Khamesipour F. Molecular detection and antimicrobial resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from houseflies (Musca domestica) in Iran. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. 2015;21:18. doi: 10.1186/s40409-015-0021-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nazari M, Mehrabi T, Mostafa SH, Alikhani MY. Bacterial Contamination of Adult House Flies (Musca domestica) and Sensitivity of these Bacteria to Various Antibiotics, Captured from Hamadan City, Iran. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(4):DC04–DC07. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/23939.9720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doud CW, Zurek L. Enterococcus faecalis OG1RF:pMV158 Survives and Proliferates in the House Fly Digestive Tract. J Med Entomol. 2012;49(1):150–155. doi: 10.1603/ME11167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarwar M. Insect Vectors Involving in Mechanical Transmission of Human Pathogens for Serious Diseases. Int J Bioinformatics Biomed Engineering. 2015;1(3):300–306. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pava-Ripoll M, GRE P, Miller AK, Tall BD, Keys CE, Ziobro GC. Ingested Salmonella enterica, Cronobacter sakazakii, Escherichia coli O157:H7, and Listeria monocytogenes: transmission dynamics from adult house flies to their eggs and first filial (F1) generation adults. BMC Microbiol. 2015;15:150. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0478-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fisher ML, Fowler FE, Denning SS, Watson DW. Survival of the House Fly (Diptera: Muscidae) on Truvia and Other Sweeteners. J Med Entomol. 2017;54(4):999–1005. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjw241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, the PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foil LD, Gorham JR. Mechanical Transmission of Disease Agents by Arthropods. Chapter 12. In: Eldridg BF, Edman JD, editors. Medical Entomology, Revised Edition: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2004. p. 461–514. 10.1007/978-94-007-1009-2_12

- 27.De Jesús AJ, Olsen AR, Bryce JR, Whiting RC. Quantitative contamination and transfer of Escherichia coli from foods by houseflies, Musca domestica L. (Diptera: Muscidae) Int J Food Microbiol. 2004;93(2):259–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pava-Ripoll M, REG P, Miller AK, Ziobro GC. Prevalence and Relative Risk of Cronobacter spp., Salmonella spp., and Listeria monocytogenes Associated with the Body Surfaces and Guts of Individual Filth Flies. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78(22):7891–7902. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02195-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oo KN, Sebastian AA, Aye T. Carriage of enteric bacterial pathogens by house flies in Yangon, Myanmar. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1989;7(3–4):81–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alam MJ, Zurek L. Association of Escherichia coli O157:H7 with Houseflies on a Cattle Farm. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70(12):7578–7580. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.12.7578-7580.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Förster M, Messler S, Pfeffer K, Sievert K. Synanthropic flies as potential transmitters of pathogens to animals and humans. Mitteilungen der Deutschen Gesellschaft für allgemeine und angewandte Entomologie. 2009;17:327–329. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wasala L, Talley JL, Desilva U, Fletcher J, Wayadande A. Transfer of Escherichia coli O157:H7 to spinach by house flies, Musca domestica (Diptera: Muscidae) Phytopathology. 2013;103(4):373–380. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-09-12-0217-FI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fleming A, Kumar HV, Joyner C, Reynolds A. Nayduch1 D. Temporospatial fate of bacteria and immune effector expression in house flies (Musca domestica L.) fed GFP-E. coli O157:H7. Med Vet Entomol. 2014;28(4):364–371. doi: 10.1111/mve.12056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Songe MM, Hang’ombe BM, TJD K-J, Grace D. Antimicrobial Resistant Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli and Salmonella spp. in Houseflies Infesting Fish in Food Markets in Zambia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(1):21. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14010021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blaak H, Hamidjaja RA, van Hoek AHAM, de Heer L, de Roda Husman AM, Schets FM. Detection of Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase (ESBL)-Producing Escherichia coli on Flies at Poultry Farms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80(1):239–246. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02616-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soheyliniya S, Barin A. The role of house fly (Musca domestica) in transmission of pathogenic strains of E. coli. J Veterinary Res. 2014;69(1):9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greenberg B, Kowalski JA, Klowden MJ. Factors Affecting the Transmission of Salmonella by Flies: Natural Resistance to Colonization and Bacterial Interference. Infect Immun. 1970;2(6):800–809. doi: 10.1128/iai.2.6.800-809.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khalil K, Lindblom GB, Mazhar K, Kaijser B. Flies and water as reservoirs for bacterial enteropathogens in urban and rural areas in and around Lahore. Pakistan. Epidemiol Infect. 1994;113(3):435–444. doi: 10.1017/S0950268800068448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holt PS, Geden CJ, Moore RW, Gast RK. Isolation of Salmonella enterica Serovar Enteritidis from Houseflies (Musca domestica) found in Rooms Containing Salmonella Serovar Enteritidis-Challenged Hens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(19):6030–6035. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00803-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lamiaa B, Lebbadi M, Ahmed A. Bacteriological analysis of Periplaneta americana L. (Dictyoptera; Blattidae) and Musca domestica L. (Diptera; Muscidae) in ten districts of Tangier, Morocco. African J Biotechnol. 2007;6(17):2038–2042. doi: 10.5897/AJB2007.000-2315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cirillo VJ. “Winged sponges”: houseflies as carriers of typhoid fever in 19th- and early 20th-century military camps. Perspect Biol Med. 2006;49(1):52–63. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2006.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang YC, Chang YC, Chuang HL, Chiu CC, Yeh KS, Chang CC, Hsuan SL, Lin WH, Chen TH. Transmission of Salmonella between swine farms by the housefly (Musca domestica) J Food Prot. 2011;74(6):1012–1016. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-10-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shukla S, Chopra S, Ther SV, Sharma R, Sikrodia R. Isolation and identification of enterobacterial species from Musca domestica in broiler farms of Madhya Pradesh. Veterinary Practitioner. 2013;14(2):239–241. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kassiri H, Akbarzadeh K, Ghaderi A. Isolation of Pathogenic Bacteria on the House Fly, Musca domestica L. (Diptera: Muscidae), Body Surface in Ahwaz Hospitals, Southwestern Iran. Asian Pacific J Trop Biomed. 2012;2(2):S1116–S1119. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60370-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barreiro C, Albano H, Silva J, Teixeira P. Role of Flies as Vectors of Foodborne Pathogens in Rural Areas. ISRN Microbiology. 2013;Article ID 718780:7. doi: 10.1155/2013/718780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Butler JF, Garcia-Maruniak A, Meek F, Maruniak JE. Wild Florida house flies (Musca Domestica) as carriers of pathogenic bacteria. Florida Entomol. 2010;93(2):218–223. doi: 10.1653/024.093.0211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fotedar R, Banerjee U, Samantray JC, Shriniwas Vector potential of hospital houseflies with special reference to Klebsiella species. Epidemiol Infect. 1992;109(1):143–147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rahuma N, Ghenghesh KS, Ben Aissa R, Elamaari A. Carriage by the housefly (Musca domestica) of multiple-antibiotic-resistant bacteria that are potentially pathogenic to humans, in hospital and other urban environments in Misurata. Libya. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2005;99(8):795–802. doi: 10.1179/136485905X65134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Macovei L, Zurek L. Ecology of Antibiotic Resistance Genes: Characterization of Enterococci from Houseflies Collected in Food Settings. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72(6):4028–4035. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00034-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ahmad A, Ghosh A, Schal C, Zurek L. Insects in confined swine operations carry a large antibiotic resistant and potentially virulent enterococcal community. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hussein AN. Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of Candida species isolated from some domestic insects in Diwaniya city/Al–Qadisiya governorate. Wasit J Scie Med. 2014;7(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kumara HNS, Murali S, Thyagaraj NE, Ghosh SK. Survey and Isolation of natural incidence of different fungal pathogens against house flies in different urban habitats. JBiopest. 2013;6(2):133–138. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Banjo AD, Lawal OA, Adeduji OO. Bacteria and fungi isolated from housefly (Musca domestica L.) larvae. African J Biotechnol. 2005;4(8):780–784. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Förster M, Klimpel S, Sievert K. The house fly (Musca domestica) as a potential vector of metazoan parasites caught in a pig-pen in Germany. Veterinary Parasitol. 2009;160(1–2):163–167. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.10.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Phoku JZ, Bernard TG, Potgieter N, Dutton MF. Fungi in housefly (Musca domestica L.) as a disease risk indicator – A case study in South Africa. Acta Tropica. 2014;140:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2014.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ysquierdo CA, Olafson PU, Thomas DB. Fungi Isolated From House Flies (Diptera: Muscidae) on Penned Cattle in South Texas. J Med Entomol. 2017;54(3):705–711. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjw214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Senna Nunes MS, da Costa GL, Elias VR, Bittencourt P. Isolation of Fungi in Musca domestica Linnaeus, 1758 (Diptera: Muscidae) Captured at Two Natural Breeding Grounds in the Municipality of Seropédica, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro. 2002;97(8):1107–1110. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762002000800007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davari B, Khodavaisy S, Ala F. Isolation of fungi from housefly (Musca domestica L.) at Slaughter House and Hospital in Sanandaj, Iran. J Preventive Med Hygiene. 2012;53(3):172–4. [PubMed]

- 59.Kassiri H, Zarrin M, Veys-Behbahani R, Faramarzi S, Kasiri A. Isolation and Identification of Pathogenic Filamentous Fungi and Yeasts From Adult House Fly (Diptera: Muscidae) Captured From the Hospital Environments in Ahvaz City. Southwestern Iran. Journal of Medical Entomology. 2015;52(6):1351–1356. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjv140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Phoku JZ, Barnard TG, Potgieter N, Dutton MF. Fungal dissemination by housefly (Musca domestica L.) and contamination of food commodities in rural areas of South Africa. Int J Food Microbiol. 2016;217:177–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eke SS, Idris AR, Omalu ICJ, Otuu CA, Ibeh EO, Ubanwa ED, Luka J, Paul S. Relative abundance of synanthropic flies with associated parasites and pathogens in Minna Metropolis, Niger State. Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Parasitology. 2016;37(2):142–146. doi: 10.4314/njpar.v37i2.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nwangwu UC, Onyido AE, Egbuche CM, Iwueze MO, Ezugbo-Nwobi IK. Parasites Associated with wild-caught houseflies in Awka metropololis. IOSR J Pharma Biol Scie. 2013;6(1):12–19. doi: 10.9790/3008-0611219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ahmadu YM, Goselle ON, Ejimadu LC, James Rugu NN. Microhabitats and Pathogens of Houseflies (Musca domestica): Public Health Concern. Electronic J Biol. 2016;12(4):374–380. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oyeyemi OT, Agbaje MO, Okelue UB. Food-borne human parasitic pathogens associated with household cockroaches and houseflies in Nigeria. Parasite Epidemiol Cont. 2016;1(1):10–13. doi: 10.1016/j.parepi.2015.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Graczyk TK, Cranfield MR, Fayer R, Bixler H. House flies (Musca domestica) as transport hosts of Cryptosporidium parvum. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61(3):500–504. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tyasasmaya T, Wuryastuty H, Wasito W, Sievert K. Avian Influenza Virus H5N1 Remained Exist in Internal organs of House Flies 24 Hours Post-infection. J Veteriner. 2016;17(2):205–10.

- 67.Barin A, Arabkhazaeli F, Rahbari S, Madani SA. The housefly, Musca domestica, as a possible mechanical vector of Newcastle disease virus in the laboratory and field. Med Vet Entomol. 2010;24(1):88–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2009.00859.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haddow AD, Nasar F, Schellhase CW, Moon RD, Padilla SL, Zeng X, Wollen-Roberts SE, Shamblin JD, Grimes EC, Zelko JM, Linthicum KJ, Bavari S, Pitt ML, Trefry JC. Low potential for mechanical transmission of Ebola virus via house flies (Musca domestica) Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:218. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2149-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scott JG, Warren WC, Beukeboom LW, Bopp D, Clark AG, Giers SD, Hediger M, Jones AK, Kasai S, Leichter CA, Li M, Meisel RP, Minx P, Murphy TD, Nelson DR, Reid WR, Rinkevich FD, Robertson HM, Sackton TB, Sattelle DB, Thibaud-Nissen F, Tomlinson C, van de Zande L, Walden KKO, Wilson RK, Liu N. Genome of the house fly, Musca domestica L., a global vector of diseases with adaptations to a septic environment. Genome Biol. 2014;15:466. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0466-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Allen SJ, Thomas JE, Alexander NDE, Bailey R, Emerson PM. Flies and Helicobacter pylori infection. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:1037–1038. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.045880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grübel P, Hoffman JS, Chong FK, Burstein NA, Mepani C, Cave DR. Vector potential of houseflies (Musca domestica) for Helicobacter pylori. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35(6):1300–1303. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1300-1303.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vaira D, Holton J. Vector potential of houseflies (Musca domestica) for Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 1998;3(1):65–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bahrndorff S, Gill C, Lowenberger C, Skovgård H, Hald B. The effects of temperature and innate immunity on transmission of Campylobacter jejuni (Campylobacterales: Campylobacteraceae) between life stages of Musca domestica (Diptera: Muscidae) J Med Entomol. 2014;51(3):670–677. doi: 10.1603/ME13220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rosef O, Kapperud G. House flies (Musca domestica) as possible vectors of Campylobacter fetus subsp. jejuni. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;45(2):381–383. doi: 10.1128/aem.45.2.381-383.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Royden A, Wedley A, Merga JY, Rushton S, Hald B, Humphrey T, Williams NJ. A role for flies (Diptera) in the transmission of Campylobacter to broilers? Epidemiol Infect. 2016;144(15):3326–3334. doi: 10.1017/S0950268816001539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fasanella A, Scasciamacchia S, Garofolo G, Giangaspero A, Tarsitano E, Adone R. Evaluation of the House Fly Musca domestica as a Mechanical Vector for an Anthrax. PLoS One. 2010;5(8):e12219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nayduch D, Cho H, Joyner C. Staphylococcus aureus in the House Fly: Temporospatial Fate of Bacteria and Expression of the Antimicrobial Peptide defensing. J Med Entomol. 2013;50(1):171–178. doi: 10.1603/ME12189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hernández-Escareño JJ. Presence of Enterobacteriaceae, Listeria spp., Vibrio spp and Staphylococcus spp in House fly (Musca domestica L.), Collected and Macerated from Different Sites in Contact with a few Animals Species. Revista Científica. 2012;22(2):128–134. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gupta AK, Nayduch D, Verma P, Shah B, Ghate HV, Patole MS, Shouche YS. Phylogenetic characterization of bacteria in the gut of house flies (Musca domestica L.) FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2012;79(3):581–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nayduch D, Noblet GP, Stutzenberger FJ. Vector potential of houseflies for the bacterium Aeromonas caviae. Med Vet Entomol. 2002;16(2):193–198. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2002.00363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nayduch D, Honko A, Noblet GP, Stutzenberger F. Detection of Aeromonas caviae in the common housefly Musca domestica by culture and polymerase chain reaction. Epidemiol Infect. 2001;127(3):561–566. doi: 10.1017/S0950268801006240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ranjbar R, Izadi M, Hafshejani TT, Khamesipour F. Molecular detection and antimicrobial resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae from house flies (Musca domestica) in kitchens, farms, hospitals and slaughterhouses. J Infect Public Health. 2016;9(4):499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sulaiman S, Othman MZ, Aziz AH. Isolations of enteric pathogens from synanthropic flies trapped in downtown Kuala Lumpur. J Vector Ecol. 2000;25(1):90–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Joyner C, Mills MK, Nayduch D. Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Musca domestica L.: Temporospatial Examination of Bacteria Population Dynamics and House Fly Antimicrobial Responses. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e79224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cafarchia C, Lia RP, Romito D, Otranto D. Competence of the housefly, Musca domestica, as a vector of Microsporum canis under experimental conditions. Medical and Veterinary Entomology. 2009;23(1):21–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2008.00785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Otake S, Dee SA, Moon RD, Rossow KD, Trincado C, Farnham M, Pijoan C. Survival of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in houseflies. Can J Vet Res. 2003;67(3):198–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ommi D, Hemmatinezhad B, Hafshejani TT, Khamesipour F. Incidence and antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter and Salmonella from houseflies (Musca domestica) in kitchens, farms, hospitals and slaughter houses. Proc Natl Acad Sci India Sect B Biol Sci. 2017;87(4):1285–1291.

- 88.Lietzea VU, Geden CJ, Doyle MA, Bouciasa DG. Disease Dynamics and Persistence of Musca domestica Salivary Gland Hypertrophy Virus Infections in Laboratory House Fly (Musca domestica) Populations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78(2):311–317. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06500-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nazni WA, Seleena B, Lee HL, Jeffery J, Rogayah TA T, Sofian MA. Bacteria fauna from the house fly, Musca domestica (L.) Trop Biomed. 2005;22(2):225–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gill C, Bahrndorff S, Lowenberger C. Campylobacter jejuni in Musca domestica: An examination of survival and transmission potential in light of the innate immune responses of the house flies. Insect Sci. 2017;24(4):584–598. doi: 10.1111/1744-7917.12353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Barro N, Aly S, Tidiane OCA, Sababenedjo TA. Carriage of Bacteria by Proboscises, Legs, and Feces of Two Species of Flies in Street Food Vending Sites in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. J Food Protection. 2006;69(8):2007–2010. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-69.8.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Vazirianzadeh B, Solary SS, Rahdar M, Hajhossien R, Mehdinejad M. Identification of bacteria which possible transmitted by Musca domestica (Diptera: Muscidae) in the region of Ahvaz, SW Iran. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2008;1(1):28–31. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Farooq M, Freed S. Infectivity of housefly, Musca domestica (Diptera: Muscidae) to different entomopathogenic fungi. Braz J Microbiol. 2016;47(4):807–816. doi: 10.1016/j.bjm.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Service M. Medical Entomology for Students. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2008. pp. 140–141. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Abu-Rayyan AM, Abu-Irmaileh BE, Akkawi MM. Manure composting reduces house fly population. J Agricultural Safety Health. 2010;16(2):99–110. doi: 10.13031/2013.29594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lazarus WF, Rutz DA, Miller RW, Brown DA. Costs of existing and recommended manure management practices for house fly and stable fly (Diptera: Muscidae) control on dairy farms. J Econo Entomol. 1989;82(4):1145–1151. doi: 10.1093/jee/82.4.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kwenti ET . Biological Control of Parasites, Natural Remedies in the Fight against Parasites, Prof. Hanem Khater (Ed.), InTech: Croatia.(2017) Pg. 23–58. 10.5772/68012

- 98.Shono T, Zhang L, Scott JG. Indoxacarb resistance in the house fly, Musca domestica. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2004;80:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2004.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Abbas N, Khan HA, Shad SA. Cross-resistance, genetics, and realized heritability of resistance to fipronil in the house fly, Musca domestica (Diptera: Muscidae): a potential vector for disease transmission. Parasitol Res. 2014;113(4):1343–1352. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-3773-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) Checklist. (PDF 490 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The original research articles included in this systematic review are publicly available.