Abstract

Cubital tunnel syndrome is the second most common peripheral nerve compression seen by hand surgeons. A thorough understanding of the ulnar nerve anatomy and common sites of compression are required to determine the cause of the neuropathy and proper treatment. Recognizing the various clinical presentations of ulnar nerve compression can guide the surgeon to choose examination tests that aid in localizing the site of compression. Diagnostic studies such as radiographs and electromyography can aid in diagnosis. Conservative management with bracing is typically trialed first. Surgical decompression with or without ulnar nerve transposition is the mainstay of surgical treatment. This article provides a review of the ulnar nerve anatomy, clinical presentation, diagnostic studies, and treatment options for management of cubital tunnel syndrome.

Keywords: Cubital tunnel syndrome, Medial epicondylectomy, Thoracic outlet syndrome, Brachial plexus compression, Ulnar nerve decompression

1. Introduction

Ulnar nerve entrapment is the second most common compression neuropathy in the upper extremity after carpal tunnel syndrome.1,2 Compression of the ulnar nerve may occur at multiple points along its course; however, entrapment of the ulnar nerve at the elbow, known as cubital tunnel syndrome, is the most common site.3 Symptoms of ulnar neuropathy may manifest due to impingement of the nerve roots in the cervical spine, compression in the brachial plexus, thoracic outlet syndrome, or entrapment at the elbow, forearm, or wrist.3, 4, 5 Despite the myriad of literature available regarding cubital tunnel syndrome, the diagnosis remains a challenge as patients often do not recognize the presence of ulnar nerve entrapment until the symptoms are severe and the nerve has been damaged. Patients often present with both sensory and motor deficits, the latter indicating a late presentation consistent with a less favorable prognosis.6 The degree of sensory and motor deficits dictate treatment recommendations ranging from conservative treatment to surgery. A detailed understanding of the anatomy and pathophysiology of each individual patient's case of cubital tunnel syndrome is paramount for proper diagnosis and treatment.

2. Anatomy

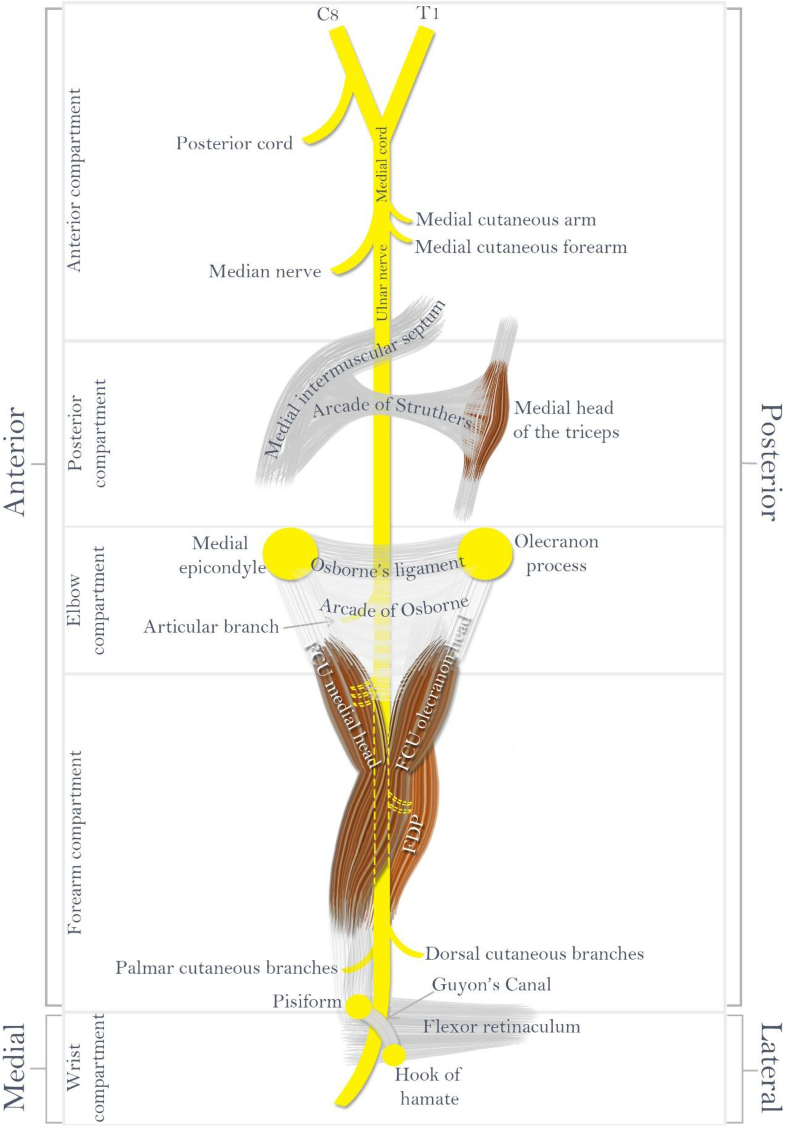

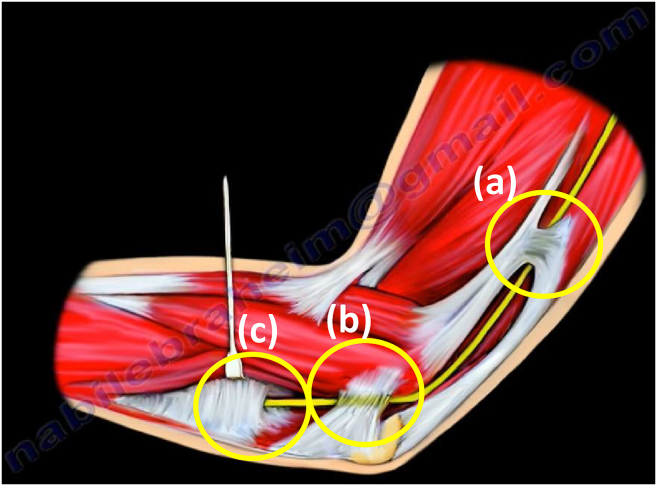

The ulnar nerve originates from the C8 and T1 nerve roots which coalesce to form the medial cord of the brachial plexus (Fig. 1).1,2,4,5 The medial cord gives off numerous branches as it works through the brachial plexus before bifurcating into two terminal branches, one contributing to the median nerve, and the other becoming the origin of the ulnar nerve. The ulnar nerve then courses down the arm in the anterior muscular compartment, eventually transitioning to the posterior muscular compartment by penetrating the medial intermuscular septum of the arm. The nerve is commonly compressed as it passes under the arcade of Struthers (Fig. 2a), an aponeurotic band that connects the medial intermuscular septum to the medial head of the triceps.4 At the elbow, the ulnar nerve traverses through structures that make up the cubital tunnel. The cubital tunnel's ceiling is formed by Osborne's ligament (also known as the cubital retinaculum) (Fig. 2b), a ligament spanning from the medial epicondyle to the olecranon process that is continuous with the fascia connecting the humeral and ulnar heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) (Fig. 2c).7 In some patients, the ceiling is replaced by the aconeus epitrochearlis muscle, thought to be an accessory cause of ulnar nerve compression in some patients.4 The tunnel floor is made up of the medial collateral ligament (MCL) and elbow joint capsule, while the medial epicondyle and olecranon act as the walls on either side.8 James et al.9 showed that the ulnar nerve is maximally compressed between Osborne's ligaments and the MCL in this tunnel at 135° of elbow flexion, decreasing the tunnel's height, area and sagittal curvature. After the ulnar nerve passes posterior to the medial epicondyle, it enters the forearm between the two heads of flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU), which is the most common site of ulnar nerve compression.10 It then travels alongside the ulna as it courses towards the wrist, staying deep to the FCU and superficial to the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP). In the distal part of the forearm, the ulnar nerve moves lateral to the FCU and medial to the ulnar artery as it traverses Guyon's canal to enter the palm. Pressure on the nerve at any of these sites can cause numbness or pain in the elbow, hand, or fingers.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the major structures the ulnar nerve traverses through the arm.

Fig. 2.

Major sites of compression are the (a) arcade of Struthers, (b) the Osborne ligament (cubital retinaculum), and (c) the arcade of Osborne between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris.

The ulnar nerve gives off many branches throughout its path down the arm. It first provides an articular branch at the elbow, followed by multiple motor branches to the FCU and medial half of the FDP.4 Prior to Guyon's canal, the nerve gives off dorsal and palmar cutaneous branches that supply the dorso-ulnar hand, and dorsal fourth and fifth digits, and ulnar palm, respectively.2 Once in the palm of the hand, the nerve's terminal motor branches innervate the intrinsic muscles: hypothenars, interosseous, third and fourth lumbricals, palmaris brevis, and adductor pollicis.8 Terminal sensory branching provides sensory innervation to the ulnar-sided palmar and dorsal aspects of the hand, as well as the small finger and ulnar half of the ring finger.4

3. Clinical presentation

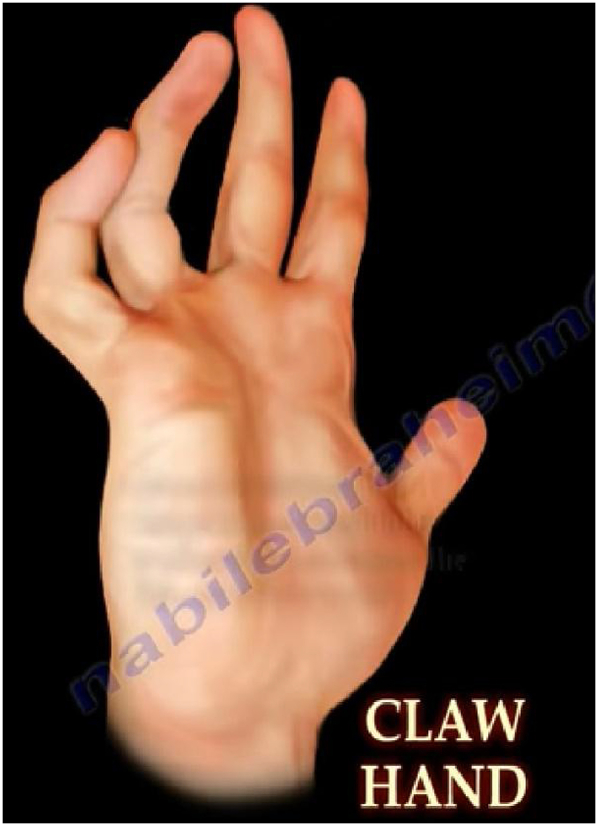

Compression of the ulnar nerve can involve both sensory and motor deficits, ranging from intermittent to constant decrease in function.5 It can start as paresthesia in the ulnar nerve sensory distribution, including the ulnar fourth and entire fifth finger, and may ultimately result in muscular weakening and muscular atrophy over time if left untreated.4,6 Patients may notice point tenderness and pain overlying the nerve at the medial aspect of the elbow due to inflammation. As elbow flexion compresses the area of the cubital tunnel and pinches the nerve,1,2,7,11,12 paresthesias are often exacerbated by elbow flexion activities such as phone use or athletic activities that require repetitive elbow motion. Night symptoms severe enough to cause awakening are a common complaint as many people sleep with the elbow in a flexed position.2 More severe symptoms of chronic cubital tunnel syndrome include a weak or clumsy hand, weakness affecting the ring or small finger, or muscle wasting. Patients may have difficulties with day to day activities like opening jars or holding a pencil. Eventually, the hand may begin to take on a claw deformity due to intrinsic muscle weakness and unopposed function of the FDP.4

During examination, the patient's affected extremity should first be inspected and palpated to detect any muscular atrophy, ring and small finger clawing, or ulnar nerve subluxation over the medial epicondyle as the elbow is taken through full range of motion.5 Sensation should also be examined in the ulnar nerve distribution, namely the ulnar side of the hand and fourth and fifth digits. The ulnar claw hand deformity (Fig. 3) is an advanced symptom of ulnar nerve entrapment below the elbow and typically causes flexion and clawing of the fourth and fifth fingers; this is due to a deficit in the third and fourth lumbricals, allowing the FDP to overpower the hand function.6 The ability to properly flex the metacarpophalangeal joints or extend the interphalangeal joints is hindered, resulting in the claw deformity.2

Fig. 3.

Claw hand deformity resulted from ulnar nerve damage.

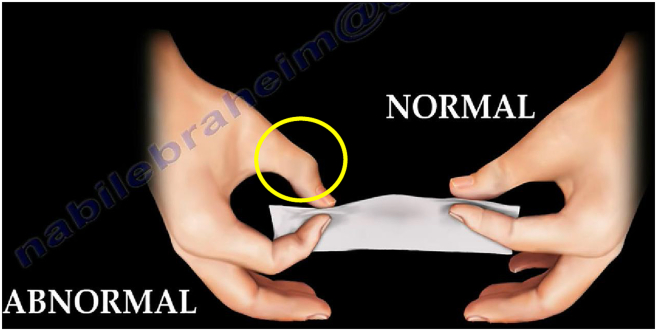

There are several clinical examinations commonly used to test the motor function and integrity of the ulnar nerve (Table 1). Weakness demonstrated during these tests compared to the contralateral side may indicate ulnar nerve compression. The first muscle innervated by the nerve is the FCU. To test function of this muscle, have the patient flex the wrist against resistance in an ulnar direction. Next, the ulnar nerve then gives branches to FDP. Test for weakness by having the patient flex the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint of the small finger against resistance. Moving down to the hand, the intrinsic muscles should be examined. Examine abduction of the small finger against resistance to test the abductor digiti minimi function.5 The same maneuver at the index finger will test the first dorsal interosseous (FDI) muscle function. Atrophy resulting in decreased compound muscle action potential (CMAP) of the FDI muscle could indicate bad prognosis for ulnar nerve recovery.13 When ulnar nerve impingement causes adductor pollicis muscle (APM) weakness, thumb adduction will not properly occur. To test this, have the patient attempt to pinch a piece of paper between the thumb and index finger; APM failure is demonstrated if thumb interphalangeal (IP) joint flexion rather than thumb adduction occurs.4 This is known as Froment's sign (Fig. 4) and is due to the compensatory action of the flexor pollicis longus muscle, innervated by the median nerve. Wartenberg's sign is caused by weakness of the third palmar interosseous and small finger lumbrical muscles and is a sign of late stage ulnar impairment.14 This is positive when the patient is asked to hold all fingers adducted and the small finger begins to abduct relative to the other digits.15

Table 1.

Tests for ulnar nerve motor function.

| Muscle | Test Instructions | Positive Sign |

|---|---|---|

| FCU | Flex wrist in ulnar direction against resistance | Weakness |

| FDP | Flex DIP of the small finger against resistance | Weakness |

| Abductor digiti minimi | Abduction of small finger against resistance | Weakness |

| 1st dorsal interosseous | Index finger abduction against resistance | Weakness |

| Adductor pollicis | Pinch a piece of paper between the thumb and index finger | Froment's sign: IP joint will flex |

| 3rd palmar interosseous/small finger lumbricals | Adduct all fingers | Wartenberg's sign: Small finger begins to abduct relative to other digits |

Fig. 4.

Froment's sign is positive when the adductor pollicis muscle fails, resulting in thumb interphalangeal (IP) joint flexion.

Provocative measures consist of Tinel's sign and elbow flexion test. Tinel's sign is performed by tapping on the nerve at the cubital tunnel to reproduce electric shock-like sensations, tingling, or numbness in the ulnar nerve sensory distribution.16,17 With the elbow flexion test, the patient is asked to fully flex the elbow with the shoulder in mild abduction. As the elbow flexes, the area of the cubital tunnel becomes narrow and compresses the nerve. Holding this position may result in tingling or paresthesia in the ulnar nerve distribution of the forearm or hand.10 In addition to elbow flexion, adding wrist flexion in an ulnar direction will aggravate the symptoms of cubital tunnel syndrome, and induce paresthesia due to contraction of the FCU muscle.1,6

4. Diagnostic studies

Differential diagnoses should include cervical nerve root impingement or injury, brachial plexopathy, thoracic outlet syndrome, Pancoast tumor, cubitus valgus, medial epicondyle osteophytes, or ulnar tunnel syndrome.4,10 Radiographs of the affected arm should be obtained to rule out bony deformity, soft tissue calcifications, or arthritic changes causing ulnar neuropathy.6,16 Cervical spine and chest radiographs are recommended to help rule out cervical radiculopathy and Pancoast tumor, respectively. To help localize the site of nerve compression, electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies can be useful. Electrodiagnostic studies aid in establishing the diagnosis, localizing the site of compression, and investigating the degree of ulnar nerve damage that has taken place.4,6,10 Differentiating the nerve pathology between axonal degeneration, segmental demyelination, and abnormal nerve irritability can provide links to its etiology and direct treatment protocol.2 Many metabolic factors can predispose an individual to ulnar nerve compression, thus, patients should be screened for systemic and metabolic conditions.1,5,10

5. Treatment

Conservative treatment measures focus on pain relief, inflammation reduction, and rehabilitation. This includes patient education and behavior modification, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs), night splints, elbow pads, physical therapy, ultrasound, pulsed signal therapy, and corticosteroid injections.2,5 Patients should be instructed to avoid aggravating activities, such as excessive motion of the joint or resting the nerve on hard surfaces. Night splints immobilize the elbow in 45° of extension with neutral forearm rotation, allowing inflammation to decrease. Both NSAIDs and corticosteroid injections remain controversial in their therapeutic benefit.2,10,18 Conservative management is successful about 50% of the time.19 If conservative management is not successful in preventing progression of impairment after several months, surgery may be required. Surgical management (Fig. 5) may consist of decompression of the nerve alone, decompression with ulnar nerve anterior transposition (subcutaneous, submuscular, or intramuscular), or medial epicondylectomy.8 Simple decompression can be performed endoscopically and avoid restrictive post-operative immobilization, though many criticize the high rates of recurrence in patients with greater than mild symptoms.18 Anterior transposition can be a more involved surgery, requiring significant disruption and manipulation of the nerve, but is indicated for more advanced cases of ulnar nerve pathology or as an adjunct procedure if decompression results in nerve instability.5 Medial epicondylectomy has been described for use when the ulnar nerve is visibly subluxing20; however. it has fallen out of favor due to destabilization of the elbow. Some advocates of a medial epicondylectomy do appreciate the limited amount of nerve dissection required and reduction in nerve strain.19

Fig. 5.

In situ ulnar nerve decompression.

6. Summary

Cubital tunnel syndrome is a common and debilitating condition that can be overlooked until after nerve damage has occurred.2 Timely recognition and treatment is paramount to good clinical outcomes to avoid irreversible muscle atrophy and functional deficit. Sites of compression are multifocal, requiring a thorough anatomic understanding of the course of the ulnar nerve throughout the arm. Other causes of ulnar neuropathy must be considered and localization of the site(s) of compression must be identified before surgical treatment is considered. Conservative measures can be successful for many patients, most applicable to those with mild symptoms. For those patients with symptoms refractory to conservative measures, surgical options including ulnar nerve decompression with or without anterior transposition or medial epicondylectomy remain the mainstay of management. Patients should consult with their doctor at the earliest signs of symptoms before determining a course of treatment.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2018.08.010.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Bozentka D.J. Cubital tunnel syndrome pathophysiology. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;(351):90–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robertson C., Saratsiotis J. A review of compressive ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2005;28(5):345. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karatas A., Apaydin N., Uz A., Tubbs R., Loukas M., Gezen F. Regional anatomic structures of the elbow that may potentially compress the ulnar nerve. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(4):627–631. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Folberg C.R., Weiss A.P., Akelman E. Cubital tunnel syndrome. Part I: presentation and diagnosis. Orthop Rev. 1994;23(2):136–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norkus S.A., Meyers M.C. Ulnar neuropathy of the elbow. Sports Med. 1994;17(3):189–199. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199417030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradshaw D.Y., Shefner J.M. Ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. Neurol Clin. 1999;17(3):447–461. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8619(05)70147-x. v-vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Granger A., Sardi J.P., Iwanaga J. Osborne's ligament: a review of its history, anatomy, and surgical importance. Cureus. 2017;9(3) doi: 10.7759/cureus.1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang J.H., Samadani U., Zager E.L. Ulnar nerve entrapment neuropathy at the elbow: simple decompression. Neurosurgery. 2004;55(5):1150–1153. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000140841.28007.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James J., Sutton L.G., Werner F.W., Basu N., Allison M.A., Palmer A.K. Morphology of the cubital tunnel: an anatomical and biomechanical study with implications for treatment of ulnar nerve compression. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(12):1988–1995. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Posner M.A. Compressive neuropathies of the ulnar nerve at the elbow and wrist. Instr Course Lect. 2000;49:305–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gelberman R.H., Yamaguchi K., Hollstien S.B. Changes in interstitial pressure and cross-sectional area of the cubital tunnel and of the ulnar nerve with flexion of the elbow. An experimental study in human cadavera. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(4):492–501. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199804000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Werner C.O., Ohlin P., Elmqvist D. Pressures recorded in ulnar neuropathy. Acta Orthop Scand. 1985;56(5):404–406. doi: 10.3109/17453678508994358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beekman R., Zijlstra W., Visser L.H. A novel points system to predict the prognosis of ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. Muscle Nerve. 2017;55(5):698–705. doi: 10.1002/mus.25406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldman S.B., Brininger T.L., Schrader J.W., Curtis R., Koceja D.M. Analysis of clinical motor testing for adult patients with diagnosed ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(11):1846–1852. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenthal E.A. Examination of hand and forearm: claw hand deformity & thumb deformity with ulnar palsy. In: Peimer C.A., editor. Surgery of the Hand and Upper Extremity. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1996. pp. 83–87. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ciccotti M.C., Schwartz M.A., Ciccotti M.G. Diagnosis and treatment of medial epicondylitis of the elbow. Clin Sports Med. 2004;23(4):693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2004.04.011. xi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montagna P., Liguori R. The motor tinel sign: a useful sign in entrapment neuropathy? Muscle Nerve. 2000;23(6):976–978. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(200006)23:6<976::aid-mus22>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Folberg C.R., Weiss A.P., Akelman E. Cubital tunnel syndrome. Part II: Treatment. Orthop Rev. 1994;23(3):233–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boone S., Gelberman R.H., Calfee R.P. The management of cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40(9):1897–1904. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.03.011. quiz 1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King T., Morgan F.P. Late results of removing the medial humeral epicondyle for traumatic ulnar neuritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1959;41-B(1):51–55. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.41B1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.