Abstract

Climate is an effective factor in the ecological structure which plays an important role in control and outbreak of the diseases caused by biological factors like malaria. With regard to the occurring climatic change, this study aimed to review the effects of climate change on malaria in Iran. In this systematic review, Cochrane, PubMed and ScienceDirect (as international databases), SID and Magiran as Persian databases were investigated through MESH keywords including climate change, global warming, malaria, Anopheles, and Iran. The related articles were screened and finally their results were extracted using data extraction sheets. Totally 41 papers were resulted through databases searching process. Finally 14 papers which met inclusion criteria were included in data extraction stage. The findings indicated that Anopheles mosquitoes are present at least in 115 places in Iran; they are compatible with climatic zones of Iran. Malaria and it’s vectors are affected by climate change. Temperature, precipitation, relative humidity, wind intensity and direction are the most important climatic factors affecting the growth and proliferation of Anopheles, Plasmodium and the prevalence of malaria. The transmission of malaria in Iran is associated with the climatic factors of temperature, rainfall, and humidity. Therefore, with regard to the occurring climatic change, the incidence of the disease may also change which needs to be taken into consideration while planning of malaria control.

Keywords: Climate change, Global warming, Malaria, Anopheles, Iran

Introduction

Climatic change refers to the long-term statistical changes in weather such as a change in the average weather conditions and/or the distribution of weather conditions around the average of long term weather (for example, the extreme weather events) (Wu et al. 2016; Parry et al. 2007). Climate change is an interconnected chain which starts from consuming fossil fuels in industrial activities and has various consequences. Nowadays, climate change has manipulated the world (Piao et al. 2010). Most of the scientific communities agree that the increase in the concentration of greenhouse gases by human activities leads to global warming and other climatic changes (Piao et al. 2010; Moradi et al. 2008). According to the results of different models across the world, the Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change (IPCC) has predicted that the world’s temperature would increase by 1.4–5.8 until 2100 (Piao et al. 2010). The increase in the temperature mostly takes place in the areas with higher latitude (Piao et al. 2010; Trenberth 2001). Moreover, due to durability and sustainability of greenhouse gasses and the impact of the climate system, the climatic changes will continue for at least several decades even if basic international preventive measures be adopted (Piao et al. 2010; Houghton and Firor 1995).

Climate change is expected to have a variety of effects on human health. One of them which has not been taken into consideration and has not been understood well, and is less predictable is infectious diseases transmitted through vectors. The concept that weather and climate are related to infectious diseases is known from Hippocrates time (Mills et al. 2010). The infectious agents such as protozoa, bacteria, viruses, and the related vector organisms (like mosquitoes, mites, and sand flies) lack the regulating mechanism of temperature. Hence, their reproductive and survival mechanisms are influenced by temperature fluctuations (Kovats et al. 2001; Hales et al. 2002); their dependence on temperature is observed in the relationship between the disease severity and weather changes during weeks, months, and years (Kuhn et al. 2003). There is a close geographical relationship between the climate key variables and the distribution of the transmitted diseases by the vectors (Patz et al. 2005).

Some pathogens are transmitted by the vectors or need mediator hosts to complete the life cycle. The appropriate climate and weather conditions are necessary for the vectors’ and hosts’ survival, reproduction, distribution, and transmission of disease pathogens. Therefore, the change in climate and weather conditions affects the pathogens, vectors, hosts, and their living environment and, hence, the infectious diseases (Epstein 2001; Wu et al. 2014).

Studies have indicated that the long-term climate warming provides the conditions for the geographical spread of the several infectious diseases (Epstein et al. 1998; Ostfeld and Brunner 2015; Rodó et al. 2013). Severe weather events may help to create opportunities for the spread of cluster diseases or the outbreak of the disease in non-traditional places and times (Epstein 2000). Overall, climatic conditions and weather affect time and the disease outbreak severity (Wu et al. 2014; Organization 2005). The warm and unstable climate is retrieving a dynamic role in the global emergence, revitalization, and redistribution of infectious diseases (Wu et al. 2016).

Furthermore, the indirect impacts of climatic change may increase the occurrence of natural hazards such as flood and extreme weather conditions; they are considered as factors that increasing the infectious diseases (Babaie et al. 2014). Malaria is one of the diseases which is claimed to be under the direct and indirect impact of climate change (Babaie et al. 2015a, b). Climate is an important factor in the ecological structure which plays an effective role in the control and spread of the diseases caused by biological factors (Rahimi and Morianzadeh 2016); particularly, the factors which spend a part of their life cycle out of the human body like the pathogens which are of carrier insects and are exposed to the environment weather (Kovats et al. 2003). Climatic and environmental conditions play an important role in the life cycle, duration of activity, and proliferation of Anopheles (Rahimi and Morianzadeh 2016) such that malaria is known as a climate-dependent disease (Mohammadkhani et al. 2016). Understanding of the relationship between climate and Malaria is very essential. These complicated multi-dimensional impacts include the potential impacts on the change in time and place of the transmitted diseases (Change 2007). According to the last statistics announced by the World Health Organization, 212 million cases with malaria were estimated in 2015, 429,000 of whom died (WHO 2015). In the epidemic regions in which the transmission of malaria epidemically takes place in short seasons or sporadically, it may lead to extreme death in all age groups (Caminade et al. 2014).

Malaria is still considered as an important health problem in Iran. Spatial distribution of the disease and its’ vectors is provided by using of geospatial information system (Salahimoghadam et al. 2014; Barati et al. 2012). Distribution map of malaria in Iran indicate that most of cases is focused in southeast areas (Barati et al. 2012). Our country is currently in the elimination phase of disease (Soleimani Ahmadi et al. 2012). As world malaria report, Iran (Islamic Republic of) is targeting elimination by 2020. Trends in Iran have declined from 1847 to 81 cases between 2010 and 2017(WHO 2017). Various regional and global evaluations of the effective models of malaria and climatic change have been released with different results (Caminade et al. 2014). A 30-year (1975–2005) study that have evaluated the climatic conditions for malaria outbreak in Iran indicated that the climatic factors are regarded as a risk factor for increasing the outbreak of malaria (Holakouie Naieni et al. 2012). Even in the endemic areas, malaria transmission is unstable and season-dependent. Most malaria infections take place in summer (Haghdoost 2004) and increase in August and September. Winter is too cold such that malaria cannot be transmitted and temperature and humidity are not usually so desirable until April. These seasonal models change annually and may provide the conditions for the incidence and transmission of malaria (Abeku et al. 2003; Teklehaimanot et al. 2004).

Although factors like urbanization, globalization, population movement, deforestation, interruption to control measures; and biotic factors like human host factors are affecting disease incidence and severity of malaria (Kumar and Reddy 2014), Climate change represents a potential environmental factor affecting disease outbreak (Anderson et al. 2004). With regard to the fact that malaria is a climate-dependent disease, the objective of this study was to review the climatic impact on malaria in Iran so as to come to a better understanding of the impacts that climatic changes have on malaria in Iran.

Methods

In this systematic review the effect of climate change on the malaria status in Iran has been investigated. Data were collected through searching in reputable Persian (SID and Magiran) and international databases (Cochrane, Pub med, and Science direct) and electronic resources using the keywords of climate change, global warming, malaria, Anopheles mosquito and Iran in the title, abstract and keywords (Table 1). The selected period for searching the articles was from 2007 to 2017. After searching of databases, the references of selected papers were used for a better identification and coverage.

Table 1.

Climate change effects on malaria prevalenc in Iran: results of evidences review

| Authors and year of publication | Place of study and study time | Title | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shemshad et al. (2007) | Iran, 2007 | Morphological and molecular characteristics of malaria vector Anopheles Superpictus populations in Iran | There are two completely different forms among different populations of Anopheles Superpictus in many places of the country simultaneously |

| Salahi-Moghaddam et al. (2017) | Iran, 1970–2015 | Spatial changes in the distribution of malaria vectors during the past 5 decades in Iran | Malaria transmission is reduced by rainfall. Heavy rainfalls destroy malaria larvae. The vector of malaria distribution is towards southern and eastern regions of the country which are influenced by the Indian monsoon rain |

| Halimi et al. (2013) | Iran, 1971–2005 | Climatic survey of malaria incidence in Iran during 1971–2005 | Precipitation has been the most important climatic factor controlling the annual changes of malaria such that the outbreak of the disease has a high correlation with precipitation (0.41). After precipitation, the humidity index had the maximum correlation (0.37) with the outbreak of malaria. The durability of the humidity resulted from extreme rainfall will provide the desirable conditions for the life and proliferation of Anopheles and the evolution of its larvae. The annual temperature mean had a lower correlation with the outbreak of malaria |

| Halimi et al. (2016) | Iran, 1974–2013 | Impact of El Nino southern oscillation (ENSO) on annual malaria occurrence in Iran | The provinces of Sistan and Balouchestan, Hormozgan, and tropical parts of Kerman which have a 3-million population, are called the “resistant malaria” region of Iran. The ENSO phenomenon can result in spatiotemporal expansion of the incidence of malaria and making large epidemics of Malaria by providing biological conditions for Anopheles, expanding the geography of the vector mosquito habitats, prolonging the favorable period for the activity and proliferation of Anopheles mosquitoes and displacement of the periods of activity of these mosquitoes, and expediting plasmodium sporogonic stages, etc |

| Halimi et al. (2013) | Iran, 1985–2005 | Survey of climatic condition of Malaria outbreak in Iran using GIS | Social, economic, and cultural factors, the quantity and quality of the programs for the control of malaria, border position and neighborhood with Pakistan and Afghanistan, and the issues related to immigrants also play an important role in the annual incidence of this disease and often influence the role of climatological factors in this province |

| Halimi et al. (2014) | Iran, 1975–2005 | Survey of climatic condition of Malaria outbreak in Iran using GIS | The provinces of Hormozgan, Boushehr, Khuzestan, Mazandaran, the southern area of Sistan and Balouchestan including Nik Shahr and Chabahar, and the western area of Gilan have the most desirable climatic conditions (temperature, humidity, and precipitation at the same time) for the reproduction and activity of Anopheles. The provinces of Golestan, North Khorasan, Tehran, Markazi, the northern area of Isfahan, Qom, Lorestan, Fars, and the southern area of Kerman, the northern area of Sistan and Balouchestan, and Qazvin have the second place in terms of desirable climatic conditions for the reproduction and activity of Anopheles. The provinces of Razavi Khorasan, South Khorasan, northern areas of Sistan and Balouchestan and Kerman, Yazd, Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad, Kermanshah, and Ilam have the third place. The minimum potential for the reproduction and activity of Anopheles is in the provinces of West Azerbaijan, East Azerbaijan, Kurdistan, the central area of Yazd, Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari, Zanjan, Hamadan, and Ardabil |

| Mozaffari et al. (2011) | Iran, Chabahar 1990–2007 | The effect of southern oscillation on malaria disease in Iran with emphasis on the town of Chabahar | South Oscillation with negative phase (E1 Nino) is along with an increase in the atmospheric deposition across the country and decreases the incidence of malaria; in the years in which the warm phase (La Nina) happens, the incidence of malaria increases. In Chabahar, the negative phase of South Oscillation is along with the reduction of rainfall and its positive phase is along with an increase in the rainfall |

| Mohammadkhani et al. (2016) | Iran, Kerman, 2000–2012 | The relation between climatic factors and malaria incidence in Kerman, South East of Iran | Temperature is the most effective meteorological factor in the incidence of malaria. The incidence rate of malaria has been considerably increased with the increased mean, maximum, and minimum monthly temperature |

| Raeisi et al. (2009) | Iran 2002–2007 | The trend of malaria in I.R. Iran from 2002 to 2007 | The malaria process during 2002–2007, except for 2003 in which it was unexpectedly increased compared to 2002, showed a steady descending trend. The main causes of increase in malaria cases in 2003 include unpredictable rainfall in August and September, creating large larvae genes in the eastern regions of Hormozgan and south of Sistan and Balouchestan, reduced temperature, and the abundance of vectors |

| Mozafari and Mostofialmammaleki (2012) | Iran, Chabahar, 2003–2008 | Bioclimatic analysis of the malaria outbreak in Chabahar | There is a positive, strong, and significant relationship between the incidence of the disease and the average temperature, average minimum temperature, and average maximum temperature. Furthermore, there is a negative, strong, and significant relationship between the incidence of the disease and annual rainfall |

| Rahimi and Morianzadeh (2016) | Iran, Kerman, 2016 | Analysis of the impact climate and ENSO on the malaria in kerman Provice | The high-risk regions of Iran in terms of the outbreak of malaria include south and southeast of Kerman province, Hormozgan, and the central and southern parts of Sistan and Balouchestan; the disease had a descending order after 2005. Temperature has a direct effect on the outbreak of malaria, but the number of the affected people decreases at temperatures more than 40 °C due to the impact on the biological stages of the vector. Temperature adjustment and increased relative humidity in October and November increase the number of the affected people and decrease it when the temperature takes a descending order in December |

| Jadgal et al. (2014) | Iran, Konarak, 2007–2011 | The epidemiological features of malaria in Konarak, Iran (2007–2011) | The main reasons for the vector increase in 2011were the decreased temperature and the abundance of the vectors. The maximum positive cases of malaria are related to 2007 whose reasons were unprecedented rainfall, floods and Gonvo hurricane, and the creation of ponds and larval habitats |

| Barati et al. (2014) | Iran, 2008–2010 | Assessment of malaria status in Iran | 99.5% of the disease transmission takes place in the southeastern region, in the provinces of Sistan and Balouchestan, Kerman, and Hormozgan. Malaria transmission had a descending order in the three years ending to 2011 which was probably due to climatic conditions such as global warming, decreased precipitation, and drought |

| Barati et al. (2012) | Iran, 2008–2010 | Spatial outline of malaria transmission in Iran | There was a significant relationship between malaria transmission and the minimum and maximum temperature in all of the studied regions. Yet, there was not a significant relationship between relative humidity and malaria transmission. Furthermore, there was a statistically significant relationship between malaria transmission and height such that 91% of the incidences took place in the regions with a height lower than 650 m and about 9% of the incidences took place in higher regions |

The inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria in this study were: Iran as the place of the study, time of the study (2007–2017), the subjects of the studies which had investigated the climatic changes in Iran, being in Persian and English, and availability of full text; the exclusion criteria included the articles which were not in Persian and English, summary of the articles presented on conferences, and educational articles.

Article screening process

Using the aforementioned keywords, all articles were examined by two researchers based on the primary search stages in Persian and English electronic resources and the references to the articles. Then, the related articles were identified and if the two researchers had different opinions, the opinion of the third researcher was also used.

Data collection

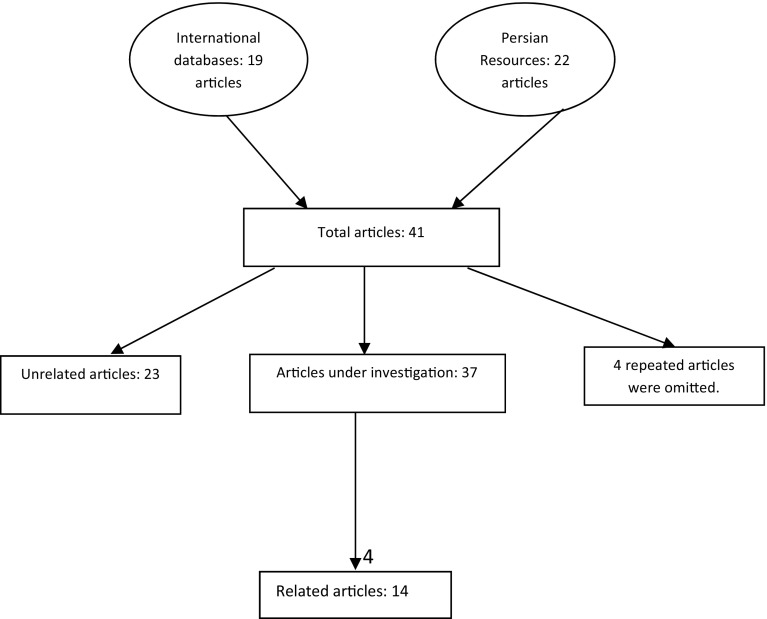

The information of 22 Persian articles and 19 English articles were investigated, of which 2 English articles and 2 Persian articles were repeated in Endnote software; hence, they were omitted and 37 articles were finally extracted (Fig. 1). The 37 articles were studied, 23 of which were known as unrelated and excluded from the study. Finally, 14 articles were selected for final review. The data extraction forms were provided based on the data available in the studies and the study objectives. The information form included title of the study, time of the study, year of publication, language of the study, place of the study (city), kind of the study, objectives of the study, materials and method, the information related to climate change, and summary of the results which were recorded in the forms following the data. At last, the final documents have entered the table and combined with the data available in other parts of the study.

Fig. 1.

The process of investigation and selection of the articles

Results

Searching of databases lead to 41 articles that finally 14 of them were selected for data extraction through screening process (Table 1). The published articles had investigated the information related to climate change and malaria from 1972 to 2015. The results indicated that Anopheles mosquitoes are present at least in 115 places in Iran; they are compatible with climatic zones of Iran. Anopheles mosquitoes may be seen in low lands with cold areas in central and northern parts and occupy humid and warm climates in the southern parts of the Iran (Salahi-Moghaddam et al. 2017). There are seven malaria vectors in Iran: Anopheles stephensi (An. stephensi), Anopheles culicifacies s.l. (An. culicifacies s.l.), Anopheles fluviatilis s.l. (An. fluviatilis s.l.), Anopheles dthali (An. dthali), Anopheles superpictus s.l., Anopheles maculipennis complex and Anopheles sacharovi. The first five species are responsible for active foci of malaria transmission of southern parts of Iran (Yeryan et al. 2016). Anopheles superpictus is one of the malaria vectors in the entire plateau of Iran and mountainous areas of Alborz and southern Zagros; it is less abundant in the coastal plains by the Caspian Sea and the Persian Gulf. Ardabil, an area with a cold and mountainous weather, has experienced the reappearance of malaria (Shemshad et al. 2007). The provinces of Hormozgan, Boushehr, Khuzestan, Mazandaran, the southern area of Sistan and Balouchestan including Nik Shahr and Chabahar, and the western area of Gilan have the most desirable climatic conditions (temperature, humidity, and precipitation at the same time) for the reproduction and activity of Anopheles. The provinces of Golestan, North Khorasan, Tehran, Markazi, the northern area of Isfahan, Qom, Lorestan, Fars, and the southern area of Kerman, the northern area of Sistan and Balouchestan, and Qazvin have the second place in terms of desirable climatic conditions for the reproduction and activity of Anopheles. The provinces of Razavi Khorasan, South Khorasan, northern areas of Sistan and Balouchestan and Kerman, Yazd, Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad, Kermanshah, and Ilam have the third place. The minimum potential for the reproduction and activity of Anopheles is in the provinces of West Azerbaijan, East Azerbaijan, Kurdistan, the central area of Yazd, Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari, Zanjan, Hamadan, and Ardabil (Halimi et al. 2013).

Many areas of Iran have the necessary climatic conditions for the transmission of malaria. Though malaria has been eliminated in northern and central areas, it is still observed in south tropical regions (Mozaffari et al. 2011). The distribution of malaria is toward southern and eastern regions which are influenced by the Indian monsoon rain (Beck-Johnson et al. 2017; Salahi-Moghaddam et al. 2017).

Temperature, precipitation, humidity, and land use are the important stimuli for the activity of Anopheles and the risk of malaria. Although the relationship between mosquito larval habitat and the amount of rainfall cannot be predicted because of its complexity, there is a positive relationship between them (Beck-Johnson et al. 2017). Temperature, rainfall, relative humidity, and wind intensity and direction are the most effective climatic factors in the outbreak of Malaria. Furthermore, temperature and humidity are two climatic factors affecting the growth and proliferation of Anopheles as well as the activity of Plasmodium parasite (Smith et al. 1999). Temperature is the most effective meteorological factor in the incidence of malaria. The incidence rate of malaria has been considerably increased with the increased mean, maximum, and minimum monthly temperature (Mohammadkhani et al. 2016). The outbreak of malaria has a high correlation with precipitation; the humidity index has the highest amount of correlation with the outbreak of malaria after precipitation. The durability of the humidity resulted from extreme rainfall will provide the desirable conditions for the life and proliferation of Anopheles and the evolution of its larvae. On the contrary, storm rainfall washes Anopheles’ eggs, limits the reproduction, and negatively affects the outbreak of the disease (Halimi et al. 2016). There is a positive, strong, and significant relationship between the incidence of the disease and the average temperature, average minimum temperature, and average maximum temperature; however, there is a negative, strong, and significant relationship between the incidence of the disease and the annual precipitation (Mozafari and Mostofialmammaleki 2012). Malaria in Iran is influenced by global warming and periodic droughts. There was a significant relationship between malaria transmission and the minimum and maximum temperature in all of the studied regions. Yet, there was not a significant relationship between relative humidity and malaria transmission. Furthermore, there was a statistically significant relationship between malaria transmission and height such that 91% of the incidences took place in the regions with a height lower than 650 m and about 9% of the incidences took place in higher regions (Barati et al. 2012).

The correlation of malaria annual incidence is negative with all months; it means that the years governed with ENSO warm phase, i.e. E1 Nino, had a higher incidence of malaria and the years which were of positive and high values of South Oscillation (years with cold phase or La Nina), the incidence of malaria was lower in which. The ENSO phenomenon can result in spatiotemporal expansion of the incidence of malaria and making large epidemics of malaria by providing biological conditions for Anopheles, expanding the geography of the vector mosquito habitats, prolonging the favorable period for the activity and proliferation of Anopheles mosquitoes and displacement of the periods of activity of these mosquitoes, and expediting Plasmodium sporogonic stages, etc. (Halimi et al. 2016). South Oscillation with negative phase (E1 Nino) is along with an increase in the atmospheric deposition across the country and decreases the incidence of malaria; in the years in which the warm phase (La Nina) happens, the incidence of malaria increases. In Chabahar, the negative phase of South Oscillation is along with the reduction of rainfall and its positive phase is along with an increase in the rainfall (Raeisi et al. 2009). The ENSO phenomenon has been approved to affect rainfall changes, rainfall intensity, flood event, increased temperature, the occurrence of thermal waves, and the outbreak of tropical disease (Rahimi and Morianzadeh 2016). The transmission of malaria has decreased during the 3 years ending to 2011 which is probably due to climatic conditions such as global warming, precipitation reduction, and drought (Barati et al. 2015; Salahimoghadam et al. 2014).

Discussion

When malaria was known in Iran, the disease was observed in the Caspian Sea coasts, Kurdistan, Azerbaijan, Kermanshah, Hamadan, Lorestan, Khuzestan, Fars, and Persian Gulf coasts; it was more severe in Boushehr and was less seen in Isfahan, Yazd, and Kerman. However, there was no sign of malaria in Sistan and Balouchestan (Floor 2004). A large part of Iran has the necessary climatic conditions for malaria transmission due to the desirable climatic conditions for the life and proliferation of Anopheles and the evolution of its larvae. Malaria is eliminated from northern and central regions, but it is still seen in the southern and eastern tropical regions. Temperature, precipitation, and humidity are the important stimuli for the activity of Anopheles and the risk of malaria. Malaria transmission is related to environmental, physical, and biological factors. The environmental factors include temperature, precipitation, and humidity. Biologic agents are the abundance of anopheles species, their desire to bite mankind, their sensitivity to the parasite, life span of mosquitoes, and the growth of parasites in mosquitoes that depend on independent environmental factors. Physical variables, such as soil moisture or its proxies (e.g. stream flow), improve transmission modeling, as they explain the interaction between precipitation, temperature, and the ground condition.

The vector insects are of cold-blooded animals; these insects and the pathogens they transmit are sensitive to climatic factors such that weather affects survival rate and reproduction of the vectors. This, on the one hand, affects the suitability of the habitat, distribution, frequency, the vectors’ activity and, on the other hand, affects the rate of growth, survival, and the reproduction of pathogens in the vectors (Bayoh and Lindsay 2003; Lardeux et al. 2008). Some scientists believe that global warming changes the world into an appropriate habitat for parasites. The Anopheles-borne falciparum malaria mostly exists when temperature is above 16 °C (Beck-Johnson et al. 2013). A temperature dropping to below this threshold will benefit malaria control (Wu et al. 2016). The outbreak of malaria is usually lower in the heights since the mountainous regions are very cold; therefore, these regions were not appropriate for the growth of mosquitoes and this disease was not observed in these areas. However, unfortunately, the climate warming has caused the warmer air to transfer to high regions and, as a result, the mountains change into a favorable environment for the growth of mosquitoes. This has recently resulted in the presence of malaria among the mountainous birds (Wang and Overland 2004).

Furthermore, the warmer weather facilitates the life cycle of these mosquitoes and makes them eat more. Hence, when it is warmer, a lot of people are significantly affected by them (Bouma and Van der Kaay 1994). The results of a study indicated that if temperature increases by 1 °C, the malaria infection increases by 337% over the 3 previous years. Therefore, climate change generally creates conditions which can result in the outbreak of the infectious diseases. Moreover, it is estimated that if the earth surface temperature increases by 1 °C, the number of deaths due to malaria is increased to 64,475 and the economic burden of illness in the world reaches 2.375 million dollars; most of the victims will be from China, Central Asia, east of Africa, and the southern regions of South America (Lindblade et al. 1999).

Some models predict that the continuation of global warming up to the end of the 21st century will extend the malaria potential transmission region from an area including 45% of the world population to the areas in which parasite is the cause of the disease which is resistant to standard drugs. In these models, malaria reemerges in the north and south of tropical regions (Wang and Overland 2004).

Widespread studies have been conducted on climatic changes. Martens et al. studied the population at risk of malaria and climatic changes and referred to the spatial displacement of malaria from tropical regions to cold regions (Martens et al. 1995). Lyndsay investigated the relationship between reduced malaria transmission and the rainfalls due to E1 Nino in Tanzania and stressed that precipitation has reduced the disease in the region (Lindsay et al. 2000). Mabaso et al. studied the relationship between E1 Nino and malaria annual incidence in the south of Africa (Mabaso et al. 2004). Wangdi et al. conducted a study in the endemic regions of Bhutan and showed that the average maximum temperature with a one-month delay had a positive strong prediction of the incidence of malaria (Wangdi et al. 2010). Pang et al. reported a positive relationship between the minimum monthly temperature and the outbreak of malaria in Xuan, China (Bi et al. 2003). Zhang et al. conducted a study in a temperate region in China and indicated that the minimum and maximum temperature have the most positive relationship with the monthly incidence of malaria such that if temperature increases by 1 °C, the incidence of malaria increases by 12–16%. The increased temperature, especially in some regions, increases the survival of Plasmodium and Anopheles in the winter and expedites the transmission and distribution of malaria in the population (Zhang et al. 2010). Hung et al. conducted a study in Moto, Tibet, and showed that the Spearman’s correlation of the incidence of malaria has a significantly positive relationship with temperature, humidity, and malaria. The maximum relationship was between the incidence of malaria and the mean, maximum, and minimum temperature with a one-month delay and the maximum relationship was between the incidence of malaria and precipitation with a two-month delay (Huang et al. 2011). Another study was done by Kim et al. using monthly parameters in Korea. They have indicated that there is a positive relationship between the outbreak of malaria and the mean, minimum, and maximum temperature such that a 1 °C-increase of the temperature resulted in a 16.1%-increase after one week and a 17.7%-increase after three weeks. Moreover, with a 10%-increase of humidity, the incidence of malaria increased by 10.4% on the same week (Kim et al. 2012). Zhao et al. conducted a study in Anhui province of China and showed that precipitation has the maximum relationship with the outbreak of malaria. Malaria is an emerging disease in this province and rainfall has been known as an important meteorological factor in the reconstruction of this disease (Gao et al. 2012).

Malaria is a vector carrying disease created by Plasmodium species and rapidly spread due to climate change. People in developing countries are probably more affected by the impact of the climate change on the spread of malaria. Many of these countries are in ideal geographical places for the outbreak of malaria and have poor health infrastructures to cope with the outbreak of this disease. Therefore, the improvement of health networks in developing countries is of great importance and it is necessary to reduce the impacts of global warming so as to prevent the destructive impacts caused by the increased malaria transmission (Wang and Overland 2004).

Conclusion

The rate of annual death caused by malaria is 429,000 across the world; hence, it is necessary to control this disease. WHO follows the prevention and treatment of malaria in the vulnerable regions by the implementation of malaria return project. As such, the access to health care and answer to malaria in the countries with poor healthcare systems is improved. Furthermore, the people and the societies can cooperate to reduce the threat of global warming and prevent malaria from changing into a greater problem by instructing and recognizing the effects of climate change. The transmission of malaria in Iran is related to climatic factors such as temperature, precipitation, and humidity. According to the report of WHO (2017), Iran is at the malaria pre-eradication stage (Barber et al. 2017). However, the present potential impacts of the climate change on malaria is one of the most important objectives of the public health which demands further studies in this area.

References

- Abeku TA, Van Oortmarssen GJ, Borsboom G, De Vlas SJ, Habbema J. Spatial and temporal variations of malaria epidemic risk in Ethiopia: factors involved and implications. Acta Trop. 2003;87:331–340. doi: 10.1016/S0001-706X(03)00123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson PK, Cunningham AA, Patel NG, Morales FJ, Epstein PR, Daszak P. Emerging infectious diseases of plants: pathogen pollution, climate change and agrotechnology drivers. Trends Ecol Evol. 2004;19:535–544. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babaie J, Fatemi F, Ardalan A, Mohammadi H, Soroush M (2014) Communicable diseases surveillance system in east Azerbaijan earthquake: strengths and weaknesses. PLoS Curr 6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Babaie J, Ardalan A, Vatandoost H, Goya MM, Akbarisari A (2015a) Performance assessment of communicable disease surveillance in disasters: a systematic review. PLoS Curr 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Babaie J, Ardalan A, Vatandoost H, Goya MM, Sari AA. Performance assessment of a communicable disease surveillance system in response to the twin earthquakes of east azerbaijan. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2015;9:367–373. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2015.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barati M, Keshavarz-Valian H, Habibi-Nokhandan M, Raeisi A, Faraji L, Salahi-Moghaddam A. Spatial outline of malaria transmission in Iran. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2012;5:789–795. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(12)60145-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barati M, Salahi Mogadam A, Azizi M. Assessment of malaria status in Iran. Paramed Sci Mil Health. 2014;2:9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Barati M, Khoshdel A, Salahi-Moghaddam A. An overview and mapping of anopheles in Iran. Paramed Sci Mil Health. 2015;10:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BE, Rajahram GS, Grigg MJ, William T, Anstey NM. World malaria report: time to acknowledge plasmodium knowlesi malaria. Malar J. 2017;16:135. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1787-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayoh M, Lindsay S. Effect of temperature on the development of the aquatic stages of anopheles gambiae sensu stricto (diptera: culicidae) Bull Entomol Res. 2003;93:375–381. doi: 10.1079/BER2003259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck-Johnson LM, Nelson WA, Paaijmans KP, Read AF, Thomas MB, Bjørnstad ON. The effect of temperature on Anopheles mosquito population dynamics and the potential for malaria transmission. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e79276. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck-Johnson LM, Nelson WA, Paaijmans KP, Read AF, Thomas MB, Bjørnstad ON. The importance of temperature fluctuations in understanding mosquito population dynamics and malaria risk. Open Sci. 2017;4:160969. doi: 10.1098/rsos.160969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi P, Tong S, Donald K, Parton KA, Ni J. Climatic variables and transmission of malaria: a 12-year data analysis in Shuchen County, China. Public Health Rep. 2003;118:65. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50218-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouma M, Van Der Kaay H. Epidemic malaria in India and the El Nino southern oscillation. Lancet. 1994;344:1638–1639. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)90432-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caminade C, Kovats S, Rocklov J, Tompkins AM, Morse AP, Colón-González FJ, Stenlund H, Martens P, Lloyd SJ. Impact of climate change on global malaria distribution. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:3286–3291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302089111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Change IC (2007) The fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change, Geneva, Switzerland

- Epstein PR. Is global warming harmful to health? Sci Am. 2000;283:50–57. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0800-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein PR. Climate change and emerging infectious diseases. Microbes Infect. 2001;3:747–754. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01429-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein PR, Diaz HF, Elias S, Grabherr G, Graham NE, Martens WJ, Mosley-Thompson E, Susskind J. Biological and physical signs of climate change: focus on mosquito-borne diseases. Bull Am Meteor Soc. 1998;79:409–417. doi: 10.1175/1520-0477(1998)079<0409:BAPSOC>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Floor WM. Public health in Qajar Iran. Washington: Mage Publishers; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gao H-W, Wang L-P, Liang S, Liu Y-X, Tong S-L, Wang J-J, Li Y-P, Wang X-F, Yang H, Ma J-Q. Change in rainfall drives malaria re-emergence in Anhui Province, China. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43686. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haghdoost A. Assessment of seasonal and climatic effects on the incidence and species composition of malaria by using GIS methods. London: University of London; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hales S, De Wet N, Maindonald J, Woodward A. Potential effect of population and climate changes on global distribution of dengue fever: an empirical model. Lancet. 2002;360:830–834. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09964-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halimi M, Delavari M, Takhtardeshir A. Survey of climatic condition of Malaria disease outbreak in Iran using GIS. J Sch Public Health Inst Public Health Res. 2013;10:41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Halimi M, Farajzadeh M, Delavari M, Bagheri H. Climatic Survey of Malaria Incidence in Iran during 1971–2005. J Sch Public Health Inst Public Health Res. 2014;12:1–11. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120100001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halimi M, Zarei Cheghabalehi Z, Jafari Modrek M. Impact of El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) on Annual Malaria Occurrence in Iran. Iran J Health Environ. 2016;9:369–382. [Google Scholar]

- Holakouie Naieni K, Nadim A, Moradi G, Teimori S, Rashidian H, Kandi Kaleh M. Malaria epidemiology in Iran from 1941 to 2006. J Sch Public Health Inst Public Health Res. 2012;10:77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton J, Firor J. Global warming: the complete briefing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Huang F, Zhou S, Zhang S, Wang H, Tang L. Temporal correlation analysis between malaria and meteorological factors in Motuo County, Tibet. Malar J. 2011;10:54. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadgal KM, Zareban I, Alizadeh siouki H, Sepehrvand N. The Epidemiological features of Malaria in Konarak, Iran (2007–2011) J Torbat Heydariyeh University Med Sci. 2014;2:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y-M, Park J-W, Cheong H-K. Estimated effect of climatic variables on the transmission of Plasmodium vivax malaria in the Republic of Korea. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:1314. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovats R, Campbell-Lendrum D, Mcmichel A, Woodward A, Cox JSH. Early effects of climate change: do they include changes in vector-borne disease? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356:1057–1068. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovats RS, Bouma MJ, Hajat S, Worrall E, Haines A. El Niño and health. Lancet. 2003;362:1481–1489. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14695-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn KG, Campbell-Lendrum DH, Armstrong B, Davies CR. Malaria in Britain: past, present, and future. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100:9997–10001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1233687100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Reddy NNR. Factors affecting malaria disease transmission and incidence: a special focous on Visakhapatnam district. Int J Sci Res. 2014;5:312–317. [Google Scholar]

- Lardeux FJ, Tejerina RH, Quispe V, Chavez TK. A physiological time analysis of the duration of the gonotrophic cycle of Anopheles pseudopunctipennis and its implications for malaria transmission in Bolivia. Malar J. 2008;7:141. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindblade KA, Walker ED, Onapa AW, Katungu J, Wilson ML. Highland malaria in Uganda: prospective analysis of an epidemic associated with El Nino. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999;93:480–487. doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(99)90344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay SW, Bødker R, Malima R, Msangeni HA, Kisinza W. Effect of 1997–98 EI Niño on highland malaria in Tanzania. Lancet. 2000;355:989–990. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)90022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabaso ML, Sharp B, Lengeler C. Historical review of malarial control in southern African with emphasis on the use of indoor residual house-spraying. Tropical Med Int Health. 2004;9:846–856. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens W, Niessen LW, Rotmans J, Jetten TH, Mcmichael AJ. Potential impact of global climate change on malaria risk. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103:458. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills JN, Gage KL, Khan AS. Potential influence of climate change on vector-borne and zoonotic diseases: a review and proposed research plan. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:1507. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadkhani M, Khanjani N, Bakhtiari B, Sheikhzadeh K. The relation between climatic factors and malaria incidence in Kerman, South East of Iran. Parasite Epidemiol Control. 2016;1:205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.parepi.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moradi A, Akhtarkavan M, Ghiasvand J, Akhtarkavan H. Assessment of direct adverse impacts of climate change on Iran. earth. 2008;11:16. [Google Scholar]

- Mozafari GA, Mostofialmammaleki R. Bioclimatic analysis of the malaria disease outbreak in Chabahar city. Geographic space. 2012;12:21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffari GA, Hashemi A, Safarpour F. The effect of southern oscillation on malaria disease in Iran with emphasis on the town of Chabahar. J Arid Reg Geogr Stud. 2011;1:53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ostfeld RS, Brunner JL. Climate change and Ixodes tick-borne diseases of humans. Philos Trans R Soc B. 2015;370:20140051. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry M, Canziani O, Palutikof J, Van Der Linden PJ, Hanson CE. Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Patz JA, Campbell-Lendrum D, Holloway T, Foley JA. Impact of regional climate change on human health. Nature. 2005;438:310–317. doi: 10.1038/nature04188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piao S, Ciais P, Huang Y, Shen Z, Peng S, Li J, Zhou L, Liu H, Ma Y, Ding Y. The impacts of climate change on water resources and agriculture in China. Nature. 2010;467:43–51. doi: 10.1038/nature09364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raeisi A, Nikpoor F, Ranjbar Kahkha M, Faraji L. The trend of Malaria in IR Iran from 2002 to 2007. Hakim Res J. 2009;12:35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi D, Morianzadeh J. Analysis of the impact climate and ENSO on the malaria in Kerman province. J Nat Environ Hazards. 2016;5:17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Rodó X, Pascual M, Doblas-Reyes FJ, Gershunov A, Stone DA, Giorgi F, Hudson PJ, Kinter J, Rodríguez-Arias M-À, Stenseth NC. Climate change and infectious diseases: Can we meet the needs for better prediction? Clim Change. 2013;118:625–640. doi: 10.1007/s10584-013-0744-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salahimoghadam A, Khoshdel A, Barati M, Sedaghat MM. An overview and mapping of Malaria and its vectors in Iran. Bimon J Hormozgan Univ Med Sci. 2014;18:428–440. [Google Scholar]

- Salahi-Moghaddam A, Khoshdel A, Dalaei H, Pakdad K, Nutifafa GG, Sedaghat MM. Spatial changes in the distribution of malaria vectors during the past 5 decades in Iran. Acta Trop. 2017;166:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shemshad K, Oshaghi M, Yaghoobi-Ershadi M, Vatandoost H, Abaie M, Zarei Z, Jedari M. Morphological and molecular characteristics of malaria vector Anopheles superpictus populations in Iran. Tehran Univ Med J TUMS Publ. 2007;65:6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR, Corvalán CF, Kjellstrom T. How much global ill health is attributable to environmental factors? Epidemiol Baltim. 1999;10:573–584. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199909000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soleimani Ahmadi M, Vatandoost H, Shaeghi M, Raeisi A, Abedi F, Eshraghian MR, Aghamolaei T, Madani AH, Safari R, Jamshidi M, Alimorad A. Effects of educational intervention on long-lasting insecticidal nets use in a malarious area, southeast Iran. Acta Med Iran. 2012;50:279–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teklehaimanot HD, Lipsitch M, Teklehaimanot A, Schwartz J. Weather-based prediction of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in epidemic-prone regions of Ethiopia I. Patterns of lagged weather effects reflect biological mechanisms. Malar J. 2004;3:41. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-3-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trenberth KE. Climate variability and global warming. Science. 2001;293:48–49. doi: 10.1126/science.293.5527.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Overland JE. Detecting Arctic climate change using Köppen climate classification. Clim Change. 2004;67:43–62. doi: 10.1007/s10584-004-4786-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wangdi K, Singhasivanon P, Silawan T, Lawpoolsri S, White NJ, Kaewkungwal J. Development of temporal modelling for forecasting and prediction of malaria infections using time-series and ARIMAX analyses: a case study in endemic districts of Bhutan. Malar J. 2010;9:251. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2005) Using climate to predict infectious disease epidemics/Communicable Diseases Surveillance and Response, Protection of the Human Environment, Roll Back Malaria

- WHO (2015) World malaria report 2015. World Health Organization

- WHO (2017) World malaria report 2017. World Health Organization

- Wu X, Tian H, Zhou S, Chen L, Xu B. Impact of global change on transmission of human infectious diseases. Sci China Earth Sci. 2014;57:189–203. doi: 10.1007/s11430-013-4635-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Lu Y, Zhou S, Chen L, Xu B. Impact of climate change on human infectious diseases: empirical evidence and human adaptation. Environ Int. 2016;86:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeryan M, Basseri HR, Hanafi-Bojd AA, Raeisi A, Edalat H, Safari R. Bio-ecology of malaria vectors in an endemic area, Southeast of Iran. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2016;9:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtm.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Bi P, Hiller JE. Meteorological variables and malaria in a Chinese temperate city: a twenty-year time-series data analysis. Environ Int. 2010;36:439–445. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]