Abstract

Background: Hispanic Americans consistently exhibit an intergenerational increase in the prevalence of many noncommunicable chronic physical and mental disorders.

Methods: We review and synthesize evidence suggesting that a constellation of prenatal and postnatal factors may play crucial roles in explaining this trend. We draw from relevant literature across several disciplines, including epidemiology, anthropology, psychology, medicine (obstetrics, neonatology), and developmental biology.

Results: Our resulting model is based on evidence that among women, the process of postmigration cultural adjustment (i.e., acculturation) is associated, during pregnancy and after delivery, with psychological and behavioral states that can affect offspring development in ways that may alter susceptibility to noncommunicable chronic disease risk in subsequent-generation Hispanic Americans. We propose one integrated process model that specifies the biological, behavioral, psychological, and sociocultural pathways by which maternal acculturation may influence the child's long-term health. We synthesize evidence from previous studies to describe how acculturation among Hispanic American mothers is associated with alterations to the same biobehavioral systems known to participate in the processes of prenatal and postnatal developmental programming of disease risk. In this manner, we focus on the concepts of biological and cultural mother-to-child transmission across the prenatal and postnatal life phases. We critique and draw from previous hypotheses that have sought to explain this phenomenon (of declining health across generations). We offer recommendations for examining the transgenerational effects of acculturation.

Conclusion: A life course model with a greater focus on maternal health and well-being may be key to understanding transgenerational epidemiological trends in minority populations, and interventions that promote women's wellness may contribute to the elimination or reduction of health disparities.

Keywords: : acculturation, prenatal, postnatal, transgenerational

Introduction

Various immigrant populations across the world appear to exhibit an inverse relationship between health and duration of residence in their host country. Much of this research has focused on Hispanic immigrants to the United States, the country's largest ethnic minority group.1 Hispanic Americans have been observed to exhibit declining health with increasing length of stay and later-generation status in the United States, often despite improvement in socioeconomic conditions and increased access to healthcare.2,3 This trend, sometimes referred to as an “immigrant paradox,”4–6 has been attributed to the detrimental effects of acculturation on various psychological and behavioral processes and their downstream impact on biology and health.7 Although this explanation may help to clarify why health declines with length of stay, it fails to address the transgenerational effect on health.

We propose a novel framework to examine this transgenerational phenomenon, based on evidence that among women, acculturation is related to various psychological, behavioral, and biological states and processes during pregnancy and the postpartum period that may, in turn, affect offspring development in ways that produce poorer health in subsequent-generation Hispanic Americans. We take into account these physiological, psychological, and behavioral mechanisms to offer an integrated process model that delineates the multifarious pathways by which acculturation may affect health across generations. Our perspective brings together the concepts of biological and cultural mother-to-child transmission across the prenatal and postnatal life phases.

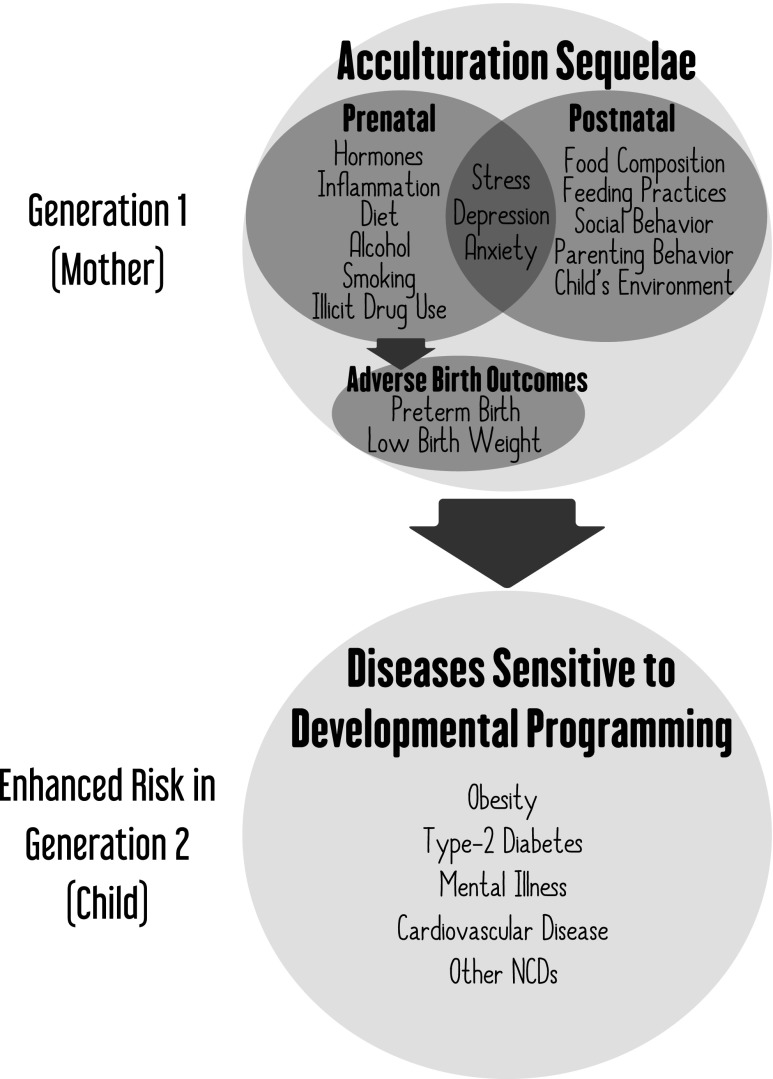

We describe how acculturation among Hispanic American mothers is associated with alterations to the same biobehavioral systems that are known to affect prenatal and postnatal programming of disease risk for the same conditions whose risk has been observed to amplify across generations of Hispanic Americans (Fig. 1). We describe the scientific justification for this model, present evidence in support of its plausibility, and critique alternative hypotheses. Although we apply our model to describe Hispanic Americans as a whole, we acknowledge that there are different subpopulations within the Hispanic American population with variation in acculturative experiences.

FIG. 1.

Diagram depicting the process by which maternal acculturation may affect child health via developmental programming. The observed sequelae of acculturation among Hispanic Americans are the same constructs known to participate in the processes of prenatal and postnatal developmental programming of disease risk. The conditions with enhanced incidence among second-generation Hispanic Americans are the same conditions known to be influenced by developmental programming. Adverse birth outcomes may themselves be acculturation sequelae or they may be associated with acculturation's prenatal correlates, e.g., prenatal stress.

Acculturation and health are multifaceted, multidirectional dynamic constructs.8,9 In this study, we focus on those aspects of acculturation that have been demonstrated to detrimentally affect health across generations, while acknowledging that not all aspects of acculturation are harmful for all health-related outcomes. We use the terms “acculturation” to describe the process of cultural adjustment in immigrant populations in response to contact with the majority culture, “acculturative stress” to denote the negative psychosocial impact of adopting a new culture,10 “first generation” and “immigrant” to refer to individuals who migrate at any age of their lifetime, “second generation” to describe the offspring of immigrants, and “later generations” or “native born” to describe all generations subsequent to the immigrant generation, inclusive of second generation, third generation, and so forth.

Critique of Alternative Hypotheses

Worse health among U.S.-born Hispanics compared to foreign-born (or Puerto Rico-born) Hispanics has been reported most widely for cardiovascular disease,11 mental illness,12 obesity,13 diabetes,14 and adverse birth outcomes.15,16 Before articulating our model to explain this trend, we describe the previously proposed hypothesis that U.S.-born compared to foreign-born Hispanic Americans exhibit poorer health because they suffer from (1) the loss of “cultural buffering,” i.e., the loss of the social support and healthy behaviors associated with traditional Hispanic culture, (2) the adoption of unhealthy American behaviors,17 (3) the stress involved in cultural conversion, and (4) encountering greater degrees of racism/discrimination.18 We argue that evidence suggests that these four phenomena fail to adequately explain poorer health in second-generation compared to first-generation Hispanic Americans. (1) A national survey of 49,000 households found that differences in cultural and social buffering did not account for differences in health or mortality profiles between U.S.-born and foreign-born Hispanic Americans.19,20 (2) For unhealthy behaviors, several studies reporting transgenerational health deterioration in Hispanic Americans find that differences in health between immigrants and later generation individuals persist even after adjusting for health-related behaviors.15,21,22 (3) For acculturative stress, evidence suggests that it is greater among immigrants than among later generation individuals. The direction of change across generations is in direct opposition to changes in health status. For instance, in a multicultural, multiethnic undergraduate cohort in the United States, acculturative stress levels were higher among immigrant compared to later-generation students.23 The observation that acculturative stress is more potent in foreign-born than U.S.-born individuals suggests that it is unlikely to fully explain the tendency of U.S.-born individuals to exhibit poorer health than their foreign-born counterparts. (4) For racism/discrimination, in a cohort of 3,000 Mexican Americans in California, perceived discrimination scores were higher among Mexico-born than U.S.-born individuals and higher among Mexico-educated compared to U.S.-educated individuals.24 Summarily, evidence strongly suggests that the prevailing models alone are insufficient for explaining the transgenerational decline in health among Hispanic Americans.

We highlight the strength of the prevailing paradigm to explain declining health within the immigrant generation of Hispanic Americans,2,3,25–29 particularly the detrimental effect of acculturative stress on mental health among Hispanic immigrants.24,30–34 Our model builds upon and utilizes the evidence and concepts from these previous studies to propose an improved framework for understanding transgenerational epidemiological trends by integrating the principles of biocultural transgenerational transmission.

Biological Mechanisms of Mother-to-Child Transmission of Disease Risk

Immigrants to the United States often exhibit increasing psychosocial stress, which can influence an individual's health through chronic activation of stress-related endocrine, immune, and metabolic physiology. Increased stress can also lead to the enhancement of unhealthy behaviors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and illicit drug use.35,36 For a woman who becomes pregnant, such alterations in her stress physiology can influence her gestational physiology,37 including changes to the biochemical conditions of the womb (hereafter “intrauterine environment”) that, in turn, impact the developmental trajectories of the embryo/fetus. Many traits that determine postnatal health are shaped by the intrauterine environment. Links have been observed between maternal prenatal conditions and offspring postnatal metabolic function,38 immune function,39 and stress physiology.40,41 In addition, during the postnatal phase of life, infant developmental trajectories are responsive to concurrent maternal psychology, parenting behavior, and the composition and pattern of feeding.42 We argue that a mother's experience of acculturation may affect her antepartum and postpartum psychology, behavior, and feeding practices in ways that ultimately influence her child's development of health-related traits. Through these prenatal and postnatal processes, the U.S.-born child of an immigrant may be born with predispositions to noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) in adulthood. Each of the concepts that make up this theoretical framework is described in more detail below.

Our model is based on the phenomenon of developmental programming of health and disease risk. Extensive reviews on this topic can be found.43 For many traits related to health, such as metabolism, brain structure and function, and reactivity to stress, genetic makeup does not precisely specify how the trait will manifest. For these complex traits, a wide range of possible phenotypes may emerge from a specific genotype. During sensitive periods of life, particularly the prenatal period, biochemical cues in the intrauterine and maternal compartments guide developmental processes and determine phenotypic specificity of form and function.44 This process of phenotypic plasticity is an evolutionarily adaptive feature of developmental biology.

For traits that are primarily specified during prenatal life, the embryo/fetus seeks and responds to signals in the intrauterine environment that steer the path of development. While these traits may be plastic during prenatal life, the phenotype exhibited at the time of birth may be relatively stable across the rest of the life span. The relationship between a mother and her developing fetus is biologically intimate, and a mother's psychology, health, and environment may influence gestational physiology in ways that alter fetal developmental trajectories.45,46 Any aspect of the mother's life that affects her physiology during pregnancy has the potential to transmit differential signals to the developing fetus and, thereby, play a role in shaping offspring traits.

Complex traits are also influenced by the postnatal environment, and the effects of many postnatal factors are conditioned, in part, on the prior effects of prenatal factors on these same traits (or their antecedents). As an example, for various aspects of brain function, there are key phases of development that occur postnatally, particularly during infancy. During these life phases, a mother influences developmental trajectories of her child's traits via transmission of the constituents of breast milk,47 skin-to-skin contact (inducing neuroendocrine responses, as well as microbial transmission),48 behavior, social interaction, and shaping the child's physical environment.49 Various aspects of these exposures may act as cues that guide development of plastic traits during infancy.

The process of developmental programming has important implications for health and disease in adulthood in direct and indirect ways. Early-life shaping of plastic traits directly involved in disease etiology, such as glucose metabolism, can directly affect disease propensity in adulthood, such as risk of type-2 diabetes mellitus.50 Indirectly, developmental programming of certain traits can modify susceptibility to disease-causing agents encountered subsequently over the life course. In other words, developmental programming shapes traits that determine susceptibility to disease or how individuals psychobiologically respond to the exposures they encounter in their lives. For example, an individual may be prenatally exposed to metabolic conditions such as hyperglycemia that result in adipocyte overgrowth and insulin and leptin resistance, which lead to enhanced postnatal predisposition for obesity.51 However, the condition of obesity can only occur if the individual is subsequently exposed to an obesogenic diet. For a further example, individuals prenatally exposed to high levels of maternal psychosocial stress, depression, and anxiety exhibit increased behavioral and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) stress reactivity during infancy52 and early and late childhood.53,54 It is important to emphasize that prenatal programming affecting susceptibility to certain disorders does not rule out the role of subsequent exposures in disease etiology. Exposures and experiences encountered by the offspring during her/his subsequent life course interact with early-life programming influences to determine disease propensity. For example, acculturative stress in adolescents has been associated with mental health problems,55 but this does not rule out the possibility that early-life exposures moderate sensitivity to the detrimental consequences of acculturative stress. In this way, our intergenerational model complements and adds relief to other models for understanding how acculturation affects health. Relatedly, exposure to teratogens during sensitive periods of development, as a result of poor health behaviors (e.g., smoking and drinking alcohol) or exposure to environmental toxins due to suboptimal housing or neighborhood conditions, can have profound consequences.56 Teratogenic insult results in different malformations and abnormalities, depending on the developmental processes underway at the time of exposure. For example, infants who were prenatally exposed to maternal binge alcohol consumption at different weeks of gestation exhibited differential facial malformations at birth depending on the gestational week of exposure.57

Through these direct and indirect pathways, early-life experiences can influence propensity for disease throughout the life course, i.e., the concept of developmental origins of health and disease.58,59 The types of maternal conditions and cues that have been most robustly demonstrated to affect health and disease propensity are psychosocial stress,60 depression, endocrinology,60 inflammation,61 and diet,62 as well as the toxic exposures of alcohol,63 smoking,64 and illicit drugs.65 The types of diseases that have been most robustly demonstrated to be influenced by developmental programming are obesity, type-2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, mental illness, cardiovascular disease, and other NCDs.50 Notably, the health disorders whose prevalence corresponds to generation status in Hispanic Americans are precisely the same disorders that have been robustly associated with developmental programming (Fig. 1). Adverse birth outcomes play a particularly important role in our model. Although they haven't previously been described as a mediator between acculturation in one generation and health in the next generation, we argue that this is plausible because adverse birth outcomes are associated with the detrimental sequelae of acculturation (e.g., depression66 and psychosocial stress67). Previous studies have, indeed, described a direct relationship between acculturation and adverse birth outcomes,68 but only interpreted this as a reflection of maternal health, rather than extending this idea to second-generation epidemiology. For this reason, we depict adverse birth outcomes as both a category and a consequence of acculturation sequelae (Fig. 1).

Evidence that Maternal Acculturation Affects Offspring Prenatal and Postnatal Development and Health

As discussed above, during the prenatal phase of life, a mother's psychology, behavior, and physical environment influence her own biology in ways that can affect her gestational biology, thereby influencing her child's biological development and lifelong disease susceptibility. During the postnatal phase of life, a mother's psychology and behavior can influence her child's development and health via feeding practices and parenting behavior. Thus, it is possible that maternal acculturation affects child health through both prenatal and postnatal processes, and acculturation's prenatal influences could be modified by postnatal factors.

Maternal acculturation and prenatal biological influences on child health

Several studies have evinced that the relationship between maternal acculturation and child outcomes may be mediated by features of gestational physiology. Specifically, hormones and cytokines may reflect women's acculturation experiences and enact alterations to offspring development. For example, prenatal maternal cortisol patterns have been identified as a potential mediator between acculturation and birth weight.44 In pregnant Hispanic women, English proficiency has also predicted levels of placental corticotrophin-releasing hormone, a stress responsive peptide that is released into maternal and fetal circulation during pregnancy and has been associated with preterm birth.69 Higher levels of cortisol and acculturation and lower levels of family cohesion have been associated with increased risk of preterm birth in Mexican American women.70 In another study of pregnant Hispanic women, higher levels of English proficiency was associated with an increased risk of preterm birth, and this association was mediated by a decrease in progesterone/estriol ratio.71

The observed associations between acculturation and gestational biology support the plausibility of intergenerational transmission of acculturation's effects by identifying concrete mechanisms of prenatal transmission. Further examples of correlations between acculturation and biomarkers in nonpregnant populations11,72–74 suggest that other molecules and physiological systems should also be investigated in pregnancy.

Maternal acculturation and prenatal behavioral influences on child health

There is already compelling evidence that among pregnant Hispanic women, acculturation and the development of associated stress is associated with particular patterns of behavioral and psychosocial states, which could affect gestational biology. Greater degree of acculturation among Hispanic pregnant women has been associated with poorer diet,75 more alcohol,76,77 cigarette smoking,75,77,78 marijuana,77 and other substance abuse.76,79 Spanish-speaking Mexican-American mothers exhibit fewer mental health problems during pregnancy compared with bilingual and English-speaking Mexican American mothers,78 and greater degree of acculturation is associated with greater degree of psychosocial stress and negative feelings among pregnant Hispanic women.75,76,80,81 These patterns suggest the possibility that the offspring of more acculturated mothers may have worse health outcomes due to the detrimental effects of poor diet (e.g., metabolic dysregulation), toxins (e.g., oxidative damage), and psychological stress (e.g., high concentrations of stress hormones) on fetal development.

Maternal acculturation and postnatal behavioral influences on child health

Maternal acculturation may also exert effects upon child health during the early postnatal period of the child's life, via breastfeeding and other aspects of infant diet, as well as via parenting practices. Whether or not and for how long an infant is breastfed have lifelong effects on the individuals' health.82 Hispanic mothers who retain a more traditional cultural orientation exhibit higher breastfeeding rates.83–85 Mexican American women who practice more traditional customs related to childbirth were more likely to breastfeed,85 and Mexican American women born in Mexico were more likely to breastfeed than those born in the United States.84

Maternal acculturation may affect child health through parenting behaviors, which can impact child psychology and child behavior. For example, feeding practices during an individual's infancy and early childhood have lifelong effects on the individuals' health, food preferences, and behaviors.86–88 One study found that less acculturated Mexican American mothers' feeding strategies were advantageous compared to more acculturated peers, with less acculturated mothers less likely to use authoritarian child feeding practices.89 However, potentially detrimental aspects of less acculturated maternal feeding strategies have also been observed, including being more likely to involve bribes, threats, and punishments and less likely to give vitamins.90

More acculturated Hispanic mothers have also been observed to exhibit more inconsistent discipline and more parenting monitoring compared with their more acculturated counterparts,91 which mediated acculturation's positive correlation with child delinquency.91 A large national survey study found that less acculturated (compared with more acculturated) Hispanic mothers exhibited a more positive attitude toward parenting, specifically endorsing the idea that parenting is worth it despite the costs and work.77

However, other acculturation-related changes in mothering behavior may be beneficial for child development. In various studies, being more acculturated has been positively associated with greater permission of child autonomy,92 greater awareness of children's needs, child-centric family dynamics, realistic child expectations,78 more maternal knowledge about child development,93 teaching behaviors, including increased use of inquiry and praise,94 increase in school involvement,95 less gender role socialization,96 and decreased son preference.97

Health-related parenting behaviors have been understudied, and results have thus far been inconsistent. One report suggests that more acculturated Hispanic women were less likely to immunize their children,98 whereas another suggests that women who were more acculturated were more likely to utilize medical services for their children.99 While the directionality of effects is a complex issue that requires further study, it is evident that maternal acculturation is associated with maternal prenatal and postnatal behaviors and psychological states that could affect children's physiological development.

Maternal acculturation's association with child health outcomes

Health status in ethnic minority children has, previously, been attributed to the child's—rather than mother's—acculturation status. For example, obesogenic preferences and behaviors were related to acculturation measured in Asian and Hispanic American 6th and 7th graders,100 child nativity was related to obesity rates in a multiethnic sample of U.S. 10–17 year olds, and greater acculturation was associated with higher levels of markers of subclinical cardiovascular disease among White, Chinese, Black, and Hispanic American children.101

We argue that maternal acculturation may affect child health regardless of the child's degree of acculturation. Substantiation of the possibility that maternal acculturation affects child health comes from evidence that maternal acculturation has been associated with birth outcomes and children's mental and physical health. Maternal acculturation's relationship with the child's health at birth indicates not only that acculturation's health effects maybe transmitted across generations, but also that such transmission may begin as early as during the child's intrauterine period of life. A mother's greater degree of acculturation102 and later generation status16,102–106 have been associated with her child's greater risk of low birth weight, small for gestational age, preterm birth, stillbirth, and neonatal mortality. Maternal acculturation's relationship with child mental health indicates the possibility that an effect can be transmitted across generations. Among Hispanic Americans, maternal acculturation has been associated with children's depressive symptoms, although opposing effects have been demonstrated,107 and maternal acculturation was not related to children's anxiety.108

Maternal acculturation's relationship with child physical health provides compelling evidence that acculturation in one generation can negatively affect health in a subsequent generation. Among Soviet Jewish refugees in southern Israel, mothers' greater duration of residence in Israel was associated with greater prevalence of overweight and obesity in their children ages 4–7 years,109 suggesting the possibility of a similar intergenerational effect of maternal acculturation on child obesity risk across ethnicities and nationalities. One study found larger triceps skinfold thickness in preschooler children of more acculturated Mexican American mothers,90 although no such effect was found on child weight, BMI, or obesity in that study and others.90,110 Mexican American mothers who reported higher prenatal stress and lower partner support during pregnancy had infants with greater physiological stress reactivity at 6 weeks of age.111 While this effect was not measured with relation to acculturation, acculturation has a demonstrated relationship with prenatal stress and partner support among Mexican Americans.75,81 In a mixed-ethnicity low-socio-economic status cohort, greater degree of maternal acculturation in the immigrant subset of the cohort (77% Latina) was associated with greater asthma symptomology in the children at age three.112

The directionality of maternal acculturation's association with child health varies between studies, but the evidence of any correlation suggests the possibility of intergenerational effects whose causal pathways should be further investigated.

Recommended Methods for Examining Transgenerational Effects of Acculturation

To investigate the relationship between acculturation and maternal child health, the acculturation measurement instrument must capture those aspects of acculturation that are most relevant in the context of maternal child health. Studying transgenerational effects of acculturation requires special focus on the mother as a biocultural conduit and connector between generations.

One option would be to develop a new instrument to measure status and changes in cultural attitudes toward motherhood. Acculturation items related to gender roles, motherhood, childbearing, and family norms may change independently from other aspects of acculturation, and therefore, it may be informative to measure a specific motherhood acculturation domain. Relevant sociocultural factors that may change in the transition from traditional Hispanic toward American identity include gender roles, family structure, and social support for mothers. In a small number of studies, gender and familial norms that are different between the United States and Mexico were included as factors in acculturation assessments,83,113–115 but were measured in inconsistent ways that have not been subject to psychometric development and analysis standards. Changes in familism that can occur with acculturation may involve changes in female camaraderie and attitudes toward pregnancy and motherhood.116,117 Religiosity may also be a relevant item to consider, because it has been associated with reproductive health benefits and positive birth outcomes among Mexican Americans.118 In Mexican Catholicism, the Virgin of Guadalupe is a central figure, symbolizing the sanctity of femininity and motherhood,119 potentially affecting psychosocial conditions,120 behaviors, and health during pregnancy. For example, in a study of Mexican American mothers, 25% reported the Virgin of Guadalupe as a direct source of comfort and peace.118 More rigorous work in these domains is needed to further understand which sociocultural factors are relevant in acculturation assessments for studies of transgenerational processes.

An important aspect of acculturative stress is discrimination/racism. Only one study, to our knowledge, has investigated the effect of discrimination-related stressors on birth outcomes in Hispanics. Novak et al. found121 a significantly enhanced incidence of low birth weight among Latina mothers in Iowa after (compared with before) the largest single-site federal immigration raid in U.S. history, which occurred in Iowa. Looking at other ethnic groups, one study in New Zealand found elevated cortisol during late pregnancy among women reporting ethnic discrimination.122 Compared to White pregnant women, African American pregnant women exhibit higher blood pressure across pregnancy123 and a stronger relationship between psychological stress and blood pressure.124 Several studies have produced evidence that among African American pregnant women, perceived racism is positively associated with preterm delivery and low birth weight.125 This evidence suggests that the chronic stress of racial discrimination can influence gestational biology.

A final consideration is that during pregnancy, women become progressively less physiologically responsive to stress.126 This dampening of reactivity has been demonstrated for various aspects of the physiological stress system, including the HPA127 and sympathetic-adrenal-medullary128,129 axes and cardiovascular130,131 responses to stressors. Both psychosocial126 and physiological132 stressors elicit dampened responses in pregnant women. In the nonpregnancy literature, a major avenue by which acculturation exerts its health effects upon individuals is via psychosocial stress (i.e., acculturative stress10). Given the observation that psychosocial stressors elicit different effects during pregnant and nonpregnant states, it is vitally important that acculturation's health effects be specifically investigated in the context of pregnancy.

Concluding Remarks

In sum, acculturation may exert its health effects across generations. The cultural shift from traditional Hispanic to American cultures may involve psychological and health behavior related detriments specific to maternal health and well-being. Maternal acculturation may influence child health through changes in maternal psychobehavioral and biological factors during pregnancy and through changes in maternal psychobehavioral factors during her child's early postnatal life. Health effects in early life may influence the child's long-term health, especially risk of noncommunicable chronic disease.

An appreciation of the possibility that acculturation experiences in one generation may affect disease risk in future generations is critical for public policy. First, our model justifies investment in women and girls' well-being to improve health in immigrant and minority populations. This could include enhancing access to mental health and reproductive medicine resources for females in disadvantaged communities or sponsoring opportunities for greater educational attainment in girls, such as higher-education scholarships. Second, our model highlights the need for culturally sensitive support of perinatal women. Evidence that both prenatal and postnatal behaviors may transmit detrimental consequences of acculturation across generations indicates that expanding women's access to mother-child bonding classes, nutrition education and breastfeeding classes, parenting classes, or other community support could improve population health. It is crucial that community support systems provide culturally relevant resources to support women negotiating multiple cultural identities, to alleviate acculturative stress and reduce exposure to discrimination. Third, our model advocates for diminishing blame on minority populations who may exhibit a higher prevalence of particular chronic diseases. For example, while Hispanic Americans may indeed exhibit increasing rates of obesity and type-2 diabetes mellitus, these are complex conditions whose etiology is determined not only by an individual's conscious behavior but also by prenatal and neonatal exposures that are in turn shaped by broader political economic processes. If Hispanic immigrant women's stresses imposed by structural challenges predispose their U.S.-born children to higher rates of obesity and diabetes, then victim blaming and shaming is rendered less defensible. Both research and intervention could benefit from more focus on immigrant and minority women's well-being and less on individuals' eating and exercise behaviors to address public health crises related to obesity and diabetes. Summarily, our model highlights ways to design efficacious interventions to disrupt the transgenerational cascade of health deterioration among Hispanic Americans by targeting nodes of intergenerational transmission.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by NIH grant National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases award K01 DK105110 to M.F.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.U.S._Census_Bureau. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Sex, Age, Race, and Hispanic Origin for the United States and States: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014. 2017:https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk Accessed October26, 2016

- 2.Kaplan MS, Huguet N, Newsom JT, McFarland BH. The association between length of residence and obesity among Hispanic immigrants. Am J Prev Med 2004;27:323–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abraído-Lanza AF, Chao MT, Florez KR. Do healthy behaviors decline with greater acculturation?: Implications for the Latino mortality paradox. Soc Sci Med 2005;61:1243–1255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Margarita Alegría PD, Glorisa Canino PD, Patrick E. Shrout PD, et al. Prevalence of mental illness in immigrant and non-immigrant U.S. Latino groups. Am J Psychiatry 2008;165:359–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marks AK, Ejesi K, García Coll C. Understanding the U.S. immigrant paradox in childhood and adolescence. Child Dev Perspect 2014;8:59–64 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bacio GA, Mays VM, Lau AS. Drinking initiation and problematic drinking among Latino adolescents: Explanations of the immigrant paradox. Psychol Addict Behav 2013;27:14–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasirye OC, Walsh JA, Romano PS, et al. Acculturation and its association with health-risk behaviors in a rural Latina population. Ethn Dis 2004;15:733–739 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fox M, Thayer Z, Wadhwa PD. Assessment of acculturation in minority health research. Soc Sci Med 2017;176:123–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox M, Thayer Z, Wadhwa PD. Acculturation and health: The moderating role of socio-cultural context. Am Anthropologist 2017;119:405–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berry JW. Acculturative stress. In: Wong P, Wong L, eds. Handbook of multicultural perspectives on stress and coping. Langley, BC: Springer, 2006:287–298 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sundquist J, Winkleby MA. Cardiovascular risk factors in Mexican American adults: A transcultural analysis of NHANES III, 1988–1994. Am J Public Health 1999;89:723–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alegria M, Mulvaney-Day N, Torres M, Polo A, Cao Z, Canino G. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders across Latino subgroups in the United States. Am J Public Health 2007;97:68–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bates LM, Acevedo-Garcia D, Alegria M, Krieger N. Immigration and generational trends in body mass index and obesity in the United States: Results of the National Latino and Asian American Survey, 2002–2003. Am J Public Health 2008;98:70–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmed AT, Quinn VP, Caan B, Sternfeld B, Haque R, Van Den Eeden SK. Generational status and duration of residence predict diabetes prevalence among Latinos: The California Men's Health Study. BMC Public Health 2009;9:392–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guendelman S, Gould JB, Hudes M, Eskenazi B. Generational differences in perinatal health among the Mexican American population: Findings from HHANES 1982–1984. Am J Public Health 1990;80:61–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins JW, Shay DK. Prevalence of low birth weight among Hispanic infants with United States-born and foreign-born mothers: The effect of urban poverty. Am J Epidemiol 1994;139:184–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guendelman S, Abrams B. Dietary intake among Mexican-American women: Generational differences and a comparison with white non-Hispanic women. Am J Public Health 1995;85:20–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gallo LC, Penedo FJ, Espinosa de los Monteros K, Arguelles W. Resiliency in the face of disadvantage: Do Hispanic cultural characteristics protect health outcomes? J Pers 2009;77:1707–1746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter-Pokras O, Zambrana RE, Yankelvich G, Estrada M, Castillo-Salgado C, Ortega AN. Health status of Mexican-origin persons: Do proxy measures of acculturation advance our understanding of health disparities? J Immigr Minor Health 2008;10:475–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palloni A, Arias E. A re-examination of the Hispanic mortality paradox. Center for Demography and Ecology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2003. Working Paper No. 2003-01 https://www.ssc.wisc.edu/cde/cdewp/2003-01.pdf Accessed March24, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hummer RA, Rogers RG, Nam CB, LeClere FB. Race/ethnicity, nativity, and US adult mortality. Soc Sci Quart 1999;80:136–153 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei M, Valdez RA, Mitchell BD, Haffner SM, Stern MP, Hazuda HP. Migration status, socioeconomic status, and mortality rates in Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites: The San Antonio Heart Study. Ann Epidemiol 1996;6:307–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mena FJ, Padilla AM, Maldonado M. Acculturative stress and specific coping strategies among immigrant and later generation college students. Hispanic J Behav Sci 1987;9:207–225 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finch BK, Kolody B, Vega WA. Perceived discrimination and depression among Mexican-origin adults in California. J Health Soc Behav 2000;41:295–313 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho Y, Frisbie WP, Hummer RA, Rogers RG. Nativity, duration of residence, and the health of Hispanic adults in the United States. Int Migr Rev 2004;38:184–211 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuentes-Afflick E, Hessol NA. Acculturation and body mass among Latina women. J Womens Health 2008;17:67–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oza-Frank R, Venkat Narayan K. Effect of length of residence on overweight by region of birth and age at arrival among US immigrants. Public Health Nutr 2010;13:868–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koya DL, Egede LE. Association between length of residence and cardiovascular disease risk factors among an ethnically diverse group of United States immigrants. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:841–846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goel MS, McCarthy EP, Phillips RS, Wee CC. Obesity among US immigrant subgroups by duration of residence. JAMA 2004;292:2860–2867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cervantes RC, Padilla AM, Salgado de Snyder N. The Hispanic stress inventory: A culturally relevant approach to psychosocial assessment. Psychol Assessment 1991;3:438–447 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hovey JD, Magaña C. Acculturative stress, anxiety, and depression among Mexican immigrant farmworkers in the Midwest United States. J Immigr Health 2000;2:119–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hovey JD, Magaña CG. Psychosocial predictors of anxiety among immigrant Mexican migrant farmworkers: Implications for prevention and treatment. Cult Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 2002;8:274–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thoman LV, Surís A. Acculturation and acculturative stress as predictors of psychological distress and quality-of-life functioning in Hispanic psychiatric patients. Hispanic J Behav Sci 2004;26:293–311 [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Snyder VNS, Cervantes RC, Padilla AM. Gender and ethnic differences in psychosocial stress and generalized distress among Hispanics. Sex Roles 1990;22:441–453 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berry JW. Acculturation and adaptation in a new society. Int Migr 1992;30:69–85 [Google Scholar]

- 36.McEwen BS, Seeman T. Protective and damaging effects of mediators of stress: Elaborating and testing the concepts of allostasis and allostatic load. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999;896:30–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soares MJ. The prolactin and growth hormone families: Pregnancy-specific hormones/cytokines at the maternal-fetal interface. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2004;2:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Entringer S. Impact of stress and stress physiology during pregnancy on child metabolic function and obesity risk. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2013;16:320–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Veru F, Laplante DP, Luheshi G, King S. Prenatal maternal stress exposure and immune function in the offspring. Stress 2014;17:133–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thayer ZM, Kuzawa CW. Early origins of health disparities: Material deprivation predicts maternal evening cortisol in pregnancy and offspring cortisol reactivity in the first few weeks of life. Am J Hum Biol 2014;26:723–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kapoor A, Dunn E, Kostaki A, Andrews MH, Matthews SG. Fetal programming of hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal function: Prenatal stress and glucocorticoids. J Physiol 2006;572:31–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thompson RA. Stress and child development. Future Children 2014;24:41–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aiken CE, Ozanne SE. Transgenerational developmental programming. Hum Reprod Update 2014;20:63–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.D'Anna-Hernandez K, Hoffman M, Zerbe G, Coussons-Read M, Ross R, Laudenslager M. Acculturation, maternal cortisol, and birth outcomes in women of Mexican descent. Psychosom Med 2012;74:296–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fox M, Entringer S, Buss C, DeHaene J, Wadhwa PD. Intergenerational transmission of the effects of acculturation on health in Hispanic Americans: A fetal programming perspective. Am J Public Health 2015;105:S409–S423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wadhwa PD. Psychoneuroendocrine processes in human pregnancy influence fetal development and health. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2005;30:724–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feldman R, Eidelman AI. Direct and indirect effects of breast milk on the neurobehavioral and cognitive development of premature infants. Dev Psychobiol 2003;43:109–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feldman R, Rosenthal Z, Eidelman AI. Maternal-preterm skin-to-skin contact enhances child physiologic organization and cognitive control across the first 10 years of life. Biol Psychiatry 2014;75:56–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Champagne FA, Curley JP. How social experiences influence the brain. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2005;15:704–709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barker D. Developmental origins of chronic disease. Public Health 2012;126:185–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang JS, Lee TA, Lu MC. Prenatal programming of childhood overweight and obesity. Matern Child Health J 2007;11:461–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davis EP, Glynn LM, Waffarn F, Sandman CA. Prenatal maternal stress programs infant stress regulation. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2011;52:119–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lupien SJ, McEwen BS, Gunnar MR, Heim C. Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009;10:434–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sandman CA, Davis EP, Buss C, Glynn LM. Exposure to prenatal psychobiological stress exerts programming influences on the mother and her fetus. Neuroendocrinology 2012;95:8–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sirin SR, Ryce P, Gupta T, Rogers-Sirin L. The role of acculturative stress on mental health symptoms for immigrant adolescents: A longitudinal investigation. Dev Psychol 2013;49:736–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Selevan SG, Kimmel CA, Mendola P. Identifying critical windows of exposure for children's health. Environ Health Perspect 2000;108:451–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sawada Feldman H, Lyons Jones K, Lindsay S, et al. Prenatal alcohol exposure patterns and alcohol-related birth defects and growth deficiencies: A prospective study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2012;36:670–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barker DJ, Eriksson JG, Forsen T, Osmond C. Fetal origins of adult disease: Strength of effects and biological basis. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:1235–1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wadhwa PD, Buss C, Entringer S, Swanson JM. Developmental origins of health and disease: Brief history of the approach and current focus on epigenetic mechanisms. Semin Reprod Med 2009;27:358–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cottrell EC, Seckl J. Prenatal stress, glucocorticoids and the programming of adult disease. Front Behav Neurosci 2009;3:19–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Christian LM. Psychoneuroimmunology in pregnancy: Immune pathways linking stress with maternal health, adverse birth outcomes, and fetal development. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2012;36:350–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barker DJ, Godfrey KM, Gluckman PD, Harding JE, Owens JA, Robinson JS. Fetal nutrition and cardiovascular disease in adult life. Lancet 1993;341:938–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hellemans KG, Sliwowska JH, Verma P, Weinberg J. Prenatal alcohol exposure: Fetal programming and later life vulnerability to stress, depression and anxiety disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2010;34:791–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.DiFranza JR, Aligne CA, Weitzman M. Prenatal and postnatal environmental tobacco smoke exposure and children's health. Pediatrics 2004;113:1007–1015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thompson BL, Levitt P, Stanwood GD. Prenatal exposure to drugs: Effects on brain development and implications for policy and education. Nat Rev Neuroscience 2009;10:303–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ruiz RJ, Marti CN, Pickler R, Murphey C, Wommack J, Brown CE. Acculturation, depressive symptoms, estriol, progesterone, and preterm birth in Hispanic women. Arch Womens Ment Health 2012;15:57–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rini CK, Dunkel-Schetter C, Wadhwa PD, Sandman CA. Psychological adaptation and birth outcomes: The role of personal resources, stress, and sociocultural context in pregnancy. Health Psychol 1999;18:333–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Coonrod DV, Bay RC, Balcazar H. Ethnicity, acculturation and obstetric outcomes: Different risk factor profiles in low-and high-acculturation Hispanics and in white non-Hispanics. J Reprod Med 2004;49:17–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ruiz RJ, Dolbier CL, Fleschler R. The relationships among acculturation, biobehavioral risk, stress, corticotropin-releasing hormone, and poor birth outcomes in Hispanic women. Ethn Dis 2006;16:926–932 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ruiz RJ, Pickler RH, Marti CN, Jallo N. Family cohesion, acculturation, maternal cortisol, and preterm birth in Mexican-American women. Int J Womens Health 2013;5:243–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ruiz RJ, Saade GR, Brown CE, et al. The effect of acculturation on progesterone/estriol ratios and preterm birth in Hispanics. Obstet Gynecol 2008;111:309–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Peek MK, Cutchin MP, Salinas JJ, et al. Allostatic load among non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, and people of Mexican origin: Effects of ethnicity, nativity, and acculturation. Am J Public Health 2010;100:940–946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Finch BK, Do DP, Frank R, Seeman T. Could “acculturation” effects be explained by latent health disadvantages among Mexican immigrants? Int Migr Rev 2009;43:471–495 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rodriguez F, Peralta CA, Green AR, López L. Comparison of C-reactive protein levels in less versus more acculturated Hispanic adults in the United States (from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2008). Am J Cardiol 2012;109:665–669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Page RL. Positive pregnancy outcomes in Mexican immigrants: What can we learn? J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2004;33:783–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zambrana RE, Scrimshaw S, Collins N, Dunkel-Schetter C. Prenatal health behaviors and psychosocial risk factors in pregnant women of Mexican origin: The role of acculturation. Am J Public Health 1997;87:1022–1026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Page RL. Differences in health behaviors of Hispanic, White, and Black childbearing women focus on the Hispanic paradox. Hispanic J Behav Sci 2007;29:300–312 [Google Scholar]

- 78.Acevedo MC. The role of acculturation in explaining ethnic differences in the prenatal health-risk behaviors, mental health, and parenting beliefs of Mexican American and European American at-risk women. Child Abuse Negl 2000;24:111–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Heilemann MV, Lee KA, Stinson J, Koshar JH, Goss G. Acculturation and perinatal health outcomes among rural women of Mexican descent. Res Nurs Health 2000;23:118–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fleuriet KJ, Sunil T. Perceived social stress, pregnancy-related anxiety, depression and subjective social status among pregnant Mexican and Mexican American women in South Texas. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2014;25:546–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sherraden MS, Barrera RE. Maternal support and cultural influences among Mexican immigrant mothers. Fam Soc 1996;77:298–312 [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cunningham AS, Jelliffe DB, Patrice Jelliffe E. Breast-feeding and health in the 1980 s: A global epidemiologic review. J Pediatrics 1991;118:659–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kimbro RT, Lynch SM, McLanahan S. The Hispanic paradox and breastfeeding: Does acculturation matter? Evidence from the fragile families study. Bendhiem-Thoman Center for Child Wellbeing, 2004. No 949, Working Papers from Princeton University, Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, Center for Research on Child Wellbeing. http://crcw.princeton.edu/workingpapers/WP04-01-FF-Kimbro.pdf Accessed March24, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 84.Romero-Gwynn E, Carias L. Breast-feeding intentions and practice among Hispanic mothers in southern California. Pediatrics 1989;84:626–632 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.de la Torre A, Rush L. The determinants of breastfeeding for Mexican migrant women. Int Migr Rev 1987;21:728–742 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Carper J, Orlet Fisher J, Birch LL. Young girls' emerging dietary restraint and disinhibition are related to parental control in child feeding. Appetite 2000;35:121–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Birch LL, McPheee L, Shoba B, Steinberg L, Krehbiel R. “Clean up your plate”: Effects of child feeding practices on the conditioning of meal size. Learn Motiv 1987;18:301–317 [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ruel MT, Menon P. Child feeding practices are associated with child nutritional status in Latin America: Innovative uses of the demographic and health surveys. J Nutr 2002;132:1180–1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Birch LL, Marlin DW, Rotter J. Eating as the “means” activity in a contingency: Effects on young children's food preference. Child Dev 1984;55:431–439 [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kaiser LL, Melgar-Quinonez HR, Lamp CL, Johns MC, Harwood JO. Acculturation of Mexican-American mothers influences child feeding strategies. J Am Diet Assoc 2001;101:542–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Samaniego RY, Gonzales NA. Multiple mediators of the effects of acculturation status on delinquency for Mexican American adolescents. Am J Community Psychol 1999;27:189–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zapata JT, Jaramillo PT. Research on the Mexican-American family. J Individ Psychol 1981;37:72–85 [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gutierrez J, Sameroff AJ, Karrer BM. Acculturation and SES effects on Mexican-American parents' concepts of development. Child Dev 1988;59:250–255 [Google Scholar]

- 94.Planos R, Zayas LH, Busch-Rossnagel NA. Acculturation and teaching behaviors of Dominican and Puerto Rican mothers. Hispanic J Behav Sci 1995;17:225–236 [Google Scholar]

- 95.Valdez CR, Mills MT, Bohlig AJ, Kaplan D. The role of parental language acculturation in the formation of social capital: Differential effects on high-risk children. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2013;44:334–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Raffaelli M, Ontai LL. Gender socialization in Latino/a families: Results from two retrospective studies. Sex Roles 2004;50:287–299 [Google Scholar]

- 97.Unger JB, Molina GB. Desired family size and son preference among Hispanic women of low socioeconomic status. Fam Plann Perspect 1997;29:284–287 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Anderson LM, Wood DL, Sherbourne CD. Maternal acculturation and childhood immunization levels among children in Latino families in Los Angeles. Am J Public Health 1997;87:2018–2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Clark L. Mexican-origin mothers' experiences using children's health care services. West J Nurs Res 2002;24:159–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Unger JB, Reynolds K, Shakib S, Spruijt-Metz D, Sun P, Johnson CA. Acculturation, physical activity, and fast-food consumption among Asian-American and Hispanic adolescents. J Community Health 2004;29:467–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lutsey PL, Diez Roux AV, Jacobs DR Jr., et al. Associations of acculturation and socioeconomic status with subclinical cardiovascular disease in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Public Health 2008;98:1963–1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Scribner R, Dwyer JH. Acculturation and low birthweight among Latinos in the Hispanic HANES. Am J Public Health 1989;79:1263–1267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ventura SJ, Taffel SM. Childbearing characteristics of US-and foreign-born Hispanic mothers. Public Health Rep 1985;100:647–652 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cervantes A, Keith L, Wyshak G. Adverse birth outcomes among native-born and immigrant women: Replicating national evidence regarding Mexicans at the local level. Matern Child Health J 1999;3:99–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Acevedo-Garcia D, Soobader M-J, Berkman LF. Low birthweight among US Hispanic/Latino subgroups: The effect of maternal foreign-born status and education. Soc Sci Med 2007;65:2503–2516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Flores ME, Simonsen SE, Manuck TA, Dyer JM, Turok DK. The “Latina epidemiologic paradox”: Contrasting patterns of adverse birth outcomes in US-born and foreign-born Latinas. Womens Health Issues 2012;22:e501–e507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dumka LE, Roosa MW, Jackson KM. Risk, conflict, mothers' parenting, and children's adjustment in low-income, Mexican immigrant, and Mexican American families. J Marriage Family 1997;59:309–323 [Google Scholar]

- 108.Pienkowski M. The impact of maternal acculturation, youth age, sex and anxiety sensitivity on anxiety symptoms in hispanic youth. Florida International University Digital Commons: Department of Psychology, Florida International University, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kaufman-Shriqui V, Fraser D, Friger M, et al. Factors associated with childhood overweight and obesity among acculturated and new immigrants. Ethn Dis 2013;23:329–335 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sussner KM, Lindsay AC, Peterson KE. The influence of maternal acculturation on child body mass index at age 24 months. J Am Diet Assoc 2009;109:218–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Luecken LJ, Lin B, Coburn SS, MacKinnon DP, Gonzales NA, Crnic KA. Prenatal stress, partner support, and infant cortisol reactivity in low-income Mexican American families. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013;38:3092–3101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Abdou CM, Dominguez TP, Myers HF. Maternal familism predicts birthweight and asthma symptoms three years later. Soc Sci Med 2013;76:28–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Marin BV, Tschann JM, Gomez CA, Kegeles SM. Acculturation and gender differences in sexual attitudes and behaviors: Hispanic vs non-Hispanic white unmarried adults. Am J Public Health 1993;83:1759–1761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Phinney JS, Flores J. “Unpackaging” acculturation aspects of acculturation as predictors of traditional sex role attitudes. J Cross Cult Psychol 2002;33:320–331 [Google Scholar]

- 115.Marin G, Sabogal F, Marin BV, Otero-Sabogal R, Perez-Stable EJ. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hispanic J Behav Sci 1987;9:183–205 [Google Scholar]

- 116.Cuéllar I, Arnold B, Gonzalez G. Cognitive referents of acculturation: Assessment of cultural constructs in Mexican Americans. J Commun Psychol 1995;23:339–356 [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lopez-Class M, Castro FG, Ramirez AG. Conceptions of acculturation: A review and statement of critical issues. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:1555–1562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Magana A, Clark NM. Examining a paradox: Does religiosity contribute to positive birth outcomes in Mexican American populations? Health Educ Behav 1995;22:96–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Rodriguez J. Our lady of Guadalupe: Faith and empowerment among Mexican-American women. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zavella P, Castañeda X. Sexuality and risks: Gendered discourses about virginity and disease among young women of Mexican origin. Latino Studies 2005;3:226–245 [Google Scholar]

- 121.Novak NL, Geronimus AT, Martinez-Cardoso AM. Change in birth outcomes among infants born to Latina mothers after a major immigration raid. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:839–849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Thayer ZM, Kuzawa CW. Ethnic discrimination predicts poor self-rated health and cortisol in pregnancy: Insights from New Zealand. Soc Sci Med 2015;128:36–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Hilmert CJ, Schetter CD, Dominguez TP, et al. Stress and blood pressure during pregnancy: Racial differences and associations with birthweight. Psychosomat Med 2008;70:57–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.McCubbin JA, Lawson EJ, Cox S, Sherman JJ, Norton JA, Read JA. Prenatal maternal blood pressure response to stress predicts birth weight and gestational age: A preliminary study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;175:706–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Giscombé CL, Lobel M. Explaining disproportionately high rates of adverse birth outcomes among African Americans: The impact of stress, racism, and related factors in pregnancy. Psychol Bull 2005;131:662–683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Glynn LM, Wadhwa PD, Dunkel-Schetter C, Chicz-DeMet A, Sandman CA. When stress happens matters: Effects of earthquake timing on stress responsivity in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001;184:637–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Suda T, Iwashita M, Ushiyama T, et al. Responses to corticotropin-releasing hormone and its bound and free forms in pregnant and nonpregnant women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1989;69:38–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Schulte H, Weisner D, Allolio B. The corticotrophin releasing hormone test in late pregnancy: Lack of adrenocorticotrophin and cortisol response. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf.) 1990;33:99–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Barron WM, Mujais SK, Zinaman M, Bravo EL, Lindheimer MD. Plasma catecholamine responses to physiologic stimuli in normal human pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1986;154:80–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Entringer S, Buss C, Shirtcliff EA, et al. Attenuation of maternal psychophysiological stress responses and the maternal cortisol awakening response over the course of human pregnancy. Stress 2009;13:258–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Matthews KA, Rodin J. Pregnancy alters blood pressure responses to psychological and physical challenge. Psychophysiology 1992;29:232–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Nisell H, Hjemdahl P, Linde B, Lunell N. Sympatho-adrenal and cardiovascular reactivity in pregnancy-induced hypertension. I. Responses to isometric exercise and a cold pressor test. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1985;92:722–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]