Abstract

Activation of striated muscle contraction occurs in response to Ca2+ binding to troponin C. The resulting reorganization of troponin repositions tropomyosin on actin and permits activation of myosin-catalyzed ATP hydrolysis. It now appears that the C-terminal 14 amino acids of cardiac troponin T (TnT) control the level of activity at both low and high Ca2+. We made a series of C-terminal truncation mutants of human cardiac troponin T, isoform 2, to determine if the same residues of TnT are involved in the low and high Ca2+ effects. We measured the effect of these mutations on the normalized ATPase activity at saturating Ca2+. Changes in acrylodan tropomyosin fluorescence and the degree of Ca2+ stimulation of the rate of binding of rigor myosin subfragment 1 to pyrene-labeled actin-tropomyosin-troponin were measured at low Ca2+. These measurements define the distribution of actin-tropomyosin-troponin among the three regulatory states. Residues SKTR and GRWK of TnT were required for the functioning of TnT at both low and high Ca2+. Thus, the effects on forming the inactive B-state and in retarding formation of the active M-state require the same regions of TnT. We also observed that the rate of binding of rigor subfragment 1 to pyrene-labeled regulated actin at saturating Ca2+ was higher for the truncation mutants than for wild-type TnT. This violated an assumption necessary for determining the B-state population by this kinetic method.

Introduction

Regulation of cardiac and skeletal muscle occurs through the actin-binding proteins troponin and tropomyosin. At low free Ca2+ concentrations, these proteins reduce the ability of actin to stimulate the rate of ATP hydrolysis by myosin or the active fragments: subfragment 1 (S1) and heavy meromyosin. That inhibition appears to occur because of a decrease in the kcat for ATP hydrolysis with a relatively small effect on the concentration of actin-tropomyosin-troponin required for half-maximal activation (1). The inhibition was not associated with a large weakening of binding of S1-ATP to actin in solution (1, 2, 3) or in rabbit psoas fibers (4, 5), although the cooperative binding of S1-ADP and rigor S1 to actin-tropomyosin-troponin is weakened at low free S1 concentrations (6). Inhibition of ATPase activity is thought to result from the presence of tropomyosin in a state that retards binding of myosin S1 to actin (7, 8, 9, 10, 11). That steric blocking of binding is likely restricted to “activating” forms of myosin such as rigor S1 or S1-ADP, as S1-ATP and analogs of S1-ATP bind differently (12, 13).

Three-dimensional reconstructions of electron micrographs of regulated actin filaments show different positions of tropomyosin on actin depending on the state of activation (10, 11). Differences in the states are seen depending on the sample preparation (11), but there appear to be at least three distinct states of tropomyosin. The B-state is inactive, and tropomyosin covers the site for rigor binding of myosin to actin. Tropomyosin is held in this inactive state through the concerted actions of troponin I (TnI), troponin T (TnT), and troponin C (TnC).

Binding of Ca2+ to TnC opens a hydrophobic cleft in TnC (14) to which the switch region of TnI can bind. The inhibitory region of TnI detaches from actin, allowing tropomyosin to explore two other configurations. The C-state (for calcium or closed) is the major state occupied at saturating Ca2+ and in the virtual absence of bound S1-ADP or rigor S1. That state, like the B-state, appears to be inactive (15). In the C-state, tropomyosin is bound to actin in an orientation where it partially covers the high-affinity myosin-binding site (10, 11). Evidence for this intermediate state came from several sources, including multiple step transitions associated with the binding of myosin to actin (16, 17, 18, 19) or the dissociation of myosin from actin (20, 21, 22). Although actin in this state does not activate myosin ATPase activity, the affinity for activating types of myosin (S1-ADP and rigor S1) is increased somewhat (6), as is the rate of binding of these same species (16, 17).

The other state that is populated at saturating Ca2+ is the open state or the M-state. In this state, tropomyosin is in a position in which it allows virtually unconstrained binding of rigor myosin (10, 11). In the open or M-state, actin is able to stimulate the ATPase activity of myosin (22, 23, 24). The three states of actin-tropomyosin-troponin are related by the following equilibrium constants: KB = [C]eq/[B]eq and KT = [M]eq/[C]eq (17). Differences remain in the interpretation of these states in terms of total activity (17, 25, 26, 27, 28), but there is agreement that the activity is proportional to the fraction of actin in the M-state.

Disease-causing mutations and other changes within the troponin complex alter the switching among these states (15, 29, 30, 31, 32). The Δ14 mutation of TnT appears to change both equilibrium constants, KB and KT. That mutant is one of two aberrant splice products resulting from a change in the splice donor sequence of intron 15 (33). Both the Δ14 and Δ28 + 7 troponin T mutations lead to an increase in activity (34, 35).

Actin filaments containing Δ14 TnT have an increased rate of binding to rigor S1 at low Ca2+ (22), loss of the change in acrylodan-labeled tropomyosin fluorescence associated with the formation of the B-state (20, 21, 22), and loss of the inhibition of S1 binding at low free S1 concentrations (29). Analyses of equilibrium-binding studies were consistent with the destabilization of the inactive state (lower values of L’) without a change in binding cooperativity (29). Incorporation of Δ14 TnT into both skeletal fibers and skinned trabeculae resulted in activation at lower Ca2+ concentrations (29). These observations led to the conclusion that formation of the inactive B-state is dependent on the last 14 residues of TnT.

The Δ14 TnT mutation also affected the behavior of actin filaments at saturating Ca2+. The changes observed included a doubling of the actin-activated ATPase activity at saturating Ca2+ (22). Furthermore, troponin containing both Δ14 TnT and A8V TnC fully activated actin filaments with Ca2+ even in the absence of activating cross-bridges. That is, the M-state can be reached even in the absence of high-affinity myosin binding. Indications of that possibility were shown earlier (36, 37). In wild-type actin filaments, the last 14 residues of TnT appear to limit the degree of activation by Ca2+. Neither the purpose of this limitation nor the mechanism of this limitation is understood.

Our goal is to identify key regions within the C-terminal 14 residues of human cardiac TnT that are responsible for forming the B-state and for limiting the M-state. The results show that the entire C-terminal region, containing six basic amino acid residues, is required for both effects. Residues SKTR and GRWK have a larger effect on activity than do the intermediary residues. We also show that S1 binds more rapidly to actin in the M-state than in the C-state. This observation affects calculations of the fraction of B-state from rates of binding of S1 to actin-tropomyosin-troponin.

Materials and Methods

Proteins

Isoform 2 of human cardiac TnT in pSBETa and human cardiac TnI in pET17b were expressed and purified as described earlier (29). Human cardiac TnC in pET3d was expressed (38) and reconstituted with TnI and TnT (39). The troponin subunits were dialyzed against 1 M NaCl, 1 M urea, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol, and 20 mM MOPS (pH 7). They were mixed in a 1:1:1.2 molar ratio and dialyzed three times for 8 hr each against the same buffer containing 6 M urea. The mixture was then dialyzed three times against the same buffer without urea. The salt concentration was reduced by successive dialyses against the same urea-free buffer containing 0.3 M NaCl and 0.1 M NaCl. The mixture was clarified by centrifugation and applied to a Mono Q 15HR column (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA) equilibrated in the same buffer. The troponin complex was eluted with an NaCl gradient to 0.6 M.

Tropomyosin was prepared from bovine cardiac left ventricles (40). Tropomyosin was labeled at cysteine 190 with acrylodan using a 10:1 molar ratio of acrylodan to tropomyosin (21). The extent of labeling (normally 70%) was determined using an extinction coefficient of 14,400 M−1 cm−1 at 372 nm (41). Actin was prepared from rabbit back muscle (42) and labeled with N-(1-pyrenyl) iodoacetamide (43). Myosin was also prepared from rabbit back muscle (44) and digested with chymotrypsin to produce the soluble S1 fragment containing the enzymatic activity (45). Animal use in this study was approved by the East Carolina University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Tropomyosin and troponin concentrations were determined by the Lowry assay with a bovine serum albumin standard. Other protein concentrations were determined from absorbance at 280 nm with correction for light scattering at a nonabsorbing wavelength. The extinction coefficients (ε0.1%) used for actin and S1 were 1.15 and 0.75, respectively. Molecular weights were assumed to be 42,000 (actin), 120,000 (myosin S1), 68,000 (tropomyosin), 24,000 (TnI), 35,923 (TnT), and 18,400 (TnC).

Estimation of the M-state by ATPase rate measurements

The initial time course of liberation of 32Pi from [γ-32P] ATP was measured with three to four time points to ensure linearity. Data were fitted to a straight line with Sigma Plot (Systat Software, San Jose, CA). Assays were run at 25°C with 0.1 μM S1, 10 μM F-actin, and 2.2 μM tropomyosin and troponin in a buffer containing 1 mM ATP, 3 mM MgCl2, 34 mM NaCl, 10 mM MOPS, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM EGTA, or 0.1 mM CaCl2 (pH 7.0). Rates were normalized to the minimal, νmin, and maximal, νmax, values obtained under identical conditions. The normalized rates, (νobs−νmin)/(νmax−νmin), were proportional to the fraction of actin in the M-state (22). ATPase rates were corrected for the rate of hydrolysis by S1 alone.

Relative B-state determination with acrylodan-labeled tropomyosin

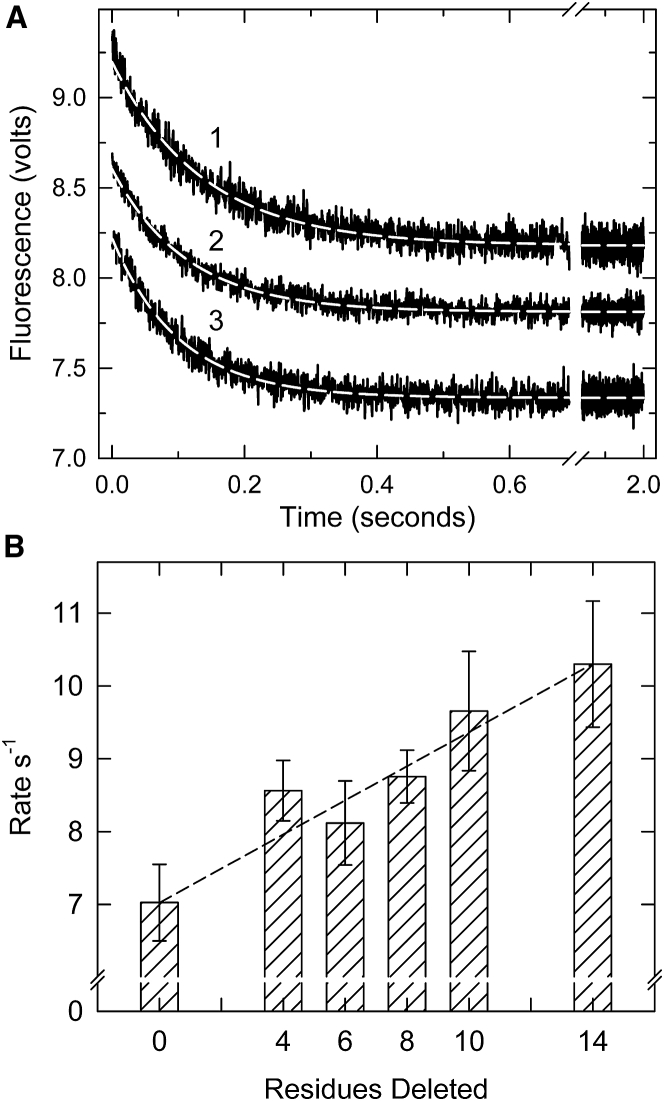

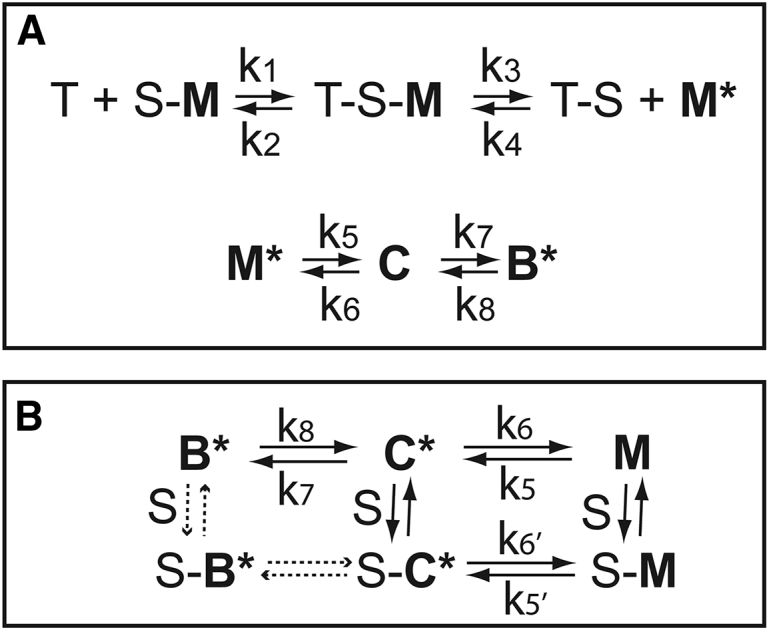

The fluorescence of acrylodan-labeled tropomyosin is sensitive to the state of tropomyosin on actin (20, 46). The amplitude of fluorescence is proportional to the fraction of actin regulatory units in the inactive B-state. The reaction is shown in Fig. 1 A.

Figure 1.

Reaction schemes describing measurements of the B-state both by acrylodan-tropomyosin fluorescence (A) and by pyrene-actin fluorescence (B). Actin filaments in the three states (M, C, and B) are shown in bold. T is ATP, and S is myosin S1. The presence of an asterisk denotes a high fluorescence state.

Actin filaments were stabilized in the M-state by attached rigor S1 (S) under conditions of low Ca2+. Upon rapid binding to ATP (T), S1 detached from M-state actin with an apparent rate constant of k3 + k4, allowing actin filaments to return to the inactive C- and B-states with apparent rate constants k5 + k6 and k7 + k8, respectively. At low Ca2+, the B-state predominates, and the amplitude of the signal is proportional to the occupancy of the B-state (20).

Actin with bound troponin, S1, and acrylodan-labeled tropomyosin was rapidly mixed with ATP at 10°C in a SF20 sequential mixing stopped-flow spectrometer (Applied Photophysics, Leatherhead, UK). The excitation monochrometer was set at 391 nm with a slit width of 0.5 mm. Fluorescence was measured through a long-pass filter with a cut-on midpoint of 451 nm and low and high transition points of 435 and 460 nm, respectively. The increase of the B-state was followed by an increase in acrylodan-tropomyosin fluorescence.

At saturating ATP, the rate of dissociation of S1 from actin was faster than the steps that followed. In most traces, the detachment of S1 and the transition from the M-state to the C-state were too fast to be observed. The transition from the C- to B-state has an observed rate of <10% of that for the M- to C-state transition. As a result, the observed transition to the B-state was monoexponential with an apparent rate constant equal to k7 + k8. Values of k7 + k8 were obtained by fitting a monoexponential function to the time courses. The values were identical to those obtained by fitting a set of ordinary differential equations describing Fig. 1 A to the data (20). The ratio of rate constants k8/k7 equals the ratio of state C to state B at equilibrium—that is, the equilibrium constant KB. Amplitudes were measured as the difference between the minimal and maximal fluorescence values of the monoexponential fits.

Estimation of B-state from kinetics of S1 binding to pyrene-labeled actin

The ratio of apparent rates of binding of S1 to actin-tropomyosin-troponin at saturating Ca2+ to low Ca2+ has been used to estimate the equilibrium constant defining the equilibrium ratio of state C to state B (17):

| (1) |

This equation requires that KT ≪ KB. The process is described in Fig. 1 B. As these measurements are normally made with rigor S1 or S1-ADP, it is assumed that the B-state does not bind to regulated actin. The dashed arrows indicate that significant binding of the B-state may only occur during steady-state ATP hydrolysis and not during the rigor condition used here. The values of the rate constants k5′and k6′ are only equal to k5 and k6 if the myosin S1 (S) bound equally well to actin in the C- and M-states. That assumption may be incorrect (see Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Binding of S1 to excess pyrene-labeled actin filaments containing tropomyosin and troponin in the absence of ATP at saturating Ca2+. (A) Averages of ≥5 time courses of binding to actin filaments containing troponin with wild-type troponin T, curve 1; Δ8 troponin T, curve 2; and Δ14 troponin T, curve 3. Dashed lines are single exponential fits of the data. (B) The observed rate of binding of S1 to actin-tropomyosin containing troponin with different mutants of troponin T is shown. Error bars shown are the SDs. Conditions are as follows: the same as those in Fig. 5, except that 0.2 mM Ca2+ was substituted for the EGTA. The dashed line shows the expected behavior if each residue contributed equally to the effect measured.

The rate of binding of S1 to pyrene-labeled actin-tropomyosin-troponin was measured in the stopped flow with excitation at 365 nm with 0.5 or 1 mm slit widths and emission measured through a long-pass filter with a midpoint of 400 nm. Pyrene-labeled actin was stabilized with a 1:1 complex of phalloidin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The phalloidin-stabilized pyrene-labeled actin-tropomyosin-troponin complex was rapidly mixed with nucleotide-free myosin S1 in the stopped flow. Rates were measured at very low Ca2+ (2 mM EGTA) or at 0.5 mM Ca2+. Student’s t-tests were performed with SigmaPlot (Systat Software) or SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Results

Replacement of wild-type human cardiac TnT with the Δ14 mutant reduced or eliminated the B-state at low Ca2+ and enhanced the M-state at saturating Ca2+ (22). We sought to identify areas within the C-terminal region that are critical for these Ca2+-dependent effects on the distribution of actin states. We were particularly interested in determining if the same residues were required for both activities. Our approach was to measure changes in the M- and B-states with a series of deletion mutants of TnT.

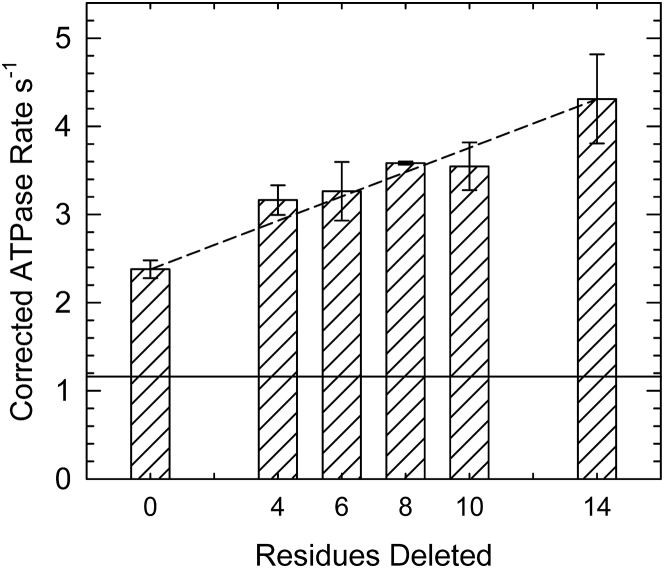

The effects of C-terminal TnT residues on the formation of the active M-state at saturating Ca2+ were determined by ATPase activities. At the concentration of actin used, the rates are proportional to the ratio of Vmax/Kapp, where Kapp is [actin] at 50% Vmax (22). Fig. 2 shows that cardiac wild-type troponin-tropomyosin increased the actin-stimulated rate of ATP hydrolysis by ∼2-fold at saturating Ca2+. Full activation does not normally occur in the absence of binding of “activating” forms of myosin such as rigor S1, S1-ADP, or N-ethylmaleimide-modified S1. Fig. 2 shows that substitution of Δ4, Δ6, Δ8, Δ10, and Δ14 TnT for the wild-type increased ATPase activity in proportion to the deletion size.

Figure 2.

For a Figure360 author presentation of Fig. 2, see the figure legend at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2018.06.028#mmc1.

ATPase rates of myosin S1 in the presence of actin and actin-tropomyosin containing troponin with different mutants of troponin T at saturating Ca2+. Measurements were made at 25°C and pH 7.0 in solutions containing 1 mM ATP, 3 mM MgCl2, 34 mM NaCl, 10 mM MOPS, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.1 mM CaCl2. The concentrations of S1, actin, tropomyosin, and troponin were 0.1, 10, 2.2, and 2.2 μM, respectively. The average rate for wild-type-regulated actin over all experiments was 2.4/s (±0.1). Corrected rate = average of all wild-type experiments∗ (measured mutant rate/measured wild-type rate). Error bars are the SDs. The solid line shows the rate observed in the absence of troponin and tropomyosin. The dashed line shows the expected behavior if each residue contributed equally to the effect measured.

Slightly greater changes occurred between wild-type and Δ4 and between Δ10 and Δ14 (compare with dotted line), so these data could also be described by a step function. Actin filaments containing Δ14 TnT had 1.8 times the rate of actin containing wild-type troponin and 3.7 times the rate of unregulated actin (22). Although the Δ14 deletion had the maximal value of Vmax/Kapp for this series, it is ∼62% of the highest possible value (22).

Because only the M-state of actin filaments stimulates myosin ATPase activity (15), the previous results can be shown in terms of the fraction of M-state that is formed. This is done by comparing the ATPase rates with the minimal rates and maximal possible rates at identical conditions. The minimal rate that we have observed is 0.61× the rate observed with wild-type troponin at very low Ca2+ (31). The maximal rate was formerly determined with N-ethylmaleimide-labeled S1 (29) or with actin filaments containing both A8V TnC and Δ14 TnT. That construct had an ATPase rate 6.5 times that of unregulated actin (22). Table 1 shows the population of actin in the active M-state for each troponin mutant. These values are likely to be dependent on conditions such as the ionic strength and the concentration of ATP.

Table 1.

Fraction of Actin in the M-State for Actin Filaments at Saturating Ca2+ and Containing Various Mutants of TnT

| TnT Mutant | FMa |

|---|---|

| Wild-type | 0.34 |

| Δ4 | 0.45 |

| Δ6 | 0.46 |

| Δ8 | 0.50 |

| Δ10 | 0.50 |

| Δ14 | 0.62 |

M-state = (ATPase rate)/(6.5 × unregulated actin ATPase rate).

The second question is whether the regions of TnT required for forming the B-state are the same as those observed in Fig. 2 for destabilizing the M-state. This was first examined with acrylodan-labeled tropomyosin, which reports transitions from states M to C to B at low Ca2+ (20). Fig. 3 shows the time course of acrylodan tropomyosin fluorescence when S1-actin-tropomyosin-troponin was rapidly mixed with ATP. Because there was no appreciable S1 bound to actin during these reactions, the distributions observed are for free regulated actin filaments.

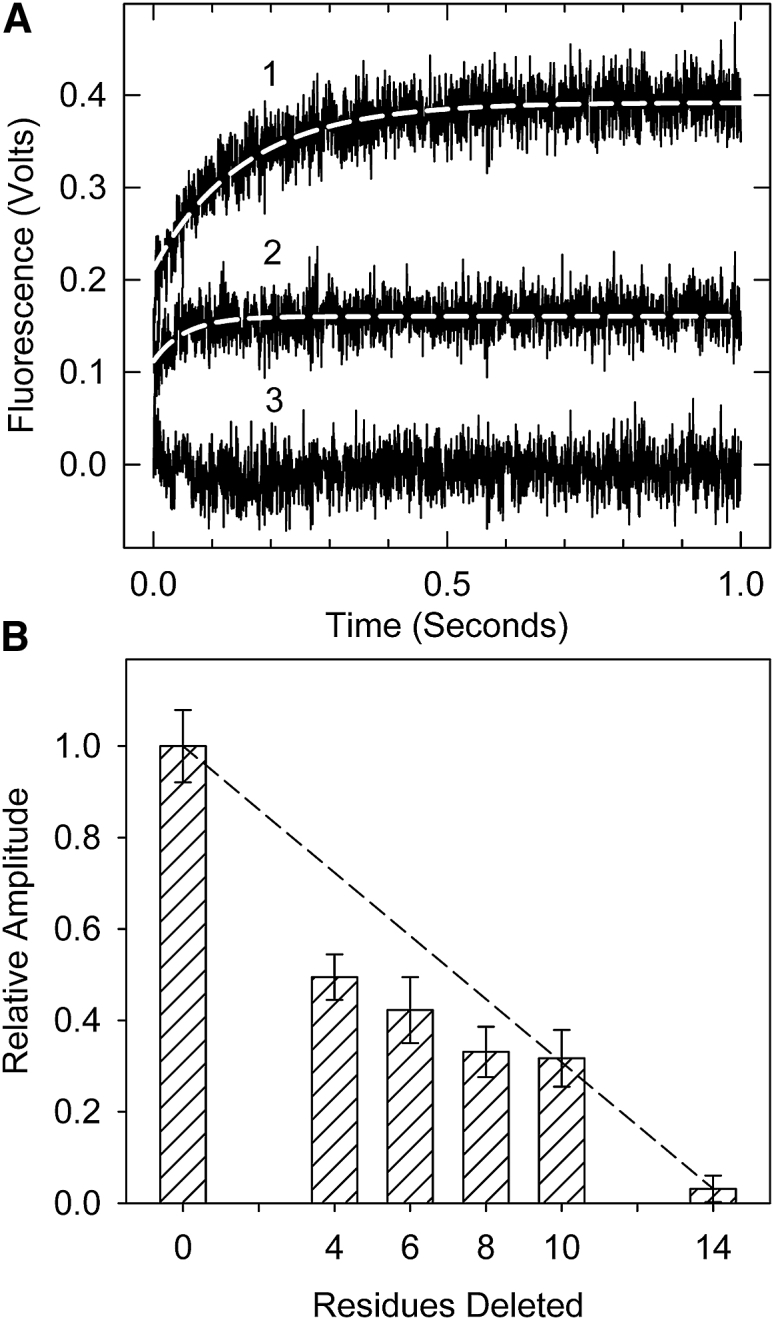

Figure 3.

Formation of the inactive B-state seen by acrylodan-tropomyosin fluorescence. (A) Time courses of acrylodan fluorescence changes are shown after the rapid detachment of myosin S1 in the absence of Ca2+ at 10°C. Traces shown are averages of at least three different measurements. (B) Relative fluorescence amplitude for actin filaments containing wild-type and truncated troponin T is shown. The associated apparent rate constants were 6.8, 6.9, 6.5, 7.4, and 6.1 per s for the wild-type through Δ10 mutants, respectively. No rate constant could be determined for Δ14. Conditions are as follows: 2 μM actin, 0.86 μM tropomyosin, 1.4 μM troponin, and 2 μM S1 in 20 mM MOPS, 152 mM KCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 2 mM EGTA were rapidly mixed with 2 mM ATP, 20 mM MOPS, 152 mM KCl, 8 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 2 mM EGTA. The dashed line shows the expected behavior if each residue contributed equally to the effect measured.

The decrease in fluorescence in transitioning from the M-state to the C-state (20) was too fast to observe in this study. Shown in Fig. 3 are the monoexponential increases in fluorescence reflecting the slower transition from the C- to the B-state. Curve 1 is actin-tropomyosin with wild-type troponin. The amplitude of the fluorescence increase (0.17 V) is proportional to the amount of actin in the B-state. Curve 3 shows a time course for the transition with actin regulated by troponin containing Δ14 TnT. The amplitude of the fluorescence increase in this case was near zero, confirming the absence of the B-state. Curve 2 is actin-tropomyosin-troponin containing the Δ10 TnT troponin truncation mutant. The Δ10 mutant had an amplitude of 0.7 V, intermediate to that of actin-tropomyosin containing wild-type and Δ14 TnT troponin. This reduced amplitude reflects a partial loss of the B-state relative to the wild-type.

The change in fluorescence amplitude (B-state occupancy) with decreasing length of the C-terminal region of TnT is shown in Fig. 3 B. Each truncation mutant had a statistically lower fluorescence amplitude than that of the wild-type regulated actin. The largest decreases in state B occupancy occurred between wild-type and Δ4 with another substantial change between Δ10 and Δ14. This pattern was similar to that seen for the B-state in Fig. 2. The apparent rate constant for the transition from the C-state to the B-state (k7 + k8) did not change from wild-type to Δ10. It was impossible to obtain a rate measurement for the Δ14 case.

Another way to distinguish among the states is to take advantage of their different rates of binding to myosin S1 (16, 17). In the absence of ATP, myosin S1 binds to actin-tropomyosin-troponin at a higher rate in saturating Ca2+ than in virtually Ca2+ free solution. This difference in binding occurs with either excess S1 or excess actin at pseudo first-order conditions. Unlike the acrylodan-tropomyosin assay, this reports the transition of actin filaments with either some (excess actin) or total (excess S1) saturation with S1.

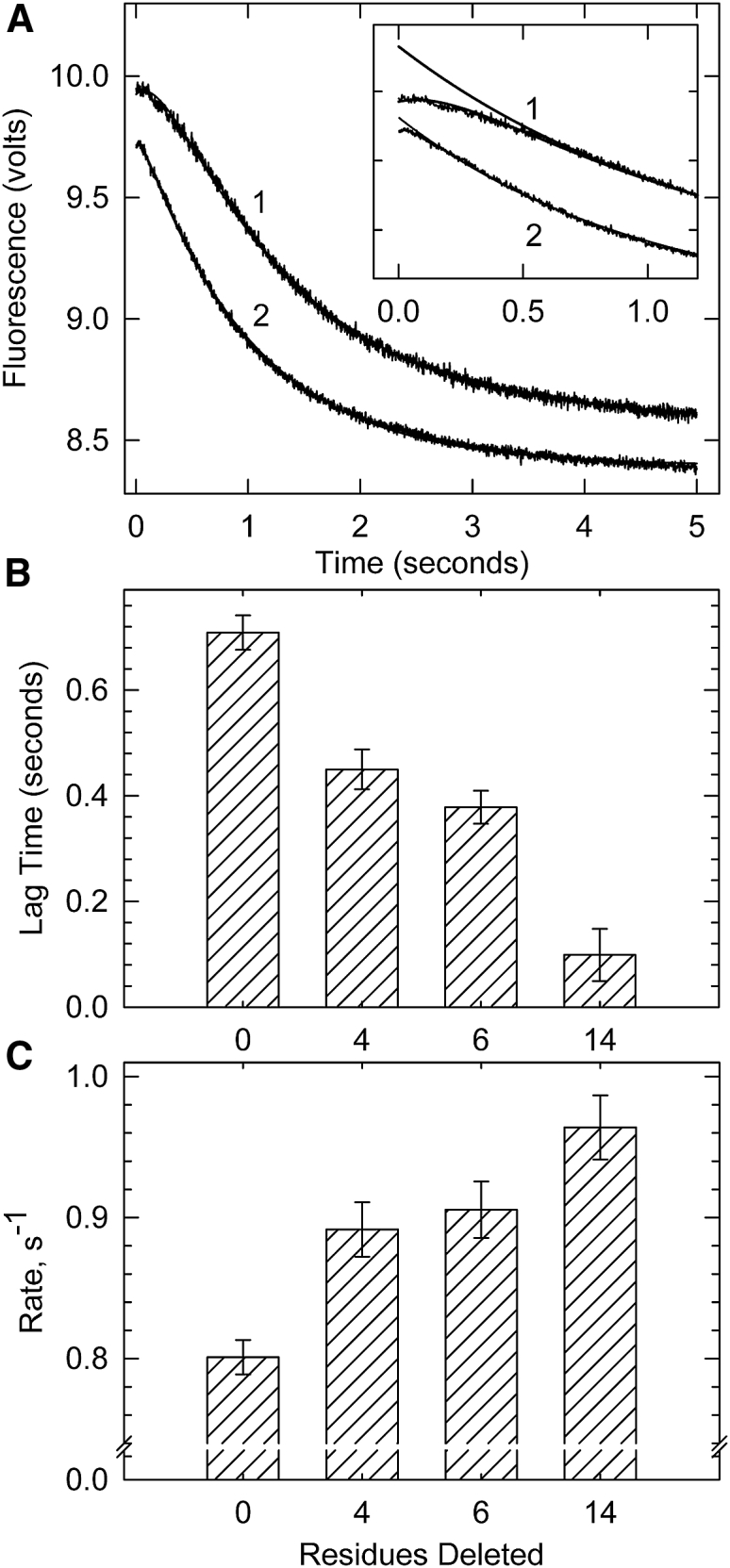

Fig. 4 shows time courses for the binding of excess S1 to actin-tropomyosin-troponin at a very low Ca2+ concentration. These curves are complex because increases in the amount of S1 bound during the reaction increase both the population of the M-state and the rate of binding. The presence of the B-state is seen by an initial lag and a reduction in the subsequent exponential phase of binding (17, 47). This lag is thought to represent an initial blocked state population of actin filaments that do not bind to myosin (17, 48) or that bind slowly (13, 47). Binding to actin filaments containing wild-type TnT, curve 1, has a lag indicative of a high population of the B-state. This initial lag was largely eliminated when wild-type TnT was replaced with the Δ14 mutant (curve 2), showing that the last 14 residues of TnT are required to form the B-state.

Figure 4.

Binding of excess S1 to pyrene-labeled actin filaments containing tropomyosin and troponin in the absence of ATP at very low Ca2+. (A) Averages of ≥5 time courses of S1 binding to actin filaments containing troponin with wild-type troponin T, curve 1, or Δ14 troponin T, curve 2 are shown. Exponential fits are superimposed on the curves. Inset: expanded view of initial 0.2 s shown with the major rapid exponential phase extrapolated back to illustrate the lag. (B) Lag time preceding the exponential phase against troponin type is shown. (C) Apparent rate constants for the major rapid exponential phase of binding against troponin variant are shown. Error bars shown are the SDs. Conditions are as follows: at 25°C, 0.2 μM pyrene-actin (40% labeled), 0.086 μM tropomyosin, and 0.086 μM troponin were rapidly mixed with 2 μM myosin S1 in a buffer containing 152 mM KCl, 20 mM MOPS buffer (pH 7), 4 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 2 mM EGTA.

A histogram showing the effects of shortening the C-terminal region of TnT on the lag duration is shown in Fig. 4 B. The duration of the lag was obtained by fitting a multiexponential function to the traces. The time between the start of the reaction and the beginning of the rapid exponential change was the lag time. TnT lacking the terminal 4, 6, or 14 residues had statistically lower lags than those of the wild-type regulated actin, indicating decreases in the B-state population. The extent of the lag decreased, and the rate of S1 binding increased as the C-terminal region of TnT was shortened. Fig. 4 C shows changes in the rate of the first and major phase of the double exponential fit to the data after the lag phase (the slow second phase did not vary among the mutants). Troponin mutants containing Δ4, Δ6, or Δ14 TnT each had a statistically higher rate of binding than that of wild-type regulated actin, indicating a decrease in the B-state of actin. Δ14 TnT produced the highest rate of pyrene fluorescence change corresponding to the lowest initial B-state population of the troponin mutants measured. Both approaches to examine the B-state (Figs. 2 and 3) showed a progressive loss of the B-state as the C-terminal region was truncated. They also showed a large change between wild-type and Δ4 TnT containing actin filaments.

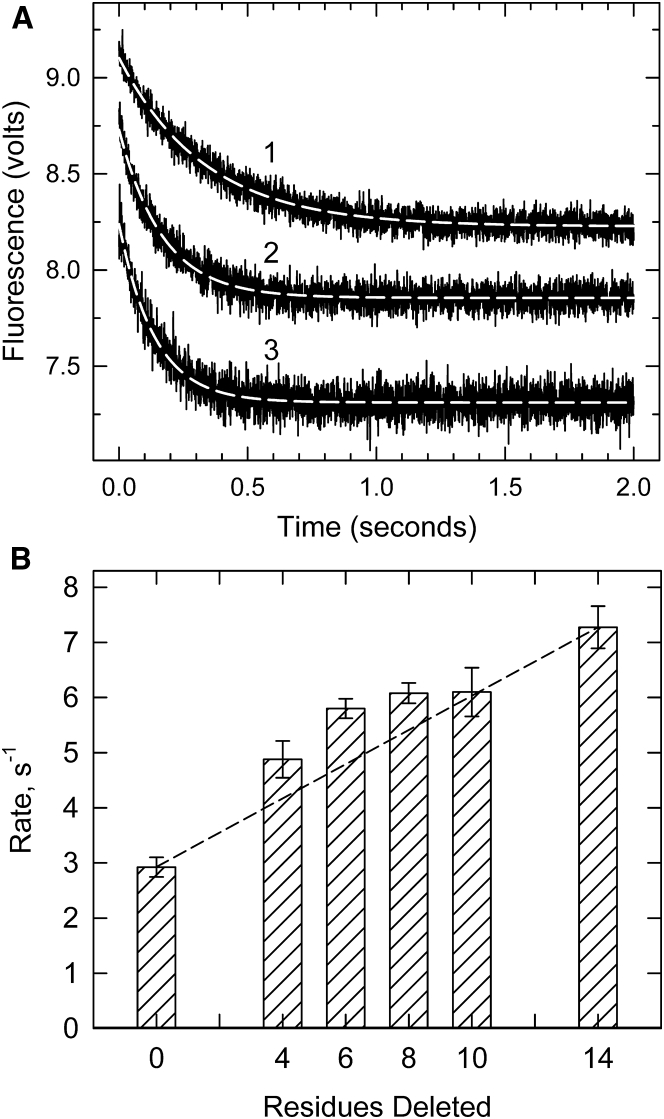

Measurements of the kinetics of S1 binding to pyrene-labeled actin are simpler when actin-tropomyosin-troponin is in large excess over S1. At that condition, there is little stabilization of the C- and M-states due to S1 binding. Fig. 5 A shows examples of binding isotherms at a very low Ca2+ concentration. The rates of binding increased in going from actin filaments containing wild-type troponin (curve 1) to those containing either Δ6 TnT (curve 2) or Δ14 TnT (curve 3). Deletions from the C-terminal region of TnT led to an increased rate of binding, indicating a lower initial B-state population.

Figure 5.

Rate of binding of S1 to an excess of pyrene-labeled actin filaments containing tropomyosin and troponin in the absence of ATP at a very low Ca2+ concentration. (A) Averaged time courses of binding to actin-tropomyosin containing wild-type troponin T (curve 1), Δ6 troponin T (curve 2), and Δ14 troponin T (curve 3). Dashed lines are single exponential fits. (B) The observed rate of binding of S1 to actin-tropomyosin containing troponin with different mutants of troponin T is shown. Error bars shown are the SDs for at least five experiments. Conditions are as follows: the same as those in Fig. 4, except that 4 μM pyrene-actin (40% labeled), 0.86 μM tropomyosin, and 1.7 μM troponin were rapidly mixed with 0.4 μM myosin S1. The dashed line shows the expected behavior if each residue contributed equally to the effect measured.

The profile of changes in rate with the extent of truncation of TnT is shown in Fig. 5 B. Each truncation mutant showed a statistically higher rate of fluorescence change than that of wild-type troponin regulated actin. Deletion of the last four residues (GRWK) from TnT produced a large (70%) increase in the rate of binding, as had been seen for other assays of the B-state in Figs. 2 and 3. Additional increases were observed for subsequent deletions Δ6, Δ8, and Δ10.

The rate of binding of S1 to pyrene-labeled actin is thought to be at its maximal value at saturating Ca2+. That value is required for estimation of the B-state by Eq. 1. Isotherms for binding S1 to an excess of actin filaments at saturating Ca2+ with wild-type Δ8 and Δ14 TnT are shown in Fig. 6 A. Each curve is shown with a monoexponential fit to the data. The rate of binding to wild-type filaments was 7/s. That value is 2.3× the wild-type rate at low Ca2+ and is equal to the value observed for actin filaments containing Δ14 TnT at low Ca2+.

The apparent rate of binding of S1 to actin filaments at saturating Ca2+ increased as the C-terminal region of TnT was shortened. Fig. 6 B shows that rates of binding in Ca2+ increased in a near linear fashion as residues were deleted from the C-terminal region of TnT. The maximal observed rate occurred with Δ14 TnT containing filaments in which the apparent rate constant was ∼1.4× the rate measured with wild-type troponin. Again, there was a particularly large increase in rate between wild-type and Δ4 TnT, as seen in all previous cases.

Discussion

The C-terminal region of TnT is essential for forming the inactive B-state of actin-tropomyosin-troponin (21, 29). Furthermore, that region limits the extent of activation by Ca2+ (29). Stepwise shortening of the C-terminal region of TnT caused progressive loss of the B-state at low Ca2+ and gain of the M-state at saturating Ca2+. The importance of TnT residues for forming both the B- and M-states followed this order: GRWK288 > SKTR278 > GKAKVT284. It is notable that the loss of B-state did not result in a commensurate increase in the M-state as observed by ATPase activities at low Ca2+ (22). That is further evidence for an intermediate inactive state in the regulatory mechanism.

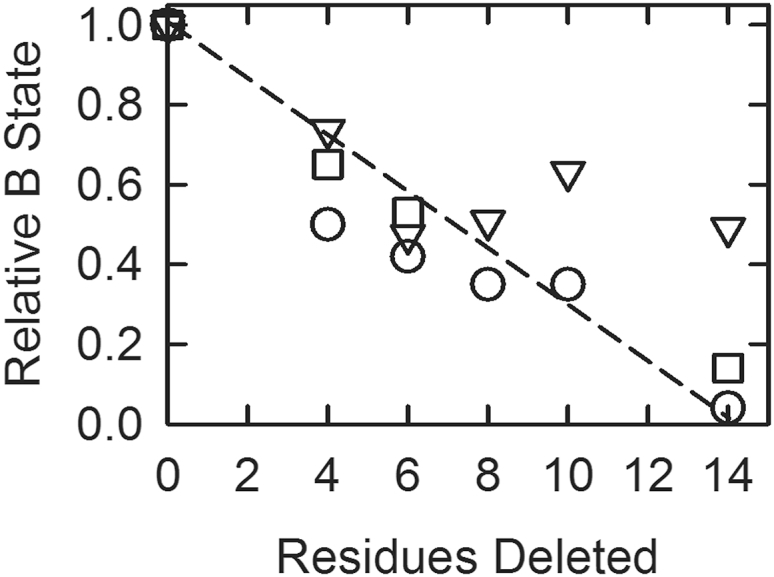

Although all studies showed a loss of the B-state as the C-terminal region was shortened, calculations using Eq. 1 deviated from the other measurements. The results are compared in Fig. 7. For the purposes of comparison, all data are shown as the fraction of the B-state relative to that seen with wild-type actin filaments. Estimates from Eq. 1 (triangles) deviated from acrylodan-tropomyosin measurements (circles) and lag durations (squares) for the mutant’s Δ10 through Δ14.

Figure 7.

The fraction of actin filaments in the B-state relative to wild-type values at low Ca2+ for different troponin T deletion mutants. Values were calculated from acrylodan tropomyosin fluorescence amplitudes (circles), the duration of the lag in binding of excess S1 to actin (squares), and from Eq. 1 (triangles). The latter were calculated using a different rate of binding in Ca2+ for each deletion mutant. The dashed line shows the expected behavior if each residue contributed equally to the effect measured.

Acrylodan tropomyosin fluorescence amplitudes (Fig. 3) give levels of the B-state relative to the wild-type levels (20, 22) in the absence of bound activating myosin. The duration of the lag in binding of excess S1 to regulated filaments (Fig. 4) also gives a relative measure of the B-state. Determination of the absolute level of B-state by these methods requires a standard. At present, no independent standard exists. Differences in distribution are readily measured by these methods, and this is the primary goal of this study.

Equation 1 is an attempt to measure the absolute levels of the B-state from the rates of binding of S1 to actin compared to rates at saturating Ca2+ (17). The assumptions implicit in this method are as follows: 1) the reduction in binding rates at low Ca2+ results from steric blocking of a fraction of potential binding sites on actin, 2) no appreciable B-state exists at saturating Ca2+, and 3) S1 binding kinetics is the same for actin filaments in the C- and M-states. The first assumption is not universally accepted (13, 47, 49). The second and third assumptions provide the necessary benchmarks. The third assumption was tested here and found to be invalid (Fig. 6). The rate of binding to the M-state was ∼13/s compared with 6/s for the C-state and 3/s for the B-state. We suggest that the deviation of Eq. 1 from the other measurements results from the limitations of the assumptions on which it is based. That is, the rate of binding at saturating Ca2+ is not an appropriate standard, at least in the case under investigation here.

Formation of the B-state at low Ca2+ is thought to occur because the inhibitory region (residues 137–148) and mobile domain (residues 163–210) of TnI bind to actin when the regulatory Ca2+ site of TnC is empty. It appears now that forming the B-state also requires the C-terminal region of TnT. How this functions is unclear. The C-terminal region of TnT is highly basic and natively unstructured and thus invisible to x-ray and NMR analyses. Deuterium/hydrogen exchange studies showed that in the isolated troponin complex, the C-terminal region of TnT exhibits rapid exchange. Ca2+ decreases the exchange rate of TnT at the C-terminal region of the IT helix (the coiled coil formed between TnI and TnT) adjacent to the C-terminal 14 residues (50). Thus, there appear to be Ca2+-dependent changes near the C-terminal region of TnT. The region adjacent to the C-terminus of skeletal TnT binds to TnC (51), but the interactions of the last 14 residues are unknown.

The C-terminal region of TnT also retards the formation of the M-state at saturating Ca2+. The last four residues may have a slightly greater impact on the M-state than the remainder of the C-terminal 14 residues, but all residues appeared to participate in that function. At a low actin concentration, the S1 ATPase rate for actin filaments fully in the M-state was 6.5 times the rate seen with S1 and pure actin (no tropomyosin or troponin) (22). The presence of troponin and tropomyosin significantly enhances actin activation at saturating Ca2+ (23, 29, 36, 37, 52, 53, 54). That activation beyond actin alone is most often seen with the accumulation of high-affinity myosin species (rigor S1 or S1-ADP) and has been attributed to S1 forcing tropomyosin to move away from the high-affinity binding sites on actin for myosin. However, troponin itself appears to modulate the position of tropomyosin on actin at saturating Ca2+ as well as low Ca2+. Human cardiac troponin lacking the C-terminal region of TnT gave close to 70% of full activation (i.e., 70% M-state stabilization) with Ca2+ alone, and the combination of A8V TnC and Δ14 TnT led to full activation with Ca2+ (22). It may be that the large activation of ATPase activity as rigor S1 accumulates is observed only because the C-terminal region of TnT limits the movement of tropomyosin into the activating position.

The effects of the C-terminal 14 residues of TnT on the B- and M-states did not appear to be due to a few key residues. Rather, both activities depended on a long patch of basic residues. The importance of basic amino acid residues in the C-terminal region of TnT is reinforced by other observations. Two mutations at R278 (55, 56, 57) and two at R286 (58) result in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The R278C mutation leads to somewhat increased ATPase activity at both low and saturating Ca2+ (55) and to an increase in Ca2+ sensitivity for force development (55, 59). That is qualitatively similar to the pattern reported here. The R278C mutation of TnT is also able to partially rescue the effects of the R145G TnI mutation at saturating Ca2+ (60). The R278P mutation alters the dynamics of the unstructured C-terminal region of TnT (57).

Just outside the Δ14 region is another disease-causing mutation of a basic residue associated with hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy. K273E TnT increased Ca2+ sensitivity in the in vitro motility assay (61, 62) and eliminated the normal response to TnI phosphorylation (62) but did not significantly affect actomyosin ATPase activity (61).

Like the Δ14 mutation, deletion of the 28 C-terminal residues and addition of seven residues (Δ28 + 7 TnT) leads to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a loss of cooperative binding of S1, and an elevated ATPase activity at low Ca2+ (34). Both the Δ28 + 7 and the Δ14 mutants lowered cooperativity and increased the sensitivity of force to Ca2+ (35). Myocytes from transgenic mice having this mutation were also hypercontractile (63). Yet, the position of tropomyosin at saturating and low Ca2+ appeared like wild-type filaments (34). The affinity of troponin containing Δ28 + 7 TnT for actin-tropomyosin was decreased especially at low Ca2+ where the affinity was 22% of wild-type. The authors of that study proposed that the TnT deletion lowered the energy barrier among the states of actin so that transitions could occur more readily. In the case of Δ14 TnT, the equilibrium constant between the B- and C-states changed, but there was no change in the apparent rate constant, k7 + k8, for the transition from the C-state to the B-state. It is possible that the decrease in the ratio of [B]/[C] was due to both increases in k7 and decreases in k8. However, uncertainty remains because useful kinetic data could only be obtained over a limited range of [B]/[C] because of diminishing signals.

The involvement of both TnT and TnI in forming the B-state is reasonable, as there is evidence of an evolutionary and functional relationship between these subunits (60, 64). Both the C-terminal domain of TnT and the inhibitory domain of TnI (residues 137–148) emerge from the IT helix (the coiled coil formed between TnI and TnT), which includes residues 226–271 of human cardiac TnT (65). The inhibitory domain of TnI is highly basic, like the C-terminal region of TnT, and at 11 residues is only slightly smaller. The spatial and sequence similarity of the C-terminal region of TnT to the TnI inhibitory domain raises the possibility that the C-terminus of TnT may bind to actin and affect tropomyosin placement.

The N-terminal hypervariable region of TnT also modulates contraction (66, 67). Alternative splicing at the N-terminus leads to isoforms with varied charge; those with a greater negative charge have a higher relative force in skinned fibers at low Ca2+ and are activated at lower Ca2+ concentrations (68). A higher Ca2+ sensitivity was also associated with the negatively charged N-terminus of TnT in chicken skeletal muscle (69). Deletion of the N-terminal region of TnT leads to a decrease in ATPase activity to 70% of wild-type at low Ca2+ and 83% of wild-type at saturating Ca2+ and a higher affinity for tropomyosin (70). The effects of N-terminal loss are milder than those of C-terminal loss, and the loss of charge produces decreased activity rather than increased activity, as seen with C-terminal TnT truncation. Although these regions have opposite charges, they do not appear to have a shared function.

The effects of C-terminal 14 residues of cardiac TnT are likely the result of binding to other thin filament proteins. The C-terminal region of TnT may bind to TnC (65), the N-terminal of TnT (71), actin (72, 73, 74) or near cys 190 of tropomyosin (75, 76, 77, 78). The binding of TnT to tropomyosin was localized to the TnT2 region, which is the C-terminal 40% of the molecule). The last 17 residues of TnT contribute to tropomyosin binding (76), although another study placed the tropomyosin binding site near the N-terminal part of the TnT2 (79). Although these results are intriguing, this story is incomplete.

The presence of an element within TnT that modulates the degree of actin activation at both low and saturating Ca2+ opens the possibility that the interactions of the C-terminal region of TnT are regulated. It is conceivable that posttranslational modification of the C-terminal region of TnT or its binding target alters the Ca2+ response. Phosphorylation sites of troponin (80, 81) and tropomyosin (82) are known. The C-terminal TnT residues S275 and T284 are targets for protein kinase C and the ROCKII pathway (83). The effects of phosphorylation of T284 have been studied, but only in combination with phosphorylation at other sites (84, 85).

Conclusions

Residues SKTR and GRWK of TnT are particularly important for forming the B-state at low Ca2+ and for limiting the M-state at saturating Ca2+. In the absence of the C-terminal TnT residues, troponin appears to be able to stabilize tropomyosin in the active M-state without much assistance from S1-ADP or rigor S1 binding to actin. This self-limitation raises the possibility that the interactions of this region are regulated. Furthermore, the C-terminal region of TnT may be part of a myosin-activated regulatory switch (13).

Author Contributions

D.J. performed the research, analyzed the data, and contributed to the writing of the article. C.W.A. designed and produced the troponin mutants. J.M.C. designed the research, analyzed the data, and contributed to the writing of the article.

Editor: David Warshaw.

References

- 1.Chalovich J.M., Eisenberg E. Inhibition of actomyosin ATPase activity by troponin-tropomyosin without blocking the binding of myosin to actin. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:2432–2437. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalovich J.M., Chock P.B., Eisenberg E. Mechanism of action of troponin. tropomyosin. Inhibition of actomyosin ATPase activity without inhibition of myosin binding to actin. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:575–578. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.el-Saleh S.C., Potter J.D. Calcium-insensitive binding of heavy meromyosin to regulated actin at physiological ionic strength. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:14775–14779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kraft T., Chalovich J.M., Brenner B. Parallel inhibition of active force and relaxed fiber stiffness by caldesmon fragments at physiological ionic strength and temperature conditions: additional evidence that weak cross-bridge binding to actin is an essential intermediate for force generation. Biophys. J. 1995;68:2404–2418. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80423-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenner B., Schoenberg M., Eisenberg E. Evidence for cross-bridge attachment in relaxed muscle at low ionic strength. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1982;79:7288–7291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.23.7288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greene L.E., Eisenberg E. Cooperative binding of myosin subfragment-1 to the actin-troponin-tropomyosin complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1980;77:2616–2620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.2616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huxley H.E., Simmons R.M., Koch M.H. Millisecond time-resolved changes in x-ray reflections from contracting muscle during rapid mechanical transients, recorded using synchrotron radiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;78:2297–2301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.4.2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spudich J.A., Huxley H.E., Finch J.T. Regulation of skeletal muscle contraction. II. Structural studies of the interaction of the tropomyosin-troponin complex with actin. J. Mol. Biol. 1972;72:619–632. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(72)90180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parry D.A., Squire J.M. Structural role of tropomyosin in muscle regulation: analysis of the x-ray diffraction patterns from relaxed and contracting muscles. J. Mol. Biol. 1973;75:33–55. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90527-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pirani A., Xu C., Lehman W. Single particle analysis of relaxed and activated muscle thin filaments. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;346:761–772. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Risi C., Eisner J., Galkin V.E. Ca2+-induced movement of tropomyosin on native cardiac thin filaments revealed by cryoelectron microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:6782–6787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1700868114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chalovich J.M., Greene L.E., Eisenberg E. Crosslinked myosin subfragment 1: a stable analogue of the subfragment-1.ATP complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1983;80:4909–4913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.16.4909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Resetar A.M., Stephens J.M., Chalovich J.M. Troponin-tropomyosin: an allosteric switch or a steric blocker? Biophys. J. 2002;83:1039–1049. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75229-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herzberg O., Moult J., James M.N. A model for the Ca2+-induced conformational transition of troponin C. A trigger for muscle contraction. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:2638–2644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mathur M.C., Kobayashi T., Chalovich J.M. Some cardiomyopathy-causing troponin I mutations stabilize a functional intermediate actin state. Biophys. J. 2009;96:2237–2244. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.12.3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trybus K.M., Taylor E.W. Kinetic studies of the cooperative binding of subfragment 1 to regulated actin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1980;77:7209–7213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKillop D.F., Geeves M.A. Regulation of the interaction between actin and myosin subfragment 1: evidence for three states of the thin filament. Biophys. J. 1993;65:693–701. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81110-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miki M., Kobayashi T., Maéda Y. Ca2+-induced distance change between points on actin and troponin in skeletal muscle thin filaments estimated by fluorescence energy transfer spectroscopy. J. Biochem. 1998;123:324–331. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimura C., Maeda K., Miki M. Ca(2+)- and S1-induced movement of troponin T on reconstituted skeletal muscle thin filaments observed by fluorescence energy transfer spectroscopy. J. Biochem. 2002;132:93–102. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a003204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borrego-Diaz E., Chalovich J.M. Kinetics of regulated actin transitions measured by probes on tropomyosin. Biophys. J. 2010;98:2601–2609. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franklin A.J., Baxley T., Chalovich J.M. The C-terminus of troponin T is essential for maintaining the inactive state of regulated actin. Biophys. J. 2012;102:2536–2544. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baxley T., Johnson D., Chalovich J.M. Troponin C mutations partially stabilize the active state of regulated actin and fully stabilize the active state when paired with Δ14 TnT. Biochemistry. 2017;56:2928–2937. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b01092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bremel R.D., Murray J.M., Weber A. Manifestations of cooperative behavior in the regulated actin filament during actin-activated ATP hydrolysis in the presence of calcium. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1972;37:267–275. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams D.L., Jr., Greene L.E., Eisenberg E. Cooperative turning on of myosin subfragment 1 adenosinetriphosphatase activity by the troponin-tropomyosin-actin complex. Biochemistry. 1988;27:6987–6993. doi: 10.1021/bi00418a048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hill T.L., Eisenberg E., Greene L. Theoretical model for the cooperative equilibrium binding of myosin subfragment 1 to the actin-troponin-tropomyosin complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1980;77:3186–3190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.6.3186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hill T.L., Eisenberg E., Chalovich J.M. Theoretical models for cooperative steady-state ATPase activity of myosin subfragment-1 on regulated actin. Biophys. J. 1981;35:99–112. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(81)84777-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith D.A., Geeves M.A. Cooperative regulation of myosin-actin interactions by a continuous flexible chain II: actin-tropomyosin-troponin and regulation by calcium. Biophys. J. 2003;84:3168–3180. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)70041-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mijailovich S.M., Li X., Geeves M.A. Resolution and uniqueness of estimated parameters of a model of thin filament regulation in solution. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2010;34:19–33. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gafurov B., Fredricksen S., Chalovich J.M. The delta 14 mutation of human cardiac troponin T enhances ATPase activity and alters the cooperative binding of S1-ADP to regulated actin. Biochemistry. 2004;43:15276–15285. doi: 10.1021/bi048646h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathur M.C., Chase P.B., Chalovich J.M. Several cardiomyopathy causing mutations on tropomyosin either destabilize the active state of actomyosin or alter the binding properties of tropomyosin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011;406:74–78. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.01.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mathur M.C., Kobayashi T., Chalovich J.M. Negative charges at protein kinase C sites of troponin I stabilize the inactive state of actin. Biophys. J. 2008;94:542–549. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.113944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson D., Mathur M.C., Chalovich J.M. The cardiomyopathy mutation, R146G troponin I, stabilizes the intermediate “C” state of regulated actin under high- and low-free Ca(2+) conditions. Biochemistry. 2016;55:4533–4540. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b01359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thierfelder L., Watkins H., Seidman C.E. Alpha-tropomyosin and cardiac troponin T mutations cause familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a disease of the sarcomere. Cell. 1994;77:701–712. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burhop J., Rosol M., Lehman W. Effects of a cardiomyopathy-causing troponin t mutation on thin filament function and structure. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:20788–20794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101110200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakaura H., Morimoto S., Ohtsuki I. Functional changes in troponin T by a splice donor site mutation that causes hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;277:C225–C232. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.2.C225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eisenberg E., Weihing R.R. Effect of skeletal muscle native tropomyosin on the interaction of amoeba actin with heavy meromyosin. Nature. 1970;228:1092–1093. doi: 10.1038/2281092a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chalovich J.M., Johnson D. Commentary: effect of skeletal muscle native tropomyosin on the interaction of amoeba actin with heavy meromyosin. Front. Physiol. 2016;7:377. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinto J.R., Parvatiyar M.S., Potter J.D. A functional and structural study of troponin C mutations related to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:19090–19100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.007021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kobayashi T., Solaro R.J. Increased Ca2+ affinity of cardiac thin filaments reconstituted with cardiomyopathy-related mutant cardiac troponin I. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:13471–13477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509561200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smillie L.B. Preparation and identification of alpha- and beta-tropomyosins. Methods Enzymol. 1982;85:234–241. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(82)85023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hibbs R.E., Talley T.T., Taylor P. Acrylodan-conjugated cysteine side chains reveal conformational state and ligand site locations of the acetylcholine-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:28483–28491. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403713200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spudich J.A., Watt S. The regulation of rabbit skeletal muscle contraction. I. Biochemical studies of the interaction of the tropomyosin-troponin complex with actin and the proteolytic fragments of myosin. J. Biol. Chem. 1971;246:4866–4871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kouyama T., Mihashi K. Fluorimetry study of N-(1-pyrenyl)iodoacetamide-labelled F-actin. Local structural change of actin protomer both on polymerization and on binding of heavy meromyosin. Eur. J. Biochem. 1981;114:33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kielley W.W., Harrington W.F. A model for the myosin molecule. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1960;41:401–421. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(60)90037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weeds A.G., Taylor R.S. Separation of subfragment-1 isoenzymes from rabbit skeletal muscle myosin. Nature. 1975;257:54–56. doi: 10.1038/257054a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lehrer S.S., Ishii Y. Fluorescence properties of acrylodan-labeled tropomyosin and tropomyosin-actin: evidence for myosin subfragment 1 induced changes in geometry between tropomyosin and actin. Biochemistry. 1988;27:5899–5906. doi: 10.1021/bi00416a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen Y., Yan B., Brenner B. Theoretical kinetic studies of models for binding myosin subfragment-1 to regulated actin: Hill model versus Geeves model. Biophys. J. 2001;80:2338–2349. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(01)76204-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Geeves M.A., Chai M., Lehrer S.S. Inhibition of actin-myosin subfragment 1 ATPase activity by troponin I and IC: relationship to the thin filament states of muscle. Biochemistry. 2000;39:9345–9350. doi: 10.1021/bi0002232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Houmeida A., Heeley D.H., White H.D. Mechanism of regulation of native cardiac muscle thin filaments by rigor cardiac myosin-S1 and calcium. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:32760–32769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.098228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kowlessur D., Tobacman L.S. Significance of troponin dynamics for Ca2+-mediated regulation of contraction and inherited cardiomyopathy. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:42299–42311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.423459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blumenschein T.M., Tripet B.P., Sykes B.D. Mapping the interacting regions between troponins T and C. Binding of TnT and TnI peptides to TnC and NMR mapping of the TnT-binding site on TnC. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:36606–36612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105130200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eisenberg E., Kielley W.W. Native tropomyosin: effect on the interaction of actin with heavy meromyosin and subfragment-1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1970;40:50–56. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(70)91044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pemrick S., Weber A. Mechanism of inhibition of relaxation by N-ethylmaleimide treatment of myosin. Biochemistry. 1976;15:5193–5198. doi: 10.1021/bi00668a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murray J.M., Knox M.K., Weber A. Potentiated state of the tropomyosin actin filament and nucleotide-containing myosin subfragment 1. Biochemistry. 1982;21:906–915. doi: 10.1021/bi00534a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Szczesna D., Zhang R., Potter J.D. Altered regulation of cardiac muscle contraction by troponin T mutations that cause familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:624–630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Watkins H., McKenna W.J., Seidman C.E. Mutations in the genes for cardiac troponin T and alpha-tropomyosin in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;332:1058–1064. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504203321603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lassalle M.W. Defective dynamic properties of human cardiac troponin mutations. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2010;74:82–91. doi: 10.1271/bbb.90586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang J., Liu W.L., Xiao J. [Novel mutations of cardiac troponin T in Chinese patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy] Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2011;39:909–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morimoto S., Nakaura H., Ohtsuki I. Functional consequences of a carboxyl terminal missense mutation Arg278Cys in human cardiac troponin T. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;261:79–82. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brunet N.M., Chase P.B., Schoffstall B. Ca(2+)-regulatory function of the inhibitory peptide region of cardiac troponin I is aided by the C-terminus of cardiac troponin T: effects of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations cTnI R145G and cTnT R278C, alone and in combination, on filament sliding. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014;552–553:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Venkatraman G., Harada K., Potter J.D. Different functional properties of troponin T mutants that cause dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:41670–41676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302148200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Messer A.E., Bayliss C.R., Marston S.B. Mutations in troponin T associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy increase Ca(2+)-sensitivity and suppress the modulation of Ca(2+)-sensitivity by troponin I phosphorylation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2016;601:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2016.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tardiff J.C., Factor S.M., Leinwand L.A. A truncated cardiac troponin T molecule in transgenic mice suggests multiple cellular mechanisms for familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;101:2800–2811. doi: 10.1172/JCI2389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chong S.M., Jin J.P. To investigate protein evolution by detecting suppressed epitope structures. J. Mol. Evol. 2009;68:448–460. doi: 10.1007/s00239-009-9202-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Takeda S., Yamashita A., Maéda Y. Structure of the core domain of human cardiac troponin in the Ca(2+)-saturated form. Nature. 2003;424:35–41. doi: 10.1038/nature01780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jin J.P. Evolution, regulation, and function of N-terminal variable region of troponin T: modulation of muscle contractility and beyond. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2016;321:1–28. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.MacFarland S.M., Jin J.P., Brozovich F.V. Troponin T isoforms modulate calcium dependence of the kinetics of the cross-bridge cycle: studies using a transgenic mouse line. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2002;405:241–246. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gomes A.V., Guzman G., Potter J.D. Cardiac troponin T isoforms affect the Ca2+ sensitivity and inhibition of force development. Insights into the role of troponin T isoforms in the heart. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:35341–35349. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204118200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ogut O., Granzier H., Jin J.P. Acidic and basic troponin T isoforms in mature fast-twitch skeletal muscle and effect on contractility. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;276:C1162–C1170. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.5.C1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chandra M., Montgomery D.E., Solaro R.J. The N-terminal region of troponin T is essential for the maximal activation of rat cardiac myofilaments. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1999;31:867–880. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1999.0928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jin J.P., Root D.D. Modulation of troponin T molecular conformation and flexibility by metal ion binding to the NH2-terminal variable region. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11702–11713. doi: 10.1021/bi9927437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pearlstone J.R., Smillie L.B. The interaction of rabbit skeletal muscle troponin-T fragments with troponin-I. Can. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1985;63:212–218. doi: 10.1139/o85-030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schaertl S., Lehrer S.S., Geeves M.A. Separation and characterization of the two functional regions of troponin involved in muscle thin filament regulation. Biochemistry. 1995;34:15890–15894. doi: 10.1021/bi00049a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jha P.K., Leavis P.C., Sarkar S. Interaction of deletion mutants of troponins I and T: COOH-terminal truncation of troponin T abolishes troponin I binding and reduces Ca2+ sensitivity of the reconstituted regulatory system. Biochemistry. 1996;35:16573–16580. doi: 10.1021/bi9622433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pearlstone J.R., Smillie L.B. Identification of a second binding region on rabbit skeletal troponin-T for alpha-tropomyosin. FEBS Lett. 1981;128:119–122. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(81)81095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tanokura M., Tawada Y., Ohtsuki I. Chymotryptic subfragments of troponin T from rabbit skeletal muscle. Interaction with tropomyosin, troponin I and troponin C. J. Biochem. 1983;93:331–337. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a134185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Morris E.P., Lehrer S.S. Troponin-tropomyosin interactions. Fluorescence studies of the binding of troponin, troponin T, and chymotryptic troponin T fragments to specifically labeled tropomyosin. Biochemistry. 1984;23:2214–2220. doi: 10.1021/bi00305a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chong P.C., Hodges R.S. Photochemical cross-linking between rabbit skeletal troponin and alpha-tropomyosin. Attachment of the photoaffinity probe N-(4-azidobenzoyl-[2-3H]glycyl)-S-(2-thiopyridyl)-cysteine to cysteine 190 of alpha-tropomyosin. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:9152–9160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jin J.P., Chong S.M. Localization of the two tropomyosin-binding sites of troponin T. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2010;500:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kranias E.G., Solaro R.J. Phosphorylation of troponin I and phospholamban during catecholamine stimulation of rabbit heart. Nature. 1982;298:182–184. doi: 10.1038/298182a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Noland T.A., Jr., Kuo J.F. Protein kinase C phosphorylation of cardiac troponin I or troponin T inhibits Ca2(+)-stimulated actomyosin MgATPase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:4974–4978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Montgomery K., Mak A.S. In vitro phosphorylation of tropomyosin by a kinase from chicken embryo. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:5555–5560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vahebi S., Kobayashi T., Solaro R.J. Functional effects of rho-kinase-dependent phosphorylation of specific sites on cardiac troponin. Circ. Res. 2005;96:740–747. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000162457.56568.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sumandea M.P., Pyle W.G., Solaro R.J. Identification of a functionally critical protein kinase C phosphorylation residue of cardiac troponin T. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:35135–35144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306325200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schlecht W., Zhou Z., Dong W.J. FRET study of the structural and kinetic effects of PKC phosphomimetic cardiac troponin T mutants on thin filament regulation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014;550-551:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.