Abstract

Mechanotransduction is likely to be an important mechanism of signaling in thin, elongated cells such as neurons. Maintenance of prestress or rest tension may facilitate mechanotransduction in these cells. In recent years, functional roles for mechanical tension in neuronal development and physiology are beginning to emerge, but the cellular mechanisms regulating neurite tension remain poorly understood. Active contraction of neurites is a potential mechanism of tension regulation. In this study, we have explored cytoskeletal mechanisms mediating active contractility of neuronal axons. We have developed a simple assay in which we evaluate contraction of curved axons upon trypsin-mediated detachment. We show that curved axons undergo contraction and straighten upon deadhesion. Axonal straightening was found to be actively driven by actomyosin contractility, whereas microtubules may subserve a secondary role. We find that although axons show a monotonous decrease in length upon contraction, subcellularly, the cytoskeleton shows a heterogeneous contractile response. Further, using an assay for spontaneous development of tension without trypsin-induced deadhesion, we show that axons are intrinsically contractile. These experiments, using novel experimental approaches, implicate the axonal cytoskeleton in tension homeostasis. Our data suggest that although globally, the axon behaves as a mechanical continuum, locally, the cytoskeleton is remodeled heterogeneously.

Introduction

Neurites are axisymmetric structures with extreme aspect ratio and long lengths. Developing neurites experience mechanical stretch via growth-cone-mediated towing (1) and later, after the formation of connections, from tissue expansion associated with animal growth. Mechanical tension along neurites has been demonstrated to affect various neuronal processes, including growth (2), retraction (3), synaptic vesicle dynamics (4, 5), synaptic transmission (6), excitability (7), and network formation (8, 9). Though the focus of the axon mechanics field has been on axonal stretch as a feedback mechanism for various biological processes, not much is known about the mechanisms maintaining and regulating neurite tension.

The role of the axonal cytoskeleton, its organization, and its dynamics in the regulation of tension are beginning to emerge. The axonal shaft is filled with heavily cross-linked, polarized bundles of microtubules with the plus end oriented toward the growth cone (10). F-actin is organized by cross-linkers and myosins into a thin cortical layer underneath the plasma membrane (11). In mature neurites, actin and spectrin form a periodic, membrane-associated skeleton ring (12, 13) and, together with microtubules, are known to protect neurites from mechanical stress (14). Other organizations of F-actin such as actin trails, patches, and dynamic actin hotspots have also been reported in axons (15). These recent observations and others show that the axonal cytoskeleton is highly dynamic, and it is likely that remodeling of the cytoskeleton and membrane-cytoskeleton complexes will be central to the regulation of axonal tension.

Several studies have demonstrated that neurites, including axons, actively maintain a rest tension (2, 16, 17). Neuronal rest tension has largely been studied using microneedle-based manipulations (2, 18) and ablation studies (16). In microneedle-based axon slackening experiments, the recovery tension often exceeded the initial values, suggesting active generation of tension in neurons (2). In axotomy-induced retraction-based studies, axonal shortening was found to be ATP dependent (16). Later, laser-ablation-induced axonal retraction was demonstrated to be dependent on actomyosin contractility (19). In PC12 neurites, retraction studies revealed that actin was involved in generating tension, whereas microtubules had a resisting function (20). A similar balancing function between actomyosin contractility and microtubule resistance has been recently identified in contracting Drosophila neurons (21). Active contraction as a potential mechanism to regulate axonal rest tension has been suggested from studies on PC12 neurites and modeled by invoking active involvement of molecular motors (18).

Most of the abovementioned studies have employed acute and localized perturbations, which may invoke local responses to these perturbations or damage. For example, axotomy is known to locally elevate calcium (22) and, in turn, may induce activation of myosins (19) and calpain proteases (23). A study attempting to circumvent these issues employed flow stretching of PC12 neurites and reported oscillations in the strain rate suggestive of active behavior (24). In the current study, we have developed simple assays that are globally acting and nonintrusive compared to microneedle or ablation strategies. We use these methods to investigate the origins of axonal contractility in vertebrate sensory neurons. Our results suggest that axons are intrinsically contractile, and axonal contraction is driven primarily by actomyosin activity.

Materials and Methods

Dissection and cultures

Fertilized white Leghorn chicken eggs were obtained from Venkateshwara Hatchery Private Limited (Pune, India). All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER) Pune, Pune, India. Nine- or 10-day-old chick embryos were used to isolate dorsal root ganglia (DRG). Dissections were carried out in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4) under a dissecting microscope inside a horizontal laminar flow hood. Twelve to 14 DRGs were removed from both sides of the spinal cord and collected in L15 medium (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA). The tissue was centrifuged at 3000 rotations per minute for 3 min before the medium was removed, and 1× trypsin (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) was added. Trypsinization was undertaken for 20 min at 37°C. After trypsinization, the tissue was centrifuged at 3000 rotations per minute for 3–5 min before removal of trypsin and washed with L15 medium. The dissociated neurons were plated on poly-L-lysine-coated (1 mg/mL PLL; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) 35-mm cover-glass-bottomed petri dishes in 1.5 mL of serum-free media (L15 containing 6 mg/mL glucose (Sigma-Aldrich), 1× glutamine (Gibco), 1× B27 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 20 ng/mL nerve growth factor (Gibco) and 1× Penstrep (Gibco)). The neuronal culture was incubated for 48 hr at 37°C before deadhesion experiments. Cells were grown in serum-free media until half an hour before deadhesion experiments to increase the occurrence of curved axons during the initial growth phase (see next section for details).

For microcontact printing experiments, the cover glasses were patterned (as described below) before plating the neurons. These experiments were performed in media containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco).

Trypsin deadhesion, imaging, and analysis

In initial experiments, we grew DRG neurons in the presence of serum before trypsin deadhesion. However, subsequently, we took advantage of the fact that neurons cultured without serum have a much greater frequency of neurites showing curved trajectories (25) and thus improved the throughput of our experiments. Neurons were grown for 48 hr without serum, followed by refeeding 10% FBS 30 min or 2 hr before trypsinization. In all three conditions (viz., cultured with serum or without serum followed by 30 min or 2 hr serum refeeding), a straightening response was seen in response to axonal deadhesion (Fig. S1). The contractility of 30 min and 2 hr serum-refed axons were comparable. Thus, all inhibitor-based perturbation experiments were conducted after 30 min of serum treatment.

To perform trypsin deadhesion experiments, 10% FBS (Gibco) was added to the neurons grown in serum-free media and incubated for a further 30 min at 37°C. Immediately before trypsin-induced deadhesion, serum-containing media were removed, and the cultures were washed thrice in prewarmed serum-free L15 and replaced with 1 mL of serum-free L15. Isolated curved axons were identified, and trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to a final concentration of 5×. Upon trypsin treatment, axons deadhere and show a straightening response. The axonal deadhesion precedes the detachment of soma and growth cones from the substrate. Neurons were imaged at 37°C using differential interference contrast microscopy using a 40× oil objective on an Olympus IX81 system (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a Hamamatsu ORCA-R2 CCD camera (Hamamatsu, Hamamatsu City, Japan). Images were recorded at a one frame per second acquisition rate using the Xcellence RT (Olympus Corporation) software. Typically, straightening starts after 10–20 s of trypsin addition, and imaging was continued till there was no further length change or the axonal ends (soma or growth cone) detached. Images were exported to ImageJ, and lengths were measured using the segmented line tool at every 10-s interval.

The following inclusion criteria were used to select axons for evaluation of axonal contractility.

-

1)

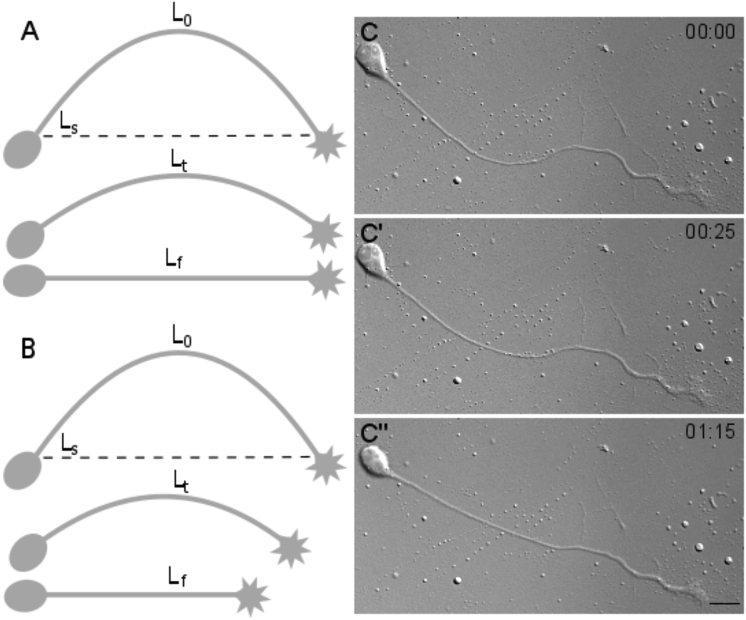

Axons showing significant curvature, presumably due to attachments along their lengths, were chosen for axon-straightening experiments (Fig. 1 A). Axonal segments having obvious branches were not considered, as the branches may hinder contraction.

-

2)

If the growth cone retracted concomitantly with a reduction in axonal curvature, then such data were included in our analysis. In these cases, the assumption is that the axonal shortening, evident from the reduction of curvature, is causing the weakly attached growth cone to be pulled backward (Fig. 1 B).

-

3)

If the growth cone or soma detached and retracted before the reduction in axonal curvature, then these were not included in the analysis.

Figure 1.

Trypsin-induced axonal deadhesion and straightening. (A) A schematic representation of axonal contraction upon trypsin-induced deadhesion is shown. (B) A schematic representation of axonal contraction concomitant with tip retraction upon deadhesion is shown. Ls is the straight-line distance between two ends at time 0. L0, Lt, and Lf are lengths in the first frame, an intermediate frame, and the final frame, respectively. (C–C″) Representative frames from time-lapse imaging of an axon straightening after trypsin-induced deadhesion are shown. Although the growth cone and cell body do not show significant movement, the axonal segment straightens. Trypsin is added at time 0. The time stamp shows minutes: seconds elapsed. Scale bars, 15 μm.

In these experiments, the axon lengths ranged from 70 to 180 μm, and a 5–35% decrease in length was observed upon deadhesion.

Neurons grown on patterned substrates

Patterned substrates were generated using microcontact printing. Silicon masters with 20-μm-diameter depressions spaced 50 or 70 μm apart were procured from Bonda Technology Pte. (Singapore, Singapore). Polydimethylsyloxane (PDMS) (Dow Corning, Midland, MI) stamps were made from the master by using a previously published protocol (26). Sterile PDMS stamps were washed with isopropanol and dried in the laminar flow hood. Laminin (20 μg/mL), fibronectin (100 μg/mL), and rhodamine-labeled bovine serum albumin (10 μg/mL) were mixed and used for “inking” the PDMS stamp. The protein mixture was applied onto the stamp and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. After removal of excess protein solution, the stamps were used to pattern cover-glass-bottomed 35-mm petri dishes. Phosphate-buffered saline was added immediately after printing to avoid drying of the patterns until neurons were plated.

For studies involving axons straightening on patterned substrates, axons were imaged after 8 hr or overnight incubation in serum-containing medium. Neurons were imaged at 37°C in differential interference contrast mode using 10× or 40× objective at 15-s intervals. Images were exported to ImageJ, and axonal lengths were measured using the segmented line tool.

Drug treatments

Neurons were treated with 30 μM blebbistatin (-enantiomer; Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 hr before the straightening experiments. For actin depolymerization and microtubule depolymerization experiments, 0.6 μM latrunculin A (Sigma-Aldrich) or 16 μM/33 μM nocodazole (Sigma-Aldrich) were added to the cultures 15 min before trypsin treatment. All drugs were dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO). Control experiments were undertaken to test the effect of similar volumes of DMSO on straightening kinetics.

The efficacy of latrunculin A and nocodazole treatment was confirmed using phalloidin staining and α-tubulin immunofluorescence, respectively (see Supporting Materials and Methods for details).

Labeling of mitochondria

Neurons were cultured for 48 hr, followed by serum induction as described above. After 30 min of serum induction, cells were incubated with 50 nM MitoTracker Green FM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for 2 min, followed by two washes using L15 (Gibco) and minimum 30 min incubation in L15 before imaging. Images were acquired at every 1-s interval in green fluorescent protein channel using a 40× oil objective on an Olympus IX81 system equipped with a Hamamatsu ORCA-R2 CCD camera (Hamamatsu).

Mitochondria tracking and analysis

We developed a MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA)-based code to track labeled mitochondria. Mitochondria were tracked every 10 s, as this was optimal for differentiating docked and mobile mitochondria. The Simple Neurite Tracer plugin (http://imagej.net/Simple_Neurite_Tracer) was implemented in Fiji (https://imagej.net/Fiji) to trace the axon and obtain the coordinates along its length at each time point. These images, with their corresponding coordinate files, were saved as .jpg and .swc files, respectively. Images and their corresponding .swc files were imported to MATLAB (The MathWorks). Coordinates from the .swc files were used to obtain the normal to the path forming the neurite trajectory at each point, and the vector of pixels along this normal was determined. The location of the intensity maxima along this vector of pixels at each point was used as the coordinate of the neurite at that point. The vectors of pixels along the normals were also stored for making kymograph plots. The intensity values per pixel along the neurite, using the coordinates obtained by the procedure described above, were used to identify the locations of the mitochondria. To eliminate detection of small spurious local peaks as mitochondria, a smoothing filter was used. Intensity series from all images of a neurite were resampled to have the same length as the longest (the first image). These interpolated series were used to reliably identify peaks corresponding to mitochondria that were consistently present throughout the experiment (Fig. S6). The coordinates of the detected mitochondria were scaled back to get their coordinates in the original scale. These position data were used to calculate local strains.

Definitions of parameters

We characterized the length minimization response by evaluating the evolution of the strain in the axonal segment (Fig. 1, A and B).

For quantitative comparison of data under various cytoskeleton-perturbing drug treatments, we have used contraction factor (Cr) as a time-independent measure of the extent of axonal shortening (21) (Fig. S2),

Lf = saturation length of the axon after deadhesion, measured from the last frame of recording.

L0 = length of the axon at the time of trypsinization (t = 0).

Ls = straight line distance between the endpoints of the axonal segment at time 0.

Lt = length of the axon at time t.

If there is no length change, then Cr will be 0, Cr = 1 indicates straight end-to-end geometry, and values between zero and one indicate partial straightening. And if length reduction is accompanied by tip retraction, then Cr could exceed 1.

Statistics

Curve fitting and plotting of strain versus time plots were done in MATLAB (The MathWorks) using the cftool. Average strain plots were plotted in Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Unpaired t-test was used to compare contraction factors using the GraphPad Prism 5 software.

Results and Discussion

Axons show strain relaxation and straightening upon trypsin-mediated detachment

To evaluate the axonal strain without acute mechanical perturbations or damage, we developed an assay involving the straightening of curved neurites in culture. In this assay, primary chick DRG neurons are cultured on poly-L-lysine-coated glass substrates, and axonal strain is evaluated after trypsin-induced axonal deadhesion. Upon the addition of 5× trypsin, axons detach faster from the substrate than the growth cone or the neuronal soma. Presumably, the relatively smaller contact surface of the axon supports fewer attachments compared to the growth cone or cell body. We find that in response to trypsin-mediated axonal deadhesion, straightening is evident in the axonal segment, and progressive axonal shortening results in length minimization (Fig. 1, A–C; Video S1). Typically, the reduction in curvature is apparent within 10–20 s of trypsin addition, and it takes 1–5 min for the axonal segment to reach the minimal length.

This video shows footage of axonal straightening after trypsin-mediated deadhesion.

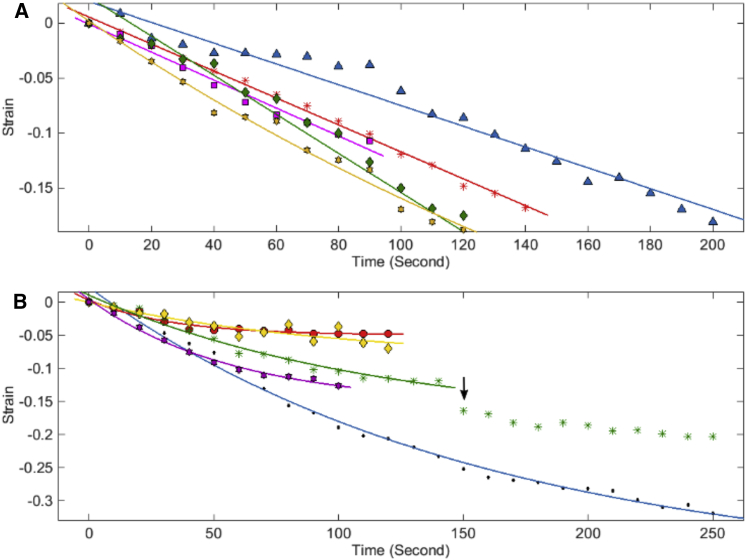

To evaluate the length-shortening response, we used strain as a parameter (strain = (Lt − L0)/L0, where L0 = length of the axon at the time of trypsinization (t = 0) and Lt = length of the axon at time t). Strain is zero at the time of trypsin addition, and the negative strain reflects the length-shortening response. Interestingly, neurons show heterogeneous behavior. Some neurons showed a linear change in strain with a constant rate (Fig. 2 A), whereas the other neurons displayed an exponential strain relaxation response (Fig. 2 B). In the latter case, the strain saturates at different values. These different trends could be due to underestimation of the data for neurons showing a linear response due to deadhesion of the ends as an axon straightens or differences in extent of length change. It is also possible that these differences arise from heterogeneity in intrinsic contractility within individual neurons. Heterogeneity in recovery of rest tension after slackening has been previously documented in chick DRG (2). Although some neurons recovered to tension values higher than the initial, others failed to reach the initial value. Further, repeated slackening of the same neurons suggested a tendency to behave similarly (2). These observations were independent of initial length or initial tension and reinforce the possibility of intrinsic differences in contractility between neurons.

Figure 2.

Axonal strain relaxation upon deadhesion. Examples of strain relaxation of axons upon deadhesion showing both (A) linear and (B) nonlinear responses are shown. Strain = (Lt − L0)/L0, where L0 and Lt are lengths at time 0 and at time t, respectively. Different axons are marked in different colors. Symbols indicate actual data, whereas continuous lines are linear and single-exponential fits. The arrow indicates a sudden drop in the strain in that axon as an effect of delayed local detachment; hence, data points further are not included in the fit. To see this figure in color, go online.

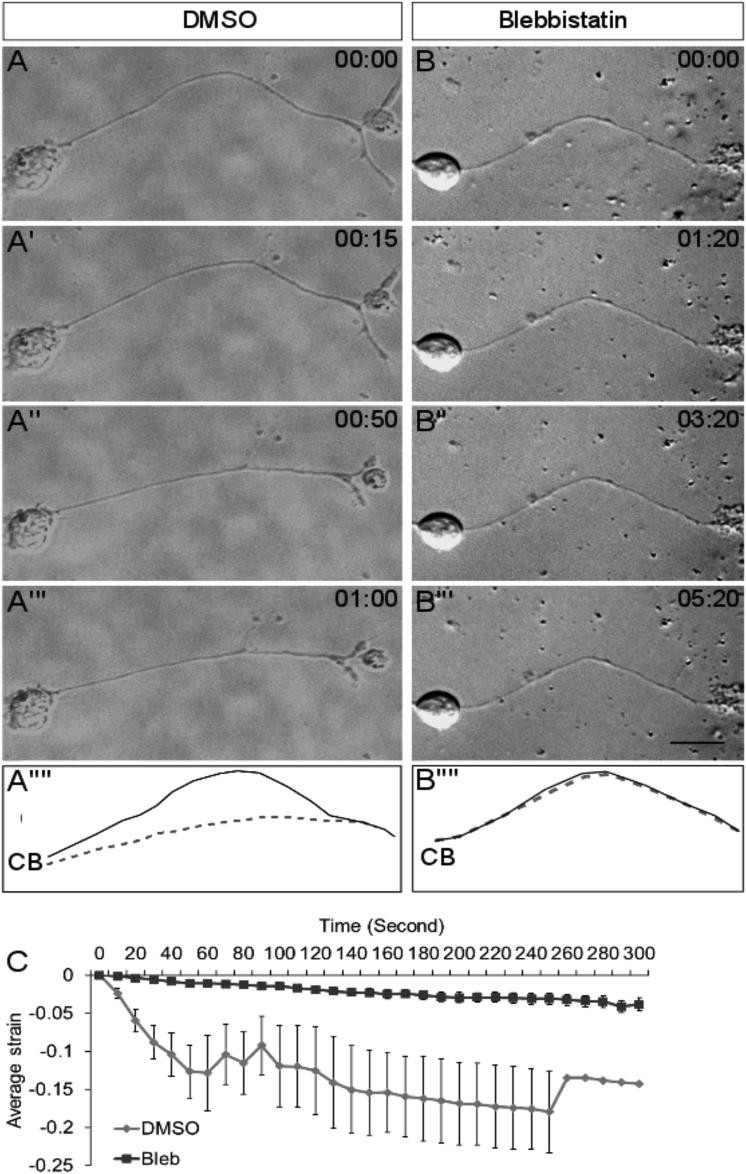

Axonal straightening after deadhesion is actomyosin dependent

To investigate the contribution of actomyosin contractility in axonal straightening, a specific small-molecule inhibitor of myosin II, blebbistatin, was employed. Curved neurons pretreated with 30 μM blebbistatin for 1 hr failed to straighten upon trypsin-induced deadhesion (Fig. 3, B–B″″ and C; n = 10). Matched DMSO controls, on the other hand, showed the expected axonal straightening (Fig. 3, A–A″″; n = 9). To directly compare the two treatments, we used a time-independent parameter for the extent of contraction. Comparison of this contraction factor (see Materials and Methods for definition) between DMSO and blebbistatin-treated axons also indicated that inhibition of myosin II prevented deadhesion-induced axonal straightening (Fig. S2; p = 0.0001).

Figure 3.

Axonal contraction is dependent on myosin II activity. (A–A″″) Representative frames from time-lapse imaging of a DMSO-treated control axon are shown. (B–B″″) Representative frames from time-lapse imaging of an axon pretreated with blebbistatin (30 μM) for 1 hr before trypsin addition are shown. (A″″) and (B″″) show the line trace of the axon shown in the first frame (solid line) and last frame (dashed line) of the representative micrographs of both treatments. CB indicates the position of the cell body. Trypsin is added at time 0 for each treatment. Time stamp shows minutes: seconds elapsed. Scale bars, 15 μm. (C) The average strain rate is reduced upon blebbistatin (Bleb) treatment (n = 10) compared to DMSO-treated controls (n = 9). Error bars indicate SE of the mean.

These experiments suggested that axonal strain relaxation observed upon axonal deadhesion is due to contractility of axons driven by myosin II activity.

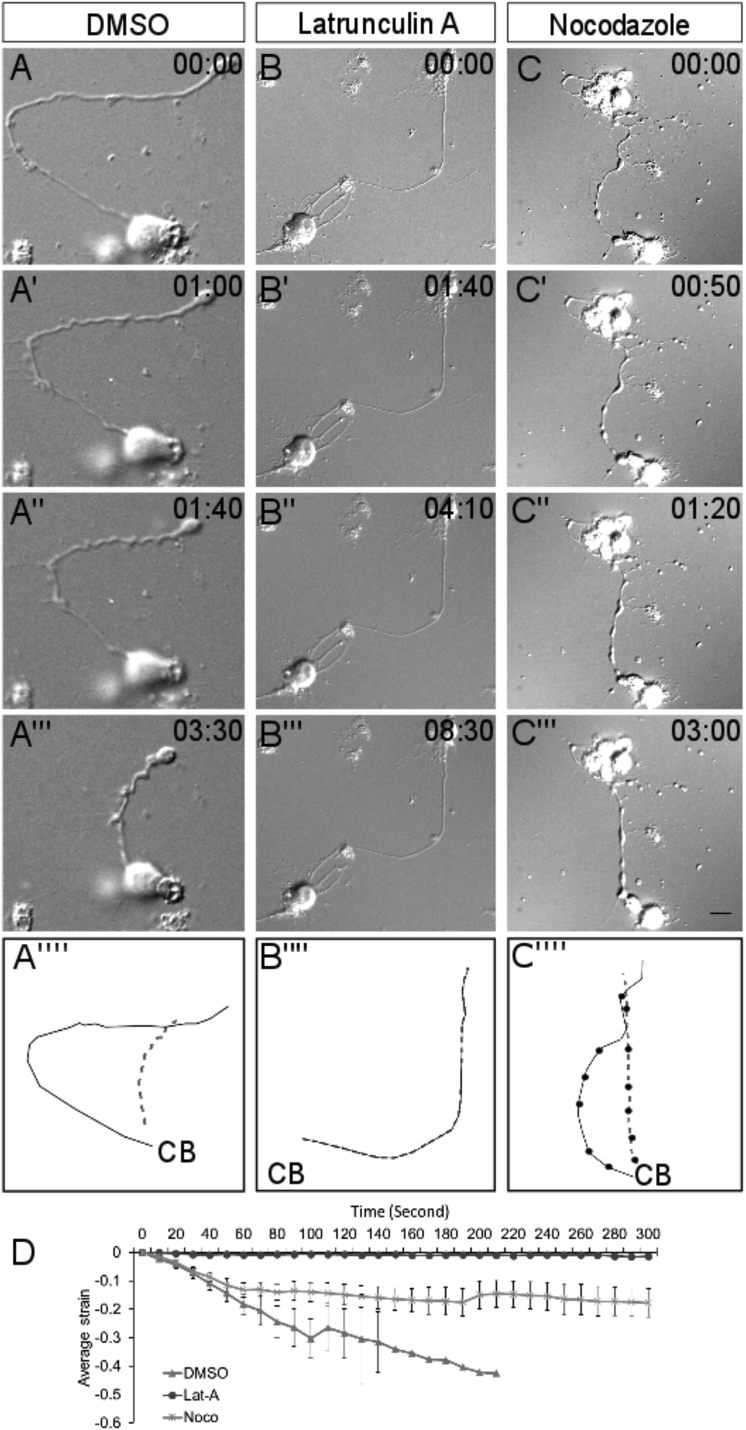

We next evaluated the contribution of axonal F-actin by using latrunculin A (Lat A), which depolymerizes F-actin by binding to actin monomers and preventing them from polymerizing. Lat A (0.6 μM) pretreatment for 15 min was used to inhibit actin polymerization before trypsin-induced detachment and resulted in an expected decrease in phalloidin-staining intensity along the axon (Fig. S3 B). Lat A pretreatment completely abolished axonal contractility (Fig. 4, B–B″″; n = 7), whereas matched DMSO controls showed straightening upon trypsinization (Fig. 4, A–A″″; n = 7). Direct comparison of contraction factors also indicated that axonal F-actin is essential for neurite contractility (Fig. S3 A; p < 0.0001).

Figure 4.

Effect of F-actin and microtubule depolymerization on axonal contraction. (A–A″′) Representative frames from time-lapse imaging of a DMSO-treated control axon are shown. (B–B″′) Representative frames from time-lapse imaging of an axon pretreated with Lat A (0.6 μM) for 15 min before trypsin addition are shown. (C–C″′) Representative frames from time-lapse imaging of an axon pretreated with nocodazole (33 μM) for 15 min before trypsin addition. (A″″), (B″″), and (C″″) show the line trace of the axon shown in the first frame (solid line) and last frame (dashed line) of the representative micrographs of the three treatments. CB indicates the position of the cell body. Trypsin is added at time 0 for each treatment. Time stamp shows minutes: seconds elapsed. Scale bars, 15 μm. (D) Compared to DMSO controls (n = 7), average strain rate is strongly reduced upon treatment with Lat A (n = 7). Treatment with nocodazole (Noco; n = 9) also reduces axonal contractility. Error bars indicate SE of the mean.

We imaged the blebbistatin- and Lat A-treated neurons for up to 10 min to find out if axonal contractility was delayed. However, no late response was observed for either blebbistatin- or Lat A-treated neurons. To ensure trypsin deadhesion was not affected by drug treatment, fresh medium was flowed into the culture dish at the end of the imaging period to generate flow disturbances. Axonal segments were found to be detached and floppy, indicating deadhesion (data not shown).

Taken together, these experiments implicate active actomyosin contractility in mediating axonal straightening. Actomyosin-activity-driven pulling forces have been previously demonstrated in axonal retraction (19, 27). Consistent with the significant actomyosin contribution observed in our studies, disruption of F-actin has been previously reported to reduce axonal rest tension (20). In fly motor neurons, too, axonal contraction is driven by actomyosin contractility (21), supporting our results using a different experimental paradigm in vertebrate neurons.

Unlike the abovementioned reports, our study avoids local/acute perturbations that may trigger axonal entry of extracellular calcium and in turn induce actomyosin contractility. The current study, using a strategy to probe axonal mechanics without localized manipulations, further underscores the importance of actomyosin activity in mediating axonal contractility.

Effect of microtubule depolymerization on axonal contraction

The axonal shaft is filled with a cross-linked bundle of microtubules that contribute to multiple aspects of axonal behavior and mechanics (28). To test the role of the microtubule cytoskeleton in axonal contractility, neurons were pretreated with the microtubule-depolymerizing agent nocodazole (33.3 μM for 15 min; Noco, Glenwillow, OH). Interestingly, nocodazole pretreatment did not block axonal contraction (Fig. 4, C–C″″; n = 9), though the rate of contraction appeared to be reduced compared to the DMSO control (Fig. 4 D; n = 7). Direct comparison of the contraction factor (see Supporting Materials and Methods for definition) also indicated that axonal contractility is affected upon nocodazole treatment (Fig. S3 A; p = 0.0204). Similar experiments using a lower dose of nocodazole were consistent with the earlier results. Pretreatment with 16 μM nocodazole did not abolish axonal contraction (Fig. S4, B–B″) as compared to matching DMSO controls (Fig. S4, A–A″). The extent of contraction is comparable (Fig. S4 D); however, the rate of contraction was reduced (Fig. S4 C). Both doses of nocodazole treatment resulted in a reduction in α-tubulin-staining intensity (Figs. S3 C and S4 E), as expected for microtubule disruption.

In a recent study in ex vivo preparations of fly embryos, disruption of microtubules led to faster axonal contraction of motor neurons in response to slackening (21). In our study, microtubule depolymerization did not prevent axonal shortening, but the rate of contraction was slightly reduced. This discrepancy may be due to intrinsic differences between invertebrate and vertebrate neurons. In addition, nocodazole treatment resulted in most neurites exhibiting a beaded morphology (Fig. 4 C). This is consistent with previous observations (29) and confirms the efficacy of nocodazole. This significant change in axonal morphology may adversely affect the contractility by indirectly affecting the continuity of the actomyosin network. Further, nocodazole-treated axons also showed thin membrane tethers as they retracted (Fig. S3, D–D′). Similar observations have been made previously (29), and it is likely that these tethers hinder the contraction of nocodazole-treated neurons.

As axons self-shorten under actomyosin-driven contraction, microtubules appear to be under compression and possibly accommodate the length reduction by sliding against each other (29). The slightly reduced contraction rate seen upon microtubule depolymerization is probably a secondary effect of altered morphology (Figs. S3 D and S4), which precludes a clear evaluation of microtubule function in our experimental system.

It is possible that curved bundles of microtubules in curved axons play an active role in straightening in conjunction with the actomyosin machinery. However, whether individual microtubules exist in curved configurations in axons is unknown. Further, our experiments do not rule out the possibility that microtubule depolymerization indirectly disrupts the axonal actomyosin organization and thereby damps the contractility. In the future, studies targeted at evaluating the contribution of mechanisms regulating microtubule sliding and force-dependent remodeling and subsequent reassembly to axonal contractility are likely to generate important insights.

Cytoskeletal strain is heterogeneous along the axon

To evaluate cytoskeletal deformations upon trypsin-mediated deadhesion and straightening, we tracked the position of labeled docked mitochondria present along axons. Mitochondrial interactions with actin, microtubules, and neurofilaments have been reported previously and form the basis of several studies involving the use of docked mitochondria as a marker for cytoskeletal deformations (30, 31, 32). In neurons, docked mitochondria have been established as a reliable marker for cytoskeletal dynamics in stretch (33) and elongation (34) paradigms. Mitochondrial responses are consistent with other readouts for cytoskeletal dynamics in these studies.

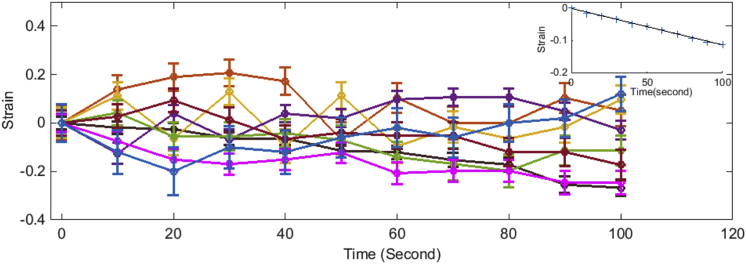

MitoTracker-labeled axons were used in our straightening assay to investigate local cytoskeletal dynamics (Fig. S5). Tracking of mitochondria using conventional kymography tools was not possible because the axon itself shortens. We used custom-written code to track the positions of mitochondria and calculate local strains between adjacent mitochondria pairs as a function of time. This local strain in this analysis is defined as

where ΔLi is distance between the i-th pair of adjacent mitochondria (indexed sequentially from one end) and t is time.

The variations in local strain did not show any observable distal to proximal trend (n = 8). The local strains for pairs of mitochondria for an axon are shown in Fig. 5 (inset shows the axonal strain). Although the cumulative sum of the local strains was negative, at any given time both positive and negative strains were observed along the same axon, and these values fluctuated with time (a plot showing instantaneous strains for the same mitochondrial pairs is shown in Fig. S7 A). Interestingly, there were several instances in which a mitochondrial pair was contracting, but the other pairs were observed to be dilating (Figs. 5 and S7 A). These data suggest that the axonal cytoskeletal is not contracting as a uniform whole but is highly heterogeneous.

Figure 5.

Intermitochondrial strains show heterogeneous response. Plotting the evolution of strain between mitochondrial pairs (adjacent pairs numbered from soma to growth cone) of a randomly selected axon as it straightens is shown. The data reveal instances of contraction in one pair of mitochondria being concomitant with an extension in another pair, and occasionally contraction/extension in two pairs occur together, for example, the purple and blue pairs and also the orange and dark pink pairs. The inset shows that the net axonal strain decreases steadily with time compared to the local strains. Error bars are standard deviations of natural mitochondrial fluctuations observed in six live axons recorded for a similar period of time without inducing deadhesion. To see this figure in color, go online.

To distinguish the strain dynamics upon contraction from baseline mitochondrial fluctuations, we imaged mitochondria-labeled axons without inducing trypsin-mediated deadhesion (Fig. S6, A–A″). Minimal strain fluctuations at similar timescales were observed in these experiments (Fig. S6 B). As expected, the average instantaneous strain was significantly different and negative in axons undergoing straightening as compared to axons not undergoing straightening (no trypsin-mediated deadhesion; Fig. S7 B; p=0.0009). Comparison of variances between axons undergoing straightening to those not treated with trypsin also revealed an increase in intermitochondrial strain variance, confirming the heterogeneous response of the cytoskeleton over and above baseline fluctuations in mitochondrial positions (Fig. S7 C; p=0.0001).

A similar heterogeneous nature of cytoskeletal strain has been reported previously in axons under imposed uniaxial stretching (33). This study suggested that the location of axonal adhesion sites with the substrate could contribute to the heterogeneity in subcellular strain. However, in our assay, axonal segments are detached from the substrate and therefore preclude this possibility. Rather, our study suggests that differences in local material properties of the cytoskeleton, including spatiotemporal variability in actomyosin activity, may contribute to the strain heterogeneity observed during axonal contraction.

In vivo, the heterogeneous response seen along axons might be important for localized regulation of various processes such as neurite branching, adhesion dynamics, and fasciculation. So far axonal contraction studies have been largely limited to the evaluation average properties, like for force or bulk strain. We show that actomyosin-based contractility drives axonal contraction, but the subcellular response is heterogeneous.

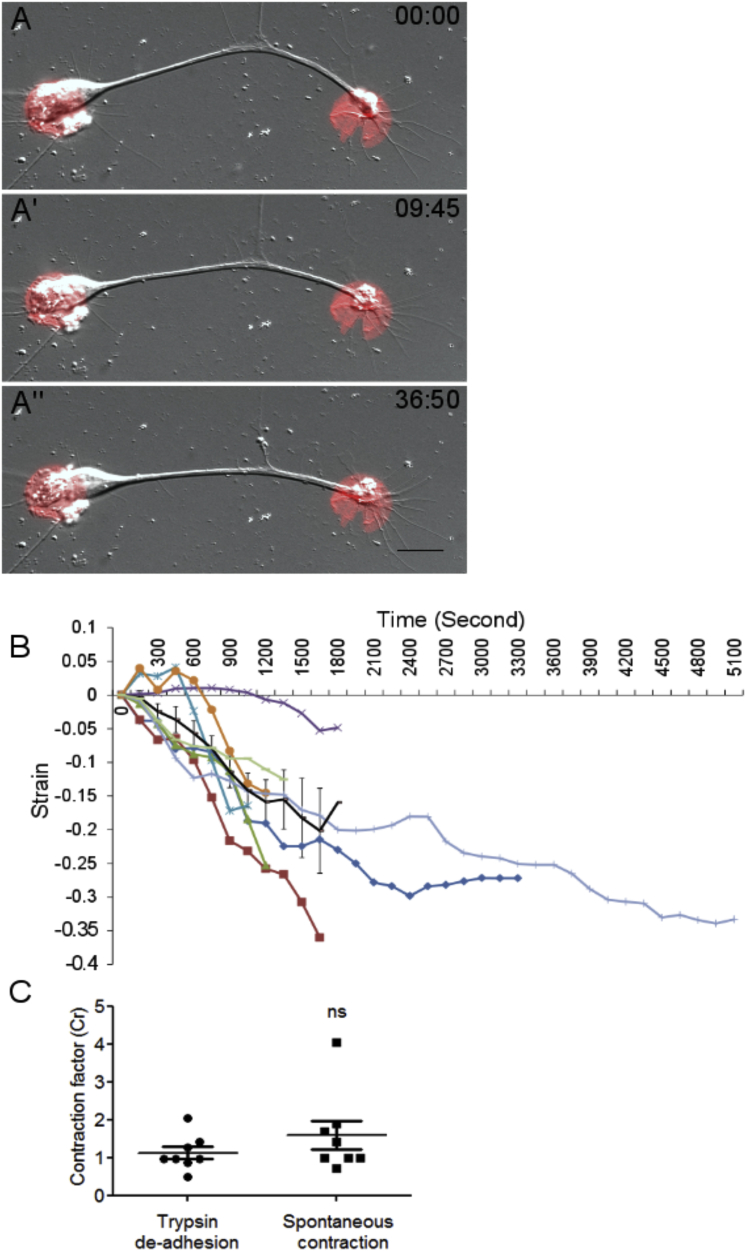

Axons show spontaneous contractility between isolated adhesion sites

Axonal trajectories and configuration are determined by the directional translocation of the growth cone, which can be biased by local differences in environmental cues, and the resistance of the axonal shaft to bending (35). The intrinsic contractility of neurites would tend to result in straight axons unless this is offset by attachments with the substrate along the axon or branches. In trypsin-mediated detachment experiments, attachments along the axons are removed, allowing the axonal actomyosin-machinery-driven contraction to minimize length and curvature. We wanted to investigate whether axons growing in vitro also show spontaneous straightening due to intrinsic contractility without any external perturbation such as trypsin-mediated deadhesion.

To investigate spontaneous axonal contractility, we grew neurons on patterned substrates with isolated islands of extracellular matrix proteins (laminin and fibronectin). These experiments were done in serum-containing media. These islands represented isolated sites of high adhesion relative to the intervening space. We observed that axonal segments often had initially curved trajectories between two islands. However, with time, axonal contraction was established in the segment spanning the two islands, resulting in the reduction of curvature and length (Fig. 6; n = 8; Video S2). In examples in which one end of the axonal segment was the growth cone, axonal contraction resulted in straightening of the segment without any obvious growth-cone movement (Fig. 6, A–A″). This precludes growth-cone-towing-driven tension buildup on the axon and suggests that axons are intrinsically contractile. We observed straight axonal segments for substantial periods of time and confirmed that straight axons remain straight and the observed spontaneous straightening is not random shape changes (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Spontaneous contraction of axons. (A–A″) Representative micrographs from time-lapse imaging of a DRG axon spontaneously straightening between two circular adhesive islands containing laminin and fibronectin are shown. The time stamp shows minutes: seconds elapsed. Scale bars, 15 μm. (B) The evolution of strain with time for eight axons and the average strain plotted with error bars indicating SE of the mean is shown. In some axons, positive strain is observed initially before the axon begins to shorten (Fig. 6B). This is because this assay relies on slow, spontaneous deadhesion, unlike the acute induction of deadhesion by trypsin. (C) The comparison of contraction factor (see Materials and Methods for definition) suggests that the extent of spontaneous contraction between adhesive sites (n = 8) is comparable to that observed during trypsin-induced deadhesion (n = 8). Unpaired t-test was used to compare the means. The error bar represents SE of the mean; ns, not significant. To see this figure in color, go online.

This video shows footage of spontaneous axonal contraction.

The spontaneous shortening observed in these experiments progressed slowly, typically taking tens of minutes to an hour or two, which is significantly slower than trypsinization-induced contraction (Fig. 6 B). This delay suggests that detachment along axons is rate limiting in unperturbed axonal contractions. As the contraction factor (see Materials and Methods for definition) is a parameter for the extent of contraction, we used it to compare between spontaneous and deadhesion-induced contractility. The contraction factor was comparable between the two groups (Fig. 6 C), suggesting a similar degree of contraction in the two assays.

Straightening of axonal segments without appreciable growth cone movement implicates axon-intrinsic contractile mechanisms as opposed to growth-cone-generated forces in axonal-length minimization. A previous study using locust neurons has described a similar assay using islands of carbon nanotubes on quartz sheets. Axonal segments were found to straighten between islands, and branches along the contracting segment were retracted concomitant with the development of tension (8).

Conclusions

We have developed a simple assay to evaluate axonal contractility that avoids local acute mechanical perturbations and instead uses trypsin to detach curved axonal segments from the substrate. In addition, we have developed a microcontact-printing-based assay to assess spontaneous tension development along axonal segments.

Collectively, our data suggest that axons are inherently contractile and tend to minimize their length unless opposed by adhesions along their length. Upon the release of adhesions, intrinsic contractility drives the system toward minimal length. Our study implicates the actomyosin system as the major driver of contractility. Analysis of subcellular strain using docked mitochondria to evaluate local axonal strain shows that the contractility is heterogeneous along the axonal length.

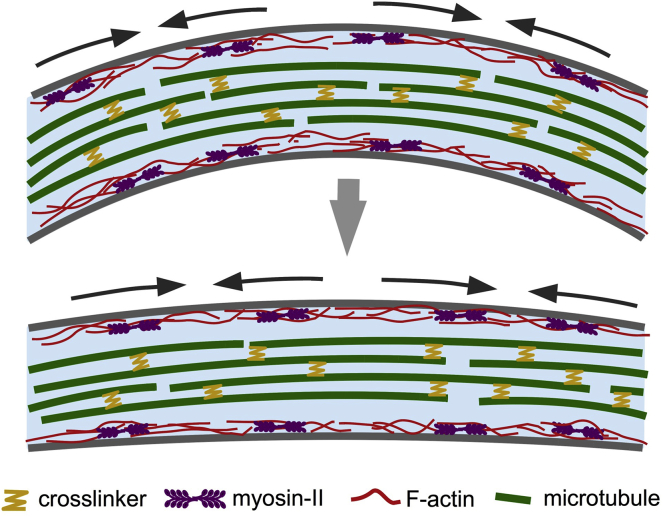

This study highlights the necessity of identifying the detailed organization of the axonal actomyosin system. Recent advances in super-resolution microscopy have revealed a membrane-associated periodic skeleton (MPS) comprising alternating βII spectrin and F-actin rings (12, 13). Using stimulated emission depletion nanoscopy, we evaluated the prevalence of βII spectrin (immunostained with an anti-βII spectrin antibody) and F-actin (live axons stained with the cell-permeable actin probe, SiR-Actin) MPS in chick DRG axons grown for two days in vitro (DIV). These studies revealed that βII spectrin (Fig. S8) and F-actin (Fig. S9) MPS were not prevalent in two-DIV chick DRG axons with only a weak periodic organization (Figs. S8 and S9). In contrast, later-stage axons (five DIV) had clear and extended MPS along the entire axon length (Figs. S8 E and S9 E). Our observations are in line with observations in mammalian neurons in culture in which MPS is abundant only in late stages (10 DIV), whereas earlier stages do not show such organization (36, 37). At two DIV, F-actin labeling is diffuse and inhomogeneous along the axon. F-actin patches and elongated bundles were occasionally observed. We further evaluated myosin distribution using an antibody against phosphorylated myosin light chain (pMLC) and stimulated emission depletion nanoscopy. pMLC was found to have a punctate distribution along the length of the axons (Fig. S10). A recent study had also reported pMLC distribution along the entire length of three-DIV rat hippocampal axons (38). The latter study and our results also indicate that pMLC is not commonly colocalized with the F-actin patches.

Spectrin is known to be sensitive to axial tension and has been demonstrated to regulate rest tension in worm neurons (14, 39). Our observation that MPS is not abundant in two-DIV axons does not rule out the function of a nonperiodic membrane-associated spectrin-actin network. Both βII spectrin and actin are distributed along the axonal cortex and are likely to influence the mechanical properties of axons even in early stages. The prominent organization of actin in periodic rings in older neurites raises the question of how such structures may support axial contractility. This question will have to be systematically investigated in the future, especially in light of recent results showing that in older neurons, pMLC colocalizes with actin rings in the axon initial segment while being conspicuously absent from the distal axon (38).

In summary, although these data do not identify a specific actomyosin organization contributing to axial contractility, they suggest that in two-DIV chick DRG, a diffuse network of cortical actomyosin organization may regulate contractility along the length of the axon (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Model for cytoskeletal mechanisms mediating axonal straightening. In two-DIV chick DRG neurons, the cortical actomyosin network contracts upon detachment induced by unknown feedback mechanisms, leading to the straightening of axons. The actomyosin network appears to be distributed along the length of the axon and is capable of local remodeling (indicated by pairs of arrows). At this stage, axons show a weakly periodic actin-spectrin MPS sparsely distributed along the axon length. This has not been included in the schematic. Microtubule sliding and rearrangement are likely to be necessary to accommodate the contraction. To see this figure in color, go online.

As the axonal length shortens, it is expected that microtubule sliding will be necessary to accommodate this change (Fig. 7). Thus, future investigations into the function of microtubule sliding and cross-linking activities are also likely to reveal important mechanistic modalities.

In a complex environment, turning and pausing of growth cones might impart curvature along axons. Branch dynamics and competition between the branches can also lead to the curved morphology of axons. During neurite outgrowth, the growth cone translocation results in pulling forces that are balanced by the neurite tension. It has been suggested that modulation of this force balance may influence growth-cone turning (40). In addition to growth-cone-mediated straightening (41), passive stretch from surrounding tissue can also contribute to axonal tension (42). In our experiments, straightening on patterned substrates suggests that although axons may follow curved trajectories because of the directional biases of the growth cone, the axonal contractile forces are able to spontaneously develop and straighten axonal segments between two points of strong adhesion. This occurs without towing by the growth cone and points to axon-intrinsic contractility as the major regulator of axonal tension and, in turn, axon conformation. Though currently unknown, it is possible that the adhesive sites may initiate mechanochemical feedback responses that enhance axonal contractility. We propose spontaneous actomyosin-driven axonal contractility as a local mechanism for maintaining the rest tension, which is known to influence various neurodevelopmental processes, including length minimization at the level of the network.

Author Contributions

S.P.M., P.A.P., J.J., and A.G. designed the research and analysis. S.P.M. performed the research and analyzed the data. S.P.M., P.A.P., J.J., and A.G. wrote the manuscript. A.G. secured funding. All authors read and reviewed the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Richa Rikhy, IISER Pune, is acknowledged for providing MitoTracker Green FM. Dr. Deepak Barua, IISER Pune, is acknowledged for advice regarding statistical analysis. The authors thank Prof. N. K. Subhedar for critical reading of the manuscript.

The authors acknowledge intramural funding from IISER Pune and an infrastructural Nano Mission Council, Department of Science and Technology (SR/NM/NS-42/2009) grant to IISER Pune. The IISER Pune Microscopy facility is gratefully acknowledged for access to microscopes.

Editor: Laurent Blanchoin.

Footnotes

Supporting Materials and Methods, ten figures, and two videos are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(18)30776-8.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.O’Toole M., Lamoureux P., Miller K.E. A physical model of axonal elongation: force, viscosity, and adhesions govern the mode of outgrowth. Biophys. J. 2008;94:2610–2620. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.117424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dennerll T.J., Lamoureux P., Heidemann S.R. The cytomechanics of axonal elongation and retraction. J. Cell Biol. 1989;109:3073–3083. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.6.3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franze K., Gerdelmann J., Käs J. Neurite branch retraction is caused by a threshold-dependent mechanical impact. Biophys. J. 2009;97:1883–1890. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed W.W., Saif T.A. Active transport of vesicles in neurons is modulated by mechanical tension. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:4481. doi: 10.1038/srep04481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siechen S., Yang S., Saif T. Mechanical tension contributes to clustering of neurotransmitter vesicles at presynaptic terminals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:12611–12616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901867106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen B.M., Grinnell A.D. Kinetics, Ca2+ dependence, and biophysical properties of integrin-mediated mechanical modulation of transmitter release from frog motor nerve terminals. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:904–916. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-03-00904.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fan A., Stebbings K.A., Saif T. Stretch induced hyperexcitability of mice callosal pathway. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015;9:292. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anava S., Greenbaum A., Ayali A. The regulative role of neurite mechanical tension in network development. Biophys. J. 2009;96:1661–1670. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.10.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hilgetag C.C., Barbas H. Role of mechanical factors in the morphology of the primate cerebral cortex. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2006;2:e22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mukhopadhyay R., Kumar S., Hoh J.H. Molecular mechanisms for organizing the neuronal cytoskeleton. BioEssays. 2004;26:1017–1025. doi: 10.1002/bies.20088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kevenaar J.T., Hoogenraad C.C. The axonal cytoskeleton: from organization to function. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2015;8:44. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2015.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He J., Zhou R., Zhuang X. Prevalent presence of periodic actin-spectrin-based membrane skeleton in a broad range of neuronal cell types and animal species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:6029–6034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605707113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu K., Zhong G., Zhuang X. Actin, spectrin, and associated proteins form a periodic cytoskeletal structure in axons. Science. 2013;339:452–456. doi: 10.1126/science.1232251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krieg M., Stühmer J., Goodman M.B. Genetic defects in β-spectrin and tau sensitize C. elegans axons to movement-induced damage via torque-tension coupling. eLife. 2017;6:e20172. doi: 10.7554/eLife.20172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ganguly A., Tang Y., Roy S. A dynamic formin-dependent deep F-actin network in axons. J. Cell Biol. 2015;210:401–417. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201506110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.George E.B., Schneider B.F., Katz M.J. Axonal shortening and the mechanisms of axonal motility. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 1988;9:48–59. doi: 10.1002/cm.970090106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajagopalan J., Tofangchi A., A Saif M.T. Drosophila neurons actively regulate axonal tension in vivo. Biophys. J. 2010;99:3208–3215. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernal R., Pullarkat P.A., Melo F. Mechanical properties of axons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007;99:018301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.018301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallo G. Myosin II activity is required for severing-induced axon retraction in vitro. Exp. Neurol. 2004;189:112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joshi H.C., Chu D., Heidemann S.R. Tension and compression in the cytoskeleton of PC 12 neurites. J. Cell Biol. 1985;101:697–705. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.3.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tofangchi A., Fan A., Saif M.T.A. Mechanism of axonal contractility in embryonic drosophila motor neurons in vivo. Biophys. J. 2016;111:1519–1527. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spira M.E., Oren R., Lev S. Calcium, protease activation, and cytoskeleton remodeling underlie growth cone formation and neuronal regeneration. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2001;21:591–604. doi: 10.1023/a:1015135617557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gitler D., Spira M.E. Real time imaging of calcium-induced localized proteolytic activity after axotomy and its relation to growth cone formation. Neuron. 1998;20:1123–1135. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80494-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernal R., Melo F., Pullarkat P.A. Drag force as a tool to test the active mechanical response of PC12 neurites. Biophys. J. 2010;98:515–523. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ludueña M.A. The growth of spinal ganglion neurons in serum-free medium. Dev. Biol. 1973;33:470–476. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(73)90152-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Théry M., Piel M. Adhesive micropatterns for cells: a microcontact printing protocol. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2009;2009(7) doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5255. prot5255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmad F.J., Hughey J., Baas P.W. Motor proteins regulate force interactions between microtubules and microfilaments in the axon. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:276–280. doi: 10.1038/35010544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang-Schomer M.D., Patel A.R., Smith D.H. Mechanical breaking of microtubules in axons during dynamic stretch injury underlies delayed elasticity, microtubule disassembly, and axon degeneration. FASEB J. 2010;24:1401–1410. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-142844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He Y., Yu W., Baas P.W. Microtubule reconfiguration during axonal retraction induced by nitric oxide. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:5982–5991. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-14-05982.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boldogh I.R., Pon L.A. Interactions of mitochondria with the actin cytoskeleton. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1763:450–462. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kang J.S., Tian J.H., Sheng Z.H. Docking of axonal mitochondria by syntaphilin controls their mobility and affects short-term facilitation. Cell. 2008;132:137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wagner O.I., Lifshitz J., Leterrier J.F. Mechanisms of mitochondria-neurofilament interactions. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:9046–9058. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-27-09046.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chetta J., Kye C., Shah S.B. Cytoskeletal dynamics in response to tensile loading of mammalian axons. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2010;67:650–665. doi: 10.1002/cm.20478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller K.E., Sheetz M.P. Direct evidence for coherent low velocity axonal transport of mitochondria. J. Cell Biol. 2006;173:373–381. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katz M.J. How straight do axons grow? J. Neurosci. 1985;5:589–595. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-03-00589.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.D’Este E., Kamin D., Hell S.W. STED nanoscopy reveals the ubiquity of subcortical cytoskeleton periodicity in living neurons. Cell Reports. 2015;10:1246–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhong G., He J., Zhuang X. Developmental mechanism of the periodic membrane skeleton in axons. eLife. 2014;3:e04581. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berger S.L., Leo-Macias A., Salzer J.L. Localized myosin II activity regulates assembly and plasticity of the axon initial segment. Neuron. 2018;97:555–570.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krieg M., Dunn A.R., Goodman M.B. Mechanical control of the sense of touch by β-spectrin. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014;16:224–233. doi: 10.1038/ncb2915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hyland C., Mertz A.F., Dufresne E. Dynamic peripheral traction forces balance stable neurite tension in regenerating Aplysia bag cell neurons. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:4961. doi: 10.1038/srep04961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bray D. Axonal growth in response to experimentally applied mechanical tension. Dev. Biol. 1984;102:379–389. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(84)90202-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harrison R.G. The croonian lecture on the origin and development of the nervous system studied by the methods of experimental embryology. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1935;118:155–196. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This video shows footage of axonal straightening after trypsin-mediated deadhesion.

This video shows footage of spontaneous axonal contraction.