Abstract

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) of liver is extremely rare hepatic neoplasm with only 30 cases reported in the literature. These lesions are found mainly in young females and may present a potential pitfall in the characterisation of focal liver lesions. The biological behavior of PEComa varies from generally benign to rarely malignant and metastatic disease. We report a case of a patient with hepatic PEComa with the corresponding imaging findings on the ultrasound, contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) and hepatospecific MRI. After failed attempt to characterize the lesion by percutaneous biopsy, surgical resection was conducted and the final diagnosis was achieved.

Keywords: Perivascular epithelioid tumor, PECOM, Focal liver lesion, CEUS, MRI

1. Introduction

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) is a mesenchymal neoplasm, predominantly affecting young female adults. The predominant site of origin for PEComa is a uterus, but the tumor may be found in various locations in the body. Cases in the liver are extremely rare [1] and up to this date, only 30 cases of liver PEComas were reported in the literature and only two of them included imaging findings on contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS). The biological behavior of PEComa varies in different cases from generally benign to rarely malignant and metastatic disease [2].

2. Case report

A 24 - year old previously healthy female was referred to a gastroenterologist for unspecific pain in the lower abdominal region. The physical examination was normal and the levels of laboratory tests were within reference ranges. An ultrasound examination of the abdomen revealed normal sized liver with normal echotexture of liver parenchyma. A well-defined 20 mm hypoechogenic lesion with mass effect was identified in the segment IV of the liver. Colour Doppler analysis demonstrated hyperemia in the lesion in comparison with normal hepatic tissue (Fig. 1). No pathologic lymph nodes or other pathologic findings were noted at the examination. CEUS was performed for characterization of the liver lesion. A 1.8 ml of second-generation ultrasound contrast media SonoVue (Bracco, Italy) was used for the examination. The lesion showed homogenous hyperechogenic enhancement in the arterial phase (20–40 s post injection) (Fig. 2) and stayed iso- to hyperechogenic in comparison to surrounding liver parenchyma in portal venous (60–120 s post injection) and late phase (2–4 min post injection). On the basis of enhancement pattern and absence of diffuse liver disease, the differential diagnosis of focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) or hepatic adenoma was made according to EFSUMB Guidelines for Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound in the Liver [3]. The patient was scheduled for US follow-up exam. This was performed after six months and it revealed an increase in the size of the lesion (25 mm) with the same pattern of enhancement. The growth of the lesion was the indication for the referral of the patient to the MRI examination of the liver.

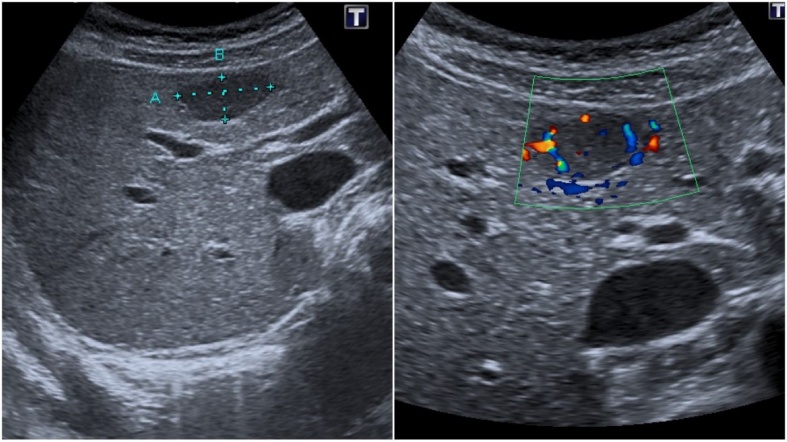

Fig. 1.

Ultrasound examination of the abdomen revealing well-defined, hypoechogenic incidental lession in the liver (a). Color dopler analysis demonstrates a hypervascularity of the lession (b).

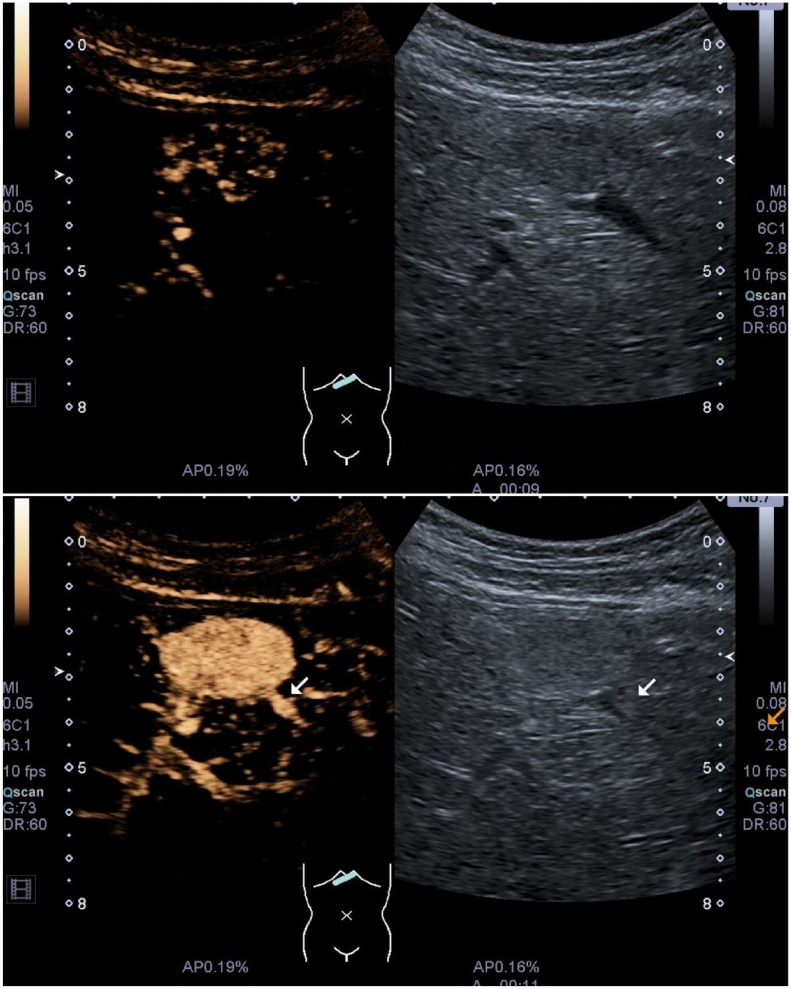

Fig. 2.

Contrast enhanced ultrasound examination showing a homogeneous enhancing vascular lesion in arterial phase - 9 s (a) and 11 s (b) after the injection of contrast media.

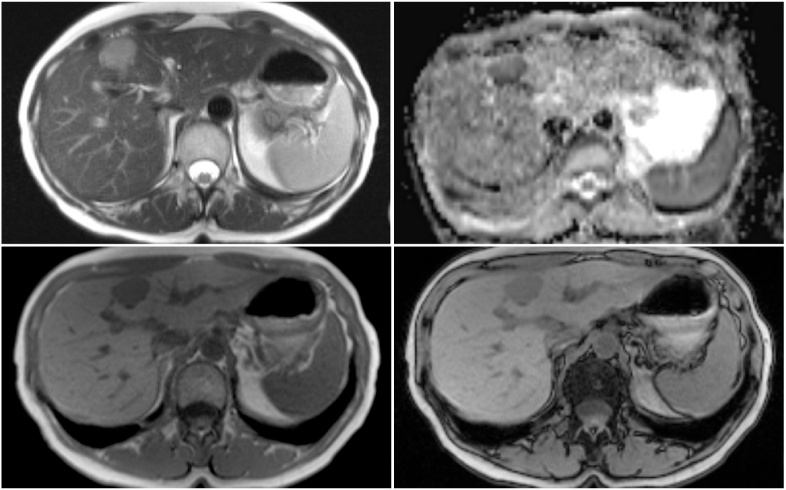

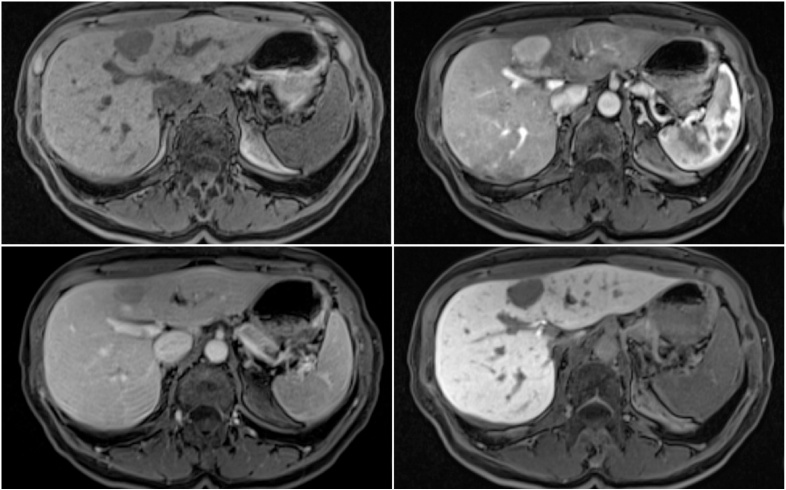

MRI with the hepatobiliary-specific contrast agent demonstrated a 25 mm liver lesion that was hypointense on T1 and hyperintense on T2 weighted sequences and showed no notable signal drop on GRE opposed-phase sequences (Fig. 3). After the injection of the contrast medium lesion demonstrated a homogeneous hyperintense enhancement in the arterial phase and washout was noted in portal venous phase (70 s post injection) and in the late phase (2 min post injection). The lesion was completely hypointense in hepatospecific phase (Fig. 4), a feature not specific for FNH and ultrasound guided histologic puncture was subsequently indicated. The result of histologic puncture was inconclusive and the decision for surgical treatments was made.

Fig. 3.

MRI shows a well-defined lesion in liver segment IV. Lesion is moderately hyperintense on T2 HASTE sequence (a) and shows restriction of diffusion (b). In-phase GRE (c) and out-of-phase GRE (d) sequences were performed and no drop of signal was noted in the lesion.

Fig. 4.

MRI of the liver with hepatobiliary-specific contrast agent. (a) Lesion is hypointense on T1 VIBE pre-contrast mage. (b) Lesion shows intense homogeneous enhancement in the arterial phase. (c) Lesion is hypointense in comparison with liver parenchyma in venous and in hepatospecific phase (d).

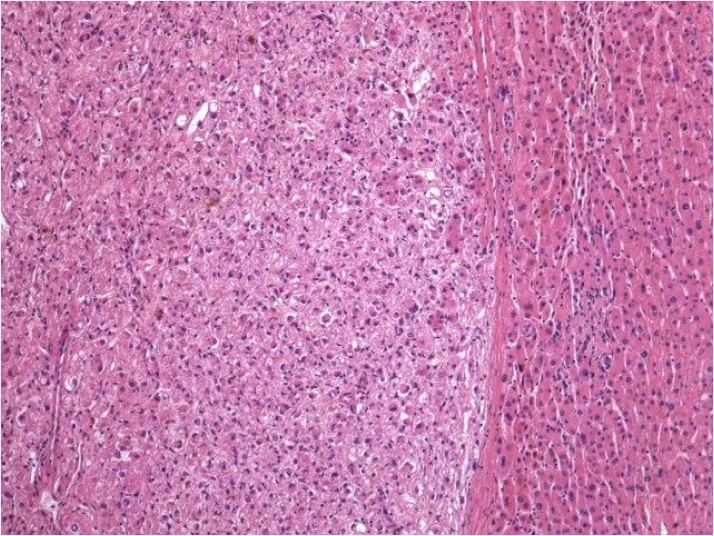

Non-anatomical resection achieved complete resection of the tumor and histological examination revealed a well-demarcated and unencapsulated tumor with epithelioid cells growing in sheets and displaying perivascular arrangements. The nuclei of tumor cells were bland with occasional regular mitoses (Fig. 5). By immunohistochemistry, tumor cells were diffusely positive for HMB45 and melan A, focally positive for smooth muscle actin and S100, and were negative for desmin. The histological features and the results of immunohistochemical stainings were consistent with PEComa of the liver.

Fig. 5.

Well-demarcated and unencapsulated proliferation of neoplastic epithelioid cells in the liver. Hematoxylin and eosin, magnification 100×.

3. Discussion

The term of perivascular epithelioid cell unifies a class of tumors that share the presence of smooth muscle and melanocytic differentiation. PEComas have been described in different organs such as the liver, uterus, vulva, rectum, heart, breast, urinary bladder, abdominal wall and are considered ubiquitous tumors. Clinical presentation of liver PEComas are unspecific and a definite pre-operative diagnosis is difficult to make due to non-specific radiological features. It might be often misdiagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma, hemangioma, FNH and GIST tumor [4]. The first reported case of hepatic PEComa was in 2000 by Yamasaki [5]. We have performed a literature search using MEDLINE and found altogether 30 cases of hepatic PEComas to this date and only two cases of PEComas where the CEUS imaging was performed.

Tumors were usually found in healthy livers and the right lobe of the liver was the most common site. Size varied from 0.8 to 23 cm in greatest dimension (mean 8 cm). The usual ultrasonographic appearance was described as a well-defined round lesion that can be of any echogenicity at B-mode ultrasound and with a hypervascular appearance at color Doppler imaging [6].

In our case, CEUS was performed following B-mode ultrasound for lesion characterisation. There are only two case reports of PEComa studied with CEUS by Della Vigna and Akitake [7,8]. SonoVue was used as a contrast reagents by Della Vigna and Sonazoid was used by Akitake [7,8]. In both cases tumors showed same enhancement pattern as in our case - homogeneous hyperenhancement on the arterial phase, isoechogenicity on the portal vein phase, and iso- to hyperechogenicity on the late phase. In non-cirrhotic liver, this pattern of enhancement is considered diagnostic for FNH or adenoma according to EFSUMB guidelines and it can cause misdiagnosis. This pitfall in diagnosis was observed in our case an also in the case published by Della Vigna [3,7].

The MRI of the liver with hepatospecific contrast agent gadolinium-ethoxybenzyl-DTPA (GD-EOB-DTPA) was performed because of the growth of the lesion. GD-EOB-DTPA is magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent distributes into the hepatocytes and bile ducts during the hepatobiliary phase, therefore indicating hepatocytes containing lesions. Our tumor showed hyperenhancement in arterial phase, but was completely hypointense in the hepatospecific phase the, indicating lack of hepatobiliary function and ruling-out the diagnosis of FNH.

The diagnosis of PEComa was made based on histological examination of the tumor and subsequent additional immunohistochemical examination. The majority of reported cases presented benign tumors but some PEComas can show malignant potential with local recurrences and distant metastasis [9]. There is no particular treatment protocol for hepatic PEComas. Most tumors were surgically treated with good results. Only in one case of malignant hepatic PEComa sirolimus was used as neoadjuvant chemotherapy agent [10].

4. Conclusion

Hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumor is a rare hepatic neoplasm and may represent a potential pitfall in characterisation of an incidentally discovered liver lesion. In our case the characterization with contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) was performed, and an arterialized liver lesion was initially mistakenly characterized as FNH or adenoma by using the EFSUMB Guidelines for Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound in the Liver [3]. Later growth of the tumor, MRI and histologic examination were used for appropriately diagnosing tumor as hepatic PEComa. Since CEUS has established its position in Europe and is gaining popularity in USA, learning potential pitfalls is necessary for successful implementation of this imaging modality into practice.

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors of the article certify that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Liu D., Shi D., Xu Y., Cao L. Management of perivascular epithelioid cell tumor of the liver: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol. Lett. 2014;7(1):148–152. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martignoni G., Pea M., Reghellin D., Zamboni G., Bonetti F. PEComas: the past, the present and the future. Virchows Arch. 2008;452(2):119–132. doi: 10.1007/s00428-007-0509-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Claudon M., Dietrich C.F., Choi B.I. Guidelines and good clinical practice recommendations for contrast enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in the liver--update 2012: a WFUMB-EFSUMB initiative in cooperation with representatives of AFSUMB, AIUM, ASUM, FLAUS and ICUS. Ultraschall Med. 2013;34(1):11–29. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1325499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Genevay M., Mc Kee T., Zimmer G., Cathomas G., Guillou L. Digestive PEComas: a solution when the diagnosis fails to “fit”. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2004;8(6):367–372. doi: 10.1053/j.anndiagpath.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamasaki S., Tanaka S., Fujii H. Monotypic epithelioid angiomyolipoma of the liver. Histopathology. 2000;36(5):451–456. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan Y., Xiao E. Hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa): dynamic CT, MRI, ultrasonography, and pathologic features--analysis of 7 cases and review of the literature. Abdom. Imaging. 2012;37(5):781–787. doi: 10.1007/s00261-012-9850-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vigna P., Della, Preda L., Della, Vigna P. Growing perivascular epithelioid cell tumor of the liver studied with contrast-enhanced ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging. J. Ultrasound Med. 2008;27(12):1781–1785. doi: 10.7863/jum.2008.27.12.1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akitake R., Kimura H., Sekoguchi S. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) of the liver diagnosed by contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. Intern. Med. 2009;48(24):2083–2086. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Folpe A.L., Kwiatkowski D.J. Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms: pathology and pathogenesis. Hum. Pathol. 2010;41(1):1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergamo F., Maruzzo M., Basso U. Neoadjuvant sirolimus for a large hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) World J. Surg. Oncol. 2014;12:46. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]