Abstract

Introduction:

Periodontal diseases are caused by pathogenic bacteria locally colonized in the dental biofilm creating infection; the main etiological factor is represented by dental plaque and in particular by anaerobic Gram-negative bacilli. For that reason, the first phase of periodontal treatment is always represented by the initial preparation which primarily aims at the elimination or reduction of bacterial infection and the control of periodontal plaque-associated inflammation. Yet, another innovative causal therapy is represented by the irradiation of periodontal pockets with LASER. The aim of this randomized clinical study is to compare and to detect the presence of periodontal pathogens in chronic periodontitis patients after nonsurgical periodontal therapy with and without diode LASER disinfection using BANA test.

Materials and Methods:

This randomized clinical trial includes 20 patients having chronic periodontitis. From each patient, one test site and one control site were selected and assessed for gingival index (GI), oral hygiene index (OHI), pocket probing depth and clinical attachment level (CAL), and presence of BANA pathogens. The test site underwent scaling and root planning along with diode LASER therapy as an adjuvant while the control site received scaling and root planning alone. Patients were recalled for review after 2 weeks and 2 months where periodontal parameters were assessed and plaque samples were collected and analyzed for BANA pathogens.

Results:

The test site where LASER was used as an adjuvant showed significant reduction in pocket probing depth, CAL, OHI, GI, and periodontal pathogens which shows that the amount of recolonization of microbes is less when LASER is used as an adjuvant to conventional therapy.

Conclusion:

Diode LASER as an adjuvant to SRP has shown additional benefits over conventional therapy in all the clinical parameters evaluated and this can be associated in the treatment of periodontal therapy. BANA-enzymatic kit is a simple chair side kit which can be reliable indicator of BANA positive species in dental plaque.

Keywords: Benzoyl–DL arginine-2-naphthylamide, chronic periodontitis, laser, red complex

Introduction

Periodontitis is characterized by gingival inflammation and often results in periodontal pocket formation with loss of the supporting alveolar bone and connective tissue around the teeth. Various etiological factors which cause periodontitis include local and systemic factors.[1]

Periodontal therapy aims at the regeneration of the periodontal tissues, i.e. the restoration of their initial form, architecture, and function. It includes conventional methods such as scaling and root planing, periodontal surgery with or without osseous surgery, root conditioning agents, guided tissue regeneration, the use of different grafting materials, and their combination.[2] However, it has limitations such as the long-term maintainability of deep periodontal pockets and the risk of disease recurrence.

Recent studies have shown that the use of LASER has been reported as an alternative therapy for root surface debridement. Diode LASER commonly used for pocket disinfection is known for its bactericidal effectiveness. It is very effective for soft-tissue application and for the removal of smear layer. Studies have shown that the combination of SRP and LASER shows more effective decontamination of pocket along with significant improvement in attachment gain and reduction in pocket probing depth with less recolonization of bacteria in treated sites.[3]

Many paraclinical methods are available today for accurate assessment of periodontal status prior and during periodontal therapy. The microbial-enzymatic N – benzoyl–DL arginine-2-naphthylamide (BANA) test is one of the modern alternatives to bacterial cultures. It detects the presence of three key periodontal pathogens for anaerobic periodontal infections (Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticola, and Tannerella forsythia).[4] In comparison to other tests, BANA test seemed to be accurate as it exhibits high accuracy, high sensitivity, and culture accuracy. In addition, through this chair-side test, we can predict the probability of periodontal disease in the near future.

The purpose of this study is to detect and compare the presence of periodontal pathogens in chronic periodontitis patients after nonsurgical periodontal therapy with and without diode LASER disinfection using BANA test.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This was a randomized, clinical trial.

Study settings and study participants

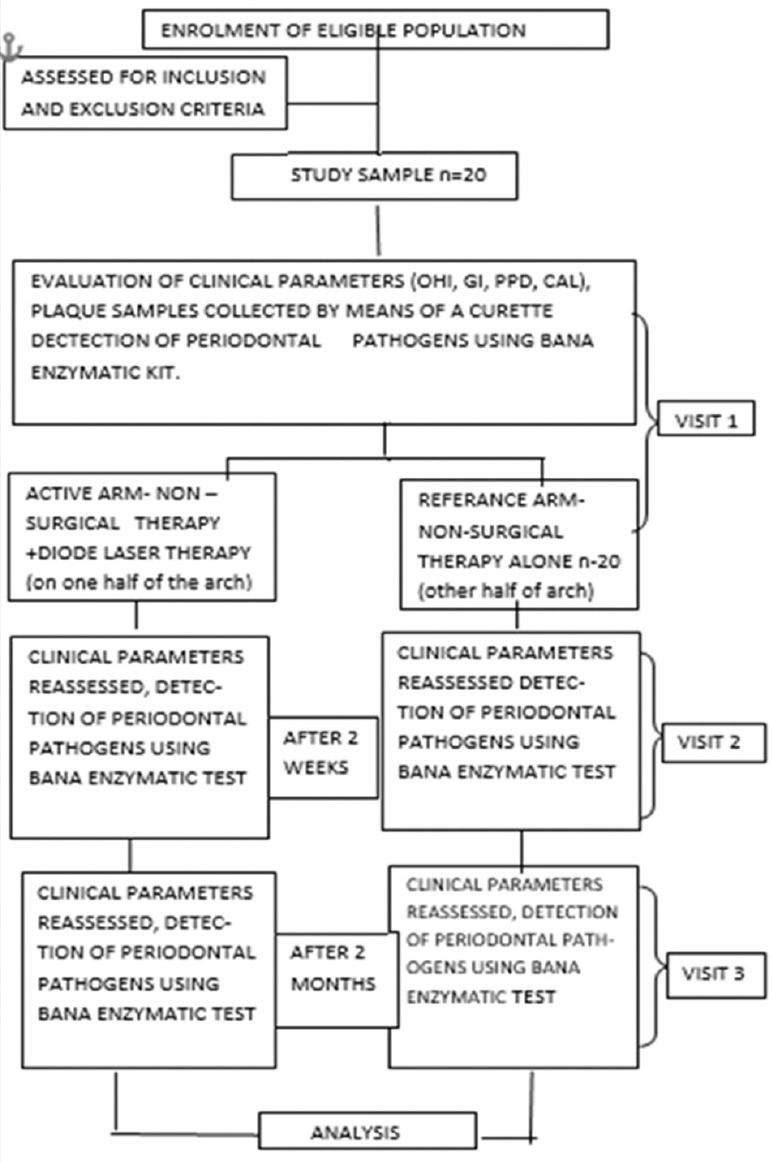

This study was conducted in the outpatient section of the Department of Periodontology at Amrita School of dentistry Kochi. This study is registered under the clinical trial registry of India, and the trail registration no is CTRI/2017/11/010490. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethical Committee of Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Kochi, and Kerala, India. In the present study, 60 participants who were between 30 and 60 years of age and who matched the inclusion and exclusion criteria were randomly selected from the Department of Periodontology. A total of 20 patients who matched the pocket depth of > 6 mm and a positive BANA test were selected for the study. The site allocation as either test or control was determined using coin toss method [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Consort chart for randomized clinical trial

Criteria for selection

Inclusion criteria

Age group of patients 30–60 years

Participants s with moderate-severe periodontitis with clinical attachment loss of >6 mm at 5 or more sites

Having no systemic disease

No periodontal therapy other than standard prophylaxis during the previous 6 months.

Exclusion criteria

Any bacterial infection

Diabetes mellitus

Pregnant women/lactating mother

Patients who were on antibiotic prophylaxis

Those who regularly use nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication

Patients who smoke or chew any form of tobacco.

Method

Data were collected at baseline (before therapy), 2 weeks, and 2 months (after therapy). In each participant, periodontal pockets were assessed on all 6 sites of the molars except the 3rd molars. A total of 20 participant who matched the pocket probing depth ≥6 mm and a positive BANA test were selected for the study. Plaque samples were collected from the test and control site by the means of a sterile curette and assessed for the presence of periodontal pathogens using BANA enzymatic kit.

Sample collection and preparation

Remove a BANA test strip from the bottle just prior to use. The BANA-enzyme test reagents are sensitive to light and humidity, so that only the strip to be used should be removed from the bottle, and the bottle cap should be replaced and tightened. Record the patients name and date in the spaces provided.

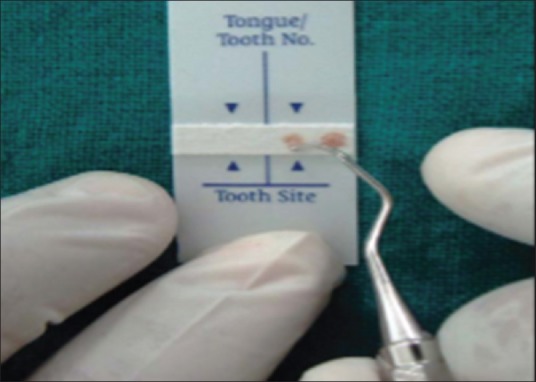

Remove supragingival plaque before sampling. Apply the subgingival plaque specimens using a curette onto the raised reagent matrix affixed to the lower portion of the test strip. Before taking another specimen, wipe the curette on a clean piece of cotton or other suitable wipe to prevent carry-over of plaque [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Collection of sample

After all, desired sites have been sampled, moisten the upper test strip (Salmon color) with distilled water using a cotton swab.

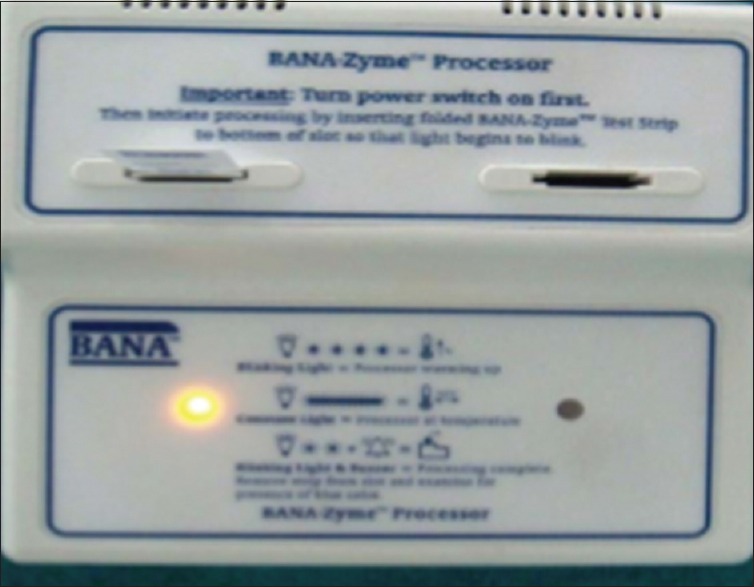

Fold BANA-enzyme test strip at the crease mark so that the lower and upper reagent strips meet with each other Place the BANA-Zyme test strip into either of the slots on the top of the processor.

The heating element of the processor will start automatically when the strip is inserted to the bottom of the slot, as indicated by the flashing light. The flashing light turns off when the heating element has reached 55°C and will stay on for 5 min [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Incubation for 15 min for 55°C

Remove the BANA-enzyme test from the processor and discard the lower reagent strip that had been inoculated with plaque in a manner appropriate for contaminated material.

Examine the upper reagent strip for the presence of any blue color. If a blue color is detected, mark the site as either negative or positive.

The change from colorless to blue indicated the presence of periodontal pathogens. After which, the site allocation was done as either test or control sites using coin toss method.

The test site underwent scaling and root planing along with diode LASER therapy as an adjuvant. The power setting was 0.84 W, wavelength 980 nm, energy level 0.80J/s, and mode of beam delivery as a continuous pulse. A new tip was initiated before each patient. The LASER fiber was inserted toward the bottom of pocket in a noncontacting mode. The LASER tip was moved apically and horizontal sweeping mode. The control site received scaling and root planing alone. Patients were recalled for review after 2 weeks and 2 months when periodontal parameters were assessed and plaque samples were collected and analyzed.

Measurements were taken 7 days after baseline and 1 week prior 2 months measurements, periodontal examinations of 10 participants were repeated showing intraexaminer reproducibility score higher than 0.85 (kappa test) for probing pocket depth (PPD) and clinical attachment level (CAL).

Statistical analysis

Statistical tests were performed using the software Statistical Package for Social Sciences, IBM version 21, Chicago, USA. For all continuous variable, the results are either given in mean ± standard deviation and for categorical variables as percentage. To compare the mean difference of the numerical variable within group, paired t-test was applied. To find out the efficacy of both methods, mcnemar test was used. P = 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

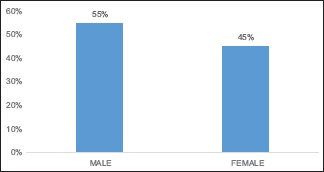

The study was conducted on 20 participants who were between 30 and 60 years of age and matched the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The mean age of the participants in the study group is 47.05 ± 5.6. Among the participants, 11 were males and 9 were females [Table 1 and Graph 1].

Table 1.

Frequency distribution of gender

Graph 1.

Frequency distribution of gender

Parameters such as oral hygiene index (OHI), gingival index (GI), CAL, and PPD were measured at baseline for both groups before the periodontal therapy and the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant stating that the baseline parameters were homogenous.

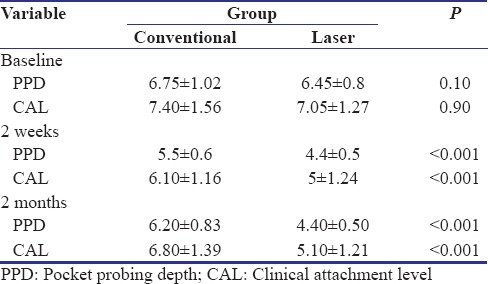

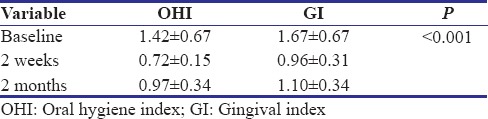

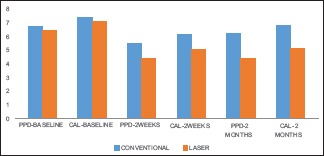

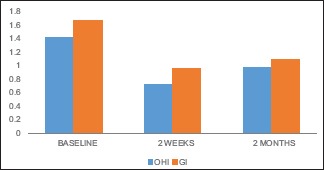

PPD, CAL OHI, and GI showed a statistically significant difference from baseline to 2 weeks (P < 0.001) and from baseline to 2 months in both the test and control group suggestive of the fact that both conventional and LASER as an adjuvant therapy were effective (P < 0.001) [Tables 2, 3 and Graphs 2, 3].

Table 2.

Comparision of periodontal parameters at baseline, 2 weeks, 2 months between conventional therapy and laser

Table 3.

Comparision of OHI and GI at baseline, 2 weeks, 2 months

Graph 2.

Comparision of periodontal parameters at baseline, 2 weeks, 2 months between conventional therapy and laser

Graph 3.

Comparision of OHI and GI at baseline, 2 weeks, 2 months

Intergroup comparison of the OHI, GI, PPD, and CAL after treatment have shown a statistically significant reduction in the test group compared to control group both at 2 weeks and 2 months. This shows that LASER when used as an adjuvant to SRP is more effective in reducing the OHI, GI, PPD, and CAL than when using SRP alone [Tables 2, 3 and Graphs 2, 3].

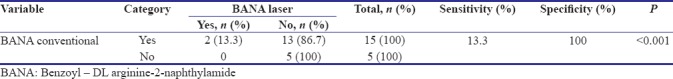

In our present study, microbial analysis was done using BANA nonenzymatic test to compare and to detect the presence of periodontal pathogens in chronic periodontitis patients to evaluate the efficacy of LASER being an adjuvant to periodontal therapy. The result showed that there was a reduction of the key pathogens in both test an control group at end of 2 weeks but at the end of 2 months the test group showed more statistical significant (P < 0.001) reduction on key pathogens (using BANA test) when comparing to traditional conventional group [Table 4 and Graph 4].

Table 4.

Comparision of BANA at 2 months between conventional therapy and adjuvant laser therapy

Graph 4.

comparision of bana at 2 months between conventional therapy and adjuvant laser therapy

Discussion

Periodontal diseases are caused by pathogenic bacteria (in particular by anaerobic Gram-negative bacilli) locally colonized in the dental biofilm creating infection and subsequent inflammatory response in the supporting structures of the teeth. For that reason, the first phase of periodontal treatment primarily aims at the elimination or reduction of bacterial infection and the control of periodontal plaque-associated inflammation. The use of LASER therapy, as shown by several studies, appears to improve and facilitate the healing of irradiated pocket sites.

The purpose of this study was to detect and to compare the presence of periodontal pathogens using BANA test in chronic periodontitis patients after nonsurgical periodontal therapy with and without diode LASER disinfection. Thus, the efficacy of LASER was analyzed when it was used as an adjuvant to nonsurgical periodontal therapy. The periodontal parameters were assessed at baseline, 2 weeks, and 2 months.

The study was conducted on 20 participants who were between 30 and 60 years of age and matched the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

PPD, CAL, OHI, and GI showed a statistically significant difference from baseline to 2 weeks (P < 0.001) and from baseline to 2 months (P < 0.001) suggestive of the fact that both conventional and LASER as an adjuvant therapy were effective [Tables 2, 3 and Graphs 2, 3].

The parameters assessed here and their correlation with the finding is similar to several studies by Haffajee et al. at 1997[5] which concluded that root debridement resulted in clinical improvements, such as reduction in periodontal pocket probing depth, CAL, bleeding on probing sites, and reduced levels of subgingival bacteria.

Intergroup comparison of the PPD, and CAL after treatment has shown a statistically significant reduction in test group compared to the control group both at 2 weeks and 2 months. This shows that LASER when used as an adjuvant to SRP is more effective in reducing the PPD and CAL than when using SRP alone [Table 3 and Graph 3].

This remarkable difference between the two procedures in improving periodontal variables is attributable to the benefits from the use of diode LASER in addition to the traditional procedure of SRP is due to the:

Bactericidal effect

Curettage effect

Biostimulating effect.

The wavelength of the diode LASER is absorbed by protohemin and protoporphyrin IX pigments of the pigmented anaerobic periopathogens which lead to the vaporization of water and causes lysis of the cell wall of the bacteria, leading to bacterial cell death.

On a cellular level, due to biostimulation caused by diode LASER, metabolism is increased. This causes increase in the production of adenosine triphosphate, the fuel that powers the cell. This increase in energy is available to normalize cell function and promote tissue healing. Its role in wound healing has also been enumerated to hemostasis and coagulation which eventually results in a better periodontal health.[6]

The result of the study is accordance with a study by Crispino et al. at in 2015[7] where a study was conducted to evaluate the effect of a 940-nm diode LASER as an adjunct to SRP in patients affected by periodontitis where it showed statistically significant improvements in PD, SBI, GI, and CAL with less discomfort and treatment time.

Contrary to our, study by De Micheli et al. 2011,[8] Dukić et al. 2013[9] concluded that the results of the two therapeutic procedures are similar with regard to plaque index and bleeding on probing, for which LASER therapy does not provide additional benefits.

The microbial-enzymatic N–BANA test is one of the modern alternatives to bacterial cultures which detects the presence of three key periodontal pathogens for anaerobic periodontal infections (P. gingivalis, T. denticola, and T. forsythia.

Loesche et al. at 1990,[10] described that the BANA test seemed to be accurate as it exhibits high accuracy, high sensitivity, and culture accuracy when in comparison with the DNA probes, and an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or an indirect immunofluorescence assay for the detection of P. gingivalis, T. denticola, and B. forsythus.

Dhalla, et al. in 2015[11] conducted a study to detect the presence of BANA microorganisms and also to determine the effect of scaling and root planing in adult periodontitis patients. The results showed that the BANA non-enzymatic chair-side tests can be used for a proper diagnosis of periodontal disease and for a good evaluation of the treatment results.

In our present study, microbial analysis was done using BANA non-enzymatic test to compare and to detect the presence of periodontal pathogens in chronic periodontitis patients to evaluate the efficacy of LASER being an adjuvant to periodontal therapy. The result showed that there was a reduction of the key pathogens in both test an control group at end of 2 weeks but at the end of 2 months the test group showed more statistical significant (P < 0.001) reduction on key pathogens (using BANA test) when comparing to traditional conventional group. This shows that there was less recolonization when LASER is used as an adjuvant, which is consistent with the results obtained in several other studies [Table 4 and Graph 4].

Our results are in accordance with study by Kamma et al. 2009[12] Moritz et al. 1997[13] which showed that combining mechanical treatment (SRP) with diode LASER therapy produces better results than the LASER therapy alone, both in clinical (probing depth and CAL) and bacteriological terms total bacterial count of periodontal pathogens.

Limitation

BANA is a qualitative test which detects the presence of certain periopathogens but fails to quantify the same. A small sample size is also another limitation of the study. A large sample size would have been more reflective of the parameter investigated in our study. Hence, further research may help to overcome these limitations.

Conclusion

From the observation of the study, the following conclusion was drawn suggesting that diode LASER has shown additional benefits over conventional therapy in all the clinical parameters evaluated, and this can be routinely associated with SRP in the treatment of periodontal pockets. BANA-enzymatic kit may be a simple chair side kit which can be reliable indicator of BANA positive species in dental plaque.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Tonetti MS, Pini-Prato G, Cortellini P. Periodontal regeneration of human intrabony defects. IV. Determinants of healing response. J Periodontol. 1993;64:934–40. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.10.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pick RM, Pecaro BC, Silberman CJ. The laser gingivectomy. The use of the CO2 laser for the removal of phenytoin hyperplasia. J Periodontol. 1985;56:492–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.8.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris DM, Yessik M. Therapeutic ratio quantifies laser antisepsis: Ablation of Porphyromonas gingivalis with dental lasers. Lasers Surg Med. 2004;35:206–13. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haraszthy VI, Zambon JJ, Trevisan M, Zeid M, Genco RJ. Identification of periodontal pathogens in atheromatous plaques. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1554–60. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.10.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haffajee AD, Cugini MA, Dibart S, Smith C, Kent RL, Jr, Socransky SS, et al. The effect of SRP on the clinical and microbiological parameters of periodontal diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:324–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb00765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qadri T, Tunér J, Gustafsson A. Significance of scaling and root planing with and without adjunctive use of a water-cooled pulsed Nd: YAG laser for the treatment of periodontal inflammation. Lasers Med Sci. 2015;30:797–800. doi: 10.1007/s10103-013-1432-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crispino A, Figliuzzi MM, Iovane C, Del Giudice T, Lomanno S, Pacifico D, et al. Effectiveness of a diode laser in addition to non-surgical periodontal therapy: Study of intervention. Ann Stomatol (Roma) 2015;6:15–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Micheli G, de Andrade AK, Alves VT, Seto M, Pannuti CM, Cai S, et al. Efficacy of high intensity diode laser as an adjunct to non-surgical periodontal treatment: A randomized controlled trial. Lasers Med Sci. 2011;26:43–8. doi: 10.1007/s10103-009-0753-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dukić W, Bago I, Aurer A, Roguljić M. Clinical effectiveness of diode laser therapy as an adjunct to non-surgical periodontal treatment: A randomized clinical study. J Periodontol. 2013;84:1111–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.110708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loesche WJ, Giordano J, Hujoel PP. The utility of the BANA test for monitoring anaerobic infections due to spirochetes (Treponema denticola) in periodontal disease. J Dent Res. 1990;69:1696–702. doi: 10.1177/00220345900690101301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhalla N, Patil S, Chaubey KK, Narula IS. The detection of BANA micro-organisms in adult periodontitis before and after scaling and root planing by BANA-enzymatic™ test kit: An in vivo study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2015;19:401–5. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.154167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamma JJ, Vasdekis VG, Romanos GE. The effect of diode laser (980 nm) treatment on aggressive periodontitis: Evaluation of microbial and clinical parameters. Photomed Laser Surg. 2009;27:11–9. doi: 10.1089/pho.2007.2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moritz A, Gutknecht N, Doertbudak O, Goharkhay K, Schoop U, Schauer P, et al. Bacterial reduction in periodontal pockets through irradiation with a diode laser: A pilot study. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 1997;15:33–7. doi: 10.1089/clm.1997.15.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]