Abstract

Background

The increase in the use of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging for the detection of prostate cancer has led to the rapid adoption of MRI-guided biopsies (MRGBs). To date, there is limited evidence in the use of MRGB and no direct comparisons between the different types of MRGB. We aimed to assess whether multiparametric MRGBs with MRI-US transperineal fusion biopsy (FB) and cognitive biopsy (CB) improved the management of prostate cancer and to assess if there is any difference in prostate cancer detection with FB compared with CB.

Methods

Patients who underwent an MRGB and a systematic biopsy (SB) from June 2014 to August 2016 on the Central Coast, NSW, Australia, were included in the study. The results of SB were compared with MRGB. The primary outcome was prostate cancer detection and if MRGB changed patient management.

Results

A total of 121 cases were included with a mean age of 65.5 years and prostate-specific antigen 7.4 ng/mL. Seventy-five cases (62%) had a Prostate Imaging and Reporting Data System 4–5 lesions and 46 (38%) had a Prostate Imaging and Reporting Data System 3 lesions. Fifty-six cases underwent CB and 65 underwent FB.

Of the 93 patients with prostate cancer detected, 19 men (20.5%) had their management changed because of the MRGB results. Eight men (9%) had prostate cancer detected on MRGB only and 12 men (13%) underwent radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy based on the MRGB results alone.

There was a trend to a higher rate of change in management with FB compared with CB (29% vs. 18%).

Conclusions

This is one of the first Australian studies to assess the utility of MRGB and compare FB with CB. MRGB is a useful adjunct to SB, changing management in over 20% of our cases, with a trend toward FB having a greater impact on patient management compared with CB.

Keywords: Detection, MRI-guided biopsies, Multiparametric MRI, Prostate cancer

1. Introduction

The current standard diagnostic procedure for men suspected of having prostate cancer is a transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)–guided biopsy or more recently transperineal template grid biopsy, both which involves a systematic, nontargeted sampling of the entire prostate gland. Systematic biopsy (SB) has a detection rate between 27% and 44%,1, 2, 3 with only marginal improvement in prostate cancer detection with saturation biopsy techniques.4 The emergence of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) has now allowed for the identification of suspicious regions in the prostate for cancer before biopsy and may improve the detection of significant prostate cancer with directed biopsies.5

MRI-guided biopsy (MRGB) is a emerging technique with the promise of improving cancer detection rates, increasing accuracy of pathological grading, and potentially decreasing the number of biopsy cores taken. Two systematic reviews have suggested that MRGB has the ability to detect significant prostate cancer in similar or higher rates than standard biopsy; however, the lack of properly designed multicenter trials limits the recommendation for the widespread use of MRGB.6, 7

There are three different types of MRGB, and the optimal technique remains to be determined. The first is cognitive-targeted biopsy, where the operator reviews the MRI images and then manually correlates them with the real-time TRUS images to biopsy the suspicious area. The advantage of this technique is that it does not require any additional, specialized equipment to perform; however, there can be a significant potential for error with sampling the correct region.8 Studies have shown that cognitive biopsy (CB) has a similar prostate cancer detection rate to SB, but with a higher proportion of positive cores.9 The second technique is real-time, in gantry MRGB which has a major disadvantage of being the most complex, requiring prolonged access to expensive MRI machines and being unable to be incorporated into current routine prostate biopsy practices. The third technique is MRI fusion biopsy (FB), where software fuses the MRI images with real-time TRUS images to guide the operator to biopsy the suspicious regions.

Previous MRGB studies have suggested that targeted biopsy combined with SB is superior to SB alone in detecting significant prostate cancer.9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Recent studies directly comparing MRGB with SB have also suggested that FB is associated with increased detection of high-risk prostate cancer, whereas decreasing the detection of low-risk prostate cancer.14, 15, 16 One randomized, controlled trial did not find any difference in the cancer detection rate between FB and SB, but did note that FB improved the detection of anterior tumors.17 A recent meta-analysis of 42 studies found that MRGB improved the detection of clinically significant prostate cancer, but did not improve the overall prostate cancer detection rate.18 Very few studies have directly compared the prostate cancer detection rates between the different modalities of MRGB. The meta-analysis by Wegelin et al18 showed in a pooled analysis that there was no difference between FB and CB, but noted the lack of direct head to head studies. Two studies have found no difference in the cancer detection rate between CB and MRI-fusion transrectal-targeted biopsy.11, 19 A recent study comparing in-gantry MRGB with CB found that there was no difference in the detection of significant prostate cancer, although the in-gantry MRGBs did have a higher percentage of positive-targeted cores than CB.20 To date there have been no studies directly comparing FB performed with a transperineal approach with CB.

The aim of this study is to assess if MRGB improves significant prostate cancer detection and if it provides additional information over SB. The secondary aim of this study was to identify if there were any differences in the rates of significant prostate cancer detection and changes in patient management between FB and CB.

2. Subjects and methods

Patients who underwent simultaneous MRGB and an SB from June 2014 to August 2016 on the Central Coast, NSW, Australia, were included in this study. Institutional review board's approval for this project was authorized (project 0715-056C) by the NSW Health Central Coast Local Health District Research Committee.

2.1. Imaging

All patients underwent mpMRI at a single radiology service, on 1.5T MRI (General Electric Optima MR360, Boston, USA), with an eight-channel body array coil (General Electric Signa HD), with 10 sequences (T1- and T2-weighted whole pelvis, T2-weighted triplanar HR SFOV, diffusion-weighted imaging at b10, b400, b800, and b1400, and dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging) obtained in accordance with the standardized protocols set out by the Prostate Imaging and Reporting Data System (PI-RADS). The mpMRI technical specifications were slightly changed in August 2015 in accordance with PI-RADS version 2.0, which stipulated the acquisition of diffusion-weighted images with b1400 values (before August 2015, the b values used for diffusion-weighted imaging were b400 and b800). All mpMRI imaging was interpreted by at least two experienced MRI radiologists.

2.2. Biopsy

All patients with PI-RADS ≥3 lesions underwent targeted MRGB in conjunction with SB by four urologists each with a prior experience of at least 600 TRUS-guided prostate needle biopsies. MRGB was either CB or FB, according to patient and operator preference. CB was performed via TRUS-guided biopsy. To perform CB, the operator reviewed the mpMRI images and correlated the suspicious areas with those viewed on the real-time TRUS images to perform a TRUS-guided biopsy of the suspicious region.

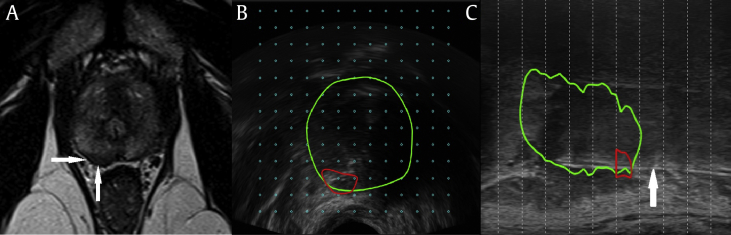

FB was performed using the BioJet Fusion Software System (DK Technologies, Herlev, Denmark) combined with a transperineal grid TRUS platform (BK Medical, Herlev, Denmark). A radiologist experienced in prostate mpMRI was in attendance with PI-RADS ≥3 lesions marked on MRI and fused to the real-time TRUS images for targeted biopsy (Fig. 1). No in-gantry (real-time) MRGBs were performed. The number of targeted biopsies performed was at the discretion of the urologist.

Fig. 1.

MRI and fusion biopsy images from a patient who had 12.5 mm of Gleason 3 + 4 = 7 cancer in three of five fusion-targeted biopsy cores compared with 8.5 mm of Gleason 3 + 3 = 6 cancer on five of 37 systematic biopsy cores. (A) Suspicious hypointense lesion on T2-weighted axial imaging (arrows). (B) Axial fusion of real-time TRUS imaging with the suspicious region (red) in the prostate (green). (C) Hyperechoic needle (white arrow) sampling suspicious region (red) in sagittal plane (green). MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; TRUS, transrectal ultrasound.

Pathology specimens were processed and reported according to ISUP protocols by pathologists from external pathology providers. The pathologists had access to the biopsy results when analyzing the radical prostatectomy specimens.

2.3. Outcome and data analysis

All data were collected in a prospectively maintained database. The results of SB and MRGB were compared with each other and with the available radical prostatectomy specimens. Outcomes measured were significant prostate cancer detection and if MRGB results changed patient management. Significant prostate cancer was defined as Gleason score ≥3 + 4 = 7. Change in patient management was defined as:

-

1.

No cancer to cancer diagnosis (active surveillance or definitive treatment)

-

2.

Cancers suitable for active surveillance (Gleason 3 + 3 = 6 or low volume Gleason 3 + 4 = 7) to significant prostate cancer (definitive treatment recommended)

-

3.

Upgrade from Gleason 3 + 4 = 7 or 4 + 3 = 7 to Gleason ≥4 + 4 = 8 (high-risk disease) changing operative technique to include pelvic lymphadenectomy and non-nerve spare on the side of high-risk disease.

Gleason score at radical prostatectomy was compared with both SB and MRGB.

Data were analyzed with Predictive Analytics Software Statistics version 23.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA).

Normality tests were performed on all continuous variables. Comparisons between groups for normally distributed variables were performed with independent samples t test. Nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis tests were performed for values which were not normally distributed. Fisher exact tests were performed on discrete variables.

3. Results

A total of 121 men were included during the study period for analysis. Fifty-seven men underwent CB, whereas 65 men underwent FB. Patients undergoing FB had significantly more biopsy cores taken on the SB, 25.7 versus 17.4, t(240) = −6.815, P < 0.001, reflecting the higher number of biopsy cores taken on transperineal saturation grid biopsies compared with transrectal biopsies. FB had significantly more guided biopsies taken when compared with CB, 4.6 versus 3.1 t(−240) = −4.163, P < 0.001. There were no other differences in patient demographics between these two groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics.

| All patients (n = 121) | CB (n = 56) | FB (n = 65) | Pa) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr), mean (range) | 65.5 (45–80) | 66.3 (45–80) | 65.0 (48–75) | ns |

| PSA (ng/L), mean (range) | 7.44 (1.3–18) | 7.5 (1.3–18) | 7.3 (2.7–18) | ns |

| DRE ≥ cT2a | 21 (17%) | 12 (21%) | 9 (14%) | ns |

| Prostate volume (cm3), mean (range) | 53 (13–128) | 49.7 (13–125) | 55.2 (16–128) | ns |

| Mean time from MRI to biopsy (mo), mean (range) | 1.2 (0–6) | 1.1 (0–6) | 1.2 (0–4) | ns |

| mpMRI PI-RAD score | ||||

| 3 | 46 (38%) | 18 (32%) | 28 (43%) | ns |

| 4 or 5 | 75 (62%) | 38 (68%) | 37 (57%) | |

| Largest lesion diameter (mm), mean (range) | 15.4 (3–40) | 15.78 (3–36) | 15.1 (5–40) | ns |

| Number of SB cores taken, mean (Range) | 21.9 (9–44) | 17.4 (9–26) | 25.7 (10–44) | <0.001 |

| Number of MRGB cores taken, mean (range) | 3.9 (1–12) | 3.1 (1–7) | 4.6 (1–12) | <0.001 |

CB, cognitive biopsy; DRE, digital rectal examination; FB, fusion biopsy; mpMRI, multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging; MRGB, magnetic resonance imaging–guided biopsy; ns, nonsignificant; PI-RAD, Prostate Imaging and Reporting Data; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; SB, systematic biopsy.

P-values for CB versus FB.

3.1. Comparison of MRGB with SB

Of the 121 men who underwent both MRGB and SB, prostate cancer was detected in a total of 92 patients (76%). There was significantly more prostate cancer detected in PI-RADS 4–5 cases than PI-RADS 3 cases (92% vs. 50%, P < 0.001), and this significant difference was seen in the results of both SB and MRGB (Table 2).

Table 2.

Biopsy characteristics.

| All patients (n = 121) | CB (n = 56) | FB (n = 65) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer detected on SB | ||||

| All cases | ||||

| Total | 84/121 (69%) | 41/56 (73%) | 43/65 (66%) | ns |

| ≥3 + 4 | 61/84 (73%) | 33/41 (81%) | 28/43 (65%) | ns |

| PI-RADS 3 only | ||||

| Total | 19/46 (41%) | 8/18 (44%) | 11/28 (39%) | ns |

| ≥3 + 4 | 12/19 (63%) | 4/8 (50%) | 8/11 (73%) | ns |

| PI-RADS 4–5 only | ||||

| Total | 65/75 (87%) | 33/38 (87%) | 32/37 (86%) | ns |

| ≥3 + 4 | 49/65 (75%) | 29/33 (88%) | 20/32 (62%) | <0.05 |

| Cancer detected on MRGB | ||||

| All cases | ||||

| Total | 80/121 (65%) | 39/56 (70%) | 41/65 (62%) | ns |

| ≥3 + 4 | 61/80 (77%) | 32/39 (82%) | 29/41 (71%) | ns |

| PI-RADS 3 only | ||||

| Total | 15/46 (30%) | 5/18 (29%) | 10/28 (36%) | ns |

| ≥3 + 4 | 7/15 (47%) | 1/5 (10%) | 6/10 (60%) | ns |

| PI-RADS 4–5 only | ||||

| Total | 65/75 (87%) | 34/38 (89%) | 31/37 (84%) | ns |

| ≥3 + 4 | 54/65 (83%) | 31/34 (91%) | 23/31 (74%) | ns |

| Cancer detected with a combined approach | ||||

| All cases | ||||

| Total | 92/121 (76%) | 45/56 (80%) | 47/65 (72%) | ns |

| ≥3 + 4 | 69/92 (75%) | 36/45 (80%) | 33/47 (70%) | ns |

| PI-RADS 3 only | ||||

| Total | 23/46 (50%) | 10/18 (55%) | 13/28 (46%) | ns |

| ≥3 + 4 | 13/23 (57%) | 4/10 (40%) | 9/13 (69%) | ns |

| PI-RADS 4–5 only | ||||

| Total | 69/75 (92%) | 35/38 (92%) | 34/37 (92%) | ns |

| ≥3 + 4 | 56/69 (81%) | 32/35 (91%) | 24/34 (71%) | 0.03 |

| % of positive cores | ||||

| SB (range) | 18 (0–89) | 25 (0–89) | 12 (0–63) | <0.001 |

| MRGB (range) | 46 (0–100) | 54 (0–100) | 39 (0–100) | 0.043 |

∗P-values for CB versus FB.

CB, cognitive biopsy; FB, fusion biopsy; MRGB, magnetic resonance imaging–guided biopsy; ns, nonsignificant; PI-RADS, Prostate Imaging and Reporting Data System; SB, systematic biopsy.

There was no significant difference between SB and MRGB in the prostate cancer detection rate (69% vs. 65%, P = 0.68) or the detection rate of significant prostate cancer (73% vs. 77%, P = 0.72). The detection of significant prostate cancer in PI-RADS 4–5 was also similar between SB and MRGB (75% vs. 83%, P = 0.39) (Table 2).

The percentage of positive cores were significantly higher for MRGB compared with SB, 46% versus 18%, t(242) = 6.684, P < 0.001. The sensitivity for prostate cancer detection was similar between SB (0.91, 95% CI 0.84–0.96) and MRGB (0.87, 95% CI 0.79–0.92), P = 0.48. The sensitivity for significant prostate cancer at biopsy was the same for both SB (0.88, 95% CI 0.79–0.94) and MRGB (0.88, 95% CI 0.79–0.94).

Sixty-eight patients (56%) had concordance between MRGB and SB results (Table 3). Twenty-three patients (19%) had higher Gleason scores on MRGB. Of the 93 patients with prostate cancer detected, 19 men (20.5%) had their management changed because of the MRGB results (Table 4). Eight men (9%) had prostate cancer detected on MRGB with the SB results being clear and 12 men (13%) underwent radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy based on the MRGB results alone. In men, where there was concordance between MRGB and SB results, there was a significantly higher volume of cancer detected per core sample with MRGB, 4.3 mm versus 0.7 mm, t(66) = 5.464, P < 0.001 and a significantly higher number of cores being positive for cancer, 40% versus 13%, t(66) = 5.153, P < 0.001 (Table 5).

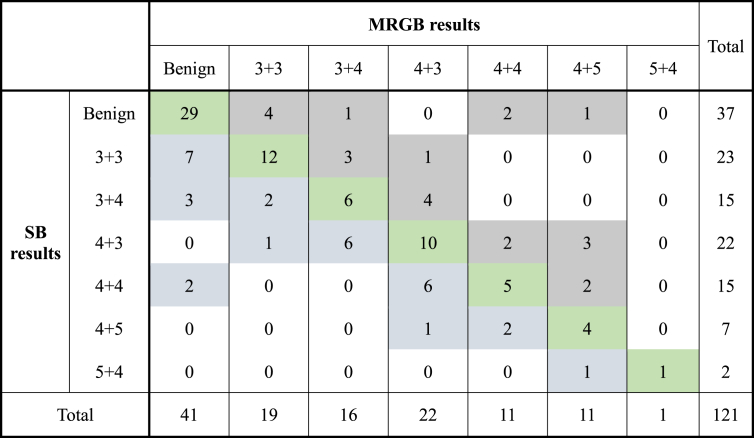

Table 3.

Comparison of Gleason score pathology between MRGB and standard systematic prostate needle biopsy. Green shading designates patients who had an upgrade in Gleason score on their MRGB compared with SB. Grey shading designates concordance between MRGB and SB results. Blue shading designates patients who had a higher Gleason score on SB compared with MRGB. MRGB, magnetic resonance imaging–guided biopsy; SB, systematic biopsy.

Table 4.

Biopsy characteristics in patients, where MRGB results resulted in a change in patient management.

| SB Gleason score | MRGB Gleason score (no. of cases) | PI-RADS score (no. of cases) | MRGB type (no. of cases) | Management based on SB | Change in management with MRGB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No cancer detected | 3 + 3 (4) | 3 (3), 5 (1) | CB (2), FB (2) | PSA follow-up | Active surveillance |

| 3 + 4 (1) | 4 (1) | CB (1) | PSA follow-up | Radical prostatectomy | |

| 4 + 4 (2) | 3 (1), 4 (1) | CB (1), FB (1) | PSA follow-up | Radical prostatectomy | |

| 4 + 5 (1) | 5 (1) | FB (1) | PSA follow-up | Radiotherapy | |

| 3 + 3 | 3 + 3 (1) | 4 (1) | FB (1) | Active surveillance | Radical prostatectomya) |

| 3 + 4 (3) | 4 (3) | CB (1), FB (2) | Active surveillance | Radical prostatectomy | |

| 4 + 3 (1) | 4 (1) | FB (1) | Active surveillance | Radical prostatectomy | |

| 3 + 4 | 4 + 3 (1) | 3(1) | FB (1) | Active surveillance | Radical prostatectomyb) |

| 4 + 3 | 4 + 3 (2) | 4(1), 5(1) | CB (1), FB (1) | Nerve spare without node dissection | Non-nerve spare and extended lymph node dissectionc) |

| 4 + 5 (3) | 4(1), 5 (2) | CB (1), FB (2) | Nerve spare without node dissection | Non-nerve spare and extended lymph node dissection | |

| Total | CB (7), FB (12) |

CB, cognitive biopsy; FB, fusion biopsy; MRGB, magnetic resonance imaging–guided biopsy; PI-RADS, Prostate Imaging and Reporting Data System; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; SB, systematic biopsy.

Low volume 1 mm on SB, high volume 22 mm on MRGB, final pathology Gleason 3 + 4 on radical prostatectomy.

Low volume 3 mm on SB, high volume 13 mm on MRGB.

Low volume 1 mm and 3 mm on SB, high volume 20 mm and 24 mm on MRGB.

Table 5.

Comparison of biopsy characteristics in patients where there was concordance between the MRGB and SB Gleason scores.

| SB (n = 37) | MRGB (n = 37) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % of positive cores (range) | 13 (0–89) | 40 (0–100) | <0.001 |

| mm of Ca detected/core (range) | 0.66 (0.03–4.75) | 4.3 (0.09–12) | <0.001 |

MRGB, magnetic resonance imaging–guided biopsy; SB, systematic biopsy.

3.2. Comparison of CB with FB

CB had a significantly higher core positivity rate than FB, 54% versus 39%, t(119) = 2.047, P = 0.043, although this difference was also seen on the SB for these two groups, 25% versus 12%, t(119) = 3.965, P < 0.001.

There was no difference between CB and FB in the overall prostate cancer detection rate (70% vs. 63%, P = 0.45) or the detection rate of significant prostate cancer (82% vs. 71%, P = 0.084). In the PI-RADS 4–5 cases, despite SB detecting significantly more low-risk prostate cancer in the FB group compared with the CB group (38% vs. 12%, P = 0.02), there was no significant difference in the detection of Gleason ≥3 + 4 prostate cancer on the MRGB results between the CB and FB groups (91% vs. 74%, P = 0.1).

There were higher rates of change in management in the FB (29% vs. 18%), but this was not statistically significant because of small numbers (P = 0.3). The sensitivity of CB and FB for prostate cancer was similar, 0.87 (95% CI 0.74–0.94) versus 0.87 (95% CI 0.75–0.94), respectively. The sensitivity for significant prostate cancer was also similar for CB, 0.89 (95% CI 0.75–0.96) compared with FB, 0.88 (95% CI 0.73–0.95), P = 0.99.

3.3. Comparison of SB and MRGB results with radical prostatectomy pathology

Forty-three patients underwent radical prostatectomy after prostate biopsy. There was concordance in Gleason score between radical prostatectomy specimen and biopsy in 49% cases for MRGB and 42% cases for SB, with no significant differences between the two groups (P = 0.76). MRGB alone would have missed three cancers (7%), whereas SB alone would have missed two cancers (5%). For the nonconcordant cases, both MRGB and SB tended to undergrade the final pathology (Table 6). If MRGB and SB results were combined, then concordance to radical prostatectomy Gleason score improved to 58%.

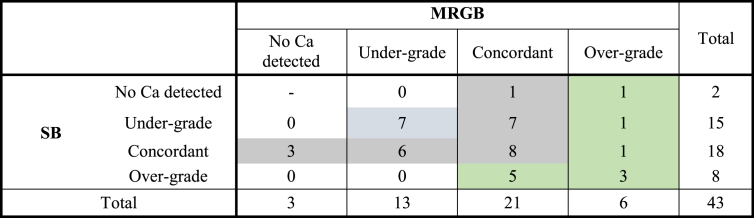

Table 6.

Comparison of systematic and MRGB to final radical prostatectomy specimen in 43 patients. Blue shading indicates where a combined biopsy approach resulted in undergrading, grey shading indicates overgrading, and green shading indicates concordance to the final radical prostatectomy Gleason score. MRGB, magnetic resonance imaging–guided biopsy; SB, systematic biopsy.

4. Discussion

Our study adds to the growing literature on the utility of MRGB. Our study highlights the value of performing MRGB in addition to the standard SB, with 20% of patients with prostate cancer undergoing a change in management because of an upgrade in Gleason score on the MRGB compared with the SB. Nearly 10% of prostate cancer cases were detected on MRGB alone, and 13% of prostate cancer cases underwent correct definitive treatment of radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy based on the MRGB result.

Our study replicates most findings of a recent meta-analysis by Wegelin et al,18 which pooled data from 43 studies to assess the benefit of MRGB for prostate cancer detection and compared the three current methods of MRGB. They reported a slightly lower sensitivity for prostate cancer detection than that found in our study (0.81 for MRGB and 0.83 for SB compared with 0.87 and 0.91, respectively, in our study), but similarly found no difference in the overall prostate cancer detection rate between MRGB and SB. Some previous studies have shown that MRGB detects more cases of significant prostate cancer than SB14, 18; however, our study did not replicate this finding. Although the sensitivity of MRGB for significant prostate cancer in our study was similar to that reported in Wegelin et al (0.88 vs. 0.90), our sensitivity of SB was significantly higher than that reported in the literature (0.88 vs. 0.79). One contributing factor may be that our operators where not blinded to the MRI findings when performing the SB, and thus may have inadvertently performed a more “targeted” biopsy during the SB resulting in our higher detection rate on SB than that reported in the literature.

Our study adds to the literature which supports the use of MRGB in conjunction with SB in the workup of men with suspected prostate cancer. Without MRGB, nearly one in five patients with prostate cancer would have undergone incorrect management. MRGB used in conjunction with SB increased Gleason score concordance with the radical prostatectomy specimen by nearly 10%. Some previous studies have suggested that MRGB may be able to replace SB, as the addition of SB to the MRGB only increases the detection of low-risk cancer without greatly increasing the detection of significant prostate cancer.14 Our study does not currently support the use of MRGB without SB, as MRGB used alone in our case series would have missed five cases (5%) of significant prostate cancer and led to a significant undergrading in four cases (4%).

Very few studies have directly compared the prostate cancer detection rates between the different modalities of MRGB. A recent study comparing in-gantry MRGB with CB found that in-gantry MRGBs result in a higher percentage of positive-targeted cores. However; there was no significant difference in the overall prostate cancer detection rate or the detection of significant prostate cancer between the two modalities.20 The meta-analysis by Wegelin et al showed in a pooled analysis that there was no difference between FB and CB, but noted the lack of direct head to head studies.18 Two studies have found no difference in the cancer detection rate between CB and MRI-fusion transrectal-targeted biopsy.11, 19 Our study is one of the first to directly compare FB (performed with a transperineal approach) and CB. Our study showed that FB does not significantly improve the detection of all prostate cancer or clinically significant prostate cancer. In our study, there were no statistically significant differences in the significant cancer detection rate between CB and FB (91% vs. 74%). This is despite significantly more biopsy cores taken on SB and MRGB in the FB group, as these cases were performed under general anesthetic, whereas the patients in the CB group had TRUS biopsies performed in the office under local anesthetic. There was, however, a nonstatistically significant trend to have more cases in the FB group with MRGB results which changed their prostate cancer management (29% vs. 18%, P = 0.29). Given that nearly one in three patients undergoing FB had their management changed by this additional technique, this shows promise for future research in demonstrating the utility of FB given its longer procedural time, higher setup costs and need for specialized equipment and software.

We acknowledge several limitations in our comparison of FB and CB. First, our patients were not randomized and the type of MRGB performed was clinician dependent. Secondly, our numbers are small and our operators were experienced at transrectal biopsy, but were on their initial learning curve for transperineal biopsy, and thus may have impacted on the true accuracy of FB early in their experience. Our study is also limited in its single-center design and further multicenter trials will be required in the future to validate our findings. Thirdly, MRGB and SB were performed by the same operators who were not blinded to the mpMRI results. This may have led to inadvertent targeting of the suspicious area on the SB and resulted in our higher detection rate on SB compared with MRGB when compared with other studies. Fourthly, we are comparing FB of transperineal biopsy and CB of TRUS biopsy; however, this reflects our current practice where urologists use both techniques.

Despite these limitations, however, our study shows that the addition of MRGB to the SB changes management in over 20% of cases of prostate cancer. Our study indicates that MRGB can be successfully performed in our Australian center; however, they will still miss around 12% of cancers, and thus our study does not support the use of MRGB without SB. Furthermore, this is one of the first studies to directly compare FB with CB; highlighting that both are useful adjuncts to SB, with a trend toward FB having a greater impact on changing patient management compared with CB.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prnil.2017.10.003.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Babaian R.J., Toi A., Kamoi K., Troncoso P., Sweet J., Evans R. A comparative analysis of sextant and an extended 11-core multisite directed biopsy strategy. J Urol. 2000;163(1):152–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Presti J.C., O'dowd G.J., Miller M.C., Mattu R., Veltri R.W. Extended peripheral zone biopsy schemes increase cancer detection rates and minimize variance in prostate specific antigen and age related cancer rates: results of a community multi-practice study. J Urol. 2003;169(1):125–129. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eskew L.A., Bare R.L., McCullough D.L. Systematic 5 region prostate biopsy is superior to sextant method for diagnosing carcinoma of the prostate. J Urol. 1997;157(1):199–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones J.S., Patel A., Schoenfield L., Rabets J.C., Zippe C.D., Magi-Galluzzi C. Saturation technique does not improve cancer detection as an initial prostate biopsy strategy. J Urol. 2006;175(2):485–488. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson J.E., Moses D., Shnier R., Brenner P., Delprado W., Ponsky L. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging guided diagnostic biopsy detects significant prostate cancer and could reduce unnecessary biopsies and over detection: a prospective study. J Urol. 2014;192(1):67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gayet M., van der Aa A., Beerlage H.P., Schrier B.P., Mulders P.F., Wijkstra H. The value of magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasonography (MRI/US)-fusion biopsy platforms in prostate cancer detection: a systematic review. BJU Int. 2016;117(3):392–400. doi: 10.1111/bju.13247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore C.M., Robertson N.L., Arsanious N., Middleton T., Villers A., Klotz L. Image-guided prostate biopsy using magnetic resonance imaging–derived targets: a systematic review. Eur Urol. 2013;63(1):125–140. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson J., Lawrentschuk N., Frydenberg M., Thompson L., Stricker P. The role of magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis and management of prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2013;112(S2):6–20. doi: 10.1111/bju.12381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasivisvanathan V., Dufour R., Moore C.M., Ahmed H.U., Abd-Alazeez M., Charman S.C. Transperineal magnetic resonance image targeted prostate biopsy versus transperineal template prostate biopsy in the detection of clinically significant prostate cancer. J Urol. 2013;189(3):860–866. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siddiqui M.M., Rais-Bahrami S., Turkbey B., George A.K., Rothwax J., Shakir N. Magnetic resonance imaging/ultrasound–fusion biopsy significantly upgrades prostate cancer versus systematic 12-core transrectal ultrasound biopsy. Eur Urol. 2013;64(5):713–719. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.05.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wysock J.S., Rosenkrantz A.B., Huang W.C., Stifelman M.D., Lepor H., Deng F.-M. A prospective, blinded comparison of magnetic resonance (MR) imaging–ultrasound fusion and visual estimation in the performance of MR-targeted prostate biopsy: the PROFUS trial. Eur Urol. 2014;66(2):343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sonn G.A., Chang E., Natarajan S., Margolis D.J., Macairan M., Lieu P. Value of targeted prostate biopsy using magnetic resonance–ultrasound fusion in men with prior negative biopsy and elevated prostate-specific antigen. Eur Urol. 2014;65(4):809–815. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Filson C.P., Natarajan S., Margolis D.J., Huang J., Lieu P., Dorey F.J. Prostate cancer detection with magnetic resonance-ultrasound fusion biopsy: The role of systematic and targeted biopsies. Cancer. 2016;122(6):884–892. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siddiqui M.M., Rais-Bahrami S., Turkbey B., George A.K., Rothwax J., Shakir N. Comparison of MR/ultrasound fusion–guided biopsy with ultrasound-guided biopsy for the diagnosis of prostate cancer. JAMA. 2015;313(4):390–397. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.17942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borkowetz A., Platzek I., Toma M., Renner T., Herout R., Baunacke M. Direct comparison of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) results with final histopathology in patients with proven prostate cancer in MRI/ultrasonography-fusion biopsy. BJU Int. 2016;118(2):213–220. doi: 10.1111/bju.13461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meng X., Rosenkrantz A.B., Mendhiratta N., Fenstermaker M., Huang R., Wysock J.S. Relationship between prebiopsy multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), biopsy indication, and MRI-ultrasound fusion–targeted prostate biopsy outcomes. Eur Urol. 2016;69(3):512–517. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tonttila P.P., Lantto J., Pääkkö E., Piippo U., Kauppila S., Lammentausta E. Prebiopsy multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging for prostate cancer diagnosis in biopsy-naive men with suspected prostate cancer based on elevated prostate-specific antigen values: results from a randomized prospective blinded controlled trial. Eur Urol. 2016;69(3):419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wegelin O., van Melick H.H., Hooft L., Bosch J.R., Reitsma H.B., Barentsz J.O. Comparing three different techniques for magnetic resonance imaging-targeted prostate biopsies: a systematic review of in-bore versus magnetic resonance imaging-transrectal ultrasound fusion versus cognitive registration. Is There a Preferred Technique? Eur Urol. 2017;71(4):517–531. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puech P., Rouvière O., Renard-Penna R., Villers A., Devos P., Colombel M. Prostate cancer diagnosis: multiparametric MR-targeted biopsy with cognitive and transrectal US–MR fusion guidance versus systematic biopsy—prospective multicenter study. Radiology. 2013;268(2):461–469. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13121501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yaxley A.J., Yaxley J.W., Thangasamy I., Ballard E., Pokorny M. Comparison between target MRI in-gantry and cognitive target transperineal or transrectal guided prostate biopsies for PIRADS 3-5 MRI lesions. BJU Int. 2017 doi: 10.1111/bju.13971. (in print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.