Abstract

background and objectives:

Because physicians’ practices could be modified to reduce missed opportunities for human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination, our goal was to: (1) describe self-reported practices regarding recommending the HPV vaccine; (2) estimate the frequency of parental deferral of HPV vaccination; and (3)identify characteristics associated with not discussing it.

methods:

A national survey among pediatricians and family physicians (FP) was conducted between October 2013 and January 2014. Using multivariable analysis, characteristics associated with not discussing HPV vaccination were examined.

results:

Response rates were 82% for pediatricians (364 of 442) and 56% for FP (218 of 387). For 11–12 year-old girls, 60% of pediatricians and 59% of FP strongly recommend HPV vaccine; for boys,52% and 41% ostrongly recommen. More than one-half reported ≥25% of parents deferred HPV vaccination. At the 11–12 year well visit, 84% of pediatricians and 75% of FP frequently/always discuss HPV vaccination. Compared with physicians who frequently/always discuss, those who occasionally/rarely discuss(18%) were more likely to be FP (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]: 2.0 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.1–3.5), be male (aOR: 1.8 [95% CI: 1.1–3.1]), disagree that parents will accept HPV vaccine if discussed with other vaccines (aOR: 2.3 [95% CI: 1.3–4.2]), report that 25% to 49% (aOR: 2.8 [95% CI: 1.1–6.8]) or ≥50% (aOR: 7.8 [95% CI: 3.4–17.6]) of parents defer, and express concern about waning immunity (aOR: 3.4 [95% CI: 1.8–6.4]).

conclusions:

Addressing physicians’ perceptions about parental acceptance of HPV vaccine, the possible advantages of discussing HPV vaccination with other recommended vaccines, and concerns about waning immunity could lead to increased vaccination rates.

Almost 1 in 4 people in the United States is infected with at least 1 strain of human papillomavirus (HPV), and ~27 000 cancers are likely caused by HPV each year.1,2 Among these HPV-attributable cancers, 17 600 cases were diagnosed in women, with >10 000 of these cancers occurring in the cervix; 9300 cases were diagnosed in men, with >7000 occurring in the oropharynx.1 Although cervical cancers are more common, the incidence of oropharyngeal cancers is increasing, and these cancers are 4 times more common in men than in women.1,3,4 HPV infection also causes the majority of vulvar, vaginal, and anal cancers among women, and penile and anal cancers among men.1,5

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended the HPV vaccine for routine use in girls in 2006 and for boys in 2011.6 The committee recommended the vaccine for 11- to 12-year-olds because it is most effective if given before initiation of sexual activity and exposure to HPV and because 2 additional vaccines, the quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine and the tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine, are also recommended at this age. HPV vaccine coverage has remained lower than coverage for the other recommended adolescent vaccines.7 National data suggest that 60% of 13- to 17-year-old girls have received at least 1 dose of HPV vaccine, and 40% have received all 3 doses. Boys have lower HPV vaccination rates than girls, with 42% coverage for 1 dose and 22% coverage for all 3 doses among 13- to 17-year-olds.

Missed opportunities for HPV vaccination at 11 to 12 years of age are common.8 Several factors, including financial issues, patient and parent refusal or deferral, and health care providers’ practices, likely contribute to these missed opportunities.9 Because physicians’ practices could be modified to reduce missed opportunities and increase HPV vaccine coverage, the goal of the present study was to understand physicians’ current perspectives and practices related to HPV vaccination for girls and boys. Using a national sample of pediatricians and family physicians (FP), our objectives were to: (1) describe physicians’ self-reported practices regarding recommending and administering the HPV vaccine; (2) estimate how frequently physicians report parental deferral of HPV vaccination for their children in different age groups; and (3) estimate how frequently physicians discuss the HPV vaccine and identify physician and practice characteristics associated with not discussing the HPV vaccine at the 11- to 12-year-old well-child visit.

METHODS

Study Setting

The Vaccine Policy Collaborative Initiative, a program designed collaboratively with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to assess primary care physicians’ attitudes regarding vaccine-related issues, administered a survey to a national network of pediatricians and FP. The human subjects review board at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus approved the study as exempt research.

Population

The survey was conducted among networks of physicians previously recruited from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) to respond to several surveys annually.10 After obtaining twice the number of recruits needed for each network, a quota strategy was applied to assure the representativeness of the samples.10,11 In a previous evaluation, demographic characteristics, practice attributes, and reported attitudes about vaccination issues were shown to be generally similar between network physicians and physicians of the same specialties randomly sampled from the American Medical Association master physician listing.10

Survey Design

The survey instrument was developed in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It included 21 questions, most with multiple parts, about characteristics of physicians and practices; physicians’ practices related to administration of, recommendation for, and discussion of the HPV vaccine; reasons for deferring discussion of the HPV vaccine; physicians’ knowledge and attitudes about HPV infection and the HPV vaccine; and physicians’ estimates of how often parents had deferred the HPV vaccine when it had been offered to their child. The survey also included questions about discussion of sexual health issues and barriers to vaccine administration, but these questions were not included in the present analysis. The survey was pretested in an advisory panel of 8 pediatricians and 5 FP from across the country and was pilot-tested among 81 pediatricians and 19 FP.

Physicians’ self-reported practices and attitudes about the HPV vaccine and HPV infection were measured by using 4-point Likert scales. Physicians’ knowledge about the HPV vaccine and HPV-related diseases were measured by using statements to which respondents answered “agree,” “disagree,” or “don’t know/ not sure.” Finally, physicians’ experience with deferral of the HPV vaccine was measured by asking them to estimate the proportion of parents who had deferred in the following categories: <1%, 1% to 9%, 10% to 24%, 25% to 49%, and ≥50%.

Survey Administration

The survey was administered between October 2013 and January 2014 by using an Internet version or regular mail based on physicians’ preferences. The Internet survey was administered with a Web-based program (Vovici Corporation, Dulles, Virginia). The Internet group received an initial e-mail with a link to the survey and up to 8 e-mail reminders to complete the survey; the mail group received an initial mailing and up to 2 additional mailed surveys at 2-week intervals. The Internet nonresponders also received up to 2 paper surveys by mail. The physicians received no financial incentives for their participation.

Analytic Methods

Internet and mail surveys were pooled for all analyses because provider attitudes have been found to be comparable when obtained by using either method.12 We compared pediatricians and FP responses by using χ2 tests for questions with dichotomous responses and Mantel-Haenszel tests for questions with Likert scale responses. When responses of the pediatricians and FP were similar, they were combined for subsequent analyses. The Cochran-Armitage test for trend was used to compare the strength of recommendation for HPV vaccination across different age groups, and McNemar’s test was used to compare the strength of recommendation between boys and girls in each age group.

A bivariate analysis was also conducted to compare the practice characteristics of physicians who reported experiencing more parental deferral (≥25%) versus physicians who reported less parental deferral (<25%) at the 11- to 12-year-old visit. Because physicians’ reported estimates of parental deferral were not significantly different between 11-to 12-year-old boys and girls overall, 1 deferral variable was created for each physician by choosing the higher estimate of deferral if an individual physician’s response differed for boys and girls.

We compared physicians who reported that they rarely/never or occasionally discussed the HPV vaccine at the 11-to 12-year-old well-child visit with physicians who reported that they frequently or almost always/always discussed HPV vaccination at this age. Physicians who indicated that they rarely see 11- to 12-year-old girls or boys were excluded. Predictor variables were chosen based on existing literature and our hypothesis that physicians who had experienced more parental deferral at the 11- to 12-year-old visit would be less likely to discuss HPV vaccination at this visit. We compared physician and practice characteristics, belief that it is necessary to discuss sexual health issues when discussing the HPV vaccine, belief that parents are more likely to accept the HPV vaccine if discussed in the context of other vaccines given at the 11- to 12- year-old visit, knowledge that the antibody response to the HPV vaccine is stronger in younger adolescents compared with adults, concern about waning immunity, and estimates of the proportion of parents who had deferred the HPV vaccine for the discussion outcome; Wilcoxon tests and χ2 tests were used, as appropriate. Predictor variables with a P value ≤.25 were included in a multivariable logistic regression model. Variables were retained in the final model for P < .05.

Finally, we conducted multivariable analyses comparing physicians who reported that they strongly recommend the HPV vaccine for 11- to 12-year-olds versus those who do not, with separate analyses for girls and boys. We used the same predictor variables and methods as described earlier for the analysis of discussion of HPV vaccine at the 11- to 12-year-old visit.

RESULTS

Response Rates and Respondent Characteristics

The survey response rate was 70% overall (582 of 829), with 82% of pediatricians (364 of 442) and 56% of FP (218 of 387) responding. Pediatrician responders did not differ from nonresponders in terms of gender, age, practice type, urban versus rural location, or region of the country. Compared with nonresponders, FP responders were more likely to be female and less likely to practice in the southern United States (Table 1).

Table 1.

Physician and Practice Characteristics

| Physician and Practice Characteristics | Respondents, % |

Nonrespondents, % |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pediatricians, (n = 364) |

FP, (n = 218) | Pediatricians, (n = 78) |

FP, (n = 169) | |

| Female gender | 64 | 50* | 65 | 35* |

| Setting | ||||

| Private practice | 77 | 70 | 77 | 75 |

| Hospital or clinic | 21 | 24 | 18 | 21 |

| HMO | 1 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| Location | ||||

| Urban, inner-city | 15 | 36 | 14 | 37 |

| Urban, not inner-city | 75 | 52 | 77 | 58 |

| Rural | 10 | 12 | 9 | 5 |

| Region | ||||

| Midwest | 20 | 29* | 18 | 26* |

| Northeast | 23 | 17 | 23 | 16 |

| South | 33 | 29 | 39 | 41 |

| West | 24 | 25 | 21 | 17 |

| Age, mean ± SD,y | 49.3 ±10.7 | 53.5 ± 9.7 | 49.3 ± 10.6 | 52.1 ± 10.3 |

| Administer HPV vaccine in the office | ||||

| To female patients | 99 | 87 | — | — |

| To male patients | 98 | 81 | — | — |

| Proportion of 11-to 18-year-old patients | ||||

| <10% | 2 | 44 | — | — |

| 10%–29% | 22 | 50 | — | — |

| 30%–49% | 67 | 5 | — | — |

| ≥50% | 9 | 1 | — | — |

| Proportion of patients with Medicaid or CHIP | ||||

| <10% | 23 | 38 | — | — |

| 10%–24% | 21 | 28 | — | — |

| 25%–49% | 20 | 22 | — | — |

| ≥50% | 35 | 12 | — | — |

| Proportion of Hispanic/Latino patients | ||||

| <10% | 42 | 62 | — | — |

| 10% to 24% | 28 | 23 | — | — |

| ≥25% | 30 | 15 | — | — |

| Proportion of black/African- American patients | ||||

| <10% | 40 | 64 | — | — |

| 10% to 24% | 36 | 22 | — | — |

| ≥25% | 24 | 14 | — | — |

CHIP, Children’s Health Insurance Program; HMO, health maintenance organization.

P ≤ .05 for comparison between responders and nonresponders. A dash indicates that data are not available.

Physicians’ Current Practices

Ninety-nine percent of pediatricians and 87% of FP administer the HPV vaccine to 11- to 18-year-old girls in their practices, whereas 98% of pediatricians and 81% of FP administer the vaccine to boys. Physicians were more likely to strongly recommend the HPV vaccine for older age groups (Mantel- Haenszel χ2 tests, P < .0001 for girls and boys), and in every age group, physicians were more likely to strongly recommend the vaccine for girls than for boys (McNemar’s test, P < .0001 for each age group) (Table 2). Pediatricians were more likely to strongly recommend the HPV vaccine than FP except for 11- to 12-year-old girls (P ≤.0001).

Table 2.

Pediatrician and FP Strength of Recommendation for the HPV Vaccine in Male and Female Subjects According to Age Group (n = 557)

| Age Group | Gender | Strongly Recommend |

Recommend But Not Strongly |

No Recommendation |

Recommend Against |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pediatricians | FP | Pediatricians | FP | Pediatricians | FP | Pediatricians | FP | ||

| 11- to 12-year-olds | Female | 60 | 59 | 34 | 34 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 2 |

| Male | 52 | 41 | 38 | 45 | 10 | 11 | 0 | 3 | |

| 13- to 15-year-olds | Female | 87 | 79 | 12 | 17 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Male | 78 | 61 | 20 | 30 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 2 | |

| 16- to 18-year-olds | Female | 94 | 82 | 6 | 15 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Male | 85 | 64 | 14 | 26 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 3 | |

Data are presented as %.

Physicians’ Report of Parental Deferral of HPV Vaccination

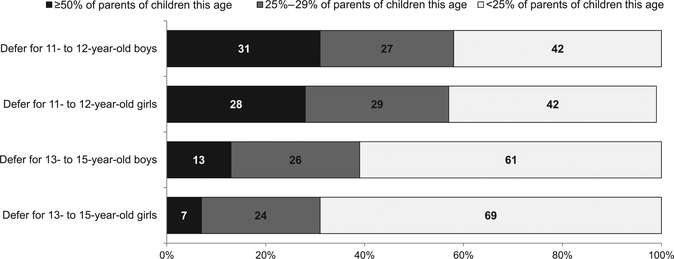

More than one-half of physicians reported that when they offered the HPV vaccine, ≥25% of parents deferred vaccination for their 11- to 12-year-old children (Fig 1). Physicians reported that parental deferral of the HPV vaccine was more common for 11- to 12-year-olds than for 13- to 15-year-olds (P < .0001 for both genders); frequency of deferral did not differ between 11- to 12-year- old girls and boys (P = .56) but was slightly higher for boys than for girls in the 13- to 15-year-old age group (P < .0001). As shown in Table 3, being in private practice, in a suburban location, having ≥50% of patients with private insurance, and having ≥50% of patients who are non-Hispanic white were characteristics associated with reporting higher frequency of parental deferral. Eighty-eight percent of pediatricians and 67% of FP reported that they were very likely to bring up HPV vaccination again at a future visit if a parent had previously deferred initiation of the vaccine series; 10% of pediatricians and 23% of FP were somewhat likely to bring it up again; and 2% of pediatricians and 10% of FP were not at all or only a little likely to bring it up again.

FIGURE 1.

Physicians’ report of parental deferral of the HPV vaccine for their boys and girls in different age groups (n = 525).

Table 3.

Practice Characteristics Associated With Physician Report of Parental Deferral of the HPV Vaccine for their 11- to 12-Year-Old Children (n = 543)

| Practice Characteristic | Physician Report of Proportion of Parents Who Defer |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| <25% (n = 190) | ≥25% (n = 353) | p | |

| Practice specialty | |||

| FP | 36 | 34 | — |

| Pediatricians | 64 | 66 | .72 |

| Setting | |||

| Private practice | 64 | 82 | — |

| HMO | 3 | 15 | — |

| Hospital or clinic | 33 | 3 | .0001 |

| Location | |||

| Urban | 28 | 16 | — |

| Suburban | 60 | 74 | — |

| Rural | 12 | 10 | .002 |

| Region | |||

| Midwest | 23 | 23 | — |

| Northeast | 17 | 24 | — |

| South | 31 | 32 | — |

| West | 29 | 21 | .09 |

| What percentages of your patients have private insurance? | |||

| 0–24% | 36 | 15 | — |

| 25%−49% | 23 | 18 | — |

| >50% | 41 | 67 | <.0001a |

| What percentages of your patients are non-Hispanic white? | |||

| 0–24% | 29 | 13 | — |

| 25%−49% | 20 | 18 | — |

| >50% | 50 | 69 | <.0001a |

Data are presented as %. HMO, health maintenance organization.

According to the Mantel-Haenszel test.

Physician Discussion of HPV Vaccine

As shown in Table 4, 67% of pediatricians and 50% of FP almost always or always discuss HPV vaccination among 11- to 12-year- olds. Among the 118 pediatricians who did not almost always/always discuss the HPV vaccine at well visits for all age groups, the most commonly reported reasons for not discussing the topic were: “I know the patient is not yet sexually active” (54%), “I think the patient is too young” (38%), “the patient is already getting other vaccines at that visit” (35%), and “I expect the parents to refuse” (29%). Among the 104 FP who did not almost always/always discuss the HPV vaccine, the most commonly reported reasons for not discussing the vaccine were: “I don’t have enough time to discuss” (47%), “I know the patient is not yet sexually active” (35%), “I think the patient is too young” (28%), and “I expect the parents to refuse” (28%).

Table 4.

Pediatrician- and FP-Reported Frequency of Discussion of HPV Vaccine Among Different Age Groups (n = 557)

| Age Group | Almost Always or Always Discuss |

Frequently Discuss |

Occasionally Discuss |

Rarely or Never Discuss |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pediatricians | FP | Pediatricians | FP | Pediatricians | FP | Pediatricians | FP | |

| 11- to 12-year-olds | 67 | 50 | 17 | 26 | 13 | 18 | 4 | 7 |

| 13- to 15-year-olds | 87 | 64 | 10 | 25 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 3 |

Data are presented as %.

Physician and Practice Characteristics Associated With Discussion and Recommendation of HPV Vaccine

Compared with physicians who frequently or almost always/always discuss the HPV vaccine at the 11- to 12-year well-child visits for girls and boys (n = 419), those who rarely/ never or only occasionally discuss the HPV vaccine (n = 92) were more likely to be FP (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]: 2.0 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.1–3.5]), be male (aOR: 1.8; 95% CI 1.1–3.1), disagree that parents are more likely to accept the HPV vaccine if discussed in context of other vaccines (aOR: 2.3 [95% CI: 1.3–4.2]), report 25% to 49% (aOR: 2.8 [95% CI: 1.1–6.8]) or ≥50% (aOR: 7.8 [95% CI: 3.4–17.6]) of parents defer the vaccine when offered to their child at 11 to 12 years of age, and express concern about waning immunity (aOR: 3.4 [95% CI: 1.8–6.4]). Practice location, setting, knowledge that the HPV vaccine produces a stronger antibody response in younger adolescents compared with adults, and belief that it is necessary to discuss sexual health issues were not significantly associated with physician discussion of HPV vaccination at 11 to 12 years.

In the multivariable analysis comparing physicians who strongly recommend giving the vaccine to girls at 11 to 12 years of age versus physicians who do not strongly recommend the vaccine using the same predictor variables described earlier, significant factors and aORs were similar to those reported except specialty and physician gender were not significant factors. In the multivariable analysis comparing physicians who strongly recommend the vaccine be given to boys at 11 to 12 years of age versus physicians who do not recommend it, results were similar to those reported earlier except physician gender and concern about waning immunity were not significant factors.

DISCUSSION

Our survey of a nationally representative sample of pediatricians and FP indicates that although most administer the HPV vaccine, more than one-third are not strongly recommending this vaccine at age 11 to 12 years and are less likely to strongly recommend the vaccine for boys. Similarly, one-third of pediatricians and one-half of FP do not always discuss HPV vaccination at the 11- to 12-year-old visit. FP, physicians who are concerned about waning immunity, physicians who disagree that parents are more likely to accept the HPV vaccine if discussed in the context of other recommended vaccines, and physicians who perceive that parents are likely to defer the vaccine for their children are less likely to discuss HPV vaccination at 11 to 12 years of age.

An analysis of data from the 2010 National Immunization Survey- Teen indicated that 31% of parents of teen-aged girls had delayed or refused the HPV vaccine.13 Compared with girls whose parents had neither delayed nor refused the HPV vaccine, girls whose parents had delayed the vaccine were more likely to be non-Hispanic white, live in a higher income household, and not be Vaccines for Children Program entitled. Although we cannot compare our results regarding physicians’ perceptions of parental delay directly with the data from the National Immunization Survey- Teen, our findings were similar in that physicians in private practice, with a higher percentage of patients with private insurance, and a higher percentage of non-Hispanic white patients were more likely to report parental deferral than other physicians.

Physicians’ perceptions of parental attitudes may not always be accurate. A recent study asked parents to rank the importance of several vaccines on a scale of 0 to 10 and then asked health care providers to estimate parental responses.14 The median ranking from parents for the HPV vaccine was 9.3, which was similar to their rankings for other vaccines. However, the median physician estimate of parental ranking for the HPV vaccine was 5.2, which was considerably lower than physician estimates for other vaccines (mostly >9).

Physicians’ perceptions are important for vaccine delivery because physicians who perceive that parents are likely to defer HPV vaccination are less likely to discuss the vaccine at the 11- to 12-year- old visit based on findings from our study and others.15,16 In addition, we found that 12% of pediatricians and 33% of FP were only somewhat likely or unlikely to bring up the HPV vaccine again if parents initially deferred. If physicians do not discuss the vaccine, they have no opportunity to provide a strong recommendation or to understand and address parents’ knowledge gaps or to elicit concerns. Physicians themselves may have knowledge gaps about the prevalence of HPV infection and burden of HPV-attributable cancers. Our finding that physicians were less likely to strongly recommend the HPV vaccine to boys than to girls is concerning given that more than one-third of HPV-attributable cancers occur in men.1 The lack of a strong recommendation may contribute to missed opportunities for HPV vaccination because it is accepted that a strong recommendation for HPV vaccination from a physician is associated with receipt of the vaccine.9,17–19 Qualitative and survey data, as well as some preliminary intervention studies, suggest that many parents may accept the HPV vaccine for their child at 11 to 12 years if their knowledge gaps and concerns are addressed by the physician in conjunction with a strong recommendation for vaccination.8,20–24

In addition to expecting parents to refuse the HPV vaccine, FP and pediatricians who do not routinely discuss HPV vaccination at the 11- to 12-year-old visit reported patient age and knowing the patient is not sexually active as reasons for deferring discussion. Physicians may defer discussion of HPV vaccination because they perceive that their patient population is likely to return for visits later in adolescence. However, in studies of adolescent visit patterns with mainly white and privately insured patients, preventive care visits declined after the age of 13 to 14 years.25,26 Physicians may perceive that their patient population is unlikely to acquire HPV. Although the average age of sexual debut differs according to gender, race, and ethnic group, approximately one- third of all youth will have had sexual intercourse by 16 years of age, and HPV infection occurs within a few years of becoming sexually active.6,27 Physicians who defer discussion of HPV vaccine may change their practices if they understand these reasons for vaccinating early. In our multivariable analysis, physicians who were concerned about waning immunity were less likely to routinely discuss the HPV vaccine at the 11- to 12-year-old visit. This concern may be partly based on the recommendation for a booster dose of the quadrivalent meningoccocal conjugate vaccine at age 16 years after a prior recommendation for 1 dose at age 11 to 12 years.28 The data available show no evidence of waning protection for 9 to 10 years’ postvaccination.6,29 Physicians should be provided with this information and updated as new data emerge over time. Because FP are less likely to routinely discuss the HPV vaccine at 11 to 12 years, they should be targeted in education efforts. Finally, physicians who believed that parents are less likely to accept the HPV vaccine if discussed in the context of other adolescent vaccines were less likely to discuss it at the 11- to 12-year-old visit. In contrast, qualitative studies of health care providers’ approaches to HPV vaccination have found that those who recommend all adolescent vaccines together believe this approach leads to higher uptake.15,24

Our study has some limitations. Although we have previously shown that the surveyed physicians are generally representative of physicians in the AAP and AAFP with respect to demographic and practice characteristics and locations throughout the United States, those who agreed to be surveyed might have different attitudes and practices than those who chose not to be in the network and those who did not respond to the survey.10 Physicians’ practices were self-reported and not directly observed, and we did not specifically define what behaviors constituted discussion of HPV vaccine or a “strong recommendation.”

CONCLUSIONS

Many physicians report experiencing parental deferral of HPV vaccine for their 11- to 12-year-old patients, and this expectation of deferral may cause them to avoid discussing the HPV vaccine. Ongoing public health efforts may promote positive parental attitudes about the HPV vaccine and reduce physicians’ experience with parental deferral. Because some physicians could be overestimating the likelihood of parental deferral, they should be encouraged to rethink their assumptions about parental attitudes regarding the HPV vaccine and strongly recommend it at every 11- to 12-year-old well-child visit. Our results indicate that physicians themselves may need a clearer understanding of the reasons to vaccinate against HPV at 11 to 12 years old versus later in adolescence and the reasons to vaccinate boys. In addition, physicians may need guidance on discussing these reasons with parents. Future research could investigate whether public health efforts directed at parents, education of physicians by professional organizations, and tools from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and professional organizations will increase physicians’ discussion of the HPV vaccine and strength of recommendation for 11- to 12-year- old girls and boys.30

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT:

TheHPV vaccine could prevent thousands of cancers in the United States each year; however, HPV vaccine coverage is lower than for other adolescent vaccines and lower for boys. HPV vaccination is recommended for all 11- to 12-year-olds, but missed opportunities are common.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS:

Eighteen percent of physicians are not discussing the HPV vaccine at the 11- to 12-year-old well-child visit, likely contributing to missed opportunities. Physicians’ likelihood of initiating a conversation is diminished by an expectation that parents are likely to defer the vaccine.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Lynn Olson, PhD, and Karen O’Connor from the Department of Research, AAP, Bellinda Schoof, MHA, at the AAFP, and the leaders of the AAP and AAFP for collaborating in the establishment of the sentinel networks in pediatrics and family medicine. They also thank all pediatricians and FP in the networks for participating and responding to this survey.

FUNDING: Funded by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention SIP (5U48DP0011938) through the Rocky Mountain Prevention Research Center Funded by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention PEP (MM-1040–08/08) through the Association of American Medical Colleges, Washington, District of Columbia.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

- AAFP

American Academy of Family Physicians

- aOR

adjusted odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- FP

family medicine physicians

- HPV

human papillomavirus

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors, and they do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV-associated cancers statistics. HPV and cancer. Available at: www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.htm. Accessed June 30, 2015

- 2.Satterwhite CL, Torrone E, Meites E, et al. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2008. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(3):187–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillison ML, Alemany L, Snijders PJ, et al. Human papillomavirus and diseases of the upper airway: head and neck cancer and respiratory papillomatosis. Vaccine. 2012;30(suppl 5):F34–F54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(32):4294–4301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Human papillomavirus-associated cancers— United States, 2004–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:258–261 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Human papillomavirus vaccination: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63(RR-05):1–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reagan-Steiner S, Yankey D, Jeyarajah J, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(29):784–792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stokley S, Jeyarajah J, Yankey D, et al. ; Immunization Services Division, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage among adolescents, 2007–2013, and postlicensure vaccine safety monitoring, 2006–2014—United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(29):620–624 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holman DM, Benard V, Roland KB, Watson M, Liddon N, Stokley S. Barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among US adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(1):76–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crane LA, Daley MF, Barrow J, et al. Sentinel physician networks as a technique for rapid immunization policy surveys. Eval Health Prof. 2008;31(1):43–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Babbie ER. The Practice of Social Research. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company; 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 12.McMahon SR, Iwamoto M, Massoudi MS, et al. Comparison of e-mail, fax, and postal surveys of pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2003;111(4 pt 1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/111/4pt1/e299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dorell C, Yankey D, Jeyarajah J, et al. Delay and refusal of human papillomavirus vaccine for girls, national immunization survey- teen, 2010. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2014;53(3):261–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Healy CM, Montesinos DP, Middleman AB. Parent and provider perspectives on immunization: are providers overestimating parental concerns? Vaccine. 2014;32(5):579–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughes CC, Jones AL, Feemster KA, Fiks AG. HPV vaccine decision making in pediatric primary care: a semi- structured interview study. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11(1):74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McRee AL, Gilkey MB, Dempsey AF HPV vaccine hesitancy: findings from a statewide survey of health care providers. J Pediatr Health Care. 2014;28(6):541–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gargano LM, Herbert NL, Painter JE, et al. Impact of a physician recommendation and parental immunization attitudes on receipt or intention to receive adolescent vaccines. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(12):2627–2633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lau M, Lin H, Flores G. Factors associated with human papillomavirus vaccine-series initiation and healthcare provider recommendation in US adolescent females: 2007 National Survey of Children’s Health. Vaccine. 2012;30(20):3112–3118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahman M, Laz TH, McGrath CJ, Berenson AB. Provider recommendation mediates the relationship between parental human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine awareness and HPV vaccine initiation and completion among 13- to 17- year-old US adolescent children. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2015;54(4): 371–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fiks AG, Grundmeier RW, Mayne S, et al. Effectiveness of decision support for families, clinicians, or both on HPV vaccine receipt. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):1114–1124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gowda C, Schaffer SE, Dombkowski KJ, Dempsey AF Understanding attitudes toward adolescent vaccination and the decision-making dynamic among adolescents, parents and providers. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayne SL, duRivage NE, Feemster KA, Localio AR, Grundmeier RW, Fiks AG. Effect of decision support on missed opportunities for human papillomavirus vaccination. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(6):734–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perkins RB, Clark JA, Apte G, et al. Missed opportunities for HPV vaccination in adolescent girls: a qualitative study. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/134/3/e666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perkins RB, Zisblatt L, Legler A, Trucks E, Hanchate A, Gorin SS. Effectiveness of a provider-focused intervention to improve HPV vaccination rates in boys and girls. Vaccine. 2015;33(9):1223–1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rand CM, Shone LP, Albertin C, Auinger P, Klein JD, Szilagyi PG. National health care visit patterns of adolescents: implications for delivery of new adolescent vaccines. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(3):252–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsai Y, Zhou F, Wortley P, Shefer A, Stokley S. Trends and characteristics of preventive care visits among commercially insured adolescents, 2003–2010. J Pediatr. 2014;164(3):625–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss MJ, Spitznagel EL, et al. Age of sexual debut among US adolescents. Contraception. 2009;80(2):158–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohn AC, MacNeil JR, Clark TA, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention and control of meningococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62(RR-2):1–28 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Vincenzo R, Conte C, Ricci C, Scambia G, Capelli G. Long-term efficacy and safety of human papillomavirus vaccination. Int J Womens Health. 2014;6: 999–1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV Vaccine Resources for Healthcare Professionals: Preteen and Teen Vaccines. 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/index.html. Accessed December 10, 2015